A tattoo is a form of body modification where a design is made by inserting ink, dyes and pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to change the pigment. The art of making tattoos is tattooing. Tattoos fall into three broad categories: purely decorative (with no specific meaning); symbolic (with a specific meaning pertinent to the wearer); and pictorial (a depiction of a specific person or item). In addition, tattoos can be used for identification such as ear tattoos on livestock as a form of branding.

Tattooing is one of the oldest art forms on the planet, dating to prehistoric times and cave dwellers who often created tattoos as part of ritual practices linked to shamanism, protection, connection with their gods, and embueing them with magical powers. Early tattooing was used to symbolize the fertility of the earth and of womankind, preservation of life after death, the sacredness of chieftainship and other cultural factors.

Tattooed markings on skin and incised markings in clay provide some of the earliest evidence that humans have long practiced a wide range of body art. The written accounts of early European explorers also attest to the elaborate and widespread nature of tattooing in various parts of the world, providing an insight into traditions that had their origins deep in the past.

Marriage tattoos have been particularly popular to insure that you can find your lawful spouse or spouses in the afterlife, even if you have passed 'through the veil,' many years apart. Ancient Ainu marriage rites state that a woman who marries without first being tattooed, in the proper manner, commits a great sin and when she dies; she will go straight to God.

Tattooing as a rite of adulthood, or passage into puberty, was another common tattoo ritual. If a girl can't take the pain of tattooing, she is un-marriageable, because she will never be able to deal with the pain of child birth. If a boy cannot deal with the pain of his puberty tattoos, he is considered to be a bad risk as a warrior, and could become an outcast.

Since the dawn of tattooing, people have been marking themselves with the signs of their totem animals. On the outer level of meaning, they are trying to gain the strengths and abilities of the totem animal. On a more inner and mystical level, totem animals mean that the bearer has a close and mysterious relationship with this animal spirit as his guardian. Totem animal tattoos often double as clan or group markings. Modern dragon, tiger, and eagle tattoos often subconsciously fall into this category. My snake tattoos are examples of DNA and the human biogenetic experiment.

Another common practice was tattooing for health wherein the tattooing of a god was placed on the afflicted person, to fight the illness for them. An offshoot of tattooing for health is tattooing to preserve youth. Maori girls tattooed their lips and chin, for this reason. When an old Ainu lady's eyesight is failing, she can re-tattoo her mouth and hands, for better vision. This is still practiced today.

Tattoos for general good luck are found world-wide. A man in Burma who desires good luck will tattoo a parrot on his shoulder. In Thailand, a scroll representing Buddha in an attitude of meditation is considered a charm for good luck. In this charm, a right handed scroll is masculine and a left handed scroll is feminine. Today, in the West, you can see dice, spades, and Lady Luck tattoos, which are worn to bring luck. Read more

Sacred Armor composed of dot work, Tibetan Black Work,

Various mandalas with a little baroque added in.

Tattooing has been a Eurasian practice since Neolithic times. "Otzi the Iceman", dated circa 3300 BC, exhibits possible therapeutic tattoos (small parallel dashes along lumbar and on the legs).

Artist Tattooed Himself to Solve Mystery of Otzi The Iceman's Tattoos

Science Alert - March 14, 2024

Otizi died around 5,300 years ago was tattooed using methods fascinatingly similar to modern ones. Otzi the Iceman, whose exceptionally mummified remains were found decades ago in a glacier in the Otztal Alps, was covered in tattoos. Scientists carefully studying his remains have counted 61 carbon pigment markings on his lower back, abdomen, left wrist, and lower legs. Most of the archaeologists who have discussed Otzi's tattoos in recent years are upfront that we don't know how they were made - but the idea still appears in just about every popular media discussion.

China: Tarim Basin (West China, Xinjiang) revealed several tattooed mummies of a Western (Western Asian/European) physical type. Still relatively unknown - the Tarim Mummies could date from the end of the 2nd millennium BCE.

The world's most spectacular tattooed mummy was discovered by Russian anthropologist Sergei Ivanovich Rudenko in 1948 during the excavation of a group of Pazyryk tombs about 120 miles north of the border between China and Russia.

These mummies were found in the High Altai Mountains of western and southern Siberia and date from around 2400 years ago. The tattoos on their bodies represent a variety of animals. The griffins and monsters are thought to have a magical significance but some elements are believed to be purely decorative. Altogether the tattoos are believed to reflect the status of the individual.

Three tattooed mummies (c. 300 BCE) were extracted from the permafrost of Altai in the second half of the 20th century (the Man of Payzyrk, during the 1940s; one female mummy and one male in Ukok plateau, during the 1990s). Their tattooing involved animal designs carried out in a curvilinear style.

The Man of Pazyryk was also tattooed with dots that lined up along

the spinal column (lumbar region) and around the right ankle.

The Pazyryks were formidable iron age horsemen and warriors who inhabited the steppes of Eastern Europe and Western Asia from the sixth through the second centuries BC. They left no written records, but Pazyryk artifacts are distinguished by a sophisticated level of artistry and craftsmanship. The Pazyryk tombs discovered by Rudenko were in an almost perfect state of preservation. They contained skeletons and intact bodies of horses and embalmed humans, together with a wealth of artifacts including saddles, riding gear, a carriage, rugs, clothing, jewelry, musical instruments, amulets, tools, and, interestingly, hash pipes, described by Rudenko as "apparatus for inhaling hemp smoke".

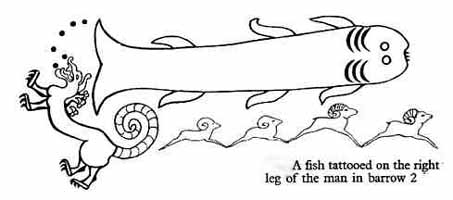

Also found in the tombs were fabrics from Persia and China, which the Pazyryks must have obtained on journeys covering thousands of miles. Rudenko's most remarkable discovery was the body of a tattooed Pazyryk chief: a thick-set, powerfully built man who had died when he was about 50. Parts of the body had deteriorated, but much of the tattooing was still clearly visible. The chief was elaborately decorated with an interlocking series of designs representing a variety of fantastic beasts.

The best preserved tattoos were images of a donkey, a mountain ram, two highly stylized deer with long antlers and an imaginary carnivore on the right arm. Two monsters resembling griffins decorate the chest, and on the left arm are three partially obliterated images which seem to represent two deer and a mountain goat.

On the front of the right leg a fish extends from the foot to the knee. A monster crawls over the right foot, and on the inside of the shin is a series of four running rams which touch each other to form a single design. The left leg also bears tattoos, but these designs could not be clearly distinguished. In addition, the chief's back is tattooed with a series of small circles in line with the vertebral column. This tattooing was probably done for therapeutic reasons. Contemporary Siberian tribesmen still practice tattooing of this kind to relieve back pain.

No instruments specifically designed for tattooing were found, but the Pazyryks had extremely fine needles with which they did miniature embroidery, and these were undoubtedly used for tattooing In the summer of 1993 another tattooed Pazyryk mummy was discovered in Siberia's Umok plateau. It had been buried over 2,400 years ago in a casket fashioned from the hollowed-out trunk of a larch tree. On the outside of the casket were stylized images of deer and snow leopards carved in leather. Shortly after burial the grave had apparently been flooded by freezing rain and the entire contents of the burial chamber had remained frozen in permafrost.

The body was that of a young woman whose arms had been tattooed with designs representing mythical creatures like those on the previously discovered Pazyryk mummy. She was clad in a voluminous white silk dress, a long crimson woolen skirt and white felt stockings.

On her head was an elaborate headdress made of hair and felt - the first of its kind ever found intact. Also discovered in the burial chamber were gilded ornaments, dishes, a brush, a pot containing marijuana, and a hand mirror of polished metal on the wooden back of which was a carving of a deer. Six horses wearing elaborate harnesses had been sacrificed and lay on the logs which formed the roof of the burial chamber.

Considering the number of tattooed mummies which have been discovered, it is apparent that tattooing was widely practiced throughout the ancient world and was associated with a high level of artistic endeavor. The imagery of ancient tattooing is in many ways similar to that of modern tattooing.

All of the known Pazyryk tattoos are images of animals. Animals are the most frequent subject matter of tattooing in many cultures and are traditionally associated with magic, totemism, and the desire of the tattooed person to become identified with the spirit of the animal. Tattoos which have survived on mummies suggest that tattooing in prehistoric times had much in common with modern tattooing, and that tattooing the world over has profound and universal psychic origins.

Tattooing for spiritual and decorative purposes in Japan is thought to extend back to at least the Jomon or paleolithic period (approximately 10,000 BCE) and was widespread during various periods for both the Japanese and the native Ainu. Chinese visitors observed and remarked on the tattoos in Japan (300 BCE).

In Japanese the word used for traditional designs or those that are applied using traditional methods is irezumi ("insertion of ink"), while "tattoo" is used for non-Japanese designs. The earliest evidence of tattooing in Japan comes from figurines called dogu. Most of these date to 3000 years ago and display similar markings to the tattooed mouths found among the women of the Ainu (the Indigenous people of Japan).

Tattoo enthusiasts may refer to tattoos as tats, ink, art or work, and to tattooists as artists. The latter usage is gaining support, with mainstream art galleries holding exhibitions of tattoo designs and photographs of tattoos. Tattoo designs that are mass-produced and sold to tattoo artists and studios and displayed in shop are known as flash. Irezumi

Tattooing has also been featured prominently in one of the Four Classic Novels in Chinese literature, Water Margin, in which at least three of the 108 characters, Lu Zhi Chen, Shi Jin, and Yan Chen are described as having tattoos covering nearly the whole of their bodies. In addition, Chinese legend has it that the mother of Yue Fei, the most famous general of the Song Dynasty, tattooed the words jin zhong bao guo on his back with her sewing needle before he left to join the army, reminding him to "repay his country with pure loyalty". China

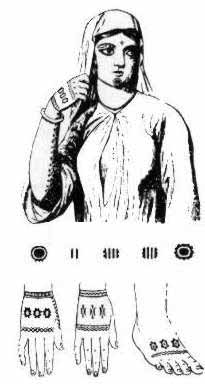

Tattooing has actually been practiced since the time of the ancient Egyptians and is common throughout the world. In 1891, archaeologists discovered the mummified remains of Amunet - Dynasty XI, Egypt, c. 4040 - 3994 years ago. This mummy was found at Thebes. Amunet (various spellings) was a priestess of Hathor. This female mummy displayed several lines and dots and dashes tattooed on her body, aligned in abstract geometrical patterns.

These dot-and-dash patterns have been seen for many years throughout Egypt. This pattern and skill of tattoo may have been borrowed from the Nubians. The art of tattoo developed during the Middle Kingdom and flourished beyond. The evidence to date suggests that this art form was restricted to women only, and usually these women were associated with ritualistic practice. These mummies give us site into how long this art form has been practiced and how their art was displayed. From continent to continent this art form has developed and transformed. Through the Egyptian eyes to other cultures, tattoo is something that satisfies various needs and interest.

A second mummy also found depicted this same type of line pattern (the dancer). This mummy also had a cicatrix pattern over her lower pubic region. In the figure to the right you can see the various patterns as they are displayed on the body. The various design patterns also appeared on several figurines that date to the Middle Kingdom, these figurines have been labeled the "Brides of Death." The figurines are also associates with the goddess Hathor. All tattooed Egyptian mummies found to date are female. The location of the tattoos on the lower abdomen are thought to be linked to fertility.

Egyptian tattooing was someitmes related to the sensual, erotic, and emotional side of life, and all these themes are found in tattooing today.

An archaic practice in the Middle East involved people cutting themselves and rubbing in ash during a period of mourning after an individual had died. It was a sign of respect for the dead and a symbol of reverence and a sense of the profound loss for the newly departed; and it is surmised that the ash that was rubbed into the self-inflicted wounds came from the actual funeral pyres that were used to cremate bodies. In essence, people were literally carrying with them a reminder of the recently deceased in the form of tattoos created by ash being rubbed into shallow wounds cut or slashed into the body, usually the forearms.

Body art was all the rage in early Australia, as it was in many other parts of the ancient world, and now a new study reports that elaborate and distinctive designs on the skin of indigenous Aussies repeated characters and motifs found on rock art and all sorts of portable objects, ranging from toys to pipes. The study not only illustrates the link between body art, such as tattoos and intentional scarring, with cultural identity, but it also suggests that study of this imagery may help to unravel mysteries about where certain groups traveled in the past, what their values and rituals were, and how they related to other cultures.

"Distinctive design conventions can be considered markers of social interaction so, in a way (they are) a cultural signature of sorts that archaeologists can use to understand ways people were interacting in the past," author Liam Brady of Monash University's Center for Australian Indigenous Studies, told Discovery News.

For the study, published in the latest issue of the journal Antiquity, Brady documented rock art drawings; images found on early turtle shell, stone and wood objects, such as bamboo tobacco pipes and drums; and images that were etched onto the human body through a process called scarification. "In a way, a scarred design could be interpreted as a tattoo," Brady said. "It was definitely a distinctive form of body ornamentation and it was permanent since the design was cut into the skin. Evidence for scarification is primarily via (19th century) anthropologists - mainly A.C. Haddon -- who took black and white photographs of some designs, as well as drawing others into his notebooks in the late 1800's," he added.

Both Haddon and Brady focused their attention on a region called the Torres Strait. This is a collection of islands in tropical far northeastern Queensland. The islands lie between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. Although people were living in the Torres Strait as early as 9,000 years ago, when sea levels were lower and a land bridge connected Australia with New Guinea, archaeological exploration of the area only really began with Haddon's 19th century work. Since body art, rock art, wooden objects and other tangible items have a relatively short shelf life, Haddon's collections and data represent some of the earliest confirmed findings for the region.

Brady determined that within the body art, rock art and objects, four primary motifs often repeated: a fish headdress, a snake, a four-pointed star, and triangle variants. The fish headdress, usually made of a turtle shell decorated with feathers and rattles, was worn during ceremonies and has, in at least one instance, been linked to a "cult of the dead." The triangular designs, on the other hand, were often scarred onto women's skin and likely indicated these individuals were in mourning. Analysis of the materials found that two basic groups -- horticulturalists and hunter-gatherers -- inhabited the Torres Strait during its early history. Aboriginal people at Cape York, a peninsula close to Australia, had "a different artistic system in operation, which did not incorporate many designs from Papua New Guinea," Brady said.

Based on land locations where the body art and object imagery were found, as well as the nature of the designs, Brady concludes that the Cape York residents were the hunter-gatherers, while groups in more northerly locations within Torres Strait appear to have been horticulturalists. Since imagery mixed and matched more among the early farmers, Brady concludes they enjoyed kinship links, and engaged in extensive trade, with Papua New Guinea groups. In the future, similar studies could help to identify cultural groups in other regions, while also revealing their social interactions. Such studies could prove particularly useful for other parts of Australia and New Zealand, where tattooing and body art, as well as totems -- protection entities often depicted with colorful imagery -- were common.

Recently, for example, the Field Museum in Chicago returned the human remains of 14 Maori native New Zealanders back to their country of origin. The remains are now at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa. Included in the collection of mandibles, crania and other bones is "one preserved head with facial tattoos," according to a Field Museum announcement. In an act of repatriation, nine tattooed Maori heads were also recently gifted to Te Papa by Scotland's Aberdeen Museum. Te Taru White, a Maori specialist at Te Papa, said the "ancestors" made "the long journey home to New Zealand and to their people." The heads are now in a consecrated, sacred space within the New Zealand museum, where they may be studied and researched further. In Brady's case, his work was undertaken as part of collaborative research projects initiated by certain Torres Strait and Aboriginal communities.

The term "tattoo" is traced to the Tahitian tatu or tatau, meaning to mark or strike, the latter referring to traditional methods of applying the designs.

The earliest evidence of tattooing in the Pacific is in the form of this pottery shard which is approximately 3000 years old. The Lapita face shows dentate (pricked) markings on the nose, cheeks and forehead, suggestive of the technique of tattoo application.

Maori of New Zealand

Between 1766 and 1779, Captain James Cook made three voyages to the South Pacific, the last trip ending with Cook's death in Hawaii in February, 1779. When Cook and his men returned home to Europe from their voyages to Polynesia, they told tales of the 'tattooed savages' they had seen.

Cook's Science Officer and Expedition Botanist, Sir Joseph Banks, returned to England with a tattoo. Banks was a highly regarded member of the English aristocracy and had acquired his position with Cook by putting up what was at the time the princely sum of some ten thousand pounds in the expedition. In turn, Cook brought back with him a tattooed Tahitian chief, whom he presented to King George and the English Court. Many of Cook's men, ordinary seamen and sailors, came back with tattoos, a tradition that would soon become associated with men of the sea in the public's mind and the press of the day. In the process sailors and seamen re-introduced the practice of tattooing in Europe and it spread rapidly to seaports around the globe.

It was in Tahiti aboard the Endeavor, in July of 1769, that Cook first noted his observations about the indigenous body modification and is the first recorded use of the word tattoo. In the Ship's Log, Cook recorded this entry: "Both sexes paint their bodies, "Tattow," as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the color of black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible. This method of Tattowing is a painful operation, especially the Tattowing of their buttocks. It is performed but once in their lifetimes.

The British Royal Court must have been fascinated with the Tahitian chief's tattoos, because the future King George V had himself inked with the 'Cross of Jerusalem' when he traveled to the Middle East in 1892. He also received a dragon on the forearm from the needles of an acclaimed tattoo master during a visit to Japan. George's sons, The Duke of Clarence and The Duke of York were also tattooed in Japan while serving in the British Admiralty, solidifying what would become a family tradition.

Taking their sartorial lead from the British Court, where Edward VII followed George V's lead in getting tattooed; King Frederick IX of Denmark, the King of Romania, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King Alexander of Yugoslavia and even Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, all sported tattoos, many of them elaborate and ornate renditions of the Royal Coat of Arms or the Royal Family Crest. King Alfonso of modern Spain also had a tattoo.

Tattooing spread among the upper classes all over Europe in the nineteenth century, but particularly in Britain where it was estimated in Harmsworth Magazine in 1898 that as many as one in five members of the gentry were tattooed. There, it was not uncommon for members of the social elite to gather in the drawing rooms and libraries of the great country estate homes after dinner and partially disrobe in order to show off their tattoos. Aside from her consort Prince Albert, there are persistent rumours that Queen Victoria had a small tattoo in an undisclosed 'intimate' location; Denmark's king Frederick was filmed showing his tattoos taken as a young sailor. Winston Churchill's mother, Lady Randolph Churchill, not only had a tattoo of a snake around her wrist, which she covered when the need arose with a specially crafted diamond bracelet, but had her nipples pierced as well. Carrying on the family tradition, Winston Churchill was himself tattooed. In most western countries tattooing remains a subculture identifier, and is usually performed on less-often exposed parts of the body.

Pre-Christian Germanic Celtic and other central and northern European tribes were often heavily tattooed, according to surviving accounts. The pictures were famously tattooed (or scarified) with elaborate dark blue woad (or possibly copper for the blue tone) designs. Julius Caesar described these tattoos in Book V of his Gallic Wars (54 BCE).

Ahmad ibn Fadlan also wrote of his encounter with the Scandinavian Rus' tribe in the early 10th century, describing them as tattooed from "fingernails to neck" with dark blue "tree patterns" and other "figures."

During the gradual process of Christianization in Europe, tattoos were often considered remaining elements of paganism and generally legally prohibited. According to Robert Graves in his book The Greek Myths tattooing was common amongst certain religious groups in the ancient Mediterranean world, which may have contributed to the prohibition of tattooing in Leviticus.

The Greeks learned tattooing from the Persians. Tattooing is mentioned in accounts by Plato, Aristophanes, Julius Caesar and Herodotus. Tattoos were generally used to mark slaves and punish criminals.

The Romans adopted tattooing from the Greeks. In the 4th century, the first Christian emperor of Rome banned the facial tattooing of slaves and prisoners. In 787, Pope Hadrian prohibited all forms of tattooing.

In the 18th century, many French sailors returning from voyages in the South Pacific had been elaborately tattooed. In 1861, French naval surgeon, Maurice Berchon, published a study on the medical complications of tattooing. After this, the Navy and Army banned tattooing within their ranks.

The ancient Celts didn't have much in the way of written record keeping, consequently, there is little evidence of their tattooing remaining. Most modern Celtic designs are taken from the Irish Illuminated Manuscripts, of the 6th and 7th centuries. This is a much later time period than the height of Celtic tattooing. Designs from ancient stone and metal work are more likely to be from the same time period as Celtic tattooing.

In England, tattooing flourished in the 19th century and became something of a tradition in the British Navy. In 1862, the Prince of Wales received his first tattoo - a Jerusalem cross - after visiting the Holy Land. In 1882, his sons, the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of York (later King George V) were tattooed by the Japanese master tattooist, Hori Chiyo.

In Peru, tattooed Inca mummies dating to the 11th century have been found. Inca tattooing is characterized by bold abstract patterns which resemble contemporary tribal tattoo designs.

In Mexico and Central America, 16th century Spanish accounts of Mayan tattooing reveal tattoos to be a sign of courage. When Cortez and his conquistadors arrived on the coast of Mexico in 1519 they were horrified to discover that the natives not only worshipped devils in the form of statues and idols, but had somehow managed to imprint indelible images of these idols on their skin. The Spaniards, who had never heard of tattooing, recognized it at once as the work of Satan. As far as we know, only one Spaniard was ever tattooed by the Mayas. His name was Gonzalo Guerrero, and he is mentioned in several early histories of Mexico.

In North America, early Jesuit accounts testify to the widespread practice of tattooing among Native Americans. Among the Chickasaw, outstanding warriors were recognized by their tattoos. Among the Ontario Iroquoians, elaborate tattoos reflected high status.

When Europeans first arived in the New World, they found Native Americans had a rich and ancient tattooing tradition. Capt. John Smith, of Virginia, mentioned Native American tattoos in his writing in the 1600's. Most tribes celebrated adulthood with tattoo puberty rites. Simple lines and geometric patterns were used and women often had lines extending from the lower lip onto the chin. Arapaho men tattooed three dots on their own chest, to prove their manhood. The Sioux, among other tribes, believed that tattoos were necessary as a rite de passage into the spirit world. As a ghost warrior rode towards the "Many Lodges", he would encounter an old woman, who would demand to see his tattoos. If he had none to show, he and his horse were pushed off the path, and fell to earth, where they became aimlessly wandering spirits, who were eternally not satisfied. With the coming of Christianity, Native American tattooing disappeared and stories changed, until we only hear of the body painting of the American Indians.

In north-west America, Inuit women's chins were tattooed to indicate marital status and group identity.

Tattooing is probably the most popular form of body adornment in America today. The designs can be small and discreet or large and obvious. Many people prefer discreet designs that can be concealed for certain occasions.

2,300-year-old arm tats on mummified woman reveal new insights about tattooing technique in ancient Siberia Live Science - August 1, 2025

Fantastical animal imagery on the forearms of a 2,300-year-old mummified woman is revealing new information about the art of tattooing in ancient Siberia. Thanks to cutting-edge photography, archaeologists have discovered that a virtuoso artist used a previously unknown tattoo tool to "hand-poke" the designs in multiple stages.

World's oldest complete tattooing kit dating back 2,700 years found in Tonga contains tools made from human bones Daily Mail - March 5, 2019

The world's oldest-known tattoo kit has been discovered and it includes tools made from human bones, scientists have confirmed. Multi-pronged tattoo combs that look similar to some modern tattoo artists' tools were found in Tonga, in the Southern Pacific Ocean. The kit dates back 2,700 years and pushes the dawn of human tattooing to the start of the Polynesian culture.

World's first tattoo parlor dating back 2,000 years equipped with tools made from cactus spines is discovered in Utah Daily Mail - February 28, 2019

One of the earliest tools for tattooing human skin has been discovered in America and it dates back 2,000 years. The primitive instrument is made of a skunk bush wooden handle and penetrating cactus-spines that were used to embed pigment under the skin. It was discovered and placed in storage more than 40 years ago but its true purpose has only just been discovered.

How Tattoo Ink and Gold Could (One Day) Help Restore Vision Live Science - May 7, 2018

An artificial retina made of organic ink and gold may be able to restore vision someday, a new study suggests. The new device is an extremely thin sheet of organic crystal pigments, which are widely used in printing ink, cosmetics and tattoos. When these pigments are arranged in a particular layered geometry, the crystals can absorb light and convert it to electric signals, just like the light-sensitive cells - called photoreceptors - in the eye's retina and make vision possible, according to the study,

Pigments and bones found in a 3,600-year-old native American burial site are found to be the world's oldest Tattoo kit Daily Mail - May 7, 2018

At first glance, it looks like nothing but a pile of old bones - but these relics actually comprise the oldest tattoo kit in the world. The artifacts were buried in a native American grave west of Nashville, Tennessee, at least 3,600 years ago and remained entombed there until 1985. Since then the set of turkey bones, pigment-filled half-shells, and stone tools have sat in storage; their true significance unnoticed.

History of tattooing is rewritten after world's earliest figurative inkings are found on 5,000-year-old Egyptian mummies in the British Museum Daily Mail - March 1, 2018

The world's earliest figurative tattoos have been discovered on 5,000-year-old Egyptian mummies at the British Museum, rewriting the history of inking. The tattoos are of a wild bull and a Barbary sheep on the upper-arm of a male mummy, and S-shaped motifs on the upper-arm and shoulder of a female. The find dates tattoos containing imagery rather than geometric patterns to 1,000 years earlier than previously thought. Researchers say the discovery 'transforms' our understanding of how people lived during this period.

Prehistoric Tattoos Were Made with Volcanic Glass Tools Live Science - July 6, 2016

Volcanic glass tools that are at least 3,000 years old were used for tattooing in the South Pacific in ancient times, a new study finds. The skin-piercing tools could yield insight into ancient tattooing practices in the absence of tattooed human remains. Research conducted over the past 25 years found 5,000-year-old tattoos on a mummy in the Alps. However, such exceptionally preserved human remains are rare, which makes it difficult to use them to learn more about the ancient history of tattooing.

Egyptian Mummy's Symbolic Tattoos Are 1st of Their Kind Live Science - May 10, 2016

More than 3,000 years ago, an ancient Egyptian woman tattooed her body with dozens of symbols - including lotus blossoms, cows and divine eyes - that may have been linked to her religious status or her ritual practice. Preserved in amazing detail on her mummified torso, the surviving images represent the only known examples of tattoos found on Egyptian mummies showing recognizable pictures, rather than abstract designs. The mummy was found at a site on the west bank of the Nile River known as Deir el-Medina, a village dating to between 1550 B.C. and 1080 B.C. that housed artisans and workers who built the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings

Global Semicolon Tattoo Trend Is A Sign Of Strength Among Faithful Individuals Dealing With Mental Health Problems Huffington Post - July 16, 2015

The trend of semicolon tattoos was started by Project Semicolon, which describes itself as "a faith-based non-profit movement dedicated to presenting hope and love to those who are struggling with depression, suicide, addiction and self-injury." As to the significance of the symbol itself, the organization writes on its website, "a semicolon is used when an author could've chosen to end their sentence, but chose not to. The author is you and the sentence is your life;" thus, in the case of these tattoos, it is a physical representation of personal strength in the face of internal struggle.