-

-

In Sumerian and Akkadian (Babylonian and Assyrian) mythology, Ereshkigal, wife of Nergal, was the goddess of Irkalla, the land of the dead. She managed the destiny of those who were beyond the grave, in the Underworld, where she was queen.

It was said that she had been stolen away by Kur and taken to the Underworld, where she was made queen unwillingly. She is actually the twin sister of Enki. Ereshkigal was the only one who could pass judgement and give laws in her kingdom, and her name means "Lady of the Great Place", "Lady of the Great Earth", or "Lady of the Great Below". Her main temples were at Kutha and Sippar.

Ereshkigal was also Inanna and Ishtar (see below).

The Me is creation out of chaos, the great attributes of civilization, and the powers of the gods. The me were conferred by the gods on other gods or on the king-priests, who as the representatives of the gods on Earth, ensured the continuation of civilization. The special powers, contained within the me allowed the holy plan or design to be implemented on Earth. The me were contained within special objects of great sacred value, such as the royal throne, the sacred bed, the temple drum, the scepter, the crown, and other special articles of clothing or jewelry to be worn, sat on, lied in, and so forth. Enki gave Eanna the the Me which empowered her becoming Goddess and Queen of Heaven and Earth, now able to descend into the Underworld and ascend once again.

-

-

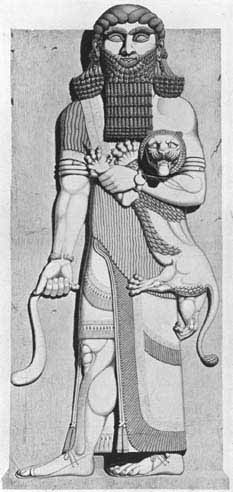

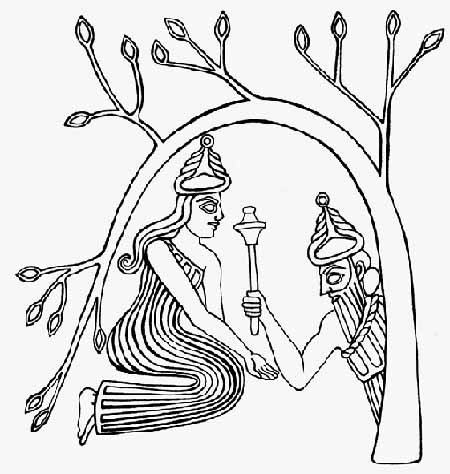

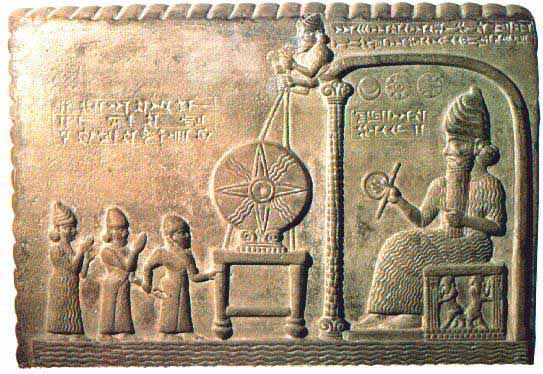

On either side of her cult statue shown above is the ring-post, also known as Inanna's knot- in Egypt the Atef Crown. This was a sacred symbol of Inanna, associated with her. It represents a door-post made from a bundle of reeds, the upper ends, bent into a loop to hold a cross-pole. The ring-post is shown on many depictions of Inanna, including those of the famed Warka Vase.

Gilgamesh

The goddess Inanna was the patron and special god/goddess of the ancient Sumerian city of Erech (Uruk), the City of Gilgamesh. As Queen of heaven, she was associated with the Evening Star (the planet Venus), and sometimes with the Moon. She may also have been associated the brightest stars in the heavens, as she is sometimes symbolized by an eight-pointed star, a seven-pointed star, or a four pointed star. In the earliest traditions, Inanna was the daughter of An, the Sky, Ki, the Earth (both of Uruk and Warka). In later Sumerian traditions, she is the daughter of Nanna (Narrar), the Moon God and Ningal, the Moon Goddess (both of Ur).

Inanna could be wily and cunning. She was a powerful warrior, who drove a war chariot, drawn by lions. In the duality of our reality she is portrayed as gentle and loving, a source of beauty and grace, a source of inspiration. She endowed the people of Sumer with gifts that inspired and insured their growth as a people and a culture. She is also depicted as a passionate, sensuous lover in The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi (see below), which established the principle of Sacred Marriage. Indeed, one aspect of Inanna is as the Goddess of Love, and it is in this aspect that she embodies creativity, procreativity, passion, raw sexual energy and power.

During the time the Goddess Inanna ruled the people of Sumer, they and their communities prospered and thrived. The urban culture, though agriculturally dependent, centered upon the reverence of the Goddess - a cella, or shrine, in her honor was the centerpiece of the cities. Inanna was the queen of seven temples throughout Sumer.

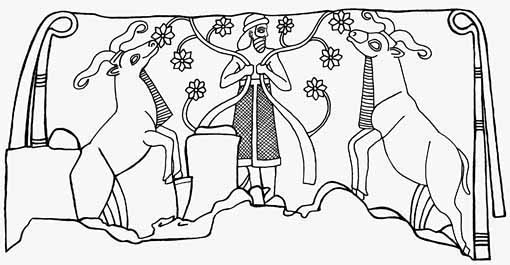

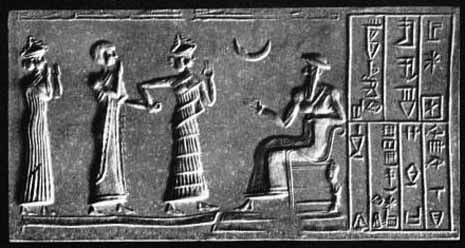

Mesopotamian cylinder seal. Hematite. 2000-1600 BCE.

Inanna was said to descend from the ancient family of the creator goddess Nammu, who was her grandmother. Inanna held "full power of judgment and decision and the control of the law of heaven and earth." Her sacred planet was Venus, the evening star. She was often symbolized as a lioness in battle. Along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers were many shrines and temples dedicated to her.

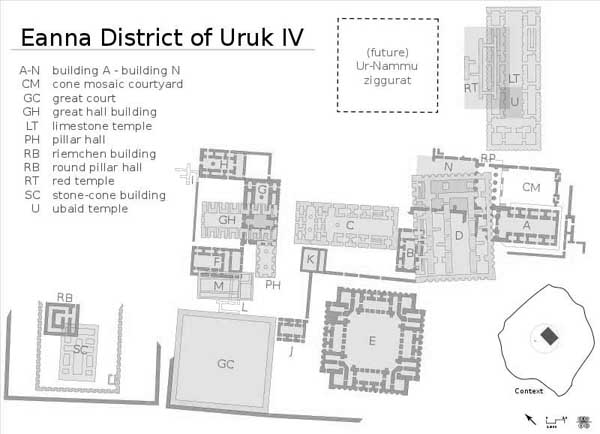

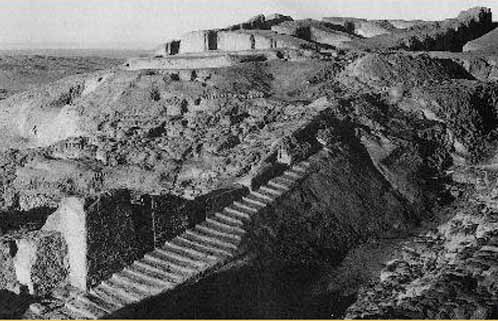

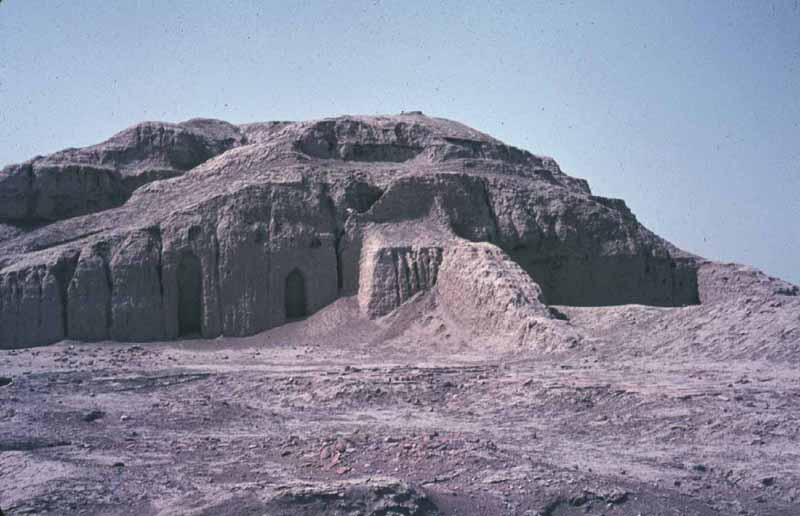

Remains of the Eanna Temple and Ziggurat at Uruk

The temple of EAnna, Inanna's House of Heaven, in Uruk, was the greatest of these. This temple was 5000 years old and had been built and rebuilt many times to hold a community of sacred women who cared for the temple lands. The high priestess of Inanna would choose for her bed one she would appoint as shepherd. He would represent Dumuzi, her sacred lover.

Eanna and Dumuzi create the Tree of Life

Mesopotamian cylinder seal. Marble. About 3200-3000 BCE.

Dumuzi in net skirt (symbolizes grids) feeding sheep.

Inanna's standards ("gateposts") that frame the image suggest

that the event is happening inside her temple grounds.

�Dumuzid or Dumuzi, called "the Shepherd", from Bad-tibira in Sumer, was, according to the Sumerian King List, the fifth predynastic king in the legendary period before the Deluge. The list further states that Dumuzid ruled for 36,000 years.

"Dumuzid the Shepherd" is also the subject of a series of epic poems in Sumerian literature. However, he is described in these tablets as king of Uruk, the title given by the King List to Dumuzid the Fisherman - a distinct figure said to have ruled sometime after the Flood, in between Lugalbanda "the Shepherd" and Gilgamesh.

Among the mythical compositions involving Dumuzid the Shepherd are:

Inanna's descent to the netherworld: Inanna, after descending to the underworld, is allowed to return, but only with an unwanted entourage of demons, who insist on taking away a notable person in her place. She dissuades the demons from taking the rulers of Umma and Bad-tibira, who are sitting in dirt and rags. However, when they come to Uruk, they find Dumuzid the Shepherd sitting in palatial opulence, and seize him immediately, taking him into the underworld as Inanna's substitute.

Dumuzid and Ngeshtin-ana: Inanna gives Dumuzid over to the demons as her substitute; they proceed to violate him, but he escapes to the home of his sister, Ngeshtin-ana (Geshtinanna). The demons pursue Dumuzid there, and eventually find him hiding in the pasture.

Dumuzid and his sister: Fragmentary. Dumuzid's sister seems to be mourning his death in this tablet.

Dumuzid's dream: In this account, Dumuzid dreams of his own death and tells Ngeshtin-ana, who tells him it is a sign that he is about to be toppled in an uprising by evil and hungry men (also described as galla, 'demons') who are coming to Uruk for the king. No sooner does she speak this, than men of Adab, Akshak, Uruk, Ur, and Nibru are indeed sighted coming for him with clubs. Dumuzid resolves to hide in the district of Alali, but they finally catch him. He escapes from them and reaches to the district of Kubiresh, but they catch him again. Escaping again to the house of Old Woman Belili, he is again caught, but then escapes once more to his sister's home. There he is caught a last time, hiding in the pasture, and killed.

Inanna and Bilulu: This describes how Inanna avenges her lover Dumuzid's death, by killing Old Woman Bilulu (or Belili).

In a chart of antediluvian generations in Babylonian and Biblical traditions, William Wolfgang Hallo associates Dumuzid with the composite half-man, half-fish counselor or culture hero (Apkallu) An-Enlilda, and suggests an equivalence between Dumuzid and Enoch in the Sethite Genealogy given in Genesis chapter 5

Inanna would play Isis and Ishtar, among others.

Ishtar Eshnunna at the Louvre

British Museum Queen of the Night

Ishtar is the Akkadian counterpart to the Sumerian Inanna and to the cognate northwest Semitic goddess Astarte. Anunit, Astarte and Atarsamain are alternative names for Ishtar. Inanna, twin of Utu/Shamash, children of Nannar/Sin, first born on Earth of Enlil. The first names given are Sumerian, the second names derive from the Akkadians, who are a Semitic people who immigrated into Sumeria. Adding an [sh] to a name is typical Akkadian, as Anu to Anush.

The goddess represents the planet Venus. (A continent on Venus is named Ishtar Terra by astronomers today.) The double aspect of the goddess may correspond to the difference between Venus as a morning star and as an evening star. In Sumerian the planet is called "MUL.DILI.PAT" meaning "unique star".

The name Inanna (sometimes spelled Inana) means "Great Lady of An", where An is the god of heaven. The meaning of Ishtar is not known, though it is possible that the underlying stem is the same as that of Assur, which would thus make her the "leading one" or "chief". In any event, it is now generally recognized that the name is Semitic in origin.

The Sumerian Inanna was first worshiped at Uruk (Erech in the Bible, Unug in Sumerian) in the earliest period of Mesopotamian history. In incantations, hymns, myths, epics, votive inscriptions, and historical annals, Inanna/Ishtar was celebrated and invoked as the force of life. But there were two aspects to this goddess of life. She was the goddess of fertility and sexuality, and could also destroy the fields and make the earth's creatures infertile. She was invoked as a goddess of war, battles, and the chase, particularly among the warlike Assyrians. Before the battle Ishtar would appear to the Assyrian army, clad in battle array and armed with bow and arrow. (compare Greek Athena.)

One of the most striking Sumerian myths describes Inanna passing through seven gates of hell into the underworld. At each gate some of her clothing and her ornaments are removed until at the last gate she is entirely naked. Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld kills her and hangs her corpse on a hook on the wall. When Inanna returns from the underworld by intercession of the clever god, her uncle, Enki, according to the rules she must find someone to take her place. On her way home she encounters her friends prostrated with grief at her loss, but in Kulaba, her cult city, she finds her lover Dumuzi, a son of Enki, Tammuz seated in splendour on a throne, so she has him seized and dragged below. Later, missing him, she arranges for his sister to substitute for him during six months of the year.

In all the great centres Inanna and then Ishtar had her temples: E-anna, "house of An", in Uruk; E-makh, "great house", in Babylon; E-mash-mash, "house of offerings", in Nineveh. Inanna was the guardian of prostitutes, and probably had priestess-prostitutes to serve her. She was served by priests as well as by priestesses. The (later) votaries of Ishtar were virgins who, as long as they remained in her service, were not permitted to marry.

Inanna was also associated with beer, and was the patroness of tavern keepers, who were usually female in early Mesopotamia.

Ishtar is also an omnipresent figure in the epic of Gilgamesh. She appears also on the Uruk vase, one of the most famous ancient Mesopotamian artifacts. The relief on this vase seems to show Inanna conferring kingship on a supplicant. Various inscriptions and artifacts indicate that kingship was one of the gifts bestowed by Inanna on the ruler of Uruk.

On monuments and seal-cylinders Inanna/Ishtar appears frequently with bow and arrow, though also simply clad in long robes with a crown on her head and an eight-rayed star as her symbol. Statuettes have been found in large numbers representing her as naked with her arms folded across her breast or holding a child.

Together with the moon god Nanna or Suen (Sin in Akkadian), and the sun god Utu (Shamash in Akkadian), Inanna/Ishtar is the third figure in a triad deifying and personalizing the moon, the sun, and the earth: Moon (wisdom), Sun (justice) and Earth (life force). This triad overlies another: An, heaven; Enlil, earth; and Enki (Ea in Akkadian), the watery deep.

Symbol: an eight or sixteen-pointed star Sacred number: 15 Astrological region: Dibalt(Venus) and the Bowstar (Sirius) Sacred animal: lion, (dragon)

[Red Circles]

Snake-Dragon, Symbol of Marduk, the Patron God of Babylon.

Panel from the Ishtar Gate, 604-562 BCE, glazed earthenware bricks.

The Ishtar Gate survives today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

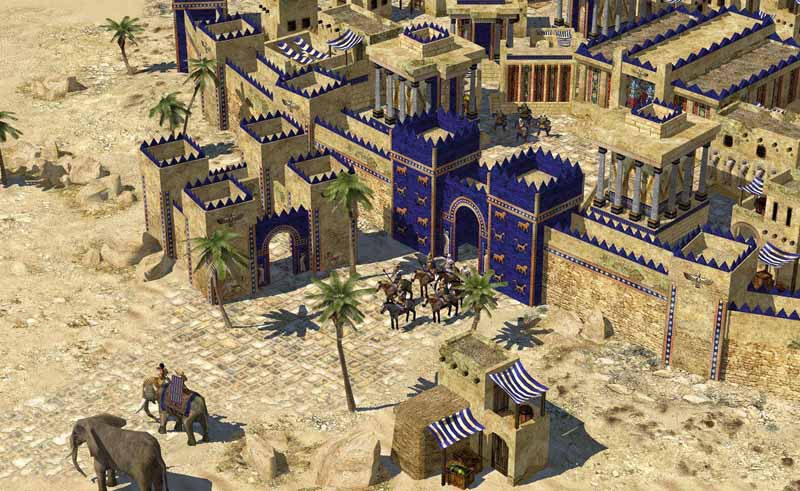

The Ishtar Gate was the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon (in the area of present-day Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq). It was constructed c. 575 BC by order of King Nebuchadnezzar II on the north side of the city. It was part of a grand walled processional way leading into the city.

The original structure was a double gate with a smaller frontal gate and a larger and more grandiose secondary posterior section. The walls were finished in glazed bricks mostly in blue, with animals and deities (also made up of colored bricks) in low relief at intervals. The gate was 50 feet (15 meters) high, and the original foundations extended another 45 feet (14 meters) underground.

German archaeologist Robert Koldewey led the excavation of the site from 1904 to 1914. After the end of the First World War in 1918, the smaller frontal gate was reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Other panels from the facade of the gate are located in many other museums around the world. The facade of the Iraqi embassy in Beijing, China includes a replica of the Ishtar Gate. The facade of the Iraqi embassy in Amman, Jordan also evokes the Ishtar Gate. Continue reading

Babylon's Ishtar Gate may have a totally different purpose than we thought, magnetic field measurements suggest Live Science - January 18, 2024

Babylon's bright-blue Ishtar Gate was thought to have been built to celebrate the conquest of Jerusalem - but a new analysis finds that it may have been erected years later. The iconic glazed-brick edifice, which King Nebuchadnezzar II ordered to be built and decorated with wild bulls and mushussu-dragons while ruling the Babylonian empire from 605 to 562 B.C., was constructed in three phases and served as the entrance to the ancient city of Babylon, located in southern Mesopotamia. However, the exact dates of each construction phase have long been up for debate. While it's known that Nebuchadnezzar II ordered the first phase, as these bricks are inscribed with his name, it was less clear if some time had passed before the second and third phases were completed, according to the study. Some researchers even wondered if Nebuchadnezzar II had died before the gate's completion.

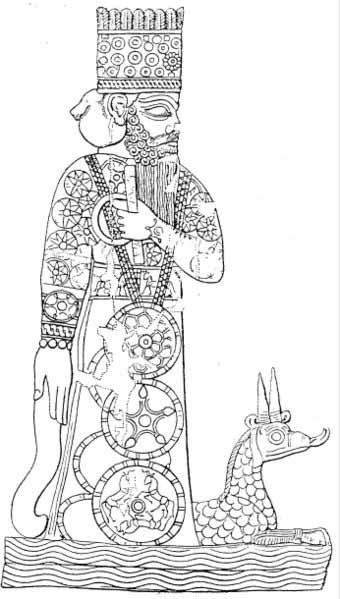

Marduk (Sumerian spelling in Akkadian AMAR.UTU "solar calf"; Biblical Merodach) was the name of a late generation god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon, who, when Babylon permanently became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of Hammurabi (18th century BC), started to slowly rise to the position of the head of the Babylonian pantheon, position he fully acquired by the second half of the second millennium BCE.

Marduk's original character is obscure, but whatever special traits Marduk may have had were overshadowed by the reflex of the political development through which the Euphrates valley passed and which led to imbuing him with traits belonging to gods who at an earlier period were recognized as the heads of the pantheon.

There are more particularly two gods - Ea and Enlil - whose powers and attributes pass over to Marduk. In the case of Ea the transfer proceeds pacifically and without involving the effacement of the older god. Marduk is viewed as the son of Ea. The father voluntarily recognizes the superiority of the son and hands over to him the control of humanity. This association of Marduk and Ea, while indicating primarily the passing of the supremacy once enjoyed by Eridu to Babylon as a religious and political centre, may also reflect an early dependence of Babylon upon Eridu, not necessarily of a political character but, in view of the spread of culture in the Euphrates valley from the south to the north, the recognition of Eridu as the older centre on the part of the younger one.

While the relationship between Ea and Marduk is thus marked by harmony and an amicable abdication on the part of the father in favor of his son, Marduk's absorption of the power and prerogatives of Enlil of Nippur was at the expense of the latter's prestige. After the days of Hammurabi, the cult of Marduk eclipses that of Enlil, and although during the four centuries of Kassite control in Babylonia (c. 1570 BC-1157 BC), Nippur and the cult of Enlil enjoyed a period of renaissance, when the reaction ensued it marked the definite and permanent triumph of Marduk over Enlil until the end of the Babylonian empire. The only serious rival to Marduk after ca. 1000 BC is Anshar in Assyria. In the south Marduk reigns supreme. He is normally referred to as Bel "Lord".

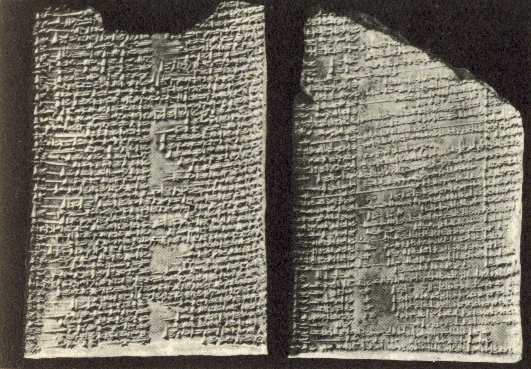

Enuma Elish

When Babylon became the capital of Mesopotamia, the patron deity of Babylon was elevated to the level of supreme god. In order to explain how Marduk seized power, Enuma Elish, was written, which tells the story of Marduk's birth, heroic deeds, and becoming the ruler of the gods. This can be viewed as a form of Mesopotamian apologetics.

In Enuma Elish a civil war between the gods was growing to a climatic battle. The Anunnaki gods gathered together to find one god who could defeat the gods rising against them. Marduk, a very young god, answered the call, and was promised the position of head god.When he killed his enemy he "wrested from him the Tablets of Destiny, wrongfully his" and assumed his new position. Under his reign humans were created to bear the burdens of life so the gods could be at leisure.

People were named after Marduk. For example, the Biblical personality Mordechai (Book of Esther) used this Gentile name in replacement of his Hebrew name Bilshan.Ba bylonian texts talk of the creation of Eridu by the god Marduk as the first city, 'the holy city, the dwelling of their the other gods delight'.

Nabu, god of wisdom, is a son of Marduk.

Etemenanki, "The temple of the creation of heaven and earth", was the name of a ziggurat to Marduk in the city of Babylon of the 6th century BC Chaldean (Neo-Babylonian) dynasty. Originally seven stories in height, little remains of it now save ruins. Etemenanki was later popularly identified with the Tower of Babel.

In Sumerian mythology, Nammu (more properly Namma) was a primeval goddess, corresponding to Tiamat in Babylonian mythology. Taimat was a primordial goddess who rose from the void and created the collective unconsciousness.

Nammu was the primeval sea (Engur) that gave birth to An (heaven) and Ki (earth) and the first gods, representing the Apsu, the fresh water ocean that the Sumerians believed lay beneath the earth, the source of life-giving water and fertility in a country with almost no rainfall.

Nammu is not well attested in Sumerian mythology. She may have been of greater importance prehistorically, before Enki took over most of her functions. An indication of her continued relevance may be found in the theophoric name of Ur-Nammu, the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur. According to the Neo-Sumerian mythological text Enki and Ninmah, Enki is the son of An and Nammu. Nammu is the goddess who "has given birth to the great gods". It is she who has the idea of creating mankind, and she goes to wake up Enki, who is asleep in the Apsu, so that he may set the process going.

Nammu and the Tree of Life at Ur

Steal of Ur-Nammu at Ur

Ur-Nammu founded the Sumerian 3rd dynasty of Ur, in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries of Akkadian and Gutian rule. His main achievement was state-building, and Ur-Nammu is chiefly remembered today for his legal code, the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known surviving example in the world.

Nergal refers to a deity in Babylon with the main seat of his cult at Cuthah represented by the mound of Tell-Ibrahim. Nergal is mentioned in the Hebrew bible as the deity of the city of Cuth (Cuthah): "And the men of Babylon made Succoth-benoth, and the men of Cuth made Nergal" (2 Kings, 17:30). According to the rabbins, his emblem was a cock and Nergal means a "dunghill cock". He is the son of Enlil and Ninlil.

Nergal actually seems to be in part a solar deity, sometimes identified with Shamash, but a representative of a certain phase only of the sun. Portrayed in hymns and myths as a god of war and pestilence, Nergal seems to represent the sun of noontime and of the summer solstice which brings destruction to mankind, high summer being the dead season in the Mesopotamian annual cycle.

Nergal was also the deity who presides over the nether-world, and who stands at the head of the special pantheon assigned to the government of the dead (supposed to be gathered in a large subterranean cave known as Aralu or Irkalla). In this capacity he has associated with him a goddess Allatu or Ereshkigal, though at one time Allatu may have functioned as the sole mistress of Aralu, ruling in her own person. In some texts the god Ninazu is the son of Nergal by Allatu/Ereshkigal.

Ordinarily Nergal pairs with his consort Laz. Standard iconography pictured Nergal as a lion, and boundary-stone monuments symbolise him with a mace surmounted by the head of a lion.

Nergal's fiery aspect appears in names or epithets such as Lugalgira, Sharrapu ("the burner," perhaps a mere epithet), Erra, Gibil (though this name more properly belongs to Nusku), and Sibitti. A certain confusion exists in cuneiform literature between Ninurta and Nergal. Nergal has epithets such as the "raging king," the "furious one," and the like. A play upon his name separated into three elements as Ne-uru-gal (lord of the great dwelling) expresses his position at the head of the nether-world pantheon.

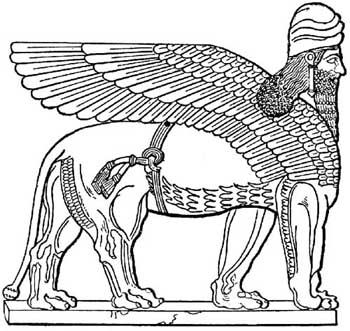

In the astral-theological system Nergal becomes the planet Mars, while in ecclesiastical art the great lion-headed colossi serving as guardians to the temples and palaces seem to symbolise Nergal, just as the bull-headed colossi probably typify Ninurta.

Nergal's chief temple at Cuthah bore the name Meslam, from which the god receives the designation of Meslamtaeda or Meslamtaea, "the one that rises up from Meslam". The name Meslamtaeda/Meslamtaea indeed is found as early as the list of gods from Fara while the name Nergal only begins to appear in the Akkadian period.

The cult of Nergal does not appear to have spread as widely as that of Ninurta. Hymns and votive and other inscriptions of Babylonian and Assyrian rulers frequently invoke him, but we do not learn of many temples to him outside of Cuthah. Sennacherib speaks of one at Tarbisu to the north of Nineveh, but significantly, although Nebuchadnezzar II (606 BC 586 BC), the great temple-builder of the neo-Babylonian monarchy, alludes to his operations at Meslam in Cuthah, he makes no mention of a sanctuary to Nergal in Babylon. Local associations with his original seat Kutha and the conception formed of him as a god of the dead acted in making him feared rather than actively worshipped.

Shamash or Sama, was the common Akkadian name of the sun-god in Babylonia and Assyria, corresponding to Sumerian Utu.

The name signifies perhaps "servitor," and would thus point to a secondary position occupied at one time by this deity. Both in early and in late inscriptions Sha-mash is designated as the "offspring of Nannar," i.e. of the moon-god, and since, in an enumeration of the pantheon, Sin generally takes precedence of Shamash, it is in relationship, presumably, to the moon-god that the sun-god appears as the dependent power.

Such a supposition would accord with the prominence acquired by the moon in the calendar and in astrological calculations, as well as with the fact that the moon-cult belongs to the nomadic and therefore earlier, stage of civilization, whereas the sun-god rises to full importance only after the agricultural stage has been reached.

The two chief centres of sun-worship in Babylonia were Sippar, represented by the mounds at Abu Habba, and Larsa, represented by the modern Senkerah. At both places the chief sanctuary bore the name E-barra (or E-babbara) "the shining house" a direct allusion to the brilliancy of the sun-god. Of the two temples, that at Sippara was the more famous, but temples to Shamash were erected in all large centres such as Babylon, Ur, Mari, Nippur and Nineveh.

The attribute most commonly associated with Shamash is justice. Just as the sun disperses darkness, so Shamash brings wrong and injustice to light. Hammurabi attributes to Shamash the inspiration that led him to gather the existing laws and legal procedures into a code, and in the design accompanying the code the king represents himself in an attitude of adoration before Shamash as the embodiment of the idea of justice.

Several centuries before Hammurabi, Ur-Engur of the Ur dynasty (c. 2600 BC) declared that he rendered decisions "according to the just laws of Shamash."

It was a logical consequence of this conception of the sun-god that he was regarded also as the one who released the sufferer from the grasp of the demons. The sick man, therefore, appeals to Shamash as the god who can be depended upon to help those who are suffering unjustly. This aspect of the sun-god is vividly brought out in the hymns addressed to him, which are, therefore, among the finest productions in the entire realm of Babylonian literature.

It is evident from the material at our disposal that the Shamash cults at Sippar and Larsa so overshadowed local sun-deities elsewhere as to lead to an absorption of the minor deities by the predominating one. In the systematized pantheon these minor sun-gods become attendants that do his service. Such are Bunene, spoken of as his chariot driver, whose consort is Atgi-makh, Kettu ("justice") and Mesharu ("right"), who are introduced as servitors of Shamash.

Other sun-deities, as Ninurta and Nergal, the patron deities of important centres, retained their independent existence as certain phases of the sun, Ninib becoming the sun-god of the morning and of the spring time, and Nergal the sun-god of the noon and of the summer solstice, while Shamash was viewed as the sun-god in general.

Together with Sin and Ishtar, Shamash forms a second triad by the side of Anu, Enlil and Ea. The three powers, Sin, Shamash and Ishtar, symbolized the three great forces of nature, the sun, the moon and the life-giving force of the earth.

At times, instead of Ishtar, we find Adad, the storm-god, associated with Sin and Shamash, and it may be that these two sets of triads represent the doctrines of two different schools of theological thought in Babylonia which were subsequently harmonized by the recognition of a group consisting of all four deities.

The consort of Shamash was known as A. She, however, is rarely mentioned in the inscriptions except in combination with Shamash.

Impression of the cylinder seal of Hashamer - High Priest of Sin at Iskun Sin ca. 2100 BC. The seated figure is probably king Ur-Nammu, bestowing the governorship on Hashamer, who is led before him by a lamma (protective goddess). Sin/Nanna himself is present in the form of a crescent.

Sin was the god of the moon in Mesopotamian mythology. Nanna is a Sumerian deity, the son of Enlil and Ninlil, and became identified with Semitic Sin. The two chief seats of Nanna's/Sin's worship were Ur in the south of Mesopotamia and Harran in the north.

He is commonly designated as En-zu, which means "lord of wisdom". During the period (c.2600-2400 BCE) that Ur exercised a large measure of supremacy over the Euphrates valley, Sin was naturally regarded as the head of the pantheon. It is to this period that we must trace such designations of Sin as "father of the gods", "chief of the gods", "creator of all things", and the like. The "wisdom" personified by the moon-god is likewise an expression of the science of astronomy or the practice of astrology, in which the observation of the moon's phases is an important factor.

His wife was Ningal ("Great Lady"), who bore him Utu/Shamash ("Sun") and Inanna/Ishtar (the goddess of the planet Venus). The tendency to centralize the powers of the universe leads to the establishment of the doctrine of a triad consisting of Sin/Nanna and his children.

Sin had a beard made of lapis lazuli and rode on a winged bull. The bull was one of his symbols, through his father, Enlil, "Bull of Heaven", along with the crescent and the tripod (which may be a lamp-stand). On cylinder seals, he is represented as an old man with a flowing beard and the crescent symbol. In the astral-theological system he is represented by the number 30 and the moon. This number probably refers to the average number of days (correctly around 29.53) in a lunar month, as measured between successive new moons.

An important Sumerian text ("Enlil and Ninlil") tells of the descent of Enlil and Ninlil, pregnant with Nanna/Suen, into the underworld. There, three "substitutions" are given to allow the ascent of Nanna/Suen. The story shows some similarities to the text known as "The Descent of Inanna".

Nanna's chief sanctuary at Ur was named E-gish-shir-gal ("house of the great light"). It was at Ur that the role of the En Priestess developed. This was an extremely powerful role held by a princess, most notably Enheduanna, daughter of King Sargon of Akkad, and was the primary cult role associated with the cult of Nanna/Sin. Sin also had a sanctuary at Harran, named E-khul-khul ("house of joys"). The cult of the moon-god spread to other centers, so that temples to him are found in all the large cities of Babylonia and Assyria. A sanctuary for Sin with Syriac inscriptions invoking his name dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE was found at Sumatar Harabesi in the Tektek mountains, not far from Harran and Edessa.