A neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is so small that it was long thought to be zero. The mass of the neutrino is much smaller than that of the other known elementary particles. The weak force has a very short range, the gravitational interaction is extremely weak, and neutrinos do not participate in the strong interaction. Thus, neutrinos typically pass through normal matter unimpeded and undetected.

Neutrinos are fundamental particles that far outnumber all the atoms in the universe but rarely interact with other matter. Astrophysicists are particularly interested in high-energy neutrinos, which have energies up to 1,000 times greater than those produced by the most powerful particle colliders on Earth. They think the most extreme events in the universe, like violent galactic outbursts, accelerate particles to nearly the speed of light. Those particles then collide with light or other particles to generate high-energy neutrinos. The first confirmed high-energy neutrino source, announced in 2018, was a type of active galaxy called a blazar.

The latest measurements show that the number of light neutrino types (mass < 1MeV) is 2.984+0.008. This does not, however, exclude the possibility of a sterile neutrino, i.e. one that does not even interact by way of the weak nuclear force. Such a neutrino could only be created through flavor oscillation. The correspondence between the six - currently known - quarks in the Standard Model and the six leptons, among them the three neutrinos, provides additional evidence that there should be exactly three types. However, conclusive proof that there are only three kinds of neutrinos remains an elusive goal of particle physics.

Physicists Tighten the Net Around the Elusive Sterile Neutrino SciTech Daily - December 25, 2025

High-precision measurements from the KATRIN experiment strongly limit the existence of light sterile neutrinos and narrow the search for new physics. Neutrinos are extremely difficult to detect, yet they are some of the most abundant matter particles in the Universe. The Standard Model includes three known types, but discoveries showing that neutrinos oscillate revealed that they have mass and can change from one type to another as they move.

After more than a decade of design, construction, and international collaboration, JUNO has become the world's first next-generation, large-scale, high-precision neutrino detector to begin operation PhysOrg - November 19, 2025

Early data show that the detector's key performance indicators fully meet or surpass design expectations, confirming that JUNO is ready to deliver frontier measurements in neutrino physics.

When Neutron Stars Collide, Neutrinos Get Into The Mix Universe Today - November 6, 2025

The material of a neutron star is unlike anything we have on Earth. Rather than atoms and molecules, neutron stars are a dense sea of nuclear material, held together by gravity so intense that electrons and protons can be squeezed together to become neutrons. So there's much about the physics of neutron stars we still don't understand. It's complicated, as they say, and things get even worse when neutron stars collide.

It's Official: For The First Time Neutrinos Have Been Detected in a Collider Experiment Science Alert - September 27, 2023

The ghost, at long last, is actually in the machine. Earlier this year, for the first time, scientists detected neutrinos created in a particle collider. Those abundant yet enigmatic subatomic particles are so removed from the rest of matter that they slide through it like specters, earning them the nickname "ghost particles". The researchers said this work represented the first direct observation of collider neutrinos and would help us to understand how these particles form, what their properties are, and their role in the evolution of the Universe.

Deciphering the Mystery of Neutrino Mass - A New Approach Uses Random Matrix Theory SciTech Daily - July 5, 2023

Beyond the remaining mysteries of the Standard Model, there is a whole new world of physics.

Neutrino map of the galaxy is 1st view of the Milky Way in anything other than light Live Science - June 30, 2023

Scientists at the IceCube Neutrino Observatory have used 60,000 neutrinos to create the first map of the Milky Way made with matter and not light. Scientists have traced the galactic origins of thousands of "ghost particles" known as neutrinos to create the first-ever portrait of the Milky Way made from matter and not light - and it's given them a brand-new way to study the universe.

Milky Way: Icy observatory reveals 'ghost particles' BBC - June 30, 2023

An astronomical detector buried in Antarctic ice has provided a view of our Galaxy that has never been seen before. The blurry, extraordinary image is of the Milky Way, but it is composed of the "ghostly" particles that are emitted by the reactions that power stars. The particles are neutrinos, which are extremely difficult to detect on Earth. To find them, scientists turned a vast block of Antarctic ice into a detector.

High-Energy Neutrinos From Inside Our Own Galaxy Hint at The Origin of Cosmic Rays Science Alert - June 29, 2023

Somewhere out in the depths of the Milky Way galaxy, something stirs. Powerful forces whip charged particles into an energetic frenzy of cosmic rays, launching them at velocities that near the speed of light. We may finally be close to pinning down their origins. A reanalysis of 10 years of data collected by the the IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica has returned the most solid evidence to date of neutrino emissions from the center of our galaxy that point to long-sought sources of cosmic rays.

Physicists get closer than ever to measuring the elusive neutrino Live Science - February 22, 2022

Ghost-like particles called neutrinos hardly ever interact with normal matter, giving the teensy apparitions supreme hiding powers. They are so elusive that, in the decades since their initial discovery, physicists still haven't pinned down their mass. But recently, by plopping them onto a 200-ton "neutrino scale," scientists have put a new limit on the neutrino's mass. The result: It's very, very small.

For The First Time, We've Detected a 'Ghost Particle' Coming From a Shredded Star Science Alert - February 25, 2021

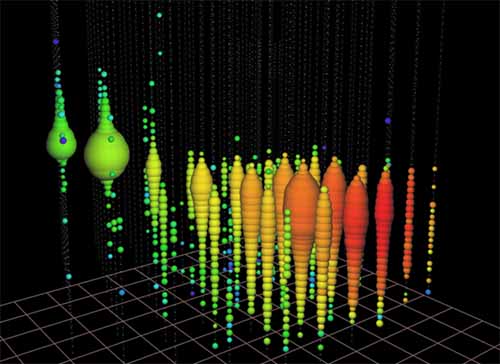

A star completely torn apart when it ventured too close to a black hole has given science a rare gift. For the first time, scientists have detected a high-energy neutrino that was flung out into space during one of these violent events. The tiny particle doesn't just get us closer to figuring out where precisely the most energetic particles in the Universe are born; it shows that black hole tidal disruption events can produce powerful natural particle accelerators. Neutrinos are fascinating little things. Their mass is almost zero, they travel at near light-speed, and they don't really interact with normal matter; to a neutrino, the Universe would be all but incorporeal. In fact, billions of neutrinos are zooming through you right now. This is why they have been nicknamed the 'ghost particle'. This doesn't mean they can't interact with matter, though, and this is how IceCube detects them. Every now and again, a neutrino can interact with the ice and create a flash of light. With detectors tunneled deep into the darkness in the Antarctic ice, those flashes really stand out.

NASA's Swift Helps Tie Neutrino to Star-shredding Black Hole NASA - February 25, 2021

Watch how a monster black hole ripping apart a star may have launched a ghost particle toward Earth. Astronomers have long predicted that tidal disruption events could produce high-energy neutrinos, nearly massless particles from outside our galaxy traveling close to the speed of light. One recent event, named AT2019dsg, provides the first proof this prediction is true but has challenged scientists' assumptions of where and when these elusive particles might form during these destructive outbursts.

Ghost particle travels 750 million light-years, ends up buried under the Antarctic ice Live Science - February 25, 2021

For the first time ever, scientists have received mysteriously delayed signals from two supermassive black holes that snacked on stars in their vicinity. In the first case, a black hole weighing as much as 30 million suns located in a galaxy approximately 750 million light-years away gobbled up a star that passed too close to its edge. Light from the event was spotted in April 2019, but six months later a telescope in Antarctica captured an extremely high-energy and ghostly particle - a neutrino - that was apparently burped out during the feast.

Mysterious high-energy event in IceCube could be a tau neutrino Physics World - July 12, 2018

Scientists trace a single neutrino back to a galaxy billions of light years away Science Daily - July 12, 2018

Using an internationally organized astronomical dragnet, scientist have for the first time located a source of high-energy cosmic neutrinos, ghostly elementary particles that travel billions of light years through the universe, flying unaffected through stars, planets and entire galaxies.

The neutrino was first postulated in 1931 by Wolfgang Pauli to explain the energy spectrum of beta decays, the decay of a neutron into a proton and an electron. Pauli theorized that an undetected particle was carrying away the observed difference between the energy and angular momentum of the initial and final particles. Because of their "ghostly" properties, the first experimental detection of neutrinos had to wait until about 25 years after they were first discussed. In 1956 Clyde Cowan, Frederick Reines, F. B. Harrison, H. W. Kruse, and A. D. McGuire published the article "Detection of the Free Neutrino: a Confirmation" in Science (see neutrino experiment), a result that was rewarded with the 1995 Nobel Prize. The name neutrino was coined by Enrico Fermi - who developed the first theory describing neutrino interactions - as a word play on neutrone, the Italian name of the neutron. (Neutrone in Italian means big and neutral, and neutrino means small and neutral.)

In 1962 Leon M. Lederman, Melvin Schwartz and Jack Steinberger showed that more than one type of neutrino exists by first detecting interactions of the muon neutrino. When a third type of lepton, the tauon, was discovered in 1975 at the Stanford Linear Accelerator, it too was expected to have an associated neutrino. First evidence for this third neutrino type came from the observation of missing energy and momentum in tau decays analogous to the beta decay that had led to the discovery of the neutrino in the first place. The first detection of actual tau neutrino interactions was announced in summer of 2000 by the DONUT collaboration at Fermilab, making it the latest particle of the Standard Model to have been directly observed.

The basic Standard Model of particle physics assumes that the neutrino is massless, although adding massive neutrinos to the basic framework is not difficult, and recent experiments suggest that the neutrino has a small non-zero mass.

The strongest upper limits on the mass of the neutrino come from cosmology. The Big Bang model predicts that there is a fixed ratio between the number of neutrinos and the number of photons in the cosmic microwave background. If the total mass of all three types of neutrinos exceeded 50 electron volts (per neutrino), there would be so much mass in the universe that it would collapse. This limit can be circumvented by assuming that the neutrino is unstable; however, there are limits within the Standard Model that make this difficult.

However, it is now widely believed that the mass of the neutrino is non-zero. When one extends the Standard Model to include neutrino masses, one finds that massive neutrinos can change type whereas massless neutrinos cannot. This phenomenon, known as neutrino oscillation, explains why there are many fewer electron neutrinos observed from the sun and the upper atmosphere than expected, and has also been directly observed.

Nuclear power stations are the major source of human generated neutrinos. An average plant may generate over 1020 anti-neutrinos per second.

Some particle accelerators have been used to make neutrino beams. Their technique is to smash protons into a fixed target, producing charged pions or kaons. These unstable particles are then beamed into a long tunnel where they decay while in flight. Because of the relativistic boost of the decaying particle the neutrinos are produced as a beam rather than isotropically.

Nuclear bombs also produce very large numbers of neutrinos. Fred Reines and Clyde Cowan thought about trying to detect neutrinos from a bomb before they switched to looking for reactor neutrinos.

The Earth

Neutrinos are produced as a result of natural background radiation.

Atmospheric Neutrinos

Atmospheric neutrinos result from the interaction of cosmic rays with atoms in the Earth's atmosphere, creating showers of particles, many of which are unstable and produce neutrinos when they decay.

Solar Neutrinos

Solar neutrinos originate from the nuclear fusion powering the Sun and other stars.

Cosmological Phenomena

Neutrinos are an important product of supernovas. Most of the energy produced in supernovas is radiated away in the form of an immense burst of neutrinos, which are produced when protons and electrons in the core combine to form neutrons. The first experimental evidence of this phenomenon came in the year 1987, when neutrinos coming from the supernova 1987a were detected. In such events, the densities at the core become so high (1014 g/cm3) that interaction between the produced neutrinos and surrounding stellar matter becomes significant. It is thought that neutrinos would also be produced from other events such as the collision of neutron stars.

Because neutrinos interact so little with matter, it is thought that a supernova's neutrino emissions carry information about the innermost regions of the explosion. Much of the visible light comes from the decay of radioactive elements produced by the supernova shock wave, and even light from the explosion itself is scattered by dense and turbulent gases. Neutrinos, on the other hand, pass through these gases, providing information about the supernova core (where the densities were large enough to influence the neutrino signal). Furthermore, the neutrino burst is expected to reach Earth before any electromagnetic waves, including visible light, gamma rays or radio waves. The exact time delay is unknown, but for a Type II supernova, astronomers expect the neutrino flood to be released seconds after the stellar core collapse, while the first electromagnetic signal may be hours or days later. The SNEWS project uses a network of neutrino detectors to monitor the sky for candidate supernova events; it is hoped that the neutrino signal will provide a useful advance warning of an exploding star.

Cosmic background radiation

It is thought that the cosmic background radiation left over from the Big Bang includes a background of low energy neutrinos. In the 1980s it was proposed that these may be the explanation for the dark matter thought to exist in the universe. Neutrinos have one important advantage over most other dark matter candidates: we know they exist. However, they also have serious problems. From particle experiments, it is known that neutrinos tend to be hot, i.e. move at speeds close to the speed of light - hence this scenario was also known as hot dark matter. The problem is that being hot and fast moving, the neutrinos would tend to spread out evenly in the universe. This would tend to cause matter to be smeared out and prevent the large galactic structures that we see.

There are several types of neutrino detectors. Those used to detect stellar neutrinos consist of a large amount of material in an underground cave designed to shield it from cosmic radiation.

In 1953 the first neutrino detection device was used to detect neutrinos near a nuclear reactor. Reines and Cowan used two targets containing a solution of cadmium chloride in water. Two scintillation detectors were placed next to the cadmium targets. Neutrino interactions with protons of the water produced positrons. The resulting positron annihilations with electrons created photons with an energy of about 0.5 MeV. Pairs of photons in coincidence could be detected by the two scintillation detectors above and below the target. The neutrons were captured by cadmium nuclei resulting in gamma rays of about 8 MeV that were detected a few microseconds after the photons from a positron annihilation event.

Chlorine detectors consist of a tank filled with carbon tetrachloride. In these detectors a neutrino would convert a chlorine atom into one of argon. The fluid would periodically be purged with helium gas which would remove the argon. The helium would then be cooled to separate out the argon. These detectors had the failing that it was impossible to determine the direction of the incoming neutrino. It was the chlorine detector in the former Homestake Mine near Lead, South Dakota, containing 520 short tons (470 metric tons) of fluid, which first detected the deficit of neutrinos from the sun that led to the solar neutrino problem. This type of detector is only sensitive to electron neutrinos.

Gallium detectors are similar to chlorine detectors but more sensitive to low-energy neutrinos. A neutrino would convert gallium to germanium which could then be chemically detected. Again, this type of detector provides no information on the direction of the neutrino.

Pure water detectors such as Super-Kamiokande contain a large area of pure water surrounded by sensitive light detectors known as photomultiplier tubes. In this detector, the neutrino transfers its energy to an electron which then travels faster than the speed of light in the medium (though slower than the speed of light in a vacuum). This generates an "optical shockwave" known as Cherenkov radiation which can be detected by the photomultiplier tubes. This detector has the advantage that the neutrino is recorded as soon as it enters the detector, and information about the direction of the neutrino can be gathered. It was this type of detector that recorded the neutrino burst from supernova 1987a. This type of detector is sensitive to electron and muon neutrinos.

Heavy water detectors use three types of reactions to detect the neutrino. The first is the same reaction as pure water detectors. The second involves the neutrino striking the deuterium atom releasing an electron. The third involves the neutrino breaking the deuterium atom into two. The results of these reactions can be detected by photomultiplier tubes. This type of detector is in operation in the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO). This type of detector is sensitive to all three neutrino flavors.

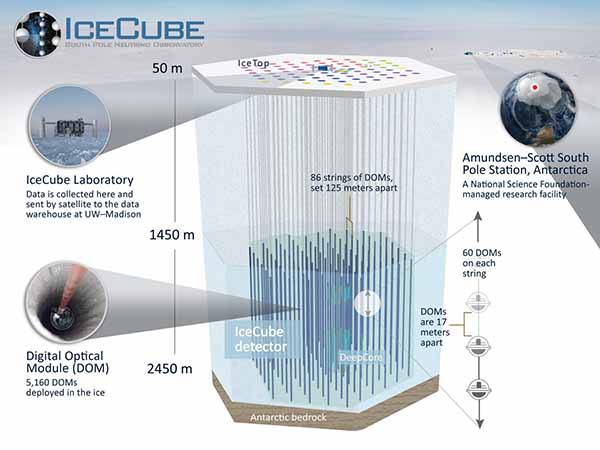

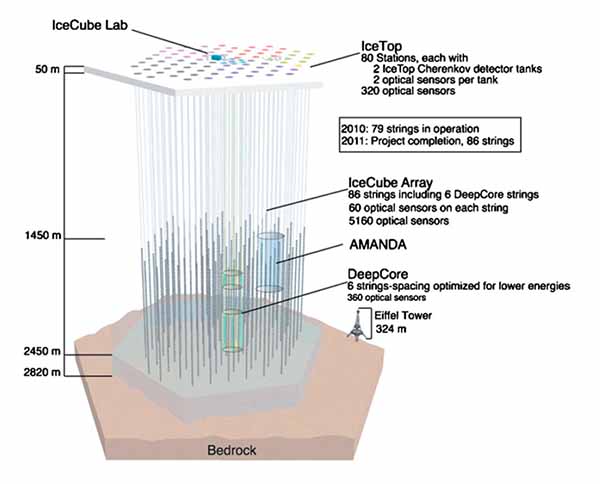

On October 1, 2019, the National Science Foundation's IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica detected a high-energy neutrino called IC191001A and backtracked along its trajectory to a location in the sky. IceCube is designed to look for point sources of neutrinos in the TeV range to explore the highest-energy astrophysical processes.

The neutrino is of scientific interest because it can make an exceptional probe for environments that are typically concealed from the standpoint of other observation techniques, such as optical and radio observation.

The first such use of neutrinos was proposed in the early 20th century for observation of the core of the Sun. Direct optical observation of the solar core is impossible due to the diffusion of electromagnetic radiation by the huge amount of matter surrounding the core. On the other hand, neutrinos generated in stellar fusion reactions are very weakly interacting and therefore pass right through the sun with few or no interactions. While photons emitted by the solar core may require 1,000 years to diffuse to the outer layers of the Sun, neutrinos are virtually unimpeded and cross this distance at nearly the speed of light.

Neutrinos are also useful for probing astrophysical sources beyond our solar system. Neutrinos are the only known particles that are not significantly attenuated by their travel through the interstellar medium. Optical photons can be obscured or diffused by dust, gas and background radiation. High-energy cosmic rays, in the form of fast-moving protons and atomic nuclei, are not able to travel more than about 100 megaparsecs due to the GZK cutoff. Neutrinos can travel this distance, and greater distances, with very little attenuation.

The galactic core of the Milky Way is completely obscured by dense gas and numerous bright objects. However, it is likely that neutrinos produced in the galactic core will be measurable by Earth based neutrino telescopes in the next decade.

The most important use of the neutrino is in the observation of supernovae, the explosions that end the lives of highly massive stars. The core collapse phase of a supernova is an almost unimaginably dense and energetic event. It is so dense that no known particles are able to escape the advancing core front except for neutrinos. Consequently, supernovae are known to release approximately 99% of their energy in a rapid (10 second) burst of neutrinos. As a result, the usefulness of neutrinos as a probe for this important event in the death of a star can not be overstated.

Many other important uses of the neutrino may be imagined in the future. It is clear that the astrophysical significance of the neutrino as an observational technique is comparable with all other known techniques, and is therefore a major focus of study in astrophysical communities.