The Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis) was a species of the Homo genus that inhabited Europe and parts of western Asia from about 230,000 to 29,000 years ago, during the Middle Paleolithic period. They became extinct about 40,000 years ago. Neanderthals and modern humans share 99.7% of their DNA and are hence closely related. (By comparison, both modern humans and Neanderthals share 98.8% of their DNA with their closest non-human living relatives, the chimpanzees.) Neanderthals left bones and stone tools in Eurasia, from Western Europe to Central and Northern Asia. Fossil evidence suggests Neanderthals evolved in Europe, separate from modern humans in Africa for more than 400,000 years. They are considered either a distinct species, Homo neanderthalensis, or more rarely as a subspecies of Homo sapiens (H. s. neanderthalensis). Read more

Neanderthals were humans (a distinct species or subspecies of Homo). They made tools, used fire, buried their dead, and possibly created art - all signs of culture and behavior studied by archaeologists. However, their bones are studied in a branch of science called Paleoanthropology - which is part of physical anthropology, not paleontology.

Neanderthal discoveries are mainly archaeology, with strong overlap into paleoanthropology, and sometimes paleontology when studying their environment or the extinct animals they hunted.

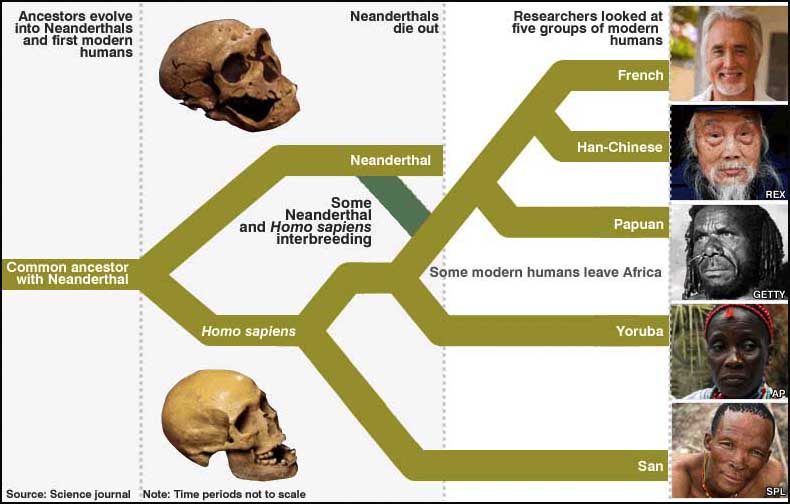

Ancient humans and Neanderthals interbred. Around 60,000-40,000 years ago, modern Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa and spread into Europe and Asia - regions already inhabited by Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). When these two human species met, they didn't just compete - they also interbred. As a result, bits of Neanderthal DNA entered the modern human gene pool and were passed down through generations.

Most people with non-African ancestry - meaning primarily those from Europe, Asia, and the Americas - have about 1-2% Neanderthal DNA. People whose ancestors remained in sub-Saharan Africa usually have little to no Neanderthal DNA, because their lineages didn't go through that same interbreeding event (though there was some limited back-migration later).

The legacy of Neanderthals isn't just historical - it's literally written in our DNA. Many of those genes are neutral, but some have noticeable effects, such as:

- Immune system responses - certain Neanderthal genes help fight viruses and bacteria.

- Skin and hair traits - pigmentation and keratin genes helped early humans adapt to colder, darker climates.

- Health risks - a few are linked to allergies or autoimmune disorders.

- Sleep patterns and mood - some variants influence circadian rhythm and even susceptibility to depression.

Rather than Neanderthals being a different or lesser species, we now know they're part of our extended human family - close enough genetically to share love, offspring, and survival strategies. In a sense, they live on in us - a genetic memory of another kind of human who walked the Earth before history began.

Like many people who research their ancestry, I discovered what it could mean to have a DNA connection to Neanderthals.

Archaeologists Discover Earliest Evidence of Humans Using Tools to Make Fire Live Science - December 10, 2025

Archaeologists uncover evidence that Neanderthals made fire 400,000 years ago in England Live Science - December 10, 2025

First Neanderthal Footprints Found on Portugal's Coast Rewrite What We Know About Early Humans

A newly discovered Neanderthal site on Portugal's Algarve coast has revealed the first fossilized footprints of these ancient humans in the region.

World's Oldest Known Cave Art Was Made by Neanderthals Science Alert - November 5, 2025

However, at present, all of the Neanderthal evidence is non-figurative - they have no depictions of animals, including humans.

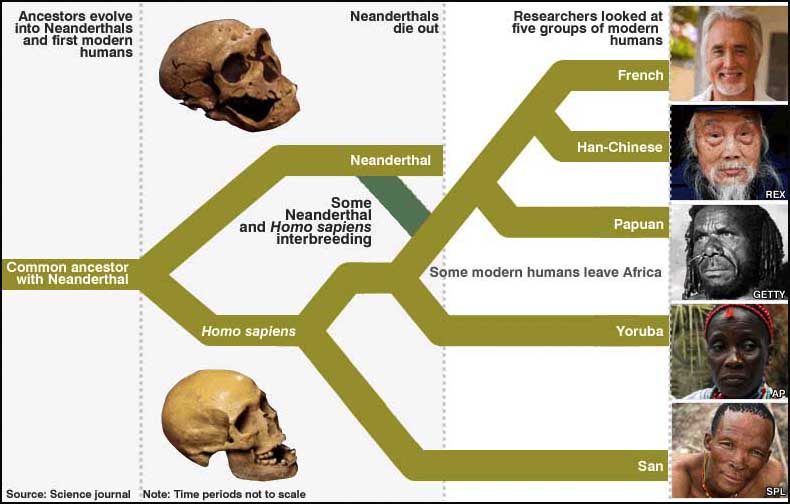

1 million-year-old skull from China holds clues to the origins of Neanderthals, Denisovans and humans Live Science - September 25, 2025

Researchers have virtually reconstructed a crushed and distorted 1 million-year-old human skull discovered in China. The newly restored cranium may have belonged to a relative of the mysterious Denisovans and provides clues to the rapid evolution of Homo sapiens in Asia.

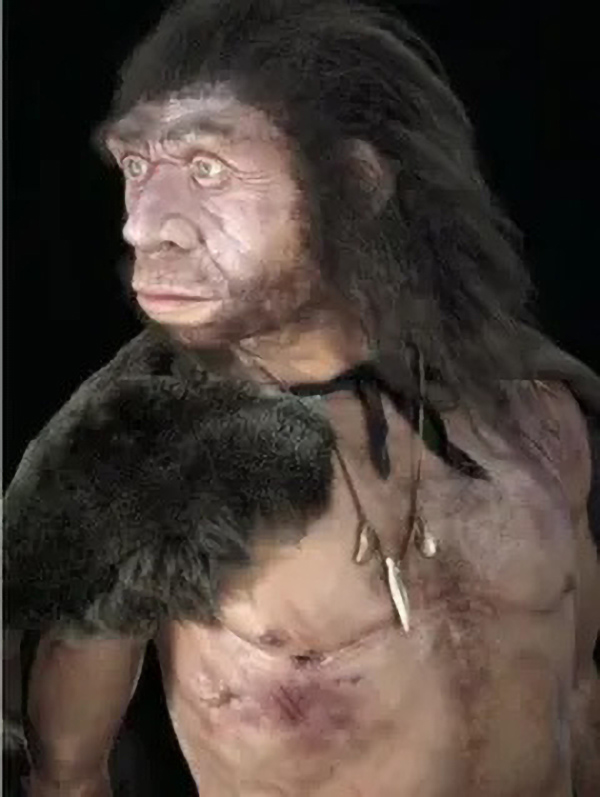

Stunning facial reconstructions of Hobbit, Neanderthal, and Homo Erectus bring human relatives to life Live Science - July 10, 2025

Four lifelike reconstructions of prehistoric humans have been unveiled - including a model of a species often dubbed "the hobbit," which, as an adult, was about the same height as a modern 4-year-old. The 3D models are featured in the upcoming five-part documentary series "Human," which explores the extraordinary story of human evolution over the past 300,000 years, from our rise in Africa, to our migration into Eurasia and across the globe, including to our journey through the Americas after going along the Bering Land Bridge during the last ice age.

125,000-year-old 'fat eating factory' run by Neanderthals discovered in Germany Live Science - July 3, 2025

An analysis of ancient animal bones found in Germany suggests that Neanderthals extracted grease from them to gobble up 125,000 years ago. These archaic human relatives had a process for extracting grease from animal bones - and it may have saved them from a lethal condition.

This May Be The World's Oldest Human Fingerprint, And That's Not All. Around 43,000 years ago, a Neanderthal dipped their finger in ocher and stamped the very center of a pebble. Science Alert - May 30, 2025

This one small marking on this one small stone still exists to this day. It was discovered in 2022 in the San Lázaro rock shelter of Central Spain, and it may be the world's oldest complete human fingerprint. More than that, it could also be one of the oldest known artistic representations of a human face.

Compelling evidence that Neanderthal and Homo sapiens engaged in cultural exchange PhysOrg - March 11, 2025

The first-ever published research on Tinshemet Cave reveals that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in the mid-Middle Paleolithic Levant not only coexisted but actively interacted, sharing technology, lifestyles, and burial customs. These interactions fostered cultural exchange, social complexity, and behavioral innovations, such as formal burial practices and the symbolic use of ocher for decoration.

Neanderthals, modern humans and a mysterious human lineage mingled in caves in ancient Israel, study finds Live Science - March 13, 2025

Fossil collection found in Neanderthal cave suggests abstract thinking PhysOrg - November 20, 2024

60,000-Year-Old Glue-Making Oven Found In Neanderthals' Seaside Cave IFL Science - November 20, 2024

Were Neanderthals Even More "Human" Than Us? IFL Science - October 1, 2024

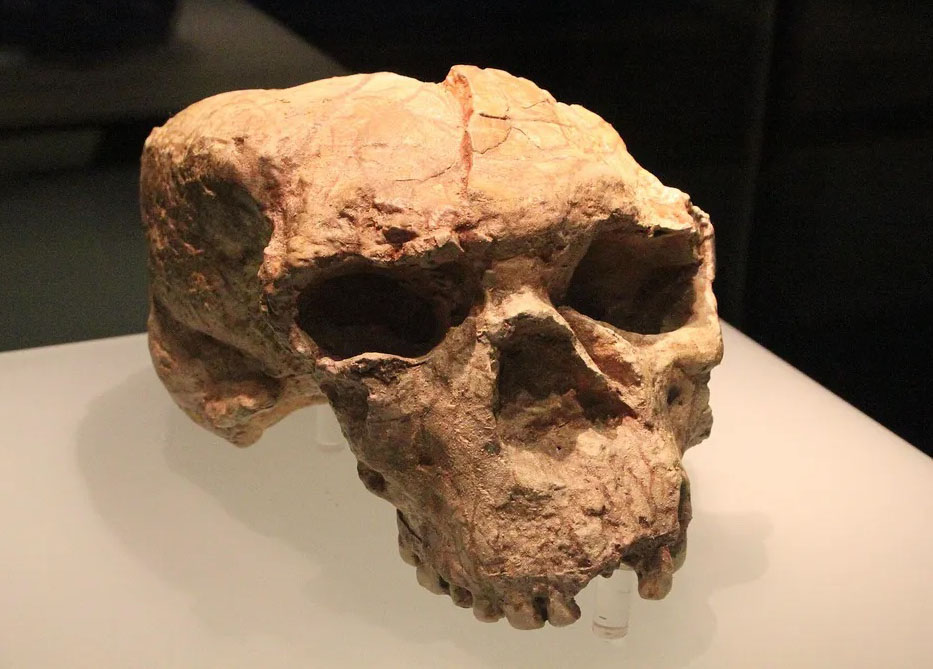

Ever since their discovery in the 19th century, Neanderthals have been unfairly tarnished as the heavy-browed, brutish cousins of Homo sapiens (whose name, by comparison, means "thinking man" in Latin). While the stereotype has been tough to shake, a huge amount of research has helped to reinvent the image of Neanderthals in the 21st century; just like us, they were highly intelligent, culturally complex, and emotionally sensitive beings.

DNA of 'Thorin,' one of the last Neanderthals, finally sequenced, revealing inbreeding and 50,000 years of genetic isolation Live Science - September 11, 2024

"Thorin", one of the last Neanderthals to walk the planet, was part of a previously unknown lineage that was isolated for 50,000 years, a new analysis of his DNA finds. Discovered in 2015 at the entrance to the Grotte Mandrin rock shelter in the Rhone River valley of southern France, Thorin - nicknamed after a dwarf in J. R. R. Tolkien's "The Hobbit" - has sometimes been called the "last Neanderthal" because he may have lived as recently as 42,000 years ago, close to when our closest human relatives disappeared. Although only his teeth and portions of the skull have been recovered so far, Thorin's genome was analyzed to better understand when and how Neanderthals disappeared.

Meet Thorin: A Cave-Dwelling Population Of Neanderthals Were Isolated For 50,000 Years IFL Science - September 11, 2024

A fossilized Neanderthal skeleton unearthed in France may have belonged to a previously undescribed lineage that split from other Neanderthals around 100,000 years ago. Just like modern humans, it looks like Neanderthals were a diverse and varied bunch. The remains were discovered in 2015 within a cave system of France’s Rhone Valley that was known to be home to early Homo sapiens. However, this latest work shows the cavern also housed Neanderthals at a different point in time, around 40,000 to 45,000 years ago, towards the end of their existence as a species. Upon sequencing its full genome, the researchers realized this wasn’t like any other Neanderthal found before.

First Ever 50,000-Year-Old Neanderthal Bone Spear Point Shows They Were "Flexible" Crafters IFL Science - September 11, 2024

Archaeologists have found an extremely unusual Neanderthal artefact at an excavation site in Spain, which is forcing them to rethink what we know of these extinct humans and their technologies. The researchers found the only known example of a horse bone spearhead, which shows that these ancient hominins could make hunting weapons out of such materials.

What Food Did Neanderthals Eat To Survive In The Ice Age? IFL Science - September 11, 2024

Neanderthals emerged in Eurasia as far back as 400,000 years ago, long before Homo sapiens arrived, and lived until around 40,000 years ago. Neanderthals and other prehistoric humans have a reputation for being bloodthirsty brutes, existing on a diet of megafauna meat and the flesh of their enemies. But it wasn’t just flame-grilled scraps of mammoth on the menu. A wealth of evidence shows that Neanderthals had a taste for meat, but also understood the value of fine seafood and even vegetarian fare. Some populations, in fact, ate an entirely plant-based diet.

Surprising Signs of Neanderthal Adaptability Discovered in Ancient Rock Shelter Science Alert - August 14, 2024

On an ordinary morning long ago, at the foothills of what are now the Pyrenees of Spain's Iberian Peninsula, a group of Neanderthals woke, greeted the day, and set about their tasks in the growing light. They could not have known that, tens of thousands of years later, modern humans scurrying about in the dirt would find traces of their existence, and be able to reconstruct details about how they lived their lives. That, however, is exactly what archaeologists have now done - discovering that Neanderthals were far more resilient than we suspected.

Neanderthals didn't truly go extinct, but were rather absorbed into the modern human population, DNA study suggests Live Science - July 11, 2024

A new study finds modern human DNA may have made up 2.5% to 3.7% of the Neanderthal genome. Neanderthals were among the closest extinct relatives of modern humans, with our lineages diverging around 500,000 years ago. More than a decade ago, scientists revealed that Neanderthals interbred with the ancestors of modern humans who journeyed out of Africa. Today, the genomes of modern human groups outside Africa contain about 1% to 2% of Neanderthal DNA.

Neanderthal DNA Exists in Humans, But One Piece Is Mysteriously Missing the Y sex chromosome, which is responsible for making males Science Alert - June 17, 2024

So what happened to the Neanderthal Y chromosome? It could have been lost by accident, or because of mating patterns or inferior function. However, the answer may lie in a century-old theory about the health of interspecies hybrids

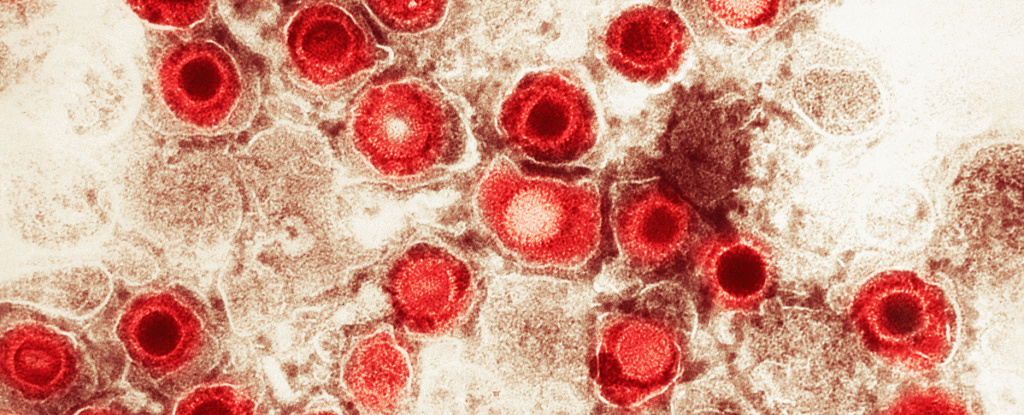

Oldest Known Human Viruses Found in 50,000-Year-Old Neanderthal Bones Science Alert - May 23, 2024

How Neanderthals went extinct while humans survived is one of the biggest questions in our species' history. Researchers have long wondered if our closest extinct relatives might have succumbed to viral infections that plague modern humans today. It is likely a combination of factors, along with other unknown factors, contributed to the eventual disappearance of Neanderthals

50,000-year-old Neanderthal bones harbor oldest-known human viruses Live Science - May 22, 2024

Neanderthals who lived 50,000 years ago were infected with three viruses that still affect modern humans today, researchers have discovered. These traces of ancient viruses are the oldest remnants of human viruses ever discovered, New Scientist reported. They are around 20,000 years older than the previous record-holder for the most ancient human virus ever found: a common-cold virus uncovered inside a pair of 31,000-year-old baby teeth in Siberia.

Scientists found the ancient viruses after sifting through DNA sequences drawn from the skeletons of two male Neanderthals originally found in the Chagyrskaya cave, located in the Altai mountains in Russia. Several sequences appeared to be viral in origin, so the team compared them to modern viruses known to cause lifelong infections. They ruled out the possibility that the viruses came from modern humans who handled the skeletons or by predators that fed on them by looking at specific signatures in the viral DNA that differed between the ancient and modern samples.

We Now Know Exactly When Humans And Neanderthals Hooked Up IFL Science - May 22, 2024

Despite disappearing around 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals continue to live on in the DNA of most modern humans. The persistence of these ancient genes indicates that our distant ancestors had a thing for stocky, big-nosed hominids, and new research has revealed exactly how these interspecies sexy times played out. It's estimated that between 1 and 4 percent of the genomes of all non-African humans alive today come from Neanderthals. These genes have helped to shape our appearance and behavior, although until now researchers had struggled to recreate the encounters that resulted in this exchange of genetic material.

'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors Live Science - May 17, 2024

Neanderthals and humans interbred at several points in our evolutionary history. The traces of these ancient interactions linger in our genes today. Neanderthals and humans mated millennia ago, and their legacy lives on in us today. Here's how. The group had traveled for thousands of miles, crossing Africa and the Middle East until finally reaching the dimly lit forests of the new continent. They were long-vanished members of our modern human tribe, and among the first Homo sapiens to enter Europe. There, these people would likely have encountered their distant cousins: Neanderthals. These small bands of modern-human relatives had hooded brows, large heads and squat bodies, and they had spent epochs acclimating to Europe's colder climate. At several points across millennia, these two forms of humanity would meet, mingle and mate. Tens of thousands of years later, these ancient encounters have left traces in the genetic code of billions of humans alive today. The lingering genes affect us in ways large and small, from our appearance to our risk of disease.

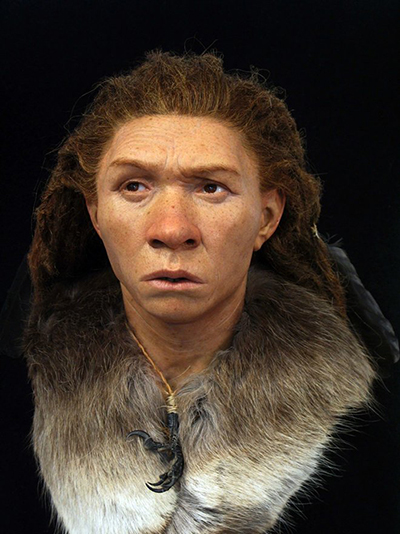

Face of 75,000-year-old Neanderthal woman revealed BBC - May 2, 2024

Scientists have produced a remarkable reconstruction of what a Neanderthal woman would have looked like when she was alive. It is based on the flattened, shattered remains of a skull whose bones were so soft when excavated they had the consistency of "a well-dunked biscuit". Researchers first had to strengthen the fragments before reassembling them. Expert paleoartists then created the 3D model.

What Was Life Like For Female Neanderthals? IFL Science - February 21, 2024

A type of complex adhesive found on stone tools made by Neanderthals has provided researchers with new insights into the intelligence of this extinct human species. Made of a mix of bitumen and ocher, the multi-compound glue resembles that employed by early Homo sapiens in Africa, indicating that our ancient cousins may have had a similar level of cognition to our own ancestors.

What Was Life Like For Female Neanderthals? IFL Science - February 20, 2024

If someone says “Neanderthal” to you, what’s the first thing that pops up in your head? If it happens to be an image of a “caveman”-esque person, it wouldn’t be all that surprising. A quick image search brings up results mostly showing male Neanderthals – but what about the females of the species? What do we know about them and how they lived?

Momentous Discovery Shows Neanderthals Could Produce Human-Like Speech Science Alert - November 23, 2023

ur Neanderthal cousins had the capacity to both hear and produce the speech sounds of modern humans, a study published in 2021 found. Based on a detailed analysis and digital reconstruction of the structure of the bones in their skulls, the study settled one aspect of a decades-long debate over the linguistic capabilities of Neanderthals.

Humans and Neanderthals mated 250,000 years ago, much earlier than thought Live Science - October 24, 2023

We carry DNA from extinct cousins like Neanderthals. Science is now revealing their genetic legacy PhysOrg - September 25, 2023

These ancient human cousins, and others called Denisovans, once lived alongside our early Homo sapiens ancestors. They mingled and had children. So some of who they were never went away - it's in our genes. And science is starting to reveal just how much that shapes us. Using the new and rapidly improving ability to piece together fragments of ancient DNA, scientists are finding that traits inherited from our ancient cousins are still with us now, affecting our fertility, our immune systems, even how our bodies handled the COVID-19 virus.

Reconstruction of the face of the oldest Neanderthal found in the Netherlands, nicknamed Krijn Live Science - August 20, 2023

Neanderthals are an extinct lineage of hominins that emerged around 400,000 years ago and died off around 40,000 years ago. They are the closest known human relatives and interbred with Homo sapiens.

The puzzle of Neanderthal aesthetics BBC - May 1, 2023

Sometime between 135,000-50,000 years ago, hands slick with animal blood carried more than 35 huge horned heads into a small, dark, winding cave. Tiny fires were lit amidst a boulder-jumbled floor, and the flame-illuminated chamber echoed to dull pounding, cracking and squelching sounds as the skulls of bison, wild cattle, red deer and rhinoceros were smashed open.

Ancient DNA Reveals the First Known Neanderthal Family who lived with a small community in a Siberian cave some 54,000 years ago Smithsonian - October 21, 2022

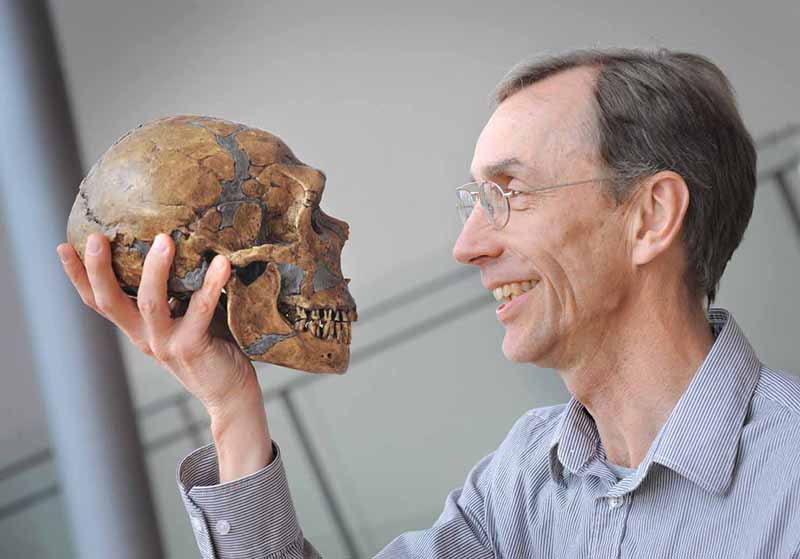

For the first time, researchers have identified a Neanderthal family: a father and his teenage daughter, as well as several others who were close relatives. They lived in Siberian caves around 54,000 years ago. A team of scientists, which included Svante Paabo, winner of this year’s Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, published the findings in Nature this week.

Ancient DNA gives rare snapshot of Neanderthal family ties. A new study suggests Neanderthals formed small, tight knit communities where females may have traveled to move in with their mates AP - October 19, 2022

The research used genetic sleuthing to offer a rare snapshot of Neanderthal family dynamics including a father and his teenage daughter who lived together in Siberia more than 50,000 years ago.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has gone to Sweden's Svante Paabo for his work on human evolution BBC - October 3, 2022

The Prize committee said he achieved the seemingly impossible task of cracking the genetic code of one of our extinct relatives - Neanderthals. He also performed the "sensational" feat of discovering the previously unknown relative - Denisovans.

His work helped explore our own evolutionary history and how humans spread around the planet. The Swedish geneticist's work gets to the heart of some of the most fundamental questions - where do we come from and what allowed us, Homo sapiens, to succeed while our relatives went extinct.

Swedish geneticist Svante Paabo wins Nobel Prize for medicine after sequencing first Neanderthal genome and discovered that Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals CNN - October 3, 2022

The Nobel Committee said Monday that Paabo accomplished something seemingly impossible when he sequenced the first Neanderthal genome and revealed that Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals. His discovery was made public in 2010, after Paabo pioneered methods to extract, sequence and analyze ancient DNA from Neanderthal bones. Thanks to his work, scientists can compare Neanderthal genomes with the genetic records of humans living today.

Like some people who research their ancestry I discovered this in reference to a connection with Neanderthals.

What does it mean if you have neanderthal dna?

Neanderthals died out 40,000 years ago, but there has never been more of their DNA on Earth The Conversation - September 1, 2022

Neanderthals have served as a reflection of our own humanity since they were first discovered in 1856. What we think we know about them has been shaped and moulded to fit our cultural trends, social norms and scientific standards. They have changed from diseased specimens to primitive sub-human lumbering cousins to advanced humans. We now know Homo neanderthalensis were very similar to ourselves and we even met them and frequently interbred. But why did they go extinct, while we survived, flourished and ended up taking over the planet?

Neanderthals changed ecosystems 125,000 years ago PhysOrg - December 16, 2021

Hunter-gathers caused ecosystems to change 125,000 years ago. Neanderthals used fire to keep the landscape open and thus had a big impact on their local environment.

Ancient case of disease spillover discovered in Neanderthal man who got sick butchering raw meat CNN - November 25, 2021

Scientists studying ancient disease have uncovered one of the earliest examples of spillover - when a disease jumps from an animal to a human - and it happened to a Neanderthal man who likely got sick butchering or cooking raw meat. Researchers were reexamining the fossilized bones of a Neanderthal who was found in a cave near the French village of La Chapelle-aux-Saints in 1908. The "Old Man of La Chapelle," as he became known, was the first relatively complete Neanderthal skeleton to be unearthed and is one of the best studied.

More than a century after his discovery, his bones are still yielding new information about the lives of Neanderthals, the heavily built Stone Age hominins that lived in Europe and parts of Asia before disappearing about 40,000 years ago.

Preserved baby Neanderthal milk tooth shows earlier emergence than in humans PhysOrg - November 25, 2021

In modern humans, deciduous teeth, also known as baby teeth, or milk teeth, generally emerge from the gums around seven to 10 months of age. They remain in place for approximately six years, when they are replaced by succedaneous or permanent dentition. Prior research has shown that the enamel that covers milk teeth has neonatal lines that mark the point where enamel was produced before and after a baby is born. Prior research has also shown that enamel grows on teeth in a daily cycle, which gives them cross-striations. The amount of tooth growth in a single day can be seen in the distance between the stripes. In this new effort, the researchers used this information as they studied a Neanderthal milk tooth from a child who lived approximately 120,000 near what is now the city of Krapina in Croatia.

Archaeologists discover remains of 9 Neanderthals near Rome PhysOrg - May 9, 2021

Italian archaeologists have uncovered the fossilized remains of nine Neanderthals in a cave near Rome, shedding new light on how the Italian peninsula was populated and under what environmental conditions. It confirmed that the Guattari Cave in San Felice Circeo was "one of the most significant places in the world for the history of Neanderthals." A Neanderthal skull was discovered in the cave in 1939. The fossilized bones include skulls, skull fragments, two teeth and other bone fragments. The oldest remains date from between 100,000 and 90,000 years ago, while the other eight Neanderthals are believed to date from 50,000-68,000 years ago, the Culture Ministry said in a statement.

Neanderthals had the capacity to perceive and produce human speech Science Alert - March 1, 2021

Neanderthals - the closest ancestor to modern humans - possessed the ability to perceive and produce human speech.

DNA from an ancient, unidentified ancestor was passed down to humans living today PhysOrg - August 6, 2020

A new analysis of ancient genomes suggests that different branches of the human family tree interbred multiple times, and that some humans carry DNA from an archaic, unknown ancestor. Roughly 50,000 years ago, a group of humans migrated out of Africa and interbred with Neanderthals in Eurasia. But that's not the only time that our ancient human ancestors and their relatives swapped DNA.

The sequencing of genomes from Neanderthals and a less well-known ancient group, the Denisovans, has yielded many new insights into these interbreeding events and into the movement of ancient human populations. In the new paper, the researchers developed an algorithm for analyzing genomes that can identify segments of DNA that came from other species, even if that gene flow occurred thousands of years ago and came from an unknown source. They used the algorithm to look at genomes from two Neanderthals, a Denisovan and two African humans. The researchers found evidence that 3 percent of the Neanderthal genome came from ancient humans, and estimate that the interbreeding occurred between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago. Furthermore, 1 percent of the Denisovan genome likely came from an unknown and more distant relative, possibly Homo erectus, and about 15% of these "super-archaic" regions may have been passed down to modern humans who are alive today.

The new findings confirm previously reported cases of gene flow between ancient humans and their relatives, and also point to new instances of interbreeding. Given the number of these events, the researchers say that genetic exchange was likely whenever two groups overlapped in time and space. Their new algorithm solves the challenging problem of identifying tiny remnants of gene flow that occurred hundreds of thousands of years ago, when only a handful of ancient genomes are available. This algorithm may also be useful for studying gene flow in other species where interbreeding occurred, such as in wolves and dogs.

Beach-combing Neanderthals dove for shells BBC - January 15, 2020

New data suggests that our evolutionary cousins the Neanderthals may have been diving under the ocean for clams. It adds to mounting evidence that the old picture of these ancient people as brutish and unimaginative is wrong. Until now, there had been little clear evidence that Neanderthals were swimmers. But a team of researchers who analyzed shells from a cave in Italy said that some must have been gathered from the seafloor by Neanderthals.

The Teeth of Early Neanderthals May Indicate the Species' Lineage Is Older Than Thought Smithsonian - May 16, 2019

Some of the oldest known Neanderthal remains include teeth that could push back the split with modern human lineages, but not all scientists are convinced.

Tooth of an adult Neanderthal found in France reveals the woman's diet was mostly made up of meat not plants Daily Mail - March 22, 2019

Neanderthals did NOT have hunched backs: New study on ancient spine of older male individual discovered in France shows their posture was much like modern humans' Daily Mail - February 25, 2019

Throughout the decades, our understanding of the Neanderthal's stature has varied dramatically; while early reconstructions suggested the ancestor stood with a hunch, others have imagined their spines as straighter than the modern human's. But, more recent research has indicated that their spinal curvature may actually have been a lot like our own.

Artificial Intelligence Study of Human Genome Finds Unknown Human Ancestor Smithsonian - February 9, 2019

<0>

The genetic footprint of a 'ghost population' may match that of a Neanderthal and Denisovan hybrid fossil found in Siberia

Faces Re-Created of Ancient Europeans, Including Neanderthal Woman and Cro-Magnon Man Live Science - January 29, 2019

About 5,600 years ago, a 20-year-old woman was buried with a tiny baby resting on her chest, a sad clue that she likely died in childbirth during the Neolithic. This woman and six other ancient Europeans - including a Cro-Magnon man, a Neanderthal woman and a man-bun-sporting dude from 250 B.C. - are on display at a museum in Brighton, England, now that a forensic artist has re-created their faces. These re-creations took hundreds of hours of work and are based on every available detail scientists could glean from these people's remains, including radiocarbon dating; the collection of dental plaque; and, when possible, the analysis of ancient DNA that detailed each person's eye, skin and hair color. This exhibit aims to shine a light on the past inhabitants of Brighton and mainland Europe by featuring hyper-realistic portrayals of their faces

Neanderthals and Denisovans Lived (and Mated) in This Siberian Cave Live Science - January 31, 2019

The Neanderthals and Denisovans - both relatives of modern humans - were roommates, literally, for thousands of years in a remote Siberian cave, two new studies find. Back in ancient times, this cave would have been a real estate agent's paradise; it's the only place in the world that Neanderthals, Denisovans and possibly even modern humans lived in together throughout history, the researchers found. The cave was so popular that hominins (a group that includes humans, our ancestors and our close evolutionary cousins like chimps) lived there almost continuously over both warm and cold periods during the past 300,000 years, the researchers found.

Neanderthals 'could kill at a distance' BBC - January 25, 2019

Neanderthals may once have been considered to be our inferior, brutish cousins, but a new study is the latest to suggest they were smarter than we thought - especially when it came to hunting. The research found that the now extinct species were creating weaponry advanced enough to kill at a distance. Scientists believe they crafted spears that could strike from up to 20m away.

Viewpoint: Why we still underestimate the Neanderthals PhysOrg - January 24, 2019

A paper out this week in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution reports the early arrival of modern humans to south-western Iberia around 44,000 years ago. Why should this be significant? It all has to do with the spread of our ancestors and the extinction of the Neanderthals. South-western Iberia has been claimed to have been a refuge of the Neanderthals, a place where they survived longer than elsewhere, but the evidence is disputed by some researchers. The latest paper, which is not about Neanderthals, has been taken by some as evidence of an arrival into this area which is much earlier than previously known. By implication, if modern humans were in south-western Iberia so early then they must have caused the early disappearance of the Neanderthals. It is a restatement of the idea that modern human superiority was the cause of the Neanderthal demise. Are these ideas tenable in the light of mounting genetic evidence that our ancestors interbred with the Neanderthals?

Neanderthals and Humans Were Hooking Up Way More Than Anyone Thought BBC - November 29, 2018

Way more sex happened between Neanderthals and the ancestors of modern humans across Europe and Asia than scientists originally thought, a new study finds. Scientists initially thought that interbreeding among the two groups was more isolated to a particular place and time - specifically, when they encountered each other in western Eurasia shortly after modern humans left Africa. This idea stemmed from the fact that the genomes of modern humans from outside Africa are only about 2 percent Neanderthal, on average. Subsequent research, however, has found that Neanderthal ancestry is 12 to 20 percent higher in modern East Asians compared to modern Europeans.

Reconstruction of a 60,000-year-old ribcage using 3D imaging reveals Neanderthals stood straighter than humans Daily Mail - October 30, 2018

Neanderthals were not hunched-over savages, according to a discovery that could radically alter our image of the ascent of man. Digital reconstruction of a Neanderthal's rib cage has revealed that the primitive hominid had a better posture than modern humans - as well as stronger lungs. Far from the knuckle-dragging beasts we thought them to be, the upright walking style of Neanderthals allowed them to walk far farther than Homo sapiens. This discovery has added more backing to the growing consensus that our ancient relatives were far more sophisticated than originally thought.

Inside the Siberian cave where a hybrid Neanderthal love child was found: Incredible photos show where the teenage daughter of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father lived 50,000 years ago Daily Mail - August 28, 2018

Stunning images reveal the inside of a Siberian cave where an amazing inter-species love child known as Denny lived more than 50,000 years ago. The remarkable girl, who was believed to be aged around 13, was not Homo sapiens. Instead, DNA analysis of a small fragment of bone has revealed she was the product of a sexual liaison between a Neanderthal mother and a father from another now-extinct early human grouping, known as the Denisovans. Other discoveries from the cave where Denny lived – which is found in the limestone foothills of the Altai Mountains – have proven the Denisovans were more advanced than both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.

Cave girl was half Neanderthal, half Denisovan BBC - August 22, 2018

Once upon a time, two early humans of different ancestry met at a cave in Russia. Some 50,000 years later, scientists have confirmed that they had a daughter together. DNA extracted from bone fragments found in the cave show the girl was the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. The discovery, reported in Nature, gives a rare insight into the lives of our closest ancient human relatives.

Neanderthals and Denisovans were humans like us, but belonged to different species.

Neanderthals and Denisovans Mated, New Hybrid Bone Reveals Live Science - August 22, 2018

The closest known extinct relatives of modern humans were the thick-browed Neanderthals and the mysterious Denisovans. Now, a bone fragment from a Siberian cave, perhaps from a teenage girl, has revealed the first known hybrid of these groups, a new study concludes. The finding confirms interbreeding that had been only hinted at in earlier genetic studies. A number of now-extinct human lineages not only lived alongside modern humans but even interbred with them, leaving traces of their DNA in the modern human genome. These lineages included the stocky Neanderthals, as well as the enigmatic Denisovans, known only from a few teeth and bones unearthed in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains. Archaeological excavations have revealed that Neanderthals and Denisovans coexisted in Eurasia, with Neanderthal bones ranging from 200,000 to 40,000 years old unearthed mostly in western Eurasia and Denisovans so far only known from fossils ranging from 200,000 to 30,000 years old found in eastern Eurasia. Prior work unearthed Neanderthal remains in Denisova Cave, raising questions on how closely they interacted.

Neanderthal mother, Denisovan father! Hybrid fossil - Newly-sequenced genome sheds light on interactions between ancient hominins Science Daily - August 22, 2018

Up until 40,000 years ago, at least two groups of hominins inhabited Eurasia -- Neanderthals in the west and Denisovans in the east. Now, researchers have sequenced the genome of an ancient hominin individual from Siberia, and discovered that she had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

Bite marks on ancient bear bones reveal Neanderthals hunted the huge predators and even stole their caves 50,000 years ago Daily Mail - April 17, 2018

Ancient Neanderthals may have ambushed bears twice the size of grizzlies to steal their caves, archaeologists have found. Researchers studying more than 1,700 prehistoric bear bones found evidence of cooking as well as bite marks that match Neanderthal teeth.A number of the bones show signs of blunt force trauma, perhaps inflicted as our heavy-browed ancestors attempted to extract the nutritious marrow inside.Archaeologists say the remains, which belonged to a total of 50 cave bears that lived 50,000 to 43,000 years ago, suggest Neanderthals waited until the predators drowsily awakened from hibernation before launching their attacks.

How Neanderthals influenced human genetics at the crossroads of Asia and Europe Science Daily - October 24, 2017

A new study explores the genetic legacy of ancient trysts between Neanderthals and the ancestors of modern humans, with a focus on Western Asia, the region where the first relations may have occurred. When the ancestors of modern humans migrated out of Africa, they passed through the Middle East and Turkey before heading deeper into Asia and Europe. Here, at this important crossroads, it's thought that they encountered and had sexual rendezvous with a different hominid species: the Neanderthals. Genomic evidence shows that this ancient interbreeding occurred, and Western Asia is the most likely spot where it happened. A new study explores the legacy of these interspecies trysts, with a focus on Western Asia, where the first relations may have occurred.

Older Neanderthal survived with a little help from his friends Science Daily - October 24, 2017

An older Neanderthal from about 50,000 years ago, who had suffered multiple injuries and other degenerations, became deaf and must have relied on the help of others to avoid prey and survive well into his 40s. More than his loss of a forearm, bad limp and other injuries, his deafness would have made him easy prey for the ubiquitous carnivores in his environment and dependent on other members of his social group for survival.

Video: Deformed and Elderly 50,000-Year-Old Skeleton Proves Neanderthals Cared About Each Other Newsweek - October 24, 2017

Deaf Neanderthals didn't stand much chance at survival unless they had friends, according to a new analysis of a skeleton discovered half a century ago in Iraq. Despite losing his hearing, some of his sight and part of his right arm, a Neanderthal referred to as Shanidar 1 managed to live until his 40s. That may not seem like a terribly long life, but living until 40 was pretty rare 50,000 years ago, when this man was alive.

Neanderthals dosed themselves with painkillers and possibly penicillin BBC - March 8, 2017

One sick Neanderthal chewed the bark of the poplar tree, which contains a chemical related to aspirin. He may also have been using penicillin, long before antibiotics were developed. The evidence comes from ancient DNA found in the dental tartar of Neanderthals living about 40,000 years ago in central Europe. Microbes and food stuck to the teeth of the ancient hominins gives scientists a window into the past. By sequencing DNA preserved in dental tartar, international researchers have found out new details of the diet, lifestyle and health of our closest extinct relatives.

Prehistoric 'Aspirin' Found in Sick Neanderthal's Teeth - National Geographic - March 8, 2017

Evidence of pain-killers is just one intriguing detail pulled from a closer look at the DNA in ancient tooth plaque. What looks to us like unsightly buildup has turned out to be a goldmine for microbiologists who study human evolution. Hardened plaque harvested from Neanderthals is loaded with genetic material from plants and animals these prehistoric hominins ate, as well as remnants of microbes that reveal a surprising amount about how they lived and even what made them sick.

Neanderthal middle ear structure found to be closer to modern human than apes PhysOrg - September 27, 2016

There has been a change in perception of Neanderthals in recent years as archaeologists have uncovered evidence that has suggested the extinct species of human was far more capable than has been conventionally believed. They built primitive homes, for example, created jewelry and painted on walls, and now, it appears they had an ear structure that would have enabled them to use vocal communications similar to modern humans. Prior research has suggested that Neanderthals came to exist approximately 280,000 years ago and lived in much of Europe and parts of Asia - but inexplicably disappeared approximately 40,000 years ago.

Body ornamentation among Neanderthals: Dig in France confirmed as Neanderthal remains Science Daily - September 20, 2016

Researchers have helped to solve an archaeological dispute -- confirming that Neanderthals were responsible for producing tools and artifacts previously argued by some to be exclusively in the realm of modern human cognitive abilities. Using ancient protein analysis, the team took part in an international research project to confirm the disputed origins of bone fragments in Chatelperron, France.

Neanderthals in Germany: First population peak, then sudden extinction Science Daily - July 21, 2016

Neanderthals once populated the entire European continent. Around 45,000 years ago, Homo neanderthalensis was the predominant human species in Europe. Archaeological findings show that there were also several settlements in Germany. However, the era of the Neanderthal came to an end quite suddenly. Based on an analysis of the known archaeological sites comes to the conclusion that Neanderthals reached their population peak right before their population rapidly declined and they eventually became extinct.

Inbred Neanderthals left humans a genetic burden PhysOrg - June 7, 2016

The Neanderthal genome included harmful mutations that made the hominids around 40% less reproductively fit than modern humans, according to estimates published in the latest issue of the journal Genetics. Non-African humans inherited some of this genetic burden when they interbred with Neanderthals, though much of it has been lost over time. The results suggest that these harmful gene variants continue to reduce the fitness of some populations today. The study also has implications for management of endangered species.

Neanderthals were stocky from birth PhysOrg - May 26, 2016

If a Neanderthal were to sit down next to us on the underground, we would probably first notice his receding forehead, prominent brow ridges and projecting, chinless face. Only on closer inspection would we notice his wider and thicker body. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig have now investigated whether the differences in physique between Neanderthals and modern humans are genetic or caused by differences in lifestyle. Their analysis of two well-preserved skeletons of Neanderthal neonates shows that Neanderthals' wide bodies and robust bones were formed by birth. The evolutionary lines of modern humans and Neanderthals diverged around 600,000 years ago.

Paleo-anthropologists know from bone finds that Neanderthals possessed not only a receding forehead, prominent brow ridges and projecting, chinless face, but also a different physique. They had more robust bones, a wider pelvis and shorter limbs. This may have been an evolutionary adaptation to the colder climate of Europe and Asia, as a more compact body loses less heat to the environment. However, the skeletal differences may also have arisen as a result of different lifestyles and activity patterns, because mechanical stresses affect the formation of bones.

DNA points to Neanderthal breeding barrier BBC - April 8, 2016

Incompatibilities in the DNA of Neanderthals and modern humans may have limited the impact of interbreeding between the two groups. It's now widely known that many modern humans carry up to 4% Neanderthal DNA. But a new analysis of the Neanderthal Y chromosome, the package of genes passed down from fathers to sons, shows it is missing from modern populations.

Modern men lack Y chromosome genes from Neanderthals Science Daily - April 7, 2016

Although it's widely known that modern humans carry traces of Neanderthal DNA, a new international study led by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine suggests that Neanderthal Y-chromosome genes disappeared from the human genome long ago.

How diet shaped human evolution Science Daily - March 30, 2016

Homo sapiens, the ancestor of modern humans, shared the planet with Neanderthals, a close, heavy-set relative that dwelled almost exclusively in Ice-Age Europe, until some 40,000 years ago. Black carbon image of hunting on sandstone. The Ice-Age diet -- a high-protein intake of large animals -- triggered physical changes in Neanderthals, namely a larger ribcage and a wider pelvis. Neanderthals were similar to Homo sapiens, with whom they sometimes mated -- but they were different, too. Among these many differences, Neanderthals were shorter and stockier, with wider pelvises and rib-cages than their modern human counterparts.

A world map of Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry in modern humans Science Daily - March 28, 2016

Most non-Africans possess at least a little bit Neanderthal DNA. But a new map of archaic ancestry suggests that many bloodlines around the world, particularly of South Asian descent, may actually be a bit more Denisovan, a mysterious population of hominids that lived around the same time as the Neanderthals. The analysis also proposes that modern humans interbred with Denisovans about 100 generations after their trysts with Neanderthals.

Do we owe our thick hair and tough skin to Neanderthals? Daily Mail - March 28, 2016

World map of prehistoric ancestry shows how interbreeding has changed and even helped modern humans. The study has unearthed some surprising new benefits these illicit encounters have gifted to modern humans living today.For example genetic variants inherited from Denisovans appear to have given some people in south Asia a better ability to detect subtle scents and helped others to survive at high altitudes.

400,000-year-old fossils from Spain provide earliest genetic evidence of Neanderthals Science Daily - March 16, 2016

Previous analyses of the hominins from Sima de los Huesos in 2013 showed that their maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA was distantly related to Denisovans, extinct relatives of Neanderthals in Asia. This was unexpected since their skeletal remains carry Neanderthals-derived features. Researchers have since worked on sequencing nuclear DNA from fossils from the cave, a challenging task as the extremely old DNA is degraded to very short fragments. The results now show that the Sima de los Huesos hominins were indeed early Neanderthals.

Neanderthals were wiped out because modern humans were more artistic - Cultural lifestyle gave us an edge and helped us innovate Daily Mail - February 1, 2015

Modern humans have been blamed for killing off the Neanderthals around 30,000 years ago by breeding with them and even murdering them. But now experts believe it was our ancestors' artistic and innovative abilities that ultimately led to the Neanderthal's demise. The experts believe our more advanced lifestyle gave us a cultural and competitive edge over our ancient cousins and this paved the way for their extinction.

Genetic analysis of 40,000-year-old jawbone reveals early modern humans interbred with Neanderthals PhysOrg - June 22, 2015

Neanderthals lived in Europe until about 35,000 years ago, disappearing at the same time modern humans were spreading across the continent. The new study provides the first genetic evidence that humans interbred with Neanderthals in Europe.

Analysis of bones found in Romania offer evidence of human and Neanderthal interbreeding in Europe PhysOrg - May 14, 2015

DNA testing of a human mandible fossil found in Romania has revealed a genome with 4.8 to 11.3 percent Neanderthal DNA - its original owner died approximately 40,000 years ago, Palaeogenomicist Qiaomei Fu reported to audience members at a Biology of Genomes meeting in New York last week. She noted also that she and her research team found long Neanderthal sequences. The high percentage suggests, she added, that the human had a Neanderthal in its family tree going back just four to six generations. The finding by the team provides strong evidence that humans and Neanderthals continued breeding in Europe, long after their initial co-mingling in the Middle East (after humans began migrating out of Africa.)

Fossil Teeth Suggest Humans Played Role in Neanderthal Extinction Live Science - April 23, 2015

Ancient teeth from Italy suggest that the arrival of modern humans in Western Europe coincided with the demise of Neanderthals there, researchers said. This finding suggests that modern humans may have caused Neanderthals to go extinct, either directly or indirectly, scientists added. Neanderthals are the closest extinct relatives of modern humans. Recent findings suggest that Neanderthals, who once lived in Europe and Asia, were closely enough related to humans to interbreed with the ancestors of modern humans - about 1.5 to 2.1 percent of the DNA of anyone outside Africa is Neanderthal in origin. Recent findings suggest that Neanderthals disappeared from Europe between about 41,000 and 39,000 years ago.

Neanderthal groups based part of their lifestyle on sexual division of labor Science Daily - February 19, 2015

Neanderthals divided some of their tasks according to their sex. A new study analyzed 99 teeth of 19 individuals from three different sites (El Sidron, in Asturias - Spain, L'Hortus in France, and Spy in Belgium), reveals that the dental grooves in the female fossils follow the same pattern, different to that found in male individuals.

Neanderthals disappeared from the Iberian Peninsula before than from the rest of Europe Science Daily - February 5, 2015

Until a few months ago different scientific articles dated the disappearance of the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) from Europe at around 40,000 years ago. However, a new study shows that these hominids could have disappeared before then in the Iberian Peninsula, closer to 45,000 years ago. In the Iberian Peninsula the Neanderthals may have disappeared 45,000 years ago.

DNA yields secrets of human pioneer BBC - October 22, 2014

DNA analysis of a 45,000-year-old human has helped scientists pinpoint when our ancestors interbred with Neanderthals. The genome sequence from a thigh bone found in Siberia shows the first episode of mixing occurred between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago. The male hunter is one of the earliest modern humans discovered in Eurasia. The study in Nature journal also supports the finding that our species emerged from Africa some 60,000 years ago, before spreading around the world. The analysis raises the possibility that the human line first emerged millions of years earlier than current estimates.

Neanderthals and Humans First Mated 50,000 Years Ago, DNA Reveals Live Science - October 22, 2014

The DNA from the 45,000-year-old bone of a man from Siberia is helping to pinpoint when modern humans and Neanderthals first interbred, researchers say. Although modern humans are the only surviving human lineage, others once lived on Earth. The closest extinct relatives of modern humans were the Neanderthals, who lived in Europe and Asiauntil they went extinct about 40,000 years ago. Recent findings revealed that Neanderthals interbred with ancestors of modern humans when modern humans began spreading out of Africa - 1.5 to 2.1 percent of the DNA of anyone living outside Africa today is Neanderthal in origin.

Neanderthal 'artwork' found in Gibraltar cave BBC - September 1, 2014

Mounting evidence suggests Neanderthals were not the brutes they were characterized as decades ago. But art, a high expression of abstract thought, was long considered to be the exclusive preserve of our own species. The scattered candidates for artistic expression by Neanderthals have not met with universal acceptance. However, the geometric pattern identified in Gibraltar, on the southern tip of Europe, was uncovered beneath undisturbed sediments that have also yielded Neanderthal tools.

New dates rewrite Neanderthal story BBC - August 20, 2014

Modern humans and Neanderthals co-existed in Europe 10 times longer than previously thought, a study suggests. The most comprehensive dating of Neanderthal bones and tools ever carried out suggests that the two species lived side-by-side for up to 5,000 years. The new evidence suggests that the two groups may even have exchanged ideas and culture, say the researchers.

Did Neanderthals eat their vegetables? PhysOrg - June 25, 2014

The popular conception of the Neanderthal as a club-wielding carnivore is, well, rather primitive, according to a new study conducted at MIT. Instead, our prehistoric cousin may have had a more varied diet that, while heavy on meat, also included plant tissues, such as tubers and nuts.

Skulls with mix of Neanderthal and primitive traits illuminate human evolution Science Daily - June 19, 2014

Researchers studying a collection of skulls in a Spanish cave identified both Neanderthal-derived features and features associated with more primitive humans in these bones. This "mosaic pattern" supports a theory of Neanderthal evolution that suggests Neanderthals developed their defining features separately, and at different times - not all at once. Having this new data from the Sima de los Huesos site, as the Spanish cave is called, has allowed scientists to better understand hominin evolution during the Middle Pleistocene, a period in which the path of hominin evolution has been controversial.

Talking Neanderthals challenge the origins of speech Science Daily - March 3, 2014

We humans like to think of ourselves as unique for many reasons, not least of which being our ability to communicate with words. But ground-breaking research shows that our 'misunderstood cousins,' the Neanderthals, may well have spoken in languages not dissimilar to the ones we use today. Pinpointing the origin and evolution of speech and human language is one of the longest running and most hotly debated topics in the scientific world. It has long been believed that other beings, including the Neanderthals with whom our ancestors shared Earth for thousands of years, simply lacked the necessary cognitive capacity and vocal hardware for speech.

Fifth of Neanderthals' genetic code lives on in modern humans The Guardian - January 29, 2014

Traces are lasting legacy of sexual encounters between our direct ancestors and Neanderthals from 65,000 years ago. The last of the Neanderthals may have died out tens of thousands of years ago, but large stretches of their genetic code live on in people today. Though many of us can claim only a handful of Neanderthal genes, when added together, the human population carries more than a fifth of the archaic human's DNA, researchers found. The finding means that scientists can study about 20% of the Neanderthal genome without having to prize the genetic material from fragile and ancient fossils. The Neanderthal traces in our genetic makeup are the lasting legacy of sexual encounters between our direct ancestors and the Neanderthals they met when they walked out of Africa and into Eurasia about 65,000 years ago.

Which parts of us are Neanderthal? Our genes point to skin and hair NBC - January 29, 2014

Researchers have found that Neanderthal genetic coding is found with high frequency in genes that affect skin characteristics. That suggests that beneficial coding was picked up from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to non-African environments. Earlier studies have suggested that the traits for redheadedness are of Neanderthal origin. A double-barreled comparison of ancient Neanderthal DNA with hundreds of modern-day genomes suggests that many of us have Neanderthal skin and hair traits - but other parts of the Neanderthal genome appear to have been bred out of us along the way.

Neanderthals gave us disease genes BBC - January 29, 2014

Genes that cause disease in people today were picked up through interbreeding with Neanderthals, a major study in Nature journal suggests. They passed on genes involved in type 2 diabetes, Crohn's disease and - curiously - smoking addiction. Genome studies reveal that our species (Homo sapiens) mated with Neanderthals after leaving Africa. But it was previously unclear what this Neanderthal DNA did and whether there were any implications for human health.

Diabetes risk gene 'from Neanderthals' BBC - December 26, 2013

A gene variant that seems to increase the risk of diabetes in Latin Americans appears to have been inherited from Neanderthals, a study suggests. We now know that modern humans interbred with a population of Neanderthals shortly after leaving Africa 60,000-70,000 years ago.

Neanderthals could speak like humans, study suggests BBC - December 20, 2013

An analysis of a Neanderthal's hyoid bone - a horseshoe shaped structure in the neck - suggests they had the ability to speak. Until now the strongest support came from a 1989 Neanderthal hyoid fossil, the same shape as those of humans. But computer modeling of how it works has shown their hyoid bone was also used in a very similar way.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS