The consistency paradox or grandfather paradox occurs when the past is changed in any way that directly negates the conditions required for the time travel to occur in the first place, thus creating a contradiction. A common example given is traveling to the past and intervening with the conception of one's ancestors (such as causing the death of the parent beforehand), thus affecting the conception of oneself.

If the time traveler were not born, then it would not be possible for the traveler to undertake such an act in the first place. Therefore, the ancestor lives to conceive the time-traveler's next-generation ancestor, and eventually the time traveler. There is thus no predicted outcome to this. Consistency paradoxes occur whenever changing the past is possible. A possible resolution is that a time traveller can do anything that did happen, but cannot do anything that did not happen. Doing something that did not happen results in a contradiction. This is referred to as the Novikov self-consistency principle. Read More ...

Physicist claims to have solved the infamous 'grandfather paradox,' making time travel (theoretically) possible Live Science - January 9, 2025

The grandfather paradox is just one of the thorny logical problems that arise with the concept of time travel. But one physicist says he has resolved them. Time travel has long been dismissed as impossible due in part to the infamous "grandfather paradox." This conundrum asks what would happen if someone traveled back in time and prevented their grandfather from having children, thus erasing the traveler's existence. However, a new study may have resolved this issue. By combining general relativity, quantum mechanics, and thermodynamics, the study demonstrates that time travel might be feasible without leading to these logical contradictions.

Time travel experiment demonstrates how to avoid the grandfather paradox PhysOrg - March 1, 2011

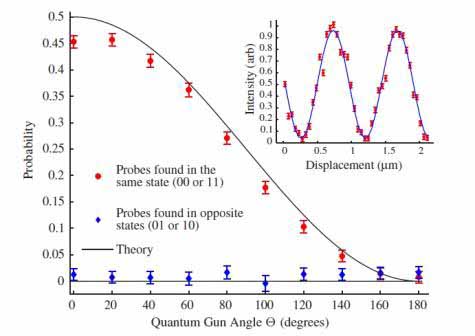

This graph shows that, as the accuracy of the quantum gun increases (from 0 to 180 degrees) so that it is more likely to flip a qubitÕs state, the probability of successful self-consistent teleportation (red dots) decreases. While the theoretical probability of teleportation of qubits in opposite states is zero, the experimental probability of qubits in opposite states (blue diamonds) is about 0.01.

The grandfather paradox is a proposed paradox of time travel first described (in this exact form) by the science fiction writer Rene Barjavel in his 1943 book "Le Voyageur Imprudent" ("The Imprudent Traveler)".

The paradox is this: suppose a man traveled back in time and killed his biological grandfather before the latter met the traveler's grandmother. As a result, one of the traveler's parents (and by extension the traveler himself) would never have been conceived. This would imply that he could not have traveled back in time after all, which means the grandfather would still be alive, and the traveler would have been conceived allowing him to travel back in time and kill his grandfather. Thus each possibility seems to imply its own negation, a type of logical paradox.

Despite the name, the grandfather paradox does not exclusively regard the impossibility of one's own birth. Rather, it regards any action that makes impossible the ability to travel back in time in the first place. The paradox's namesake example is merely the most commonly thought of when one considers the whole range of possible actions. Another example would be using scientific knowledge to invent a time machine, then going back in time and (whether through murder or otherwise) impeding a scientist's work that would eventually lead to the very information that you used to invent the time machine.

An equivalent paradox is known (in philosophy) as auto-infanticide, going back in time and killing oneself as a baby.

The grandfather paradox has been used to argue that backwards time travel must be impossible. However, a number of hypotheses have been postulated to avoid the paradox, such as the idea that the past is unchangeable, so the grandfather must have already survived the attempted killing; or the time traveler creates an alternate time line in which the traveler was born.

The Novikov self-consistency Principle and Kip S. Thorne expresses one view on how backwards time travel could be possible without a danger of paradoxes. According to this hypothesis, the only possible time lines are those entirely self-consistent - so anything a time traveler does in the past must have been part of history all along, and the time traveler can never do anything to prevent the trip back in time from happening, since this would represent an inconsistency. In layman's terms, this is often called determinism. It conflicts with the notion of free-will. Succinctly, this explanation states that if time travel is possible, then actions are determined by history.

There could be "an ensemble of parallel universes" such that when the traveller kills the grandfather, the act took place in (or resulted in the creation of) a parallel universe where the traveler's counterpart never exists as a result. However, his prior existence in the original universe is unaltered. Succinctly, this explanation states that: if time travel is possible, then multiple versions of the future exist in parallel universes. Alternate time lines would also apply if a person went back in time to shoot himself because in the past, he would be dead as in the future he would be alive and well.

Examples of parallel universes postulated in physics are:

M-theory is put forward as a hypothetical master theory that unifies the six superstring theories, although at present it is largely incomplete. One possible consequence of ideas drawn from M-theory is that multiple universes in the form of 3-dimensional membranes known as branes could exist side-by-side in a fourth large spatial dimension (which is distinct from the concept of time as a fourth dimension).

However, there is currently no argument from physics that there would be one brane for each physically possible version of history as in the many-worlds interpretation, nor is there any argument that time travel would take one to a different brane.

According to this theory, if one were to do something in the past that would cause their nonexistence, upon returning to the future, they would find themselves in a world where the effects (and chain reactions thereof) their actions are not present, as the person never existed. Through this theory, they would still exist, though. A famous example of this theory is It's A Wonderful Life.

The idea of preventing paradoxes by supposing that the time traveler is taken to a parallel universe while his original history remains intact, which is discussed above in the context of science, is also common in science fiction.

Another resolution, of which the Novikov self-consistency principle can be taken as an example, holds that if one were to travel back in time, the laws of nature (or other intervening cause) would simply forbid the traveler from doing anything that could later result in their time travel not occurring. For example, a shot fired at the traveler's grandfather misses, or the gun jams or misfires, or the grandfather is injured but not killed, or the person killed turns out to be not the real grandfather - or some other event prevents the attempt from succeeding. No action the traveler takes to affect change can ever succeed, as some form of "bad luck" or coincidence always prevents the outcome. In effect, the traveler cannot change history.

Often in fiction, the time traveler does not merely fail to prevent the actions, but in fact precipitate them, usually by accident. - Predestination Paradox

This theory might lead to concerns about the existence of free will (in this model, free will may be an illusion, or at least not unlimited). This theory also assumes that causality must be constant: i.e. that nothing can occur in the absence of cause, whereas some theories hold that an event may remain constant even if its initial cause was subsequently eliminated.

Closely related but distinct is the notion of the time line as self-healing. The time-traveller's actions are like throwing a stone in a large lake; the ripples spread, but are soon swamped by the effect of the existing waves. For instance, a time traveller could assassinate a politician who led his country into a disastrous war, but the politician's followers would then use his murder as a pretext for the war, and the emotional effect of that would cancel out the loss of the politician's charisma. Or the traveller could prevent a car crash from killing a loved one, only to have the loved one killed by a mugger, or fall down the stairs, choke on a meal, killed by a stray bullet, etc.

In the 2002 film The Time Machine, this scenario is shown where the main character builds a time machine to save his fiance from being killed by a mugger, only for her to die in a car crash instead; as he learns from a trip to the future, he cannot save her with the machine or he would never have been inspired to build the machine so that he could go back and save her in the first place.

In some stories it is only the event that precipitated the time traveler's decision to travel back in time that cannot be substantially changed, in others all attempted changes "heal" in this way, and in still others the universe can heal most changes but not sufficiently drastic ones. This is also the explanation advanced by the Doctor Who role-playing game, which supposes that Time is like a stream; you can dam it, divert it, or block it, but the overall direction resumes after a period of conflict.

It also may not be clear whether the time traveler altered the past or precipitated the future he remembers, such as a time traveler who goes back in time to persuade an artist - whose single surviving work is famous - to hide the rest of the works to protect them. If, on returning to his time, he finds that these works are now well-known, he knows he has changed the past.

On the other hand, he may return to a future exactly as he remembers, except that a week after his return, the works are found. Were they actually destroyed, as he believed when he traveled in time, and has he preserved them? Or was their disappearance occasioned by the artist's hiding them at his urging, and the skill with which they were hidden, and so the long time to find them, stemmed from his urgency?

Some science fiction stories suggest that any paradox would destroy the universe, or at least the parts of space and time affected by the paradox. The plots of such stories tend to revolve around preventing paradoxes, such as the final episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

A less destructive alternative of this theory suggests the death of the time traveller whether the history is altered or not; an example would be in the first part of the Back to the Future trilogy, where the lead character's alteration of history results in a risk of his own disappearance, and he has to fix the alteration to preserve his own existence. In this theory, killing one's grandfather would result in the disappearance of oneself, history would erase all traces of the person's existence, and the death of the grandfather would be caused by another means (say, another existing person firing the gun); thus, the paradox would never occur from a historical viewpoint.

This theory is partially similar to other theories on time travel. While stating that if time travel is possible it would be impossible to violate the grandfather paradox, it goes further to state that any action taken that itself negates the time travel event cannot occur. The consequences of such an event would in some way negate that event, be it by either voiding the memory of what one is doing before doing it, by preventing the action in some way, or even by destroying the universe among other possible consequences. It states therefore that to successfully change the past one must do so incidentally.

For example, if one tried to stop the murder of one's parents, he would fail. On the other hand, if one traveled back and did something to some random person that as a result prevented the death of someone else's parents, then such an event would be successful, because the reason for the journey and therefore the journey itself remains unchanged preventing a paradox.

In addition, if this event had some colossal change in the history of mankind, and such an event would not void the ability or purpose of the journey back, it would occur, and would hold. In such a case, the memory of the event would immediately be modified in the mind of the time traveler.

An example of this would be for someone to travel back to observe life in Austria in 1887 and while there shoot five people, one of which was one of Hitler's parents. Hitler would therefore never have existed, but since this would not prevent the invention of the means for time travel, or the purpose of the trip, then such a change would hold. But for it to hold, every element that influenced the trip must remain unchanged. This would void someone convincing another party to travel back to kill the people without knowing who they are and making the time line stick, because by being successful, they would void the first party's influence and therefore the second party's actions.

This issues is treated humorously in an episode of Futurama in which Fry travels back in time and inadvertently causes his grandfather's death before he marries his grandmother. His distraught grandmother then seduces him, and on returning to his own time, Fry learns that he is his own grandfather.