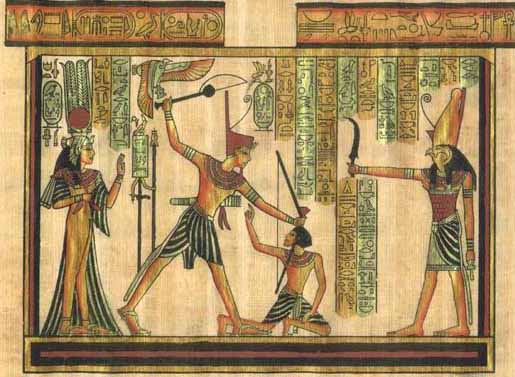

The origins of the unified Egyptian state are unclear, and there are no contemporary sources, and later sources are unclear and contradictory. Around 3100 BC a king unified the whole of the Nile Valley between the Delta and the First Cataract at Aswan, with the center of power in Memphis. Traditionally (according to Manetho), this king was known as Menes. This king may be identified as one the individuals known to historians as King Menes/Narmer.or Hor-Aha, or another person entirely.

The unified state seems to have arrived at the same time as the development of writing, the start of large scale construction and the venturing out from the Nile Valley to trade (or perhaps campaign) in Nubia and Syria/Palestine.

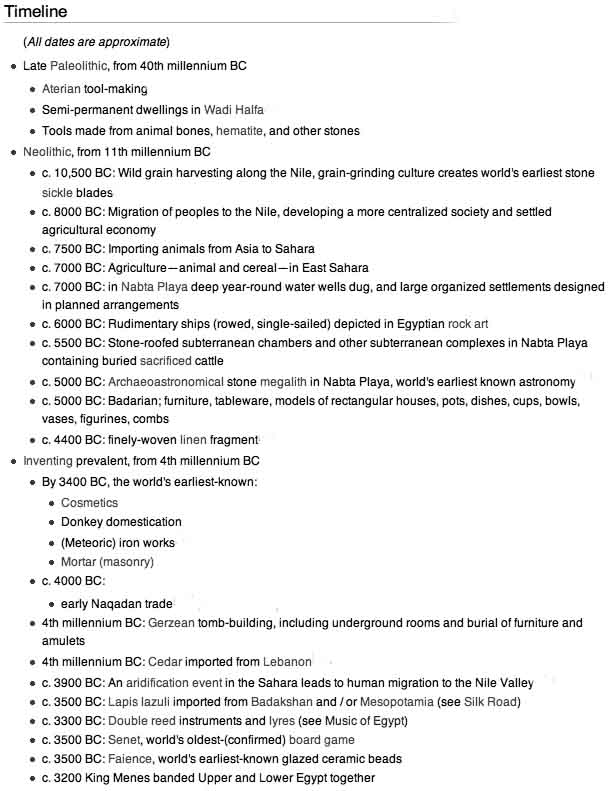

The Predynastic Period is traditionally equivalent to the Neolithic period, beginning ca. 6000 BC and including the Protodynastic Period (Naqada III).

The dates of the Predynastic period were first defined before widespread archaeological excavation of Egypt took place, and recent finds indicating very gradual Predynastic development have led to controversy over when exactly the Predynastic period ended. Thus, the term "Protodynastic period," sometimes called "Dynasty 0," has been used by scholars to name the part of the period which might be characterized as Predynastic by some and Early Dynastic by others.

The Predynastic period is generally divided into cultural periods, each named after the place where a certain type of Egyptian settlement was first discovered. However, the same gradual development that characterizes the Protodynastic period is present throughout the entire Predynastic period, and individual "cultures" must not be interpreted as separate entities but as largely subjective divisions used to facilitate study of the entire period.

The vast majority of Predynastic archaeological finds have been in Upper Egypt, because the silt of the Nile River was more heavily deposited at the Delta region, completely burying most Delta sites long before modern times.

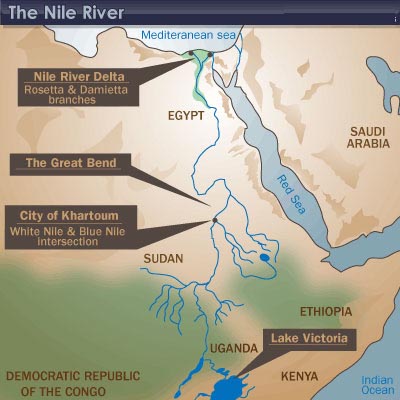

The Nile River is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa, generally regarded as the longest river in the world. It is 6,650 km (4,130 miles) long. It runs through the ten countries of Sudan, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Egypt.

The Nile has two major tributaries, the White Nile and Blue Nile. The White Nile is longer and rises in the Great Lakes region of central Africa, with the most distant source still undetermined but located in either Rwanda or Burundi. It flows north through Tanzania, Lake Victoria, Uganda and South Sudan. The Blue Nile is the source of most of the water and fertile soil. It begins at Lake Tana in Ethiopia and flows into Sudan from the southeast. The two rivers meet near the Sudanese capital of Khartoum.

The northern section of the river flows almost entirely through desert, from Sudan into Egypt, a country whose civilization has depended on the river since ancient times. Most of the population and cities of Egypt lie along those parts of the Nile valley north of Aswan, and nearly all the cultural and historical sites of Ancient Egypt are found along riverbanks. The Nile ends in a large delta that empties into the Mediterranean Sea.

The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that "Egypt was the gift of the Nile". An unending source of sustenance, it provided a crucial role in the development of Egyptian civilization. Silt deposits from the Nile made the surrounding land fertile because the river overflowed its banks annually. The Ancient Egyptians cultivated and traded wheat, flax, papyrus and other crops around the Nile. Wheat was a crucial crop in the famine-plagued Middle East. This trading system secured Egypt's diplomatic relationships with other countries, and contributed to economic stability.

Far-reaching trade has been carried on along the Nile since ancient times. The Ishango bone is probably an early tally stick. It has been suggested that this shows prime numbers and multiplication, but this is disputed. In the book "How Mathematics Happened: The First 50,000 Years", Peter Rudman argues that the development of the concept of prime numbers could only have come about after the concept of division, which he dates to after 10,000 BC, with prime numbers probably not being understood until about 500 BC. He also writes that "no attempt has been made to explain why a tally of something should exhibit multiples of two, prime numbers between 10 and 20, and some numbers that are almost multiples of 10." It was discovered along the headwaters of the Nile (near Lake Edward, in northeastern Congo) and was carbon-dated to 20,000 BC.

Water buffalo were introduced from Asia, and Assyrians introduced camels in the 7th century BC. These animals were killed for meat, and were domesticated and used for ploughing - or in the camel's case, carriage. Water was vital to both people and livestock. The Nile was also a convenient and efficient means of transportation for people and goods.

The Nile was an important part of ancient Egyptian spiritual life. Hapi was the god of the annual floods, and both he and the pharaoh were thought to control the flooding. The Nile was considered to be a causeway from life to death and the afterlife. The east was thought of as a place of birth and growth, and the west was considered the place of death, as the god Ra, the Sun, underwent birth, death, and resurrection each day as he crossed the sky. Thus, all tombs were west of the Nile, because the Egyptians believed that in order to enter the afterlife, they had to be buried on the side that symbolized death.

As the Nile was such an important factor in Egyptian life, the ancient calendar was even based on the 3 cycles of the Nile. These seasons, each consisting of four months of thirty days each, were called Akhet, Peret, and Shemu. Akhet, which means inundation, was the time of the year when the Nile flooded, leaving several layers of fertile soil behind, aiding in agricultural growth. Peret was the growing season, and Shemu, the last season, was the harvest season when there were no rains.

The Nile river, around which much of the population of the country clusters, has been the lifeline for Egyptian culture since nomadic hunter-gatherers began living along the Nile during the Pleistocene. Traces of these early peoples appear in the form of artifacts and rock carvings along the terraces of the Nile and in the oases. By about 6000 BC, organized agriculture and large building construction had appeared in the Nile Valley.

Between 5500 and 3100 BC, during Egypt's Predynastic Period, small settlements flourished along the Nile.

By the late Predynastic Period, just before the first Egyptian dynasty, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms, known as Upper and Lower Egypt. The dividing line was drawn roughly in the area of modern Cairo.

The Nile river (iteru in Ancient Egyptian) flows northward through the center of Egypt from a southerly point to the Mediterranean. The geologically lower delta region to the north, where the Nile river branches out into several mouths providing a wide, rich area of agricultural land, was known as Lower Egypt.

Whereas the geologically higher land upriver to the south, where the river valley is narrow and the fertile land on either side may only be a couple of miles in width, was known as Upper Egypt.

The two kingdoms were unified by Narmer in c. 3100 BC, and a series of dynasties ruled Egypt for the next three millenia. The last native dynasty, known as the Thirtieth Dynasty, fell to the Persians in 343 BC.

In ancient Egypt, the narrow strip of fertile land which runs alongside the Nile was called Kemet ("the black land", in Ancient Egyptian Kmt), a reference to the rich, black silt that is deposited there every year by the Nile floodwaters. The ancient Egyptians used this land for growing crops. It was the only land in ancient Egypt that could be farmed. In contrast, the barren desert that bordered the fertile land to the east and west was called Deshret ("the red land", in Ancient Egyptian Dsrt), c.f. Herodotus: "Egypt is a land of black soil. We know that Libya is a redder earth".

These deserts separated ancient Egypt from neighboring civilizations and provided a natural defense against invading armies. They also provided a source of precious metals and semi-precious stones. The vowels within the consonants K-M-T and D-S-R-T are not known with certainty. Coptic, however, provides some indication.

Egyptian society was a merging of North and Northeast African as well as Southwest Asian peoples. Modern genetics reveals that the Egyptian population today is characterized by paternal lineages common to North Africans primarily, and to some Near Eastern peoples. Studies based on the maternal lineages closely links modern Egyptians with people from modern Ethiopia. The ancient Egyptians themselves traced their origin to a land they called Punt, or "Ta Nteru" ("Land of the Gods"), which most Egyptologists locate in the area encompassing the Ethiopian Highlands.

A recent bioanthropological study on the dental morphology of ancient Egyptians confirms dental traits most characteristic of North African and to a lesser extent Southwest Asian populations. The study also establishes biological continuity from the predynastic to the post-pharaonic periods. Among the samples included is skeletal material from the Hawara tombs of Fayum, which was found to most closely resemble the Badarian series of the predynastic. A study based on stature and body proportions suggests that Nilotic or tropical body characteristics were also present in some later groups as the Egyptian empire expanded southward. Although analyzing the hair of ancient Egyptian mummies from the Late Middle Kingdom has revealed evidence of a stable diet, mummies from circa 3200 BC show signs of severe anemia and hemolitic disorders.

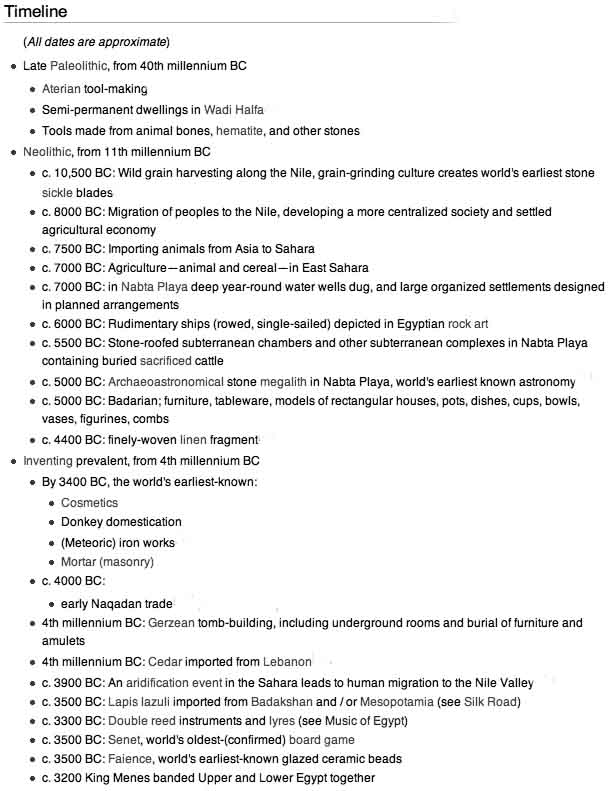

The Late Paleolithic in Egypt started around 30,000 BC. The Nazlet Khater skeleton was found in 1980 and dated in 1982 from nine samples ranging between 35,100 to 30,360 years. This specimen is the only complete modern human skeleton from the earliest Late Stone Age in Africa.

Some of the oldest known buildings were discovered in Egypt by archaeologist Waldemar Chmielewski along the southern border near Wadi Halfa. They were mobile structures - easily disassembled, moved, and reassembled - providing hunter-gatherers with semi-permanent habitation.

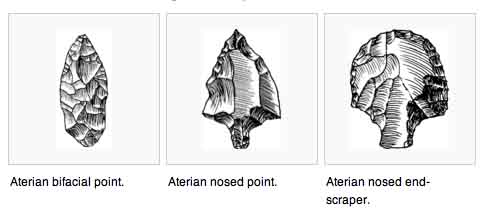

The Aterian industry is a name given by archaeologists to a type of stone tool manufacturing dating to the Middle Stone Age (or Middle Palaeolithic) derived from the Mousterian culture in the region around the Atlas Mountains and the northern Sahara, it refers the site of Bir el Ater, south of Annaba. The industry was probably created by modern humans (Homo sapiens), albeit of an early type, as shown by the few skeletal remains known so far from sites on the Moroccan Atlantic coast extending to Egypt.

Bifacially-worked leaf shaped and tanged projectile points are a common artifact type and so are racloirs and Levallois flakes. Items of personal adornment (pierced and ochred Nassarius shell beads) are known from at least one Aterian site, with an age of 82,000 years.

Aterian tool-making reached Egypt c. 40,000 BC.

The Khormusan culture in Egypt began between 40,000 and 30,000 BC. Khormusans developed advanced tools not only from stone but also from animal bones and hematite. They also developed small arrow heads resembling those of Native Americans, but no bows have been found. The end of the Khormusan came around 16,000 B.C. with the appearance of other cultures in the region, including the Gemaian.

The Halfan culture flourished along the Nile Valley of Egypt and Nubia between 18,000 and 15,000 BC, though one Halfan site dates to before 24,000 BC. They survived on a diet of large herd animals and the Khormusan tradition of fishing. Greater concentrations of artifacts indicate that they were not bound to seasonal wandering, but settled for longer periods. They are viewed as the parent culture of the Ibero-Maurusian industry, which spread across the Sahara and into Spain. The Halfan culture was derived in turn from the Khormusan, which depended on specialized hunting, fishing, and collecting techniques for survival. The primary material remains of this culture are stone tools, flakes, and a multitude of rock paintings.

About twenty archaeological sites in upper Nubia give evidence for the existence of a grain-grinding Mesolithic culture called the Qadan Culture, which practiced wild grain harvesting along the Nile during the beginning of the Sahaba Daru Nile phase, when desiccation in the Sahara caused residents of the Libyan oases to retreat into the Nile valley.

Qadan peoples developed sickles and grinding stones to aid in the collecting and processing of these plant foods prior to consumption. However there are no indications of the use of these tools after around 10,000 BC, when hunter-gathers replaced them.

In Egypt, analyses of pollen found at archaeological sites indicate that the Sebilian culture (also known as Esna culture) were gathering wheat and barley. Domesticated seeds were not found (modern wheat and barley originated in Asia Minor and Palestine). It has been hypothesized that the sedentary lifestyle used by farmers led to increased warfare, which was detrimental to farming and brought this period to an end.

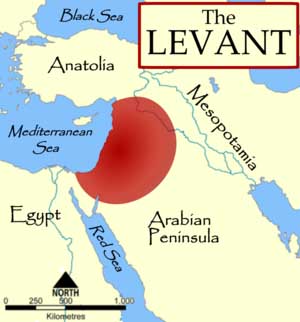

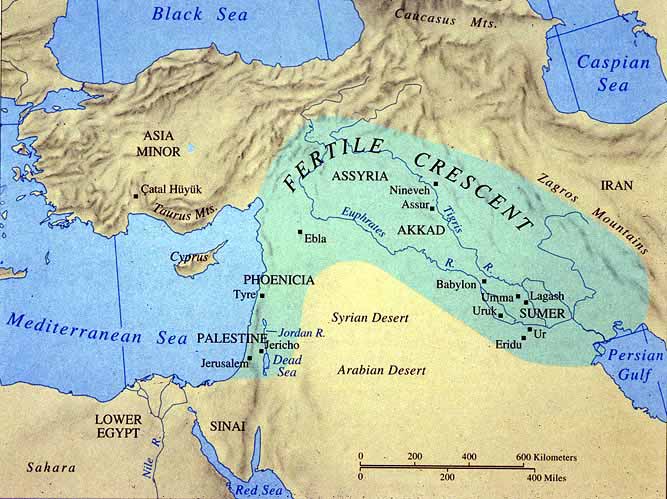

The Mushabian culture emerged from along the Nile Valley and is viewed as a parent of the Natufian culture, which is associated with early agriculture Epipalaeolithic Natufians carried parthenocarpic figs from Africa to the southwestern corner of the Fertile Crescent, c. 10,000 BC. The Mushabians are considered to have migrated to the Levant, merging with the Kebaran.

The Harifians are viewed as migrating out of the Fayyum and the Eastern Deserts of Egypt during the late Mesolithic to merge with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) culture, whose tool assemblage resembles that of the Harifian. This assimilation led to the Circum-Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, a group of cultures that invented nomadic pastoralism, and may have been the original culture which spread Proto-Semitic languages throughout Mesopotamia.

The Qadan culture was a culture that, archaeological evidence suggests, originated in Northeast Africa approximately 15,000 years ago. This way of life is estimated to have persisted for approximately 4,000 years, and was characterized by hunting, as well as a unique approach to food gathering that incorporated the preparation and consumption of wild grasses and grains.

In archaeological terms, this culture is generally viewed as a cluster of Mesolithic Stage communities living in Nubia in the upper Nile Valley prior to 9000 bc, at a time of relatively high water levels in the Nile, characterized by a diverse stone tool industry that is taken to represent increasing degrees of specialization and locally differentiated regional groupings There is some evidence of conflict between the groups. The Qadan economy was based on fishing, hunting, and, as mentioned, the extensive use of wild grain.

About twenty archaeological sites in upper Nubia give evidence for the existence of a grain-grinding Mesolithic culture called the Qadan Culture, which practiced wild grain harvesting along the Nile during the beginning of the Sahaba Daru Nile phase, when desiccation in the Sahara caused residents of the Libyan oases to retreat into the Nile valley.

Qadan peoples developed sickles and grinding stones to aid in the collecting and processing of these plant foods prior to consumption. However there are no indications of the use of these tools after around 10,000 BC, when hunter-gathers replaced them.

In Egypt, analyses of pollen found at archaeological sites indicate that the Sebilian culture (also known as Esna culture) were gathering wheat and barley. Domesticated seeds were not found (modern wheat and barley originated in Asia Minor and Palestine). It has been hypothesized that the sedentary lifestyle used by farmers led to increased warfare, which was detrimental to farming and brought this period to an end.

The Mushabian culture (alternately, Mushabi or Mushabaean) is suggested to have originated along the Nile Valley prior to migrating to the Levant, due to similar industries demonstrated among archaeological sites in both regions but with the Nile valley sites predating those found in the Sinai regions of the Levant.

Accordingly Bar-Yosef posits, "The population overflow from Northeast Africa played a definite role in the establishment of the Natufian adaptation, which in turn led to the emergence of agriculture as a new subsistence system."

The migration of farmers from the Middle East into Europe is believed to have significantly influenced the genetic profile of contemporary Europeans. The Natufian culture which existed about 12,000 years ago in the Levant, has been the subject of various archeological investigations as the Natufian culture is generally believed to be the source of the European and North African Neolithic.

The Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert were formidable barriers to gene flow between Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe. But Europe was periodically accessible to Africans due to fluctuations in the size and climate of the Sahara. At the Strait of Gibraltar, Africa and Europe are separated by only 15 km of water. At the Suez, Eurasia is connected to Africa forming a single land mass. The Nile river valley, which runs from East Africa to the Mediterranean Sea served as a bidirectional corridor in the Sahara desert, that frequently connected people from Sub-Saharan Africa with the peoples of Eurasia.

According to Bar-Yosef the Natufian culture emerged from the mixing of the Kebaran (already indigenous to the Levant) and the Mushabian (migrants into the Levant from North Africa). Modern analysis comparing 24 craniofacial measurements reveal a predominantly cosmopolitan population within the pre-Neolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age Fertile Crescent, supporting the view that a diverse population of peoples occupied this region during these time periods. In particular, evidence demonstrates the presence of North European, Central European, Saharan and some Sub-Saharan African presence within the region, especially among the Epipalaeolithic Natufians of Israel. These studies further argue that over time the Sub-Saharan influences would have been "diluted" out of the genetic picture due to interbreeding between Neolithic migrants from the Near East and indigenous hunter-gatherers whom they came in contact with.

The Harifians are viewed as migrating out of the Fayyum and the Eastern Deserts of Egypt during the late Mesolithic to merge with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) culture, whose tool assemblage resembles that of the Harifian. This assimilation led to the Circum-Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, a group of cultures that invented nomadic pastoralism, and may have been the original culture which spread Proto-Semitic languages throughout Mesopotamia.

Faiyum A culture

Continued desiccation forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently and adopt a more sedentary lifestyle.

The period from 9000 to 6000 BC has left very little in the way of archaeological evidence. Around 6000 BC, Neolithic settlements appear all over Egypt. Studies based on morphological, genetic, and archaeological data have attributed these settlements to migrants from the Fertile Crescent returning during the Egyptian and North African Neolithic, possibly bringing agriculture to the region.

However, other regions in Africa independently developed agriculture at about the same time: the Ethiopian highlands, the Sahel, and West Africa. Moreover, some morphological and post-cranial data has linked the earliest farming populations at Fayum, Merimde, and El-Badari, to local North African Nile populations. The archaeological data suggests that Near Eastern domesticates were incorporated into a pre-existing foraging strategy and only slowly developed into a full-blown lifestyle, contrary to what would be expected from settler colonists from the Near East. Finally, the names for the Near Eastern domesticates imported into Egypt were not Sumerian or Proto-Semitic loan words, which further diminishes the likelihood of a mass immigrant colonization of lower Egypt during the transition to agriculture.

Weaving is evidenced for the first time during the Faiyum A Period. People of this period, unlike later Egyptians, buried their dead very close to, and sometimes inside, their settlements.

Although archaeological sites reveal very little about this time, an examination of the many Egyptian words for "city" provide a hypothetical list of reasons why the Egyptians settled. In Upper Egypt, terminology indicates trade, protection of livestock, high ground for flood refuge, and sacred sites for deities.

From about 5000 to 4200 BC the Merimde culture, so far only known from a big settlement site at the edge of the Western Delta, flourished in Lower Egypt. The culture has strong connections to the Faiyum A culture as well as the Levant. People lived in small huts, produced a simple undecorated pottery and had stone tools. Cattle, sheep, goats and pigs were held. Wheat, sorghum and barley were planted. The Merimde people buried their dead within the settlement and produced clay figurines. The first Egyptian lifesize head made of clay comes from Merimde.

The El Omari culture is known from a small settlement near modern Cairo. People seem to have lived in huts, but only postholes and pits survive. The pottery is undecorated. Stone tools include small flakes, axes and sickles. Metal was not yet known. Their sites were occupied from 4000 BC to the Archaic Period.

The Maadi culture (also called Buto Maadi culture) is the most important Lower Egyptian prehistoric culture contemporary with Naqada I and II phases in Upper Egypt. The culture is best known from the site Maadi near Cairo, but is also attested in many other places in the Delta to the Fayum region.

Copper was known, and some copper adzes have been found. The pottery is simple and undecorated and shows, in some forms, strong connections to Southern Israel. People lived in small huts, partly dug into the ground. The dead were buried in cemeteries, but with few burial goods. The Maadi culture was replaced by the Naqada III culture; whether this happened by conquest or infiltration is still an open question.

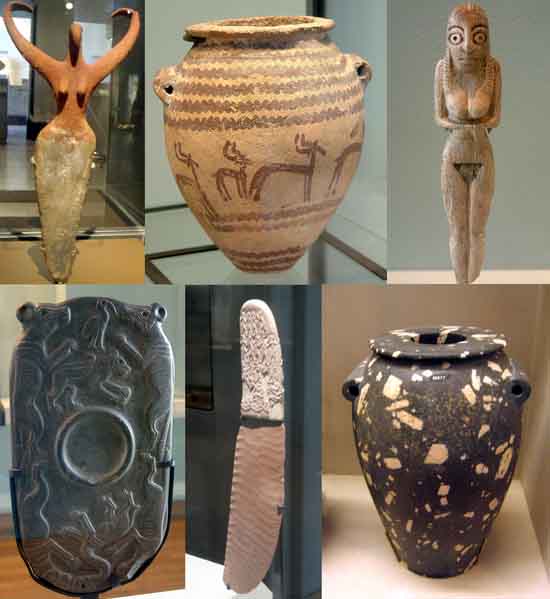

Tasian Culture

The Tasian culture was the next in Upper Egypt. This culture group is named for the burials found at Der Tasa, on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut and Akhmim. The Tasian culture group is notable for producing the earliest blacktop-ware, a type of red and brown pottery that is painted black on the top and interior. This pottery is vital to the dating of predynastic Egypt. Because all dates for the predynastic period are tenuous at best, WMF Petrie developed a system called Sequence Dating by which the relative date, if not the absolute date, of any given predynastic site can be ascertained by examining its pottery.

As the predynastic period progressed, the handles on pottery evolved from functional to ornamental, and the degree to which any given archaeological site has functional or ornamental pottery can be used to determine the relative date of the site. Since there is little difference between Tasian and Badarian pottery, the Tasian Culture overlaps the Badarian range significantly. From the Tasian period onward, it appears that Upper Egypt was influenced strongly by the culture of Lower Egypt.

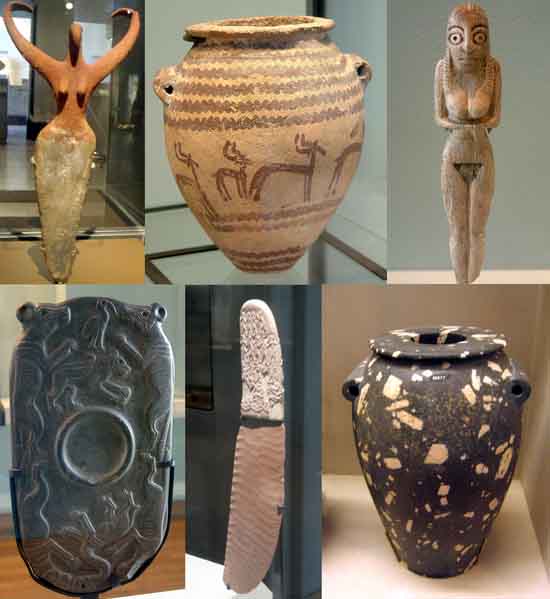

The Badarian culture, from about 4400 to 4000 BC, is named for the Badari site near Der Tasa. It followed the Tasian culture, but was so similar that many consider them one continuous period. The Badarian Culture continued to produce the kind of pottery called Blacktop-ware (albeit much improved in quality) and was assigned Sequence Dating numbers 21 - 29. The primary difference that prevents scholars from merging the two periods is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone and are thus chalcolithic settlements, while the Neolithic Tasian sites are still considered Stone Age.

Badarian flint tools continued to develop into sharper and more shapely blades, and the first faience was developed. Distinctly Badarian sites have been located from Nekhen to a little north of Abydos. It appears that the Fayum A culture and the Badarian and Tasian Periods overlapped significantly; however, the Fayum A culture was considerably less agricultural and was still Neolithic in nature.

The Badarian culture provides the earliest direct evidence of agriculture in Upper Egypt during the Predynastic Era. It flourished between 4400 and 4000 BCE,[2] and might have already existed as far back as 5000 BCE.[3] It was first identified in El-Badari, Asyut.

About forty settlements and six hundred graves have been located. Social stratification has been inferred from the burying of more prosperous members of the community in a different part of the cemetery. The Badarian economy was mostly based on agriculture, fishing and animal husbandry. Tools included end-scrapers, perforators, axes, bifacial sickles and concave-base arrowheads. Remains of cattle, dogs and sheep were found in the cemeteries. Wheat, barley, lentils and tubers were consumed.

The culture is known largely from cemeteries in the low desert. The deceased were placed on mats and buried in pits with their heads usually laid to the south, looking west. The pottery that was buried with them is the most characteristic element of the Badarian culture. It had been given a distinctive, decorative rippled surface.

The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt (ca. 4400-3000 BC), named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. Its final phase, Naqada III is coterminous with the so-called Protodynastic Period of Ancient Egypt (Early Bronze Age, 3200-3000 BC).

The Amratian culture lasted from about 4000 to 3500 BC. It is named after the site of El-Amra, about 120 km south of Badari. El-Amra is the first site where this culture group was found unmingled with the later Gerzean culture group, but this period is better attested at the Naqada site, so it also is referred to as the Naqada I culture.Black-topped ware continues to appear, but white cross-line ware, a type of pottery which has been decorated with close parallel white lines being crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, is also found at this time. The Amratian period falls between S.D. 30 and 39 in Petrie's Sequence Dating system.

Newly excavated objects attest to increased trade between Upper and Lower Egypt at this time. A stone vase from the north was found at el-Amra, and copper, which is not mined in Egypt, was imported from the Sinai, or possibly Nubia. Obsidian and a small amount of gold[46] were both definitely imported from Nubia. Trade with the oases also was likely.

New innovations appeared in Amratian settlements as precursors to later cultural periods. For example, the mud-brick buildings for which the Gerzean period is known were first seen in Amratian times, but only in small numbers. Additionally, oval and theriomorphic cosmetic palettes appear in this period, but the workmanship is very rudimentary and the relief artwork for which they were later known is not yet present.

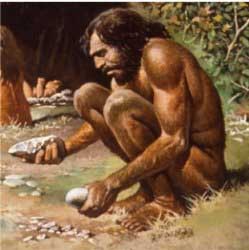

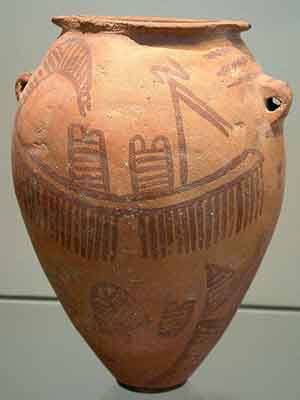

A typical Naqada II pot with ship theme

The Gerzean culture, from about 3500 to 3200 BC, is named after the site of Gerzeh. It was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation of Dynastic Egypt was laid. Gerzean culture is largely an unbroken development out of Amratian Culture, starting in the delta and moving south through upper Egypt, but failing to dislodge Amratian culture in Nubia.

Gerzean pottery is assigned values from S.D. 40 through 62, and is distinctly different from Amratian white cross-lined wares or black-topped ware. Gerzean pottery was painted mostly in dark red with pictures of animals, people, and ships, as well as geometric symbols that appear derived from animals. Also, "wavy" handles, rare before this period (though occasionally found as early as S.D. 35) became more common and more elaborate until they were almost completely ornamental.

Gerzean culture coincided with a significant decline in rainfall, and farming along the Nile now produced the vast majority of food, though contemporary paintings indicate that hunting was not entirely forgone. With increased food supplies, Egyptians adopted a much more sedentary lifestyle and cities grew as large as 5,000.

It was in this time that Egyptian city dwellers stopped building with reeds and began mass-producing mud bricks, first found in the Amratian Period, to build their cities.

Egyptian stone tools, while still in use, moved from bifacial construction to ripple-flaked construction. Copper was used for all kinds of tools, and the first copper weaponry appears here. Silver, gold, lapis, and faience were used ornamentally, and the grinding palettes used for eye-paint since the Badarian period began to be adorned with relief carvings.

The first tombs in classic Egyptian style were also built, modeled after ordinary houses and sometimes composed of multiple rooms. Although further excavations in the Delta are needed, this style is generally believed to originate there and not in Upper Egypt.

Naqada III is the last phase of the Naqada culture of ancient Egyptian prehistory, dating approximately from 3200 to 3000 BC (Shaw 2000, p. 479). It is the period during which the process of state formation, which had begun to take place in Naqada II, became highly visible, with named kings heading powerful polities. Naqada III is often referred to as Dynasty 0 or Protodynastic Period to reflect the presence of kings at the head of influential states, although, in fact, the kings involved would not have been a part of a dynasty. They would more probably have been completely unrelated and very possibly in competition with each other. Kings' names are inscribed in the form of serekhs on a variety of surfaces including pottery and tombs.

The Protodynastic Period in ancient Egypt was characterised by an ongoing process of political unification, culminating in the formation of a single state to begin the Early Dynastic Period. Furthermore, it is during this time that the Egyptian language was first recorded in hieroglyphs. There is also strong archaeological evidence of Egyptian settlements in southern Kanaan during the Protodynastic Period, which are regarded as colonies or trading entrepots.

State formation began during this era and perhaps even earlier. Various small city-states arose along the Nile. Centuries of conquest then reduced Upper Egypt to three major states: Thinis, Naqada, and Nekhen. Sandwiched between Thinis and Nekhen, Naqada was the first to fall. Thinis then conquered Lower Egypt. Nekhen's relationship with Thinis is uncertain, but these two states may have merged peacefully, with the Thinite royal family ruling all of Egypt. The Thinite kings are buried at Abydos in the Umm el-Qa'ab cemetery.

Most Egyptologists consider Narmer to be both the last king of this period and the first of the First Dynasty. He was preceded by the so-called "Scorpion King(s)", whose name may refer to, or be derived from, the goddess Serket, a special early protector of other deities and the rulers.

Wilkinson (2001) lists these early Kings as the unnamed owner of Abydos tomb B1/2 whom some interpret as Iry-Hor, King A, King B, Scorpion and/or Crocodile, and Ka. Others favor a slightly different listing.

Naqada III extends all over Egypt and is characterized by some sensational firsts:

The first graphical narratives on palettes

The first regular use of serekhs

The first truly royal cemeteries

Possibly, the first irrigation