Ancient Egyptian art is five thousand years old. It emerged and took shape in the ancient Egypt, the civilization of the Nile Valley. Expressed in paintings and sculptures, it was highly symbolic and fascinating - this art form revolves round the past and was intended to keep history alive.

In a narrow sense, Ancient Egyptian art refers to the canonical 2D and 3D art developed in Egypt from 3000 BC and used until the 3rd century. It is to be noted that most elements of Egyptian art remained remarkably stable over the 3000 year period that represents the ancient civilization without strong outside influence. The same basic conventions and quality of observation started at a high level and remained near that level over the period.

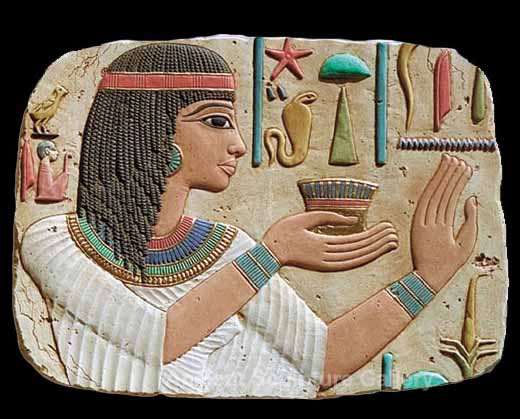

Ancient Egyptian art forms are characterized by regularity and detailed depiction of human beings and the nature, and, were intended to provide company to the deceased in the 'other world'. Artists' endeavored to preserve everything of the present time as clearly and permanently as possible. Completeness took precedence over prettiness. Some art forms present an extraordinarily vivid representation of the time and the life, as the ancient Egyptian life was lived thousand of years before.

Egyptian art in all forms obeyed one law: the mode of representing man, nature and the environment remained almost the same for thousands of years and the most admired artists were those who replicated most admired styles of the past.

Predynastic

Old Kingdom (2680 BC-2258 BC)

Middle Kingdom (2134 BC-1786 BC)

New Kingdom (1570 BC-1085 BC)

Amarna Period (1350 BC-1320 BC)

Ptolemaic

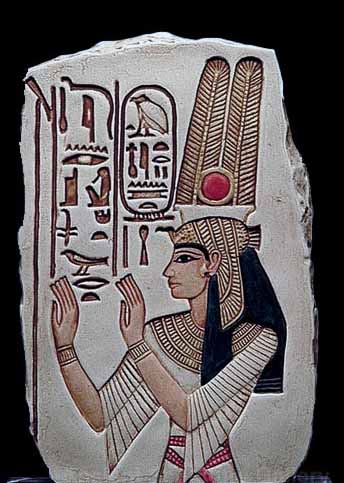

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, a cartouche is an oval with a horizontal line at one end, indicating that the text enclosed is a royal name, coming into use during the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty under Pharaoh Sneferu, replacing the earlier serekh. While the cartouche is usually vertical with a horizontal line, it is sometimes horizontal if it makes the name fit better, with a vertical line on the left. The Ancient Egyptian word for it was shenu, and it was essentially an expanded shen ring. In Demotic, the cartouche was reduced to a pair of parentheses and a vertical line.

Of the five royal titularies it was the throne name, also referred to as prenomen, and the "Son of Ra" titulary, the so-called nomen, i.e., the name given at birth, which were enclosed by a cartouche.

At times amulets were given the form of a cartouche displaying the name of a king and placed in tombs. Such items are often important to archaeologists for dating the tomb and its contents. Cartouches were formerly only worn by Pharaohs. The oval surrounding their name was meant to protect him from evil spirits in life and after death. The cartouche has become a symbol representing protection from evil and give good luck Egyptians believed that if you had your name written down in some place, then you would not disappear after you died. If a cartouche was attached to their coffin then they would have their name in at least one place. There were periods in Egyptian history when people refrained from inscribing these amulets with a name, for fear they might fall into somebody's hands conferring power over the bearer of the name.

Homeometric regularity, keen observation and exact representation of actual life and nature, and strict conformity to a set of rules regarding representation of three dimensional forms dominated the character and style of the art of ancient Egypt. Completeness and exactness were preferred to prettiness and cosmetic representation.

Because of the highly religious nature of Ancient Egyptian civilization, many of the great works of Ancient Egypt depict gods, goddesses, and Pharaohs, who were also considered divine. Ancient Egyptian art is characterized by the idea of order. Clear and simple lines combined with simple shapes and flat areas of color helped to create a sense of order and balance in the art of ancient Egypt.

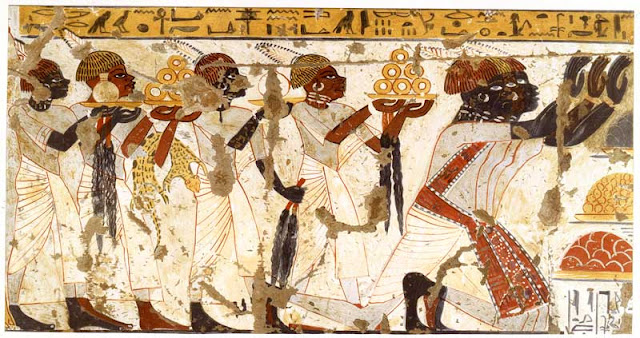

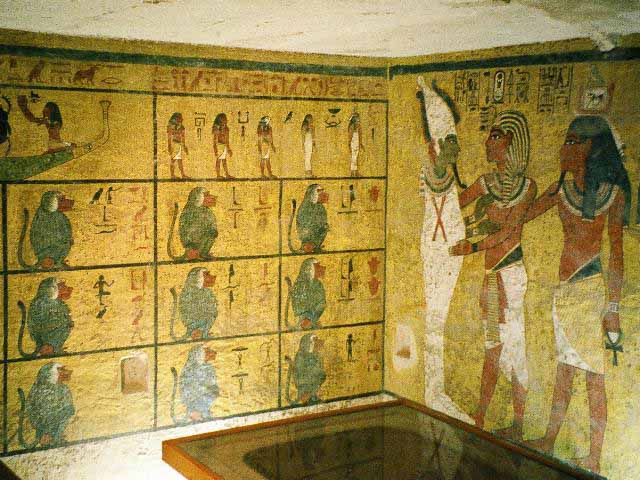

Ancient Egyptian artists used vertical and horizontal reference lines in order to maintain the correct proportions in their work. Political and religious, as well as artistic order, was also maintained in Egyptian art. In order to clearly define the social hierarchy of a situation, figures were drawn to sizes based not on their distance from the painter's point of view but on relative importance. For instance, the Pharaoh would be drawn as the largest figure in a painting no matter where he was situated, and a greater God would be drawn larger than a lesser god.

Of the materials used by the Egyptian sculptors, we find - clay, wood, metal, ivory, and stone - stone was the most plentiful and permanent, available in a wide variety of colors and hardness. Sculpture wasoften painted in vivid hues as well. Egyptian sculpture has two qualities that are distinctive; it can be characterized as cubic and frontal. It nearly always echoes in its form the shape of the stone cube or block from which it was fashioned, partly because it was an image conceived from four viewpoints. The front of almost every statue is the most important part and the figure sits or stands facing strictly to the front. This suggests to the modern viewer that the ancient artist was unable to create a naturalistic representation, but it is clear that this was not the intention.

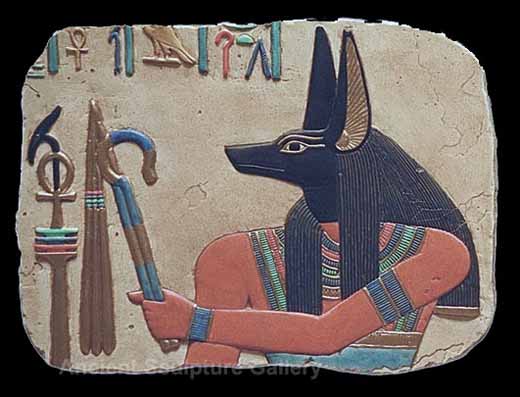

Symbolism also played an important role in establishing a sense of order. Symbolism, ranging from the Pharaoh's regalia (symbolizing his power to maintain order) to the individual symbols of Egyptian gods and goddesses, was omnipresent in Egyptian art. Animals were usually also highly symbolic figures in Egyptian art. Color, as well, had extended meaning - Blue and green represented the Nile and life; yellow stood for the sun god; and red represented power and vitality. The colors in Egyptian artifacts have survived extremely well over the centuries because of Egypt's dry climate. Despite the stilted form caused by a lack of perspective, ancient Egyptian art is often highly realistic. Ancient Egyptian artists often show a sophisticated knowledge of anatomy and a close attention to detail, especially in their renderings of animals.

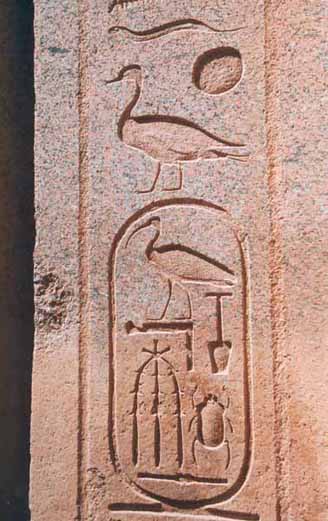

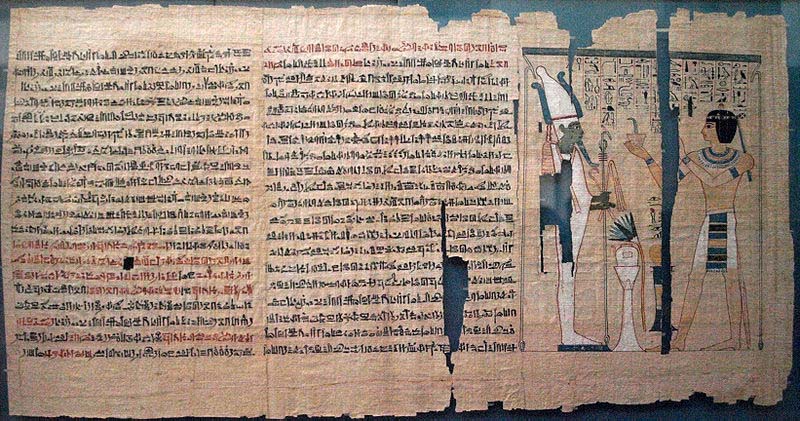

The word paper is derived from "papyrus", a plant which was cultivated in the Nile delta. Papyrus sheets were derived after processing the papyrus plant. Some rolls of papyrus discovered are lengthy, up to 10 meters. The technique for crafting papyrus was lost over time, but was rediscovered by an Egyptologist in the 1940s.

Papyrus texts illustrate all dimensions of ancient Egyptian life and include literary, religious, historical and administrative documents. The pictorial script used in these texts ultimately provided the model for two most common alphabets in the world, the Roman and the Arabic.

Ancient Egyptians used steatite ( some varieties were called soapstone) and carved small pieces of vases, amulets, images of deities, of animals and several other objects. Ancient Egyptian artists also discovered the art of covering pottery with enamel. Covering by enamel was also applied to some stone works.

Different types of pottery items were deposited in burial chambers of the dead. Some such pottery items represented interior parts of the body, like the heart and the lungs, the liver and smaller intestines , which were removed before embalming. A large number of smaller objects in enamel pottery were also deposited with the dead. It was customary to craft on the walls of the tombs cones of pottery, about six to ten inches tall, on which were engraved or impressed legends relating to the dead occupants of the tombs. These cones usually contained the names of the deceased, their titles, offices which they held, and some expressions appropriate to funeral purposes.

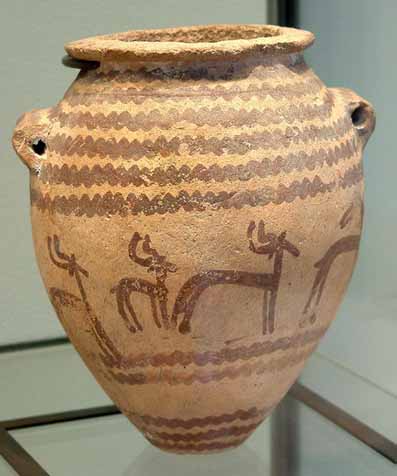

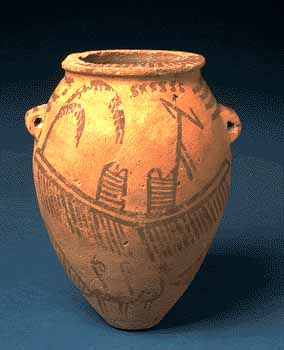

During Neolithic times, known to Egyptologists as the Predynastic period, the dead were buried in a contracted position in shallow pits dug in the sand and were surrounded by grave goods consisting of pots that probably contained food and drink, and personal items such as cosmetic palettes. These objects suggest that there was already a belief in the afterlife. The vessel illustrated here is typical of the Naqada II period, being decorated in red line on a light background. The elaborate motifs relate in part to life on the Nile, and show oared boats, water plants, standards, and birds. Other examples also include wild animals and male or female figures. Such vessels were probably made specifically for burial, rather than for everyday use.

The beginning of the arts of weaving and dyeing are lost in antiquity. Mummy cloths of varying degrees of fitness, still evidencing the dyer's skill, are preserved in many museums.

The invention of royal purple was perhaps as early as 1600 B.C. From the painted walls of tombs, temples and other structures that have been protected from exposure to weather, and from the decorated surfaces of pottery, chemical analysis often is able to give us knowledge of the materials used for such purposes.

Thus, the pigments from the tomb of Perneb (at estimated 2650 B.C.), which was presented to Metropolitan Museum of New York City in 1913, were examined by Maximilian Toch. He found that the red pigment proved to be iron oxide, hematite; a yellow consisted of clay containing iron or yellow ochre; a blue color was a finely powdered glass; and a pale blue was a copper carbonate, probably azurite; green were malachite; black was charcoal or boneblack; gray, a limestone mixed with charcoal; and a quantity of pigment remaining in a paint pot used in the decoration, contained a mixture of hematite with limestone and clay.

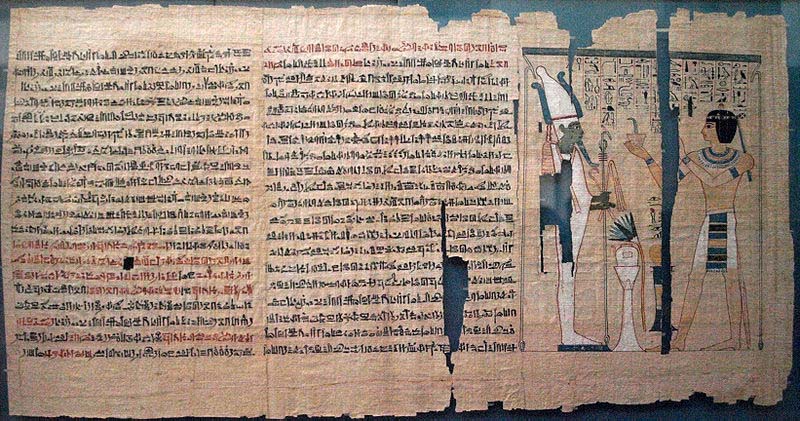

A hieroglyphic script is one consisting of a variety of pictures and symbols. Some of symbols had independent meanings, whereas some of such symbols were used in combinations. In addition, some hieroglyphs were used phonetically, in a similar fashion to the Roman alphabet. Some symbols also conveyed multiple meanings, like the legs meant to walk, to run, to go and to come. The script was written in three directions: from top to bottom, from left to right, and from right to left. This style of writing continued to be used by the ancient Egyptians for nearly 3500 years, from 3300 BC till the third century AD.

Many art works of the period contain hieroglyphs and hieroglyphs themselves constitute an amazing part of ancient Egyptian arts. Knowledge of hieroglyphic script was lost after it was superseded by other scripts. The script was decrypted by Champollion who studied the Rosetta stone for 14 years and discovered the key.

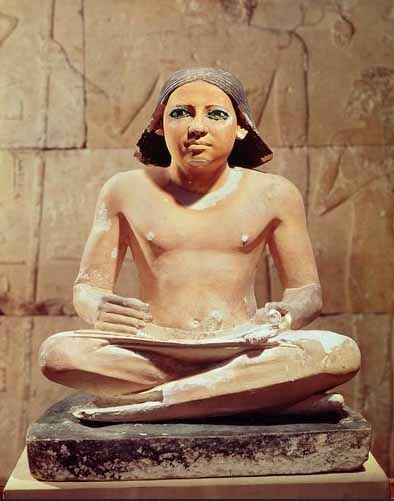

The Scribe

Ancient Egyptian literature also contains elements of Ancient Egyptian art, as the texts and connected pictures were recorded on papyrus or on wall paintings and so on. They date from the Old Kingdom to the Greco-Roman period. The subject matter of such literature related art forms include hymns to the gods, mythological and magical texts, mortuary texts. Other subject matters were biographical and historical texts, scientific premises, including mathematical and medical texts, wisdom texts dealing with instructive literature, and stories. A number of such stories from the ancient Egypt have survived thousand of years, the most famous being Cinderella, where her names is Rhodopis in the oldest version of the story.

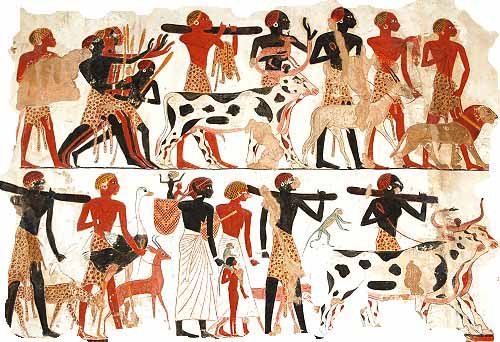

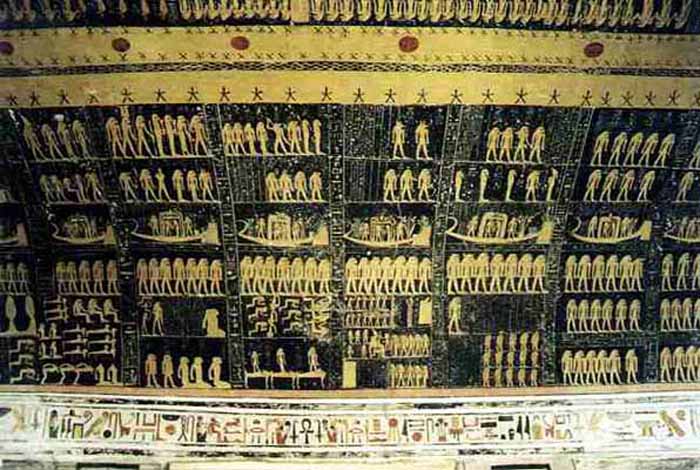

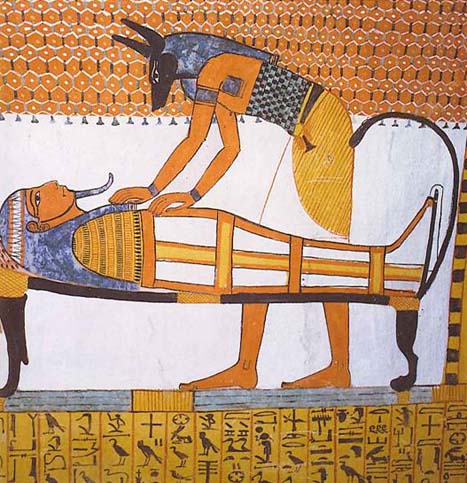

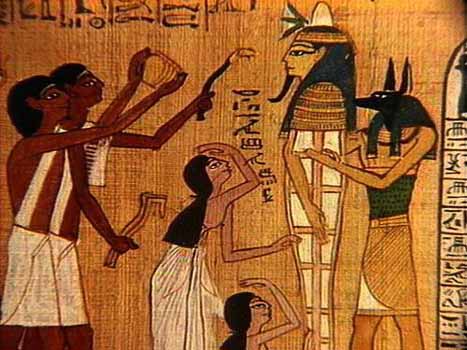

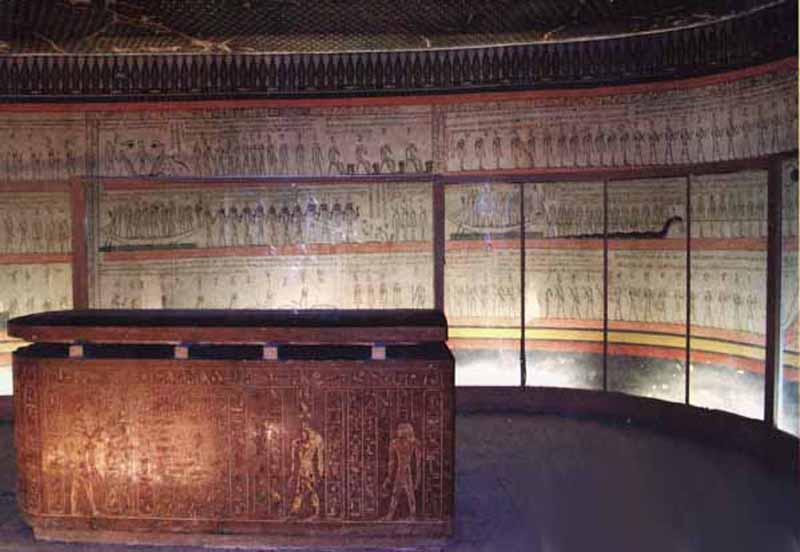

Ancient Egyptian paintings survived due to the extremely dry climate. The ancient Egyptians created paintings to make the afterlife of the deceased a pleasant place. Accordingly, beautiful paintings were created. The themes included journey through the afterworld or their protective deities introducing the deceased to the gods of the underworld. Some examples of such paintings are paintings of Osiris and Warriors.

Tomb Paintings show activities that the deceased were involved

in when they were alive and wished to carry on doing for eternity.

In the New Kingdom and later, the Book of the Dead was buried with the entombed person. It was considered important for an introduction to the afterlife.

During the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt the Pharaoh Akhenaten took the throne. He worshiped a monotheistic religion based on the worship of Aten, a sun god. Artistic changes followed political upheaval, although some stylistic changes are apparent before his reign. A new style of art was introduced that was more naturalistic than the stylized frieze favored in Egyptian art for the previous 1700 years. After Akhenaton's death, however, Egyptian artists reverted to their old styles, although there are many traces of this period's style in late art.

The Ancient Egyptian art style known as Amarna Art was a style of art that was adopted in the Amarna Period (i.e. during and just after the reign of Akhenaten in the late Eighteenth Dynasty, and is noticeably different from more conventional Egyptian art styles.

It is characterized by a sense of movement and activity in images, with figures having raised heads, many figures overlapping and many scenes are crowded and very busy.

The illustration of hands and feet were obviously thought to be important, shown with long and slender fingers, and great pains were gone to be show fingers and finger nails. Flesh was shown as being dark brown, for both males and females (contrasted with the more normal dark brown for males and light brown for females) - this could merely be convention, or depict the life blood. As is normal in Egyptian art, commoners are shown with 2 left feet (or 2 right feet).

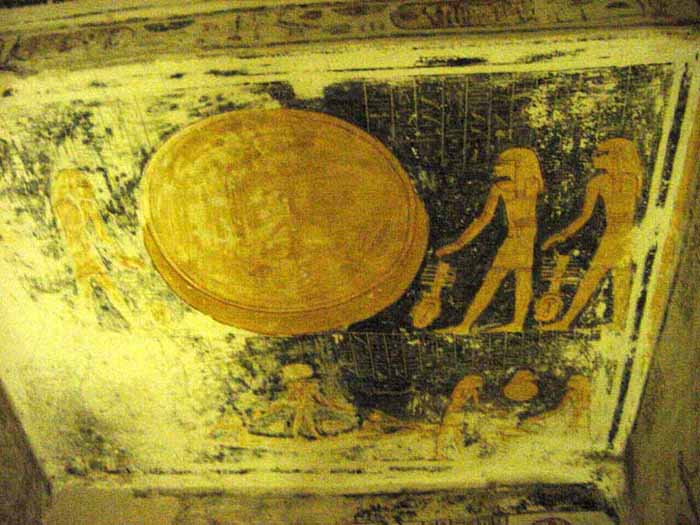

The depiction of the Royal Family is often seen as being informal, intimate and with a family closeness, but this hides the conventions of the style. Central to most scenes is the disc of the Aten, shining down on the Royal Family and literally giving life and prosperity to Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Royalty are shown with left and right feet, each with a big toe.

The decoration of tombs of non-Royals is quite different from previous eras, with not many agricultural scenes, and the image of the king being central, rather than that of the actual owner of the tomb.Obviously, the lack of depiction of gods other than the Aten makes the style of decoration quite different from the standard tomb decoration.

Sculptures from the Amarna period were a lot more relaxed and depicted people as they really were and not focusing on just some of their features.

Not many buildings from this persion have survived the ravages of later kings, partially as they were constructed out of standard size blocks, known as Talatat, which were very easy to remove and reuse.

On the Tree Of Life, the birds represent the various stages of human life. Starting in the lower right-hand corner and proceeding counter-clockwise:

In ancient Egypt, the direction east was considered the direction of life, because the sun rose in the east. West was considered the direction of death, of entering the underworld, because the sun set in the west. They believed that during the night, the sun traveled through the underworld to make its way back to the east so it could rise in the east again on the next day. On the tree of life, note that the birds representing the first four phases of life all face to the east, but the bird representing old age faces to the west, anticipating the approach of death.

In ancient Egypt, both men and women wore eye makeup, and to manufacture it they ground up mineral pigments on a palette. Such palettes were often put into graves, perhaps to ensure that the deceased had the means to grind eye makeup in the next world.

This palette is made from polished green slate, with two bird heads carved in profile at the top. Three holes have been drilled: a central one may be for hanging, whereas the other two, serving as eyes for the birds, may originally have been inlaid. The birds are possibly falcons, perhaps an early reference to the sky god Horus.

This rectangular coffin was put together from local timber for a priestess of the goddess Hathor called Nebetit. The head end is identified by a pair of stylized eyes, known as wedjat eyes, painted in a panel on the side. The coffin would have been oriented in the tomb with the head end pointing north. This would have enabled the deceased, lying on her side, magically to look out through the wedjat eyes at the sun rising on the eastern horizon - a symbol of rebirth.

The coffin has hieroglyphic inscriptions on the sides, end, and lid. The vertical inscriptions on the sides and ends identify the owner. The long horizontal inscriptions consist of "offering formulae" and ask for offerings for the 'ka' (spirit) of Nebetit. These include beef, fowl, bread, and beer, and also a request for "a good burial in her tomb in the necropolis of the western desert."

Clay funerary cones originally decorated the mudbrick facades of private tombs at Thebes. They were embedded in rows to form friezes and may have been intended to represent the ends of roof beams. The flattened base of each cone, which was all that remained visible, was stamped with the titles and name of the tomb owner. The cone shown here bears the name of Merymose, the viceroy of Nubia during the reign of Amenhotep III.

The cone bears three columns of hieroglyphic text reading from left to right. The name of Merymose is found in the third column. The first column and the top of the second form the phrase "revered before Osiris." This is followed by "king's son of Kush," the title given to the viceroy of Nubia, a territory to the south of Egypt stretching into modern northern Sudan that was conquered and ruled by the Egyptians during the New Kingdom (1550 - 1070 B.C.).

The goddess Isis, sister-consort of Osiris, god of the dead, is represented seated with her son placed at a right angle to her on her lap. She wears a tight-fitting dress and a vulture headdress surmounted by a sun disk enclosed by a pair of cow's horns, which are now broken. The horns and sun disk were originally associated with the goddess Hathor, but later they were used by Isis too. The child is supported by his mother's left arm, while her right hand offers her breast for suckling.

Horus is given the attributes of a child, being shown naked, with a single lock of hair falling on the right side of his otherwise shaven head, and sucking his forefinger. However, he is also closely associated with the ideal of kingship - the living king being a manifestation of Horus - and so he wears a uraeus (cobra), a symbol of kingship, on his forehead.

Isis was revered as an emblem of motherhood and protector of young children. Possibly due to the shift of political power to the Delta, where in myth Isis raised Horus in secret, the cult of Isis and the child Horus strengthened from the Third Intermediate period onward, and during the Greco-Roman period spread widely through the ancient world. After the Emperor Constantine had made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, the mother-child image formerly attached to Isis and Horus reemerged in representations of the Virgin and Child.

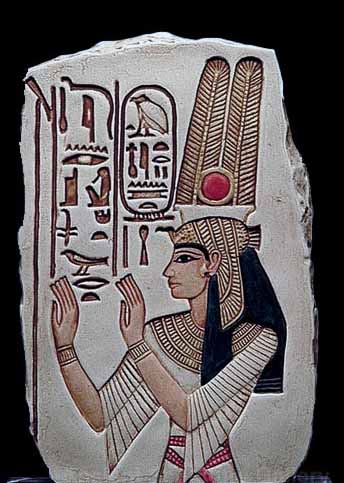

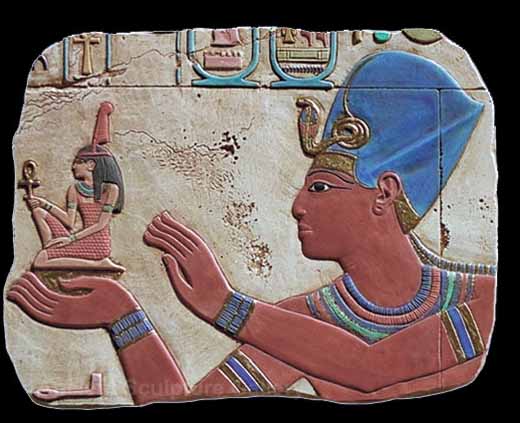

This fragment of temple relief comes from a scene that would have shown the king offering to a standing or seated deity drawn on the same scale. The roundly modeled high relief used here began to appear during the Late period and reached its peak under the Ptolemies. Unfortunately, the royal cartouche is too damaged for the name of the king to be identified lid depicts the deceased as a mummy wearing a divine, tripartite wig and the long, braided beard associated with Osiris, god of the underworld, with whom the deceased is identified.

The Book of the Dead is a funerary text that emerged in the New Kingdom as a descendant of the

Mummification

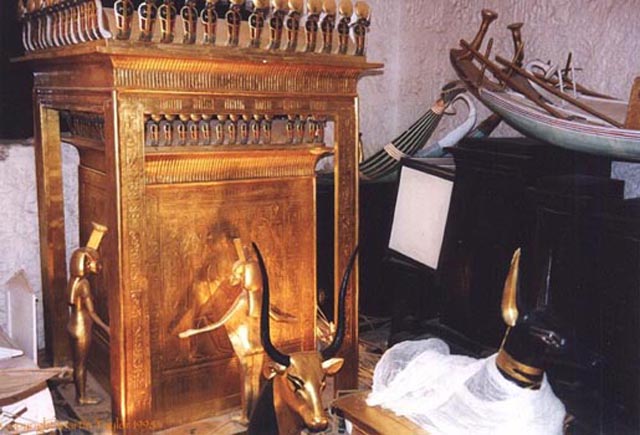

Canopic jars were used by the Ancient Egyptians during the mummification process to store and preserve the viscera of their owner for the afterlife. They were commonly either carved from limestone or were made of pottery. These jars were used by Ancient Egyptians from the time of the Old Kingdom up until the time of the Late Period or the Ptolemaic Period, by which time the viscera were simply wrapped and placed with the body. The viscera were not kept in a single canopic jar: each jar was reserved for specific organs. The name "canopic" reflects the mistaken association by early Egyptologists with the Greek legend of Canopus. Canopic jars of the Old Kingdom were rarely inscribed, and had a plain lid. In the Middle Kingdom inscriptions became more usual, and the lids were often in the form of human heads. By the Nineteenth dynasty each of the four lids depicted one of the four sons of Horus, as guardians of the organs.

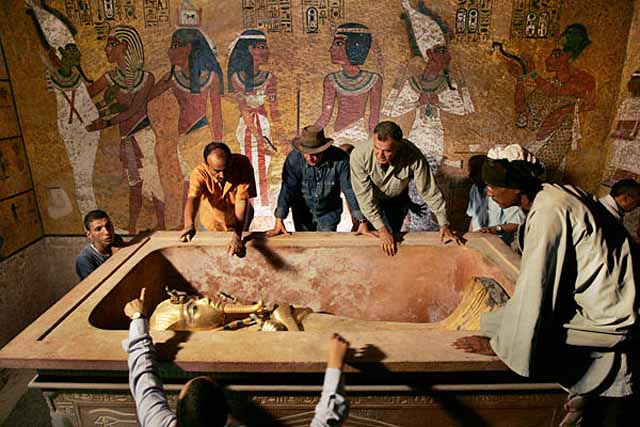

In order to enter the afterlife, it was important that the deceased have a proper burial with all the correct rituals and traditional funerary equipment. First, the body had to be preserved through mummification, a process by which it was artificially dehydrated and then wrapped in linen bandages. The invention of mummification may have stemmed from the initial practice during predynastic times of burying bodies directly in the ground. The preservative properties of the hot, desiccating sand may have suggested to the Egyptians that survival of the body was necessary for continued existence in the afterlife. Later, in

the Early Dynastic period, when the body was no longer directly surrounded by sand but was placed in a specially constructed burial chamber, the natural processes of decay set in. When they discovered this, the Egyptians over the course of centuries developed a way of keeping the body intact using resins and the naturally occurring salt, natron.

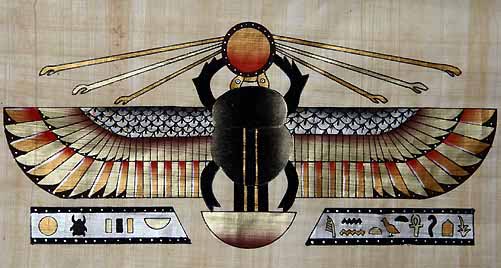

The winged scarab symbolized self-creation. This potent symbolism appears in tomb paintings, manuscripts, hieroglyphic inscriptions on buildings and carvings. In addition to its use as an amulet for the living and the dead, scarabs adorned jewelry including necklaces, bracelets, wrist cuffs and wide decorative collars. A bracelet from the tomb of Tutankhamun featured a bright blue scarab holding a cartouche between its front legs. A cartouche is an oval frame that encloses a name. The ancient Egyptians sometimes painted or carved scarabs on a deceased person's sarcophagus, the human-shaped coffin that held the mummy. Scarabs often hold a sun disk over their heads.

This wooden anthropoid coffin consists of a separate bottom and lid. It is plastered and painted on the outside, but the inside was left undecorated. It is made of irregular pieces of native Egyptian wood, and gaps between planks are filled in with mud. The underside of the base is decorated with a large figure of the goddess of the west, recognizable by the falcon emblem, the hieroglyph for west, that she wears on her head. Because the sun sets in the west, where it was believed to enter the underworld, the goddess was associated with the necropolis and helped the dead make the passage from this life to the next. As such, she often appears in tombs and on coffins.

Below an elaborate collar, a winged goddess with a sun disk on her head kneels with arms outstretched to protect the deceased. Beneath her, the mummy of the deceased lies on the lion bed that was used in the ritual embalming. Under the bed are four canopic jars to hold the viscera, with stoppers carved in the form of the four sons of Horus. These beings appear again on the lower part of the lid with mummified bodies. Between them are five columns of text. The outer two identify the figures, and the three middle ones contain the traditional offering formula asking for a series of benefits for the deceased in the next life. The name of the owner would have been included at the end of this text but is now lost through damage. Figures of Anubis, the god of embalming, in the form of two black jackals lying on pedestals decorate the foot of the coffin.

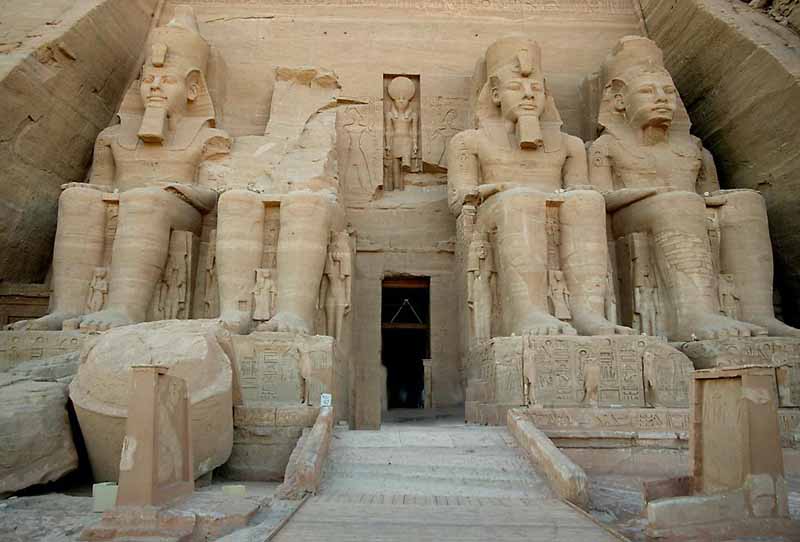

The ancient art of Egyptian sculpture evolved to represent the ancient Egyptian gods, and Pharaohs, the divine kings and queens, in physical form. Massive and magnificent statues were built to represent gods and famous kings and queens. These statues were intended to give eternal life to the ŇgodÓ kings and queens, as also to enable the subjects to see them in physical forms.

Very strict conventions were followed while crafting statues: male statues were darker than the female ones; in seated statues, hands were required to be placed on knees and specific rules governed appearance of every Egyptian god. For example, the sky god (Horus) was essentially to be represented with a falconŐs head, the god of funeral rites (Anubis) was to be always shown with a jackalŐs head. Artistic works were ranked according to exact compliance with all the conventions, and the conventions were followed so strictly that over three thousand years, very little changed in the appearance of statutes.

Mechanical Dog: A 'good boy' from ancient Egyptian that has a red tongue and barks Live Science - March 17, 2025

Posed as if leaping through the air, this carved ivory dog opens its mouth as a lever is pushed up and down, revealing two lower teeth and a red tongue. The dog, which was discovered in an ancient Egyptian tomb, is a reminder that these domesticated canines have been beloved pets for at least 3,400 years.

Ramesses II at Abu Simbel

Ancient Flying Vehicles

Egyptian Dynasties

Egyptian Gods and Goddesses

The Tomb of King Tut is much smaller than, any of the other kings tombs, with plain walls, until you reach the burial chamber. It took almost a decade of meticulous and painstaking work to empty the tomb of Tutankhamen. Around 3500 individual items were recovered. Tutankhamen is the only pharaoh, in the Valley of the Kings, still to have his mummy in its original burial location.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS