Body piercing, a form of body modification, is the practice of puncturing or cutting a part of the human body, creating an opening in which jewelry may be worn. The word piercing can refer to the act or practice of body piercing, or to an opening in the body created by this act or practice. Although the history of body piercing is obscured by popular misinformation and by a lack of scholarly reference, ample evidence exists to document that it has been practiced in various forms by both sexes since ancient times throughout the world.

Ear piercing and nose piercing have been particularly widespread and are well represented in historical records and among grave goods. The oldest mummified remains ever discovered were sporting earrings, attesting to the existence of the practice more than 5,000 years ago. Nose piercing is documented as far back as 1500 BC.

Piercings of these types have been documented globally, while lip and tongue piercings were historically found in African and American tribal cultures. Nipple and genital piercing have also been practiced by various cultures, with nipple piercing dating back at least to Ancient Rome while genital piercing is described in Ancient India c. 320 to 550 CE. The history of navel piercing is less clear. The practice of body piercing has waxed and waned in Western culture, but it has experienced an increase of popularity since World War II, with sites other than the ears gaining subcultural popularity in the 1970s and spreading to mainstream in the 1990s.

The reasons for piercing or not piercing are varied. Some people pierce for religious or spiritual reasons, while others pierce for self-expression, for aesthetic value, for sexual pleasure, to conform to their culture or to rebel against it. Some forms of piercing remain controversial, particularly when applied to youth. The display or placement of piercings have been restricted by schools, employers and religious groups. In spite of the controversy, some people have practiced extreme forms of body piercing, with Guinness bestowing World Records on individuals with hundreds and even thousands of permanent and temporary piercings.

Contemporary body piercing practices emphasize the use of safe body piercing materials, frequently utilizing specialized tools developed for the purpose. Body piercing is an invasive procedure with some risks, including allergic reaction, infection, excessive scarring and unanticipated physical injuries, but such precautions as sanitary piercing procedures and careful aftercare are emphasized to minimize the likelihood of encountering serious problems. The healing time required for a body piercing may vary widely according to placement, from as little as a month for some genital piercings to as much as two full years for the navel.

Body adornment has only recently become a subject of serious scholarly research by archaeologists, who have been hampered in studying body piercing by a sparsity of primary sources. Early records rarely discussed the use of piercings or their meaning, and while jewelry is common among grave goods, the deterioration of the flesh that it once adorned makes it difficult to discern how the jewelry may have been used.

Also, the modern record has been vitiated with the 20th-century inventions of piercing enthusiast Doug Malloy. In the 1960s and 1970s, Malloy marketed contemporary body piercing by giving it the patina of history. His pamphlet Body & Genital Piercing in Brief included such commonly reproduced urban legends as the notion that Prince Albert invented the piercing that shares his name in order to diminish the appearance of his large penis in tight trousers, and that Roman centurions attached their capes to nipple piercings. Some of Malloy's myths are reprinted as fact in subsequently published histories of piercing.

Evidence suggests that body piercing (including ear piercing) has been practiced by peoples all over the world from ancient times. Mummified bodies with piercings have been discovered, including the oldest mummified body discovered to date, that of Otzi the Iceman, which was found in an Austrian glacier. This mummy had an ear piercing 7-11 mm in diameter.

Nose piercing and ear piercing are mentioned in the Bible. In Genesis 24:22, Abraham's servant gave a nose ring and bracelets to Rebekah, wife of his son Isaac. In Exodus 32, Aaron makes the golden calf from melted earrings. Deuteronomy 15:12-17 dictates ear piercing as a mark of slavery.

Nose piercing was practiced among the nomadic Berber and Beja tribes of Africa, and the Bedouins of the Middle East, the size of the ring denotes the wealth of the family. It is given by the husband to his wife at the marriage, and is her security if she is divorced.

Nose piercing has been common in India since the 16th century. Nose piercing was bought to India in the 16th Century from the Middle East by the Moghul emperors. In India a stud (Phul) or a ring (Nath) is usually worn in the left nostril, It is sometimes joined to the ear by a chain, and in some places both nostrils are pierced. The left side is the most common to be pierced in India, because that is the spot associated in Ayuvedra (Indian medicine) with the female reproductive organs, the piercing is supposed to make childbirth easier and lessen period pain. Some women in India pierce their noses to induce a state of submissiveness. They claim this happens by proper placement in a marma or acupuncture point.

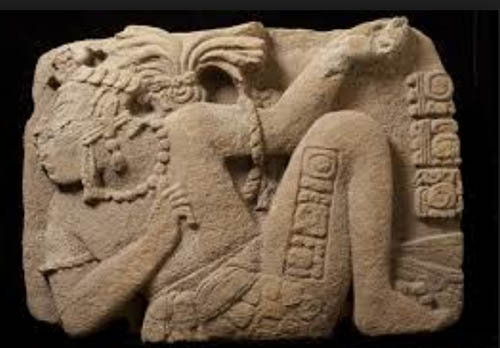

Tongue piercing was popular in Mesoamerica with the elite of Aztec and Maya civilizations, though it was carried out as part of a blood ritual and such piercings were not intended to be permanent. Ancient Mesoamericans wore jewelry in their ears, noses, and lower lips, and such decorations continue to be popular amongst indigenous peoples in these regions.

Tongue piercing was always practiced by the Haida, Kwakiutul, and Tlinglit tribes of the American Northwest. The tongue was pierced to draw blood to propitiate the gods, and to create an altered state of consciousness so that the priest or shaman could communicate with the gods.

The Pharahos of Egypt also practiced body piercing.

It has been practiced for as long as five thousand years. It has, in the beginning, as it is now, been used as a personal expression, a religious ritual, an official, or royal distinction, or more often recently, a trend in fashion.

Approximately 1440 BC. The book of Exodus 21: 5-6 describes how Hebrew servants that pledged allegiance to their master would have their ear held to a door post and pierced with an awl. This would indicate identification with a particular family.

The philosophers of Greece and the soldiers of Rome. The Centurions from ancient Rome expressed their strength and virility by displaying pierced - jeweled nipples.

All the way up to the middle classes, and the aristocracy of the 18th and 19th century. It was all but forgotten in Europe during the early 1900's, what with two world wars, and the concerns of a growing world, until the 1970's where it found itself being nurtured by London's pioneering fashion gurus and artists in the Underground!

In some parts of Australia and New Guinea one tribal custom is a pierced septum, giving the warrior a fierce savage appearance. In Borneo a man could choose to have pierced genitals for courtship and sexual enhancement reasons.

Ethiopian men and women have various facial piercings and some are identified by oversized ear discs. Lip plates in the women help to gain social status and command a higher bridal price.

Sioux Indians: a young man on his journey to manhood would have his crest pierced with eagle claws and then hang suspended in the air enduring the pain in this rite of passage.

By the 1990's, piercing had finally reached the attention of the entire globe closing the link from the ancients, to the modern.

In our culture we have brought to the mainstream some of these ancient and tribal practices as well as creating our Neo-Tribal customs. The big difference here is the expression of self choice. In our more permissive modern day society an individual can pierce their body for any number of the reasons listed above, but is not limited or obligated to a specific set of rules or conduct. Another unique principal behind modern day piercing is that unless the piercing has been overstretched, it can be viewed as temporary. The person can take out the jewelry if they desire and re-transform their "look" again and again.

Painful as it might feel, the practice of piercing a hole through the skin and inserting a piece of metal, bone, shell, ivory or glass to wear as an ornament has been around for millennia. Body piercing occurs worldwide and is practiced on men, women and children. It's grown in popularity during the past five years, especially among American teenagers, who pierce just about anything that can be pierced: ears, noses, tongues, and navels.

The most conventional form of piercing in the United States today is ear piercing. Among young and old, male and female, ear piercing is common practice and has become more mainstream for both sexes than it once was. Ear piercing can range anywhere from a single hole in one or both ears to holes along the entire rim of the ear.

Our reasons for piercing our bodies can change over time, and may vary from culture to culture. People living on the island of Cyprus 2200 years ago pierced their ears. But this evidence can also raise questions: Were earrings worn by both men and women then? Why did these ancient people wear gold bulls as adornment? Archaeologists and anthropologists are always seeking answers to questions like these.

Our reasons for piercing our bodies can change over time, and may vary from culture to culture. For example, a pair of gold earrings (left) from the Museum's Ancient Greek World gallery can tell us that the people living on the island of Cyprus 2200 years ago pierced their ears. But this evidence can also raise questions: Were earrings worn by both men and women then? Why did these ancient people wear gold bulls as adornment? Archaeologists and anthropologists are always seeking answers to questions like these.

Among the Tlingit of southeast Alaska, we know that ear piercing was directly related to an individual's rank in society. Social position was determined by the wealth of the family into which the individual was born. Although a Tlingit could rarely better his own social standing, he could raise the station of his sister's children and his grandchildren by "potlatching" (hosting a community feast). At a potlatch the host paid a member of his moiety (group) to pierce the rims of the children's ears. At additional potlatches, other holes were added. A great amount of wealth was required to host the feast and pay the person to pierce the children's ears. Consequently, the resulting series of holes marked an individual as a member of the nobility. Read more ...