Anthropology is the study of human beings, in particular the study of their physical character, evolutionary history, racial classification, historical and present-day geographic distribution, group relationships, and cultural history. Anthropology can be characterized as the naturalistic description and interpretation of the diverse peoples of the world.

Modern-day anthropology consists of two major divisions: cultural anthropology, which deals with the study of human culture in all its aspects; and physical anthropology, which is the study of human physical character, in both the past and present.

Anthropology emerged as an independent science in the late 18th century, it developed two divisions: physical anthropology, which focuses on human Evolution and variation, using methods of Physiology, Anthropometry, Genetics, and Ecology; and cultural anthropology , which includes Archaeology, Ethnology, Social Anthropology, and Linguistics.

Uruguay: Genes of a Lost South American People Point to an Unexpected History Science Alert - May 16, 2022

In spite of its location midway down the eastern seaboard of the continent of South America, Uruguay's brief history is a blur of European conflict, shaped by the colonial interests of Spanish, British, and Portuguese powers. What is starkly missing are voices from prehistory, of indigenous cultures that called the land's rolling hills and temperate plains home for thousands of years. Echoes of that lost past are finally being heard

New Research Dispels the Myth That Ancient Cultures Had Universally Short Lifespans Smithsonian - January 10, 2018

After examining the graves of over 300 people buried in Anglo Saxon English cemeteries between 475 and 625 AD, archaeologist Christine Cave of the Australian National University made a discovery that might surprise you. She found that several of the bodies in the burial grounds were over 75 years old when they died. Cave has developed a new technique for estimating the age that people died based on how

worn their teethe are. The work is dispelling myths that ancient cultures had universally short lifespans.

Archaeologists revise chronology of the last hunter-gatherers in the Near East PhysOrg - December 5, 2017

New research by a team of scientists and archaeologists suggests that the 15,000-year-old Natufian Culture could live comfortably in the steppe zone of present-day eastern Jordan .This was previously thought to be either uninhabitable or only sparsely populated. The hunter-gatherers of the Natufian Culture, which existed in modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria between c. 14,500 to 11,500 years ago, were some of the first people to build permanent houses and tend to edible plants. These innovations were probably crucial for the subsequent emergence of agriculture during the Neolithic era. Previous research had suggested that the centre of this culture was the Mount Carmel and Galilee region, and that it spread from here to other parts of the region.

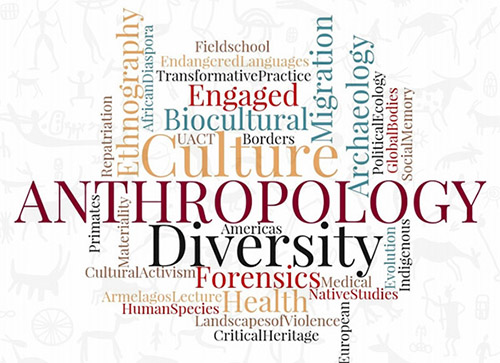

Anthropologists Confirm Link Between Cranial Anatomy and Two-Legged Walking Science Daily - September 27, 2013

Anthropology researchers have confirmed a direct link between upright two-legged (bipedal) walking and the position of the foramen magnum, a hole in the base of the skull that transmits the spinal cord. The study, published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Human Evolution, confirms a controversial finding made by anatomist Raymond Dart, who discovered the first known two-legged walking (bipedal) human ancestor, Australopithecus africanus. Since Dart's discovery in 1925, physical anthropologists have continued to debate whether this feature of the cranial base can serve as a direct link to bipedal fossil species.

Cultural anthropology is a major division of anthropology that deals with the study of culture in all its aspects and that uses the methods, concepts, and data of archaeology, ethnography and ethnology, folklore, and linguistics in its descriptions and analyses of the diverse peoples of the world.

Modern cultural anthropology as a field of research has its roots in the Age of Discovery, when technologically advanced European cultures came into extended contact with various "traditional" cultures, which for the most part the Europeans grouped indiscriminately under the general rubrics "savage" or "primitive." By the mid-19th century, such questions as the origins of the world's diverse cultures and peoples and their languages had become matters of great interest in western Europe.

The concept of evolution, as formally proposed by Charles Darwin with the publication in 1859 of The Origin of Species, lent considerable impetus to this research into the development of societies and cultures over time.

Anthropology was dominated in the latter 19th century by a linear conception of history, in which all human groups were said to pass through specified stages of cultural evolution, from a state of "savagery" to "barbarism" and finally to that of "civilized man" (i.e., western European man).

At the onset of the 20th century, the strong cultural biases of the early western European and North American anthropologists were gradually discarded in favour of a more pluralistic, relativistic outlook in which each human culture was viewed as a unique product of physical environment, cultural contacts, and other divergent factors. Out of this orientation came a new emphasis on empirical data, fieldwork, and hard evidence of human behavior and social organization within a given cultural environment. The prime exemplar of this approach was a German-born American, Franz Boas, known as the founder of the culture history school of anthropology.

Boas and his followers--notably, Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and Edward Sapir - dominated American anthropology throughout much of the 20th century. The culture history school was rooted in a functionalist approach to culture materials and sought an expression of unity between the various patterns, traits, and customs within a particular culture.

Meanwhile, in France, Marcel Mauss, founder of the Institute of Ethnology of the University of Paris, studied human societies as total systems, self-regulating and adaptive to changing circumstances in ways designed to preserve the integrity of the system. Mauss exerted considerable influence over such disparate figures as Claude Levi-Strauss in France and Bronislaw Malinowski and A.R. Radcliffe-Brown in England.

While Malinowski went on to pursue a strictly functionalist approach, Radcliffe-Brown and Levi-Strauss developed the principles of structuralism. The functionalists asserted that the only valid method of analyzing social phenomena was to define the function they performed in a society. The structuralists, by contrast, sought to identify a system or structure underlying the broad spectrum of social phenomena in particular cultures, a system of which the members of a society maintain only a dim awareness through the use of myths and symbols.

Studies of Southwest American Indian groups in the 1930s by Ruth Benedict marked the emergence of the subdiscipline of cultural anthropology known as cultural psychology. Benedict proposed that cultures in their slow development imposed a unique "psychological set" on their members, who interpreted reality along lines oriented by the culture, regardless of environmental factors.

The interrelation of culture and personality, as exemplified in the cultural value-systems of both traditional and modern societies, has become the subject of extensive research. In their fieldwork, early 20th-century cultural anthropologists produced many studies of family life and structure, marriage, kinship and local grouping, and magic and witchcraft.

During the second half of the century, while kinship studies remained a central concern, social status and power attracted more attention as researchers investigated the political and legal systems of different societies from an anthropological standpoint. More serious attention was paid to religious ideas and rituals as well. Interest shifted from African peoples, who had occupied cultural anthropologists for a quarter of a century, to peoples in India, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific Ocean islands.

The analysis of social change became a prominent area of research in the decades after World War II as many Third World countries undertook programs of economic development and industrialization. Since then, the application of computers has made possible a much greater use of quantitative data, as in studies of family and domestic group relations, marriage, divorce, and economic transactions.

Philosophical Anthropology is the discipline that seeks to unify the several empirical investigations of human nature in an effort to understand individuals as both creatures of their environment and creators of their own values.

The word anthropology was first used in the philosophical faculties of German universities at the end of the 16th century to refer to the systematic study of man as a physical and moral being. Philosophical anthropology is thus, literally, the systematic study of man conducted within philosophy or by the reflective methods characteristic of philosophy; it might in particular be thought of as being concerned with questions of the status of man in the universe, of the purpose or meaning of human life, and, indeed, with the issues of whether there is any such meaning and of whether man can be made an object of systematic study.

What actually falls under the term philosophical anthropology, however, varies with conceptions of the nature and scope of philosophy. The fact that such disciplines as physics, chemistry, and biology--which are now classified as natural sciences--were until the 19th century all branches of natural philosophy serves as a reminder that conceptions of philosophy have changed.

Twentieth-century readings of philosophical anthropology are much narrower than those of previous centuries. Four possible meanings are now accepted:

Philosophical anthropology has been used in the last sense by 20th-century antihumanists for whom it has become a term of abuse; antihumanists have insisted that if anthropology is to be possible at all it is possible only on the condition that it rejects the concept of the individual human subject. Humanism, in their eyes, yields only a prescientific, and hence a philosophical (or ideological), nonscientific anthropology.

By tracing the development of the philosophy of man, it will thus be possible to deal, in turn, with the four meanings of philosophical anthropology. First, however, it is necessary to discuss the concept of human nature, which is central to any anthropology and to philosophical debates about the sense in which and the extent to which man can be made an object of systematic, scientific study.

The concept of human nature is a common part of everyday thought. The ordinary person feels that he comes to know human nature through the character and conduct of the people he meets. Behind what they do he recognizes qualities that often do not surprise him: he forms expectations as to the sort of qualities possessed by other human beings and about the ways they differ from, for example, dogs or horses.

People are proud, sensitive, eager for recognition or admiration, often ambitious, hopeful or despondent, and selfish or capable of self-sacrifice. They take satisfaction in their achievements, have within them something called a conscience, and are loyal or disloyal. Experience in dealing with and observing people gives rise to a conception of a predictable range of conduct; conduct falling outside the range that is considered not to be worthy of a human is frequently regarded as inhuman or bestial whereas that which is exceptional--in that it lives up to standards which most people recognize but few achieve--is regarded as superhuman or saintly.

The common conception of human nature thus implicitly locates man on a scale of perfection, placing him somewhere above most animals but below saints, prophets, or angels. This idea was embodied in the theme, Hellenic in origin, of the Great Chain of Being--a hierarchical order ascending from the most simple and inert to the most complex and active: mineral, vegetable, animal, man, and finally divine beings superior to man. In the Middle Ages these divine beings constituted the various orders of angels, with God as the single, supremely perfect and omnipotent, ever-active being.

There was a tendency in this theory to take for granted the commonality among all human beings, something by virtue of which they could be classified as fully human, which differentiates them from all other animals, and which gives them their place in the order of things. Yet, as with many notions that are habitually employed, the request for a precise definition of "human nature" proves highly problematic.

The Greeks--most notably Plato and Aristotle--introduced the notion of form, nature, or essence as an explanatory, metaphysical concept. Variations on this concept were central to Western thought until the 17th century. Observation of the natural world raised the question of why creatures reproduced after their kind and could not be interbred at will and of why, for example, acorns grew into oaks and not into roses.

To explain such phenomena it was postulated that the seeds, whether plant or animal, must each already contain within them the form, nature, or essence of the species from which they were derived and into which they would subsequently develop. This pattern of explanation is preserved in the modern biological concept of a genetic code that is embodied in the DNA molecular structure of each cell. There are important differences, however, between the modern concept of a genetic code and the older, Greek-derived concept of form or essence.

First, biologists are now able to locate, isolate, experimentally analyze, and manipulate DNA molecules in what has become known as genetic engineering. Being the structures responsible for physical development, DNA molecules represent the terms by which man can be biologically characterized. Forms or essences, on the other hand, were not observable; if they were granted any independent existence, it was as immaterial entities.

The form, nature, or essence of man or of any other kind of being was posited as a principle present in the thing, determining its kind by producing in it an innate tendency to strive to develop into a perfect example of itself--to fulfill its nature and to realize its full potential as a thing of a given kind. This gave rise to a teleological, or purposive, view of the natural world in which developments were explained by reference to the goal toward which each natural thing, by its nature, strives; i.e., by reference to the ideal form it seeks to realize. By contrast, the genetic structure present in each cell is now invoked to explain the subsequent development of an organism in a "mechanistic" and nonpurposive way, in which development is shown to be dependent upon and determined by preexisting structures and conditions.

Second, genetic mutability forms an essential part of modern evolutionary biology. Not only are there genetic differences between individuals of a given species to account for differences between them in features, such as coloration, but random genetic mutation in the presence of changing environmental conditions may result in alterations to the genetic constitution of the species as a whole. Thus, in evolutionary biological theory species are not stable; natural kinds do not have the fixed, immutable forms or essences characteristic of biology before the advent of evolutionary theory.

Within either framework, if human nature is understood simply as man's special form of that which is biologically inherited in all species, there remains the delicate problem of discovering, in any given case, exactly what role environment plays in determining the actual characteristics of mature members of the species. Even in the case of purely physiological characteristics this may be far from straightforward: for example, the extent to which diet, exercise, and conditions of work determine such things as susceptibility to heart disease and cancer remains the subject of intensive scientific investigation.

In the case of behavioral and psychological characteristics, such as intelligence, the problems are multiplied to the point where they are no longer problems that can be answered by purely empirical investigation. There is room for much conceptual debate about what is meant by intelligence and over what tests, if any, can be supposed to yield a direct measure of this capacity, and thus provide evidence that an individual's level of intelligence is determined at birth (by nature) rather than by subsequent exposure to the environment (nurture) that conditions the development of all his capacities.

This debate--whether the variation in intelligence levels is a product of the conditions into which people all having the same initial potential are born, or whether it is a reflection of variations in the capacities with which they are born--is very closely related to the question of whether there is such a thing as human nature common to all human beings, or whether there are intrinsic differences among those whom we recognize as belonging to the biological species Homo sapiens.

This is because, as the name Homo sapiens suggests, man is traditionally thought to be distinguished from and privileged above other animals by virtue of his possession of reason, or intellect. When the intellect is positively valued as that which is distinctively human and which confers superiority on man, the thought that different races of people differ by nature in their intellectual capacities has been used as a justification for a variety of racist attitudes and policies.

Those of another race, of supposedly lesser intellectual development, are classified as less than fully human and therefore as needing to be accorded less than full human rights. Similarly, the thought that women are by nature intellectually inferior to men has been used as a justification for their domination by men, for refusing them education, and even for according them the legal status of property owned by men. On the other hand, if differences in adult intellectual capacity are regarded as a product of the circumstances in which potentially similar people are brought up, the attitude is to consider all as equally human but some as having been more privileged when growing up than others.

More radically, the evidence for variations in intelligence levels may be questioned by challenging the objectivity of the standards relative to which these levels are assessed. It may be argued that conceptions of what constitutes a rational or intelligent response to a situation or to a problem are themselves culturally conditioned, a product of the way in which the members of the group devising the tests and making the judgments have themselves been taught to think. Such an argument has the effect of undermining claims by any one human group to intellectual superiority over others, whether these others be their contemporaries or their own forebears. Hence, they may also be used to discredit any idea of a progressive development of human intellectual capacities.

These debates about intelligence and rationality provide an example of the complexity of the impact of evolutionary biology on conceptions of human nature, for the dominant traditions in Western thought about human nature have tended to concentrate attention more on what distinguishes man from other animals than on the strictly biological constitution that he largely shares with them. Possession of reason or intellect is far from being the only candidate considered for such a distinguishing characteristic.

Man has been characterized as essentially a tool user, or fabricator (Homo faber), as essentially social, as essentially a language user, and so on. These represent differing views concerning the fundamental feature that gives rise to all the other qualities regarded as distinctively human and which serve to mark man off from other animals.

These characteristics all center on mental, intellectual, psychological--i.e., nonphysiological -- characteristics and thus leave scope for debate about the relation between mind and body. So long as this question remains open, and so long as mental or intellectual constitution remains the central consideration in discussions of human nature, the question of changes in -- and of the possible evolution of -- human nature will remain relatively independent of those devoted to physiological change and hence of strictly biological evolution.

Until the 15th century the standard assumption was that man had a fixed nature, one that determined both his place in the universe and his destiny. The Renaissance humanists, however, proclaimed that what distinguishes man from all other creatures is that he has no nature. This was a way of asserting that man's actions are not bound by laws of nature in the way that those of other creatures are. Man is capable of taking responsibility for his own actions because he has the freedom to exercise his will. This view received two subsequent interpretations.

First, the human character is indefinitely plastic; each individual is given determinate form by the environment in which he is born, brought up, and lives. In this case, changes or developments in human beings will be regarded as the product of social or cultural changes, changes that themselves are often more rapid than biological evolution.

It is thus to disciplines such as history, politics, and sociology, rather than to biology, that one should look for an understanding of these processes. But if disciplines such as these must constitute the primary study of man, then the question of the extent to which this can be a strictly scientific study arises. The methods of history are not, and cannot be, those of the natural sciences. And the legitimacy of the claims of the so-called social or human sciences to genuine scientific status has frequently been called into question and remains a focus for debate.

Second, each individual is autonomous and must "make" himself. Assertion of the autonomy of man involves rejection of the possibility of discovering laws of human behavior or of the course of history, for freedom is precisely not being bound by law, by nature. In this case, the study of man can never be parallel to the natural sciences with their theoretical structures based on the discovery of laws of nature.

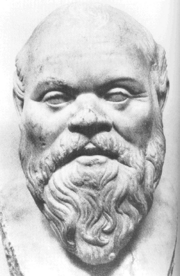

In the tradition of Western thought up to the 20th century, the study of man has been regarded as a part of philosophy. Two sayings that have been adopted as mottoes by those who see themselves as engaged in philosophical anthropology date from the 5th century BC. These are: "Man is the measure of all things" (Protagoras) and "Know thyself" (a saying from the Delphic oracle, echoed by Heracleitus and Socrates, among others). Both reflect the specific orientation of philosophical anthropology as humanism, which takes man as its starting point and treats man and the study of man as the centre, or origin, on which all other disciplines ultimately depend.

Man, the world, and God have constituted three important foci of Western thought from the beginnings of its recorded history; the relative significance of these three themes, however, has varied from one epoch to another. Western thought has laid greater stress on the existence of the individual human being than have the great speculative systems of the East; in Brahmanism, for example, personal identity dissolves in the All. But even so it was not until the Renaissance that man became the primary focus of philosophical attention and that the study of human nature began to displace theology and metaphysics as "first philosophy"--the branch of philosophy that is regarded as forming the foundation for all subsequent philosophy and that provides the framework for all scientific investigation.

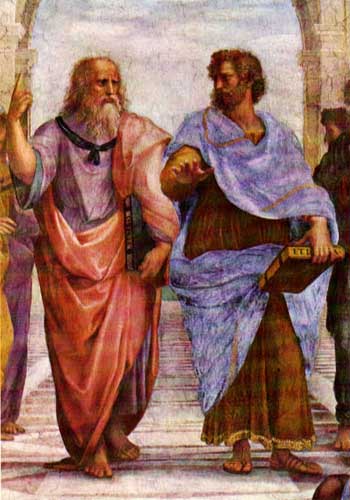

From late antiquity onward differing views of man were worked out within a framework that was laid down and given initial development by Plato and later by Aristotle. Plato and Aristotle concurred in according to metaphysics the status of first philosophy. Their differing views of man were a consequence of their differing metaphysical views.

Plato's metaphysics was dualistic: the everyday physical world of changeable things, which man comes to know by the use of his senses, is not the primary reality but is a world of appearances, or phenomenal manifestations, of an underlying timeless and unchanging reality, an immaterial realm of Forms that is knowable only by use of the intellect.

This is the view expressed in the Republic in his celebrated metaphor of the cave, where the changeable physical world is likened to shadows cast on the wall of a cave by graven images. To know the real world the occupants of the cave must first turn around and face the graven images in the light that casts the shadows (i.e., use their judgment instead of mere fantasy) and, second, must leave the cave to study the originals of the graven images in the light of day (stop treating their senses as the primary source of knowledge and start using their intellects).

Similarly, human bodily existence is merely an appearance of the true reality of human being. The identity of a human being does not derive from the body but from the character of his or her soul, which is an immaterial (and therefore nonsexual) entity, capable of being reincarnated in different human bodies. There is thus a divorce between the rational/spiritual and the material aspects of human existence, one in which the material is devalued.

Aristotle, however, rejected Plato's dualism. He insisted that the physical, changeable world made up of concrete individual substances (people, horses, plants, stones, etc.) is the primary reality. Each individual substance may be considered to be a composite of matter and form, but these components are not separable, for the forms of changeable things have no independent existence. They exist only when materially instantiated. This general metaphysical view, then, undercut Plato's body-soul dualism.

Aristotle dismissed the question of whether soul and body are one and the same as being as meaningless as the question of whether a piece of wax and the shape given to it by a seal are one. The soul is the form of the body, giving life and structure to the specific matter of a human being.

According to Aristotle, all human beings are the same in respect to form (that which constitutes them as human), and their individual differences are to be accounted for by reference to the matter in which this common form is variously instantiated (just as the different properties of golf and squash balls are derived from the materials of which they are made, while their common geometrical properties are related to their similar size and shape). This being so, it is impossible for an individual human soul to have any existence separate from the body. Reincarnation is thus ruled out as a metaphysical impossibility. Further, the physical differences between men and women become philosophically significant, the sex of a person becoming a crucial part of his or her identity.

Although Plato and Aristotle gave a different metaphysical status to forms, their role in promoting and giving point to investigations of human nature was very similar. They both agreed that it is necessary to have knowledge of human nature in order to determine when and how human life flourishes. It is through knowledge of shared human nature that we become aware of the ideals at which we should aim, achieved by learning what constitutes fulfillment of our distinctively human potential and the conditions under which this becomes possible. These ideals are objectively determined by our nature. But we are privileged in being endowed with the intellectual capacities that make it possible for us to have knowledge of this nature. Development of our intellectual capacities is thus a necessary part and precondition of a fulfilled human existence.

Western medieval culture was dominated by the Christian Church. This influence was naturally reflected in the philosophy of the period. Theology, rather than metaphysics, tended to be given primacy, even though many of the structures of Greek philosophy, including its metaphysics, were preserved. The metaphysics of form and matter was readily assimilable into Christian thought, where forms became ideas in the mind of God, the patterns according to which he created and continues to sustain the universe. Christian theology, however, modified the positions, requiring some sort of compromise between Platonic and Aristotelian views.

The creation story in the book of Genesis made man a creature among other creatures, but not a creature like other creatures; man was the product of the final act of divine initiative, was given responsibility for the Garden of Eden, and had the benefit of a direct relationship with his creator. In mythology this takes us to the Anunnaki.

The Fall and redemption, the categories of sin and grace, thus concern only the descendants of Adam, who were given a nature radically different from that of the animals and plants over which they were given dominion. Man alone can, after a life in this world, hope to participate in an eternal life that is far more important than the temporal life that he will leave.

Thus, belief in a life after death makes it impossible to regard man as wholly a natural being and entails that the physical world now inhabited by man is not the sole, or even the primary, reality. Yet, the characteristically Christian doctrine of the resurrection of the body also entails that the human body cannot be regarded as being of significance only in the mortal, physical world.

Against the background of these constraints, Christian philosophy first, through the writings of St. Augustine, gave prominence to Platonic views. But this emphasis was superseded in the 12th century by the Aristotelianism of St. Thomas Aquinas. Augustine's God is a wholly immaterial, supremely rational, transcendent creator of the universe. The twofold task of the Christian philosopher, a lover of wisdom, is to seek knowledge of the nature of God and of his own soul, the human self. For Augustine the soul is not the entire man but his better part.

There remains a Platonic tendency to regard the body as a prison for the soul and a mark of man's fallen state. One of the important consequences of Augustine's own pursuit of these two endeavors was the emphasis he came to place on the significance of free will. He argued that since the seat of the will was reason, when people exercise their will, they are acting in the image of God, the supreme rational being. Thomas Aquinas, while placing less emphasis on the will, also regarded man as acting in the image of God to the extent that he exercises and seeks to fulfill his intelligent nature. But he rejected the Platonic tendency to devalue the body, insisting that it is part of the concept of man that he have flesh and bone, as well as a soul.

But whatever the exact balance struck in the relation between the mind and body, the view of man was first and foremost as a creature of God; man was privileged by having been created in the image of God and given the gift of reason in virtue of which he also has free will and must take the burden of moral responsibility for his own actions. In order to fulfill his distinctively human nature man must thus order his thoughts and actions in such a way as to reflect the supremacy of religious values.

In popular medieval culture there was also, however, a strong undercurrent of thoroughly fatalistic thought. This was reflected in the popularity of astrology and alchemy, both of which appealed to the idea that events on Earth are governed by the influence of the heavenly bodies.

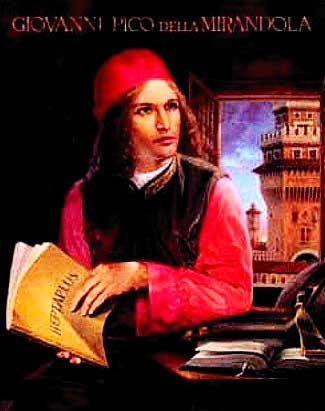

It was in the cultural context of the Renaissance, and in particular with the Italian humanists and their imitators, that the centre of gravity of reflective thought descended from heaven to earth, with man, his nature, and his capacities and limitations becoming a primary focus of philosophical attention.

This gave rise to the humanism that constitutes philosophical anthropology in the second sense. Man did not thereby cease to view himself within the context of the world, nor did he deny the existence of God; he did, however, disengage himself sufficiently from the bonds of cosmic determination and divine authority to become a centre of interest in his own eyes. In ancient literature the educated people of the West rediscovered a clear conscience instead of the guilty conscience of Christianity; at the same time, the great inventions and discoveries suggested that man could take pride in his accomplishments and regard himself with admiration.

The themes of the dignity and excellence of man were prominent in Italian humanist thought and can be found clearly expressed in Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's influential De hominis dignitate oratio (Oration on the Dignity of Man), written in 1486. In this work Pico expresses a view of man that breaks radically with Greek and Christian tradition: what distinguishes man from the rest of creation is that he has been created without form and with the ability to make of himself what he will. Being without form or nature he is not constrained, fated, or determined to any particular destiny. Thus, he must choose what he will become. (In the words of the 20th-century existentialists, man is distinguished by the fact that for him existence precedes essence.) In this way man's distinctive characteristic becomes his freedom; he is free to make himself in the image of God or in the image of beasts.

This essentially optimistic view of man was a product of the revival of Neoplatonist thought. Its optimism is based on a view of man as at least potentially a nonnatural, godlike being. But this status is now one that must be earned; man must win his right to dominion over nature and in so doing earn his place beside God in the life hereafter. He must learn both about himself and about the natural world in order to be able to achieve this.

This was, however, only one of two streams of humanist thought. The other (more Aristotelian) was essentially more pessimistic and skeptical, stressing the limitations on man's intellectual capacities.

There is an insistence on the need to be reconciled to the fact of man's humanity rather than to persist in taking seriously his superhuman pretensions and aspirations.These two differently motivated movements to focus attention on man himself, on his nature, his abilities, his earthly condition, and his relation to his material environment became more clearly articulated in the 16th and 17th centuries in the opposition between the rationalist and empiricist approaches to philosophy.

Rationalism versus Skepticism

The thought of Michel de Montaigne, the 16th-century French skeptical author of the Essais (1580-95; Essays), represented one of the first attempts at anthropological reflection (i.e., reflection centered on man, which explores his different aspects in a spirit of empirical investigation that is freed from all ties to dogma). Skepticism, the adoption of an empirical approach, and liberation from dogmatic authority are linked themes stemming from the more pessimistic views of man's capacity for knowledge.

The emphasis on man's humanity--on the limited nature of his capacities--leads to a denial that he can, even by the use of reason, transcend the realm of appearances; the only form of knowledge available to him is experimental knowledge, gained in the first instance by the use of the senses. The effect of this skeptical move was twofold.

The first effect was a liberation from the dogmatic authority of claims to knowledge of a reality behind appearances and of moral codes based on them; skeptical arguments were to the effect that human beings are so constituted that such knowledge must always be unavailable to them.

The second effect was a renewal of attention to and interest in the everyday world of appearances, which now becomes the only possible object of human knowledge and concern. The project of seeking knowledge of a reality behind appearances must be abandoned because it is beyond the scope of human understanding. And this applies as much to man himself as to the rest of the natural world; he can be known only experientially, as he appears to himself.

The anthropology of Montaigne began with a turning in upon himself; it gave priority to that reality which was within. Montaigne, however, was also witness to a renewal of knowledge brought about by numerous discoveries that made the horizons of the traditional universe expand greatly. For him, self-awareness already reflected an awareness of the surrounding world; it wondered about the "savages" of America and about the cannibals that were so different from him and yet so near; it compared the intelligence of man with that of beasts and accepted the idea of a relationship between animal existence and human existence. The idea that moral codes are the work of man, rather than reflective of an objective order, opened up the possibility of recognizing the legitimate existence of a plurality of codes and thus of the empirical study--rather than an immediate condemnation and rejection--of the customs of others.

By contrast, the work of the 17th-century French philosopher Rene Descartes represented a continuation of the theme of optimism about man's capacities for knowledge. Descartes explicitly set out, in his Meditations (first published in 1641), to beat the skeptics at their own game. He used their methods and arguments in order to vindicate claims to be able to have non-experimental knowledge of a reality behind appearances. The Meditations thus also begins with a turning in of Descartes upon himself but with the aim of finding there something that would lead beyond the confines of his own mind.

Cartesianism occupies a key position in the history of modern Western philosophy; Descartes is treated as a founding father by most of its now diverse traditions. His work is characteristic of the philosophical effort of the 17th century, which was engaged in a struggle to achieve a synthesis between old established orders and the newly proclaimed freedoms that were based on a skeptical rejection of the older orders. There are undeniable tensions in the philosophy of this period that are the product of various unsuccessful attempts to reconcile two very different views of man in relation to God and the world.

The first, the authoritarian view, was that inherited from medieval philosophy and from Thomist theology. It derived its ideal of human freedom from the Stoic conception of the wise man, who, in the 17th century was called a man of honestas (the French concept of honnetete). The man of honestas seeks freedom in the discovery of and obedience to the order and law on which the world is grounded. He believes that there is such a law, that he has a "place" in the scheme of things, and that he is bound to his fellow human beings by that nature through which he participates in this higher order. He tends to look to the authorities--whether these be church, state, or classical texts--for knowledge of this order, for it is not to be found at the level of experience; it is a "higher" order. His worldview is derived from a mixture of Platonic and Aristotelian (realist) metaphysics.

The second, the libertarian view, was that of the skeptical humanists--individualists and freethinkers, skeptical of any preestablished order, or at least of man's ability to know what it is or might be. The skeptical humanist is therefore untrammeled by it.He deploys skeptical arguments to release the individual from the constraints and demands of outer authorities. He is free to do what he wills or desires and to make his own destiny, for there can be no knowledge of objective norms. Human knowledge is limited to experience, to what is sensed, and people must therefore make their own order within experience. His view is descended from the via moderna of the medieval philosopher William of Ockham and the nominalists.

The synthesis sought was a position that would incorporate recognition of the individual and of his freedom under universal principles of order, a reconciliation of will with reason. This was sought via a nonauthoritarian conception of objective knowledge, which was the same conception that gave rise to modern science. This required, on the one hand, arguments to combat those of the skeptical freethinkers--arguments that demonstrated that there was an objective order external to human thought and that humans have the capacity not merely to know of its existence but also to discover something of its nature.

On the other hand, it was necessary to establish, against the authorities, that each individual, insofar as he is rational, has the capacity to acquire knowledge for himself, by the proper use of his reason. It is this second requirement that produced numerous treatises on the scope and limits of human understanding and on the method of acquiring knowledge. The focus was now firmly fixed on the nature of human thought and on the procedures available to it.

Descartes utilized the skeptic's own arguments to urge a meditative turning inward. This inward journey was designed to show that each human being can come to knowledge of his intellectual self and that as he does so he will find within himself the idea of God, the mark of his creator, the mark that assures him of the existence of an objective order and of the objective validity of his rational faculties. The foundation and starting point of Cartesian knowledge is, for each individual, within himself, in his experience of the certainty that he must have of his own existence and in the idea of a perfect, infinite being, in other words, an idea that he finds within himself, of a being whose essence entails God's existence, and of whose existence man can thus be assured on the basis of his idea of God.

Descartes thus preserved and built on Montaigne's emphasis on self-consciousness, and this is what marks the changed orientation in philosophy that constitutes philosophical anthropology in the stricter, second sense. As the French scientist and religious philosopher Blaise Pascal realized, the question had now become one of whether man finds within himself the basis of loyalty to a universal order of reason and law with which his own thought and will is continuous, or whether he finds, by inner examination, that order, at least insofar as it can be known, is relative to his feeling, desire, and will.

The attempt to regain an objective order by looking inward apparently fails with the failure of Descartes's proofs of the existence of God, proofs that his contemporaries (even those who, like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, were sympathetic to many aspects of the project) were quick to criticize. Reaction to this failure was twofold. In the work of rationalist philosophers, such as Spinoza, Leibniz, and Malebranche, there is a return to the classical Greek approach to philosophy through metaphysics. Empiricists, such as Locke, Condillac, and Hume, on the other hand, retain the Cartesian, introspective basis seeking what Hume calls a mitigated skepticism. This is a position that recognizes essential limitations placed on human cognitive capacities by assuming that experience is the only source of knowledge, but that affirms the value of the knowledge so gained and seeks to define the project of natural science as a quest for objective order within this domain.

John Locke, for instance, argued that while man cannot prove that the material world exists, his senses give him evidence affording all the certainty that he needs. Locke's position is, however, essentially dualist: mind and body remain distinct even though pretensions to intellectual transcendence are given up. Moreover, Locke regarded it as in principle impossible for humans to have any understanding of the relation between mind and body.

All perceptions of one's own body, as of the rest of the material world, are ideas in one's mind. It is impossible to adopt any vantage point outside oneself from which to observe the correlation between a condition of one's body and one's perception of this condition. Where other people are concerned, their bodies and behavior can be observed but an observer can have no direct perception of what is going on in their minds.

There is thus a bifurcation in the study of man. The mind and its contents are known to each person by introspection; it is presumed that the minds of all people work in basically the same way so that introspection provides evidence for human psychology.

Other people, their bodies, and their behavior are known by observation in exactly the same way that knowledge of any other natural object is obtained. One infers from their behavior that they have minds like one's own and on this basis attributes psychological states to them.

In keeping with this bifurcation Locke distinguished between the terms "man" and "person," reserving "man" for the animal species, an object of study for natural historians. "Person" is used to denote the moral subject, the being who can be held responsible for his actions and thus praised, blamed, or punished. According to Locke, what constitutes a person is a characteristic continuity of consciousness, which is not merely rational thought but the full range of mental states accessible to introspection.

Just as a tree is a characteristic organization of life functions sustained by exchanges of matter, so a person is a characteristic organization of mental functions continuing through changes in ideas (the matter of thought). A person can be held responsible for an action only if he acknowledges that action as one which he performed; i.e., one of which he is conscious and remembers having performed.

The empiricist position thus opens up the possibility of empirical studies both of man as a natural and as a moral being and puts these studies on a par with the natural sciences. But it does so in such a way that the resulting picture lacks any integral unity, for man is an incomprehensible union of body and mind.

A renewed study of the natural history of man was stimulated by European encounters with the great anthropoid apes of Africa (Angola) and Asia (the Sunda Islands) at the beginning of the 16th century. Until then Europe had known only the smaller monkeys, which were too far removed from the human species to present any confusion. The discovery of the chimpanzee and the orangutan (meaning "man of the woods" in Malay) raised such questions as whether the anthropoid, who resembles man, is an animal or a man, and why it should be considered an ape and not a man. In the climate of opinion--typified by Locke and fostered by the Royal Society of London, with its enthusiasm for empirical observation--these questions prompted the detailed observational studies of a leading member of the society, Edward Tyson.

Edward Tyson had the opportunity to study the remains of a young chimpanzee (named Pygmie) from Angola that had died in London several months after its arrival. His research was published by the Royal Society in 1699 under the title Orang-Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: or, The Anatomy of a Pygmie Compared with That of a Monkey, an Ape, and a Man. This treatise, a landmark in anthropology and comparative anatomy, is remarkable for the empirical approach used in the investigation.

Tyson's precise measurements, his complete exploration of the external and internal structures of the animal, and his minutely detailed sketches permitted him to pose what is perhaps the central problem of physical anthropology: whether it is possible to find among the anatomical or physiological characteristics of the ape the justification for asserting a radical difference between ape and man, notwithstanding all their similarities.

He analyzed in great detail the similarities and dissimilarities between a chimpanzee and a man. He emphasized the fact that the ape is a quadrumane (having four hands) rather than a quadruped (having four feet); unlike the human foot, its foot has an opposable, and thus thumb-like, big toe. The arrangement of the internal organs allows the erect posture that makes the ape similar to man. But on an analysis of the form and mass of the brain and speech apparatus, Tyson concluded that he was unable to determine, from a strictly anatomical point of view, why the ape is incapable of thinking and speaking.

Integral to the empiricism that forms the philosophical background to Tyson's work was a rejection of the whole notion of forms or essences as objectively determining fixed and strict demarcations within the natural world. Classification was the work of man imposed upon a natural continuum, which replaced the older ladder like conception of the Chain of Being. This encouraged a quest for "missing links," examples of intermediary forms between those already recognized. For example, zoophytes (invertebrate animals resembling plants, such as sponges) were said to form the link between the vegetable order and the animal order. For Tyson, the chimpanzee was the missing link between animal and man.

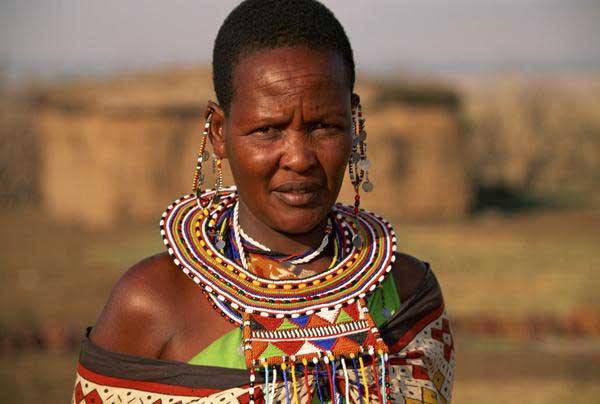

IIf physical anthropology was born out of Western man's encounter with the anthropoid apes, cultural anthropology was made necessary by his encounter with people in the rest of the world during the great voyages of discovery begun in the 15th century. Cultural anthropology became the product of the confrontation between the classical values of the West and the opposing values and customs of newly discovered civilizations.

The "savage" appeared to manifest a style of humanity that was a contradiction of the certainties that had sustained Europeans for centuries. The shock was such that the naked Indian and the cannibal were at first assumed not to belong to the human race; this approach enabled Europeans to avoid the problem. This solution was, however, rejected by Pope Paul III in 1537 in his bull, or decree, Sublimus Deus ("The Transcendent God"), according to which Indian savages were human beings; they had souls and, as such, could be initiated into the Christian religion. This left the problem of how to reconcile the increasingly manifest human diversity with the theological requirement of human unity.

One solution was to account for diversity in terms of environment, including cultural environment, and to regard the "savage" as a "primitive," as a "man of nature," who remained close to an initial state from which a privileged part of humanity had been able to remove itself by a continued effort at community and individual advancement. A study of the history of man endeavored to bring to light the successive stages through which the human species had passed along the way to the present civilized societies. The themes of "civilization" and "progress" were among the principal preoccupations of the Enlightenment.

What has come to be known as the Enlightenment is characterized by an optimistic faith in the ability of man to develop progressively by using reason. By coming to know both himself and the natural world better he is able to develop morally and materially, increasingly dominating both his own animal instincts and the natural world that forms his environment. However, the divergence between rationalist and empiricist traditions continues, giving rise to rather different interpretations of this theme.

The writings of the Scottish philosopher David Hume give a clear statement of the implications of empiricist epistemology for the study of man. Hume argued first that scientific knowledge of the natural world can consist only of conjectures as to the laws, or regularities, to be found in the sequence of natural phenomena. Not only must the causes of the phenomenal regularities remain unknown but the whole idea of a reality behind and productive of experience must be discounted as making no sense, for experience can afford nothing on the basis of which to understand such talk.

Given that this is so, and given that man also observes regularities in human behavior, the sciences of man are possible and can be put on exactly the same footing as the natural sciences. The observed regularities of human conduct can be systematically recorded and classified, and this is all that any science can or should aim to achieve. Explanation of these regularities (by reference to the essence of man) is not required in the sciences of man any more than explanation of regularities is required in the natural sciences.

Man thus becomes an object of study by natural history in the widest possible sense. All observations - whether of physiology, behavior, or culture - contribute to the empirical knowledge of man. There is no need, beyond one of convenience, to compartmentalize these observations, since the method of study is the same whether marital customs or skin colour is the topic of investigation; the aim is to record observations in a systematic fashion making generalizations where possible.

Such investigations into the natural history of man were undertaken by:

In later editions of Systema Naturae, Linnaeus presented a summary of the diverse varieties of the human species. The Asian, for example, is "yellowish, melancholy, endowed with black hair and brown eyes," and has a character that is "severe, conceited, and stingy. He puts on loose clothing. He is governed by opinion." The African is recognizable by the color of his skin, by his kinky hair, and by the structure of his face. "He is sly, lazy, and neglectful. He rubs his body with oil or grease. He is governed by the arbitrary will of his masters." As for the white European, "he is changeable, clever, and inventive. He puts on tight clothing. He is governed by laws." Here mentality, clothes, political order, and physiology are all taken into account.

French naturalist Georges Leclerc, comte de Buffon

Two individual animals or plants are of the same species if they can produce fertile offspring. Species as so defined necessarily have a temporal dimension: a species is known only through the history of its propagation. This means that it is absurd to use the same principles for classifying living and nonliving things. Rocks do not mate and have offspring, so the taxonomy of the mineral kingdom cannot be based on the same principles as that of the animal and vegetable kingdom. Similarly, according to Buffon, there is "an infinite distance" between animal and man, for "man is a being with reason, and the animal is one without reason."

Thus, "the most stupid of men can command the most intelligent of animals because he has a reasoned plan, an order of actions, and a series of means by which he can force the animal to obey him." The ape, even if in its external characteristics it is similar to man, is deprived of thought and all that is distinctive of man. Ape and man differ in temperament, in gestation period, in the rearing and growth of the body, in length of life, and in all the habits that Buffon regarded as constituting the nature of a particular being. Most important, apes and other animals lack the ability to speak.

This is significant in that Buffon saw the rise of human intelligence as a product of development of an articulated language. But this linguistic ability is the primary manifestation of the presence of reason and is not merely dependent on physiology. Animals lack speech not because they cannot produce articulated sound sequences, but because, lacking minds, they have no ideas to give meaning to these sounds. Leclerc devoted two of the 44 volumes of his Histoire Naturelle, General et Particuliere (1749-1804) to man as a zoological species.

The great German philosopher Immanuel Kant credited Hume with having wakened him from his dogmatic slumbers. But while Kant concurred with Hume in rejecting the possibility of taking metaphysics as a philosophical starting point (dogmatic metaphysics), he did not follow him in dismissing the need for metaphysics altogether. Instead he returned to the Cartesian project of seeking to find in the structure of consciousness itself something that would point beyond it.

Thus, Kant started from the same point as the empiricists, but with Cartesian consciousness--the experience of the individual considered as a sequence of mental states. But instead of asking the empiricists' question of how it is that man acquires such concepts as number, space, or color, he enquired into the conditions under which the conscious awareness of mental states--as states of mind and as classifiable states distinguished by what they purport to represent--is possible.

The empiricist simply takes the character of the human mind--consciousness and self-consciousness--for granted as a given of human nature and then proceeds to ask questions concerning how experience, presumed to come in the form of sense perceptions, gives rise to all of man's various ideas and ways of thinking.

The methods proposed for this investigation are observational, and thus the study is continuous with natural history. The enterprise overlaps with what would now be called cognitive psychology but includes introspection regarded simply as self-observation. But this clearly begs a number of questions, in particular, how the empiricist can claim knowledge of the human mind and of the character of the experience that is the supposed origin of all ideas.

Even Hume was forced to admit that self-observation, or introspection, given the supposed model of experience as a sequence of ideas and impressions, can yield nothing more than an impression of current or immediately preceding mental states. Experiential self-knowledge, on this model, is impossible. The knowing subject, by his effort to know himself, is already changing himself so that he can only know what he was, not what he is.

Thus, any empirical study, whether it be of man or of the natural world, must be based on foundations that can only be provided by a non-empirical, philosophical investigation into the conditions of the possibility of the form of knowledge sought. Without this foundation an empirical study cannot achieve any unified conception of its object and never will be able to attain that systematic, theoretically organized character that is demanded of science.

The method of such philosophical investigation is that of critical reflection--employing reason critically--not that of introspection or inner observation. It is here that the origin of what has come to be regarded as philosophical anthropology in the stricter, third sense (i.e., 20th-century Humanism) can be identified, since there is an insistence that studies of the knowing and moral subject must be founded in a philosophical study. But there remain questions about the humanity of Kant's subject.

Kant's position was still firmly dualist; the conscious subject constitutes itself through the opposition between experience of itself as free and active (in inner sense) and of the thoroughly deterministic, mechanistic, and material world (in the passive receptivity of outer sense). The subject with which philosophy is thus concerned is finite and rational, limited by the constraint that the content of its knowledge is given in the form of sense experience rather than pure intellectual intuition. This is not a differentiated individual subject but a form of which individual minds are instantiations. The ideals regulating this subject are purely rational ideals.

This tendency is even more marked in the philosophies of:

Even Hume was forced to admit that self-observation, or introspection, given the supposed model of experience as a sequence of ideas and impressions, can yield nothing more than an impression of current or immediately preceding mental states. Experiential self-knowledge, on this model, is impossible. The knowing subject, by his effort to know himself, is already changing himself so that he can only know what he was, not what he is.

Thus, any empirical study, whether it be of man or of the natural world, must be based on foundations that can only be provided by a nonempirical, philosophical investigation into the conditions of the possibility of the form of knowledge sought. Without this foundation an empirical study cannot achieve any unified conception of its object and never will be able to attain that systematic, theoretically organized character that is demanded of science.

The method of such philosophical investigation is that of critical reflection--employing reason critically--not that of introspection or inner observation. It is here that the origin of what has come to be regarded as philosophical anthropology in the stricter, third sense (i.e., 20th-century humanism) can be identified, since there is an insistence that studies of the knowing and moral subject must be founded in a philosophical study. But there remain questions about the humanity of Kant's subject.

Humanist thought is anthropocentric in that it places man at the centre and treats him as the point of origin. There are different ways of doing this, however, two of which are illustrated in the works of Locke and Kant, respectively. The first, realist, position assumes at the outset a contrast between an external, independently existing world and the conscious human subject.

In this view man is presented as standing "outside" of the physical world that he observes. This conception endorses an instrumental view of the relation between man and the nonhuman, natural world and is therefore most frequently found to be implicit in the thought of those enthusiastic about modern technological science. Nature, from this viewpoint, exists for man, who by making increasingly accurate conjectures as to the laws governing the regular succession of natural events is able to increase his ability to predict them and so to control his environment.

The second, idealist position, argues that the world exists only in being an object of human thought; it exists only by virtue of man's conceptualization of it. In the form in which Kant expressed this position the thought that constitutes the material, physical world, is that of a transcendent mind, of which the actual minds of humans are merely vehicles.

There is also a third, dialectical, form of anthropocentrism, which, although it did not emerge fully until the 19th century, was prefigured in the works of Vico and Herder. From this standpoint the relation between man and nature is regarded as an integral part to the dynamic whole of which it is a part. The world is what it is as a result of being lived in and transformed by human beings, while people, in turn, acquire their character from their existence in a particular situation within the world. Any thought about the world is concerned with a world as lived through a subject, who is also part of the world about which he thinks.

There is no possibility of transcendence in thought to some external, non-worldly standpoint. Such a position wants both to grant the independent existence of the world and to stress the active and creative role of human beings within it. It is within this relatively late form of humanism--which arose from a synthesis of elements of the Kantian position, with the insights of the Italian Giambattista Vico and the German Johann Gottfried Herder - that philosophical anthropology in the third sense can be located.

Vico's Scienza Nuova (1725; The New Science of Giambattista Vico announced not so much a new science as the need to recognize a new form of scientific knowledge. He argued (against empiricists) that the study of man must differ in its method and goals from that of the natural world. This is because the nature of man is not static and unalterable; a person's own efforts to understand the world and adapt it to his needs, physical and spiritual, continuously transform that world and himself.

Each individual is both the product and the support of a collective consciousness that defines a particular moment in the history of the human spirit. Each epoch interprets the sum of its traditions, norms, and values in such a way as to impose a model for behavior on daily life as well as on the more specialized domains of morals and religion and art. Given that those who make or create something can understand it in a way in which mere observers of it cannot, it follows that if, in some sense, people make their own history, they can understand history in a way in which they cannot understand the natural world, which is only observed by them. The natural world must remain unintelligible to man; only God, as its creator, fully understands it. History, however, being concerned with human actions, is intelligible to humans.

This means, moreover, that the succession of phases in the culture of a given society or people cannot be regarded as governed by mechanistic, causal laws. To be intelligible these successions must be explicable solely in terms of human, goal-directed activity. Such understanding is the product neither of sense perception nor of rational deduction but of imaginative reconstruction. Here Vico asserted that, even though a person's style of thought is a product of the phase of culture in which he participates, it is nonetheless possible for him to understand another culture and the transitions between cultural phases. He assumed that there is some underlying commonality of the needs, goals, and requirement for social organization that makes this possible.

Herder denied the existence of any such absolute and universally recognized goals. This denial carried the disturbing implication that the specific values and goals pursued by various human cultures may not only differ but also may not all be mutally compatible.

Hence, not only may cultural transitions not all be intelligible, but conflict may not be an attribute of the human condition that can be eliminated. If this is so, then the notion of a single code of precepts for the harmonious, ideal way of life, which underlies mainstream Western thought and to which--whether they know it or not--all human beings aspire, could not be sustained. There will be many ways of living, thinking, and feeling, each self-validating but not mutually compatible or comparable nor capable of being integrated into a harmonious pluralistic society.

The 19th century was a time of greatly increased activity in the sciences of man. There was a correspondingly rapid development of various disciplines, but this was accompanied by increasing specialization within disciplines. Perhaps the most significant theme, common to all branches of science, was the declining influence of religion.

The philosophers of the Enlightenment had concurred in thinking that the transcendence of God doomed to failure any attempt to encompass him within the framework of human discourse. Theological discourse was thus only human discourse. Herder had stated, "It is necessary to read the Bible in a human manner, for it is a book written by men for men." Even so, he insisted, "The fact that religion is integrally human is a profound sign in recognition of its truth."

But with human truth the only available truth, such a line was hard to maintain, and by the late 19th century the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche had announced that God was dead.

But the death of God also meant that the essence of God in every man was dead--that which was common to all and that in virtue of which the individual transcended the natural, material world and his purely biological nature. Also dead was the part of a person that recognized universal God-given ideals of reason and truth, goodness and beauty. There thus emerged views of man that, while integrating him more thoroughly with the natural world--treating his incarnation as an essential aspect of his condition--had to come to terms with the consequences for science, morality, and the study of man himself of the removal of a transcendent support for belief in absolute standards or ideals.

The presumption of a fixed human nature was undercut at the level of natural history by the emergence and eventual acceptance of evolutionary biology. This added a historical, developmental dimension to the natural history of man, which complimented developmental views of culture and of man as a culturally constituted being. But more importantly, evolutionary biology made man a direct descendant of nonhuman primates and suggested that the gift of reason, which so many had seen as establishing a gulf between man and animal, might too have developed gradually and might indeed have a physiological basis.

Even though Buffon had tied classification to the ability to reproduce, and had thus introduced a temporal dimension into the characterization of species, he had retained the idea of stable species. But a static classification could not explain the dynamic relations between isolated species. A primitive time line of natural history thus developed.

The relationship of families led to the idea of filiation between them according to an order of succession. The interpretation of fossils aroused impassioned debates. From them have arisen concepts of mutation (the process by which the genetic material of a cell is altered), transformism (the theory that one species is changed into another), and evolution. These concepts, already being formulated in the 18th century, were clarified in the work of Lamarck and Darwin.

The evolutionary theory of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species (1859) differed from that of Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in that it proposed a mechanistic, nonpurposive account of evolution as the product of the natural selection of randomly produced genetic mutations (survival of the fittest). Advantageous characteristics acquired by an individual were not, as Lamarck had thought, inherited and therefore could not play a role in evolutionary development.

The theme of continuity with the rest of the natural world was one that was also to be found in the very different, antiscientific thought of Romanticism, which was one of the reactions to the rise of the doctrine of mechanism and to the Industrial Revolution for which it was held responsible. The experience of the Industrial Revolution was crucial to most 19th-century thought about man. Reactions to this experience can be put into three broad categories. There were those who saw in industrialization the progressive triumph of reason over nature, making possible the march of civilization and the moral triumph of reason over animal instinct.

This was a view that continued the spirit of the Enlightenment, with its confidence in reason and the ability to advance through science. Into this category can be put the English philosopher John Stuart Mill, a stout defender of liberal individualism. Mill's philosophy was in many respects a continuation of that of Hume but with the addition of Jeremy Bentham's utilitarian view that the foundation of all morality is the principle that one should always act so as to produce the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

This ethical principle gives a prominent place to the sciences of man (which are conceived as being parallel in method to the natural sciences), their study deemed necessary for an empirical determination of the social and material conditions that produce the greatest general happiness. This is a non-dialectical, naturalistic humanism, which gives primacy to the individual and stresses the importance of his freedom. For Mill, all social phenomena, and therefore ultimately all social changes, are products of the actions of individuals.

The humanist opponents of capitalist industrialization fall into two groups, both presuming some form of dialectical humanism: those who, like Marx, retained a faith in the scientific application of reason and those who, like Goethe and Schiller, fundamentally questioned the humanity of mechanistic science and the technology it spawned.

The Romantics questioned the instrumental conception of the relation between man and nature, which is fundamental to the thinking behind much technological science. They insisted on an organic relation between man and the rest of nature. It is not man's place outside of nature that is emphasized but his situation within it.

Equally central to this view was a recognition of the historicity of human culture and a rejection of any conception of a fixed, determined human nature on which a science of man parallel in structure to the natural sciences (i.e., a science with laws, whether empirical or rational, that determine the actions and the historical development of mankind) could be based. There was a continued commitment to the perspective of the individual, and his creative relation with the world, an orientation that was carried over into the philosophical anthropology of 20th-century phenomenologists and existentialists, with their critiques of modern industrial science.

The Marxist opposition to capitalist industrialization is not to industrialization as such but to capitalist forms of it. This opposition is founded on socialism, which stresses the role of social structures; it is at the level of society--its structures and its economic base of production--that the course of history can be understood. Marx emphasized the importance of labor and work in man's relation both to the natural and to the social worlds in which he finds himself and which condition his ability to realize himself through these relationships.

Karl Marx the loss of humanity associated with capitalist industrialization, which was manifest in the alienating conditions under which members of the working class were treated as objects and thus deprived of their full status as human subjects by their industrial masters. Nonetheless, he retained a faith in scientific knowledge and in the possibility of a scientific understanding of history by integrating its economic, social, and political aspects. Marx argued, however, that it was not reason but revolution that would cause the overthrow of the capitalist system.

Common to all of these reactions is that whether they privileged reason or not they did not seek to validate the claims of reason--and hence the claims of science--by reference to a rational God. But with this transcendent guarantor removed, the question of the objectivity of rational standards and of the commonality of human thought structures became pressing.

The Cartesian starting point focused attention on thought as a sequence of ideas, knowable only to the individual concerned. Animals, even if capable of uttering structured sound sequences, were denied linguistic abilities on the ground that these sound sequences could not be the expressions of thoughts and could not have meaning; lacking minds, animals also lack ideas, the thoughts that give words their meaning.

According to this view, words are simply conventionally established vehicles for the communication of thoughts that exist prior to, and independent of, their linguistic expression.

However, if it is not assumed that human minds are all instantiations of a single transcendent mind, or that although individual they were created from a common pattern, this account of linguistic communication must appear inadequate. Since according to Cartesianism introspection is the only route to awareness of ideas, each person can only ever be aware of his own ideas, never of those of another. He could never know that his attempts to communicate succeed in calling up in another person's mind ideas similar to those in his own. Some new way of looking at linguistic communication was required, and this could be nothing short of a new starting point, a new way of thinking about thought itself.

Emergence of Philosophical Anthropology

The mood of the late 19th century, which has also dominated 20th-century philosophy, can be characterized as anti-psychologistic--a rejection of introspective, idea-oriented ways of thinking about thought, which presume that thought is prior to language. This fundamental reorientation had implications for every other aspect of the study of man.

Many writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries influenced subsequent philosophical thought about man. Each helped to transform one of the three reactions to the Industrial Revolution, to bring it into accord with the new, anti-psychologistic orientation: Frege influenced the empiricist, scientific reaction; Husserl the Romantic; and Saussure and Freud the scientific Socialist.

Sigmund Freud - He is commonly referred to as "the father of psychoanalysis" and his work has been tremendously influential in the popular imagination-popularizing such notions as the unconscious, defense mechanisms, Freudian slips and dream symbolism - while also making a long-lasting impact on fields as diverse as literature, film, marxist and feminist theories, literary criticism, philosophy, and of course, psychology.

Edmund Husserl a German philosopher, known as the father of phenomenology

Ferdinand de Saussure - Geneva-born Swiss linguist whose ideas laid the foundation for many of the significant developments in linguistics in the 20th century. He is widely considered the 'father' of 20th-century linguistics.

Gottlob Frege - German mathematician who became a logician and philosopher. He helped found both modern mathematical logic and analytic philosophy. Frege argued that if language is to be a vehicle for the expression of objective, scientific knowledge of the world, then the meaning (cognitive content) of a linguistic expression must be the same for all users of the language to which it belongs and must be determined independently of the psychological states of any individual. A word may call up a variety of ideas in the mind of an individual user, but these are not part of its meaning. Such associations may be important to the poet but are irrelevant to the scientist.

The function of language in the expression of scientific knowledge is to represent an independently existing world. The meanings of linguistic expressions must thus derive from their relation to the world, not from their relation to the minds of language users. Similarly, logic--embodying the principles of reasoning and the standards of rationality--must be concerned not with laws of human thought, but with laws of truth. The principles of correct reasoning must be justified by reference to the function of language in representing the world correctly or incorrectly rather than by reference to human psychology.