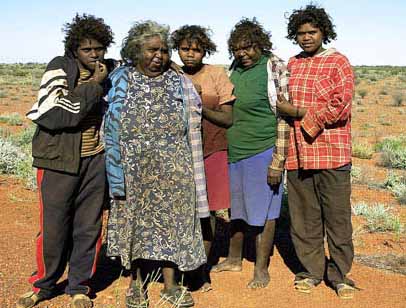

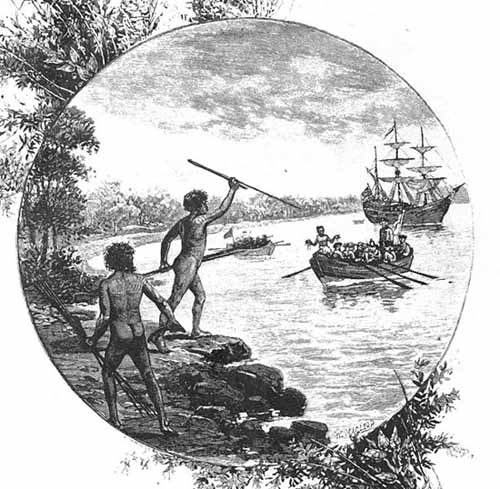

Indigenous Australians are the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia, descended from groups that existed in Australia and surrounding islands prior to European colonization. The earliest definite human remains found in Australia are those of Mungo Man, which have been dated at about 40,000 years old, although the time of arrival of the first Indigenous Australians is a matter of debate among researchers, with estimates including thermoluminescence dating to between 61,000 and 52,000 years ago, as well as a suggestion of up to 125,000 years ago.

There is great diversity among different Indigenous communities and societies in Australia, each with its own mixture of cultures, customs and languages. In present-day Australia these groups are further divided into local communities. At the time of initial European settlement, over 250 languages were spoken; it is currently estimated that 120 to 145 of these remain in use, but only 13 of these are not considered endangered.

Aboriginal people today mostly speak English, with Aboriginal phrases and words being added to create Australian Aboriginal English (which also has a tangible influence of Indigenous languages in the phonology and grammatical structure). The population of Indigenous Australians at the time of permanent European settlement has been estimated at between 318,000 and 1,000,000 with the distribution being similar to that of the current Australian population, with the majority living in the south-east, centered along the Murray River.

Since 1995, the Australian Aboriginal Flag and the Torres Strait Islander Flag have been among the official flags of Australia.

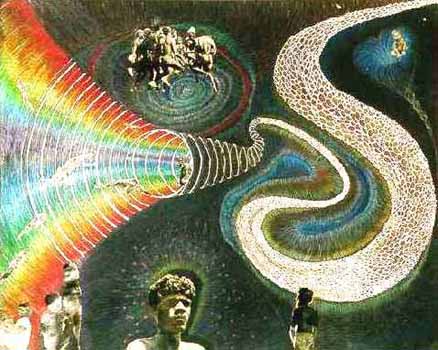

Indigenous Australians teach us that reality is a dream or illusion. Within Aboriginal belief systems, a formative epoch known as the Dreamtime stretches back into the distant past when the creator ancestors known as the First Peoples traveled across the land, creating and naming as they went. Indigenous Australia's oral tradition and religious values are based upon reverence for the land and a belief in this Dreamtime.

The Dreaming is at once both the ancient time of creation and the present-day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with its own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. Major ancestral spirits include the Rainbow Serpent, Baiame, Dirawong and Bunjil.

Traditional healers (known as Ngangkari in the Western desert areas of Central Australia) were highly respected men and women who not only acted as healers or doctors, but were generally also custodians of important Dreamtime stories.

DNA from ancient aboriginal Australian remains enables their repatriation PhysOrg - December 25, 2018

or many decades, Aboriginal Australians have campaigned for the return of ancestral remains that continue to be stored in museums worldwide. But in many instances these remains cannot be repatriated - as their geographic origin, tribal affiliation or language group was never identified. Without this information it is impossible for museums to determine appropriate custodians, which prevents their return.

Research shows it is possible to determine the origin of Aboriginal Australian remains using DNA-based methods, enabling their return to Country.

Indigenous Australians most ancient civilization on Earth, extensive DNA study confirms Telegraph - September 23, 2016

Scientists used the genetic traces of the mysterious early humans that are left in the DNA of modern populations in Papua New Guinea and Australia to reconstruct their journey from Africa around 72,000 years ago. Experts disagree on whether present-day non-African people are descended from explorers who left Africa in a single exodus or a series of distinct waves of traveling migrants. The new study supports the single migration hypothesis. It indicates that Australian aboriginal and Papuan people both originated from the same out-of Africa migration event some 72,000 years ago, along with ancestors of all other non-African populations alive today. Tracing the Papuan and Australian groups' progress showed that around 50,000 years ago they reached Sahul - a prehistoric supercontinent that once united New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania before they were separated by rising sea levels.

Looking to the Stars of Australian Aboriginal Astronomy Ancient Origins - December 30, 2015

Astronomy played an important role in many ancient societies. Through this natural science, the ancients were able to make calendars, navigate during the night, and even explore the nature of the universe through mythology and philosophy. Some civilizations well-known for their astronomical developments include the Babylonians, the ancient Egyptians, and the ancient Greeks. The astronomy of many other cultures, however, has been side-lined, as a result of the prevailing Euro-centric view of astronomy, and civilization, in general. One of these is the astronomy of the Australian Aboriginal people, considered by some to be the oldest in the world.

Could this legend be about a UFO and coincide with Ancient Alien Theory?

Aboriginal legends reveal ancient secrets to science BBC - May 19, 2015

Scientists are beginning to tap into a wellspring of knowledge buried in the ancient stories of Australia's Aboriginal peoples. But the loss of indigenous languages could mean it is too late to learn from them. The Luritja people, native to the remote deserts of central Australia, once told stories about a fire devil coming down from the Sun, crashing into Earth and killing everything in the vicinity. The local people feared if they strayed too close to this land they might reignite some otherworldly creature. The legend describes the crash landing of a meteor in Australia's Central Desert about 4,700 years ago, says University of New South Wales (UNSW) astrophysicist Duane Hamacher. It would have been a dramatic and fiery event, with the meteor blazing across the sky. As it broke apart, large fragments of metal-rich rock would have crashed to Earth with explosive force, creating a dozen giant craters.

Current scientific discoveries seem to verify Aboriginal legends passed down for millennia. Ancient cave art also suggests that ancient Aboriginals understood much about the heavens and perhaps ancient alien visitors (see Wondjina Figures below)

Aboriginal legends an untapped record of natural history written in the stars PhysOrg - March 3, 2015

Aboriginal legends could offer a vast untapped record of natural history, including meteorite strikes, stretching back thousands of years, according to new UNSW research. Dr Duane Hamacher from the UNSW Indigenous Astronomy Group has uncovered evidence linking Aboriginal stories about meteor events with impact craters dating back some 4,700 years. Dr Hamacher, an astrophysicist studying Indigenous astronomy, examined meteorite accounts from Aboriginal communities across Australia to determine if they were linked to known meteoritic events. One of the meteorite strikes, at a place called Henbury in the Northern Territory, occurred around 4,700 years ago. The level of detail contained in the local oral traditions suggested the Henbury event had been witnessed and its legend passed down through generations over thousands of years - a remarkable record.

Ancient Sea Rise Tale Told Accurately for 10,000 Years Scientific American - January 26, 2015

Without using written languages, Australian tribes passed memories of life before, and during, post-glacial shoreline inundations through hundreds of generations as high-fidelity oral history. Some tribes can still point to islands that no longer exist - and provide their original names. That's the conclusion of linguists and a geographer, who have together identified 18 Aboriginal stories - many of which were transcribed by early settlers before the tribes that told them succumbed to murderous and disease-spreading immigrants from afar - that they say accurately described geographical features that predated the last post-ice age rising of the seas.

The history of Indigenous Australians is thought to have spanned 40,000 to 45,000 years, although some estimates have put the figure at up to 80 000 years before European settlement and as low as 10,000 years. For most of this time, the Indigenous Australians lived as nomads and as hunter-gatherers with a strong dependence on the land and their agriculture for survival.

The path of Australian Aboriginal history changed radically after the 18th- and 19th-century settlement of the British: Indigenous people were displaced from their ways of life, were forced to submit to European rule, and were later encouraged to assimilate into Western culture. Since the 1960s, reconciliation has been the pursuit of European Australian - Indigenous Australian relations.

There are several hundred Indigenous peoples of Australia, many are groupings that existed before the British annexation of Australia in 1788. Before Europeans, the number was over 400.

Indigenous or groups will generally talk of their "people" and their "country". These countries are ethnographic areas, usually the size of an average European country, with around two hundred on the Australian continent at the time of White arrival.

Within each country, people lived in clan groups - extended families defined by the various forms Australian Aboriginal kinship. Inter-clan contact was common, as was inter-country contact, but there were strict protocols around this contact.

The largest Aboriginal people today is the Pitjantjatjara who live in the area around Uluru (Ayers Rock) and south into the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara in South Australia, while the second largest Aboriginal community are the Arrernte people who live in and around Alice Springs. The third largest are the Luritja, who live in the lands between the two largest just mentioned. The Aboriginal languages with the largest number of speakers today are the Pitjantjatjara, Warlpiri and Arrernte.

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands, and these peoples' descendants. Indigenous Australians are distinguished as either Aboriginal people or Torres Strait Islanders, who currently together make up about 2.6% of Australia's population.

The Torres Strait Islanders are indigenous to the Torres Strait Islands which are at the northern-most tip of Queensland near Papua New Guinea. The term "Aboriginal" has traditionally been applied to indigenous inhabitants of mainland Australia, Tasmania, and some of the other adjacent islands. The use of the term is becoming less common, with names preferred by the various groups becoming more common.

There is great diversity between different Indigenous communities and societies in Australia, each with its own unique mixture of cultures, customs and languages. In present day Australia these groups are further divided into local communities.

The population of Indigenous Australians at the time of permanent European settlement has been estimated at between 318,000 and 750,000, with the distribution being similar to that of the current Australian population, with the majority living in the south-east, centered along the Murray River.

Though Indigenous Australians are seen as being broadly related, there are significant differences in social, cultural and linguistic customs between the various Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups.

Mungo Man, whose remains were discovered in 1974 near Lake Mungo in New South Wales, is the oldest human yet found in Australia. Although the exact age of Mungo Man is in dispute, the best consensus is that he is at least 40,000 years old. Stone tools also found at Lake Mungo have been estimated, based on stratigraphic association, to be about 50,000 years old. Since Lake Mungo is in south-eastern Australia, many archaeologists have concluded that humans must have arrived in north-west Australia at least several thousand years earlier.

There is no clear or accepted origin of the indigenous people of Australia. Although they migrated to Australia through Southeast Asia they are not demonstrably related to any known Asian or Polynesian population. There is evidence of genetic and linguistic interchange between Australians in the far north and the Austronesian peoples of modern-day New Guinea and the islands, but this may be the result of recent trade and intermarriage.

It is believed that first human migration to Australia was achieved when this landmass formed part of the Sahul continent, connected to the island of New Guinea via a land bridge. It is also possible that people came by boat across the Timor Sea. The exact timing of the arrival of the ancestors of the Indigenous Australians has been a matter of dispute among archaeologists. The most generally accepted date for first arrival is between 40,000-80,000 years BP.

In 1971 finds of Aboriginal stone tools in a quarry in Penrith in New South Wales were dated to 47,000 years BP. A 48,000 BCE date is based on a few sites in northern Australia dated using thermoluminescence. A large number of sites have been radiocarbon dated to around 38,000 BCE, leading some researchers to doubt the accuracy of the thermoluminescence technique. Radiocarbon dating is limited to a maximum age of around 40,000 years. Some estimates have been given as widely as from 30,000 to 68,000 BCE. Earlier dates are requiring new techniques such as optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), and the evidence for an earlier date for arrival is growing. Charles Dortch has dated recent finds on Rottnest Island, Western Australia at 70,000 years BP.

The rock shelters at Malakunanja II (a shallow rock-shelter about 50 kilometres inland from the present coast) and of Nauwalabila I (70 kilometers further south) show evidence of used pieces of ochre - evidence for paint used by artists 60,000 years ago. Using OSL Rhys Jones has obtained a date for stone tools in these horizons dating from 53,000-60,000 years ago.

Thermoluminescence dating of the Jinmium site in the Northern Territory suggested a date of 200,000 BCE. Although this result received wide press coverage, it is not accepted by most archaeologists. Only Africa has older physical evidence of habitation by modern humans. There is also evidence of a change in fire regimes in Australia, drawn from reef deposits in Queensland, between 70 and 100,000 years ago, and the integration of human genomic evidence from various parts of the world also supports a date of before 60,000 years for the arrival of Australian Aboriginal people in the continent.

Humans reached Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago by migrating across a land bridge from the mainland that existed during the last ice age. After the seas rose about 12,000 years ago and covered the land bridge, the inhabitants there were isolated from the mainland until the arrival of European settlers.

Short statured aboriginal tribes inhabited the rainforests of North Queensland, of which the best known group is probably the Tjapukai of the Cairns area. These rainforest people, collectively referred to as Barrineans, were once considered to be a relict of an earlier wave of Negrito migration to the Australian continent, but this theory no longer finds much favor.

There has been a long history of contact between Papuan peoples of the Western Province, Torres Strait Islanders and the Aboriginal people in Cape York. The introduction of the dingo, possibly as early as 3,500 BCE, showed that contact with South East Asian peoples continued, as the closest genetic connection to the dingo seems to be the wild dogs of Thailand. This contact was not just one way, as the presence of kangaroo ticks on these dogs demonstrates. Dingoes began and evolved in Asia. The earliest known dingo-like fossils are from Ban Chiang in north-east Thailand (dated at 5,500 years BP) and from north Vietnam (5,000 years BP). According to skull morphology, these fossils occupy a place between Asian wolves (prime candidates were the pale footed (or Indian) wolf Canis lupus pallipes and the Arabian wolf Canis lupus arabs) and modern dingoes in Australia and Thailand.

Similarly Aboriginal people also seem to have lived a long time in the same environment as the now extinct Australian megafauna, stories of which are preserved in the oral culture of many Aboriginal groups. The recent European scientific belief that it was the arrival of the Australian Aboriginal people on the continent, and their introduction of fire-stick farming, that was responsible for these extinctions is contested by Aboriginal people themselves, and others who argue that mass extinctions of Australian megafauna occurred only 20,000 years ago, with the Ice Age Maxima, during which times much if not most of the continent was reduced to desert and sand-dune conditions.

There is evidence that there may have been a significant reduction in Australian Aboriginal populations during this time, and there would seem to have been specific "refugia", in which Aboriginal populations during this time were confined. Corridors between these areas seem to be routes by which people kept in contact, and they seem to have been the basis of what have been called "Songlines" to the present day.

A knowledgeable person is able to navigate across the land by repeating the words of the song, which describe the location of landmarks, waterholes, and other natural phenomena. In some cases, the paths of the creator-beings are said to be evident from their marks, or petrosomatoglyphs, on the land, such as large depressions in the land which are said to be their footprints.

By singing the songs in the appropriate sequence, Indigenous people could navigate vast distances, often traveling through the deserts of Australia's interior. The continent of Australia contains an extensive system of songlines, some of which are of a few kilometres, whilst others traverse hundreds of kilometres through lands of many different Indigenous peoples - peoples who may speak markedly different languages and have different cultural traditions.

Since a songline can span the lands of several different language groups, different parts of the song are said to be in those different languages. Languages are not a barrier because the melodic contour of the song describes the nature of the land over which the song passes. The rhythm is what is crucial to understanding the song. Listening to the song of the land is the same as walking on this songline and observing the land.

In some cases, a songline has a particular direction, and walking the wrong way along a songline may be a sacrilegious act (e.g. climbing up Uluru where the correct direction is down). Traditional Aboriginal people regard all land as sacred, and the songs must be continually sung to keep the land "alive".

Molyneaux & Vitebsky note that the Dreaming Spirits "also deposited the spirits of unborn children and determined the forms of human society," thereby establishing tribal law and totemic paradigms.

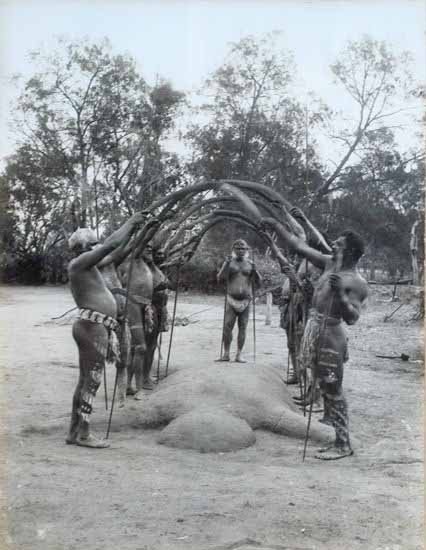

Following the Ice Age, Aboriginal people around the coast, from Arnhem Land, the Kimberley and the south west of Western Australia, all tell stories of former territories that were drowned beneath the sea with the rising coastlines after the Ice Age. It was this event that isolated the Tasmanian Aboriginal people on their island, and probably led to the extinction of Aboriginal cultures on the Bass Strait Islands and Kangaroo Island in South Australia. In the interior, the end of the Ice Age may have led to the recolonization of the desert and semi-desert areas by Aboriginal people of the Northern Territory. This may have been in part responsible for the spread of languages of the Pama–Nyungan language phylum, and secondarily responsible for the spread of male initiation rites involving circumcision.

Indigenous Australians were limited to the range of foods occurring naturally in their area, but they knew exactly when, where and how to find everything edible. Anthropologists and nutrition experts who studied the tribal diet in Arnhem Land found it to be well-balanced, with most of the nutrients modern dietitians recommend. But food was not obtained without effort. In some areas both men and women had to spend from half to two-thirds of each day hunting or foraging for food. Each day the women of the horde went into successive parts of one countryside, with wooden digging sticks and plaited dilly bags or wooden coolamons.

They dug yams and edible roots and collected fruits, berries, seeds, vegetables and insects. They killed lizards, bandicoots and other small creatures with digging sticks. The men went hunting. Small game such as birds, possums, lizards and snakes were often taken by hand. Larger animals and birds such as kangaroos and emus were speared or disabled with a thrown club, boomerang, or stone. Many indigenous devices were used to get within striking distance of prey. The men were excellent trackers and stalkers and approached their prey running where there was cover, or 'freezing' and crawling in the open. They were careful to stay downwind, and sometimes covered themselves with mud to disguise their smell.

Frequently disguises were used. Mud also served as camouflage, or the hunter held a bush in front of him while stalking in the open. He glided through water with a bunch of rushes or a lily-leaf over his head until he was close enough to pull down a water-bird. He prepared 'hides' and, with bait or bird calls, lured birds to within grabbing distance. He attracted emus, which are inquisitive birds, by imitating their movements with a stick and a bunch of feathers or some other simple device. Likewise, it was common to use the pelts of animals as a disguise, and imitate them in order to get within striking range of their herd.

Fish were sometimes taken by hand by stirring up the muddy bottom of a pool until they rose to the surface, or by placing the crushed leaves of poisonous plants in the water to stupefy them. Fish spears, nets, wicker or stone traps were also used in different areas. Lines with hooks made from bone, shell, wood or spines were used along the north and east coasts. Dugong, turtle and large fish were harpooned, the harpooner launching himself bodily from the canoe to give added weight to the thrust.

Hunting was frequently organized on co-operative lines. Groups of men combined to drive animals into a line of spearsmen, a brush-fence, or large nets. Sometimes a U-shaped area was fenced and the trapped animals killed. Animals were also trapped in snares, pits, and partly enclosed water-holes. there was a fairly clear division of labour between the sexes in food-collecting, but this was not rigidly maintained.

The main concern was to get food. Hunting was arduous, and the men often had to walk, run, or crawl long distances. In poor country the men often returned empty-handed but the women invariably collected something - perhaps only a few roots and tiny lizards - but sufficient to tide the family over. Inland, the quest for water was a life and death matter. Indigenous Australians survived where others would perish. they knew all the water holes and soaks in their area. They drained dew, and obtained water from certain trees and roots. They even dug up and squeezed out frogs which store water in their bodies.

At the time of first European contact, it is estimated that between 315,000 and 750,000 people lived in Australia, with upper estimates being as high as 1.25 million. Population levels are likely to have been largely stable for many thousands of years, and it has been estimated that between 1 and 5 billion people had lived in Australia before British colonization.

The regions of heaviest indigenous population were the same temperate coastal regions that are currently the most heavily populated. The greatest population density was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the Murray River valley in particular. However, indigenous Australians maintained successful communities throughout Australia, from the cold and wet highlands of Tasmania to the more arid parts of the continental interior. In all instances, technologies, diets and hunting practices varied according to the local environment.

Post-colonisation, the coastal indigenous populations were soon absorbed, depleted or forced from their lands; the traditional aspects of Aboriginal life which remained persisted most strongly in areas such as the Great Sandy Desert where European settlement has been sparse.

The mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from region to region. While Torres Strait Island populations were agriculturalists who supplemented their diet through the acquisition of wild foods, most Indigenous Australians were hunter-gatherers. Indigenous Australians along the coast and rivers were also expert fishermen. Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people relied on the dingo as a companion animal, using it to assist with hunting and for warmth on cold nights.

Some writers have described some mainland indigenous food and landscape management practices as "incipient agriculture". In present-day Victoria, for example, there were two separate communities with an economy based on eel-farming in complex and extensive irrigated pond systems; one on the Murray River in the state's north, the other in the south-west near Hamilton in the territory of the Djab Wurrung, which traded with other groups from as far away as the Melbourne area.

On mainland Australia no animal other than the dingo was domesticated, however domestic pigs were utilized by Torres Strait Islanders. The typical indigenous diet included a wide variety of foods, such as pig, kangaroo, emu, wombats, goanna, snakes, birds, many insects such as honey ants, Bogong moths and witchetty grubs. Many varieties of plant foods such as taro, coconuts, nuts, fruits and berries were also eaten.

A primary tool used in hunting is the spear, launched by a woomera or spear-thrower in some locales. Boomerangs were also used by some mainland indigenous peoples. The non-returnable boomerang - known more correctly as a Throwing Stick - more powerful than the returning kind, could be used to injure or even kill a kangaroo.

Boomerang

Permanent villages were the norm for most Torres Strait Island communities. In some areas mainland Indigenous Australians also lived in semi-permanent villages, most usually in less arid areas where fishing could provide for a more settled existence. Most indigenous communities were semi-nomadic, moving in a regular cycle over a defined territory, following seasonal food sources and returning to the same places at the same time each year. From the examination of middens, archaeologists have shown that some localities were visited annually by indigenous communities for thousands of years. In the more arid areas Indigenous Australians were nomadic, ranging over wide areas in search of scarce food resources.

The Indigenous Australians lived through great climatic changes and adapted successfully to their changing physical environment. There is much ongoing debate about the degree to which they modified the environment. One controversy revolves around the role of indigenous people in the extinction of the marsupial megafauna (also see Australian megafauna). Some argue that natural climate change killed the megafauna. Others claim that, because the megafauna were large and slow, they were easy prey for human hunters. A third possibility is that human modification of the environment, particularly through the use of fire, indirectly led to their extinction.

Indigenous Australians used fire for a variety of purposes: to encourage the growth of edible plants and fodder for prey; to reduce the risk of catastrophic bushfires; to make travel easier; to eliminate pests; for ceremonial purposes; for warfare and just to "clean up country." There is disagreement, however, about the extent to which this burning led to large-scale changes in vegetation patterns.

here is evidence of substantial change in indigenous culture over time. Rock painting at several locations in northern Australia has been shown to consist of a sequence of different styles linked to different historical periods.

Some have suggested, for instance, that the Last Glacial Maximum, of 20,000 years ago, associated with a period of continental wide aridity and the spread of sand-dunes, was also associated with a reduction in Aboriginal activity, and greater specialisation in the use of natural foodstuffs and products. The Flandrian transgression associated with sea-level rise, particularly in the north, with the loss of the Sahul Shelf, and with the flooding of Bass Strait and the subsequent isolation of Tasmania, may also have been periods of difficulty for affected groups.

Harry Lourandos has been the leading proponent of the theory that a period of hunter-gatherer intensification occurred between 3,000 and 1,000 BCE. Intensification involved an increase in human manipulation of the environment (for example, the construction of eel traps in Victoria), population growth, an increase in trade between groups, a more elaborate social structure, and other cultural changes. A shift in stone tool technology, involving the development of smaller and more intricate points and scrapers, occurred around this time. This was probably also associated with the introduction to the mainland of the Australian dingo.

Many indigenous communities also have a very complex kinship structure and in some places strict rules about marriage. In traditional societies, men are required to marry women of a specific moiety. The system is still alive in many Central Australian communities. To enable men and women to find suitable partners, many groups would come together for annual gatherings - commonly known as corroborees - (see below) at which goods were traded, news exchanged, and marriages arranged amid appropriate ceremonies. This practice both reinforced clan relationships and prevented inbreeding in a society based on small semi-nomadic groups.

The historical record tends to favor distinct and widespread evidence of cannibalism in indigenous communities. That the practice was observed by anthropologists from the time of European settlement and well into the 20th century has been noted by a number of writers, including W.E. Roth in his monumental study "The Queensland Aborigines". In Arnhem Land in northern Australia, a study of warfare among the Indigenous Australian Murngin people in the late 19th century found that over a 20-year period no less than 200 out of 800 men, or 25% of all adult males, had been killed in intertribal warfare.

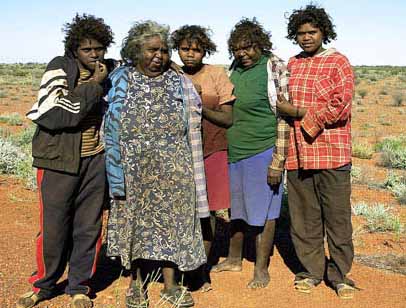

In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook claimed the east coast of Australia in the name of Great Britain and named it New South Wales. British colonization of Australia began in Sydney in 1788. The most immediate consequence of British settlement - within weeks of the first colonists' arrival - was a wave of European epidemic diseases such as chickenpox, smallpox, influenza and measles, which spread in advance of the frontier of settlement. The worst-hit communities were the ones with the greatest population densities, where disease could spread more readily. In the arid centre of the continent, where small communities were spread over a vast area, the population decline was less marked.

The second consequence of British settlement was appropriation of land and water resources. The settlers took the view that Indigenous Australians were nomads with no concept of land ownership, who could be driven off land wanted for farming or grazing and who would be just as happy somewhere else. In fact the loss of traditional lands, food sources and water resources was usually fatal, particularly to communities already weakened by disease.

Additionally, Indigenous Australians groups had a deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land, so that in being forced to move away from traditional areas, cultural and spiritual practices necessary to the cohesion and well-being of the group could not be maintained. Proximity to settlers also brought venereal disease, to which Indigenous Australians had no tolerance and which greatly reduced Indigenous fertility and birthrates. Settlers also brought alcohol, opium and tobacco, and substance abuse has remained a chronic problem for Indigenous communities ever since.

The combination of disease, loss of land and direct violence reduced the Aboriginal population by an estimated 90% between 1788 and 1900. Entire communities in the moderately fertile southern part of the continent simply vanished without trace, often before European settlers arrived or recorded their existence.

The Palawah, or Indigenous people of Tasmania, were particularly hard-hit. Nearly all of them, apparently numbering somewhere between 2,000 and 15,000 when white settlement began, were dead by the 1870s. It is widely claimed that this was the result of a genocidal policy, in the form of the "Black War". However, such claims are disputed by historian Keith Windschuttle, who claims that only 118 Aboriginal Tasmanians were killed in 1803-47 and that many of these were killed in self-defense.

Another scholar, H. A. Willis, has subsequently disputed Windschuttle's figures and has documented 188 Palawah killed by settlers in 1803–34 alone, with possibly another 145 killed during the same period. Such counts do not consider undocumented violence and must be regarded as minimum estimates. It is also claimed, but untrue, that the last Indigenous Tasmanian was Truganini, who died in 1876. This belief stems from a distinction between "full bloods" and "half castes" that is now generally regarded as racist. Palawah people survived, in missions set up on the islands of Bass Strait.

On the mainland, prolonged conflict followed the frontier of European settlement. In 1834, John Dunmore Lang wrote: "There is black blood at this moment on the hands of individuals of good repute in the colony of New South Wales of which all the waters of New Holland would be insufficient to wash out the indelible stains."

In 1838, twenty eight Indigenous people were killed at the Myall Creek massacre; the hanging of the white convict settlers responsible was the first time whites had been executed for the murder of Indigenous people. Many Indigenous communities resisted the settlers, such as the Noongar of south-western Australia, led by Yagan, who was killed in 1833.

The Kalkadoon of Queensland also resisted the settlers, and there was a massacre of over 200 people on their land at Battle Mountain in 1884. There was a massacre at Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928. Poisoning of food and water has been recorded on several different occasions. The number of violent deaths at the hands of white people is still the subject of debate, with a figure of around 10,000 - 20,000 deaths being advanced by historians such as Henry Reynolds.

Nevertheless, deadly infectious diseases like smallpox, influenza and tuberculosis were always major causes of Indigenous deaths. Smallpox alone killed more than 50% of the Aboriginal population. Reynolds, and other historians, estimate that up to 3,000 white people were killed by Indigenous Australians in the frontier violence.

By the 1870s all the fertile areas of Australia had been appropriated, and Indigenous communities reduced to impoverished remnants living either on the fringes of European communities or on lands considered unsuitable for settlement.

Some initial contact between Indigenous people and Europeans was peaceful, starting with the Guugu Yimithirr people who met James Cook near Cooktown in 1770. Bennelong served as interlocutor between the Eora people of Sydney and the British colony, and was the first Indigenous Australian to travel to England, staying there between 1792 and 1795.

Indigenous people were known to help European explorers, such as John King, who lived with a tribe for two and a half months after the ill fated Burke and Wills expedition of 1861. Also living with Indigenous people was William Buckley, an escaped convict, who was with the Wautharong people near Melbourne for thirty-two years, before being found in 1835. Many Indigenous people adapted to European culture, working as stock hands or laborers. The first Australian cricket team, which toured England in 1868, was principally made up of Indigenous players.

As the European pastoral industries developed, several economic changes came about. The appropriation of prime land and the spread of European livestock over vast areas made a traditional Indigenous lifestyle less viable, but also provided a ready alternative supply of fresh meat for those prepared to incur the settlers' anger by hunting livestock. The impact of disease and the settlers' industries had a profound impact on the Indigenous Australians' way of life.

With the exception of a few in the remote interior, all surviving Indigenous communities gradually became dependent on the settler population for their livelihood. In south-eastern Australia, during the 1850s, large numbers of white pastoral workers deserted employment on stations for the Australian gold-rushes.

Indigenous women, men and children became a significant source of labor. Most Indigenous labor was unpaid, instead Indigenous workers received rations in the form of food, clothing and other basic necessities.

In the later 19th century, settlers made their way north and into the interior, appropriating small but vital parts of the land for their own exclusive use (waterholes and soaks in particular), and introducing sheep, rabbits and cattle, all three of which ate out previously fertile areas and degraded the ability of the land to carry the native animals that were vital to Indigenous economies.

Indigenous hunters would often spear sheep and cattle, incurring the wrath of graziers, after they replaced the native animals as a food source. As large sheep and cattle stations came to dominate northern Australia, Indigenous workers were quickly recruited. Several other outback industries, notably pearling, also employed Aboriginal workers.

In many areas Christian missions provided food and clothing for Indigenous communities and also opened schools and orphanages for Indigenous children. In some places colonial governments provided some resources.

In spite of the impact of disease, violence and the spread of foreign settlement and custom, some Indigenous communities in remote desert and tropical rainforest areas survived according to traditional means until well into the 20th century.

In 1914 around 1200 Aboriginal people answered the call to arms, despite restrictions on Indigenous Australians serving in the military. As the war continued, these restrictions were relaxed as more recruits were needed. Many enlisted by claiming they were Maori or Indian.

By the 1920s, the Indigenous population had declined to between 50,000 and 90,000, and the belief that the Indigenous Australians would soon die out was widely held, even among Australians sympathetic to their situation. But by about 1930, those Indigenous Australians who had survived had acquired better resistance to imported diseases, and birthrates began to rise again as communities were able to adapt to changed circumstances.

In the Northern Territory, significant frontier conflict continued. Both isolated Europeans and visiting Asian fishermen were killed by hunter gatherers until the start of World War II in 1939. It is known that some European settlers in the centre and north of the country shot Indigenous people during this period. One particular series of killings became known as the Caledon Bay crisis, and became a watershed in the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Well into the 20th Century, Indigenous Australians were - both in Australia itself and in many other countries – the subject of widespread crude racist stereotyping. For example, the American birth control campaigner Margaret Sanger could write casually: "The aboriginal Australian, the lowest known species of the human family, just a step higher than the chimpanzee in brain development, has so little sexual control that police authority alone prevents him from obtaining sexual satisfaction on the streets" (What Every Girl Should Know, 1920).

By the end of World War II, many Indigenous men had served in the military. They were among the few Indigenous Australians to have been granted citizenship; even those that had were obliged to carry papers, known in the vernacular as a "dog license", with them to prove it. However, Aboriginal pastoral workers in northern Australia remained unfree laborers, paid only small amounts of cash, in addition to rations, and severely restricted in their movements by regulations and/or police action.

On 1 May 1946, Aboriginal station workers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia initiated the 1946 Pilbara strike and never returned to work. Mass layoffs across northern Australia followed the Federal Pastoral Industry Award of 1968, which required the payment of a minimum wage to Aboriginal station workers, as they were not paid by the Pastoralist discretion, many however were not and those who were had their money held by the government. Many of the workers and their families became refugees or fringe dwellers, living in camps on the outskirts of towns and cities.

In 1984, a group of Pintupi people who were living a traditional hunter-gatherer desert-dwelling life were tracked down in the Gibson Desert in Western Australia and brought in to a settlement. They are believed to be the last uncontacted tribe in Australia.

In 1949, the right to vote in federal elections was extended to Indigenous Australians who had served in the armed forces, or were enrolled to vote in state elections. At that time, those Indigenous Australians who lived in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory were still ineligible to vote in state elections, consequently they did not have the right to vote in federal elections.

All Indigenous Australians were given the right to vote in Commonwealth elections in Australia by the Menzies government in 1962. The first federal election in which all Aboriginal Australians could vote was held in November 1963. The right to vote in state elections was granted in Western Australia in 1962 and Queensland was the last state to do so in 1965.

The 1967 referendum, passed with a 90% majority, allowed the Commonwealth to make laws with respect to Aboriginal people, and for Aboriginal people to be included in counts to determine electoral representation. This has been the largest affirmative vote in the history of Australia's referendums.

In 1971, Yolngu people at Yirrkala sought an injunction against Nabalco to cease mining on their traditional land. In the resulting historic and controversial Gove land rights case, Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been terra nullius before European settlement, and that no concept of Native title existed in Australian law. Although the Yolngu people were defeated in this action, the effect was to highlight the absurdity of the law, which led first to the Woodward Commission, and then to the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

In 1972, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established on the steps of Parliament House in Canberra, in response to the sentiment among Indigenous Australians that they were "strangers in their own country". A Tent Embassy still exists on the same site.

In 1975, the Whitlam government drafted the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, which aimed to restore traditional lands to indigenous people. After the dismissal of the Whitlam government by the Governor-General, a reduced-scope version of the Act (known as the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976) was introduced by the coalition government led by Malcolm Fraser. While its application was limited to the Northern Territory, it did grant "inalienable" freehold title to some traditional lands.

A 1987 federal government report described the history of the "Aboriginal Homelands Movement" or "Return to Country movement" as "a concerted attempt by Aboriginal people in the 'remote' areas of Australia to leave government settlements, reserves, missions and non-Aboriginal townships and to re-occupy their traditional country."

In 1992, the Australian High Court handed down its decision in the Mabo Case, declaring the previous legal concept of terra nullius to be invalid. This decision legally recognized certain land claims of Indigenous Australians in Australia prior to British Settlement. Legislation was subsequently enacted and later amended to recognize Native Title claims over land in Australia.

In 1998, as the result of an inquiry into the forced removal of Indigenous children (see Stolen generation) from their families, a National Sorry Day was instituted, to acknowledge the wrong that had been done to Indigenous families. Many politicians, from both sides of the house, participated, with the notable exception of the Prime Minister, John Howard.

In 1999 a referendum was held to change the Australian Constitution to include a preamble that, amongst other topics, recognised the occupation of Australia by Indigenous Australians prior to British Settlement. This referendum was defeated, though the recognition of Indigenous Australians in the preamble was not a major issue in the referendum discussion, and the preamble question attracted minor attention compared to the question of becoming a republic.

In 2004, the Australian Government abolished The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), which had been Australia's top Indigenous organiation. The Commonwealth cited corruption and, in particular, made allegations concerning the misuse of public funds by ATSIC's chairman, Geoff Clark, as the principal reason. Indigenous specific programs have been mainstreamed, that is, reintegrated and transferred to departments and agencies serving the general population. The Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination was established within the then Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, and now with the Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs to coordinate a "whole of government" effort.

In June 2005, Richard Frankland, founder of the 'Your Voice' political party, in an open letter to Prime Minister John Howard, advocated that the eighteenth-century conflicts between Indigenous and colonial Australians "be recognised as wars and be given the same attention as the other wars receive within the Australian War Memorial". In its editorial on 20 June 2005, Melbourne newspaper, The Age, said that "Frankland has raised an important question," and asked whether moving "work commemorating Aborigines who lost their lives defending their land ... to the War Memorial [would] change the way we regard Aboriginal history."

In 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a formal apology to the Aboriginal people.

Modern day scientists and others often say that the Australian Aborigines arrived in the continent of Australia, by crossing land bridges or landing on the northern shores by canoes.

Lock of hair pins down early migration of Aborigines BBC - September 22, 2011

A lock of hair has helped scientists to piece together the genome of Australian Aborigines and rewrite the history of human dispersal around the world. DNA from the hair demonstrates that indigenous Aboriginal Australians were the first to separate from other modern humans, around 70,000 years ago. This challenges current theories of a single phase of dispersal from Africa.

Australia discovered by a Southern Route PhysOrg - July 22, 2009

Genetic research indicates that Australian Aborigines initially arrived via south Asia. Researchers found telltale mutations in modern-day Indian populations that are exclusively shared by Aborigines.

Dr Raghavendra Rao worked with a team of researchers from the Anthropological Survey of India to sequence 966 complete mitochondrial DNA genomes from Indian 'relic populations'. He said, "Mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from the mother and so allows us to accurately trace ancestry. We found certain mutations in the DNA sequences of the Indian tribes we sampled that are specific to Australian Aborigines. This shared ancestry suggests that the Aborigine population migrated to Australia via the so-called 'Southern Route'".

The 'Southern Route' dispersal of modern humans suggests movement of a group of hunter-gatherers from the Horn of Africa, across the mouth of the Red Sea into Arabia and southern Asia at least 50 thousand years ago. Subsequently, the modern human populations expanded rapidly along the coastlines of southern Asia, southeastern Asia and Indonesia to arrive in Australia at least 45 thousand years ago. The genetic evidence of this dispersal from the work of Rao and his colleagues is supported by archeological evidence of human occupation in the Lake Mungo area of Australia dated to approximately the same time period.

Discussing the implications of the research, Rao said, "Human evolution is usually understood in terms of millions of years. This direct DNA evidence indicates that the emergence of 'anatomically modern' humans in Africa and the spread of these humans to other parts of the world happened only fifty thousand or so years ago. In this respect, populations in the Indian subcontinent harbor DNA footprints of the earliest expansion out of Africa. Understanding human evolution helps us to understand the biological and cultural expressions of these people, with far reaching implications for human welfare."

To the early Europeans, the Aborigines of the Sydney district (and later those throughout the whole continent), were primitives, natives or Noble Savages. So, descriptions of them (either written or in sketches/ paintings), were classificatory and comparative. There were a number of physical distinctions between different tribes. It was noted that the Gundungurra who lived in the Blue Mountains west of Camden were taller and stronger than the Eora / Dharawal who lived on the coast. Or so European observers said. Some tribespeople were said to be darker than others (dark brown or black) and were different in other ways, but anyone who indulges in descriptions should ask themselves why they are doing this. People are people and differences of color and shape shouldn't matter. However derogatory descriptions of Aborigines during the 19th century were often a justification for massacres and poisoning of people.

Each tribe had their own particular style of spears. Basically, all spears were made from timber or from the stems of plants. They ranged in length from about 1.5 meters to 4 or 5 meters with various forms of points, tips or blades. Some spear tips were prongs which were used to catch fish; others were made from stone flakes while others were made from fish bones and shells. Spears were mainly used for hunting but they were also used in battles.

The Aboriginal people of the Sydney, Illawarra and Shoalhaven district (and most, if not in all parts of Australia), were often observed by early settlers to be naked. The men and women of some tribes are known to have worn a belt around their middle made of hair, animal fur, skin or fiber which they used to carry tools and weapons.

These belts often had a flap at the front, however, this was a modification that was added during European colonization when the British colonists and authorities were concerned about modesty and imposed their standards on the Aborigines - who were unashamed of their nakedness. However, Aboriginal people needed to be warm in winter months and did make cloaks which they made from animal skins e.g.., possum skins. They worn them during the day and used them as blankets during the night. A number of skins were needed to make the garment and they were cleaned, dried and sewn together.

During colonization individual settlers gave the Aborigines their old clothes (known as slops). So the people were often recorded as wearing a variety of clothes such as army or navy jackets, trousers, petticoats and blouses (etc).

From the 1830's a number of Governors issued English blankets to the Aborigines through Magistrates and well respected settlers in various parts of the country. The blankets were not as warm as possums skin cloaks and many Aborigines caught influenza and bronchitis and died from these diseases.

Although there were over 250-300 spoken languages with 600 dialects at the start of European settlement, fewer than 200 of these remain in use - and all but 20 are considered to be endangered.

Before colonization there were between 200 and 250 Aboriginal languages spoken throughout the continent of Australia. In other words the Aborigines did not speak the same or 'one' language. It has also been estimated that there were as many as 600 languages spoken at the time of colonization. However, it has also been said, that there was one language and several dialects.

The 'one language' theory fits with the theory of the migratory origins of the people in the continent. In other words that all Aborigines belong to the one race as descendants of people who came from Asia, Africa and other places across land bridges. Whether this happened or not is speculative. What is certain, is that the Aborigines who belonged to a particular tribe spoke a language that was different to their neighbors. This fact has led to scientists identifying Language or Cultural groups which were comprised of a number of tribes who spoke the same language. It is also certain that some Aboriginal people spoke more than one language and it is interesting to note, that when the Europeans arrived in this country some Aborigines quickly learned to speak English while the Europeans themselves often struggled to speak even a few Aboriginal words.

In 1888 it was said that the language of the Australian Aborigines was "in fullness of tone, variety of sound, and easy flow, is not to be surpassed. In proof of this it is only necessary to refer to the Aboriginal names of the various locations throughout the colonies.

Some Aboriginal words are still used today. For example the word Bundi is the basis for the name Bondi n Sydney's eastern suburbs which has become the most famous beach in the world. Bennelong Point (the site of the Sydney Opera House) is named after Bennelong an Aborigine of the Manly area who was kidnapped by Governor Arthur Philip); Botany Bay was known as Kamay to the Aborigines of the area; Cronulla is based on the word Kurranulla meaning 'pink shell'; Dapto in the Illawarra district is a corruption of the word Dappeto; Dhurawal Bay on the George's River near Liverpool is named after the traditional tribe of the Sydney district the Dharawal also called the Eora.

Aboriginal language had ice age origins News in Science - December 13, 2006

Clendon says the continent, known as Sahul, was relatively densely populated on the land bridge connecting northern Australia to New Guinea, now separated by the Arafura Sea. The other populated area was along what is now Australia's eastern seaboard. The two population groups were separated by a vast, cold, windswept, arid stretch of land that covered most of the continent, says Clendon, who was with the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education when he published the research. The eastern group spoke a tongue that became what is known today as Pama Nyungan and includes languages like Pitjantjatjara, Yolngu and Warlpiri. And the Arafurans spoke another family of languages used in northern Australia today. "What I'm suggesting is that Pama Nyungan and non-Pama Nyungan languages go back about 13,000 years to when there was a land bridge between New Guinea and Australia," he says.

Until now, the reason why these two Aboriginal language groups are so different, each with a distinct grammar and vocabulary, has been a mystery. Climate change - Around 11,000 years ago what was the Arafura plain was flooded by rising seas as the ice age ended. This caused the northern people to migrate into either New Guinea or to northern parts of Australia. Meanwhile, increased rainfall and warmer temperatures made inland parts of the continent more habitable and sparked a westward migration of eastern dwellers. This introduced their language group to more central areas of Australia. Both groups maintained their distinct languages, Clendon says. His hypothesis provides an alternative picture to the traditional view that 6000 years ago a single proto-language spread from the Gulf of Carpentaria around Australia, eventually giving rise to existing Aboriginal languages. "We know about changes in climate and sea levels at the end of the Pleistocene era. I'm suggesting the way languages are configured in Australia today are a result of those changes that happened at the end of the ice age."

Provocative but unconvincing - Writing in a reply to Clendon's article, Professor Nicholas Evans, an expert in Aboriginal languages from the University of Melbourne, describes Clendon's hypothesis as "fresh and provocative". However, he says there are flaws in the argument, including that there is only weak evidence of similarities between southern New Guinea and northern Aboriginal languages. Evans says he remains to be convinced about Clendon's proposal. "But it adds a welcome alternative to a field in which we are still a long way from having any clear picture of the unimaginably long human occupation of Sahul," he says.

Hunting is a word that is used to identify the practice of catching and killing game either as a sport or as a source of food. Gathering is the collecting of food such as plants, berries, eggs or insects. Fishing is another method of obtaining food.The Aborigines who lived in areas which included waterways such as rivers or were on the seacoast, made canoes from bark or tree trunks.

The Eora / Dharawal made canoes which carried up to three or four people for fishing. In other areas, the canoes were much larger and included dugouts and outrigger types. They were made from tree trunks (not just the bark). Aboriginal men and women who lived in coastal regions or in areas where there were rivers, caught and collected food by fishing. Males usually used spears, while females used hand lines with hooks made from shells and rocks as sinkers. Fish species were also caught by the use of fish traps. Some traps were made from rocks in the form of a pen. At high tide fish could swim in and out of them, but some were trapped within the rock walls at low tide. Traps were also constructed from sticks and tree branches across rivers to make a dam. When sufficient numbers were trapped the people would enter the water, scoop up the fish in their hands and throw them onto the river bank to be collected for cooking.

Males hunted animals such as kangaroos, wallabies, echidnas and possums. But also reptiles (snakes and lizards) and birds such as ducks, swans and parrots. They used spears and boomerangs to hit, catch and kill - but also climbed trees to get their food. Sometimes they hunted in parties or groups and each person shared the catch. On these occasions some of the men acted as 'beaters' driving animals towards another group of men who were armed and waiting to spear the animals that were driven towards them. Sometimes they used fire to drive the animals forward.

Aboriginal woman (often carrying babies on their backs) and assisted by young children left the camp on a daily basis searching and collecting berries, yams and other sources of food.

Gathering provided the bulk or main source of food for the Australian Aborigines. It has also been said that some tribes people were mainly 'vegetarians' because 'meat' was not readily available in some areas. It is also a fact that some Aboriginal people ate more marine life (fish, oysters and mussels etc) because these food items were predominant in the area in which they lived.

Survival was highly dependent upon knowledge of the life-cycle of flora and fauna and it is certain that the Aborigines had excellent understanding as they learned to track, hunt and gather food from when they were young children.

In 1972 Australian Anthropologist, Kenneth Maddock said: "Australia is the only continent to have been populated until modern times exclusively by hunters and gatherers..." (The Australian Aborigines. A Portrait of their society). He also quoted statistics showing that in 10,000 BC all human beings (100%) were hunters and gatherers; by 1,500 AD this had reduced to about 1% because mankind had generally developed skills in the cultivation of crops and domestication of animals. By 1960 only 0.001% of the world's population were hunters and gatherers.

The fact that the Aborigines did not cultivate land to grow crops or domesticate animals, they have often been portrayed as being a backward race. However this can be disputed. After all, the Aborigines did harvest crops in the sense that they made a form of flour from various types of flora. Domestication of animals was not possible due to the type (or perhaps kind) of animals that roamed the continent of Australia. For example kangaroos, wombats, possums and snakes.

Sheep and cow were introduced by Europeans. But there is evidence to suggest that the Aborigines of the Cowpastures district (Campbelltown area) herded and killed cattle that had escaped from the Port Jackson area circa 1788 and found there way to that area. These cattle had been transported from Africa and before vandals destroyed it, there was a cave in the Campbelltown area that was called Bull Cave, because of the drawings of cattle on the walls.

Those Aborigines who lived in coastal regions or near waterways caught fish and eels in a number of ways. Males often used a spear but are known to have also built fish-traps by making rectangular areas with rocks, that stood above the water at low tide. This meant that fish could swim into the traps at high tide and were trapped as the tide receded.

In the Illawarra district the Aborigines were often observed barricading (blocking) rivers with tree branches and logs. As fish swam down the river towards the sea they were trapped behind the dam where they were scooped up and thrown onto the shore. The Aborigines also fished from rocks and beaches using hand lines made from plants and hooks made from shells. Stones were used as sinkers.

Aboriginal people had to catch and collect their food, each and every day of their life. They were successful at doing this because they had an intimate knowledge of food-chain cycles, the migration patterns of birds and of the habitat where they lived. No doubt there were times when there were food shortages. But the essential point is that the Aboriginal people had a complete understanding of the flora and fauna within their tribal territory. They also engaged in land management practices - mainly burning grass and weeds.

Their totemic practices protected species because a person could not eat his own totem and others needed permission to catch another person's totem on his land. For example, a man whose totem was a waterfowl would not eat that bird (otherwise it would be a form of cannibalism). Other members of the tribe could not hunt the bird in the territory that belonged to another man. This provided a safe environment for different species.

Aboriginal Australians were social beings who lived in a number of social groups sometimes called bands, clans, sub-tribes and tribes, but essentially in a family or kinship group who were 1) of the same blood-line and 2) were related to other people through totems.

The social groupings of ATSI people meant that their relationships were far more extensive than our own method of identifying people as mother, father, brother, sister and cousins (etc). Aboriginal relationships are difficult to understand but the relationships of an Aboriginal male child are detailed in following script (with western ones shown in brackets), to give some idea of them: The family was usually comprised of father's father (grandfather) and often his brother or brothers who was / were known also known as father's father (no western equivalent); his wife or wives (grandmother); a father (father) and perhaps his brothers (uncles) who was also considered to be an Aboriginal male child's father.

Each family group had a headman or Elder who was the leader of the unit. He decided when to move camp and settled disputes

Food such as oysters, mussels and pippies were enjoyed. Sometimes they cooked them on the ashes of a fire and the Sydney Aborigines are known to have taken a fire with them aboard their canoes when they went fishing. This meant they could cook and eat their catch as they continued catching fish. They also took some of their catch back to the camp to share with others, but eating food while catching it gave them the energy to collect sufficient quantity for others.

Animals, birds and reptiles were also caught and cooked on an open fire. However they 'scorched' rather than cooked these foods. In other words, they did not roast the joint of a kangaroo like Europeans do today. For example by placing a leg of lamb in an oven for an hour or two. The Aborigines simply singed the food to remove feathers, scales and fur and ate partly cooked meat.

Other sources of food included yams (sweet potatoes), berries and intestines such as liver (yuck). But they generally hunted and collected the wide variety of food that was available in the places in which they lived.

One food that was cooked by the Aborigines was a type of bread which was also popular among early European settlers who called it damper. This is made by grinding seeds into flour, mixing this with water into a doughy paste and cooking it in the ashes of a warm fire.

The Aborigines lived within a tribal territory where they obtained their daily food needs. Some tribes lived in desert country, while others lived in mountain, coastal or timbered areas. This meant that the members of different tribes ate different foods. It also meant that some of them were constantly on the move hunting and gathering. Others lived a semi-nomadic life in areas where there were amply food supplies.

The Eora / Dharawal people who lived on the coastal area between the Hawkesbury River and the Shoalhaven River were hunters and gatherers of fish, shellfish, plants and animals. They caught fish such as bream, groper, snapper and whiting; collected shellfish including oysters (rock and mud), cockles and conniwink.

Plant foods included: native cherries, the cabbage palm, water lilies, five-corners and pigface. Animals, birds and reptiles such as kangaroos, ducks and snakes were also hunted for consumption purposes.

Every tribe in Australia was divided into a number of small social groups, but for marriage purposes, into two main groups sometimes called marriage moieties. People didn't marry outside of their group. Marriage arrangements were made when children were very young and sometimes before they were born.

Aboriginal people were social beings as they lived and gathered together in family groups . Their camps were comprised of a number of gunyas (bark huts), but the people also lived in caves or in the open air. Some camps were comprised of as few as 6 to 10 people while in others there were up to 400 people. No doubt the availability of food was a factor in the size of a camp. Each day, various members of the group would leave the camp to hunt and gather food and return to the camp to share the catch with others.

During the 1830s William Govett (surveyor), visited a camp and recorded (in Sketches of New South Wales), that the people usually settled in their camp as night fell and were engaged in a number of activities - normal family life - sharing stories about the happenings of the day, repairing weapons, singing songs and playing games etc. Govett described a young man in one gunya using double sets of strings to make diamonds, squares, circles and other shapes. He also told of an adult amusing a young child by placing a leaf on the back of his left hand, striking it with his finger causing the leaf to ascend perpendicularly to the squeals of delight from the child.

Aboriginal people lived in family groups. The Elder or Elders gunyah (hut) were situated in the center of the camp and others spanned out in circles around the central hut. However, the people often slept in the open and in caves, so it is likely that the Elder decided where he wanted to sleep with his wife or wives and everyone one else spread-out from the spot he had chosen. No doubt some people were more important than others and the most important ones camped near the Elders.

The affinity of attachment to a particular area of land by the Aborigines was based on their Dreamtime beliefs, that the land had been created for them by ancestral heroes and heroines. Every rock, tree and waterhole; every animal, bird and insect; the sky above and all it contained were believed to have been created in the Dreamtime.

At some indefinite time the creators disappeared, however, many were believed to have remained in secret places in the land - in rivers, caves and other places. In other words, the Aborigines believed that their land had been created by spirits who continued to live in the land.

This was a superstitious belief, but it was very important to the Aborigines. For example, there were never any wars of conquest between Aboriginal tribes. They were too superstitious to do this and living in the land of another tribe would have involved them in living among strange and no doubt hostile spirits.

Land was spiritual, but also an economic resource as it provided the people with food, sources of wood, fiber and glue for making spears, utensils and other implements. However the people respected these aspects of their land and were environmentalists in the sense of 'taking care' of the land through their practices of performing increase ceremonies, singing 'Songlines' and relationships with flora and fauna through a system of totemic relationships.

Traditional Aboriginal people (before their society was changed with the arrival of the British into their lands), lived in relatively small groups which have been called clans, bands, family groups, sub-tribes and by a variety of other names.

The larger (well known term) social unit known as a tribe, was made up of a number of smaller social units (clans and bands etc). Maybe we can explain it this way: A clan was a family group made up of a grandfather and his wife or wives, his sons and their wife or wives and their children. A number of these groups formed a tribe. The exact number of clans which comprised a tribe cannot be said precisely, as this varied. However in the Sydney district it is known that in 1788 there were at least 30 clans of the Eora / Dharawal tribe. Each clan had a name for themselves based on the name in their language for the area they lived in. For example the men of Cadi were known as the Cadigal (Cadjigal) females added the postfix eean so the women from Cadi were the Cadieean and they lived around South Head, Elizabeth Bay, Rushcutters Bay to present day Circular Quay. The Gweagal / Gweaeean lived at Kurnell. The clans that formed a tribe were those who believed in the same Dreamtime creation stories, spoke the same language and celebrated the same customs such as initiation rites.

Culture is a celebration of beliefs and usually (if not always) includes rites of passage from one stage of life to another. Culture is stories and songs.

Particularly because their stories and songs informed them about creation, the relationship between mankind and nature and were the source of their tribal laws. The tradition of initiation was an expression of Aboriginal culture and was carried out for thousands of years in exactly the way that had been ordered by the ancestors in the Dreamtime. On another level the stories and songs were believed to be important for the preservation and conservation of their land and all it contained. This involved singing Songlines that had been sung by the ancestors and the concept of taking care.

Until 1788 the Aborigines of Australia lived and celebrated a culture that was basically unchanged for thousands of years. Each tribe had their own beliefs - their own songs and stories, but until colonization, they were the oldest surviving race in the entire world. They existed as a race of people well before the Egyptians were building the pyramids, while the Greeks were constructing the Pantheon and while Britain was ruled by the Roman Empire. However the first Europeans to arrive in the continent considered the 'natives' to be primitives. This was largely due to a lack of understanding about the culture of the Aborigines.

A cultural group was comprised of two or more tribes that associated with each other for cultural purposes. For example to celebrate corroborees, barter or exchange goods, conduct initiation ceremonies or intermarry.

On the Far South Coast of New South Wales early records show that members of the Yuin tribe often associated with those from the Canberra area. These tribes did not associate with the Dharawal tribe of the Shoalhaven, Illawarra and Sydney districts, who gathered from time to time with the Gundungurra of the Goulburn and Camden area.

The Australian Aboriginal flag was originally designed as a protest flag for the land rights movement of Indigenous Australians but has since become a symbol of the Aboriginal people of Australia. The flag is a yellow disc on a horizontally divided field of black and red. It was designed in 1971 by Harold Thomas, an Aboriginal artist descended from the Luritja of Central Australia. On 14 July 1995, both the Aboriginal flag and the Torres Strait Islander Flag were officially proclaimed by the Australian government as "Flags of Australia" under Section 5 of the Flags Act 1953.

The flag was first flown on National Aborigines' Day in Victoria Square in Adelaide on 12 July 1971. It was also used in Canberra at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy from late 1972. In the early months of the embassy-which was established in February that year - other designs were used, including a black, green and red flag made by supporters of the South Sydney Rabbitohs rugby league club, and a flag with a red-black field containing a spear and four crescents in yellow.

Cathy Freeman caused controversy at the 1994 Commonwealth Games by waving both the Aboriginal flag and Australian national flag during her victory lap of the arena, after winning the 200 metres sprint; only the national flag is meant to be displayed. Despite strong criticism from both Games officials and the Australian team president Arthur Tunstall, Freeman flew both flags again after winning the 400 metres.

The decision (by Prime Minister Paul Keating) to make the Aboriginal flag a national flag was opposed by the Liberal Opposition at the time, with John Howard making a statement on 4 July 1995 that "any attempt to give the flags official status under the Flags Act would rightly be seen by many in the community not as an act of reconciliation but as a divisive gesture." However since Howard took office in 1996, the flag has remained a national flag. This decision was also criticised by Thomas himself, who said the flag "doesn't need any more recognition"

In 1997 the Federal Court of Australia declared that Harold Thomas was the owner of copyright in the design of the Australian Aboriginal flag, and thus the flag has protection under Australian copyright law. Thomas had sought legal recognition of his ownership and compensation following the Federal Government's 1995 proclamation of the design. His claim was contested by two others, Mr. Brown and Mr. Tennant. Since then, Thomas has awarded rights solely to Carroll and Richardson Flags for the manufacture and marketing of the flag.

The National Indigenous Advisory Committee campaigned for the Aboriginal flag to be flown at Stadium Australia during the 2000 Summer Olympics.[5] SOCOG announced that the Aboriginal flag would be flown at Olympic venues. The flag was flown over the Sydney Harbour Bridge during the march for reconciliation of 2000, and many other events.

On the 30th anniversary of the flag in 2001, thousands of people were involved in a ceremony where the flag was carried from the Parliament of South Australia to Victoria Square. Since 8 July 2002, after recommendations of the Council's Reconciliation Committee, the Aboriginal Flag has been permanently flown in Victoria Square and the front of the Town Hall.

In Aboriginal society every person (particular every initiated male) was considered to be equal. No one had authority over anyone else in the sense of ruling them, but this is not to say that there weren't leaders. There are always leaders in any society - people who have personal qualities that others admire. But there were no elected leaders in Aboriginal society. There were also people who performed particular roles. For example clever men also known as Koradjis and as Doctors by Europeans, had or acquired special skills and were considered to be authorities on certain matters.

There were leaders known as Elders. People whom others listened to, asked for advice and generally obeyed when they issued orders. The Elders were considered to be wise in knowledge of the Dreamtime the law and the lore's of the tribe. An Elder was usually a male but gray hair and old age were not the only criteria to be an Elders. In fact some elderly people were not considered to be Elders.

To understand the role of the Elders it is necessary to understand that the Aborigines lived in small family groups also known as clans, bands and sub-tribes. Within the immediate family groups, the eldest males and females were treated with respect and acknowledged as leaders in the sense that they made decisions about the family. For example they settled disputes and decided when the group would move camp to another area. When a number of blood-line families lived together it is likely that the Elder of the group was the person considered by the members to be the wisest of the older people.

In large groups which may have been comprised of several hundred people, a number of Elders met to make decisions on behalf of the group. This has become known as an Elder's Council, but it wasn't a council in the sense of being a form of government. Instead such councils met for the purpose of conducting initiation, marriage and burial ceremonies