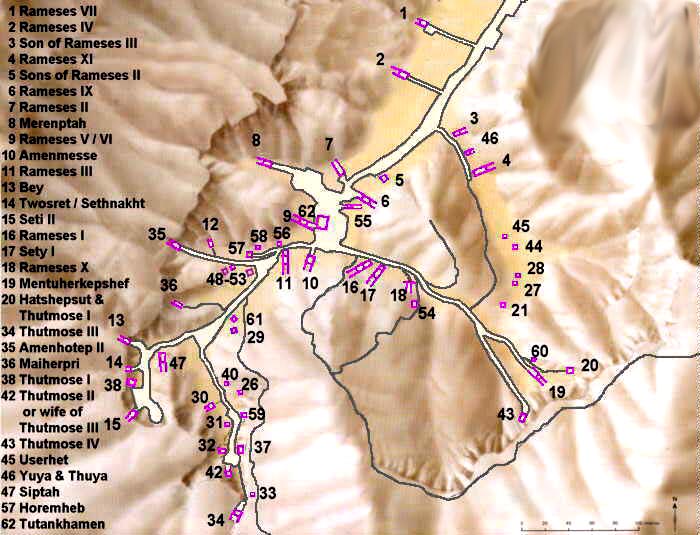

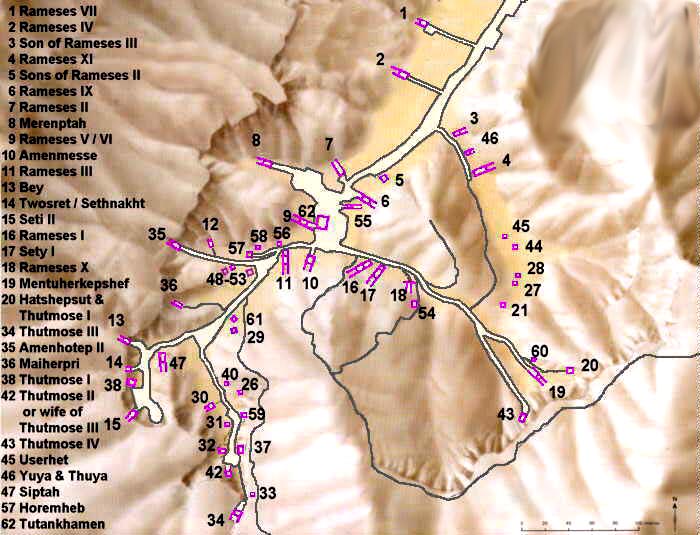

�The Valley of the Kings is a valley in Egypt where for a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th century BC, tombs were constructed for the kings and powerful nobles of the New Kingdom (the Eighteenth through Twentieth Dynasties of Ancient Egypt). The valley stands on the west bank of the Nile, across from Thebes (modern Luxor), within the heart of the Theban Necropolis. The wadi consists of two valleys, East Valley (where the majority of the royal tombs situated) and West Valley.

The area has been a focus of concentrated archaeological and egyptological exploration since the end of the eighteenth century, and its tombs and burials continue to stimulate research and interest. In modern times the valley has become famous for the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun (with its rumours of the Curse of the Pharaohs), and is one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world. In 1979, it became a World Heritage Site, along with the rest of the Theban Necropolis.

The Valley was used for primary burials from approximately 1539 BC to 1075 BC, and contains some 60 tombs, starting with Thutmose I and ending with Ramesses X or XI.

The Valley of the Kings also had tombs for the favourite nobles and the wives and children of both the nobles and pharaohs. Around the time of Ramesses I (ca. 1300 BC) the Valley of the Queens was begun, although some wives were still buried with their husbands.

The quality of the rock in the Valley is very inconsistent. Tombs were built, by cutting through various layers of limestone, each with its own quality. This poses problems for modern day conservators, as it must have to the original architects. Building plans were probably changed on account of this. The most serious problem are the shale layers. This fine material expands when it comes into contact with water. This has damaged many tombs, particularly during floods.

The Valley of the Kings, in Upper Egypt, Thebes, the burial place of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom.

Most of the tombs were cut into the limestone following a similar pattern: three corridors, an antechamber and a sunken sarcophagus chamber. These catacombs were harder to rob and were more easily concealed. The switch to burying the pharaohs within the valley instead of pyramids, was intended to safeguard against tomb robbers. In most cases this did not prove to be affective. Many of the bodies, of the pharaohs, where moved by the Egyptian priests, and placed in several caches, during the political upheaval of the 21st Dynasty.

Construction of a tomb usually lasted six years, beginning with each new reign.

The Valley of the Kings has two components - the East Valley and the West Valley. It is the East Valley which most tourists visit and in which most of the tombs of the New Kingdom Pharaohs can be found.

By the end of the New Kingdom, Egypt had entered a long period of political and economic decline. The priests at Thebes grew in power and effectively administered Upper Egypt, while kings ruling from Tanis controlled Lower Egypt. The Valley began to be heavily plundered, so the priests of Amen during 21st Dynasty to open most of the tombs and move the mummies into three tombs in order to better protect them. Later most of these were moved to a single cache near Deir el-Bari. During the later Third Intermediate Period and later intrusive burials were introduced into many of the open tombs.

Almost all of the tombs have been ransacked, including Tutankhamun's, though in his case, it seems that the robbers were interrupted, so very little was removed.The valley was surrounded by steep cliffs and heavily guarded. In 1090 BC, or the year of the Hyena, there was a collapse in Egypt's economy leading to the emergence of tomb robbers. Because of this, it was also the last year that the valley was used for burial. The valley also seems to have suffered an official plundering during the virtual civil war which started in the reign of Ramesses XI. The tombs were opened, all the valuables removed, and the mummies collected into two large caches. One, the so-called Deir el-Bahri cache, contained no less than forty royal mummies and their coffins; the other, in the tomb of Amenhotep II, contained a further sixteen.

The Valley of the Kings has been a major area of modern Egyptological exploration for the last two centuries. Before this the area was a site for tourism in antiquity (especially during Roman times). This areas illustrates the changes in the study of ancient Egypt, starting as antiquity hunting, and ending as scientific excavation of the whole Theban Necropolis. Despite the exploration and investigation noted below, only eleven of the tombs have actually been completely recorded.

The Greek writers Strabo and Diodorus Siculus were able to report that the total number of Theban royal tombs was 47, of which at the time only 17 were believed to be undestroyed. Pausanias and others wrote of the pipe-like corridors of the Valley - i.e. the tombs.

Clearly others also visited the valley in these times, as many of the tombs have graffiti written by these ancient toursits. Jules Baillet located over 2000 Greek and Latin graffiti, along with a smaller number in Phoenician, Cypriot, Lycian, Coptic, and other languages.

Before the nineteenth century, travel from Europe to Thebes (and indeed anywhere in Egypt) was difficult, time-consuming and expensive, and only the hardiest of European travelers visited Š before the travels of Father Claude Sicard in 1726, it was unclear just where Thebes really was. It was known to be on the Nile, but it was often confused with Memphis and several other sites. One of the first travelers to record what he saw at Thebes was Frederic Louis Norden, a Danish adventurer and artist. He was followed by Richard Pococke, who published the first modern map of the valley itself, in 1743.

In 1799, Napoleon's expedition drew maps and plans of the known tombs, and for the first time noted the Western Valley (where Prosper Jollois and edouard de Villiers du Terrage located the tomb of Amenhotep III, WV22). The Description de l'Egypte contains two volumes (out a total of 19) on the area around Thebes.

European exploration continued in the area around Thebes during the Nineteenth Century, boosted by Champollion's translation of hieroglyphs early in the century. Early in the century, the area was visited by Belzoni, working for Henry Salt, who discovered several tombs, including that of those of Ay in the West Valley (WV23) in 1816, and Seti I, KV17 the next year. At the end of his visits, Belzoni declared that all of the tombs had been found and nothing of note remained to be found.

In 1827 John Gardiner Wilkinson was assigned to paint the entry of every tomb, giving them each a designation that is still in use today Š they were numbered from KV1 to KV21 (although the maps show 28 entrances, some of which were unexplored). These paintings and maps were later published in The Topography of Thebes and General Survey of Egypt, in 1830. At the same time James Burton explored the valley. His works included making KV17 safer from flooding, but he is more well known for entering KV5.

In 1829, Champollion himself visited the valley, along with Ippolitio Rosellini. The expedition spend 2 months studying the open tombs, visiting about 16 of them. The copied the enscriptions and identfied the original tomb owners. In the tomb of KV17, they removed some wall decorations, which are now on dispaly in the Louvre, Paris.

In 1845 - 1846 the valley was explored by Carl Richard Lepsius' expedition, they explored and documented 25 main valley and 4 in the west.The later half of the century saw a more concerted effort to preserve rather than simply gathering antiquities. Auguste Mariette's Egyptian Antiqities Service started to explore the valley, first with Eugene Lefebre in 1883, then Jules Balliet and George Benedite in early 1888 and finally Victor Loret in 1898 to 1899. During this time George Daressy explored KV9 and KV6.

Loret added a further 16 tombs to the list of tombs, and explored several tombs that had already been discovered.

When Gaston Maspero was reappointed to head the Egyptian Antiquities Service, the nature of the exploration of the valley changed again, Maspero appointed Howard Carter as the Chief Inspector of Upper Egypt, and the young man discovered several new tombs and explored several others, clearing KV42 and KV20.

Around the turn of the Twentieth Century, the American Theodore Davis had the excavation permit in the valley, and his team (led mosty by Edward R. Ayrton) discovered several royal and non-royal tombs (KV43, KV46 & KV57 being the most important). In 1907 they discovered the possible Amarna Period cache in KV55. After finding what they thought was the burial of Tutankhamun (KV61), it was announced that the valley was completely explored and no further burials were to be found.

Howard Carter then acquired the right to explore the valley and after a systematic search discovered the actual tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) in November 1922.

At end of the century, the Theban Mapping Project re-discovered and explored tomb KV55, which has since be discovered to be probably the largest in the valley, and was either a cenotaph or real burial for the sons of Ramesses II. Elsewhere in the eastern and western branches of the valley several other expeditions cleared and studied other tombs. Recently the Amarna Royal Tombs Project has been exploring the area around KV55 and KV62, the Amarna Period tombs in the main valley.

Various expeditions have continued to explore the valley, adding greatly to the knowledge of the area. In 2001 the Theban Mapping Project designed new signs for the tombs, providing information and plans of the open tombs. A new visitors' centre is currently being planned. On February 8, 2006, American archaeologists uncovered a pharaonic-era tomb (KV63), the first uncovered there since King Tutankhamun's in 1922. The 18th Dynasty tomb included five mummies in intact sarcophagi with coloured funerary masks along with more than 20 large storage jars, sealed with pharaonic seals.

Mummy Mystery: Tombs Still Hidden in Valley of Kings Live Science - December 4, 2013

Multiple tombs lay hidden in Egypt's Valley of the Kings, where royalty were buried more than 3,000 years ago, awaiting discovery, say researchers working on the most extensive exploration of the area in nearly a century. The hidden treasure may include several small tombs, with the possibility of a big-time tomb holding a royal individual, the archaeologists say. Egyptian archaeologists excavated the valley, where royalty were buried during the New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C.), between 2007 and 2010 and worked with the Glen Dash Foundation for Archaeological Research to conduct ground- penetrating radar studies.

Ancient Flowers Found in Egypt Coffin in Egypt's Valley of the Kings "KV 63" National Geographic - June 30, 2006

The last of eight sarcophagi from a recently discovered burial chamber in Egypt's Valley of the Kings revealed ancient garlands of flowers. The coffin contained strips of fabric and woven laurels of delicate dehydrated flowers.

The flowers are likely the remains of garlands strung with gold strips that were worn by ancient Egyptian royalty.

It's very rare, there's nothing like it in any museum.

Pharaonic tomb find stuns Egypt

BBC - February 10, 2006

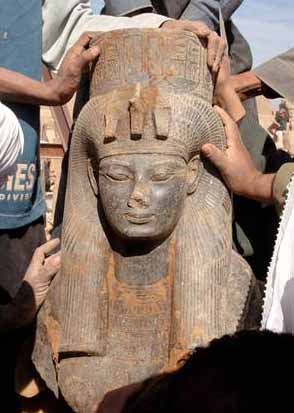

Researchers discover 3,400-year-old artifact depicting Queen Ti MSNBC - January 25, 2006

Egyptologists have discovered a statue of Queen Ti, wife of one of EgyptÕs greatest pharaohs and grandmother to the boy-king Tutankhamun, at an ancient temple in Luxor, an Egyptian antiquities official said. The roughly 3,400-year-old statue was well-preserved. Ti's husband, Amenhotep III, presided over an era which saw a renaissance in Egyptian art. A number of cartouches, or royal name signs, of Amenhotep III were found on the statue, and the statue's design and features allowed researchers to identify it as a New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty statue of Queen Ti.

Akhenaten was the son of Amenhotep III and

Queen Tiy, a descendent of a Hebrew tribe.

Queen Tiy wearing a double feathered crown

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS