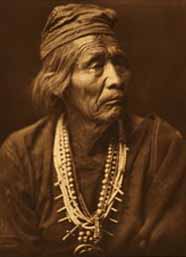

The Navajo, who call themselves Dine ("The People"), are the largest Native American group in North America. Their tales of emergence and migration are similar to other Southwestern tribes such as the Hopi (with whom they have a long running rivalry). Navajo ceremonies such as the Nightway and the Mountain Chant are renowned for their beautiful liturgy.

The Navajo are the largest single federally recognized tribe of the United States of America. The Navajo Nation has 300,048 enrolled tribal members. The Navajo Nation constitutes an independent governmental body which manages the Navajo Indian reservation in the Four Corners area of the United States. The Navajo language is spoken throughout the region, although most Navajo speak English as well.

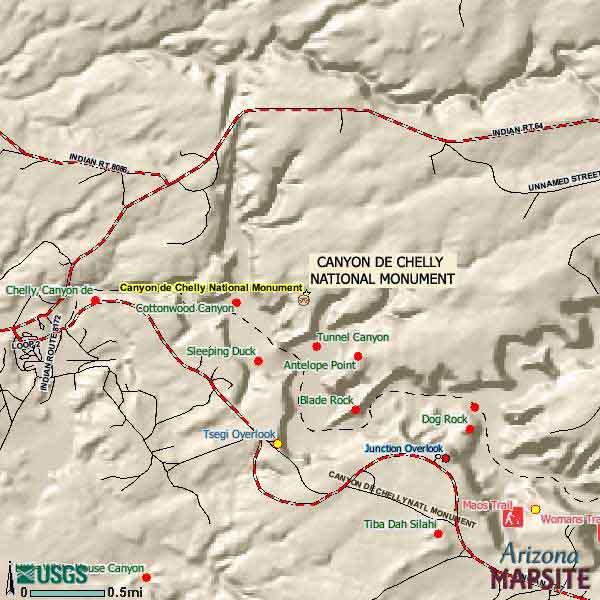

The Nation's boundaries about the Ute Nation at the Four Corners Monument landmark and stretch across the Colorado Plateau into Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. Located within the Navajo Nation are Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Monument Valley, Rainbow Bridge National Monument, the Hopi Indian Reservation, and the Shiprock landmark. The seat of government is located at the town of Window Rock, Arizona.

Members of the nation are often known as Navajo, also spelled Navaho. Navajo call themselves Diné, a term from the Navajo language that means people. The Navajo are closely related to the Apache, and the Navajo language along with other Apache languages make up the Southern Athabaskan language family.

Congress established a Hopi reservation within the Navajo Nation's reservation at an historic homeland where Hopi history predates that of Dine in the area.A conflict over shared lands emerged in the 1980s when the Department of the Interior attempted to relocate Diné living in the Navajo/Hopi Joint Use Area. The conflict was resolved, or at least forestalled, by the award of a seventy-five-year lease to Diné who refused to leave the former shared lands.

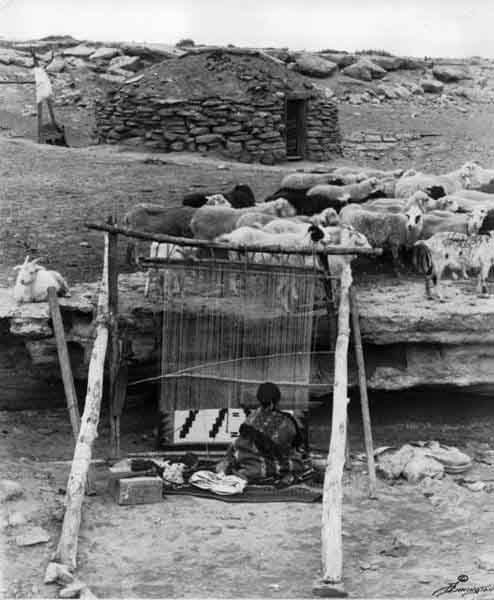

Until they came into contact with the Spanish and Pueblos, the Navajo were hunters and gatherers. They adopted farming techniques and crops from the Pueblo people, growing mainly corn, beans, and squash. As a result of Spanish influence, they began herding sheep and goats, depending on them for food and trade. They spun and wove sheared wool into blankets and clothing which could be used for personal use or trading. They also depended on their flocks of sheep for meat. Their lives depended on sheep so much that, to the Navajo, sheep were a kind of currency and the size of the herd was a mark of social status.

The Navajo speak dialects of the language family referred to as Athabaskan. The Navajo and Apache are believed to have migrated from northwestern Canada and eastern Alaska, where the majority of Athabaskan speakers reside. The Dene First Nations, who live near from Tadoule Lake in Manitoba to the Great Slave Lake in Northwest Territories, also speak Athabaskan languages. Despite the time elapsed, these people reportedly can still understand the language of their distant cousins the Navajo. Archaeological and historical evidence suggests that the Athabaskan ancestors of the Navajo and Apache entered the Southwest by 1400 CE. Navajo oral traditions are said to retain references of this migration.

Navajo oral history also seems to indicate a long relationship with Pueblo people and a willingness to adapt foreign ideas into their own culture. Trade between the long-established Pueblo peoples and the Athabaskans was important to both groups. The Spanish records say by the mid-16th century, the Pueblos exchanged maize and woven cotton goods for bison meat, hides and material for stone tools from Athabaskans who either traveled to them or lived around them. In the 18th century, the Spanish reported that the Navajo had large numbers of livestock and large areas of crops. The Navajo probably adapted many Pueblo ideas into their own different culture.

The Spanish first used the term Apachu de Nabajo in the 1620s to refer to the people in the Chama Valley region east of the San Juan River and northwest of present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico.

By the 1640s, they were using "Navajo" for these indigenous people. The Spanish recorded in 1670s that they lived in a region called Dinetah, about sixty miles (100 km) west of the Rio Chama valley region.

In the 1780s, the Spanish sent military expeditions against the Navajo in the southwest and west of that area, in the Mount Taylor and Chuska Mountain regions of New Mexico.

In the last 1,000 years, Navajos have had a history of expanding their range and refining their self-identity and their significance to other groups. This probably resulted from a cultural combination of endemic warfare (raids) and commerce with the Pueblo, Apache, Ute, Comanche and Spanish peoples, set in the changing natural environment of the Southwest.

The Spanish started to establish a military force along the Rio Grande in the 17th century to the east of Dinetah (the Navajo homeland). Spanish records indicate that Apachean groups allied themselves with the Pueblos over the next 21 years, successfully pushing the Spaniards out of this area following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Raiding and trading were part of traditional Apache and Navajo culture, and these activities increased following the introduction of the horse by the Spaniards, which increased the efficiency and frequency of raiding expeditions. The Spanish established a series of forts that protected new Spanish settlements and also separated the Pueblos from the Apaches.

In the 18th century, Spanish-Navajo relations were improved for 50 years, the constant incursions of Yutas and Comanches against Navajo. The Spaniards - and later, Mexicans - recorded what are called punitive expeditions among the Navajo that also took livestock and human captives.

In 1772, King Charles III of Spain issued a reglamento for the northern frontier of New Mexico, declaring that the main objective of any military operation against the Indians was to get peace and that the death penalty would apply to anyone who killed an Indian prisoner. Non-neutral Navajo tribes or groups in turn raided settlements far away in a similar manner. This pattern continued, with the Athabaskan groups apparently growing to be more formidable foes through the 1840s until the United States Army arrived in the area.

Officially, the Navajos first came in contact with forces of the United States of America in 1846, when General Stephen W. Kearny invaded Santa Fe with 1,600 men during the Mexican American War. In 1846, following an invitation from a small party of American soldiers under the command of Captain John Reid who journeyed deep into Navajo country and contacted him, Narbona and other Navajos negotiated a treaty of peace with Colonel Alexander Doniphan on November 21, 1846, at Bear Springs, Ojo del Oso (later the site of Fort Wingate). The treaty was not honored by young Navajo raiders who continued to steal stock from New Mexican villages and herders. New Mexicans, on their part, together with Utes, continued to raid Navajo country stealing stock and taking women and children for sale as slaves.

In 1849, the military governor of New Mexico, Colonel John Macrae Washington – accompanied by John S. Calhoun, Indian agent – led a force of 400 into Navajo country, penetrating Canyon de Chelly, and there signed a treaty with two Navajo leaders who held themselves out as "Head Chief" and "Second Chief" acknowledging the jurisdiction of the United States and allowing forts and trading posts in Navajo land. The United States, on its part, promised "such donations and such other liberal and humane measures, as it may deem meet and proper". Narbona had been killed along the way in an unhappy accident.

In the next 10 years, the U.S. established forts in traditional Navajo territory. Military records state this was to protect citizens and Navajo from each other. However, the old Spanish/Mexican-Navajo pattern of raids and expeditions against one another continued. New Mexican (citizen and militia) raids increased rapidly in 1860-61, earning it the Navajo name Naahondzood, "the fearing time."

In 1861 Brigadier-General James H. Carleton, the new commander of the Federal District of New Mexico, initiated a series of military actions against the Navajo. Colonel Kit Carson was ordered by Carleton to conduct an expedition into Navajo land and receive their surrender on July 20, 1863. A few Navajo surrendered. Carson was joined by a large group of New Mexican militia volunteer citizens and these forces moved through Navajo land, killing Navajos and destroying any Navajo crops, livestock or dwellings they came across. Facing starvation, Navajo groups started to surrender in what is known as The Long Walk.

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, refers to the 1864 deportation of the Navajo people by the U.S. Government. Navajos were forced to walk at gunpoint from their reservation in what is now Arizona to eastern New Mexico. The trip lasted about 18 days. Sometimes the term "Long Walk" includes all the time the Navajo were away from the land of their ancestors, who had arrived there in the 16th century, according to western anthropologists.

The United States military continued to maintain the forts. Some Navajo were employed by the military as "Indian Scouts" through 1895. Manuelito founded the Navajo Tribal Police, which operated between 1872 and 1875 and was used by the Navajo to stop raiders from their tribe.

By treaty, the Navajo were allowed to leave the reservation with permission to trade. Raiding by the Navajo stopped when they were able to increase the size of their livestock and crops, and not have to risk losing them to others. But, while the size of the reservation increased from 3.5 million acres (14,000 km) to the 16 million acres (65,000 km) of today, economic conflicts with the non-Navajo continued. Civilians and companies raided resources that had been assigned to the Navajo. The US government made leases for livestock grazing, took land for railroads, and permitted mining on Navajo land without consultation with the tribe.

Regional newspapers have many accounts of conflicts between Navajo and European Americans in this period, which regional politicians sometimes turned to their own purposes. While it is likely true that some Navajo strayed, it is equally true that some white citizens strayed from the laws of the land. US military reports did not reflect the alarm of the newspapers.

In 1883, Lt. Parker, accompanied by 10 enlisted men and two scouts, went up the San Juan River to separate Navajos and citizens who had encroached on Navajo land. In the same year, Lt. Lockett, with the aid of 42 enlisted soldiers, was joined by Lt. Holomon at Navajo Springs. Evidently, citizens of the surname(s) Houck and/or Owens had murdered a Navajo chief's son and 100 armed Navajos were looking for them.

In 1887, citizens Palmer, Lockhart, and King fabricated a charge of horse stealing and randomly attacked a home on the reservation. Two Navajo men and all three whites died, but a woman and a child survived. Capt Kerr (with two Navajo scouts) examined the ground and then met with several hundred Navajo at Houcks Tank. Rancher Bennett, whose horse was allegedly stolen, pointed out to Kerr that his horses were stolen by the three whites to catch a horse thief.

In the same year, Lt. Scott went to the San Juan River with two scouts and 21 enlisted men. The Navajo believed Lt. Scott was there to drive off the whites who had settled on the reservation and had fenced off the river from the Navajo. Scott found evidence of many non-Navajo ranches. Only three were active, and the owners wanted payment for their improvements before leaving. Scott ejected them.

In 1890, a local rancher refused to pay the Navajo a fine of livestock. The Navajos tried to collect it, and whites in southern Colorado and Utah claimed that 9,000 of the Navajo people were on a warpath. A small military detachment out of Fort Wingate restored white citizens to order.

In 1913, an Indian agent ordered a Navajo and his three wives to come in, and then arrested them for having a plural marriage. A small group of Navajo used force to free the women and retreated to Beautiful Mountain with 30 or 40 sympathizers. They refused to surrender to the agent, and local law enforcement and military refused the agent's request for an armed engagement. General Scott arrived, and with the help of Henry Chee Dodge, defused the situation.

In the 1930s, the United States government claimed the Navajo's livestock were overgrazing the land. It killed more than 80% of the livestock, in what is known as the Navajo Livestock Reduction, and started a permit system, requiring the Navajo to apply for grazing permits.

Some Americans were strongly sympathetic to the Navajo. In 1937, Mary Cabot Wheelright and Hastiin Klah, an esteemed and influential Navajo singer, or medicine man, founded The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. It is a repository for sound recordings, manuscripts, paintings, and sandpainting tapestries (see below) of the Navajo people. It also featured exhibits to express the beauty, dignity, and logic of Navajo religion.

When Klah met Cabot in 1921, he had witnessed decades of efforts by the US government and missionaries to assimilate the Navajo people into mainstream society. Children were sent away to Indian boarding schools, where they were to learn English and practice Christianity. They were prohibited from using their own languages and religion. The museum was founded to preserve the religion and traditions of the Navajo people, which Klah was sure would soon be lost forever.

In the 1940s, during World War II, the United States denied the Navajo welfare relief because of the Navajos’ communal society. Eventually, in December 1947, the Navajos were provided relief in the post-war period to relieve the hunger that they had had to endure for many years.

In the 1940s, large quantities of uranium were discovered in Navajo land. From then into the early twenty-first century, the US allowed mining without sufficient environmental protection for workers, waterways and land. The Navajo have claimed high rates of death and illness from lung disease and cancer resulting from environmental contamination. Since the 1970s, legislation has helped to regulate the industry and reduce the toll, but the government has not offered holistic and comprehensive compensation is yet forthcoming.

On a tan background the outline of the present reservation is shown in a copper color with the orginial 1868 treaty reservation in dark brown. At the cardinal points in the tan field are the Four Sacred Mountains, as described for the Great Seal. A rainbow, symbol of Navajo sovereignty, spreads over the reservation and the Sacred Mountains.

In the Center of the reservation is a circular symbol depicts the sun above two green stalks of corn between which are three animals representing the Navajo livestock economy, and a traditional hogan and the more modern house. Between the hogan and house is an oil derrick symbolizing the resource potential of the Navajoland, and above this are the wild fauna of the reservation. At the top nearest the sun the modern sawmill symbolizes the progress and industry currently a characteristics of the Navajo Nation.

Dine Bahane' (Navajo: "Story of the People"), the Navajo creation story, describes the prehistoric emergence of the Navajos, and centers on the area known as the Dinetah, the traditional homeland of the Navajo people. This story forms the basis for the traditional Navajo way of life.

The basic outline of Dine Bahane' begins with the Nilch'i Diyin (Holy Wind) being created, the mists of lights which arose through the darkness to animate and bring purpose to the myriad Diyin Dine'e (Holy People), supernatural and sacred in the different three lower worlds. All these things were spiritually created in the time before the earth existed and the physical aspect of humans did not exist yet, but the spiritual did.

They journeyed to the Second World, Ni' Hodootl'izh, which was inhabited by various blue-gray furred mammals and various birds, including blue swallows. The beings from the First World offended Swallow Chief, Tashchozhii, and they were asked to leave. First Man created a wand of jet and other materials to allow the people to walk upon it up into the next world through an opening in the south.

In the Third World, Ni' Haltsooi there were two rivers that formed a cross and the Sacred Mountains but there was still no sun. More animal people lived here too. This time it was not discord among the people that drove them away but a great flood caused by Teehooltsodii when Coyote stole her child.

When the people arrived in The Fourth World, Ni' Hodisxos, it was covered in water and there were monsters (naayee') living here. The Sacred Mountains were re-formed from soil taken from the original mountains in the Second World. First Man, First Woman, and the Holy People created the sun, moon, seasons, and stars. It was here that true death came into existence via Coyote tossing a stone into a lake and declaring that if it sank then the dead would go back to the previous world.

The first human born in the Fourth World is Asdzaa Nadleehe who, in turn, gives birth to the Hero Twins called Naayee' Neizghani and Tobajishchini. The twins have many adventures in which they helped to rid the world of various monsters. Multiple batches of modern humans were created a number of times in the Fourth World and the Diyin Dine'e gave them.

First/Black World:

The beginning of time. In the First World, there lived various spiritual beings. They were given Navajo names describing certain insects and animals. Altse Hastiin (First Man) and Altse Asdzaa(First Woman) were created. The beings couldn't get alson with one another so they decided to leave through an opening in the east into the Second World.

Second/Blue World:

This world was already occupied by the Blue Birds, animals and other beings who were in disagreement and couldn't get along with one another. There was severe hardship so they decided to leave this world. First Man made a want of white shell, turquoise, abalone, and jet. This wand carried everyone through an opening in the south into the Third World.

Third/Yellow World:

This world was entered first by Bluebird, First Man, First Woman, Coyote, and other beings. This land had great rivers crossing from east to west and north to south. One day, Coyote stole Water Baby from the river, causing a great flood. First Man ordered everyone to climb into the reed to escape the rising waters. As the beings climbed out of the reed into the Fourth World, the people discovered Coyote was the one who had stole Water Baby. Coyote took the Water Baby back to its mother and the flooded waters began to recede.

Fourth/White World:

Locust was the first to enter the fourth world. He saw water everywhere and other beings living there. The beings in the Fourth World would not let the beings from the Third World to enter unless the Locust passed certain tests. Locust passed all the tests and the people entered into the Fourth World. Later, First Man and First Woman formed the four sacred mountains. The sacred dirt was brought from the First World to form these mountains.

South: This is our planning direction where we plan what we are going to do. The sun sets in the...

West: This is our life, and is where we do our living. Here is where we act out our plan and our thoughts of the east and south directions of our lives. The sun sets in the west.

North: This is the evaluation portion of our lives. This is where we get our satisfaction and we evaluate the outcome of what we first started in the east. Here is where we determine to change things to make it better, or to see we are on the right path and should continue the cycle.

Every day the cycle is repeated. In each cycle there is a lesson to be learned. During the day when we fall, we stand back up and see what we can do differently the next day. Each dawn is a new start. If you are an alcoholic, if you are a drug abuser, if you did something in the past, early dawn is when you can start a new life again. There is a new renewal. This is how much Mother Earth and Father Sky love us. They give us the chance every morning to start our life new. The Creator answers our prayers in the early morning. We ask for their guidance and assistance to help us with whatever we do.

Turquoise Navajo Sacred Stone

Turquoise is considered one of the four sacred stones of the Navajo. For centuries they have regarded it as a valuable talisman and take pride in its possession. Sheepherders have carried a turquoise fetish to insure fertility of the sheep, hunters to insure success in the hunt, and warriors to insure victory and a safe return.

Traditionally a bead of turquoise was fastened to a lock of hair to protect the Navajo from being struck by lightning and believed to be a safeguard against snake bite. Every household would have a buckskin pouch of herbs, turquoise and shell to add protection against any unexpected event or catastrophe.

As with all cultures around the world, the Navajo have an End Time Prophecy. When we invite total truth into our Sacred Space, we shatter the bonds of separation and illusion. The Whirling Rainbow of Peace destroys the lies that made the Children of the Earth mistrust one another and replaces the illusion of separation with the truth of unity.

When the Whirling Rainbow Woman of the Navaho and Hopi brings the cleansing regenerative rains to the Earth Mother, her children are also cleansed and healed. When the Rainbow of Peace of the Seneca encircles each person's sacred space, all will walk in truth respecting the Sacred Space of others and harmony of living on Earth will be restored. These Knowing Systems are the teachings of the Warriors of the Rainbow who are Sisters and Brothers uniting the Fifth World and working for Peace.

The Navajo need no separate word for religion; all life is lived in sacred relationship to the land. With healing ceremonies to bring them back to harmony with each other, they sing of a beauty and harmony which is apparent to all visitors to Navajo Country.

Navajo legend says that the Dine had to pass through three different worlds before emerging into the present world - the Fourth World or Glittering World. So, the Holy People put four sacred mountains in four different directions. Mt. Blanca in the east. Mt. Taylor in the south, San Francisco Peaks in the west, and Mt. Hesperus in the north, thus creating the boundaries of Navajo land.

Centuries ago, the Navajo people were taught by the Holy People to live in harmony with Mother Earth and how to conduct their many activities of everyday life. The Dineh believe there are two classes of beings: the Earth People and the Holy People. The earth People are ordinary mortals, while the Holy People are spiritual beings that cannot be seen. Holy People are believed to aid or harm Earth People.

When disorder happens in a Navajo's life, such as illness, herbs, medicinemen (diagnosticians), prayers, songs and ceremonies are used to help cure the ailment. Some tribal members prefer modern day hospitals on the Navajo Reservation; some seek the assistance of a traditional Navajo medicineman, some combine both methods.

Navajos believe that a medicineman is a uniquely qualified individual bestowed with supernatural powers to diagnose a person's problem and to heal or cure illnesses. The Dineh believe they are sustained as a nation because of their enduring faith in the Great Spirit. And because of their strong spirituality, the Navajo people believe they will continue to survive as an Indian nation forever.

For a Navajo, to be a well balanced person, he/she must have equal development in the four values of life. When a Navajo has been well taught in all areas of life, that person is a harmonious person and well educated. Just as corn needs four things: sunlight, water, air, and soil to grow; so a Navajo needs the four values: values of Life, values of Work, values of Social/Human Relations, and values of Respect/Reverence to grow.

Navajo spiritual practice is about restoring balance and harmony to a person's life to produce health. One exception to the concept of healing is the Beauty Way ceremony: the Kinaalda, or a female puberty ceremony. Others include the Hooghan Blessing Ceremony and the "Baby's First Laugh Ceremony." Otherwise, ceremonies are used to heal illnesses, strengthen weakness, and give vitality to the patient. Ceremonies restore Hozhq, or beauty, harmony, balance, and health.

When suffering from illness or injury, Navajos traditionally seek a certified, credible Hatalii (medicine man) for healing, before turning to Western medicine (e.g., hospitals). The medicine man will use several methods to diagnose the patient's ailments. This may include using special tools such as crystal rocks, and abilities such as hand-trembling and Hatal (chanting prayer). The medicine man chooses a specific healing chant for that type of ailment. Short prayers for protection may take only a few hours, and in some cases, the patient is expected to do a follow-up afterward. The medicine man may give advice, such as avoiding sexual relations, personal contact, animals, certain foods, and certain activities for a period of time; it is not unlike a doctor's advice.

The Navajo believe that certain ailments can be caused by violating taboos. Contact with lightning-struck objects, exposure to taboo animals such as snakes, and contact with the dead create the need for healing afterward. Protection ceremonies, especially the Blessing Way Ceremony, are used for Navajo who leave the boundaries of the four sacred mountains. It is used extensively for Navajo warriors or soldiers going to war.

Upon return, the person receives an Enemy Way Ceremony, or Nidaa, to get rid of the evil elements in the body, and to restore balance in his or her life. This is important for Navajo warriors or soldiers returning from battle. Warriors or soldiers often suffer spiritual or psychological damage from participating in warfare, and the Enemy Way Ceremony helps restore harmony to the person, mentally and emotionally.

Some ceremonies cure people from curses. People may complain of witches and skin-walkers that do harm to their minds, bodies, and families. The ailments are not necessarily physical and may take other forms. The medicine man is often able to break the curses that witches and skin-walkers put on families. Mild cases do not take very long, but for extreme cases, special ceremonies are needed to drive away the evil spirits.

The medicine man may find curse objects implanted inside the victim's body. These objects are used to cause the person pain and illness. Examples of such objects include bone fragments, rocks and pebbles, bits of string, snake teeth, owl feathers, and turquoise jewelry.

The medicine men learn fifty-eight to sixty sacred ceremonies. Most of them last four days or more; to be most effective, they require that relatives and friends attend and help out. Outsiders are discouraged from participating, as they may become a burden to others or violate a taboo. This could affect the turnout of the ceremony. The ceremony must be done in precisely the correct manner to heal the patient. This includes everyone who is involved.

The medicine man must be able to correctly perform a ceremony from beginning to end. If he does not, the ceremony will not work. A Hatalii learns as an apprentice to a master, and the study is extensive, arduous, and takes many years. The apprentice learns everything by watching his teacher, and memorizes the words to all the chants. If a medicine man cannot learn all sixty of the ceremonies, he may choose to specialize in a select few.

The origin of spiritual healing ceremonies is part of Navajo mythology. It is said the first Enemy Way ceremony was performed for Changing Woman's twin sons (Monster Slayer and Born-For-the-Water) after slaying the Giants and restoring Hozhq to the world and people. The patient identifies with Monster Slayer through the chants, prayers, sandpaintings, herbal medicine and dance.

Another Navajo healing, the Night Chant ceremony, is administered as a cure for most types of head ailments, including mental disturbances. The ceremony, conducted over several days, involves purification, evocation of the gods, identification between the patient and the gods, and the transformation of the patient. Each day entails the performance of certain rites and the creation of detailed sand paintings.

On the ninth evening a final all-night ceremony occurs, in which the dark male thunderbird god is evoked in a song that starts by describing his home:

The essence of the Navajo religion is the relationship between the navajo people and their land, which is the basis of life itself. Rituals and ceremonies are a vital part of the Navajo's everyday routine. To the navajo people "the earth and all that exists in the natural world are manifestations of the natural order of things". They are taught to live in harmony with Mother Earth, to maintain a balance between individual and universe, live in harmony with nature and the creator, observing the natural order of life and live in accordance with it.

The majority of Navajo ceremonies are for curing mental and physical problems and for restoring universal harmony, once disturbed. In these ceremonies, many dry paintings or sand altars are made, depicting the characters and incidents of myths.

Most Navaho ceremonies are conducted, at least primarily, for the purpose of healing disease; and while designated medicine ceremonies, they are, in fact, ritualistic prayers.There are so many ceremonies that no student has yet determined their number, which reaches into scores, while the component ritual prayers of some number hundreds. The principal ceremonies are those that require nine days and nine nights in their performance. Each is based on a mythic story, and each has four dry-paintings, or so-called altars. besides these nine days' ceremonies there are others whose performance requires four days, and many simpler ones requiring only a single day, each with its own dry-painting.

The Navajo culture is kept alive through ceremony. There are many ceremonies for different things. The ceremonies were given by the Holy ones. Through these ceremonies, the important lessons are taught to help preserve us as a people, The ceremony teaches about history and responsibilities as a human being inside the universe and the Navajo's place in it. They teach about this world, and how one can also help with this world. It also teaches patience.

Through ceremony the language is kept alive. The ceremony is also the place to talk with the Holy Ones and the Creator. They help to bless the sick in body and mind. Ceremonies are also used to celebrate joyous occasions and they are also used to help solve problems within Navajo society and within the family. During these counsels everyone must agree on what is best, or they will come together again until they can. Navajo music is a very important part of the ceremony and also has great power.

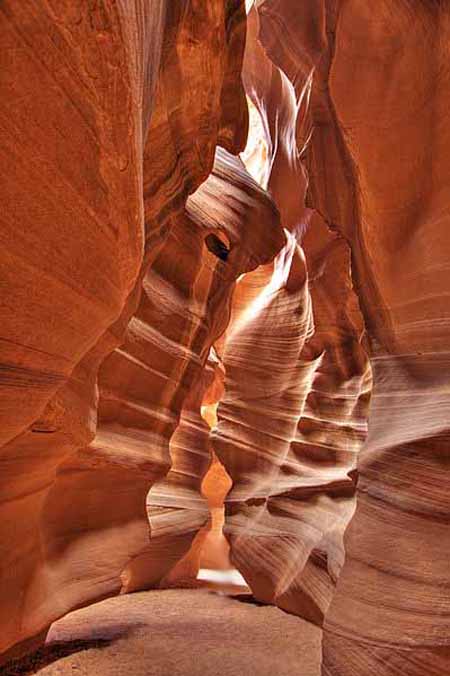

Antelope Canyon is the most-visited and most-photographed slot canyon in the American Southwest. It is located on Navajo land near Page, Arizona. Antelope Canyon includes two separate, photogenic slot canyon sections, referred to individually as Upper Antelope Canyon or The Crack; and Lower Antelope Canyon or The Corkscrew.

Lower Antelope Canyon is Hazdistazi ("Hasdestwazi", or "spiral rock arches."

Both are located within the LeChee Chapter of the Navajo Nation.

The lower canyon is in the shape of a "V" and shallower than the Upper Antelope.

Canyon De Chelly lies in the heart of the land of the Navajo between the Four Sacred Mountains. This is a very sacred and beautiful place. It is a place where all the life giving sources are abundant. It is a place of great peace where important lessons can be learned. There are ancient ruins in the canyon.

The people who lived in them form a basis of who and what we are today. This is one of the most important places for a Navajo to visit today. For millennia our people have been coming to this canyon to receive of the great strength and power that is found here. The Navajo past and present is hidden within the walls of this hallowed place.

Rather than reaching skyward from the plains as most mountains do, the canyon is hidden from the world until one happens upon it. Some of the most important things that have happened for our people has happened within this canyon. On the top of Canyon De Chelly is one of the places the Holy Ones first set their foot. This is a very holy place. It is here within the canyon that the Holy Ones taught us how to live.

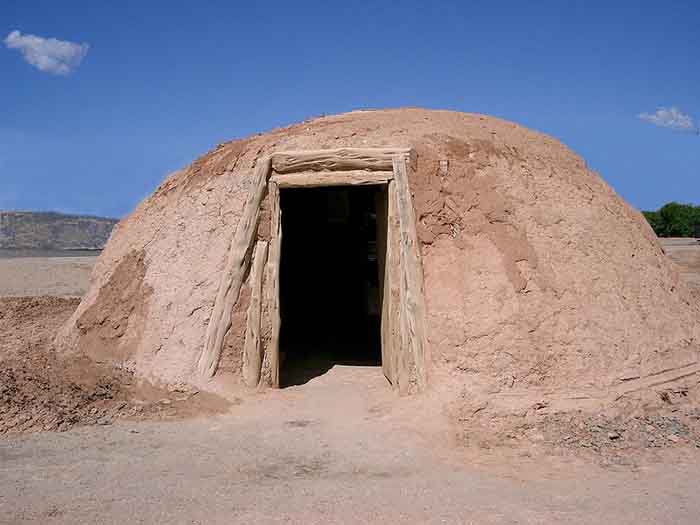

A hogan is the traditional Navajo home. These eight-sided houses are made of wood and covered in mud, with the door always facing east to welcome the sun each morning. Hogans are houses made of poles and brush covered with earth. Navajos have several types of hogans for lodging and ceremonial use. Ceremonies, such as healing ceremonies will take place inside a hogan. According to Kehoe, this style of housing is distinctive to the Navajo, and he writes, "even today, a solidly constructed, log walled Hogan is preferred by many Navajo families." Most Navajo members today live in apartments and houses in urban areas.

For those who practice the Navajo religion, the hogan is considered sacred. The religious song "The Blessingway" describes the first hogan as being built by Coyote with help from beavers to be a house for First Man, First Woman, and Talking God. The Beaver People gave Coyote logs and instructions on how to build the first hogan. Navajos made their hogans in the traditional fashion until the 1900s, when they started to make them in hexagonal and octagonal shapes. Today they are rarely used as dwellings, but are maintained primarily for ceremonial purposes.

The Navajo people traditionally hold the four sacred mountains as the boundaries of the homeland they should never leave: Blanca Peak (Sisnaajini - Dawn or White Shell Mountain) in Colorado; Mount Taylor (Tsoodzi - Blue Bead or Turquoise Mountain) in New Mexico; the San Francisco Peaks (Dook'o'oosid - Abalone Shell Mountain) in Arizona; and Hesperus Mountain (Dibe Nitsaa - Big Mountain Sheep) in Colorado.

Betatakin Ruin, one of three spectacular cliff dwelings in Navajo National Monument, is located in the Navajo Nation in Northern Arizona. The monument contains some of the best ruins on the Colorado Plateau. Betatakin and Keet Seel are seasonally open to the public.

Spider Rock stands with awesome dignity and beauty over 800 feet high in Arizona's colorful Canyon de Chelly National Park (pronounced da Shay). Geologists of the National Park Service say that "the formation began 230 million years ago. Windblown sand swirled and compressed with time created the spectacular red sandstone monolith. Long ago, the Dine (Navajo) Indian tribe named it Spider Rock.

Stratified, multicolored cliff walls surround the canyon. For many, many centuries the Dine (Navajo) built caves and lived in these cliffs. Most of the caves were located high above the canyon floor, protecting them from enemies and flash floods.

Spider Woman possessed supernatural power at the time of creation, when Dine (Navajo) emerged from the third world into this fourth world - the world of Time and Physicality.

At that time, monsters roamed the land and killed many people. Since Spider Woman loved the people, she gave power for Monster-Slayer and Child-Born-of-Water to search for the Sun-God who was their father. When they found him, Sun-God showed them how to destroy all the monsters on land and in the water.

Because she preserved their people, Dine (Navajo) established Spider Woman among their most important and honored Deities. She chose the top of Spider Rock for her home. It was Spider Woman who taught Navajo ancestors of long ago the art of weaving upon a loom.

She told them, "My husband, Spider Man, constructed the weaving loom making the cross poles of sky and earth cords to support the structure; the warp sticks of sun rays, lengthwise to cross the woof; the healds of rock crystal and sheet lightning, to maintain original condition of fibers. For the batten, he chose a sun halo to seal joints, and for the comb he chose a white shell to clean strands in a combing manner." Through many generations, the Dine (Navajo) have always been accomplished weavers.

From their elders, Dine (Navajo) children heard warnings that if they did not behave themselves, Spider Woman would let down her web- ladder and carry them up to her home and devour them. The children also heard that the top of Spider Rock was white from the sun-bleached bones of Dine (Navajo) children who did not behave themselves.

One day, a peaceful cave-dwelling Dine (Navajo) youth was hunting in Dead Man's Canyon, a branch of Canyon de Chelly. Suddenly, he saw an enemy tribesman who chased him deeper into the canyon. As the peaceful Dine (Navajo) ran, he looked quickly from side to side, searching for a place to hide or to escape.

Directly in front of him stood the giant obelisk-like Spider Rock. What could he do? He knew it was too difficult for him to climb. He was near exhaustion. Suddenly, before his eyes he saw a silken cord hanging down from the top of the rock tower.

The Dine (Navajo) youth grasped the magic cord. which seemed strong enough, and quickly tied it around his waist. With its help he climbed the tall tower, escaping from his enemy who then gave up the chase. When the peaceful Dine (Navajo) reached the top, he stretched out to rest. There he discovered a most pleasant place with eagle's eggs to eat and the night's dew to drink.

Imagine his surprise when he learned that his rescuer was Spider Woman. She told him how she had seen him and his predicament. She showed him how she made her strong web-cord and anchored one end of it to a point of rock. She showed him how she let down the rest of her web-cord to help him to climb the rugged Spider Rock.

Later, when the peaceful Dine (Navajo) youth felt assured his enemy was gone, he thanked Spider Woman warmly and he safely descended to the canyon floor by using her magic cord. He ran home as fast as he could run, reporting to his tribe how his life was saved by Spider Woman.

Family is very important to the Navajos. There is the immediate family, and the extended family. The extended family is broken up into clans, which were created by the Holy Ones. The four original clans were 'Towering House', 'Bitterwater', 'Big Water' and 'One-who-walks-around'.

Today there are about 130 clans. When we meet another Navajo for the first time we tell each other from what clan they are from. Navahos identify how we are human by the clans of our mother, father, and ancestors. This is who we are. We also have our immediate family. We have a great responsibility to our family, for without the family we as a people would have an end.

The Navajo (Diné) and Apache tribal groups of the American Southwest speak dialects of the language family referred to as Athapaskan. Linguistic similarities indicate the Navajo and Apache were once a single ethnic group, with substantial numbers not present in the American Southwest until the early 1500s.

The Navajo people are very dynamic and creative people who strongly believe in the power of the mind to think and create; finding expression in the myriad symbolic creations of the Navajo language, art and ritual ceremonies.

The Navajo language has a great sense humor in day to day conversation. Humor transforms difficult and frustrating circumstances into bearable and even pleasant situations. The strong emphasis and value Navajos place on humor is evidenced in the First Laugh rite. The first time a Navajo child laughs out loud is a time for honor and celebration.

Aside from being the mother tongue of the Navajo Nation, the Navajo language also has played a highly significant role in helping the entire nation. During World War II, the Navajo language was used as a code to confuse the enemy. Navajo bravery and patriotism is unequaled. Navajos were inducted and trained in the U.S. Marine Corps to become "code talkers" on the front-line. Shrouded in secrecy at the time, these men are known today as the famed Navajo Code Talkers, proved to be the only code that could not be broken during World War II.

Nothing depicts the American Indian better than his love for dancing. The traditional song and dance and inter-tribal pow wows are only some of the many aspects in which the Navajo Nation continues its cultural tradition. Most social events held in Navajoland are held mainly for pleasure and outsiders are welcome to attend.

The traditional song and dance (a ceremony called the Enemyway Ceremony) is an increasingly popular event. One of the reasons an Enemyway Ceremony is conducted is to help cure an individual who has become ill after going to war. The ceremonial dancing is to relieve tension in the patient.

Today, the cultural aspects of the ceremony live on through song and dance contests or festivals. Participants dress in their finest traditional Navajo attire and recreate the traditional dances of their forefathers.

Traditional Navajo music is always vocal, with most instruments, which include drums, drumsticks, rattles, rasp, flute, whistle, and bullroarer, being used to accompany singing of specific types of song (Frisbie and McAllester 1992). As of 1982, there were over 1,000 Hataalii or Singers otherwise known as 'Medicine People', qualified to perform one or more of thirty ceremonials and countless prayer rituals (which restore hozho which holds the semantic field of 'harmonious condition' and 'beauty', good health, serenity, and balance.

These songs are the most sacred holy songs, the "complex and comprehensive" spiritual literature of the Navajo, may be considered classical music (McAllester and Mitchell 1983), while all other songs, including personal, patriotic, daily work, recreation, jokes, and less sacred ceremonial songs, may be considered popular music. The "popular" side is characterized by public performance while the holy songs are preserved of their sacredness by reserving it only for ceremonies (and thus not featured on the recording listed at bottom).

The longest ceremonies may last up to ten days and nights while performing rituals that restore the balance between good and evil, or positive and negative forces. The hataalii aided by sandpaintings or masked yeti bicheii, as well as numerous other sacred tools used for healing, chant the sacred songs to call upon the Navajo gods and natural forces to restore the person to harmony and balance within the context of the world forces. In ceremonies involving sandpaintings, the person to be supernaturally assisted, the patient, becomes the protagonist, identifying with the gods of the Diné Creation Stories, and at one point becomes part of the Story Cycle by sitting on a sandpainting with iconography pertaining to the specific story and deities.

The lyrics, which may last over an hour and are usually sung in groups, contain narrative epics including the beginning of the world, phenomenology, morality, and other lessons. Longer songs are divided into two or four balanced parts and feature an alternation of chant-like verses and buoyant melodically active choruses concluded by a refrain in the style and including lyrics of the chorus. Lyrics, songs, groups, and topics include cyclic: Changing Woman, an immortal figure in the Navajo traditions, is born in the spring, grows to adolescence in the summer, becomes an adult in the autumn, and then an old lady in the winter, repeating the life cycles over and over. Her sons, the Hero Twins, Monster Slayer and Born-for-the-Water, are also sung about, for they rid the world of giants and evil monsters. Stories such as these are spoken of during these sacred ceremonies.

The "popular" music resembles the highly active melodic motion of the choruses, featuring wide intervallic leaps and melodic range usually an octave to octave and a half. Structurally, the songs are created from the complex repetition, division, and combinations of most often no more than four or five phrases, with short songs often immediately following each other for continuity as needed in work songs. Their lyrics are mostly vocables, with certain vocables specific to genres, but may contain short humorous or satirical texts.

Long ago when the animals roamed the earth they came together to play Keshjee', or the Navajo moccasin game. Ye'iitsoh (Giant) and Owl discussed putting a game together and they came up with the Navajo Shoegame. There is a story that goes with this, however it remains only to be heard orally by a Diné. Today throughout the Navajo Nation, many families play the Navajo Shoegame.

At times, local communities play against each other during the winter season. There are also many prominent Navajo Shoegame singers throughout the Navajo Nation. Notably the Nez Family of Hunter's Point, Arizona and Pinedale, New Mexico, who are very well known for their singing and playing of the game. Leo Nez Sr. and his son Titus Jay Nez who come from the Nez family are very well known for their singing of Shoegame songs and attendance of Shoegames throughout the Navajo Nation. Other notable members include Jimmy Cody, and Sammie Largo.

Navajo children's songs are usually about animals, such as pets and livestock. Some songs are about family members, and about chores, games, and other activities as well. It usually includes anything in a child's daily life. A child may learn songs from an early age from the mother. As a baby, if the child cries, the mother will sing to it while it's tied in the cradleboard. Navajo songs are rhythmic, and therefore soothing to a baby. Thus, songs are a major part of Navajo culture.

It may have been a kind of beginner's course in learning the songs and prayers for self-protection from bad things, skinwalkers, and other evil figures in Navajo traditions. Blessings, such as when one does with corn pollen in the early morning, may be learned as well.

In children's songs, a short chant usually starts off the song, followed by at least one stanza of lyrics, and finishing up with the same chant. All traditional songs include chants, and are not made up solely of lyrics. There are specific chants for some types of songs as well. Contemporary children's songs, however, such as Christmas songs and Navajo versions of nursery rhymes, may have lyrics only. Today, both types of songs may be taught in elementary schools on the reservation, depending on the knowledge and ability of the particular teacher.

In earlier times, Navajo children may have sung songs like these to themselves while sheepherding, to pass the time. Sheep were, and still are, a part of Navajo life. Back then, giving a child custody of the entire herd was a way to teach them leadership and responsibility, for one day they would probably own a herd of their own. A child, idle while the sheep grazed, may sing to pass the time.

Peyote songs are a form of Native American music, now most often performed as part of the Native American Church, which came to the northern part of the Navajo Nation around 1936. They are typically accompanied by a rattle and water drum, and are used in a ceremonial aspect during the sacramental taking of peyote. Peyote songs share characteristics of Apache music and Plains-Pueblo music. In recent years, a modernized version of peyote songs have been popularized by Verdell Primeaux, a Sioux, and

The Navajo music scene is perhaps one of the strongest in native music today. In the past, Navajo musicians were tallied into maintaining the status quo of traditional music, chants and/or flute compositions. Today, Navajo bands span the genres of punk, metal, hardcore, hip hop, blues, rock, death metal, black metal, stoner rock, country, and even traditional.

Success of bands like Blackfire, Ethnic De Generation, Downplay, Mother Earth Blues Band, Aces Wild, Tribal Live, The Plateros and other musicians have reignited an interest in music with the younger Navajo generations. Perhaps the best synthesis of tradition and contemporary is found in the musical marriage of Tribe II Entertainment, a rap duo from Arizona, Mistic, Rollin, Lil' Spade and Shade are truly right now, the only Native American rappers who can rap entirely in their native tongue. Their popularity and bilingual ability is yet another look at the prolific nature of the Navajo music scene.

Silversmithing is an important art form among Navajo. Atsidi Sani (ca. 1830-ca. 1918) is considered to be the first Navajo silversmith. He learned silversmithing from a Mexican man called Nakai Tsosi ("Thin Mexican") around 1878 and began teaching other Navajos how to work with silver.

By 1880, Navajo silversmiths were creating handmade including bracelets, tobacco flasks, necklaces and bracers. Later, they added beautiful silver earrings, buckles, bolos, hair ornaments, pins and squash blossom necklaces for tribal use, and to sell to tourists as a way to supplement their income.

The Navajo's hallmark jewelry piece called the "squash blossom" necklace first appeared in the 1880s. The term "squash blossom" was apparently attached to the name of the Navajo necklace at an early date, although its bud-shaped beads are thought to derive from Spanish-Mexican pomegranate designs.

The Navajo silversmiths also borrowed the "naja" (najahe in Navajo symbol to shape the silver pendant that hangs from the "squash blossom" necklace.

Turquoise has been part of jewelry for centuries, but Navajo artists did not use inlay techniques to insert turquoise into silver designs until the late 19th century.

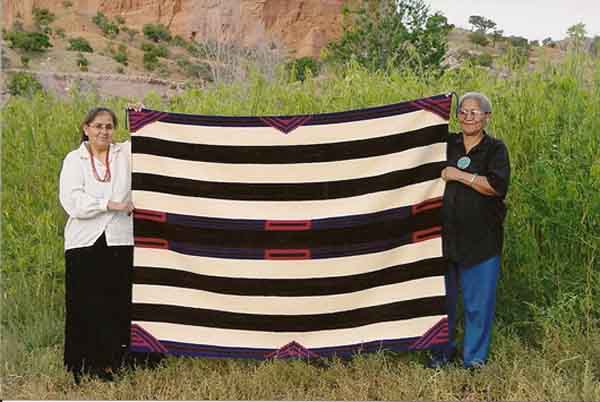

Navajo came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; however, they learned to weave cotton on upright looms from Pueblo peoples. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. By the 18th century the Navajo had begun to import Bayeta red yarn to supplement local black, grey, and white wool, as well as wool dyed with indigo.

Using an upright loom, the Navajo made extremely fine utilitarian blankets that were collected by Ute and Plains Indians. These Chief's Blankets, so called because only chiefs or very wealthy individuals could afford them, were characterized by horizontal stripes and minimal patterning in red. First Phase Chief's Blankets have only horizontal stripes, Second Phase feature red rectangular designs, and Third Phase feature red diamonds and partial diamond patterns.

The completion of the railroads dramatically changed Navajo weaving. Cheap blankets were imported, so Navajo weavers shifted their focus to weaving rugs for an increasingly non-Native audience. Rail service also brought in Germantown wool from Philadelphia, commercially dyed wool which greatly expanded the weavers' color palettes.

Some early European-American settlers moved in and set up trading posts, often buying Navajo rugs by the pound and selling them back east by the bale. The traders encouraged the locals to weave blankets and rugs into distinct styles.

These included "Two Gray Hills" (predominantly black and white, with traditional patterns); Teec Nos Pos (colorful, with very extensive patterns); "Ganado" (founded by Don Lorenzo Hubbell), red-dominated patterns with black and white; "Crystal" (founded by J. B. Moore); oriental and Persian styles (almost always with natural dyes); "Wide Ruins", "Chinlee", banded geometric patterns; "Klagetoh", diamond-type patterns; "Red Mesa" and bold diamond patterns. Many of these patterns exhibit a fourfold symmetry, which is thought to embody traditional ideas about harmony or hozhq.

Today Navajo weaving is a fine art, and weavers opt to work with natural or commercial dyes and traditional, pictorial, or a wide range of geometric designs.

The art of Navajo weaving reflects a wondrous spiritual quality that transcends all time. Weaving a rug is a slow, painstaking process that begins with shearing the wool. The wool is then spun by hand, often as many as 16 to 20 times. In some cases, the wool threads are left in their natural state. In others, the yarn is dyed with natural vegetal dyes such as those from grapes, oak, juniper, choke cherry, prickly pear cactus, larkspur, Navajo tea, and wild plum roots.

The colors are both rich and subtle at the same time. Shadings of peach, orange, coral, green, tan, purple, and other natural hues create a breathtaking display of color.

The patterns of the rugs are learned in childhood, and passed on from generation to generation. There are no written directions. Designs are memorized by the artists. That's why certain artists specialize in certain designs. These are the patterns that their mothers or grandmothers taught them long ago.

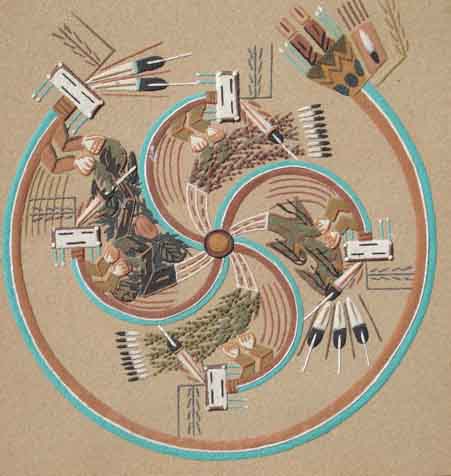

Sandpaintings are another unique and symbolic art form originating with the Holy People who lived in the underworld. Sandpaintings were, and still are, primarily ceremonial.

Depicting the tools used by the Holy People, which were strictly intended for ceremonial purposes, sand paintings represent an array of ceremonies and sacred songs. However, today many artists create pictures of ceremonial figures for commercial purposes. Sand painting in itself is not forbidden as long as Holy people are not depicted.

Tribal legend indicates that most Navajo arts and crafts sprang from roots that began with the Holy People. Virtually everything a Navajo says or does is somehow linked with his cultural past, consequently they help him set the course for the future. Navajo land is, as it has always been, a land in transition, a blending of the past and the present, reaching out confidently to embrace the future.

This sandpainting is similar to one that is done during a Blessing Way ceremony. The representation of Sun Father is in the center, the four sacred plants like spokes from the center, and four deities. As with all ceremonial paintings, each symbol has specific meaning with its own story and chants.

Navajo people believe the universe to be delicately balanced. Only man can upset it, causing disaster and/or illness. Each illness or disaster has a particular part that is related to a portion of Navajo history. Balance is restored in the universe by healing the offender with chants, herbs, prayers, songs, and sandpaintings.

The Healer (Medicine Man) or Singer goes to the offenders hogan. Restoration begins with chanting accompanied by rattles and recounting adventures of Navajo heroes.

The sand painting is begun on a bed of clean white sand on the dirt floor, Mother Earth.

Sand paintings are created with an opening facing east - the same direction as the door to the hogan, to make it difficult for evil to enter. In the sandpainting design itself, the rainbow yei is used to provide protection for the design.

Each design and figure must be produced carefully and in a knowledgeable way, using only the five sacred colors of sands. Every detail must be completed with exactness, or the harmony of the universe will not be restored, but worsened.

Decorative variations can be left out, but never introduced to a ceremonial sandpainting.

Some symbolic designs provide additional power or strength; i.e., buffalo horns added to increase the dosage. When the sandpainting is completed, the patient is seated in its center.

The Medicine Man then touches a particular place on the painting and relays the medicine by touching the patient, restoring harmony and health.

The sand painting is then erased and swept into a blanket. Before sunset, it is carried outside and blown into the wind, returning it to Mother Earth so that trapped evil forces will not escape. sandpaintings which are done at night ceremonies are similarly destroyed before sunrise.

There are more than a thousand ceremonial sandpaintings; less than half are produced today. Many are only in the memories of Medicine Men and unless they are recorded in some way, will be lost as these old men die off.

In addition to healing, sandpaintings have been used to relate folklore stories. One of the most common is The Coyote Stealing Fire part of the Navajo creation story myth.

In 2000 the documentary The Return of Navajo Boy was shown at the Sundance Film Festival. It was written in response to an earlier film, The Navajo Boy which was somewhat exploitative of the Navajo People involved. The Return of Navajo Boy allowed the Navajo People to be more involved in the depicting of their own people.

In the final episode of the third season of the FX reality TV show 30 Days, the shows producer Morgan Spurlock spends thirty days living with a Navajo family on their reservation in New Mexico. The July 2008 show called Life on an Indian Reservation, depicts the dire conditions that many Native Americans experience living on reservations in the United States.

Navajo Wikipedia

Tribal Fates: Why the Navajo Have Succeeded Live Science - November 18, 2011

While other tribes have disappeared from North America over the centuries, the Navajo Nation has done the opposite. Two geographers from the University of California, Los Angeles, offer an explanation for why the Navajos have been able to grow to more than 300,000 members today: a combination of geography and culture. Jared Diamond and Ronan Arthur propose that the geographical isolation and cultural flexibility of the Navajos, who call themselves the Dine, allowed them to expand, even after the arrival of Europeans in North America in 1492 and efforts four centuries later to assimilate them into white U.S. culture.