Ramesses II (c. 1303 BC - July or August 1213 BC), referred to as Ramesses the Great, was the third Egyptian pharaoh (reigned 1279 BC - 1213 BC) of the Nineteenth Dynasty. He is often regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the Egyptian Empire. His successors and later Egyptians called him the "Great Ancestor".

Ramesses II led several military expeditions into the Levant, re-asserting Egyptian control over Canaan. He also led expeditions to the south, into Nubia, commemorated in inscriptions at Beit el-Wali and Gerf Hussein.

At age fourteen, Ramesses was appointed Prince Regent by his father Seti I. He is believed to have taken the throne in his late teens and is known to have ruled Egypt from 1279 BC to 1213 BC for 66 years and 2 months, according to both Manetho and Egypt's contemporary historical records.

He was once said to have lived to age 99, but it is more likely that he died in his 90th or 91st year. If he became Pharaoh in 1279 BC, as most Egyptologists today believe, he would have assumed the throne on May 31, 1279 BC, based on his known accession date of III Shemu day 27.

Ramesses II celebrated an unprecedented 14 sed festivals (the first held after thirty years of a pharaoh's reign, and then every three years) during his reign - more than any other pharaoh. On his death, he was buried in a tomb in the Valley of the Kings - his body was later moved to a royal cache where it was discovered in 1881, and is now on display in the Cairo Museum.

The early part of his reign was focused on building cities, temples and monuments. He established the city of Pi-Ramesses in the Nile Delta as his new capital and main base for his campaigns in Syria. This city was built on the remains of the city of Avaris, the capital of the Hyksos when they took over, and was the location of the main Temple of Set. He is also known as Ozymandias in the Greek sources, from a transliteration into Greek of a part of Ramesses's throne name, Usermaatre Setepenre, "Ra's mighty truth, chosen of Ra".

Ramesses II had 200 wives and concubines, 96 sons and 60 daughters.

Ramesses built extensively throughout Egypt and Nubia, and his cartouches are prominently displayed even in buildings that he did not actually construct. There are accounts of his honor hewn on stone, statues, remains of palaces and temples, most notably the Ramesseum in the western Thebes and the rock temples of Abu Simbel. He covered the land from the Delta to Nubia with buildings in a way no king before him had done. He also founded a new capital city in the Delta during his reign called Pi-Ramesses; it had previously served as a summer palace during Seti I's reign.

His memorial temple Ramesseum, was just the beginning of the pharaoh's obsession with building. When he built, he built on a scale unlike almost anything before. In the third year of his reign Ramesses started the most ambitious building project after the pyramids, that were built 1,500 years earlier. The population was put to work on changing the face of Egypt.

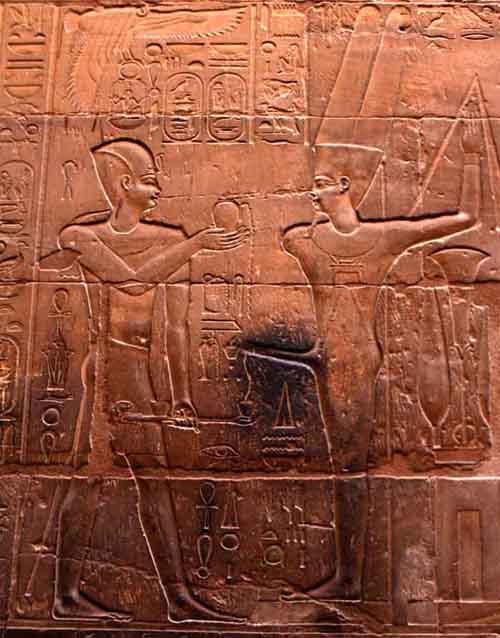

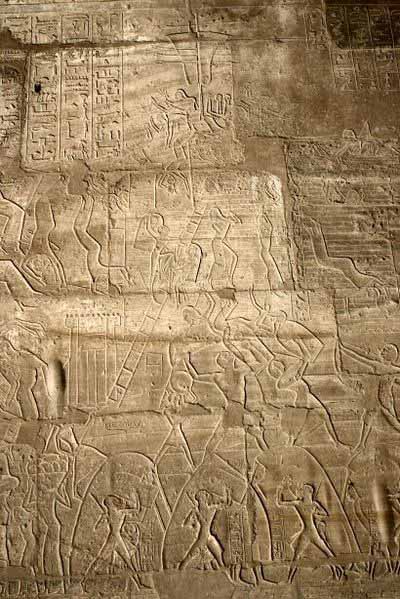

In Thebes, the ancient temples were transformed, so that each one of them reflected honor to Ramesses as a symbol of this divine nature and power. Ramesses decided to eternalize himself in stone, and so he ordered changes to the methods used by his masons. The elegant but shallow reliefs of previous pharaohs were easily transformed, and so their images and words could easily be obliterated by their successors. Ramesses insisted that his carvings be deeply engraved in the stone, which made them not only less susceptible to later alteration, but also made them more prominent in the Egyptian sun, reflecting his relationship with the sun god, Ra.

Ramesses constructed many large monuments, including the archeological complex of Abu Simbel, and the Mortuary temple known as the Ramesseum. He built on a monumental scale to ensure that his legacy would survive the ravages of time. Ramesses used art as a means of propaganda for his victories over foreigners and are depicted on numerous temple reliefs. Ramesses II also erected more colossal statues of himself than any other pharaoh. He also usurped many existing statues by inscribing his own cartouche on them.

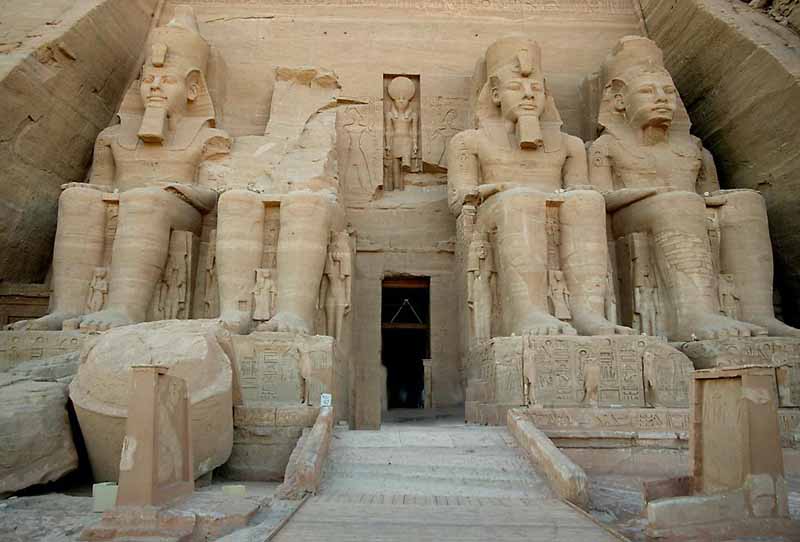

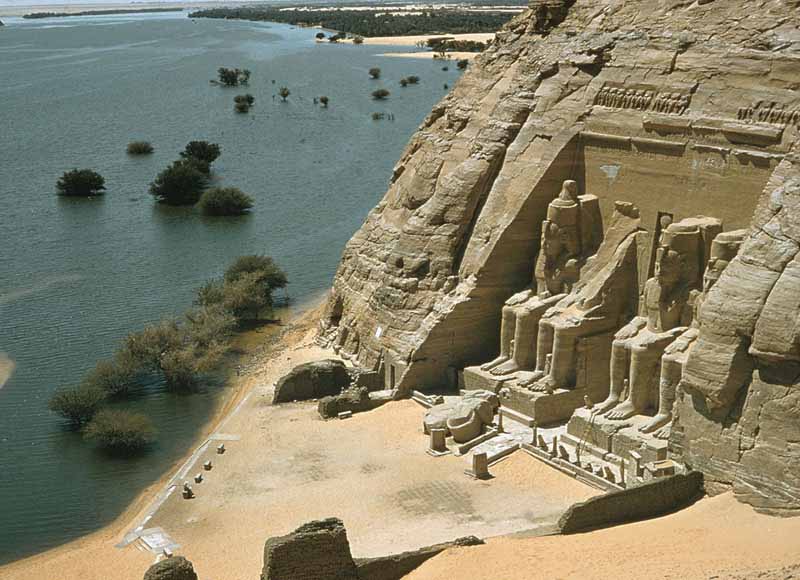

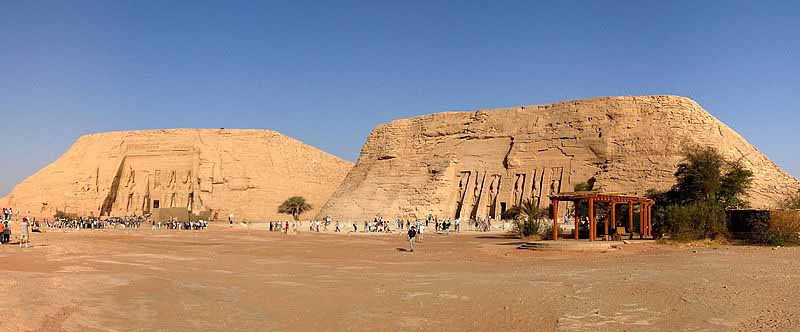

The Abu Simbel temples are two massive rock temples in Abu Simbel in Nubia, southern Egypt. They are situated on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about 230 km southwest of Aswan (about 300 km by road). The complex is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the "Nubian Monuments," which run from Abu Simbel downriver to Philae (near Aswan).

The complex consists of two temples. The larger one is dedicated to Ra-Harakhty, Ptah and Amun, Egypt's three state deities of the time, and features four large statues of Ramesse II in the facade. The smaller temple is dedicated to the goddess Hathor, personified by Nefertari, Ramesses's most beloved of his many wives.

The twin temples were originally carved out of the mountainside during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II in the 13th century BC, as a lasting monument to himself and his queen Nefertari, to commemorate his alleged victory at the Battle of Kadesh, and to intimidate his Nubian neighbors. However, the complex was relocated in its entirety in 1968, on an artificial hill made from a domed structure, high above the Aswan High Dam reservoir.

The relocation of the temples was necessary to avoid their being submerged during the creation of Lake Nasser, the massive artificial water reservoir formed after the building of the Aswan High Dam on the Nile River. Abu Simbel remains one of Egypt's top tourist attractions.

Construction of the temple complex started in approximately 1264 B.C. and lasted for about 20 years, until 1244 B.C. Known as the "Temple of Ramesses, beloved by Amun," it was one of six rock temples erected in Nubia during the long reign of Ramesses II. Their purpose was to impress Egypt's southern neighbors, and also to reinforce the status of Egyptian religion in the region. Historians say that the design of Abu Simbel expresses a measure of ego and pride in Ramesses II.

In 1959 an international donations campaign to save the monuments of Nubia began: the southernmost relics of this ancient human civilization were under threat from the rising waters of the Nile that were about to result from the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

One scheme to save the temples was based on an idea by William MacQuitty to build a clear fresh water dam around the temples, with the water inside kept at the same height as the Nile. There were to be underwater viewing chambers.

In 1962 the idea was made into a proposal by architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry and civil engineer Ove Arup. They considered that raising the temples ignored the effect of erosion of the sandstone by desert winds. However the proposal, though acknowledged to be extremely elegant, was rejected.

The salvage of the Abu Simbel temples began in 1964 by a multinational team of archeologists, engineers and skilled heavy equipment operators working together under the UNESCO banner; it cost some $40 million at the time. Between 1964 and 1968, the entire site was carefully cut into large blocks (up to 30 tons, averaging 20 tons), dismantled, lifted and reassembled in a new location 65 meters higher and 200 meters back from the river, in one of the greatest challenges of archaeological engineering in history Some structures were even saved from under the waters of Lake Nasser.

Today, thousands of tourists visit the temples daily. Guarded convoys of buses and cars depart twice a day from Aswan, the nearest city. Many visitors also arrive by plane, at an airfield that was specially constructed for the temple complex.

The Great Temple at Abu Simbel, which took about twenty years to build, was completed around year 24 of the reign of Ramesses the Great (which corresponds to 1265 BCE). It was dedicated to the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah, as well as to the deified Rameses himself. It is generally considered the grandest and most beautiful of the temples commissioned during the reign of Rameses II, and one of the most beautiful in Egypt.

Four colossal 20 meter statues of the pharaoh with the double Atef crown of Upper and Lower Egypt decorate the facade of the temple, which is 35 meters wide and is topped by a frieze with 22 baboons, worshippers of the sun and flank the entrance. The colossal statues were sculptured directly from the rock in which the temple was located before it was moved. All statues represent Ramesses II, seated on a throne and wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. The statue to the left of the entrance was damaged in an earthquake, leaving only the lower part of the statue still intact. The head and torso can still be seen at the statue's feet.

Next to the legs of the colossi, there are other statues no higher than the knees of the pharaoh. These depict Nefertari, Ramesses's chief wife, and queen mother Mut-Tuy, his first two sons Amun-her-khepeshef, Ramesses, and his first six daughters Bintanath, Baketmut, Nefertari, Meritamen, Nebettawy and Isetnofret.

The entrance itself is crowned by a bas-relief representing two images of the king worshiping the falcon-headed Ra Harakhti, whose statue stands in a large niche. This god is holding the hieroglyph 'user' and a feather in his right hand, with Ma'at, (the goddess of truth and justice) in his left; this is nothing less than a gigantic cryptogram for Ramesses II's throne name, User-Maat-Re. The facade is topped by a row of 22 baboons, their arms raised in the air, supposedly worshipping the rising sun. Another notable feature of the facade is a stele which records the marriage of Ramesses with a daughter of king Hattusili III, which sealed the peace between Egypt and the Hittites.

The inner part of the temple has the same triangular layout that most ancient Egyptian temples follow, with rooms decreasing in size from the entrance to the sanctuary. The temple is complex in structure and quite unusual because of its many side chambers. The hypostyle hall (sometimes also called a pronaos) is 18 meters long and 16.7 meters wide and is supported by eight huge Osirid pillars depicting the deified Ramses linked to the god Osiris, the god of the Underworld, to indicate the everlasting nature of the pharaoh.

The colossal statues along the left-hand wall bear the white crown of Upper Egypt, while those on the opposite side are wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt (pschent). The bas-reliefs on the walls of the pronaos depict battle scenes in the military campaigns the ruler waged. Much of the sculpture is given to the Battle of Kadesh, on the Orontes river in present-day Syria, in which the Egyptian king fought against the Hittites. The most famous relief shows the king on his chariot shooting arrows against his fleeing enemies, who are being taken prisoner. Other scenes show Egyptian victories in Libya and Nubia.

From the hypostyle hall, one enters the second pillared hall, which has four pillars decorated with beautiful scenes of offerings to the gods. There are depictions of Ramesses and Nefertari with the sacred boats of Amun and Ra-Harakhti. This hall gives access to a transverse vestibule in the middle of which is the entrance to the sanctuary. Here, on a black wall, are rock cut sculptures of four seated figures: Ra-Horakhty, the deified king Ramesses, and the gods Amun Ra and Ptah. Ra-Horakhty, Amun Ra and Ptah were the main divinities in that period and their cult centers were at Heliopolis, Thebes and Memphis respectively.

It is believed that the axis of the temple was positioned by the ancient Egyptian architects in such a way that on October 21 and February 21 (61 days before and 61 days after the Winter Solstice), the rays of the sun would penetrate the sanctuary and illuminate the sculptures on the back wall, except for the statue of Ptah, the god connected with the Underworld, who always remained in the dark.

These dates are allegedly the king's birthday and coronation day respectively, but there is no evidence to support this, though it is quite logical to assume that these dates had some relation to a great event, such as the jubilee celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the pharaoh's rule.

In fact, according to calculations made on the basis of the heliacal rising of the star Sirius (Sothis) and inscriptions found by archaeologists, this date must have been October 22. This image of the king was enhanced and revitalized by the energy of the solar star, and the deified Ramesses the Great could take his place next to Amun Ra and Ra-Horakhty.

Due to the displacement of the temple and/or the accumulated drift of the Tropic of Cancer during the past 3,280 years, it is widely believed that each of these two events has moved one day closer to the Solstice, so they would be occurring on October 22 and February 20 (60 days before and 60 days after the Solstice, respectively).

The NOAA Solar Position Calculator may be used to verify the declination of the Sun for any location on Earth, at any particular date and time.

The temple of Hathor and Nefertari, also known as the Small Temple, was built about one hundred meters northeast of the temple of pharaoh Ramesses II and was dedicated to the goddess Hathor and Ramesses II's chief consort, Nefertari. This was in fact the second time in ancient Egyptian history that a temple was dedicated to a queen.

The first time, Akhenaten dedicated a temple to his great royal wife, Nefertiti. The rock-cut facade is decorated with two groups of colossi that are separated by the large gateway. The statues, slightly more than ten meters high, are of the king and his queen. On either side of the portal are two statues of the king, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt (south colossus) and the double crown (north colossus); these are flanked by statues of the queen and the king. What is truly surprising is that for the only time in Egyptian art, the statues of the king and his consort are equal in size.

Traditionally, the statues of the queens stood next to those of the pharaoh, but were never taller than his knees. This exception to such a long standing rule bears witness to the special importance attached to Nefertari by Ramesses, who went to Abu Simbel with his beloved wife in the 24th year of his reign. As the Great Temple of the king, there are small statues of princes and princesses next to their parents. In this case they are positioned symmetrically: on the south side (at left as you face the gateway) are, from left to right, princes Meryatum and Meryre, princesses Meritamen and Henuttawy, and princes Rahirwenemef and Amun-her-khepeshef, while on the north side the same figures are in reverse order. The plan of the Small Temple is a simplified version of that of the Great Temple.

As the larger temple dedicated to the king, the hypostyle hall or pronaos is supported by six pillars; in this case, however, they are not Osirid pillars depicting the king, but are decorated with scenes with the queen playing the sinistrum (an instrument sacred to the goddess Hathor), together with the gods Horus, Khnum, Khonsu, and Thoth, and the goddesses Hathor, Isis, Maat, Mut of Asher, Satis and Taweret; in one scene Ramesses is presenting flowers or burning incense.

The capitals of the pillars bear the face of the goddess Hathor; this type of column is known as Hathoric. The bas-reliefs in the pillared hall illustrate the deification of the king, the destruction of his enemies in the north and south (in this scenes the king is accompanied by his wife), and the queen making offerings to the goddess Hathor and Mut.

The hypostyle hall is followed by a vestibule, access to which is given by three large doors. On the south and the north walls of this chamber there are two graceful and poetic bas-reliefs of the king and his consort presenting papyrus plants to Hathor, who is depicted as a cow on a boat sailing in a thicket of papyri. On the west wall, Ramesses II and Nefertari are depicted making offerings to god Horus and the divinities of the Cataracts - Satis, Anubis and Khnum.

The rock cut sanctuary and the two side chambers are connected to the transverse vestibule and are aligned with the axis of the temple. The bas-reliefs on the side walls of the small sanctuary represent scenes of offerings to various gods made either by the pharaoh or the queen. On the back wall, which lies to the west along the axis of the temple, there is a niche in which Hathor, as a divine cow, seems to be coming out of the mountain: the goddess is depicted as the Mistress of the temple dedicated to her and to queen Nefertari, who is intimately linked to the goddess.

Each temple has its own priest that represents the king in daily religious ceremonies. In theory, the Pharaoh should be the only celebrant in daily religious ceremonies performed in different temples throughout Egypt. In reality, the high priest also played that role. To reach that position, an extensive education in art and science was necessary, like the one pharaoh had. Reading, writing, engineering, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, space measurement, time calculations, were all part of this learning. The priests of Heliopolis, for example, became guardians of sacred knowledge and earned the reputation of wise men.

The Ramesseum is the memorial temple (or mortuary temple) of Pharaoh Ramesses II ("Ramesses the Great", also spelled "Ramses" and "Rameses"). It is located in the Theban necropolis in Upper Egypt, across the River Nile from the modern city of Luxor. The name was coined by Jean-Francois Champollion, who visited the ruins of the site in 1829 and first identified the hieroglyphs making up Ramesses's names and titles on the walls. It was originally called the House of millions of years of Usermaatra-setepenra that unites with Thebes-the-city in the domain of Amon.

Ramesses II modified, usurped, or constructed many buildings from the ground up, and the most splendid of these, in accordance with New Kingdom Royal burial practices, would have been his memorial temple: a place of worship dedicated to pharaoh, god on earth, where his memory would have been kept alive after his death. Surviving records indicate that work on the project began shortly after the start of his reign and continued for 20 years.

The design of Ramesses's mortuary temple adheres to the standard canons of New Kingdom temple architecture. Oriented northwest and southeast, the temple itself comprised two stone pylons (gateways, some 60 m wide), one after the other, each leading into a courtyard. Beyond the second courtyard, at the centre of the complex, was a covered 48-column hypostyle hall, surrounding the inner sanctuary.

An enormous pylon (gateways, some 60 m wide) stood before the first court, with the royal palace at the left and the gigantic statue of the king looming up at the back.

As was customary, the pylons and outer walls were decorated with scenes commemorating pharaoh's military victories and leaving due record of his dedication to, and kinship with, the gods. In Ramesses's case, much importance is placed on the Battle of Kadesh (ca. 1285 BC); more intriguingly, however, one block atop the first pylon records his pillaging, in the eighth year of his reign, a city called "Shalem", which may or may not have been Jerusalem. The scenes of the great pharaoh and his army triumphing over the Hittite forces fleeing before Kadesh, as portrayed in the canons of the "epic poem of Pentaur", can still be seen on the pylon.

Only fragments of the base and torso remain of the syenite statue of the enthroned pharaoh, 62 feet (19 metres) high and weighing more than 1000 tons. This was alleged to have been transported 170 miles over land. This is the largest remaining colossal statue (except statues done in situ) in the world. However fragments of 4 granite Colossi of Ramses were found in Tanis (northern Egypt). Estimated height is 69 to 92 feet (21 to 28 meters). Like four of the six colossi of Amenhotep III (Colossi of Memnon) there are no longer complete remains so it is based partly on unconfirmed estimates.

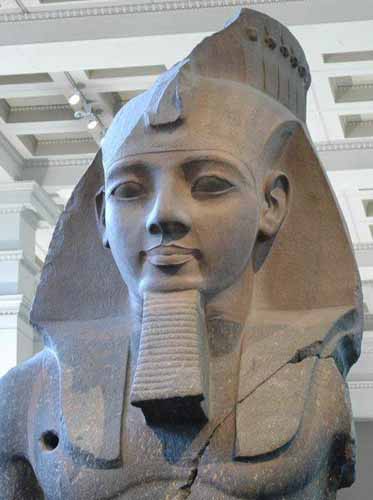

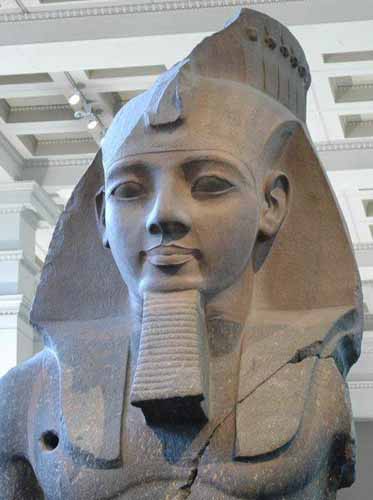

Remains of the second court include part of the internal facade of the pylon and a portion of the Osiride portico on the right. Scenes of war and the rout of the Hittites at Kadesh are repeated on the walls. In the upper registers, feast and honor of the phallic god Min, god of fertility. On the opposite side of the court the few Osiride pillars and columns still left can furnish an idea of the original grandeur. Scattered remains of the two statues of the seated king can also be seen, one in pink granite and the other in black granite, which once flanked the entrance to the temple. The head of one of these has been removed to the British Museum.

Thirty-nine out of the forty-eight columns in the great hypostyle hall (m 41x 31) still stand in the central rows. They are decorated with the usual scenes of the king before various gods. Part of the ceiling decorated with gold stars on a blue ground has also been preserved.

The sons and daughters of Ramesses appear in the procession on the few walls left. The sanctuary was composed of three consecutive rooms, with eight columns and the tetrastyle cell. Part of the first room, with the ceiling decorated with astral scenes, and few remains of the second room are all that is left.

Adjacent to the north of the hypostyle hall was a smaller temple; this was dedicated to Ramesses's mother, Tuya, and his beloved chief wife, Nefertari. To the south of the first courtyard stood the temple palace. The complex was surrounded by various storerooms, granaries, workshops, and other ancillary buildings, some built as late as Roman times.

A temple of Seti I, of which nothing is now left but the foundations, once stood to the right of the hypostyle hall. It consisted of a peristyle court with two chapel shrines. The entire complex was enclosed in mud brick walls which started at the gigantic southeast pylon.

A cache of papyri and ostraca dating back to the third intermediate period (11th to 8th centuries BC) indicates that the temple was also the site of an important scribal school.

The site was in use before Ramesses had the first stone put in place: beneath the hypostyle hall, modern archaeologists have found a shaft tomb from the Middle Kingdom, yielding a rich hoard of religious and funerary artifacts.

Unlike the massive stone temples that Ramesses ordered carved from the face of the Nubian mountains at Abu Simbel, the inexorable passage of three millennia was not kind to his "temple of a million years" at Thebes. This was mostly due to its location on the very edge of the Nile floodplain, with the annual inundation gradually undermining the foundations of this temple, and its neighbours. Neglect and the arrival of new faiths also took their toll: for example, in the early years of the Common Era, the temple was put into service as a Christian church.

This is all standard fare for a temple of its kind built at that time. Leaving aside the escalation of scale - whereby each successive New Kingdom pharaoh strove to outdo his predecessors in volume and scope - the Ramesseum is largely cast in the same mould as Ramesses III's Medinet Habu or the ruined temple of Amenhotep III that stood behind the "Colossi of Memnon" a kilometre or so away. Instead, the significance that the Ramesseum enjoys today owes more to the time and manner of its rediscovery by Europeans.

Pi-Ramesses (Pi-Ramesses Aa-nakhtu, meaning "House of Ramesses, Great in Victory") was the new capital built by the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt Pharaoh Ramesses II (Ramesses the Great, reigned 1279-1213 BC) at Qantir near the old site of Avaris. The city had previously served as a summer palace under Seti I (c. 1290 BC - 1279 BC) and may have been originally founded by Ramesses I (c. 1292-1290 BC) while he served under Horemheb.

When the ruins at Tanis were discovered in the 1930s by Pierre Montet their masses of broken Ramesside stonework led archaeologists to identify this as Pi-Ramesses, but it eventually came to be recognised that none of these monuments and inscriptions originated at the site.

In the 1960s Manfred Bietak, recognising that Pi-Ramesses was known to have been located on the then-easternmost branch of the Nile, painstakingly mapped all the branches of the ancient Delta and established that the Pelusiac branch was the easternmost during Ramesses' reign while the Tanitic branch (i.e. the branch on which Tanis was located) did not exist at all.

Excavations were therefore begun at the site of the highest Ramesside pottery location, Tell el-Dab'a and Qantir, and although there were no traces of any previous habitation visible on the surface, discoveries soon identified this as both the Hyksos capital Avaris and the Ramesside capital Pi-Ramesses. (Qantir, the site of Pi-Ramesses, lies some 30 kilometers to the south of Tanis; Tell el-Dab'a, the site of Avaris, is situated a little further south of Qantir).

Ramesses II was born and raised in the area, and family connections may have played a part in his decision to move his capital so far northward from the existing capital at Thebes; but geopolitical reasons may have been of greater importance, as Pi-Ramesses was much closer to the Egyptian vassal states in Asia and to the border with the hostile Hittite empire. Intelligence and diplomats would reach the Pharaoh much more quickly, and the main corps of the army were also encamped in the city and could quickly be mobilized to deal with incursions of Hittites or Shasu nomads from across the Jordan. Built on the banks of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile and with a population of over 300,000, making it one of the largest cities of ancient Egypt, Pi-Ramesses flourished for more than a century after Ramesses death and poems were written over its splendour. According to the latest estimates the city was spread over about 18 km2 (6.9 sq mi) or around 6 km (3.7 mi) long by 3 km (1.9 mi) wide. Its layout, as shown by ground-penetrating radar, consisted of a huge central temple, a large precinct of mansions bordering the river in the west set in a rigid grid pattern of streets, and a disorderly collection of houses and workshops in the east.

The palace of Ramesses is believed to lie beneath the modern village of Qantir. An Austrian team of archaeologists headed by Manfred Bietak, who discovered the site, found evidence of many canals and lakes and have described the city as the Venice of Egypt. A surprising discovery in the excavated stables were small cisterns located adjacent to each of the estimated 460 horse tether points. Using mules, which are the same size as the horses of Ramesses day, it was found a double tethered horse would naturally use the cistern as a toilet leaving the stable floor clean and dry.

It was originally thought the demise of Egyptian authority abroad during the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt made the city less significant leading to it being abandoned as a royal residence. It is now known that the Pelusiac branch of the Nile began silting up c. 1060 BC, leaving the city without water when the river eventually established a new course to the west now called the Tanitic branch.

The Twenty-first Dynasty of Egypt moved the city to the new branch establishing Djanet (Tanis) on its banks, 100 km (62 mi) to the north-west of Pi-Ramesses as the new capital of Lower Egypt. The Pharaohs of the Twenty-first Dynasty transported all the old Ramesside temples, obelisks, stelas, statues and sphinxes from Pi-Ramesses to the new site. The obelisks and statues, the largest weighing over 200 tons, were transported in one piece while major buildings were dismantled into sections and reassembled at Tanis. Stone from the less important buildings was reused and recycled for the creation of new temples and buildings.

The biblical Book of Exodus mentions "Ramesses" as one of the cities on whose construction the Israelites were forced to labour. Understandably, this Ramesses was identified by an early generation of biblical archaeolgists with the Pi-Ramesses of Ramesses II.

When the 21st Dynasty moved the capital to Tanis Pi-Ramesses was largely abandoned and the old capital became a quarry for ready-made monuments, but it was not forgotten: its name appears in a list of 21st Dynasty cities, and it had a revival under Sheshonq I (the biblical Shishak) of the 22nd Dynasty (10th century BC), who tried to emulate the achievements of Ramesses. The existence of the city as Egypt's capital as late as the 10th century makes problematic the reference to Ramesses in the Exodus story as a memory of the era of Ramesses II; and indeed, the shortened form "Ramesses", in place of the original Pi-Ramesses, is first found in 1st millennium texts.

The Bible describes Ramesses as a "store-city". The exact meaning of the Hebrew phrase is not certain, but some have suggested that it refers to supply depots on or near the frontier. This would be an appropriate description for Pithom (Tel al-Maskhuta) in the 6th century BC, but not for the royal capital in the time of Ramesses, when the nearest frontier was far off in the north of Syria. Only after the original royal function of Pi-Ramesses had been forgotten could the ruins have been re-interpreted as a fortress on Egypt's frontier.

On the other hand, Pi-Ramesses itself, during its construction in the 13th century BC under Ramesses II, absorbed the smaller palace-city of Avaris which indeed contained or had contained massive storage facilities--not for frontier storage but for trade. Therefore, while a store-city called Ramesses was not constructed anew, it remains that workers were employed in the monumental construction and re-construction that embraced Avaris, the store city, in the expansion of Pi-Ramesses.

As well as the famous temples of Abu Simbel, Ramesses left other monuments to himself in Nubia. His early campaigns are illustrated on the walls of Beit el-Wali (now relocated to New Kalabsha). Other temples dedicated to Ramesses are Derr and Gerf Hussein (also relocated to New Kalabsha).

Nefertari also known as Nefertari Merytmut was one of the Great Royal Wives (or principal wives) of Ramesses the Great. Nefertari means 'Beautiful Companion' and Meritmut means 'Beloved of the Goddess Mut'. She is one of the best known Egyptian queens, next to Cleopatra, Nefertiti and Hatshepsut. Her lavishly decorated tomb, QV66, is the largest and most spectacular in the Valley of the Queens. Ramesses also constructed a temple for her at Abu Simbel next to his colossal monument here.

Although Nefertari's origins are unknown, the discovery from her tomb of a knob inscribed with the cartouche of Pharaoh Ay has led people to speculate she was related to him. The time between the reign of Ay and Ramesses II means that Nefertari could not be a daughter of Ay and if any relation exists at all, she would be a great-granddaughter.

It is possible that Nefertari is either the daughter or granddaughter of Mutnodjemet, sister of Queen Nefertiti.There is no conclusive evidence linking Nefertari to the royal family of the 18th dynasty however. Nefertari married Ramesses II before he ascended the throne.

Nefertari had at least four sons and two daughters. Amun-her-khepeshef, the eldest was Crown Prince and Commander of the Troops, and Pareherwenemef would later serve in Ramesses II's army. Prince Meryatum was elevated to the position of High Priest of Re in Heliopolis. Inscriptions mention he was a son of Nefertari. Prince Meryre is a fourth son mentioned on the facade of the small temple at Abu Simbel and is thought to be another son of Nefertari. Meritamen and Henuttawy are two royal daughters depicted on the facade of the small temple at Abu Simbel and are thought to be daughters of Nefertari.

Princesses named Bak(et)mut, Nefertari, and Nebettawy are sometimes suggested as further daughters of Nefertari based on their presence in Abu Simbel, but there is no concrete evidence for this supposed family relation.

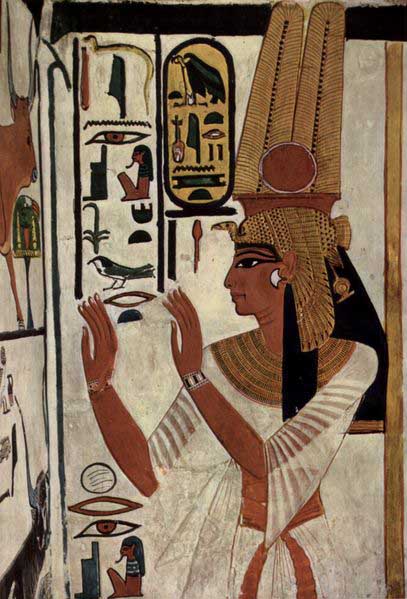

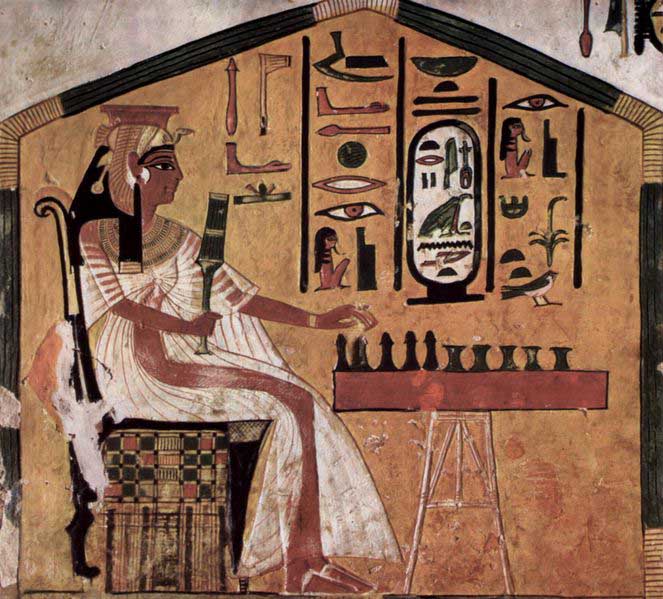

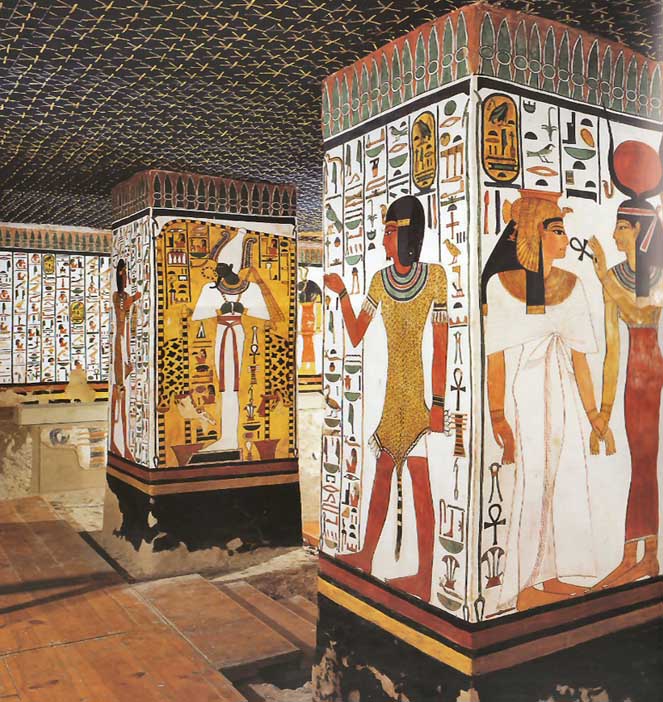

QV66 is the tomb of Nefertari, the Great Wife of Ramesses II, in Egypt's Valley of the Queens. It was discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli (the director of the Egyptian Museum in Turin) in 1904. It is called the Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt.

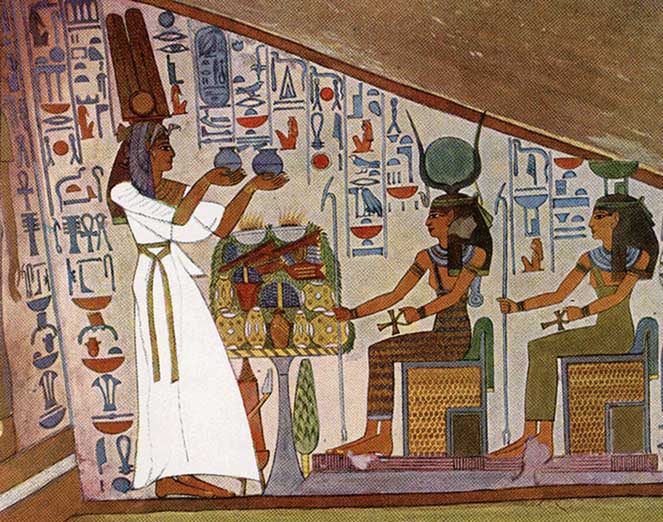

The most important and famous of Ramesses's consorts was discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1904. Although it had been looted in ancient times, the tomb of Nefertari is extremely important, because its magnificent wall painting decoration is regarded as one of the greatest achievements of ancient Egyptian art. A flight of steps cut out of the rock gives access to the antechamber, which is decorated with paintings based on chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead.

This astronomical ceiling represents the heavens and is painted in dark blue, with a myriad of golden five-pointed stars. The east wall of the antechamber is interrupted by a large opening flanked by representation of Osiris at left and Anubis at right; this in turn leads to the side chamber, decorated with offering scenes, preceded by a vestibule in which the paintings portray Nefertari being presented to the gods who welcome her.

On the north wall of the antechamber is the stairway that goes down to the burial chamber. This latter is a vast quadrangular room covering a surface area of about 90 square metres (970 sq ft), the astronomical ceiling of which is supported by four pillars entirely covered with decoration. Originally, the queen's red granite sarcophagus lay in the middle of this chamber.

According to religious doctrines of the time, it was in this chamber, which the ancient Egyptians called the golden hall that the regeneration of the deceased took place. This decorative pictogram of the walls in the burial chamber drew inspirations from chapters 144 and 146 of the Book of the Dead: in the left half of the chamber, there are passages from chapter 144 concerning the gates and doors of the kingdom of Osiris, their guardians, and the magic formulas that had to be uttered by the deceased in order to go past the doors.

A flight of steps cut out of the rock gives access to the antechamber, which is decorated with paintings based on Chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead. This astronomical ceiling represents the heavens and is painted in dark blue, with a myriad of golden five-pointed stars.

The east wall of the antechamber is interrupted by a large opening flanked by representation of Osiris at left and Anubis at right; this in turn leads to the side chamber, decorated with offering scenes, preceded by a vestibule in which the paintings portray Nefertari being presented to the gods who welcome her.

On the north wall of the antechamber is the stairway that goes down to the burial chamber. This latter is a vast quadrengular room covering a surface area about 90 square meters, the astronomical ceiling of which is supported by four pillars entirely covered with decoration. Originally, the queen's red granite sarcophagus lay in the middle of this chamber.

According to religious doctrines of the time, it was in this chamber, which the ancient Egyptians called the "golden hall" that the regeneration of the deceased took place. This decorative pictogram of the walls in the burial chamber drew inspirations from chapters 144 and 146 of the Book of the Dead: in the left half of the chamber, there are passages from chapter 144 concerning the gates and doors of the kingdom of Osiris, their guardians, and the magic formulas that had to be uttered by the deceased in order to go past the doors.

The tomb itself is primarily focused on two things, the first being the Queen's life and the second being her death.

Ramesses' obvious affection for his wife, as written on her tomb's walls, shows clearly that Egyptian queens were not simply marriages of convenience or marriages designed to accumulate greater power and alliances, but, in some cases at least, were actually based around some kind of emotional attachment.

Also poetry written by Ramesses about his dead wife is featured on some of the walls of her burial chamber.

Nefertari's origins are unknown except that is thought that she was a member of the nobility, although while she was queen her brother Amenmose held the position of Mayor of Thebes.

The real value of the paintings found within the tomb is that they are the best preserved and most detailed source of the ancient Egyptian's journey towards the afterlife. The tomb features several extracts from the Book of the Dead from chapters 148, 94, 146, 17 and 144 and tells of all the ceremonies and tests taking place from the death of Nefertari up until the end of her journey, depicted on the door of her burial chamber, in which Nefertari is reborn and emerges from the eastern horizon as a sun disc, forever immortalized in victory over the world of darkness.

The details of the ceremonies concerning the afterlife also tell us much about the duties and roles of many major and minor gods during the reign of the 19th Dynasty in the New Kingdom. Gods mentioned on the tomb walls include Isis, Osiris, Anubis, Hathor, Neith, Serket, Ma'at, Wadjet, Nekhbet, Amunet, Ra and Nephthys.

Unfortunately by the time that Schiaparelli rediscovered Nefertari's tomb it had already been found by tomb raiders, who had stolen all the treasure buried with the Queen, including her sarcophagus and mummy. Some pieces of the mummy were found in the burial chamber, and were taken to the Egyptian Museum in Turin by Schiaparelli, where they still reside today.

The tomb was closed to the public in 1950 because of various problems that threatened the spectacular paintings, which are considered to be the best preserved and most eloquent decorations of any Egyptian burial site, found on almost every available surface in the tomb, including stars painted thousands of times on the ceiling of the burial chamber on a blue background to represent the sky.

In 1986 an operation to restore all the paintings within the tomb was embarked upon by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization and the Getty Conservation Institute; however, work did not begin on the actual restoration until 1988 which was completed in April 1992. Upon completion of the restoration work, Egyptian authorities decided to severely restrict public access to the tomb in order to preserve the delicate paintings found within.

Early in his life, Ramesses II embarked on numerous campaigns to return previously held territories back from Nubian and Hittite hands and to secure Egypt's borders. He was also responsible for suppressing some Nubian revolts and carrying out a campaign in Libya. Although the famous Battle of Kadesh often dominates the scholarly view of Ramesses II's military prowess and power, he nevertheless enjoyed more than a few outright victories over the enemies of Egypt. During Ramesses II's reign, the Egyptian army is estimated to have totaled about 100,000 men; a formidable force that he used to strengthen Egyptian influence.

In his second year, Ramesses II decisively defeated the Shardana or Sherden sea pirates who were wreaking havoc along Egypt's Mediterranean coast by attacking cargo-laden vessels travelling the sea routes to Egypt. The Sherden people probably came from the coast of Ionia or possibly south-west Turkey.

Ramesses posted troops and ships at strategic points along the coast and patiently allowed the pirates to attack their prey before skillfully catching them by surprise in a sea battle and capturing them all in a single action. A stele from Tanis speaks of their having come "in their war-ships from the midst of the sea, and none were able to stand before them".

There must have been a naval battle somewhere near the mouth of the Nile, as shortly afterwards many Sherden are seen in the Pharaoh's body-guard where they are conspicuous by their horned helmets with a ball projecting from the middle, their round shields and the great Naue II swords with which they are depicted in inscriptions of the Battle of Kadesh. In that sea battle, together with the Shardana, the pharaoh also defeated the Lukka possibly the later Lycians), and the Shekelesh peoples.

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into Canaan and Palestine. His first campaign seems to have taken place in the fourth year of his reign and was commemorated by the erection of a stele near modern Beirut. The inscription is almost totally illegible due to weathering.

His records tell us that he was forced to fight a Palestinian prince who was mortally wounded by an Egyptian archer, and whose army was subsequently routed. Ramesses carried off the princes of Palestine as live prisoners to Egypt. Ramesses then plundered the chiefs of the Asiatics in their own lands, returning every year to his headquarters at Riblah to exact tribute. In the fourth year of his reign, he captured the Hittite vassal state of Amurru during his campaign in Syria.

The Battle of Kadesh in his fifth regnal year was the climactic engagement in a campaign that Ramesses fought in Syria, against the resurgent Hittite forces of Muwatallis. The pharaoh wanted a victory at Kadesh both to expand Egypt's frontiers into Syria and to emulate his father Seti I's triumphal entry into the city just a decade or so earlier. He also constructed his new capital, Pi-Ramesses where he built factories to manufacture weapons, chariots, and shields. Of course, they followed his wishes and manufactured some 1,000 weapons in a week, about 250 chariots in 2 weeks, and 1,000 shields in a week and a half. After these preparations, Ramesses moved to attack territory in the Levant which belonged to a more substantial enemy than any he had ever faced before: the Hittite Empire.

Although Ramesses's forces were caught in a Hittite ambush and outnumbered at Kadesh, the pharaoh fought the battle to a stalemate and returned home a hero. Ramesses II's forces suffered major losses particularly among the 'Ra' division which was routed by the initial charge of the Hittite chariots during the battle.

Once back in Egypt, Ramesses proclaimed that he had won a great victory. He had amazed everybody by almost winning a lost battle. The Battle of Kadesh was a personal triumph for Ramesses, as after blundering into a devastating Hittite ambush, the young king courageously rallied his scattered troops to fight on the battlefield while escaping death or capture. Still, many historians regard the battle as a strategic defeat for the Egyptians as they were unable to occupy the city or territory around Kadesh.

Ramesses decorated his monuments with reliefs and inscriptions describing the campaign as a whole, and the battle in particular as a major victory. Inscriptions of his victory decorate the Ramesseum, Abydos, Karnak, Luxor and Abu Simbel. For example, on the temple walls of Luxor the near catastrophe was turned into an act of heroism

Egypt's sphere of influence was now restricted to Canaan while Syria fell into Hittite hands. Canaanite princes, seemingly influenced by the Egyptian incapacity to impose their will, and goaded on by the Hittites, began revolts against Egypt. In the seventh year of his reign, Ramesses II returned to Syria once again. This time he proved more successful against his Hittite foes. During this campaign he split his army into two forces. One was led by his son, Amun-her-khepeshef, and it chased warriors of the Shasu tribes across the Negev as far as the Dead Sea, and captured Edom-Seir. It then marched on to capture Moab. The other force, led by Ramesses, attacked Jerusalem and Jericho. He, too, then entered Moab, where he rejoined his son. The reunited army then marched on Hesbon, Damascus, on to Kumidi, and finally recaptured Upi, reestablishing Egypt's former sphere of influence.

Ramesses extended his military successes in his eighth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (Nahr el-Kelb) and pushed north into Amurru. His armies managed to march as far north as Dapur,[ where he erected a statue of himself. The Egyptian pharaoh thus found himself in northern Amurru, well past Kadesh, in Tunip, where no Egyptian soldier had been seen since the time of Thutmose III almost 120 years earlier.

He laid siege to the city before capturing it. His victory proved to be ephemeral. In year nine, Ramesses erected a stele at Beth Shean. After having reasserted his power over Canaan, Ramesses led his army north. A mostly illegible stele near Beirut, which appears to be dated to the king's second year, was probably set up there in his tenth.

The thin strip of territory pinched between Amurru and Kadesh did not make for a stable possession. Within a year, they had returned to the Hittite fold, so that Ramesses had to march against Dapur once more in his tenth year. This time he claimed to have fought the battle without even bothering to put on his corslet until two hours after the fighting began. Six of Ramesses's sons, still wearing their side locks, took part in this conquest. He took towns in Retenu, and Tunip in Naharin, later recorded on the walls of the Ramesseum. This second success here was equally as meaningless as his first, as neither power could decisively defeat the other in battle.

The deposed Hittite king, Mursili III fled to Egypt, the land of his country's enemy, after the failure of his plots to oust his uncle from the throne. Hattusili III responded by demanding that Ramesses II extradite his nephew back to Hatti.

This demand precipitated a crisis in relations between Egypt and Hatti when Ramesses denied any knowledge of Mursili's whereabouts in his country, and the two Empires came dangerously close to war. Eventually, in the twenty-first year of his reign (1258 BC), Ramesses decided to conclude an agreement with the new Hittite king at Kadesh, Hattusili III, to end the conflict. The ensuing document is the earliest known peace treaty in world history.

The peace treaty was recorded in two versions, one in Egyptian hieroglyphs, the other in Akkadian, using cuneiform script; both versions survive. Such dual-language recording is common to many subsequent treaties. This treaty differs from others however, in that the two language versions are differently worded. Although the majority of the text is identical, the Hittite version claims that the Egyptians came suing for peace, while the Egyptian version claims the reverse. The treaty was given to the Egyptians in the form of a silver plaque, and this "pocket-book" version was taken back to Egypt and carved into the Temple of Karnak.

The treaty was concluded between Ramesses II and Hattusili III in Year 21 of Ramesses's reign. (c. 1258 BC) Its 18 articles call for peace between Egypt and Hatti and then proceeds to maintain that their respective gods also demand peace. The frontiers are not laid down in this treaty but can be inferred from other documents. The Anastasy A papyrus describes Canaan during the latter part of the reign of Ramesses II and enumerates and names the Phoenician coastal towns under Egyptian control. The harbour town of Sumur north of Byblos is mentioned as being the northern-most town belonging to Egypt, which points to it having contained an Egyptian garrison.

No further Egyptian campaigns in Canaan are mentioned after the conclusion of the peace treaty. The northern border seems to have been safe and quiet, so the rule of the pharaoh was strong until Ramesses II's death, and the waning of the dynasty.

When the King of Mira attempted to involve Ramesses in a hostile act against the Hittites, the Egyptian responded that the times of intrigue in support of Mursili III, had passed. Hattusili III wrote to Kadashman-Enlil II, King of Karduniash (Babylon) in the same spirit, reminding him of the time when his father, Kadashman-Turgu, had offered to fight Ramesses II, the king of Egypt.

The Hittite king encouraged the Babylonian to oppose another enemy, which must have been the king of Assyria whose allies had killed the messenger of the Egyptian king. Hattusili encouraged Kadashman-Enlil to come to his aid and prevent the Assyrians from cutting the link between the Canaanite province of Egypt and Mursili III, the ally of Ramesses.

Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract into Nubia. When Ramesses was about 22, two of his own sons, including Amun-her-khepeshef, accompanied him in at least one of those campaigns. By the time of Ramesses, Nubia had been a colony for two hundred years, but its conquest was recalled in decoration from the temples Ramesses II built at Beit el-Wali (which was the subject of epigraphic work by the Oriental Institute during the Nubian salvage campaign of the 1960s), Gerf Hussein and Kalabsha in northern Nubia. On the south wall of the Beit el-Wali temple, Ramesses II is depicted charging into battle against the Nubians in a war chariot, while his two young sons Amun-her-khepsef and Khaemwaset are shown being present behind him, also in war chariots. On one of the walls of Ramesses's temples it says that in one of the battles with the Nubians he had to fight the whole battle alone without any help from his soldiers.

During the reign of Ramesses II, there is evidence that the Egyptians were active on a 300-kilometre (190 mi) stretch along the Mediterranean coast, at least as far as Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. Although the exact events surrounding the foundation of the coastal forts and fortresses is not clear, some degree of political and military control must have been held over the region to allow their construction.

There are no detailed accounts of Ramesses II's undertaking large military actions against the Libyans, only generalized records of his conquering and crushing them, which may or may not refer to specific events that were otherwise unrecorded. It may be that some of the records, such as the Aswan Stele of his year 2, are harking back to Ramesses's presence on his father's Libyan campaigns. Perhaps it was Seti I who achieved this supposed control over the region, and who planned to establish the defensive system, in a manner similar to how he rebuilt those to the east, the Ways of Horus across Northern Sinai.

Ramesses was the pharaoh most responsible for erasing the Amarna Period from history. He, more than any other pharaoh, sought deliberately to deface the Amarna monuments and change the nature of the religious structure and the structure of the priesthood, in order to try to bring it back to where it had been prior to the reign of Akhenaten.

After reigning for 30 years, Ramesses joined a selected group that included only a handful of Egypt's longest-lived kings. By tradition, in the 30th year of his reign Ramesses celebrated a jubilee called the Sed festival, during which the king was ritually transformed into a god. Only halfway through what would be a 66-year reign, Ramesses had already eclipsed all but a few greatest kings in his achievements. He had brought peace, maintained Egyptian borders and built great and numerous monuments across the empire. His country was more prosperous and powerful than it had been in nearly a century. By becoming a god, Ramesses dramatically changed not just his role as ruler of Egypt, but also the role of his firstborn son, Amun-her-khepsef. As the chosen heir and commander and chief of Egyptian armies, his son effectively became ruler in all but name.

By the time of his death, aged about 90 years, Ramesses was suffering from severe dental problems and was plagued by arthritis and hardening of the arteries. He had made Egypt rich from all the supplies and riches he had collected from other empires. He had outlived many of his wives and children and left great memorials all over Egypt, especially to his beloved first queen Nefertari.

Nine more pharaohs took the name Ramesses in his honor, but none equalled his greatness. Nearly all of his subjects had been born during his reign. Ramesses II did become the legendary figure he so desperately wanted to be, but this was not enough to protect Egypt. New enemies were attacking the empire, which also suffered internal problems and could not last indefinitely.

Less than 150 years after Ramesses died the Egyptian empire fell and the New Kingdom came to an end.

Ramesses II was originally buried in the tomb KV7 in the Valley of the Kings but, because of looting, priests later transferred the body to a holding area, re-wrapped it, and placed it inside the tomb of queen Inhapy. 72 hours later it was again moved, to the tomb of the high priest Pinudjem II. All of this is recorded in hieroglyphics on the linen covering the body. His mummy is today in Cairo's Egyptian Museum.

The pharaoh's mummy reveals a hooked nose and strong jaw, and stands at some 1.7 metres (5 ft 7 in). His ultimate successor was his thirteenth son, Merneptah.

Ramesses II's sarcophagus finally identified thanks to overlooked hieroglyphics Live Science - May 28, 2024

Archaeologists determined that a fragment of a sarcophagus hidden beneath a Coptic building's floor once belonged to Ramesses II. A sarcophagus fragment discovered beneath the floor of a religious center belongs to Ramesses II, one of the best-known ancient Egyptian pharaohs, according to a new study. Archaeologists unearthed the granite artifact in 2009 inside a Coptic building in Abydos, an ancient city in east-central Egypt.

The team, led by archaeologists Ayman Damrani and Kevin Cahail, had determined that the sarcophagus had carried two individuals at different times. However, they could identify only the latter - Menkheperre, a "high priest of the 21st dynasty," who lived in roughly 1000 B.C., according to a translated statement from France's National Center for Scientific Research. The initial owner of the sarcophagus - a container that is covered in carved decorations and texts - had remained a mystery. But archaeologists knew it had belonged to a "very high-ranking figure of the Egyptian New Kingdom," according to the statement.

Ancient Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II's 'handsome' face revealed in striking reconstruction Live Science - January 11, 2023

Scientists have used facial reconstruction techniques to show what the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II looked like in his prime. The face of the ancient Egyptian ruler Ramesses II - possibly the pharaoh of the biblical Book of Exodus who persecuted Moses and the Israelites - has been reconstructed from his mummified remains. And although the pharaoh died in his 90s, his visage has been "reverse aged" by several decades to show him in his prime, at about age 45.

Lost temple of Ramses II is discovered in Giza: Incredible find sheds light on the ruler who fathered more children than any other pharaoh Daily Mail - October 16, 2017

The lost temple of Ramses II has been uncovered by archaeologists, shedding light one of Egypt's most revered leaders. Among the 3,200-year-old ruins, researchers uncovered motifs devoted to ancient Egyptian sun gods - giving a unique insight into who he worshipped. The temple, which was uncovered in the Abusir Necropolis in Giza, measures around 110 feet in width and 170 feet (34 by 52 metres) in length.

Massive Ancient Statue of Ramses II Discovered Submerged In Mud In Cairo NPR - March 10, 2017

Archaeologists working under difficult conditions in Cairo have discovered an ancient statue submerged in mud. A joint German-Egyptian research team found the 8-meter (26-foot) quartzite statue beneath the water level in a Cairo slum and suggests that it depicts Ramses II, according to Reuters. The team was working at what was once Heliopolis, one of the oldest cities in ancient Egypt and the cult center for the sun god. Khaled al-Anani, Egypt's antiquities minister, posted on Facebook that one of the researchers who found the statue called it "one of the most important archaeological discoveries."