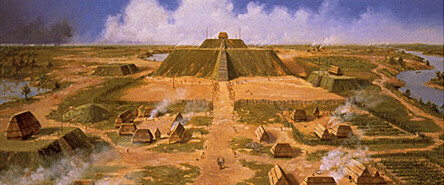

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site is located on the site of an ancient Native American city (c. 600-1400 CE) situated directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in southern Illinois between East St. Louis and Collinsville. The park covers 2,200 acres (890 ha), or about 3.5 square miles, and contains about 80 mounds, but the ancient city was actually much larger. In its heyday, Cahokia covered about six square miles and included about 120 human-made earthen mounds in a wide range of sizes, shapes, and functions.

Cahokia was the largest and most influential urban settlement in the Mississippian culture which developed advanced societies across much of what is now the Southeastern United States, beginning more than 500 years before European contact. Cahokia's population at its peak in the 1200s was among the largest cities in the world, and its ancient population would not be surpassed by any city in the United States until the late 18th century. Today, Cahokia Mounds is considered the largest and most complex archaeological site north of the great Pre-Columbian cities in Mexico.

Cahokia Mounds is a National Historic Landmark and designated site for state protection. In addition, it is one of only 21 World Heritage Sites within the United States. It is the largest prehistoric earthen construction in the Americas north of Mexico. The site is open to the public and administered by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, and is supported by the Cahokia Mounds Museum Society.

Although there is some evidence of Late Archaic period (approximately 1200 BCE) occupation in and around the site, Cahokia as it is now defined was settled around 600 CE during the Late Woodland period.

Mound building at this location began with the Emergent Mississippian cultural period, about the 9th century CE. The inhabitants left no written records beyond symbols on pottery, shell, copper, wood and stone, but the elaborately planned community, woodhenge, mounds and burials reveal a complex and sophisticated society. The city's original name is unknown.

The original site contained 120 earthen mounds over an area of six square miles, of which 80 remain today. To achieve that, thousands of workers over decades moved more than an "estimated 55 million cubic feet of earth in woven baskets to create this network of mounds and community plazas. Monks Mound, for example, covers 14 acres (5.7 ha), rises 100 ft (30 m), and was topped by a massive 5,000 sq ft (460 m2) building another 50 ft (15 m) high."

The Mounds were later named after the Cahokia tribe, an historic Illiniwek people living in the area when the first French explorers arrived in the 17th century. As this was centuries after Cahokia was abandoned by its original inhabitants, the Cahokia tribe was not necessarily descendants of the original Mississippian-era people. Most likely multiple ethnic groups settled Cahokia. Though widely debated, some archaeologists connect Dhegihan Siouan-speaking tribes to Cahokia. They include the Osage, Kaw, Omaha, Ponca, and Quapaw. Many Native American tribes migrated over the centuries, and those living in territories at the time of European encounter were often not the descendants of peoples who had lived there before.

Cahokia began to decline after AD 1300. It was abandoned more than a century before Europeans arrived in North America, in the early 16th century, and the area around it was largely uninhabited by indigenous tribes Scholars have proposed environmental factors, such as over-hunting and deforestation as explanations.

The houses, stockade, and residential and industrial fires would have required the annual harvesting of thousands of logs. In addition, climate change could have aggravated effects of erosion due to deforestation, and adversely affected the cultivation of maize, on which the community had depended.

Another possible cause is invasion by outside peoples, though the only evidence of warfare found so far is the wooden stockade and watchtowers that enclosed Cahokia's main ceremonial precinct. Due to the lack of other evidence for warfare, the palisade appears to have been more for ritual or formal separation than for military purposes. Diseases transmitted among the large, dense urban population are another possible cause of decline. Many recent theories propose conquest-induced political collapse as the primary reason for Cahokia's abandonment.

Cahokia was the most important center for the peoples known today as Mississippians. Their settlements ranged across what is now the Midwest, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. Cahokia was located in a strategic position near the confluence of the Mississippi, Missouri and Illinois rivers. It maintained trade links with communities as far away as the Great Lakes to the north and the Gulf Coast to the south, trading in such exotic items as copper, Mill Creek chert, and whelk shells.

Mill Creek chert, most notably, was used in the production of hoes, a high demand tool for farmers around Cahokia and other Mississippian centers. Cahokia's control of the manufacture and distribution of these hand tools was an important economic activity that allowed the city to thrive. Mississippian culture pottery and stone tools in the Cahokian style were found at the Silvernale site near Red Wing, Minnesota, and materials and trade goods from Pennsylvania, the Gulf Coast and Lake Superior have been excavated at Cahokia.

At the high point of its development, Cahokia was the largest urban center north of the great Mesoamerican cities in Mexico. Although it was home to only about 1,000 people before c. 1050, its population grew explosively after that date. Archaeologists estimate the city's population at between 6,000 and 40,000 at its peak, with more people living in outlying farming villages that supplied the main urban center. If the highest population estimates are correct, Cahokia was larger than any subsequent city in the United States until the 1780s, when Philadelphia's population grew beyond 40,000.

One of the major problems that large centers like Cahokia faced was keeping a steady supply of food, and waste disposal was also an issue, which made Cahokia an unhealthy place. Because it was such an unhealthy place to live, the town had to rely on social and political attractions to bring in a steady supply of new immigrants; otherwise the town's death rate would have caused it to be abandoned earlier.

The Lost City of Cahokia Was Mysteriously Abandoned, And We Still Don't Know Why Science Alert - January 31, 2022

For a couple of hundred years, Cahokia was the place to be in what is now the US state of Illinois. The bustling, vibrant city was at one time home to some 15,000 people, but by the end of the 14th century it was deserted - and researchers still aren't sure why. A study published last year was at least able to rule out one previous idea - that deforestation and overuse of the land around Cahokia caused excessive erosion and local flooding in the area, making it less inhabitable for Native Americans. Through an analysis of sediment cores gathered near earthen mounds in the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, researchers established that the ground remained stable from Cahokia's heyday until the mid-1800s and industrial development. In other words, there was no environmental disaster.

Cahokia remains a fascinating topic for experts, with a study published in 2020 that analyzed ancient human feces to suggest people had begun to return to Cahokia in substantial numbers well before European settlers started arriving in the 16th century. It's possible that the desertion of the metropolis didn't actually last that long. The mess we're making of looking after the planet at the moment makes it easier to imagine ecocide being responsible for some of the unexplained mysteries of the past, the team behind the 2021 study says - but it's important to keep digging to find the hard evidence as to what has actually happened.

White Settlers Buried the Truth About the Midwest's Mysterious Mound Cities Smithsonian - February 25, 2018

Pioneers and early archaeologists credited distant civilizations, not Native Americans, with building these sophisticated complexes. The city of Cahokia is one of many large earthen mound complexes that dot the landscapes of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys and across the Southeast. Despite the preponderance of archaeological evidence that these mound complexes were the work of sophisticated Native American civilizations, this rich history was obscured by the Myth of the Mound Builders, a narrative that arose ostensibly to explain the existence of the mounds. Examining both the history of Cahokia and the historic myths that were created to explain it reveals the troubling role that early archaeologists played in diminishing, or even eradicating, the achievements of pre-Columbian civilizations on the North American continent, just as the U.S. government was expanding westward by taking control of Native American lands.

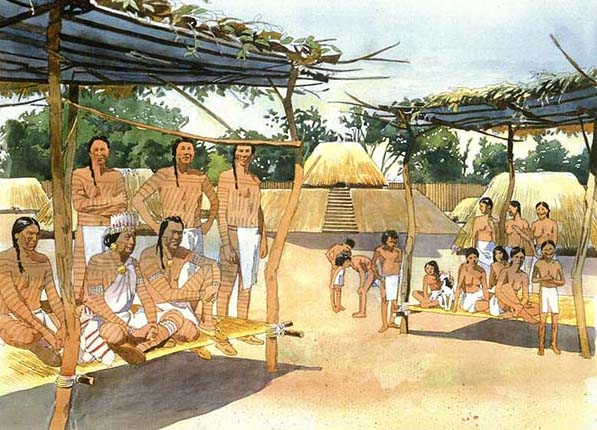

Today it's difficult to grasp the size and complexity of Cahokia, composed of about 190 mounds in platform, ridge-top, and circular shapes aligned to a planned city grid oriented five degrees east of north. This alignment, according to Tim Pauketat, professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois, is tied to the summer solstice sunrise and the southern maximum moonrise, orientating Cahokia to the movement of both the sun and the moon. Neighborhood houses, causeways, plazas, and mounds were intentionally aligned to this city grid. Imagine yourself walking out from Cahokia's downtown; on your journey you would encounter neighborhoods of rectangular, semi-subterranean houses, central hearth fires, storage pits, and smaller community plazas interspersed with ritual and public buildings. We know Cahokia's population was diverse, with people moving to this city from across the mid-continent, likely speaking different dialects and bringing with them some of their old ways of life.

Native American city on the Mississippi was America's first 'melting pot' PhysOrg - March 4, 2014

New evidence establishes for the first time that Cahokia, a sprawling, pre-Columbian city situated at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, hosted a sizable population of immigrants. Researchers have traditionally thought of Cahokia as a relatively homogeneous and stable population drawn from the immediate area. Increasingly archaeologists are realizing that Cahokia at AD 1100 was very likely an urban center with as many as 20,000 inhabitants. Such early centers around the world grow by immigration, not by birthrate. By analyzing the teeth of those buried in different locations in Cahokia, they discovered that immigrants formed one-third of the population of the city throughout its history (from about AD 1050 through the early 1300s).

The First US City Was Full of Immigrants Live Science - March 7, 2014

A sprawling city in the heartland of the United States was a cultural melting pot hundreds of years before Europeans ever set foot in North America. A study of dozens of teeth found at Cahokia, an ancient metropolis near modern-day St. Louis, shows that immigrants moved to the city from across the Midwest and perhaps as far away as the Great Lakes and Gulf Coast regions. Cahokia rose to prominence around A.D. 1050, when it underwent what some archaeologists call a cultural Big Bang.

The varying cultures collectively called Mound Builders were prehistoric inhabitants of North America who, during a 5,000-year period, constructed various styles of earthen mounds for religious and ceremonial, burial, and elite residential purposes. These included the Pre-Columbian cultures of the Archaic period; Woodland period (Adena and Hopewell cultures); and Mississippian period; dating from roughly 3400 BCE to the 16th century CE, and living in regions of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River valley, and the Mississippi River valley and its tributaries. Beginning with the construction of Watson Brake about 3400 BCE in present-day Louisiana, nomadic indigenous peoples started building earthwork mounds in North America nearly 1000 years before the pyramids were constructed in Egypt.

Since the 19th century, the prevailing scholarly consensus has been that the mounds were constructed by indigenous peoples of the Americas, early cultures distinctly separate from the historical Native American tribes extant at the time of European colonization of North America. The historical Native Americans were generally not knowledgeable about the civilizations that produced the mounds. Research and study of these cultures and peoples has been based on archaeology and anthropology.

Mound Builder or Mound People is a general term referring to the Native North American peoples who constructed various styles of earthen mounds for burial, residential, and ceremonial purposes. These included Archaic, and Woodland period, and Mississippian period Pre-Columbian cultures.

The term Mound Builder was also applied to an imaginary race believed to have constructed the great earthworks of the United States, this while Euro-american racial ideology of the 16th-19th centuries did not recognize that Native Americans were sophisticated enough to construct such monumental architecture.

The final blow to this myth was dealt by an official appointee of the United States Government, Cyrus Thomas of the Bureau of American Ethnology. His lengthy report (727 pages, published in 1894) concluded finally that it was the opinion of himself and thus the United States Government that the prehistoric earthworks of the eastern United States were the work of Native Americans. Thomas Jefferson was an early proponent of this view after he excavated a mound and ascertained the continuity of burial practices observed in contemporaneous native populations.

Poverty Point in what is now Louisiana is a prominent example of early archaic Mound Builder construction from about 2500 BC. While other and earlier Archaic mound centers existed, Poverty Point remains one of the best recognized centers. Throughout the United States, the Archaic period was followed by the Woodland period, and mound building continued.

Some well understood examples would be the Adena culture of Ohio and nearby states, and the subsequent Hopewell culture known from Illinois to Ohio and renowned for their geometric earthworks. The Adena and Hopewell were not, however, the only mound building peoples during this time period. There were contemporaneous mound building cultures throughout the Eastern United States.

Around 900-1000 AD the Mississippian culture developed and spread through Eastern United States, primarily along the river valleys. The major location where the Mississippian culture is clearly developed is located in Illinois, and is referred to today as Cahokia.

The namesake cultural trait of the Mound Builders was the building of mounds and other earthworks. These burial and ceremonial structures were typically flat-topped pyramids, flat-topped or rounded cones, elongated ridges, and sometimes a variety of other forms.

Some mounds took on unusual shapes, such as the outline of cosmologically significant animals. These are considered to be distinct and are known as effigy mounds.

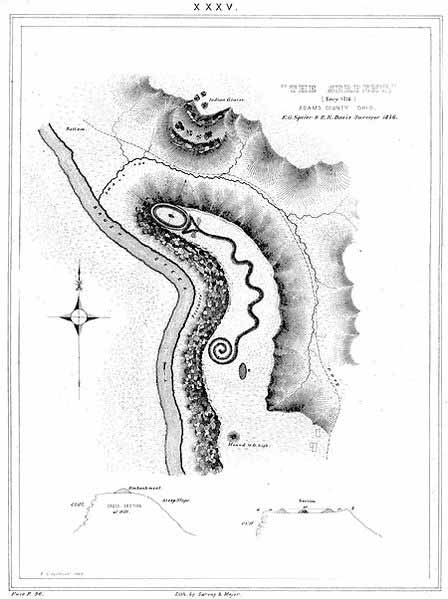

The best known flat-topped pyramidal earthen structure, which is also the largest pre-Columbian earthwork north of Mexico at over 100 feet tall, is Monk's Mound at Cahokia. The most famous effigy mound, Serpent Mound in southern Ohio, is 5 feet tall, 20 wide, over 1330 feet long, and shaped as a serpent.

The most complete reference for these earthworks is Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, written by Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin H. Davis and published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1848. Since a large number of the features they documented have since been destroyed or diminished by farming and development, their surveys, sketches and descriptions are still used by modern archaeologists. A smaller regional study in 1931 by author and archaeologist Fred Dustin charted and examined the mounds and Ogemaw Earthworks near Saginaw, Michigan.

The mound builders included many different tribal groups and chiefdoms, probably involving a bewildering array of beliefs and unique cultures, united only by the shared architectural practice of mound construction. This practice, believed to be associated with a cosmology that had a cross-cultural appeal, may indicate common cultural antecedents. The first mound building is an early marker of incipient political and social complexity among the cultures in the Eastern United States.

As with other continents, the mounds and pyramids of North America vary greatly. It could be that humankind has a primal need to build fake mountains, and that there are absolutely no connections between these sites. Perhaps size and shape are irrelevant, and location is everything, and the guidelines for their placement was once universally known.

It is difficult to determine how many mounds were built in North America, for many have been destroyed by modern civilization - but there were thousands.

Monks Mound is the largest Pre-Columbian earthwork in America north of Mesoamerica. Located at the Cahokia Mounds UNESCO World Heritage Site near Collinsville, Illinois, its size was calculated in 1988 as about 100 feet (30 m) high, 955 feet (291 m) long including the access ramp at the southern end, and 775 feet (236 m) wide. This makes Monks Mound roughly the same size at its base as the Great Pyramid of Giza (13.1 acres / 5.3 hectares). Its base circumference is larger than the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan.

Unlike Egyptian pyramids which were built of stone, the platform mound was constructed almost entirely of layers of basket-transported soil and clay. Because of this construction and its flattened top, over the years, it has retained rainwater within the structure. This has caused "slumping", the avalanche-like sliding of large sections of the sides at the highest part of the mound. Its designed dimensions would have been significantly smaller than its present extent, but recent excavations have revealed that slumping was a problem even while the mound was being made.

Construction of Monks Mound by the Mississippian culture began about 900-950 CE, on a site which had already been occupied by buildings. The original concept seems to have been a much smaller mound, now buried deep within the northern end of the present structure. At the northern end of the summit plateau, as finally completed around 1100 CE, is an area raised slightly higher still, on which was placed a building over 100 ft (30 m) long, the largest in the entire Cahokia Mounds urban zone.

Deep excavations in 2007 confirmed findings from earlier test borings, that several types of earth and clay from different sources had been used successively. Study of various sites suggests that the stability of the mound was improved by the incorporation of bulwarks, some made of clay, others of sods from the Mississippi flood-plain, which permitted steeper slopes than the use of earth alone.

The most recent section of the mound, added some time before 1200 CE, is the lower terrace at the south end, which was added after the northern end had reached its full height. It may partly have been intended to help minimize the slumping which by then was already under way.

Today, the western half of the summit plateau is significantly lower than the eastern; this is the result of massive slumping, beginning about 1200 CE. This also caused the west end of the big building to collapse. It may have led to the abandonment of the mound's high status, following which various wooden buildings were erected on the south terrace, and garbage was dumped at the foot of the mound. By about 1300, the urban society at Cahokia Mounds was in serious decline. When the eastern side of the mound started to suffer serious slumping, it was not repaired.

The Grand Plaza is a large open plaza that spreads out to the south of Monks Mound. Researchers originally thought the flat, open terrain in this area reflected Cahokia's location on the Mississippi's alluvial flood plain but instead soil studies have shown that the landscape was originally undulating. In one of the earliest large-scale construction projects, the site had been expertly and deliberately leveled and filled by the city's inhabitants. It is part of the sophisticated engineering displayed throughout the site. The Grand Plaza covered roughly 50 acres (20 ha) and measured over 1,600 ft (490 m) in length by over 900 ft (270 m) in width. It was used for large ceremonies and gatherings, as well as for ritual games, such as chunkey. Along with the Grand Plaza to the south, three other very large plazas surround Monks Mound in the cardinal directions to the east, west, and north.

The high-status district of Cahokia was surrounded by a long palisade that was equipped with protective bastions. Where the palisade passed, it separated neighborhoods. Archaeologists found evidence of the stockade during excavation of the area and indications that it was rebuilt several times. Its bastions showed that it was mainly built for defensive purposes.

Beyond Monks Mound, as many as 120 more mounds stood at varying distances from the city center. To date, 109 mounds have been located, 68 of which are in the park area. The mounds are divided into several different types: platform, conical, ridge-top, etc.. Each appeared to have had its own meaning and function. In general terms, the city center seems to have been laid out in a diamond-shaped pattern approximately 1 mi (1.6 km) from end to end, while the entire city is 5 mi (8.0 km) across from east to west.

The reconstructed Woodhenge, erected in 1985.

Archaeologists discovered postholes during excavation of the site to the west of Monks Mound, revealing a timber circle. Noting that the placement of posts marked solstices and equinoxes, they referred to it as "an American Woodhenge", likening it to England's well-known circles at Woodhenge and Stonehenge.[ Detailed analytical work supports the hypothesis that the placement of these posts was by design. The structure was rebuilt several times during the urban center's roughly 300-year history. Evidence of another timber circle was discovered near Mound 72, to the south of Monks Mound.

According to Chappell, "A beaker found in a pit near the winter solstice post bore a circle and cross symbol that for many Native Americans symbolizes the Earth and the four cardinal directions. Radiating lines probably symbolized the sun, as they have in countless other civilizations." The woodhenges were significant to the timing of the agricultural cycle.

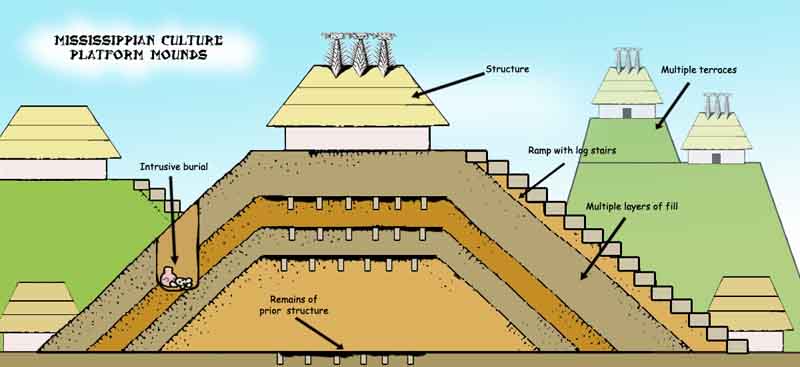

A platform mound is any earthwork or mound intended to support a structure or activity. The indigenous peoples of North America built substructure mounds for well over a thousand years starting in the Archaic period and continuing through the Woodland period. Many different archaeological cultures (Poverty Point culture, Troyville culture, Coles Creek culture, Plaquemine culture and Mississippian culture) of North Americas Eastern Woodlands are specifically well known for using platform mounds as a central aspect of their overarching religious practices and beliefs.

These platform mounds are usually four-sided truncated pyramids, steeply sided, with steps built of wooden logs ascending one side of the earthworks. When European first arrived in North America, the peoples of the Mississippian culture were still using and building platform mounds. Documented uses for Mississippian platform mounds include semi-public chief's house platforms, public temple platforms, mortuary platforms, charnel house platforms, earth lodge/town house platforms, residence platforms, square ground and rotunda platforms, and dance platforms.

Many of the mounds underwent multiple episodes of mound construction, with the mound becoming larger with each event. The site of a mound was usually a site with special significance, either a pre-existing mortuary site or civic structure. This site was then covered with a layer of basket-transported soil and clay known as mound fill and a new structure constructed on its summit.

At periodic intervals averaged about twenty years these structures would be removed, possibly ritually destroyed as part of renewal ceremonies, and a new layer of fill added, along with a new structure on the now higher summit. Sometimes the surface of the mounds would get a several inches thick coat of brightly colored clay. These layers also incorporated layers of different kinds of clay, soil and sod, an elaborate engineering technique to forestall slumping of the mounds and to ensure their steep sides did not collapse. This pattern could be repeated many times during the life of a site. The large amounts of fill needed for the mounds left large holes in the landscape now known by archaeologists as "borrow pits". These pits were sometimes left to fill with water and stocked with fish.

Some mounds were developed with separate levels (or terraces) and aprons, such as Emerald Mound, which is one large terrace with two smaller mounds on its summit; or Monks Mound, which has four separate levels and stands close to 100 feet (30 m) in height. Monks Mound had at least ten separate periods of mound construction over a 200-year period. Some of the terraces and aprons on the mound seem to have been added to stop slumping of the enormous mound. Although the mounds were primarily meant as substructure mounds for buildings or activities, sometimes burials did occur. Intrusive burials occurred when a grave was dug into a mound and the body or a bundle of defleshed, disarticulated bones was deposited into it.

Mound C at Etowah Mounds has been found to have more than 100 intrusive burials into the final layer of the mound, with many grave goods such as Mississippian copper plates (Etowah plates), monolithic stone axes, ceremonial pottery and carved whelk shell gorgets. Also interred in this mound was a paired set of white marble Mississippian stone statues.

A long-standing interpretation of Mississippian mounds comes from Vernon James Knight, who stated that the Mississippian platform mounds were one of the three "sacra", or objects of sacred display, of the Mississippian religion - also see Earth/fertility cult and Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. His logic is based on analogy to ethnographic and historic data on related Native American tribal groups in the Southeastern United States.

Knight suggests a microcosmic ritual organization based around a "native earth" autochthony, agriculture, fertility, and purification scheme, in which mounds and the site layout replicate cosmology. Mound rebuilding episodes are construed as rituals of burial and renewal, while the four-sided construction acts to replicate the flat earth and the four quarters of the earth.

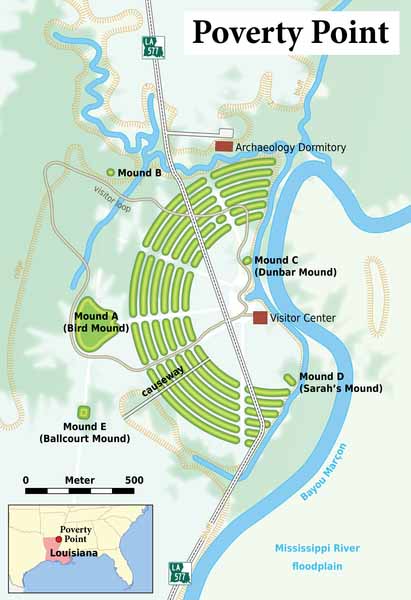

Poverty Point combines mounds with an aspect of ancient Rome - an amphitheatre. Consisting of concentric ridges 5-10 feet high and 150 wide, the construction has a diameter of 3-4 of a mile, five times the diameter of the Colosseum in Rome. The ridges were built with 530,000 cubic yards of earth (over 35 times the cubic amount of the Great Pyramid of Giza). Of the earth mounds, one has a base of 700 feet by 800 feet and is 70 feet high. It is shaped like a bird.

Poverty Point is a prehistoric earthworks of the Poverty Point culture, now a historic monument located in the Southern United States. It is 15.5 miles (24.9 km) from the current Mississippi River, and situated on the edge of Macon Ridge, near the village of Epps in West Carroll Parish, Louisiana.

Poverty Point comprises several earthworks and mounds built between 1650 and 700 BCE, during the Archaic period in the Americas by a group of Native Americans of the Poverty Point culture. The culture extended 100 miles (160 km) across the Mississippi Delta. The original purposes of Poverty Point have not been determined by archaeologists, although they have proposed various possibilities including that it was: a settlement, a trading center, and/or a ceremonial religious complex.

Mound A (The Bird Mound)

Alongside these ridges are other earthworks, primarily platform mounds. The largest of these, Mound A, is to the west of the ridges, and is roughly T-shaped when viewed from above. Many have interpreted it as being in the shape of a bird and also as an "Earth island", representing the cosmological center of the site.[4] Scholars use the fact that Mound A is in the center of a direct alignment between Mound B and E as an element demonstrating the complex planning exercised by the sites' builders.

Researchers have learned that Mound A was constructed quickly, probably over a period of less than three months. Prior to construction, the vegetation covering the site was burned. According to radiocarbon analysis, this burning occurred between approximately 1450 and 1250 BCE. Workers immediately covered the area with a cap of silt, followed quickly by the main construction effort. There are no signs of construction phases or weathering of the mound fill even at microscopic levels, indicating that construction proceeded in a single massive effort over a short period. In total volume, Mound A is made up of approximately 238,000 cubic meters of fill, making it the second-largest earthen mound (by volume) in eastern North America. It is second in overall size to the later Mississippian-culture Monks Mound at Cahokia, built beginning about 950-1000 CE in present-day Illinois.

Mound B

Mound B, a platform mound, is north-west of the rings. Below the mound was found a human bone interred with ashes, a likely indication of cremation, suggesting that this might have been a burial mound or the individual was a victim of human sacrifice. Mound B aligns in a straight north to south line with both mounds A and E.

Mound E (Ballcourt Mound)

The Ballcourt Mound, which is also a platform mound, is so called because "two shallow depressions on its flattened top reminded some archaeologists of playing areas in front of outdoor basketball goals, not because they had any revelation about Poverty Point's sports scene."

Mound E forms a north-south line with mounds A and B.

Dunbar and Lower Jackson mounds

Within the enclosure created by the curving earthworks, two additional platform mounds were located. The Dunbar Mound, had various pieces of chipped precious stones upon it, indicating that people used to sit atop it and make jewelry. South of the site center is the Lower Jackson Mound, which is believed to be the oldest of all the earthworks at the site. In the southern edge of the site, the Motley Mound rises 51 ft (16 m). The conical mound is circular and reaches a height of 24.5 ft (7.5 m). These three platform mounds are much smaller than the other mounds.

Theories

Some followers of the New Age movement believe the site has spiritual qualities. John Ward, in his controversial pseudo-archaeological Ancient Archives among the Cornstalks (1984), claimed that Poverty Point was built by refugees who fled up the Mississippi River after their home, Atlantis, was destroyed in 1198 BCE. A similar connection to the legendary lost city was made by Frank Joseph, who claimed that individuals who were the reincarnation of former Atlanteans were able to unleash the psychic energies of Poverty Point by spilling purified water on the oak tree upon the main mound at the site. Erich Von Daniken has suggested a connection to extraterrestrials. He suggested that one of the mounds was a landing platform for alien aircraft.

Archaic Native Americans built massive Louisiana mound in fewer than 90 days, research confirms PhysOrg - January 30, 2013

Nominated early this year for recognition on the UNESCO World Heritage List, which includes such famous cultural sites as the Taj Mahal, Machu Picchu and Stonehenge, the earthen works at Poverty Point, La., have been described as one of the world's greatest feats of construction by an archaic civilization of hunters and gatherers. Now, new research in the current issue of the journal Geoarchaeology, offers compelling evidence that one of the massive earthen mounds at Poverty Point was constructed in less than 90 days, and perhaps as quickly as 30 days - an incredible accomplishment for what was thought to be a loosely organized society consisting of small, widely scattered bands of foragers.

Etowah Mounds is a 54-acre (220,000 sq. miles) archaeological site in Bartow County, Georgia south of Cartersville, in the United States. Built and occupied in three phases, from 1000Ð1550 CE, the prehistoric site is located on the north shore of the Etowah River. Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site is a designated National Historic Landmark, managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. It is the most intact Mississippian culture site in the Southeastern United States.

These were made during the same Mississippian Temple Mound Building Period, as were mounds at Moundville (near Tuscaloosa, Alabama) and at Cahokia - roughly 700 AD to 1400 AD.

The six flat-topped earthen knolls and a plaza were used for rituals by several thousand Native Americans between 1000 and 1500 A.D. The largest mound has a height of 63 feet. Only nine percent of this site has been excavated, but we already know that the mounds have caves underneath them as do some Mayan and Giza pyramids.

It may also just be a coincidence, but there is a Limonite mine at Etowah. Limonite is a iron-bearing ore with a very special use - as radiation shielding for atomic bomb tests, nuclear reactors and space stations. It is also what gives Mars its red color.

Etowah has three main platform mounds and three lesser mounds. The Temple Mound, Mound A, is 63 feet (19 m) high, taller than a six-story building, and covers 3 acres (12,000 m2) at its base.

In 2005-2008 ground mapping with magnetometers revealed new information and data, showing that the site was much more complex than had previously been believed. The study team has identified a total of 140 buildings on the site. In addition, Mound A was found to have had four major structures and a courtyard at the height of the community's power.

Mounds A and B as seen from Mound C

Mound B is 25 feet (7.6 m) high; Mound C, which rises 10 feet (3.0 m), is the only one to have been completely excavated. Magnetometers enabled archaeologists to determine the location of temples of log and thatch, which were originally built on top of the mounds. Adjacent to the mounds is a raised ceremonial plaza, which was used for ceremonies, stickball and chunkey games, and as a bazaar for trade goods.

When visiting the Etowah Mounds, guests can view the "borrow pits" (which archaeologists at one time thought were moats) which were dug out to create the three large mounds in the center of the park.

Older pottery found on the site suggest that there was an earlier village (ca. 200 BCE-600 CE) associated with the Swift Creek culture. This earlier Middle Woodland period occupation at Etowah may have been related to the major Swift Creek center of Leake Mounds, approximately two miles downstream (west) of Etowah.

War was commonplace; many archaeologists believe the people of Etowah battled for hegemony over the Alabama river basin with those of Moundville, a Mississippian site in present-day Alabama. The town was protected by a sophisticated semicircular fortification system. An outer band formed by nut tree orchards prevented enemy armies from shooting masses of flaming arrows into the town. A 9 feet (2.7 m) to 10 feet (3.0 m) deep moat blocked direct contact by the enemy with the palisaded walls.

It also functioned as a drainage system during major floods, common for centuries, from this period and into the 20th century. Workers formed the palisade by setting upright 12 feet (3.7 m) high logs into a ditch approximately 12 inches (300 mm) on center and then back-filling around the timbers to form a levee. Guard towers for archers were spaced approximately 80 feet (24 m) apart.

Etowah Birdman

The artifacts discovered in burials within the Etowah site indicate that its residents developed an artistically and technically advanced culture. Numerous copper tools, weapons and ornamental copper plates accompanied the burials of members of Etowah's elite class. Where proximity to copper protected the fibers from degeneration, archaeologists also found brightly colored cloth with ornate patterns. These were the remnants of the clothing of social elites. Numerous clay figurines and ten Mississippian stone statues have been found through the years in the vicinity of Etowah. Many are paired statues, which portray a man sitting cross-legged and a woman kneeling. The female figures wear wrap-around skirts and males are usually portrayed without visible clothing, although both usually have elaborate hairstyles. The pair are thought to represent lineage ancestors. Individual statues of young women also show them kneeling, but with additional characteristics such as visible sex organs, which are not visible on the paired statues. This female figure is thought to represent a fertility or Earth Mother goddess. The birdman, hand in eye, solar cross, and other symbols associated with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex appear in many artifacts found at Etowah.

Warren K. Moorehead's excavations into Mound C at the site revealed a rich array of Mississippian culture burial goods. These artifacts, along with the collections from Cahokia, Moundville Site, Lake Jackson Mounds, and Spiro Mounds, would comprise the majority of the materials which archaeologists used to define the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC). The professional excavation of this enormous burial mound contributed major research impetus to the study of Mississippian artifacts and peoples. It greatly increased the understanding of pre-Contact Native American artwork.

Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park (8LE1) is one of the most important archaeological sites in Florida, the capital of chiefdom and ceremonial center of the Fort Walton Culture inhabited from 1050-1500. The complex originally included seven earthwork mounds, a public plaza and numerous individual village residences.

One of several major mound sites in the Florida Panhandle, the park is located in northern Tallahassee, on the south shore of Lake Jackson. The complex has been managed as a Florida State Park since 1966. On May 6, 1971, the site was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as reference number 71000241.

The site was built and occupied between 1000 and 1500 by people of the Fort Walton culture, the southernmost expression of the Mississippian culture. The scale of the site and the number and size of the mounds indicate that this was the site of a regional chiefdom, and was thus a political and religious center.

After the abandonment of the Lake Jackson site the chiefdom seat was moved to Anhaica (rediscovered in 1987 by B. Calvin Jones and located within DeSoto Site Historic State Park), where in 1539 it was visited by the Hernando de Soto entrada, who knew the residents as the historic Muskogean-speaking Apalachee people. Other related Fort Walton sites are located at Velda Mound (also a park), Cayson Mound and Village Site and Yon Mound and Village Site.

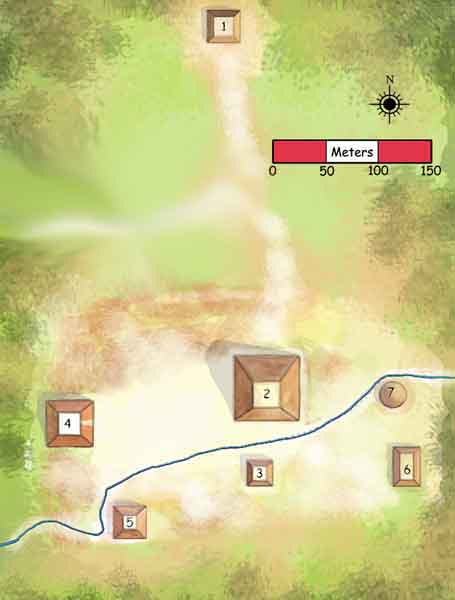

When the site was abandoned it was a large complex (19.0 hectares (0.073 sq mi)) that included seven platform mounds, six arranged near a plaza and a seventh (Mound 1) located 250 metres (820 ft) to the north. The mounds were the result of skilled planning, knowledge of soils and organization of numerous laborers over the period of many years. The ceremonial plaza was a large flat area, constructed and leveled for this purpose, where ritual games and gatherings took place.

Diagram showing the various components of mound construction

The area around the mounds and plaza had several areas of heavy village habitation with individual residences, where artisans and workers lived. There were also communal agricultural fields in the surrounding countryside, where the people cultivated maize in the rich local soil, the major reason such a dense population and large site were possible. Only a few of the mounds in the park have been systematically excavated by archaeologists.

The site itself is oriented on an east-west axis, oriented perpendicular to the north-south axis of the Meginnis Arm, a nearby extension of Lake Jackson. All of the mounds are laid out to reflect this alignment, although it is unclear if this is symbolic or merely the result of the lake arms orientation.

The layout and arrangement of the mounds in the central area of the site suggests that there may have been two large plaza areas. Mounds 2, 3, 4, and 5 form a large rectangular shape that was mostly free of debris. Mounds 2, 3, 6, and 7 also form a rectangular shape that suggests it too was a plaza. Both plazas would have had Butler's Mill Creek (a small stream that once bisected these areas, but whose course was altered in historic times) running through it. Excavations have shown that a clean area between Mounds 2 and 4 was a plaza, but not enough work has been done at the rest of the site to confirm the larger dimension suggested by the first arrangement or the existence of a plaza at the second arrangement at all.

A view of the site from the top of Mound B looking toward Mound A and the plaza.

Moundville Archaeological Site also known as the Moundville Archaeological Park, is a Mississippian culture site on the Black Warrior River in Hale County, near the town of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Extensive archaeological investigation has shown that the site was the political and ceremonial center of a regionally organized Mississippian culture chiefdom polity between the 11th and 16th centuries.

The archaeological park portion of the site is administered by the University of Alabama Museums and encompasses 185 acres (75 ha), consisting of 29 platform mounds around a rectangular plaza. The site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Moundville is the second-largest site of the classic Middle Mississippian era, after Cahokia in Illinois. The culture was expressed in villages and chiefdoms throughout the central Mississippi River Valley, the lower Ohio River Valley, and most of the Mid-South area, including Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi as the core of the classic Mississippian culture area. The park contains a museum and an archaeological laboratory.

The site was occupied by Native Americans of the Mississippian culture from around 1000 AD to 1450 AD. Around 1150 AD it began its rise from a local to a regional center. At its height, the community took the form of a roughly 300-acre (121 ha) residential and political area protected on three sides by a bastioned wooden palisade wall, with the remaining side protected by the river bluff.

A view across the plaza from mound J to mound B, with mound A in the center.

The largest platform mounds are located on the northern edge of the plaza and become increasingly smaller going either clockwise or counter clockwise around the plaza to the south. Scholars theorize that the highest-ranking clans occupied the large northern mounds, with the smaller mounds' supporting buildings used for residences, mortuary, and other purposes.

Of the two largest mounds in the group, Mound A occupies a central position in the great plaza, and Mound B lies just to the north, a steep, 58 feet (18 m) tall pyramidal mound with two access ramps; it rises to a height of 58 feet. Along with both mounds, archaeologists have also found evidence of borrow pits, other public buildings, and a dozen small houses constructed of pole and thatch.

Archaeologists have interpreted this community plan as a sociogram, an architectural depiction of a social order based on ranked clans. According to this model, the Moundville community was segmented into a variety of different clan precincts, the ranked position of which was represented in the size and arrangement of paired earthen mounds around the central plaza.

By 1300, the site was being used more as a religious and political center than as a residential town. This signaled the beginning of a decline, and by 1500 most of the area was abandoned.

Crooks Mound in Louisiana is a large, conical, burial mound that was part of at least six episodes of burials. It is located in La Salle Parish in south central Louisiana. It is a large, conical, burial mound that was part of at least six episodes of burials. It measured about 16 ft high (4.9 m) and 85 ft wide (26 m). It contained roughly 1,150 remains that were placed however they were able to be fit into the structure of the mound. Sometimes body parts were removed in order to achieve that goal. Archaeologists think it was a holding house for the area that was emptied periodically in order to achieve this type of setup

Most of the time, the people were just placed into the mound, but a few of the burials were in log-lined tombs or rarely stone lined tombs. Only a few out of each burial were interred with copper tools as grave goods. This suggests that the area was mainly for common people to be buried in. The site is on private land, usually with no public access but you are able to view it from the roadway.

There were two separate mounds that make up the site. In 1938-1939 the site was completely excavated under the direction of James A. Ford. The mounds were 1,200 feet (370 m) southeast of French Fork Bayou and 450 feet (140 m) southwest of Cypress Bayou. Mound A was a conical mound that stood 21 feet high and 84 feet in diameter.

Mound B was 2 feet (0.61 m) high and 50 feet (15 m) in diameter and located 110 feet (34 m) southwest of Mound A. Excavations revealed that Mound A had been built in three stages; Mound B was a single-stage structure. The mounds held 1,175 burials: 1,159 from Mound A, and 13 from Mound B (3 unknown). Pottery accompanied some burials; the weight of mound fill apparently crushed the vessels. The mounds were used for burials around 100 BCE to 400 CE. No evidence for domestic structures exists on or near the mounds, leading archaeologists to believe they were strictly for mortuary purposes.

Miamisburg is the location of a prehistoric Indian burial mound (tumulus), believed to have been built by the Adena Culture, about 1000 to 200 BCE. Once serving as an ancient burial site, the mound has become perhaps the most recognizable historic landmark in Miamisburg. It is the largest conical burial mound in Ohio, originally nearly 70 feet tall (the height of a seven-story building) and 877 feet in circumference; it remains virtually intact from its construction perhaps 2500 years ago. Located in a city park at 900 Mound Avenue, it has been designated an Ohio historical site. It is a popular attraction and picnic destination for area families. Visitors can climb to the top of the Mound, via the 116 concrete steps built into its side. Read more ...

Crop Circle Miamisburg Mound Rense.com - September 3, 2004

The formation was reported September 1, 2004 just to the southeast of the Miamisburg Mound in Miamisburg, Ohio. The Miamisburg Mound is the largest conical burial mound in the Eastern USA constructed approximately 2,000 years ago and is about seven stories high.

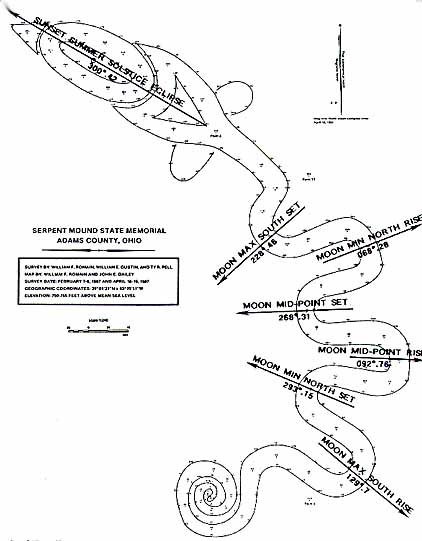

The Great Serpent Mound is the largest effigy mound in the world. While there are several burial mounds around the Serpent mound site, the Serpent itself does not contain any human remains and wasn't constructed for burial purposes. It is located in Adams County, Ohio.

1,330 feet in length along its coils and averaging three feet in height. One of many sacred places associated with ancient wisdom identified by the serpent symbol. Nearly a quarter of a mile long, Serpent Mound apparently represents an uncoiling serpent.

The head of the serpent is aligned to the summer solstice sunset and the coils also may point to the winter solstice sunrise and the equinox sunrise. Today, visitors may walk along a footpath surrounding the serpent and experience the mystery and power of this monumental effigy. A public park for more than a century, Serpent Mound attracts visitors from all over the world. The museum contains exhibits on the effigy mound and the geology of the surrounding area.

Serpent Mound lies on a plateau overlooking the valley of Brush Creek. It is located on a plateau with a unique cryptoexplosion structure that contains faulted and folded bedrock, which is usually either produced by a meteorite or volcanic explosion.

This cryptoexplosion structure has caused Serpent Mound to become misshapen over the years. This is one of the only places in North America where such an occurrence is seen. Though the meaning is grounds for debate, the mound's placement on such an area is almost undoubtedly not by coincidence. Glotzhober & Lepper summarize the dispute in their work.

Put it another way. The experts can not agree whether the immediate geological area of Serpent Mound was created from within the earth or from without. Geologists from the Ohio Division of Natural Resources Division of Geological Survey and from the University of Glasgow (Scotland) concluded in 2003 that a meteorite strike was responsible for the formation after studying core samples collected at the site in the 1970s. Further analyses of the rock core samples recovered at the site indicated the meteorite impact occurred during the Permian Period, about 248 to 286 million years ago.

Nearby conical mounds contained burials and implements characteristic of the prehistoric Adena people (800 BC-AD 100). Many questions surround the meaning of Serpent Mound, but there is little doubt it symbolized some religious or mythical principle for its builders. The museum contains exhibits on the mound and the geology of the surrounding area.

The date and creators of the Serpent mound is still debated among archaeologists. Several legitimate attributions have been made concerning both of these questionable factors: The Adena culture and the Fort Ancient culture. Both of these sub-cultures belonged to the broader Hopewell culture, a term used to encompass all of the pre-Columbian Native American groups that resided in Southern Ohio. All of these civilizations had similar characteristics, including burial mounds and effigy mounds, such as the Serpent Mound.

Historically, the mound has been attributed to the Adena Indians (800 BC-AD 100). Many nearby mounds can be assuredly contributed to the Adena culture. The Adena are also renowned for their elaborate earthworks.

However, recent carbon dating studies place the serpent mound outside of the span of the Adenas. There are also no cultural artifacts present within the mound, a trait of most other Adena mounds. This could possibly be because the mound is not of Adena origin, or that it held a special significance above other burial mounds.

A few pieces of wood charcoal were found in the undisturbed portion of the serpent mound. When carbon dating experiments were undertaken on these artifacts, the first two yielded a date of ca. 1070 AD, with the third piece dating to the Late Archaic period.

The first two dates place the Serpent Mound within the realm of the Fort Ancient Indians, a Mississippian culture, but the third back to very early Adena or before. The Fort Ancient Indians could very well have been the erectors of the Serpent Mound. A significant symbol in the Mississippian culture is the rattlesnake, which would explain the design of the mound.

However, this mound, if built by the Fort Ancient Indians, is uncharacteristic for that group. They also buried many artifacts in their mounds, something of which the Serpent Mound is devoid. Also, the Fort Ancient Indians did not usually bury their dead in the manner which the remains have been found at the effigy.

Astronomy - The head of the serpent is aligned to the summer solstice sunset and the snake's coils align with the winter solstice sunrise and the equinox sunrise. It is thought that perhaps the mound was created as a response to astrological occurrences.

The carbon dating attribution of 1070 coincides with two significant astronomic events - The appearance of Halley's Comet in 1066 and the light from the supernova that created Crab Nebula in 1054. This light was visible for two weeks after it first reached earth, even during the day. There is speculation that the serpent mound was to emulate a comet, slithering across the night sky like a snake.

The Serpent Mound was first discovered by two Chillicothe men, Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin H. Davis. During a routine surveying expedition, Squier and Davis discovered the unusual mound in 1846. They took particularly careful note of the area. When they published their book, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, in 1848, they included a detailed description and a map of the serpent mound.

One man who it particularly intrigued was Frederick Ward Putnam of the Peabody Museum of Harvard University. Putnam was fascinated with the mounds, specifically the Serpent Mound. When he visited the mounds in 1885, Putnam found that they were gradually being destroyed by plowing. Putnam raised funds, and in 1886 purchased the land in the name of the university to be used as a public park.

Excavation of the Serpent Mound - After raising sufficient funds, Putnam returned to the site in 1886. He worked for three years excavating the contents and burial sequences of both the Serpent Mound and two nearby conical mounds. After his work was completed and his findings documented, Putnam worked on restoring the mounds to their original state. In 1900, Harvard University turned over the Serpent Mound to the Ohio Historical Society to operate as a public park.

The Serpent Mound is one of those rare loci of the planet's topography where the consummate joining of terrestrial magnetism with astronomical alignments serves to astonish one at the accomplishments of our ancestry's knowledge of Earth and Heaven.

Unless you are an experienced geologist, the unique features of the topography of the lands surrounding the Serpent Mound are not obvious. The land rises and falls, sometime in gentle slopes but often sharply with steep contours, like the outcrop of stone and earth the serpent sits upon.

Through the land, flows many streams, some maintaining their flow throughout the summer. From atop the tower constructed to give tourists an elevated view of the mound, you also see a land covered with mixed hardwoods and the occasional evergreen. The view appears little different from the rest of southern Ohio, but within recent years the land here has been found to be unique. I believe the Adena peoples knew it over two thousand years ago when they sculpted this serpent out of stone, clay, and dirt.

In 1933 W.H. Bucher published an account of this area calling it a cryptovolcanic structure. Bucher was German, and his article was published in a German publication. Perhaps it takes an outsider to see the inner qualities of a place. Bucher saw similarities in the land forms at the Serpent Mound to barely recognizable volcanic upheavals in Germany. But like so many who speculate about the mounds, he saw what he wished to see.

No volcanic materials have been found here; however, he helped people see what is hardest to see: the familiar as strange. In 1947 R.D. Dietz in Science magazine suggested that a better name to describe the land features was "cryptoexplosion" - the folded and faulted beds of landforms from different geologic eras exposed from the impact of meteors.

The central area is characterized by uplifted and faulted Silurian and Ordovician rocks that have been folded sharply into seven radiating anticlines. The forces that produced this structure caused the central area to be uplifted a minimum of 950 feet. Shatter cones - shock - produced structures - are found in moderate amounts in the central area.

This description is from a map showing a nearly circular area representing the disturbed landscape; looking closely you can see the serpent mound sitting on the circumference of the circle. There is a great appeal to Dietz's theory even if the geology does not completely support it; there is no meteoric metal here.

But there are serious suggestions that the serpent is intimately connected with the heavens. Several writers have suggested that the serpent is a model of the constellation we call the Little Dipper, its tail coiled about the north star. It is tempting to believe that the Indians knew of the meteor's explosion into the earth, and they built the mound to honor that event.

Bucher's theory and the variation of it is supported more by the evidence of the rocks and the symbolism of the mound. The explosion came from within the earth from the incredible pressure of accumulated but repressed energies, trapped, blocked, but finally exploding upward as gas forcing its way to be released through the body of the earth toward the sky above.

Old maps of the area show Mounds at these places where the waterways meet, which some people consider gateways - the ways of passage, movement of consciousness between realities. This signifies the inner energies of the earth all embody.

This powerful energy rising from the depths of the earth-body is the energy of transformation, the energy that destroys blockages and barriers to the higher states of consciousness. It is the energy charted by shamans of every primary culture, the energy inherent in every human body.

In Ohio we also find the Decalogue Stone - Battle Creek Stone.

Wonders of geometric procession, the earthworks and mounds of the lower Mississippi were centers of life long before the Europeans arrived in America, as was the river itself. The alluvial soil of its banks yielded a bounty of beans, squash, and corn to foster burgeoning communities. Over the Mississippi's waters, from near and far, came prized pearls, copper, and mica.

Along Mississippi's scenic Natchez Trace Parkway sits an immense flat-topped platform 35 feet high, spanning eight acres.

Emerald Mound the second largest ceremonial earthwork in the United States, was built over two centuries before Columbus waded ashore in the Caribbean. The Mississippians erected hundreds - maybe thousands - of earthworks across the southeast while Europe was living through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

As the Mississippians flourished, the mounds evolved into urban centers with the common city problems of overcrowding and waste disposal. Sometimes one large flat-topped mound dominated a village or ceremonial center. More often, as at Emerald, several mounds surrounded a plaza, with the village at its edges. Structures atop the plaza - temples or official residences - sat on large four-sided flat-topped mounds. A palisade of saplings surrounded the entire complex.

Periodically, the Mississippians would raze one of the wood-and-mud structures, bury the remains of a deceased leader in a fresh layer of earth, and erect a new building on top. Commonly, the well-to-do were laid to rest in specially built burial mounds, conical or round.

Crews labored periodically over generations, sometimes a century or more, before an earthwork reached its final dimensions. A mound might begin as a slight rise with an important building on it. After a time, perhaps it might burn accidentally or people would burn it down as part of a cleansing ceremony. The crews brought basket after basket of dirt to cover the old and lay a new foundation, and another building went up.

Many workers, hauling 60 pounds of soil apiece, labored to complete each stage. Some archeologists say that the culture's survival depended on a steady flow of immigrants to compensate for the high death rates. When the flow ceased, they argue, the cities collapsed.

Today, most of the moundbuilders' legacy is gone. Many of their earthworks have been plowed, pilfered, eroded, and built over. Yet evidence of the culture remains. This website is part of an effort to preserve the legacy that survives along the banks of the lower Mississippi.

The Mississippian Native American Platform Mound

Spiro Mounds is an important pre-Columbian Caddoan Mississippian culture archaeological site located in present-day eastern Oklahoma in the United States. The site is located seven miles north of Spiro, and is the only prehistoric Native American archaeological site in Oklahoma open to the public. The prehistoric Spiro people thrived and created a strong religious center and political system.

The site was eventually abandoned after several hundred years of occupation, although it is still unclear why. The Great Mortuary at the site was looted in the 1930s. Many of the looted artifacts were eventually tracked down, although many others were destroyed by the looters, who used dynamite on the mound to gain access to its contents. The mounds site has been significant to North American archaeology since the 1930s, especially in the defining of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the site is under the protection of the Oklahoma Historical Society and open to the public.

Spiro is the western-most known outpost of the Mississippian culture, which arose and spread along the lower Mississippi River and its tributaries between the 9th century and 16th century CE. Cahokia, a major chiefdom that built a six-mile-square city, arose east of St. Louis in present-day Illinois. Mississippian culture extended along the Ohio River and into the southeast, and the trading network ranged from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast and into the southeastern mountains.

The Spiro area includes twelve mounds and 150 acres of land. As in other Mississippian-culture towns, the people built a number of large, complex earthworks. These included earthen mounds surrounding a large, planned and leveled central plaza, where important religious rituals, the politically and culturally significant game of chunkey, and other important community activities were carried out. The population lived in a village that bordered the plaza. In addition, archaeologists have found more than twenty other related village sites within five miles of the main town. Other village sites linked to Spiro through culture and trade have been found up to a 100 miles (160 km) away.

Spiro has been the site of human activity for at least 8000 years, but was a major settlement from 800 to 1450 CE. The cultivation of maize allowed accumulation of crop surpluses and the gathering of more dense populations. It was the headquarters town of a regional chiefdom, whose powerful leaders directed the building of eleven platform mounds and one burial mound in an 80-acre (0.32 km2) area on the south bank of the Arkansas River.

The heart of the site is a group of nine mounds surrounding an oval plaza. These mounds elevated the homes of important leaders or formed the foundations for religious structures that focused the attention of the community. Brown Mound, the largest platform mound, is located on the eastern side of the plaza. It had an earthen ramp that gave access to the summit from the north side. Here, atop Brown Mound and the other mounds, the town's inhabitants carried out complex rituals, centered especially on the deaths and burials of Spiro's powerful rulers.

Archaeologists have shown that Spiro had a large resident population until about 1250 CE. After that, most of the population moved to other towns nearby. Spiro continued to be used as a regional ceremonial center and burial ground until about 1450 CE. Its ceremonial and mortuary functions continued and seem to have grown after the main population moved away.

Craig Mound - also called "The Spiro Mound" - is the second-largest mound on the site and the only burial mound. It is located about 1,500 feet (460 m) southeast of the plaza. A cavity created within the mound, about 10 feet (3.0 m) high and 15 feet (4.6 m) wide, allowed for almost perfect preservation of fragile artifacts made of wood, conch shell, and copper. The conditions in this hollow space were so favorable that objects made of perishable materials such as basketry, woven fabric of vegetal and animal fibers, lace, fur, and feathers were preserved inside it. Such objects have traditionally been created by women in historic tribes. Also found inside were several examples of Mississippian stone statuary made from Missouri flint clay and Mill Creek chert bifaces, all thought to have originally come from the Cahokia site in Illinois.

The "Great Mortuary," as archaeologists called this hollow chamber, appears to have begun as a burial structure for Spiro's rulers. It was created as a circle of sacred cedar posts sunk in the ground and angled together at the top like a tipi. The cone-shaped chamber was covered with layers of earth to create the mound, and it never collapsed. Some scholars believe that minerals percolating through the mound hardened the chamber's log walls, making them resistant to decay and shielding the perishable artifacts inside from direct contact with the earth. No other Mississippian mound has been found with such a hollow space inside it and with such spectacular preservation of artifacts. Craig Mound has been called "an American King Tut's Tomb."

Artifact hunters looted Craig Mound between 1933 and 1935, tunneling into the mound and breaking through the Great Mortuary's log wall. They found many human burials, together with their associated grave goods. The looters discarded the human remains and the fragile artifacts, which were made of copper, shell, stone, basketry and textile, traditionally made by women of the culture. Most of these rare and historically priceless objects disintegrated before scholars could reach the site, although some were sold to collectors.The looters dynamited the burial chamber when they were finished and quickly sold the commercially valuable artifacts, made of stone, pottery, and conch shell, to collectors in the United States and overseas. Most of these valuable objects are probably lost, but some have been recovered and documented by scholars.