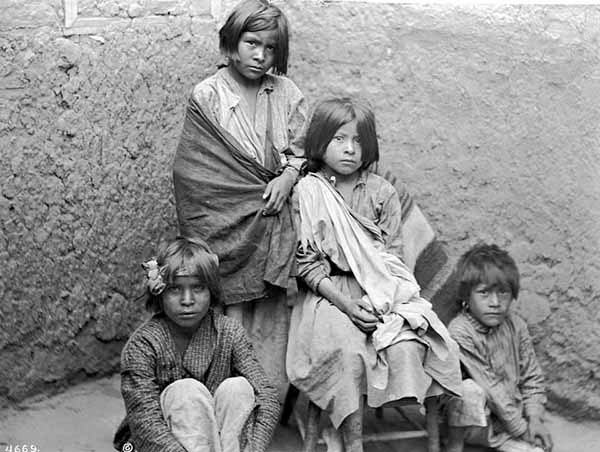

The Zuni or Ashiwi are Native American Pueblo peoples native to the Zuni River valley. The current day Zuni are a Federally recognized tribe and most live in the Pueblo of Zuni on the Zuni River, a tributary of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico, United States. The Pueblo of Zuni is 55 km (34 mi) south of Gallup, New Mexico.The Zuni tribe lived in multi level adobe houses. In addition to the reservation, the tribe owns trust lands in Catron County, New Mexico, and Apache County, Arizona. The Zuni call their homeland Halona IdiwanÕa or Middle Place.

Archaeology suggests that the Zuni have been farmers in their present location for 3,000 to 4,000 years. It is now thought that the Zuni people have inhabited the Zuni River valley since the last millennium B.C., at which time they began using irrigation techniques which allowed for farming maize on at least household-sized plots.

More recently, Zuni culture may have been related to both the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo peoples cultures, who lived in the deserts of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and southern Colorado for over two millennia. The "village of the great kiva" near the contemporary Zuni Pueblo was built in the 11th century AD. The Zuni region, however, was probably only sparsely populated by small agricultural settlements until the 12th century when the population and the size of the settlements began to increase. In the 14th century, the Zuni inhabited a dozen pueblos between 180 and 1,400 rooms in size. All of these pueblos, except Zuni, were abandoned by 1400, and over the next 200 years, nine large new pueblos were constructed. These were the "seven cities of Cibola" sought by early Spanish explorers. By 1650, there were only six Zuni villages.

In 1539, Moorish slave Estevanico led an advance party of Fray Marcos de Niza's Spanish expedition. The Zuni reportedly killed Estevanico as a spy. This was Spain's first contact with any of the Pueblo peoples.[9] Francisco V‡squez de Coronado traveled through Zuni Pueblo. The Spaniards built a mission at Hawikuh in 1629. The Zunis tried to expel the missionaries in 1632, but the Spanish built another mission in Halona in 1643.

Before the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the Zuni lived in six different villages. After the revolt, until 1692, they took refuge in a defensible position atop Dowa Yalanne, a steep mesa 5 km (3.1 miles) southeast of the present Pueblo of Zuni; Dowa means "corn", and yalanne means "mountain". After the establishment of peace and the return of the Spanish, the Zuni relocated to their present location, returning to the mesa top only briefly in 1703.

The Zunis were self-sufficient during the mid-19th century, but faced raiding by the Apaches, Navajos, and Plains Indians. Their reservation was officially recognized by the United States federal government in 1877.

Frank Hamilton Cushing, an anthropologist associated with the Smithsonian Institution, lived with the Zuni from 1879 to 1884. He was one of the first non-native participant-observers and ethnologists at Zuni.

In 1979, however, it was reported that some members of the Pueblo consider he had wrongfully documented the Zuni way of life, exploiting them by photographing and revealing sacred traditions and ceremonies.

A controversy during the early 2000s was associated with Zuni opposition to the development of a coal mine near the Zuni Salt Lake, a site considered sacred by the Zuni and under Zuni control. The mine would have extracted water from the aquifer below the lake and would also have involved construction between the lake and the Zuni. The plan was abandoned in 2003 after several lawsuits.

The Zuni people are, in a way, a mysterious tribe. Their culture is very reclusive and isolated much as is their city and their language. They are a very interesting people who are well known for their beautiful artwork, sculpture and dishware. The Zuni are one of the few fortunate tribes who have managed to keep their ways of life the same throughout the years despite the westward push of the European immigrant settlers, the Mexican-American war, and the rough treatment they endured during all of the conflicts that they dealt with.

The Zuni traditionally speak the Zuni language, a language isolate that has no known relationship to any other Native American language. Linguists believe that the Zuni have maintained the integrity of their language for at least 7,000 years. The Zuni do, however, share a number of words from Keresan, Hopi, and Pima pertaining to religion and religious observances.[14] The Zuni continue to practice their traditional religion with its regular ceremonies and dances, and an independent and unique belief system.

The Zuni were and are a traditional people who live by irrigated agriculture and raising livestock. Gradually the Zuni farmed less and turned to sheep and cattle herding as a means of economic development. Their success as a desert agri-economy is due to careful management and conservation of resources, as well as a complex system of community support. Many contemporary Zuni also rely on the sale of traditional arts and crafts. Some Zuni still live in the old-style Pueblos, while others live in modern houses. Their location is relatively isolated, but they welcome respectful tourists.

The Zuni Tribal Fair and rodeo is held the third weekend in August. The Zuni also participate in the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial, usually held in early or mid-August. The A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center is a tribal museum that showcases Zuni history, culture, and arts.

Men wear loin cloths, fringed white cotton sashes, deerskin moccasins, and short leggings. Women wear Pueblo dress, fastened over right shoulder, footless stockings, and bare feet.

While many anthropologists believe that the Zuni are related to the other pueblo tribes that are scattered throughout the Southwest, they are unique in that their language, to this day, is only spoken by them and bares no resemblance to the languages of any of the other surrounding tribes. Their language is often called Zunian.

Zuni life, much like it was in the past, is still deeply religious and very different from that of other tribes. Their are an agricultural society.

The civil government is of a form generally imposed upon the Pueblos by Spanish influence. The governor,'Tapupu', and the lieutenant-governor, 'Tsipalaa-shiwanni', are appointed annually by a priestly group, consisting of the six so called rain-priests ('Ashiwanni") associated with the world-regions, the two war-chiefs or Bow Chiefs, and Shiwan-akya ("chief old-woman).

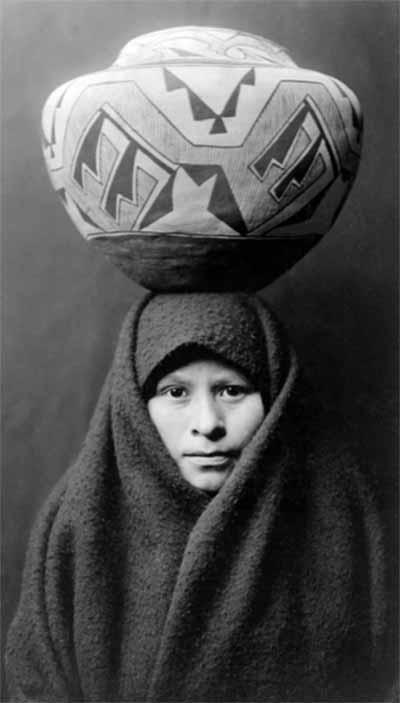

Traditionally, Zuni women made pottery for food and water storage. They used symbols of their clans for designs. Clay for the pottery is sourced locally. Prior to its extraction, the women give thanks to the Earth Mother (Awidelin Tsitda) according to ritual. The clay is ground, and then sifted and mixed with water.

After the clay is rolled into a coil and shaped into a vessel or other design, it will be scraped smooth with a scraper. A thin layer of finer clay, called slip, is applied to the surface for extra smoothness and color. The vessel is polished with a stone after it dries. It is painted with home-made organic dyes, using a traditional yucca brush. The intended function of the pottery dictates its shape and images painted on its surface. To fire the pottery, the Zuni used animal dung in traditional kilns.

Today Zuni potters might use electric kilns. While the firing of the pottery was usually a community enterprise, silence or communication in low voices was considered essential in order to maintain the original "voice" of the "being" of the clay, and the purpose of the end product. Sales of pottery and traditional arts provide a major source of income for many Zuni people today. An artisan may be the sole financial support for her immediate family as well as others. Many women make pottery or, less frequently, clothing or baskets

Contemporary Zuni Indians are the direct descendants of the prehistoric Pueblo people who settled the region sometime prior to A.D. 400. Mirroring the developments that took place throughout the region occupied by prehistoric Pueblo Peoples, the first settlements in the area were comprised of agriculturalists living in pit-houses of various types. Later above-ground masonry structures (pueblos) were comprised of small, dispersed room blocks associated with subterranean pit structures or kivas.

By A.D. 1000, the population in the Zuni area began to construct larger settlements oriented around Chacoan great houses with associated circular great kivas. Throughout this period, the occupation spans of most settlements were relatively brief, and many new villages were constructed over a wide area, perhaps in response to variability in climate and the gradually decreasing productivity of agricultural strategies.

Houses are built of fragments of stone, set sometimes without binding material and without breaking joints. The walls are plastered on both sides with clay and whitened on the inside with gypsum wash. The flat, slightly sloping roof of brush and earth is supported by heavy pine beams stripped of their bark but not dressed. The quarters of a family are an apartment in a terraced structure containing hundreds of rooms. Houses on the ground level were formerly entered through the roof by means of ladders. The upper levels are either reached by ladders or by stone stairs ascending from one roof to another.

A house, though built by the men, are the absolute property of the women, who may sell or trade them within the tribe without legal hindrance from husband or children.

Zuni mythology is the oral history, cosmology, and religion of the Zuni people. The Zuni are a Pueblo people located in New Mexico. Their religion is integrated into their daily lives and respects ancestors, nature, and animals Due to a history of religious persecution by non-native peoples, they are very private about their religious beliefs. Roman Catholicism has to some extent been integrated into traditional Zuni religion.

Cultural institutions that provide religious instruction and cultural stability include their priests, clans, kivas (kachina society), and healing societies. A ceremonial cycle brings the community together. While some ceremonies are open to non-Zuni peoples, others are private; for instance the Shalako ceremony and feast has been closed to outsiders since 1990.

The three most powerful supernatural beings are Earth Mother, Sun Father and Moonlight-Giving Mother. Sunlight is recognized as vital for life, and the word for "daylight" and "life" are the same word in the Zuni language. Sunrise is a special and very sacred time.

For the A:shiwi, there are six directions: North, South, East, West, Above and Below. Because of the extra two directions, there is also the "middle", which is the connecting point.

In addition to ceremonies honoring and thanking supernatural beings and natural forces for health and well-being, there are rituals to mark important times in each person's life including birth, coming of age, marriage and death.

The Zunis believe that, while all parts of the universe belong to a single system of interrelated life, degrees of relationship based on resemblance exist. The starting point in this system is humanity, which is the lowest because it is the least mysterious and the most dependent. The animals that most resemble humans are considered closest to them in the great web of interrelatedness. The animals, objects, or phenomena that least resemble them are believed to be the least related and, thus, the most mysterious and holy.

A dog, for example, would be viewed as less holy than a snake or other reptile, because dogs and humans live together and have a mutual understanding, whereas reptiles are alien to the human world. Since forces in nature such as wind, lightning, and rain-are very mysterious and powerful, they are believed to be closer to the deities than either humans or animals.

Zuni make fetishes and necklaces for the purpose of rituals and trade, and more recently for sale to collectors. The Zuni are known for their fine lapidary work. Zuni jewelers set hand-cut turquoise and other stones in silver. Today jewelry-making thrives as an art form among the Zuni. Many Zuni have become master stone-cutters. Techniques used include mosaic and channel inlay to create intricate designs and unique patterns.

Two specialities of Zuni jewelers are needlepoint and petit point. In making needlepoint, small, slightly oval-shaped stones with pointed ends are set in silver bezels, close to one another and side by side to create a pattern. The technique is normally used with turquoise, sometimes with coral and occasionally with other stones in creating necklaces, bracelets, earrings and rings. Petit point is made in the same fashion as needlepoint, except that one end of each stone is pointed, and the other end is rounded.

Zunis believe that animals, as well as inanimate objects and the forces of nature, have a spirit force, which can either help or hurt man. It is believed that the carved animal fetishes host that spiritual force and, if treated properly, will help their owners to overcome the problems facing them.

At the most fundamental level, a fetish is "an object, natural or manmade, in which a Spirit is thought to reside, and which can be used to affect either good or evil." All American Indian tribes of the Southwest make use of charms, talismans, and amulets, but the Zuni Indians of New Mexico are especially renowned for their animal carvings. When the owner holds the belief that a "spirit" resides in the carved object, it becomes a fetish.

The earliest fetishes were found objects rather than crafted figures. Stones in the shapes of animals were believed to be actual petrifaction's of animals that had once lived and to contain the spirits of the animals they physically resembled. These fetishes put one in touch with the innate wisdom and characteristic qualities derived from the Zunis' knowledge of the natural world plus their mythology of the animals they depicted.

Early missionaries in the Southwest mistakenly believed that the Zunis worshipped these little figures as idols, but this was not the case. The idol worshipper believes the object itself to be a deity, while the fetishist looks upon the object as a representation of a spirit or force that is evoked through the figure. The Zunis use the fetish as a messenger to assist them in their communications with the spirits and deities.

At its most rudimentary level, consultation with a fetish might be compared to the act of prayer, meditation, or contemplation-and it is an activity which is accessible to all persons, regardless of cultural origins. Just as our knowledge of any form or force, and our empathy with it, can be evoked through our words, so the same can be evoked-in a perhaps more complete form-through the fetish.

Holding fetishes in our hands or placing them before us as we pray or meditate, we bring ourselves more and more in line with their spirits. And it is through this alignment with Spirit that we experience the fetish's greatest power. Anthropologist Tom Bahti states that the fetish was intended to "assist man, that most vulnerable of all living creatures, in meeting the problems that face him during his life. Each fetish contains a living power which, if treated properly and with veneration, will give its help to its owner.

According to Zuni cosmology, everything in the universe-from natural forces, such as lightning, wind, or great droughts, to physical entities, such as rocks, animals, rivers, and human beings-has its own spirit. Each of these spirits has the power to observe, think, and respond to humankind. An inanimate object, such as a rock or a clump of dirt, is believed to possess a spirit similar to that of a hibernating bear or a seed that has not yet been planted. The power is simply dormant, for the moment. Moreover, all forces and life forms have their origin in, and are constantly part of, a larger force-comparable to the Tao- for which there is no name. Zuni religion teaches that we are all part of an endless sea of Spirit in which appear an infinite number of physical forms.

The fetish provides its owner with an icon or reference point for navigating in a spiritual world where there are few objective boundaries. In this respect, our conversations with the fetishÕs spirit remind us of our relationship with the organizing force of the universe, thus connecting us with a power that is infinitely greater than our own egos.

For the traditional Zuni, the fetish is just one aspect of a complex religion whose central goal is to achieve a balance with nature. Throughout the Zuni religion, there is great reverence for the unseen world-the mysterious forces created by A'wonawil'ona which continue to impact on all life. Zuni religious beliefs foster a constant awareness of how dependent we humans are on the natural order and on external spiritual forces which are mysterious to us.

While the Zuni emphasize our dependence on these external forces, they also believe that we can bring ourselves into a harmonious and nurturing relationship with the deifies that control the forces. The fetish is a spiritual tool that can be used to establish and maintain this relationship.

According to the Zuni way, all human ills are the result of being out of balance with the natural forces, usually due to failure to observe nature's laws because of either ignorance or selfishness. There are many instructive stories in the Zuni culture that tell of men and women who acted vainly, attempting to assume power as if they were separate from or superior to A'wonawil'ona. Those who did so were always punished in some way, their punishments ranging from lack of luck in the hunt to great droughts which caused many deaths among their people.

When people began crafting fetishes from stone, wood, and other materials, it was believed that these had less power than the found objects whose resemblance to animals had been created by the forces of nature. However, there were then, as now, fetish makers with special wisdom about the spiritual and healing attributes of the animals and natural forces. A fetish crafted by such a person may be imbued with great powers.

The body of the fetish may be shaped from bone, shell, clay, stone, or other material. Various adornments may be attached to the fetish, some to strengthen the spirit within and some as votive offerings, given in appreciation for the fetish's service to its owner. Most shell or turquoise beads tied to modern fetishes would be classified as votive offerings, while arrowheads, feathers, or bones are usually attached to strengthen the fetish's powers.

Occasionally, the fetish may be decorated with etched and/or painted lines. These might depict the feathers or pinions of a bird, or they might echo traditional designs used in ceremonial dress, masks, or other sacred objects. One of the most commonly seen decorations of this kind is the "heartline arrow," a single line that runs from the tip of the fetish's nose or mouth directly back, on each side, to the area of the heart. At the heart, there is found the pattern of an arrowhead. In addition to representing the breath or life force of the animal spirit, the heartline evokes the qualities of the snake and lightning. A fetish decorated in this way is considered very powerful.

Most fetishes are kept and used in sets, usually consisting of between three and seven figures with a clay fetish jar to house them. Fetish jars measure up to approximately fourteen inches in height and sixteen inches in diameter. The bottoms of the jars are lined with down and, in some cases, sprinkled with powdered turquoise or shell, in order to make the fetishes comfortable. Most jars have a hole in the side, between one and four inches in diameter. The mouths of the jars are covered, usually with hide from deer that have been killed ritually. The fetishes are placed facing outward within their jars.

The outer surfaces of fetish jars are typically quite plain, except that turquoise dust and fragments may have been pressed into the clay before firing. Some jars are decorated with feathers, etched symbols representing natural forces, or even other fetishes which presumably guard the jar's mouth or feeding hole.

The jars are washed frequently, usually as part of a ceremony prescribed for the use of the fetishes that reside there. Each fetish set has a particular purpose, ranging from healing the sick to initiating young people into a clan or religious order.

Each year, usually around the winter solstice, the Zunis observe We-ma-a-wa u-pu-k'ia, or "The Day of the Council of Fetishes." On this day, all the fetishes belonging to the tribe and its individual members are brought to an altar in the Zuni council chamber. Animals are arranged according to their type and color on slats placed on the floor. Bird fetishes are suspended in the air, usually by cotton strings.

The ceremonials last throughout most of the night, with each member approaching the altar, addressing the assembly of fetishes with long prayers, and then scattering prayer meal over the altar. Songs and chants are sung, with participants imitating the movements and cries of the animals represented. The Day of the Council of Fetishes ends with a great feast. Tiny portions of each food are ritually fed to the fetishes, after which the scraps of food are buried.

As in all rituals surrounding the fetishes, the ceremonies, songs, dances, and offerings are ultimately addressed to A'wonawil'ona, whose spirit or life force permeates the land, the sky, the fetishes, the animals they represent, all the natural forces, and humanity itself{ linking all of us as One.

Zuni fetishes offer us a highly intuitive and spiritual way of getting in touch with guiding principles that can serve us in modem life, whether we are faced with challenges in our jobs, our relationships, or our spiritual paths. A fetish evokes both conscious and unconscious knowledge associated with the animal it represents. Thus, the fetishes provide us a way of going inside to discover our own natural resources-resources of the spirit that we each bring into this life at birth.

Zuni fetishes are often suspended from heishi necklaces, a uniquely Native American jewelry tradition. Animal and bird carvings with holes drilled in them, suggesting they were meant to be used as beads or worn as pendants, have been recovered from pre-Columbian archeological sites.

Long prized as powerful religious icons, first by other Indian tribes, and now by non-Indians, Zuni fetishes have become one of the most popular items in Native American cultural art today. The number of artisans carving fetishes in Zuni, New Mexico has swelled from only 15-20 in the early 1980s to over 200 today.

Each artisan generally makes a limited number of fetishes, both in style and in total output, usually focusing on a single animal or a small group of related animals. The craft is sometimes practiced by a whole family, and some family names are well recognized and respected for the consistent quality and artistry of their work.

Although each animal has a different power, Zuni carvers maintain that their carvings are not endowed with the power of the animal, unless blessed by a medicine man for a specific purpose. This blessing endows the fetish with powers governing fecundity, success in hunting, diagnosis and healing of disease, luck in gambling, or luck in general.

The belief is, that if you own that animal, and you treat it with respect, the animal will share its power with you. The power held by the animal is derived from a spirit dwelling within the fetish. Double fetishes are sometimes kept by couples to strengthen the bond between them. A double fetish is created by carving two animals from the same piece of stone. Fetishes representing animals that develop a strong bond between male and female, such as the wolf or swan, are particularly appropriate for this purpose.

Traditionally, fetishes were highly private objects, rarely shown to outsiders. The proper care of a fetish included keeping it in a special fetish bowl designed for that purpose and making offerings of cornmeal, and sometimes bits of turquoise and coral, to nourish its spirit. Fastened to the backs of some tabletop fetishes, are medicine bundles, small beads and arrows tied together with leather - a collection of amulets to ensure good fortune.

The smallest of carvings are most treasured by the Zuni, because of the skill and patience required to carve them. The electric drill used by modern artists allows them to render realistic figures in a variety of materials. Elements used for carving vary, including; abalone, alabaster, amber, coral, dolomite, fluorite, spiny oyster, ironwood, jet, lapis, malachite, mother-of-pearl, Picasso marble, pipestone, sandstone, serpentine, fossilized ivory, travertine and turquoise.

Some of the more popular animals and their powers:

Bear = Health and Strength

Wolf, Mountain Lion, Badger = Hunters

Eagle = Oversight, Good Luck

Mole = Protects Underneath

Frog = Fertility, Rain

Ram = Prosperity

Buffalo = Abundance

Carvings of birds, coyotes, foxes, horses, parrots, pigs, sheep, squirrels and turtles are popular as well.

As either tabletop carvings, or jewelry pieces, fetishes are a popular and unique expression of Native American culture. Although the stones, and many of the shapes, used for jewelry and fetishes have profound symbolic significance for the cultures producing them, even to the uninitiated, the beauty of the Zuni fetish work is immediately evident. - Zuni Fetish Page

The Zuni gods are believed to reside in the lakes of Arizona and New Mexico. The chiefs and the shamans during religious festivals carry out two different types of ceremonies. Song and dance accompanies masked performances by the chiefs while the shamans pray to the gods for favors ranging from fertile soil to abundant amounts of rain. The shamans play an important role in the community as they are looked upon for guidance as well as knowledge and healing. There are different levels of expertise for all shamans with the goal ultimately being to reach the top level so they can assist in all aspects of Zuni life.

The principal Zuni Gods are believed to dwell in the depths of a lake in Arizona. Zuni ceremonies are of two kinds: those in which masked men impersonate the ancestral gods and those in which the shamanistic societies play the leading part.

Although it is not uncommon to find religion playing a significant part in an Indian society, the fact that women are played an important role is quite uncommon. Women are thought of as the life of the tribe. Men do all of the hunting, building and gathering of necessities, but when they are done, whatever they have caught, collected or built belongs to the women. The women are the ones who do all of the trading with different tribes and take care of financial issues and problems. This is quite a change from most modern societies.

There are twelve shamanistic societies. These not only treat sickness, but participate as societies and perform feats of legerdemain for the mystification of the people. each has several orders or degrees, and each order is the custodian of some secret of healing or magic.Members are initiated successively into these orders, until ultimately they are competent to assist in the activities of all.

According to Ruth Kirk, there are six categories of fetishes in the Zuni religion.

The first category includes masks, costumes, and other sacred objects used in Kachina ceremonies; like other fetishes, these objects are fed, cared for, and offered daily prayers between ceremonies.

The second type of fetish is the mili, a personal fetish which consists of a perfect ear of corn (one that ends in five symmetrical rows), usually with a variety of feathers attached. Presented to a young man at the time he is initiated into a religious society, this fetish symbolizes the initiate's soul, as well as the life-giving power of the Creator.

Kirk's third group of fetishes, prayer sticks, are more properly classified as amulets because they do not have spirits residing within them.

The fourth category of fetishes, called "concretion fetishes," are naturally shaped rocks which are thought to be petrified organs of the gods that once walked on Earth; they are used for making contact with the spirits of those deities.

A fifth group of fetishes are the effowe, fetishes used in rainmaking ceremonies. An ettone (singular of effowe) consists of several short reeds wrapped in cotton string to form a compact, round bundle.

The Zuni year begins with the winter solstice, at which time occurs the ceremony called Yatakya-ittiwanna-quin-techikya ("sun middle-at place arrives"), or Tetsina-wittiwa ("winter middle").

The movements of the sun are observed daily by the Peqinne, chief of the zenith. In the six winter months, December to May, he goes at sunrise to a petrified stump just east of the village, and with offerings of sacred meal he prays to the rising sun and notes its position with reference to certain permanent natural marks on the horizon.

But in the six summer months he goes to the ruin of Matsaki two miles east of Zuni and prays to the setting sun while standing within a semicircular stone shrine and making note of the position of the sun on Yalanne-hlanna ("mountain big"), a high mesa northwest of Zuni.

When in November the rising sun coincides with a certain mark on Tawa-yalanne, Corn mountain, he so informs the Apihlan-shiwanni ("bow chiefs"), the war-chiefs, who in turn bear the news to the other five Ashiwanni, and these high priests assemble at once in the house of the Kyaqimassi, Shiwanni of the north.

Beginning on the next morning Peqinne at intervals of four days plant feathered prayer sticks (always four in number) alternately at a shrine on Corn mountain for Sun and Moon, and in the field for his deceased sun priests. This planting of prayer sticks covers twenty-one days, and during the period, as well as the four days preceding and four days following it, he practices continence. On the twenty-second morning he goes to the housetop and announces that on the tenth day thereafter the sun will arrive at Ittiwanna-qin ("middle at place"), a certain point on Corn mountain, and they will then celebrate his arrival and his four days' sojourn there before turning back to the north.

At night the images of the war gods are brought solemnly into the kiva, the six Ashiwanni and the Bow fraternity being the principal ones present, the latter having left the meeting of the various shamanistic societies to which they belong. After a night of prayers and offerings, the images are taken back to the houses where they were prepared, and after the morning meal the elder Bow Chief with an assistant carries the image of the elder god and deposits it at the war god's shrine on Uhana-yalanne, southwest of Zuni; and the younger Bow Chief carries the other image to the shrine on Corn mountain.

On the day named as the solstice each household as a unit goes into the fields to plant prayer sticks. Each member of the family, regardless of age, sex or connection with fraternity or priesthood, places one prayer stick or more (usually several) in a small hole dug out by the head of the household. The prayer sticks are intended for various deities and for deceased ancestors.

In a version of the Zuni creation story told to anthropologist Ruth Benedict, people initially dwelt crowded tightly together in total darkness in a place deep in the earth known as the fourth world. The daylight world then had hills and streams but no people to live there or to present prayer sticks to Awonawilona, the Sun and creator.

Awonawilona took pity on the people and his two sons were stirred to lead them to the daylight world. The sons, who have human features, located the opening to the fourth world in the southwest, but they were forced to pass through the progressively dimming first, second and third worlds before reaching the overcrowded and blackened fourth world. The people, blinded by the darkness, identified the two brothers as strangers by touch and called them their bow priests. The people expressed their eagerness to leave to the bow priests, and the priests of the north, west, south and east who were also consulted agreed.

To prepare for the journey, four seeds were planted by Awonawilona's sons, and four trees sprang from them: a pine, a spruce, a silver spruce and an aspen. The trees quickly grew to full size, and the bow priests broke branches from them and passed them to the people. Then the bow priests made a prayer stick from a branch of each tree. They plunged the first, the prayer stick made of pine, into the ground and lightning sounded as it quickly grew all the way to the third world. The people were told that the time had come and to gather all their belongings, and they climbed up it to a somewhat lighter world but were still blinded. They asked if this is where they were to live and the bow priests said, "Not yet".

After staying four days, they traveled to the second world in similar fashion: the spruce prayer stick was planted in the earth and when it grew tall enough the people climbed it to the next world above them. And again, after four days they climbed the length of silver spruce prayer stick to the first world, but here they could see themselves for the first time because the sky glowed from a dawn-like red light. They saw they were each covered with filth and a green slime. Their hands and feet were webbed and they had horns and tails, but no mouths or anuses. But like each previous emergence, they were told this was not to be their final home.

On their fourth day in the first world, the bow priests planted the last prayer stick, the one made of aspen. Thunder again sounded, the prayer stick stretched through the hole to the daylight world, and the people climbed one last time. When they all had emerged, the bow priests pointed out the Sun, Awonawilona, and urged the people to look upon him despite his brightness. Unaccustomed to the intense light, the people cried and sunflowers sprang from the earth where their tears fell. After four days, the people traveled on, and the bow priests decided they needed to learn to eat so they planted corn fetishes in the fields and when these had multiplied and grown, harvested it and gave the harvest to the men to bring home to their wives.

The bow priests were saddened to see the people were smelling the corn but were unable to eat it because they had no mouths. So when they were asleep, the bow priests sharpened a knife with a red whetstone and cut mouths in the people's faces. The next morning they were able to eat, but by evening they were uncomfortable because they could not defecate. That night when they were asleep the bow priests sharpened their knife on a soot whetstone and cut them all anuses.

The next day the people felt better and tried new ways to eat their corn, grinding it, pounding, and molding it into porridge and corncakes. But they were unable to clean the corn from their webbed hands, so that evening as they slept the bow priests cut fingers and toes into their hands and feet. The people were pleased when they realized their hands and feet worked better, and the bow priests decided to make one last change. That night as they slept, the bow priests took a small knife and removed the people's horns and tails. When the people awoke, they were afraid of the change at first, but they lost their fear when sun came out and grew pleased that the bow priests were finally finished.

How the Zunis wished for new music and new dances for their people when they participated in ceremonials!

Their Chief and his counsellors decided to ask their Old Grandfathers for help. They journeyed to the Elder Priests of the Bow and asked, "Grandfathers, we are tired of the same old music and the old dances. Can you please show us how to make new music and new dances for our people?"

After much conferring, the Elder Priests arranged to send our Wise Ones to visit the God of Dew. Next day the four Wise Ones set out upon their mission.

Slowly climbing a steep trail, they were pleased to hear music coming from the high Sacred Mountain. Near the top, they discovered that the music came from the Cave of the Rainbow. At the cave's entrance vapors floated about, a sign that within was the god Paiyatuma.

When the four Wise Ones asked permission to go in, the music stopped; however, they were welcomed warmly by Paiyatuma, who said, "Our musicians will now rest while we learn why you have come."

"Our Elders, the Priests of the Bow, directed us to you. We wish for you to show us your secret in making new sounds of music. Also with the new music, we wish to learn how to create new ceremonial dances.

"As gifts, our Elders have prepared these prayer sticks and special plume-offerings for you and your people."

"Come sit with me," responded Paiyatuma. "You shall now see and hear."

Before them appeared many musicians with beautifully decorated long shirts. Their faces were painted with the signs of the gods. Each held a lengthy tapered flute. In the centre of the group was a large drum beside which stood its drum-beater. Another musician held the conductor's wand. These were men of age and experience, graced with dignity.

Paiyatuma stood and spread some magic pollen at the feet of the visiting Wise Ones. With crossed arms, he then strode the length of the cave, turning and walking back again. Seven beautiful young girls, tall and slender, followed him. Their garments were similar to the musicians, but were of various colours. They held hollow cottonwood shafts from which bubbled dainty clouds when the maidens blew into them.

"These are not the maidens of corn," Paiyatuma said. "They are our dancers, the young sisters from the House of Stars."

Paiyatuma placed a flute to his lips and joined the circle of dancers. From the drum came a thunderous beat, shaking the entire Cave of the Rainbow, signalling the performance to begin.

Beautiful music from the flutes seemed to sing and sigh like the gentle blowing of the winds. Bubbles of vapour arose from the girls' reeds. In rhythm, the Butterflies of Summerland flew about the cave, creating their own dance forms with the dancers and the musicians. Mysteriously, over all the scene flooded the colours of the Rainbow throughout the cave. All of this harmony seemed like a dream to the four Wise Ones, as they thanked the God of Dew and prepared to leave.

Paiyatuma came forward with a benevolent smile and symbolically breathed upon the four Wise Ones. He summoned four musicians, asking them to give each one a flute as a gift. "Now depart to your Elders," said Paiyatuma. "Tell them what you have seen and heard. Give them our flutes. May your people the Zunis learn to sing like the birds through these woodwinds and these reeds." In gratitude the Wise Ones bowed deeply and accepted the gifts, expressing their appreciation and farewell to all of the performers and Paiyatuma.

Upon the return of the four Wise Ones to their own ceremonial court, they placed the four flutes before the Priests of the Bow. The Wise Ones described and demonstrated all that they had seen and heard in the Cave of the Rainbow.

Chief of the Zuni tribe and his counsellors were happy with their new knowledge, returning to their tribe with the gift of the flutes and the reeds. Before their next ceremonial, many of their tribesmen learned to make new music and to create new dances for all their people to enjoy.

Not far from Rainbow Cave on the Sacred Mountain in what is now New Mexico, Hummingbird Hoya lived with his beloved grandmother long ago.

"I think I will go to Kiakima to see what their clansmen are doing," Hoya said one day to his beloved grandmother.

Because he was so small and wanted to be sure that people could see him, Hoya dressed himself in his colourful hummingbird coat and flew far away. Below him, he saw a lovely spring and decided to stop, taking off his beautifully feathered coat.

Before long, Kia, the daughter of Chief Kya-ki-massi, arrived to fill her jar with the cool spring water. Many young men of the Zuni Indian tribe longed to marry Kia, but were afraid to ask her father, the Chief.

Kia began to fill her water jar without speaking to the attractive young man nearby.

"May I have some of your water to drink?" Hoya asked.

Kia handed him a cupful. When he returned the cup to her, a small amount of water remained. Playfully, she tossed it to him and giggled.

Some young Zunis watching from the brush wondered why she laughed. They also wondered about the stranger. Then they heard the princess say, "Let's go to my home."

Hoya followed Kia to her house, and they talked for some time at the bottom of her ladder, which led to the lodge roof. Then Hoya said, "I think it is time for me to start home."

"I hope to see you at the spring tomorrow," Kia said. She then climbed to the roof of her lodge. Hoya put on his magic feathered coat, flying away invisibly. The young men of the village did not see Hoya vanish, which aroused their curiosity.

When Hoya arrived back at his beloved grandmother's house, she met him with a bowl of honey combined with sunflower pollen. The next day, he carried some of the delicacy to the spring as a gift for the princess. Again, he walked Kia home and they conversed at the bottom of her ladder. He gave her the honey and pollen to share with her family.

"Um-m-m good, we like this kind of food," her parents said. "You should marry this young man."

Next day, when Hoya walked Kia home from the spring, she invited him to come into her lodge to meet her family.

"No, thank you, Kia, I cannot marry you yet," said Hoya. "I do not have deerskins, blankets, or beads for you."

"But I do not need these things," she replied. "I like the good food you brought to me, that is enough."

"Then, if I may, I will come to your lodge tomorrow evening," said Hoya. He then put on his magic coat and flew away instantly as Kia ascended the ladder to her roof.

Hoya reported to his beloved grandmother all that had taken place. He told her the Chief's daughter wanted him for her husband.

"No, not now," she replied. "You do not have enough things to give her; you cannot marry her yet."

"But, Grandmother, the daughter of the Chief wants nothing except our delicious honey food."

"If you are sure of her parents' approval, then I give you my permission to marry Kia."

At dawn next day, Hoya and his beloved grandmother, dressed in their hummingbird coats, zoomed away southward to the land of the sunflowers.

All that day, they gathered pollen and honey. Later, when they returned, they placed a deerskin on the floor. Onto this, they shook the pollen from their feathers. Into a large shell, they deposited the honey. Hoya's beloved grandmother mixed the pollen and honey together, much the same way as kneading bread dough. She then wrapped a large ball of the mixture in a deerskin, which Hoya took to Kia that very evening.

Village youths gathered and watched from a distance as Hoya climbed Kia's ladder to her lodge roof. There Hoya secretly hid his magic coat under a rock before lowering himself into Kia's lodge.

"How sad for us that Kia will marry a stranger," the youths repeated among themselves.

The young men of Zuni village gathered in a Kiva, a ceremonial lodge saying to the Bow Chief, "Please announce that in four days we will go on a parrot hunt. Say, also, that anyone who does not join us will lose his wife."

Later, Kia's brother returned home and reported, "In the village, they are saying that on the hunt for young parrots, the young hunters will throw my new brother-in-law from the mesa and kill him. they will then claim his wife."

"They are just loud-mouth talking," said Chief Kya-ki-massi.

But Hoya believed that when he heard from younger brother. He quickly put on his hummingbird coat and flew away to Parrot Woman's Cave.

"What have you to say?" she asked.

"I wish to warn you to protect your young parrots from harm. I also ask your help for myself," Hoya said, telling her of the plot to kill him. In a few minutes, he returned to Kia's home.

Next day, the parrot hunt began, with Hoya bringing up the rear. He secretly wore his magic coat beneath his buckskin shirt. At the high mesa, a yucca rope was let down toward the parrot's cave.

Hoya was instructed by the group to go down the rope to the nest of the young parrots. When he was halfway down, the village hunters let go of the rope. Parrot Woman was waiting for him, spreading her large fanlike tail outside her cave entrance. She caught Hoya in time.

Upon returning to the village, the young men reported that the rope broke, letting hoya fall to his death. In Kia's lodge, there was much sadness at the loss of Kia's new husband.

Parrot Woman took her two young birds and, with Hoya in his magic coat, flew up to the mesa.

"Please keep my two children with you," she said. "But bring them back to me in four days."

Hoya took the two young parrots to his new home and, from the roof he heard Kia crying inside.

"I hear someone on our roof," her father said. "Perhaps, it is your new husband."

"Impossible," said his son. "Hoya is dead. But Kia ran up the ladder and to her great joy, she discovered her husband with the two parrots.

At dawn, Hoya placed the two young parrots on the tips of the ladder poles. A village youth came out of the Kiva and saw the birds. He ran back inside calling, "Wake up everyone! Hoya is not dead. He has come back to his home with two young parrots!"

When the Zuni villagers saw the two parrots, they decided to make another plan to rid themselves of Hoya.

"Please, Bow Chief, give us permission to hunt the Bear's children. If anyone does not come along with us, he will lose his wife."

Hoya heard the terrible news, so he went to the cave of the Bear Mother.

"What do you wish of me?" she asked Hoya.

"The young hunters of Zuni village are going on a hunt for your children. I have come to warn you and to ask you for your help in protecting me," replied Hoya. Then he told her of the plot to kill him.

Four days later, the young hunters charged toward Bear Mother's cave. Hoya again secretly wore his magic hummingbird coat beneath his buckskin shirt. He was forced by the young men to lead the attack at the cave entrance. Then the others pushed him inside the Bear's cave!

Mother Bear grabbed him but she shoved him behind her. She chased the young Zuni hunters, killing a few of the young tribesmen. Later, Hoya flew home with two bear cubs and at dawn he placed them on the roof. When the villagers discovered the bears on Kia's roof, they knew that Hoya was still alive.

Hoya decided to fly to his beloved grandmother's home near Rainbow Cave to seek her wisdom about a new plan of his. She helped him paint a bird cage with many colours and they filled it with birds of matching colours. Back to Zuni village he flew, carrying the cage, which he placed in the centre of the plaza. Around it, he planted magic corn, bean, squash, and sunflower seeds.

That very evening welcome rains came down gently. Next morning the sun shone brightly and warmly. When the Zuni villagers came out of their adobe houses, they were amazed at the sight before them! In the plaza centre, growing plants surrounded the beautiful cage of colourful, singing birds!

From that moment on, all of the happy, dancing Zuni tribe accepted Hoya and his gifts. They learned to love him as one of their own. His wife they called Mother, and they called him Father of their tribe for many contented years.

In the long ago time there was only one Tarantula on earth. He was as large as a man, and lived in a cave near where two broad columns of rock stand at the base of Thunder Mountain. Every morning Tarantula would sit in the door of his den to await the sound of horn bells which signalled the approach of a young Zuni who always came running by at sunrise. The young man wore exceedingly beautiful clothing of red, white and green, a plaited headband of many colours, a plume of blue, red and yellow macaw feathers in his hair knot, and a belt of horn bells. Tarantula was most envious of the young man, and spent much time thinking of ways to obtain his costume through trickery.

Swift-Runner was the young Zuni's name, and he was studying to become a priest-chief like his father. His costume was designed for use in sacred dances. To keep himself strong for these arduous dances, Swift-Runner dressed in his sacred clothing every morning and ran all the way around Thunder Mountain before prayers.

One morning at sunrise, Tarantula heard the horn bells rattling in Swift-Runner's belt. He took a few steps outside of his den, and as the young Zuni approached, he called out to him: "Wait a moment, my young friend, Come here!"

"I'm in a great hurry," Swift-Runner replied.

"Never mind that. Come here," Tarantula repeated.

"What is it?" the young man asked impatiently. "Why do you want me to stop?"

"I much admire your costume," said Tarantula. "Wouldn't you like to see how it looks to others?"

"How is that possible?" asked Swift-Runner.

"Come, let me show you."

"Well, hurry up. I don't want to be late for prayers."

"It can be done very quickly," Tarantula assured him. "Take off your clothing, all of it. Then I will take off mine. Place yours in front of me, and I will place mine in front of you. Then I will put on your costume, and you will see how handsome you look to others."

If Swift-Runner had known what a trickster Tarantula was, he would never have agreed to this, but he was very curious as to how his costume appeared to others. He removed his red and green moccasins, his fringed white leggings, his belt of horn bells, and all his other fine clothing, and placed them in front of Tarantula.

Tarantula meanwhile had made a pile of his dirty woolly leggings, breech-cloth and cape--all of an ugly grey-blue colour. He quickly began dressing himself in the handsome garments that Swift-Runner placed before him, and when he was finished he stood up on his crooked hind legs and said: "Look at me now. How do I look?"

"Well," replied Swift-Runner, "so far as the clothing is concerned, quite handsome."

"You can get a better idea of the appearance if I back off a little farther," Tarantula said, and he backed himself, as only Tarantulas can, toward the door of his den. "How do I look now?"

"Handsomer," said the young man.

"Then I'll get back a little farther." He walked backward again. "Now then, how do I look?"

"Perfectly handsome."

"Aha!" Tarantula chuckled as he turned around and dived headfirst into his dark hole.

"Come out of there!" Swift-Runner shouted, but he knew he was too late.

Tarantula had tricked him. "What shall I do now?" he asked himself. "I can't go home half naked." The only thing he could do was put on the hairy grey-blue clothing of Tarantula, and make his way back to the village.

When he reached home the sun was high, and his father was anxiously awaiting him. "What happened?" his father asked. "Why are you dressed in that ugly clothing?"

"Tarantula who lives under Thunder Mountain tricked me," Swift- Runner replied. "He took my sacred costume and ran away into his den."

His father shook his head sadly. "We must send for the warrior chief," he said. "He will advise us what we must do about this."

When the warrior-chief came, Swift-Runner told him what had happened. The chief thought for a moment, and said: "Now that Tarantula has your fine costume, he is not likely to show himself far from his den again. We must dig him out."

And so the warrior-chief sent runners through the village, calling all the people to assemble with hoes, digging sticks, and baskets. After the Zunis gathered with all these things, the chief led the way out to the den of Tarantula.

They began tunnelling swiftly into the hole. They worked and worked from morning till sundown, filling baskets with sand and throwing it behind them until a large mound was piled high. At last they reached the solid rock of the mountain, but they found no trace of Tarantula. "What more can we do?" the people asked. "Let us give up because we must. Let us go home." And so as darkness fell, the Zunis returned to their village.

That evening the leaders gathered to discuss what they must do next to recover Swift-Runner's costume. Someone suggested that they send for the Great Kingfisher. "He is wise, crafty, and swift of flight. If anyone can help us, the Great Kingfisher can."

"That's it," they agreed. "Let's send for the Kingfisher."

Swift-Runner set out at once, running by moonlight until he reached the hill where Great Kingfisher lived, and knocked on the door of his house.

"Who is it?" called Kingfisher.

"Come quickly," Swift-Runner replied. "The leaders of our village seek your help."

And so Kingfisher followed the young man back to the Zuni council. "What is it that you need of me?" he asked.

"Tarantula has stolen the sacred garments of Swift-Runner," they told him. "We have dug into his den to the rock foundation of Thunder Mountain, but we can dig no farther, and know not what next to do. We have sent for you because of your power and ability to snatch anything, even from underwater."

"This is a difficult task you place before me," said Kingfisher. "Tarantula is exceedingly cunning and very sharp of sight. I will do my best, however, to help you."

Before sunrise the next morning, Kingfisher flew to the two columns of rock at the base of Thunder Mountain and concealed himself behind a stone so that only his beak showed over the edge. As the first streaks of sunlight came over the rim of the world, Tarantula appeared in the entrance of his den. With his sharp eyes he peered out, looking all around until he sighted Kingfisher's bill. "Ho, ho, you skulking Kingfisher!" he cried.

At the instant he knew he was discovered, Kingfisher opened his wings and sped like an arrow on the wind, but he merely brushed the tips of the plumes on Tarantula's head before the trickster jumped back deep into his hole. "Ha, ha!" laughed Tarantula. "Let's have a dance and sing!" He pranced up and down in his cave, dancing a tarantella on his crooked legs, while outside the Great Kingfisher flew to the Zuni village and sadly told the people: "No use! I failed completely. As I said, Tarantula is a crafty, keen-sighted old fellow. I can do no more."

After Kingfisher returned to his hill, the leaders decided to send for Great Eagle, whose eyes were seven times as sharp as the eyes of men. He came at once, and listened to their pleas for help. "As Kingfisher, my brother, has said, Tarantula is a crafty, keen sighted creature. But I will do my best."

Instead of waiting near Thunder Mountain for sunrise, Eagle perched himself a long distance away, on top of Badger Mountain. He stood there with his head raised to the winds, turning first one eye and then the other on the entrance to Tarantula's den until the old trickster thrust out his woolly nose. With his sharp eyes, Tarantula soon discovered Eagle high on Badger Mountain. "Ho, you skulking Eagle!" he shouted, and Eagle dived like a hurled stone straight at Tarantula's head. His wings brushed the trickster, but when he reached down his talons he clutched nothing but one of the plumes on Tarantula's headdress, and even this fell away upon the rocks. While Tarantula laughed and danced in his cave and told himself what a clever well- dressed fellow he was, the shamed and disappointed Eagle flew to the Zuni council and reported his failure.

The people next called upon Falcon to help them. After he heard of what already had been done, Falcon said: "If my brothers, Kingfisher and Eagle, have failed, it is almost useless for me to try."

"You are the swiftest of the feathered creatures," the leaders answered him. "Swifter than Kingfisher and as strong as Eagle. Your plumage is speckled grey and brown like the rocks and sagebrush so that Tarantula may not see you."

Falcon agreed to try, and early the next morning he placed himself on the edge of the high cliff above Tarantula's den. When the sun rose he was almost invisible because his grey and brown feathers blended into the rocks and dry grass around him. He kept a close watch until Tarantula thrust out his ugly face and turned his eyes in every direction. Tarantula saw nothing, and continued to poke himself out until his shoulders were visible. At that moment Falcon dived, and Tarantula saw him, too late to save the macaw plumes from the bird's grasping claws.

Tarantula tumbled into his den, sat down, and bent himself double with fright. He wagged his head back and forth, and sighed: "Alas, alas, my beautiful headdress is gone. That wretch of a falcon! But what is the use of bothering about a miserable bunch of macaw feathers, anyway? They get dirty and broken, moths eat them, they fade. Why trouble myself about a worthless thing like that? I still have the finest costume in the Valley-handsome leggings and embroidered shirt, necklaces worth fifty such head- plumes, and earrings worth a handful of such necklaces. Let Falcon have the old head-plumes."

Meanwhile, Falcon, cursing his poor luck, took the feathers back to the Zunis. "I'm sorry, my friends, this is the best I could do. May others succeed better."

"You have succeeded well," they told him. "These plumes from the South are precious to us."

Then the leaders gathered in council again. "What more is there to be done?" Swift-Runner's father asked.

"We must send your son to the land of the gods," said the war chief "Only they can help us now."

They called Swift-Runner and said to him: "We have asked the wisest and swiftest and strongest of the feathered creatures to help us, yet they have failed. Now we must send you to the land of the gods to seek their help."

Swift-Runner agreed to undertake the dangerous climb to the top of Thunder Mountain where the two war-gods, Ahaiyuta and Matsailema, lived with their grandmother. For the journey, the priest-chiefs prepared gifts of their most valuable treasures. Next morning, Swift-Runner took these with him and by midday he reached the place where the war-gods lived.

He found their grandmother seated on the flat roof of their house. From the room below came the sounds of the war-gods playing one of their noisy games. "Enter, my son," the grandmother greeted Swift-Runner, and then she called to Ahaiyuta and Matsailema: "Come up, my children, both of you, quickly. A young man has come bringing gifts."

The war-gods, who were small like dwarfs, climbed to the roof and the oldest said politely: "Sit down and tell us the purpose of your visit. No stranger comes to the house of another for nothing."

"I bring you offerings from our village below. I also bring my burden of trouble to listen to your counsel and implore your aid."

He then told the war-gods of his misfortunes, of how Tarantula had stolen his sacred clothing, and of how the wisest and swiftest of the feathered beings had tried and failed to regain them.

"It is well that you have come," said the youngest war-god. "Only we can outwit the trickster Tarantula. Grandmother, please bestir yourself, and grind some rock flour for us."

While Swift-Runner watched, the old grandmother gathered up some white sandstone rocks, broke them into fragments, and then ground them into a powder. She made dough of this with water, and the two war-gods, with amazing skill, moulded the dough into two deer and two antelope which hardened as quickly as they finished their work.

They gave the figures to Swift-Runner and told him to place them on a rock shelf facing the entrance to Tarantula's den. "Old Tarantula is very fond of hunting. Nothing is so pleasing to him as to kill wild game. He may be tempted forth from his hiding place. When you have done this, go home and tell the chiefs that they should be ready for him in the morning."

That evening after Swift-Runner returned to his village and told how he had placed the figures of deer and antelope on the rock shelf in front of Tarantula's den, the chiefs summoned the warriors and told them to make ready for the warpath before sunrise. All night long they prepared their arrows and tested the strength of their bows, and near dawn they marched out to Thunder Mountain. Swift-Runner went ahead of them, and when he approached the rock shelf, he was surprised to see that the two antelope and the two deer had come to life. They were walking about, cropping the tender leaves and grass.

"I call upon you to help me overcome the wicked Tarantula," he prayed to the animals. "Go down close to his den, I beg you, that he may be tempted forth at the sight of you."

The deer and antelope obediently started down the slope toward Tarantula's den. As they approached the entrance, Tarantula sighted them. "Ho! What do I see?" he said to himself "There go some deer and antelope. Now for a hunt. I might as well get them as anyone else."

He took up his bow, slipped the noose over the head of it, twanged the string, and started out. But just as he stepped forth from his den, he said to himself: "Good heavens, this will never do! The Zunis will be after me if I go out there." He looked up and down the valley. "Nonsense! There's no one about." He leaped out of his hole and hurried toward the deer, which were still approaching. When the first one came near he drew back an arrow and let fly. The deer dropped at once. "Aha!" he cried. "Who says I am not a good hunter?" He whipped out another arrow and shot the second deer. With loud exclamations of delight, he then felled the two antelope.

"What fine game I have bagged today," he said. "Now I must take the meat into my den." He untied a strap which he had brought along and with it he lashed together the legs of the first deer he had shot. He stooped, raised the deer to his back, and was about to rise with the burden and start for his den, when cachunk! he fell down almost crushed under a mass of white rock. "Mercy!" he cried. "What's this?" He looked around but could see no trace of the deer, nothing but a shapeless mass of white rock.

"Well, I'll try this other one," he said, but he had no sooner lifted the other deer to his back when it knocked him down and turned into another mass of white rock. "What can be the matter?" he cried.

Then he tried one of the antelope and the same thing happened again. "Well, there is one left anyway," he said. He tied the feet of the last animal and was about to lift it when he heard a great shouting of many voices.

He turned quickly and saw all the Zunis of the village gathering around his den. He ran for the entrance as fast as his crooked legs would move, but the people blocked his way. They closed in upon him, they clutched at his stolen garments, they pulled earrings from his ears, until he raised his hands and cried: "Mercy! Mercy! You hurt! You hurt! Don't treat me so! I'll be good hereafter. I'll take this costume off and give it back to you without making the slightest trouble if you will only let me alone." But the people closed in angrily. They pulled him about and stripped off Swift Runner's costume until Tarantula was left unclothed and so bruised that he could hardly move.

Then the chiefs gathered around, and one of them said: "It will not be well if we let this trickster go as he is. He is too big and powerful, too crafty. To rid the world of Tarantula forever, he must be roasted!"

And so the people piled dry firewood into a great heap, drilled fire from a stick, and set the wood to blazing. They threw the struggling trickster into the flames, and he squeaked and sizzled and hissed and swelled to enormous size. But Tarantula had one more trick left in his bag. When he burst with a tremendous noise, he threw a million fragments of himself all over the world-to Mexico and South America and as far away as Taranto in Italy. Each fragment took the shape of Old Tarantula, but of course they were very much smaller, somewhat as tarantulas are today. Some say that Taranto took its name from the tarantulas, some say the tarantulas took their name from Taranto, but everybody knows that the wild dance known as the tarantella was invented by Tarantula, the trickster of Thunder Mountain, in the land of the Zunis. Zuni