Yoga balances brain chemistry and makes people for better, if only for a short time. I highly recommend it to clients who suffer from emotional problems, especially bipolar disorder. In meditation, people often lose their focus, become relaxed, then fall asleep, sometimes without knowing it. With Yoga, that is generally not the case. There is more mind-body interaction.

Yoga is a form of mysticism that developed on the Indian subcontinent in the Hindu cultural context. Its origin is impossible to trace, because it dates back to before recorded history. Yoga comes in many forms specifically designed to suit different types of people. As a result, some forms of yoga have gained significant popularity outside India, particularly in the West during the past century.

The word Yoga originates from the Sanskrit word "Yuj" (literally, "to yoke") and is generally translated as "union" - "integration" - to yoke, attach, join, unite. Yoga is therefore the union and integration of every aspect of a human being, from the innermost to the external. According to Yoga experts, the union referred to by the name is that of the individual soul with the cosmos, or the Supreme.

Yoga has both a philosophical and a practical dimension. The philosophy of yoga ("union") deals with the nature of the individual soul and the cosmos, and how the two are related. The practice of yoga, on the other hand, can be any activity that leads or brings the practitioner closer to this mystical union - a state called self-realization. Over thousands of years, special practical yoga techniques have been developed by experts in yoga, who are referred to as Yogis (male) and Yoginis (female).

These Yoga techniques cover a broad range, encompassing physical, mental, and spiritual activities. Traditionally, they have been classified into four categories or paths: the path of meditation (Raja Yoga), the path of devotion (Bhakti Yoga), the path of selfless service to the Divine (Karma Yoga), and the path of intellectual analysis or the discrimination of truth and reality (Jnana Yoga). The most conspicuous form of yoga in the West, Hatha Yoga - consisting of various physical and breathing exercises and purification techniques - is actually the third and the fourth stages of Ashtanga Yoga of Yoga Sutras by Patanjali.

Clients and friends enjoy Yoga as means of bringing balance into their lives. They report greater clarity in their meditations and a sense of releasing issues that hold them back.

Yoga enhances every facet of physical fitness the mind/body energy exchange supports a mental clarity and concentration. The strength improves posture/alignment to support our daily activities. The flexibility helps to prevent injuries and keeps us supple and youthful. The breathing practices are the foundation and the link between the mind and the body, providing a valuable tool for releasing tension and reducing stress.

The practice of yoga teaches us how to quiet the mind by placing attention on the breath, and also on the movement (stillness) of the body.

The history of yoga may go back anywhere from five to eight thousand years ago, depending on the perspective of the historian. It evolved wholly in the land of India, and while it is supposed by some scholars that yogic practices were originally the domain of the indigenous, non-Aryan (and pre-Vedic) peoples, it was first clearly expounded in the great Vedic shastras (religious texts).

Pre-Vedic findings are taken, by some commentators, to show that "yoga" existed in some form well before the establishment of Aryan culture in the north Indian subcontinent.

A triangular amulet seal uncovered at the Mohenjo-daro archeological excavation site depicts a male, seated on a low platform in a cross legged position, with arms outstretched. His head is crowned with the horns of a water-buffalo. He is surrounded by animals (a fish, an alligator, and a snake) and diverse symbols. The likeness on the seal and understandings of the surrounding culture have led to its widely accepted identification as "Pashupati", Lord of the Beasts, a prototype and predecessor of the modern day Hindu god Shiva. The pose is a very familiar one to yogins, representing Shiva much as he is seen today, the meditating ascetic contemplating divine truth in "yoga-posture."

David Frawley, a Vedic scholar, writes: "Yoga can be traced back to the Rig Veda itself, the oldest Hindu text which speaks about yoking our mind and insight to the Sun of Truth. Great teachers of early Yoga include the names of many famous Vedic sages like Vasishta, Yajnavalkya, and Jaigishavya.

"Ideas of uniting mind, body and soul in the cosmic one, however, do not find real yogic explication until the most important mystic texts of Hinduism, the Upanishads or Vedanta, commentaries on the Vedas.

Explicit examples of the concept and terminology of yoga appear in the Upanishads (primarily thirteen principal texts of the Vedanta, or the "End of the Vedas," that are the culmination of all Vedic philosophy)While protracted discussions of the ultimate, infinite Self, or Atman, and realization of Brahman, are the true legacy of the Upanishads, the first principal Yoga text was the Bhagavad Gita ("The Lord's Song"), also known as Gitopanishad.

In the Maitrayaniya Upanishad (ca. 200-300 BCE) yoga surfaces as:"Shadanga-Yoga - The uniting discipline of the six limbs (shad-anga), as expounded in the Maitrayaniya-Upanishad: (1) breath control (pranayama), (2) sensory inhibition (pratyahara), (3) meditation (dhyana), (4) concentration (dharana), (5) examination (tarka), and (6) ecstasy (samadhi).

After the Bhagavad Gita, the next seminal work on Yoga is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. The Yoga Sutras are a compilation of Yogic thought that is largely Raja Yogic in nature, it was codified some time between the 2nd century BC and the 3rd century by Patanjali, and prescribes adherence to "eight limbs" (the sum of which constitute "Ashtanga Yoga") to quiet one's mind and merge with the infinite. These eight limbs not only systematized conventional moral principles espoused by the Gita, but elucidated the practice of Raja Yoga in a more detailed manner. Indeed, his "eight-limbed" path has formed the foundation for Raja Yoga and much of Tantra Yoga (a Hindu deific, Shiva-Shakti yoga system) and Vajrayana Buddhism (Buddhist Tantra Yoga) that came after. It goes as follows:

Asana (posture)

Pranayama (breath control)

Pratyahara (sense control)

Dharana (concentration)

Dhyana (contemplation)

Samadhi (veridical meditation)

Patanjali, whose own life is virtually unknown, had the impact of further spreading in compact form the essence of Raja Yoga. Some legends speak of his being Adinaga, the first snake, the lower half of his body being that of a snake, upon which the great Hindu God Vishnu reclines. Many say that he was the same Patanjali who wrote commentaries on Panini's singular masterwork on Sanskrit grammar. Others speak of the legends of his birth. A few even dispute his existence and attribute the Yoga Sutras to many authors, but this is highly unlikely due to the structural, linguistic and stylistic uniformity of the short work. His base is Hindu Samkhya philosophy and shows itself to have been highly influenced by the Upanishads.

His Yoga Sutras espouse a threefold system for attainment of samadhi through tapas (austerities; discipline; literally "heat"), swadhyaya (self-study) and ishwar-pranidhana (contemplation of God).While Patanjali accepts the idea of what he terms "ishta-devata" (worship of deities as manifestations of the single Brahman), his overall "ishwar" is not a conventional God with personal form and speaks more to a universal, attributeless Brahman, an impersonal, unknowable, infinite force that is all and transcends all.

Together, the Bhagavad Gita and Yoga Sutras form the theoretical and philosophical base of all yoga. However, as far as Raja Yoga (meditation yoga) goes, it is most precisely captured by Patanjali's Yoga-Sutras.

The Yoga-bhasya, Veda Vyasa's commentary on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali could have been written as early as 450 CE. Professor J. H. Woods, places the date of the Yoga-bhasya between 650 CE to 850 CE. Trevor Leggett places the date closer to 600 CE based on a commentary to the Yoga-bhasya published in Sanskrit in 1952 in the Madras Government Oriental Series #94 by Polakam Sri Rama Sastri and S. R. Krishnamurti Sastri. Evidence strongly suggests that this sub-commentary was written by Sankara who lived about 700 CE.

Hatha Yoga Pradipika In the West, outside of Hindu culture, "yoga" is usually understood to refer to "hatha yoga." Hatha Yoga is, however, a particular system propagated by Swami Swatamarama, a yogic sage of the 15th century in India.

After the Bhagavad Gita and Yoga Sutras, the most fundamental text of Yoga is the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, written by Swami Swatamarama, that in great detail lists all the main asanas, pranayama, mudra and bandha that are familiar to today's yoga student. It runs in the line of Hindu yoga (to distinguish from Buddhist and Jain yoga) and is dedicated to Lord Adinath, a name for Lord Shiva (the Hindu god of destruction), who is alleged to have imparted the secret of Hatha Yoga to his divine consort Parvati. It is common for yogins and tantriks of several disciplines to dedicate their practices to a deity under the Hindu ishta-devata concept while always striving to achieve beyond that: Brahman.

Hindu philosophy in the Vedanta and Yoga streams, as the reader will remember, views only one thing as being ultimately real: Satchidananda Atman, the Existence-Consciousness-Blissful Self. Very Upanishadic in its notions, worship of Gods is a secondary means of focus on the higher being, a conduit to realization of the Divine Ground. Hatha Yoga follows in that vein and thus successfully transcends being particularly grounded in any one religion.

Hatha is a Sanskrit word meaning 'sun' (ha) and 'moon' (tha), representing opposing energies: hot and cold, male and female, positive and negative, similar but not completely analogous to yin and yang. Hatha yoga attempts to balance mind and body via physical exercises, or "asanas", controlled breathing, and the calming of the mind through relaxation and meditation. Asanas teach poise, balance & strength and were originally (and still) practiced to improve the body's physical health and clear the mind in preparation for meditation in the pursuit of enlightenment. "Asana" means "immovable", i.e. static, and often confused with the dynamic 108 natya karanas described in Natya Shastra and, along with the elements of Bhakti Yoga, is embodied in the contemporary form of Bharatanatyam.

By balancing two streams, often known as ida (mental) and pingala (bodily) currents, the sushumna nadi (current of the Self) is said to rise, opening various chakras (cosmic power points within the body, starting from the base of the spine and ending right above the head) until samadhi is attained. Ida and pingala are represented in the dynamism of natya yoga by lasya (female) and tandava (male) aspects, and bear direct reference to the Taoist dualism.

By forging a powerful depth of concentration and mastery of the body and mind, Hatha Yoga practices seek to still the mental waters and allow for apprehension of oneself as that which one always was, Brahman. Hatha Yoga is essentially a manual for scientifically taking one's body through stages of control to a point at which one-pointed focus on the unmanifested Brahman is possible: it is said to take its practitioner to the peaks of Raja Yoga.

In the West, hatha yoga has become wildly popular as a purely physical exercise regimen divorced of its original purpose, and thus, devoid of its original efficacy. Currently, it is estimated that about 30 million Americans practice hatha yoga. But in the Indian subcontinent the traditional practice is still to be found.

The guru-shishya (teacher-student) relationship that exists without need for sanction from non-religious institutions, and which gave rise to all the great yogins who made way into international consciousness in the 20th century, has been maintained in Indian, Nepalese, and some Tibetan circles.

In India, whose Hindu population combines to a staggering 800 million, Yoga is a daily part of life. It is common to see people performing Surya Namaskar (a yogic set of asanas and pranayam dedicated to Surya, the Hindu God of the Sun) in the morning or speaking about food diets and body therapy entirely based on Yoga or the Hindu healing system of Ayurveda.

The age-old tradition of Yoga has continued uninterrupted by the its popularity in the west (although more established schools like the Bihar School of Yoga work from within India to produce Yoga texts to send abroad).

In addition, hundreds and thousands sanyasins (renunciates) and sadhus (Hindu monks) wander in and out of city temples, village country sides and are to be found smattered all across the foothills of the Himalaya and the Vindhya Range of central India.

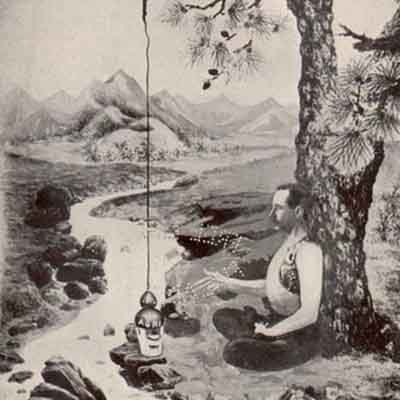

For India's holy-men, Yoga is as fundamental as lifeblood. To see a man meditating at the steps of a temple, or even wondering contemplatively on the roadside, is not uncommon even to the more Westernized crowds. It is the same in Tibet, where the Buddhist establishment's lifestyle is permeated with the Yoga or yogic practices, which is ultimately not a once-a-day routine, but a constant immersion in self-discovery.

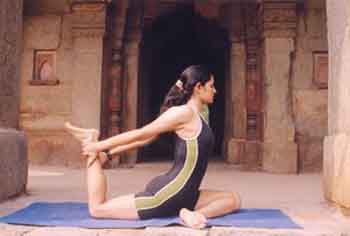

Asana - orbiting down) is a body position, typically associated with the practice of Yoga, originally identified as a mastery of sitting still, with the spine as a conduit of biodynamic union.

In the context of Yoga practice, asana refers to two things: the place where a practitioner (yogin (general usage); yogi (male); yogini (female)) sits and the manner (posture) in which he/she sits.

In the Yoga sutras, Patanjali suggests that asana is "to be seated in a position that is firm, but relaxed" for extended, or timeless periods.

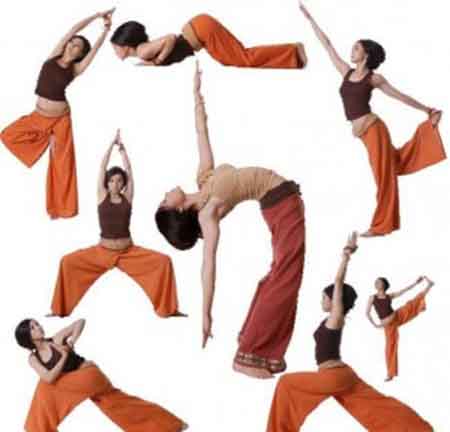

As a repertoire of postures were promoted to exercise the body-mind over the centuries, to the present day when yoga is sought as a primarily physical exercise form, modern usage has come to include variations from lying on the back and standing on the head, to a variety of other positions.

However, in the Yoga sutras, Patanjali mentions the execution of sitting with a steadfast mind for extended periods as the third of the eight limbs of Classical or Raja yoga, but does not reference standing postures or kriyas.

Yoga practitioners (even those who are adepts at various complex postures) who seek the "simple" practice of chair-less sitting generally find it impossible or surprisingly grueling to sit still for the traditional minimum of one-hour (as still practiced in eastern Vipassana), some of them then dedicating their practice to sitting asana and the sensations and mind-states that arise and evaporate in extended sits.

Asana later became a term for various postures useful for restoring and maintain a practitioner's well-being and improve the body's flexibility and vitality, with the goal to cultivate the ability to remain in seated meditation for extended periods.

Asanas are widely known as Yoga postures or Yoga positions, but specifically translates to "pose you can hold with ease", which is not true for everyone. By this definition, practices where the participant is not at ease do not qualify as asana.

Yoga in the West is commonly practiced as physical exercise or alternative medicine, rather than as the spiritual self-mastery meditation skill it is more associated with in the East.

In 1959, Swami Vishnu-devananda published a compilation of 66 basic postures and 136 variations of those postures.

In 1975, Sri Dharma Mittra suggested that "there are an infinite number of asanas.", when he first began to catalogue the number of asanas in the Master Yoga Chart of 908 Postures, as an offering of devotion to his guru Swami Kailashananda Maharaj.

He eventually compiled a list of 1300 variations, derived from contemporary gurus, yogis, and ancient and contemporary texts. This work is considered one of the primary references for asanas in the field of yoga today. His work is often mentioned in contemporary references for Iyengar Yoga, Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, Sivananda Yoga, and other classical and contemporary texts.

In 2007, public awareness of increasing attempts to patent traditional yoga postures in the US, including 130 yoga-related patents in the US documented that year, prompted the government of India to seek clarification on the guidelines for patenting asanas from the US Patent Office.

To clearly show that all asanas are public knowledge and therefore not patentable, in 2008, the government of India formed a team of yoga gurus, government officials, and 200 scientists from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) to register all known asanas in a public database. The team collected asanas from 35 ancient texts including the Hindu epics, the Mahabharata, the Bhagwad Gita, and Patanjali's Yoga Sutras and as of 2010, has identified 900 asanas for the database which was named the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library and made available to patent examiners.