Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument located in the English county of Wiltshire, about 3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi) west of Amesbury and 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) north of Salisbury. One of the most famous prehistoric sites in the world, Stonehenge is composed of earthworks surrounding a circular setting of large standing stones. Archaeologists had believed that the iconic stone monument was erected around 2500 BC. However one recent theory has suggested that the first stones were not erected until 2400-2200 BC, while another suggests that bluestones may have been erected at the site as early as 3000 BC.

The surrounding circular earth bank and ditch, which constitute the earliest phase of the monument, have been dated to about 3100 BC. The site and its surroundings were added to the UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites in 1986 in a co-listing with Avebury henge monument, and it is also a legally protected Scheduled Ancient Monument. Stonehenge itself is owned by the Crown and managed by English Heritage while the surrounding land is owned by the National Trust.

New archaeological evidence found by the Stonehenge Riverside Project indicates that Stonehenge served as a burial ground from its earliest beginnings. The dating of cremated remains found that burials took place as early as 3000 B.C, when the first ditches were being built around the monument. Burials continued at Stonehenge for at least another 500 years when the giant stones which mark the landmark were put up.

Stonehenge: DNA reveals origin of builders BBC - April 16, 2019

The ancestors of the people who built Stonehenge travelled west across the Mediterranean before reaching Britain, a study has shown. Researchers compared DNA extracted from Neolithic human remains found across Britain with that of people alive at the same time in Europe. The Neolithic inhabitants appear to have travelled from Anatolia (modern Turkey) to Iberia before winding their way north.

They reached Britain in about 4,000BC.

Stonehenge itself evolved in several construction phases spanning at least some 1500 years. However there is evidence of large scale construction both before and afterwards on and around the monument that perhaps extends the landscape's time frame to 6500 years.

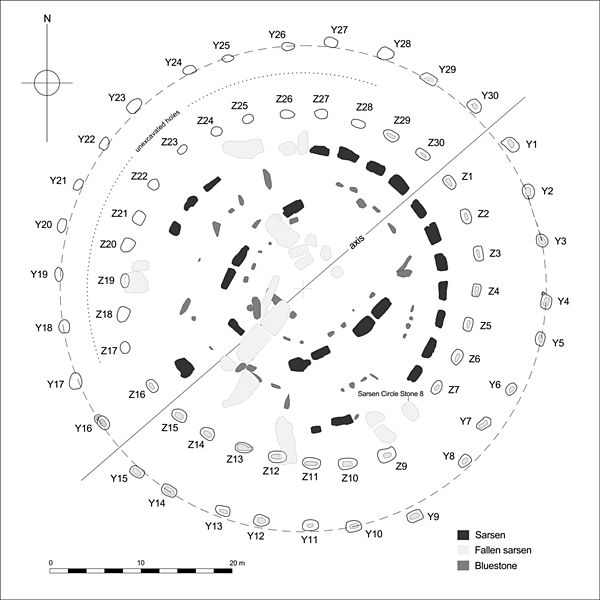

Dating and understanding the various phases of activity at Stonehenge is not a simple task; it is complicated by poorly kept early excavation records, surprisingly few accurate scientific dates and the disturbance of the natural chalk by periglacial effects and animal burrowing. The modern phasing most generally agreed by archaeologists is detailed below. Features mentioned in the text are numbered and shown on the plan, right, which illustrates the site as of 2004. The plan omits the trilithon lintels for clarity. Holes that no longer, or never, contained stones are shown as open circles and stones visible today are shown colored. It is widely assumed that Stonehenge once stood as a magnificent "complete" monument; we should be aware that this cannot be proved, since around half of the stones that should be present are in fact missing, and since many of the assumed stone sockets have never actually been recorded through excavation.

Before the monument (8000 BC forward)

Some archaeologists have found four (or possibly five, although one may have been a natural tree throw) large Mesolithic postholes which date to around 8000 BC nearby, beneath the modern tourist car-park. These held pine posts around 0.75 metres (2.5 ft) in diameter which were erected and left to rot in situ. Three of the posts (and possibly four) were in an east-west alignment and may have had ritual significance; no parallels are known from Britain at the time but similar sites have been found in Scandinavia. At this time, Salisbury Plain was still wooded but four thousand years later, during the earlier Neolithic, a causewayed enclosure at Robin Hood's Ball and long barrow tombs were built in the surrounding landscape. In approximately 3500 BC a large cursus monument was built 700 metres (2,300 ft) north of the site as the first farmers began to clear the forest and exploit the area.

Stonehenge 1 (ca. 3100 BC)

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch enclosure made of Late Cretaceous (Santonian Age) Seaford Chalk, (7 and 8) measuring around 110 metres (360 ft) in diameter with a large entrance to the north east and a smaller one to the south (14). It stood in open grassland on a slightly sloping but not especially remarkable spot. The builders placed the bones of deer and oxen in the bottom of the ditch as well as some worked flint tools. The bones were considerably older than the antler picks used to dig the ditch and the people who buried them had looked after them for some time prior to burial. The ditch itself was continuous but had been dug in sections, like the ditches of the earlier causewayed enclosures in the area.

The chalk dug from the ditch was piled up to form the bank. This first stage is dated to around 3100 BC after which the ditch began to silt up naturally and was not cleared out by the builders. Within the outer edge of the enclosed area was dug a circle of 56 pits, each around 1 metre (3.3 ft) in diameter (13), known as the Aubrey holes after John Aubrey, the seventeenth century antiquarian who was thought to have first identified them. The pits may have contained standing timbers, creating a timber circle although there is no excavated evidence of them. A recent excavation has suggested that the Aubrey Holes may have originally been used to erect a bluestone circle.[6] If this were the case it would advance the earliest known stone structure at the monument by some 500 years. A small outer bank beyond the ditch could also date to this period.

Stonehenge 2 (ca. 3000 BC)

Evidence of the second phase is no longer visible. It appears from the number of postholes dating to this period that some form of timber structure was built within the enclosure during the early 3rd millennium BC. Further standing timbers were placed at the northeast entrance and a parallel alignment of posts ran inwards from the southern entrance. The postholes are smaller than the Aubrey Holes, being only around 0.4 metres (16 in) in diameter and are much less regularly spaced. The bank was purposely reduced in height and the ditch continued to silt up. At least twenty-five of the Aubrey Holes are known to have contained later, intrusive, cremation burials dating to the two centuries after the monument's inception. It seems that whatever the holes' initial function, it changed to become a funerary one during Phase 2. Thirty further cremations were placed in the enclosure's ditch and at other points within the monument, mostly in the eastern half. Stonehenge is therefore interpreted as functioning as an enclosed cremation cemetery at this time, the earliest known cremation cemetery in the British Isles. Fragments of unburnt human bone have also been found in the ditch fill. Late Neolithic grooved ware pottery has been found in connection with the features from this phase providing dating evidence.

Stonehenge 3 I (ca. 2600 BC)

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, timber was abandoned in favor of stone, and two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) were dug in the centre of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known (hence on present evidence are sometimes described as forming 'crescents'), however they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan) only 43 of which can be traced today.

About 2,000 BC, the first stone circle (which is now the inner circle), comprised of small bluestones, was set up, but abandoned before completion. The stones used in that first circle are believed to be from the Prescelly Mountains, located roughly 240 miles away, at the southwestern tip of Wales. The bluestones weigh up to 4 tons each and about 80 stones were used, in all. Given the distance they had to travel, this presented quite a transportation problem.

Modern theories speculate that the stones were dragged by roller and sledge from the inland mountains to the headwaters of Milford Haven. There they were loaded onto rafts, barges or boats and sailed along the south coast of Wales, then up the Rivers Avon and Frome to a point near present-day Frome in Somerset. From this point, so the theory goes, the stones were hauled overland, again, to a place near Warminster in Wiltshire, approximately 6 miles away. From there, it's back into the pool for a slow float down the River Wylye to Salisbury, then up the Salisbury Avon to West Amesbury, leaving only a short 2 mile drag from West Amesbury to the Stonehenge site.

A forgotten stone from a 1924 dig is now steering a long running Stonehenge debate in a clear direction. New analyses of the hand sized Newall boulder point to people, not ice, as the movers of the monument's smaller bluestones Earth.com - September 11, 2025

Source of Stonehenge Bluestone Rocks Identified Live Science - February 24, 2014

Scientists have found the exact source of Stonehenge's smaller bluestones, new research suggests. The stones' rock composition revealed they come from a nearby outcropping, located about 1.8 miles (3 kilometers) away from the site originally proposed as the source of such rocks nearly a century ago. The discovery of the rock's origin, in turn, could help archaeologists one day unlock the mystery of how the stones got to Stonehenge. The work "locates the exact sources of the stones, which highlight areas where archaeologists can search for evidence of the human working of the stones," said geologist and study co-author Richard Bevins of the National Museum of Wales.

-

The bluestones (some of which are made of dolerite, an igneous rock), were thought for much of the 20th century to have been transported by humans from the Preseli Hills, 250 kilometres (160 mi) away in modern day Pembrokeshire in Wales. A newer theory is that they were brought from glacial deposits much nearer the site, which had been carried down from the northern side of the Preselis to southern England by the Irish Sea Glacier.

Other standing stones may well have been small sarsens, used later as lintels. The stones, which weighed about four tons, consisted mostly of spotted Ordovician dolerite but included examples of rhyolite, tuff and volcanic and calcareous ash; in total around 20 different rock types are represented. Each monolith measures around 2 metres (6.6 ft) in height, between 1 m and 1.5 m (3.3-4.9 ft) wide and around 0.8 metres (2.6 ft) thick. What was to become known as the Altar Stone (1), is is almost certainly derived from either Carmarthenshire or the Brecon Beacons and may have stood as a single large monolith.

The north eastern entrance was also widened at this time with the result that it precisely matched the direction of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset of the period. This phase of the monument was abandoned unfinished however, the small standing stones were apparently removed and the Q and R holes purposefully backfilled. Even so, the monument appears to have eclipsed the site at Avebury in importance towards the end of this phase. The Heelstone (5), a Tertiary sandstone, may also have been erected outside the north eastern entrance during this period although it cannot be securely dated and may have been installed at any time in phase 3.

At first, a second stone, now no longer visible, joined it. Two, or possibly three, large portal stones were set up just inside the north eastern entrance of which only one, the fallen Slaughter Stone (4), 4.9 metres (16 ft) long, now remains. Other features loosely dated to phase 3 include the four Station Stones (6), two of which stood atop mounds (2 and 3). The mounds are known as 'barrows' although they do not contain burials. The Avenue, (10), a parallel pair of ditches and banks leading 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to the River Avon was also added. Two ditches similar to Heelstone Ditch circling the Heelstone, which was by then reduced to a single monolith, were later dug around the Station Stones.

Stonehenge 3 II (2600 BC to 2400 BC)

The next major phase of activity saw 30 enormous Oligocene-Miocene sarsen stones (shown grey on the plan) brought to the site. They may have come from a quarry around 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of Stonehenge, on the Marlborough Downs, or they may have been collected from a "litter" of sarsens on the chalk downs, closer to hand. The stones were dressed and fashioned with mortise and tenon joints before 30 were erected as a 33 metres (110 ft) diameter circle of standing stones, with a ring of 30 lintel stones resting on top.

The lintels were fitted to one another using another woodworking method, the tongue and groove joint. Each standing stone was around 4.1 metres (13 ft) high, 2.1 metres (6.9 ft) wide and weighed around 25 tons. Each had clearly been worked with the final effect in mind; the orthostats widen slightly towards the top in order that their perspective remains constant as they rise up from the ground while the lintel stones curve slightly to continue the circular appearance of the earlier monument.

The sides of the stones that face inwards are smoother and more finely worked than the sides that face outwards. The average thickness of these stones is 1.1 metres (3.6 ft) and the average distance between them is 1 metre (3.3 ft). A total of 74 stones would have been needed to complete the circle and unless some of the sarsens were removed from the site, it would seem that the ring was left incomplete. Of the lintel stones, they are each around 3.2 metres (10 ft), 1 metre (3.3 ft) wide and 0.8 metres (2.6 ft) thick. The tops of the lintels are 4.9 metres (16 ft) above the ground.

Within this circle stood five trilithons of dressed sarsen stone arranged in a horseshoe shape 13.7 metres (45 ft) across with its open end facing north east. These huge stones, ten uprights and five lintels, weigh up to 50 tons each and were again linked using complex jointing. They are arranged symmetrically; the smallest pair of trilithons were around 6 metres (20 ft) tall, the next pair a little higher and the largest, single trilithon in the south west corner would have been 7.3 metres (24 ft) tall. Only one upright from the Great Trilithon still stands; 6.7 metres (22 ft) is visible and a further 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) is below ground.

The images of a 'dagger' and 14 'axe-heads' have been recorded carved on one of the sarsens, known as stone 53. Further axe-head carvings have been seen on the outer faces of stones known as numbers 3, 4, and 5. They are difficult to date but are morphologically similar to later Bronze Age weapons; recent laser scanning work on the carvings supports this interpretation. The pair of trilithons in north east are smallest, measuring around 6 metres (20 ft) in height and the largest is the trilithon in the south west of the horseshoe is almost 7.5 metres (25 ft) tall. This ambitious phase is radiocarbon dated to between 2600 and 2400 BC[8]. This is slightly before two sets of burials discovered 3 miles (4.8 km) to the west in Amesbury (the Amesbury Archer found in 2002, and the Boscombe Bowmen discovered in 2003) as well as the Stonehenge Archer whose body was discovered in the outer ditch of the monument in 1978.

At a similar time a large timber circle and another avenue were constructed overlooking the River Avon 2 miles away at Durrington Walls. Opposing the solar alignments at Stonehenge, the circle was orientated towards the rising sun on the midwinter solstice, whilst the Avenue led from the river to the circle on an alignment to the setting sun on the summer solstice. Evidence of huge fires on the banks of the Avon between the two avenues also suggests that both circles were linked, and perhaps formed a procession route used on the longest and shortest days of the year. Parker Pearson speculates that the wooden circle at Durrington Walls was the centre of a 'land of the living', whilst the stone circle represented a 'land of the dead'. The Avon would have served as a journey between the two.

Stonehenge 3 III

Later in the Bronze Age, the bluestones appear to have been re-erected for the first time, although the exact details of this period are still unclear. They were placed within the outer sarsen circle and at this time may have been trimmed in some way. A few have timber working-style cuts in them like the sarsens themselves, suggesting they may have been linked with lintels and part of a larger structure during this phase.

Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

This phase saw further rearrangement of the bluestones as they were placed in a circle between the two settings of sarsens and in an oval in the very centre. Some archaeologists argue that some of the bluestones in this period were part of a second group brought from Wales. All the stones were well-spaced uprights without any of the linking lintels inferred in Stonehenge 3 III. The Altar Stone may have been moved within the oval and stood vertically. Although this would seem the most impressive phase of work, Stonehenge 3 IV was rather shabbily built compared to its immediate predecessors, as the newly re-installed bluestones were not at all well founded and began to fall over. However, only minor changes were made after this phase. Stonehenge 3 IV dates from 2280 to 1930 BC.

Stonehenge 3 V (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

Soon afterwards, the north eastern section of the Phase 3 IV Bluestone circle was removed, creating a horseshoe-shaped setting termed the Bluestone Horseshoe. This mirrored the shape of the central sarsen Trilithons and dates from 2270 to 1930 BC. This phase is contemporary with the famous Seahenge site in Norfolk.

After the monument (1600 BC on)

The last known construction at Stonehenge was about 1600 BC (see 'Y and Z Holes' below), and the last known usage of it was likely during the Iron Age. Roman coins and medieval artefacts have all been found in or around the monument but it is unknown if the monument was in continuous use throughout prehistory and beyond - or exactly how it would have been used. Notable is the late 7th-6th century BC large arcing Scroll Trench which deepens E-NE towards Heelstone, and the construction of the massive Iron Age hillfort Vespasian's Camp built alongside the Avenue near the Avon. The burial of a decapitated 7th century Saxon man was excavated from Stonehenge. The site was known by scholars during the Middle Ages and since then it has been studied and adopted by numerous different groups.

16th to 20th centuries

Stonehenge has changed ownership on several occasions since King Henry VIII acquired Amesbury Abbey and its surrounding lands. In 1540 he gave the estate to the Earl of Hertford, and it subsequently passed to Lord Carleton and then the Marquis of Queensbury. The Antrobus family of Cheshire bought the estate in 1824, but sold it in 1915 after the last heir was killed serving in France during the First World War. The auction was held by Knight Frank & Rutley estate agents in Salisbury on the 21 September, and included "Lot 15. Stonehenge with about 30 acres, 2 rods, 37 perches of adjoining downland." Cecil Chubb bought Stonehenge for 6,600 pds. and then gave it to the nation three years later. Although it has been speculated that he purchased it at the suggestion of - or even as a present for - his wife, he in fact bought it on a whim as he believed a local man should be the new owner.

1920s onwards

In the late 1920s a nation-wide appeal was launched to save Stonehenge from the encroachment of modern buildings that had begun to appear around it. During World War I an aerodrome had been built on the down just west of the circle, and in the dry valley at Stonehenge Bottom a main road junction had appeared, with several cottages and a cafe. In 1928 the land around the stones was purchased with the appeal donations, and given to the National Trust in order to preserve it. The buildings were removed (although the roads were not), and the land returned to agriculture. More recently the land has been part of a grassland reversion scheme, returning the surrounding fields to native chalk grassland.

In 2002 a public poll voted Stonehenge as one of the seven wonders of Britain, alongside Big Ben, the Eden Project, Hadrian's Wall, the London Eye, Windsor Castle, and York Minster.

As motorised traffic increased the setting of the monument began to be affected by the proximity of the two roads on either side of it - the A344 to Shrewton on the north side, and the A303 to Winterbourne Stoke to the south. Plans to upgrade the A303 and remove it from the view of the stones have been considered since it became a World Heritage Site, but the controversy surrounding expensive re-routings of a road have led to the scheme being cancelled on multiple occasions. On 06 December 2007 it was announced that the most recent plans had been cancelled.

Neopaganism

Stonehenge is a place of pilgrimage for neo-druids, and for certain others following pagan or neo-pagan beliefs. The midsummer sunrise began attracting modern visitors in the 1870s, with the first record of recreated Druidic practices dating to 1905 when the Ancient Order of Druids enacted a ceremony. Despite efforts by archaeologists and historians to stress the differences between the Iron Age Druidic religion and the much older monument, Stonehenge has become increasingly, almost inextricably, associated with British Druidism, Neopaganism and New Age philosophy. Between 1972 and 1984, Stonehenge was the site of a free festival. After the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985 this use of the site was stopped for several years, and currently ritual use of Stonehenge is carefully controlled.

Access

When Stonehenge became open to the public it was possible to walk amongst and even climb on the stones. However this ended in 1977 when the stones were roped off as a result of serious erosion. Visitors are no longer permitted to touch the stones, but merely walk around the monument from a short distance. English Heritage does however permit access during the summer and winter solstice, and the spring and autumn equinox. Additionally, visitors can make special bookings to access the stones throughout the year.

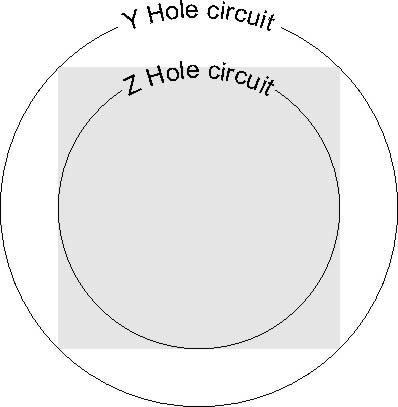

The Y and Z Holes are two rings of concentric (though irregular) circuits of near identical pits cut around the outside of the Sarsen Circle at Stonehenge. The current view is that both circuits are contemporary. Radiocarbon dating of antlers deliberately placed in Y Hole 30 provided a date of around 1600 BC, a slightly earlier date was determined for material retrieved from Z 29. These dates make the Y and Z holes the last known structural activity at Stonehenge.

The holes were discovered in 1923 by William Hawley, who, on removing the topsoil over a wide area noted them as clearly visible patches of ‘humus' against the chalk substrate.[2] Hawley named them the Y and Z because he had earlier, for a short time, labeled the then recently discovered Aubrey Holes the ‘X' holes. 18 of the Y Holes have been excavated and 16 of the Z Holes. Further evidence of the Y and Z Holes being late in the sequence of events at Stonehenge is demonstrated by the fact that hole Z 7 was found to cut into the backfill of the construction ramp for stone 7 of the Sarsen Circle.

The outer Y ring consists of 30 holes averaging 1.7m x 1.14m tapering to a flat base typically close to 1m x 0.5m, the inner Z holes, of which only 29 are known (the missing hole may lie beneath the fallen sarsen stone 8), are slightly larger, on average by some 0.1m. They can be best described morphologically as ‘wedge-shaped'. The diameter of the Y circuit, i.e. the best - fit circle is some 54m, that of the Z Hole series, around 39m.

The fills of the holes was found to be largely stone free, these deposits are thought to be the result of the gradual accumulation of wind-blown material. Examples of almost every material, both natural and artifactual, that have been found elsewhere at Stonehenge have been retrieved from their fills; this includes pottery of later periods (Iron Age, Romano-British and Medieval) also coins, horseshoe nails, and even human remains.

A new landscape investigation of the Stonehenge site was conducted in April 2009 and a shallow bank, little more than 10 cm (4 inches) high, was identified between the two hole circles. A further bank lies inside the "Z" circle. These are interpreted as the spread of spoil from the original holes, or more speculatively as hedge banks from vegetation deliberately planted to screen the activities within.

Neither Hawley, nor Richard Atkinson who investigated two of the holes (Y and Z Holes 16) in 1953 thought that uprights of timber or stone had ever been present. Atkinson however suggested that they had been intended to house bluestones, the question remains unresolved. Although unique in many ways a similarity of form between these holes and the contemporary grave pits under the Bronze Age Barrow mounds has been pointed out.

Attempts at interpreting the methods of construction used in building the stone monument sometimes show the Y and Z Holes used to locate temporary scaffold–like timber structures or 'A' frames. The fact that the stonework has been shown to be around 700 or 800 years earlier than the Y and Z Holes clearly precludes the possibility that the holes represent features cut for constructional purposes. For the same reason the Y and Z Holes cannot be logically introduced into any scheme that suggests they performed a structural function within the design of the stone monument.

Some interpretations introduce the idea that the holes were deliberately laid out in a 'spiral' pattern. However their irregular pattern still retains an integrity that can be explained as reciprocal errors created by prehistoric surveyors using a cord (equal to the radius of each circuit) passed around the stone monument (the presence of the stones would have prevented an accurate circle from being scribed from the geometric centre of the site). The distances between the two circuits appears to have been established by the geometry of simple square and circle relationships (i.e. the Z circuit is contained within a square inscribed within the Y circuit).

Throughout recorded history Stonehenge and its surrounding monuments have attracted attention from antiquarians and archaeologists. John Aubrey was one of the first to examine the site with a scientific eye in 1666, and recorded in his plan of the monument the pits that now bear his name. William Stukeley continued Aubrey's work in the early 18th century, but took an interest in the surrounding monuments as well, identifying (somewhat incorrectly) the Cursus and the Avenue. He also began the excavation of many of the barrows in the area, and it was his interpretation of the landscape that associated it with the Druids. Stukeley was in fact so fascinated with Druids that he originally named Disc Barrows as Druids Barrows. The most accurate early plan of Stonehenge was that made by Bath architect John Wood in 1740. His original annotated survey has recently been computer redrawn and published. Importantly Wood's plan was made before the collapse of the southwest Trilithon (which fell in 1797; restored 1958).

William Cunnington was the next to tackle the area in the early 19th century, excavating some 24 barrows before digging in and around the stones, discovering charred wood, animal bones, pottery and urns. He also identified the hole in which the Slaughter Stone once stood. At the same time Richard Colt Hoare began his activities, excavating some 379 barrows on Salisbury Plain before working with Cunnington and William Coxe on some 200 in the area around the Stones. To alert future diggers to their work they were careful to leave initialled metal tokens in each barrow they opened.

In 1877 Charles Darwin dabbled in archaeology at the stones, experimenting with the rate at which remains sink into the earth for his book The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms.

William Gowland oversaw the first major restoration of the monument in 1901 - the straightening and concrete setting of sarsen stone number 56 which was in danger of falling. Unfortunately in straightening it he also moved it about half a metre from its original position. He also took the opportunity to further excavate the monument at the same time in what was the most scientific dig to date, revealing more about the erection of the stones than the previous 100 years of work.

During the 1920 restoration William Hawley, who had excavated nearby Old Sarum, excavated the base of six stones being restored as well as the outer ditch. He also located a bottle of port in the slaughter stone socket left by Cunnington, helped to rediscover Aubrey's pits inside the bank and located the Y and Z Holes (concentric circular holes outside the Sarsen Circle). Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott and John F. S. Stone re-excavated much of Hawley's work in the 40s and 50s, and discovered the carved axes and daggers on the Sarsen Stones. Atkinson's work was instrumental in the understanding of the three major phases of the monument's construction.

In 1958 the stones were restored again, using concrete settings to re-erect three of the standing sarsens. The very last restoration was carried out in 1963 when stone 23 of the Sarsen Circle fell over and was once more re-erected, and the opportunity taken to concrete three more stones. Later archaeologists, including Christopher Chippindale of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge and Brian Edwards of the University of the West of England campaigned to give the public more knowledge of the various restorations and in 2004 English Heritage included pictures of the works in progress in its new book Stonehenge: A History in Photographs.

In 1966 and 1967, in advance of a new car park being built at the site, the area of land immediately northwest of the stones was excavated by Faith and Lance Vatcher. They discovered the Mesolithic postholes dating from between 7 and 8,000 BC, as well as a 10m length of a palisade ditch - a V cut ditch into which timber posts had been inserted that remained there until they rotted away. Subsequent aerial archaeology suggests that this ditch runs from the west to the north of Stonehenge, near the avenue.

Excavations were once again carried out in 1978 by Atkinson and John Evans during which they discovered the remains of the Stonehenge Archer from the outer ditch, and in 1979 rescue archaeology was needed alongside the Heel Stone after a cable-laying ditch was mistakenly dug on the roadside, revealing a new stone hole next to the Heel Stone.

In the early 1980's Julian Richards led the Stonehenge Environs Project, a detailed study of the surrounding landscape. The project was able to successfully date such features as the Lesser Cursus, Coneybury henge and several other smaller features.

More recent excavations include Mike Parker Pearson's Stonehenge Riverside Project - an series of digs held between 2003 and 2008. This project mainly investigated other monuments in the landscape and their relationship with the stones - notably Durrington Walls where another Avenue leading to the river Avon was discovered.

In April 2008 Professor Tim Darvill of the University of Bournemouth and Professor Geoff Wainwright of the Society of Antiquaries began another dig inside the Stone circle to retrieve dateable fragments of the original bluestone pillars. They were able to date the erection of some bluestones to 2300BC, although this may not reflect the earliest erection of stones at Stonehenge. They also discovered organic material from 7000 B.C., which, along with the Mesolithic postholes, adds support for the site having been in use at least 4000 years before Stonehenge was started.

In August and September 2008, as part of the Riverside Project Julian Richards and Mike Pitts excavated Aubrey Hole 7, removing the cremated remains from several Aubrey Holes that had been excavated by Hawley in the 1920s, and re-interred in 1935.

A new landscape investigation was conducted in April 2009. A shallow mound, rising to about 40 cm (16 inches) was identified between stones 54 (inner circle) and 10 (outer circle), clearly separated from the natural slope. It has not been dated but speculation that it represents careless backfilling following earlier excavations seems disproved by its representation in 18th- and 19th-century illustrations. Indeed, there is some evidence that, as an uncommon geological feature, it could have been deliberately incorporated into the monument at the outset. A circular, shallow bank, little more than 10 cm (4 inches) high, was found between the Y and Z hole circles, with a further bank lying inside the "Z" circle. These are interpreted as the spread of spoil from the original Y and Z holes, or more speculatively as hedge banks from vegetation deliberately planted to screen the activities within.

In July 2010, the Stonehenge New Landscapes Project discovered what appears to be a new henge less than 1 km (0.62 miles) away from the main site.

On 26 November 2011, archaeologists from University of Birmingham announced the discovery of evidence of two huge pits positioned within the Stonehenge Cursus pathway, aligned in celestial position towards midsummer sunrise and sunset when viewed from the Heel Stone. The new discovery is part of the Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project which began in the summer of 2010. The project uses non-invasive geophysical imaging technique to reveal and visually recreate the landscape. According to the team leader Professor Vince Gaffney, this discovery may provide a direct link between the rituals and astronomical events to activities within the Cursus at Stonehenge.

On 18 December 2011, geologists from University of Leicester and the National Museum of Wales announced the discovery of the exact source of the rock used to create Stonehenge's first stone circle. The researchers have identified the source as a 70-metre (230 ft) long rock outcrop called Craig Rhos-y-Felin near Pont Saeson in north Pembrokeshire, located 220 kilometres (140 mi) from Stonehenge.

Merlin

Stonehenge is also mentioned within Arthurian legend. Geoffrey of Monmouth said that Merlin the wizard directed its removal from Ireland, where it had been constructed on Mount Killaraus by Giants, who brought the stones from Africa. After it had been rebuilt near Amesbury, Geoffrey further narrates how first Ambrosius Aurelianus, then Uther Pendragon, and finally Constantine III, were buried inside the ring of stones. In many places in his Historia Regum Britanniae Geoffrey mixes British legend and his own imagination; it is intriguing that he connects Ambrosius Aurelianus with this prehistoric monument, seeing how there is place-name evidence to connect Ambrosius with nearby Amesbury.

According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, the rocks of Stonehenge were healing rocks which Giants brought from Africa to Ireland for their healing properties. These rocks were called The Giant's Dance. Aurelius Ambrosias (5th century), wishing to erect a memorial to the nobles (3000) who had died in battle with the Saxons and were buried at Salisbury, chose (at Merlin's advice) Stonehenge to be their monument. So the King sent Merlin, Uther Pendragon (Arthur's father), and 15,000 knights to Ireland to retrieve the rocks. They slew 7,000 Irish. As the knights tried to move the rocks with ropes and force, they failed. Then Merlin, using "gear" and skill, easily dismantled the stones and sent them over to Britain, where Stonehenge was dedicated. Shortly after, Aurelius died and was buried within the Stonehenge monument, or "The Giants' Ring of Stonehenge".

In July 1996, a 915 feet spiral of 151 circles appeared in full view of the busy A303 road, opposite England's ancient monument Stonehenge, Wiltshire, within a 45 minute period one Sunday afternoon. A pilot, gamekeeper and security guard confirmed it had not been there before 5:30 pm - yet shortly after 6:00 pm, the massive formation was being spotted by passing tourists. Much smaller man-made designs have taken several hours to complete. This also disproves the myth that all crop circles appear by night.

Ceremonies

Is there a connection with extraterrestrials

Stonehenge's 'altar stone' originally came from Scotland and not Wales, new research shows PhysOrg - August 18, 2024

Stonehenge was constructed around 5,000 years ago, with stones forming different circles brought to the site at different times. The placement of stones allows for the sun to rise through a stone "window" during summer solstice. The ancient purpose of the altar stone - which lies flat at the heart of Stonehenge, now beneath other rocks - remains a mystery.

Origin of Stonehenge's Altar Stone Once Again a Mystery Science Alert - October 3, 2023

Among the many megaliths of Stonehenge, one large slab stands out… or, more accurately, it lies down. The Altar Stone, also known as stone number 80, is a 'recumbent' slab of stone in the inner circle of the famous Neolithic monument that would have once stood 4.9 meters (just over 16 feet) tall.

Stonehenge study upends a 100-year-old theory and suggests further discoveries to come PhysOrg - October 4, 2023

A team led by researchers at the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, UK, has discovered a secret about Stonehenge stone 80, also known as the "Altar Stone," suggesting it did not come from the same source as other stones used in the construction. Many of the smaller stones are believed to be derived from a source 140 miles away from Stonehenge, but the Altar Stone is different and may be from a quarry much further away.

Long-lost fragment of Stonehenge reveals rock grains dating to nearly 2 billion years ago Live Science - August 4, 2021

A long-lost piece of Stonehenge that was taken by a man performing restoration work on the monument has been returned after 60 years, giving scientists a chance to peer inside a pillar of the iconic monument for the first time. In 1958, Robert Phillips, a representative of the drilling company helping to restore Stonehenge, took the cylindrical core after it was drilled from one of Stonehenge's pillars - Stone 58. Later, when he emigrated to the United States, Phillips took the core with him. Because of Stonehenge's protected status, it's no longer possible to extract samples from the stones. But with the core's return in 2018, researchers had the opportunity to perform unprecedented geochemical analyses of a Stonehenge pillar, which they described in a new study.

Ancient graves and mysterious enclosure discovered at Stonehenge ahead of tunnel construction Live Science - February 11, 2021

Archaeological work ahead of the construction of a controversial road tunnel beside Stonehenge has led to the discovery of ancient graves, including one with the remains of a baby dating back more than 4,500 years; a strange earth enclosure; and prehistoric pottery, among other buried treasures.

Stonehenge enhanced sounds like voices or music for people inside the monument. Scientists created a scale model one-twelfth the size of the ancient site to study its acoustics Science News - September 1, 2020

To explore Stonehenge's sound dynamics, acoustical engineer Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the University of Salford in England, where Cox works. This room simulated the acoustic effects of the open landscape surrounding Stonehenge and compacted ground inside the monument.

Archaeologists have discovered what may be the largest prehistoric monument in the entire United Kingdom, and it's just a stone's throw away from Stonehenge Live Science - June 24, 2020

By using a combination of remote sensing and hands-on excavation work, the team found evidence for at least 20 giant holes dating to the Neolithic, about 4,500 years ago. Each hole is massive, measuring at least 32 feet (10 meters) in diameter and at least 16 feet (5 m) deep.

Scientists find huge ring of ancient shafts near Stonehenge PhysOrg - June 22, 2020

Scientists find huge ring of ancient shafts near Stonehenge. Archaeologists said Monday that they have discovered a major prehistoric monument under the earth near Stonehenge that could shed new light on the origins of the mystical stone circle in southwestern England. The shafts appear to have been dug around 4,500 years ago, and could mark the boundary of a sacred area or precinct around a circular monument known as the Durrington Walls henge.

Stonehenge: DNA reveals origin of builders BBC - April 16, 2019

The ancestors of the people who built Stonehenge traveled west across the Mediterranean before reaching Britain, a study has shown. Researchers compared DNA extracted from Neolithic human remains found across Britain with that of people alive at the same time in Europe. The Neolithic inhabitants appear to have travelled from Anatolia (modern Turkey) to Iberia before winding their way north. They reached Britain in about 4,000BC.