Sloths are medium-sized South American mammals belonging to the families Megalonychidae and Bradypodidae, part of the order Pilosa. Most scientists call these two families the Folivora suborder, while some call it Phyllophaga. Sloths are herbivores, eating very little other than leaves.

Sloths have made extraordinary adaptations to an arboreal browsing lifestyle. Leaves, their main food source, provide very little energy or nutrition and do not digest easily: sloths have very large, specialized, slow-acting stomachs with multiple compartments in which symbiotic bacteria break down the tough leaves. Sloths may also eat insects and small lizards and carrion.

As much as two-thirds of a well-fed sloth's body-weight consists of the contents of its stomach, and the digestive process can take as long as a month or more to complete. Even so, leaves provide little energy, and sloths deal with this by a range of economy measures: they have very low metabolic rates (less than half of that expected for a creature of their size), and maintain low body temperatures when active (30 to 34 degrees Celsius), and still lower temperatures when resting.

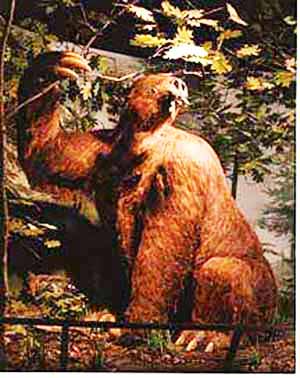

Until geologically recent times, large ground-dwelling sloths such as Megatherium lived in North America, but along with many other species they became extinct immediately after the arrival of humans on the continent.

Much evidence suggests that the extinction of the American megafauna, like that of Australia, far northern Asia, and New Zealand, resulted from human activity. However, simultaneous climate change that came with the end of the last Ice Age probably played a role as well.

10,000 years ago humans had reached the very southern tip of South America, where in present day Chilean Patagonia they shared a cavern with the giant sloth whose bones Charles Darwin discovered in the 1830's. The creatures portrayed there may have been giant sloth.

Seven thousand years later the giant sloth and most other large animal species in the Americas were extinct, but the first beginnings of complex human societies were taking shape, around 3000 BCE. Many of the large mammals (e.g., the mammoth, the saber-tooth tiger) that inhabited the Americas, some even after the end of the last ice age, became extinct, in an episode known as the late Pleistocene die off. Significant climatic change is most often cited as the reason but some anthropologists argue that the entrance of humans, first on to the North American plains east of the Canadian Rockies, then southward, could have had a dramatic impact, out of all proportions to their numbers, on the big animals at the top of the food chain. Only the small tree sloth survives today.

Early humans dined on giant sloths and other Ice Age giants, archaeologists find PhysOrg - October 2, 2025

What did early humans like to eat? The answer, according to a team of archaeologists in Argentina, is extinct megafauna, such as giant sloths and giant armadillos. In a study What did early humans like to eat? The answer, according to a team of archaeologists in Argentina, is extinct megafauna, such as giant sloths and giant armadillos. In a study published in the journal Science Advances, researchers demonstrate that these enormous animals were a staple food source for people in southern South America around 13,000 to 11,600 years ago. Their findings may also rewrite our understanding of how these massive creatures became extinct.researchers demonstrate that these enormous animals were a staple food source for people in southern South America around 13,000 to 11,600 years ago. Their findings may also rewrite our understanding of how these massive creatures became extinct.

These Giant Caves Were Not Made By Geological Processes Or Humans IFL Science - April 11, 2023

The tunnel along with many others discovered in Brazil and Argentina are thought to be made by giant sloths 8-10,000 years ago. These creatures are not like the sloths of today, with the primary difference being they were around the size of an African elephant. In the Rio Grande do Sul area, Frank and his team found over 1,500 tunnels made by the beasts, with the longest stretching for 609 meters (2,000 feet) and standing at 1.8 meters (6 feet) tall. It was likely carved out by teams of sloths over several generations. Despite their size, there is evidence that humans may have hunted giant sloths. Two hundred fossilized footprints of sloths and humans found in Utah were analyzed by a team in a 2018 study, finding them to be evidence that humans actively stalked and/or harassed sloths, if not hunted them.

Ancient sloths liked meat and two veg! Giant 10ft-long creature that lived in South America 1.8 million years ago was an omnivore, unlike its strictly plant-eating relatives Daily Mail - October 7, 2021

An extinct ground sloth that lived in South America up to 1.8 million years ago was not a strict vegetarian like most of its living relatives because it likely ate meat, a study has found. Researchers said the gigantic 10ft-long creature was an omnivore that at times consumed meat as well as plants. It had long been thought that Mylodon darwinii, also known as 'Darwin's ground sloth', was a herbivore because the majority of living sloths only eat leaves, fruit and twigs, although some occasionally snack on an insect or bird eggs.

Ancient extinct sloth tooth in Belize tells story of creature's last year PhysOrg - February 27, 2019

Some 27,000 years ago in central Belize, a giant sloth was thirsty.

Incredible Fossilized Footprints Suggest That Early Humans Stalked Giant Sloths Live Science - April 25, 2018

A bigfoot-like ground sloth had unwelcome company about 11,000 years ago. No matter which way the giant creature went, ancient humans followed it, stepping in its elongated, kidney-shaped paw prints as they tracked the furry beast, a new study suggests. Finally, it seems that the giant ground sloth couldn't take it anymore. It reared up on its hind legs - likely standing as tall as 7 feet (2.1 meters) - and swung its sharp, sickle-shaped claws around, looking at the unwanted human interlopers, according to an analysis of the fossilized foot, paw and claw marks left at the site. What happened next remains a mystery. It's possible the humans attempted to kill the sloth and may have succeeded,

Ancient species of giant sloth discovered in Mexico PhysOrg - August 18, 2017

The Pleistocene-era remains were found in 2010, but were so deep inside the water-filled sinkhole that researchers were only gradually able to piece together what they were. Scientists have so far hauled up the skull, jawbone, and a mixed bag of vertebrae, ribs claws and other bones, but the rest of the skeleton remains some 50 meters (165 feet) under water. Researchers are planning to bring up the rest by next year to continue studying the find - including to estimate how big the animal was.

LA train tunnel diggers find fossilized hip bone of giant 1,500 pound sloth that roamed the area 11,000 years ago Daily Mail - June 3, 2017

Crews digging a tunnel for a new Los Angeles train line have found the remains of an ancient giant sloth. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority says a fossilized hip joint was discovered on May 16 in a layer of sandy clay 16 feet below a major thoroughfare where the new rail line is being built. The bone is from a Harlan's ground sloth, a mammal that roamed the Los Angeles basin 11,000 years ago.

Ancient giant sloth bones suggest humans were in Americas far earlier than thought PhysOrg - November 20, 2013

A team of Uruguayan researchers working in Uruguay has found evidence in ancient sloth bones that suggests humans were in the area as far back as 30,000 years ago. Most scientists today believe that humans populated the Americas approximately 16,000 years ago, and did so by walking across the Bering Strait, which would have been frozen over during that time period. More recent evidence has begun to suggest that humans were living in South America far earlier than that - just last month a team of excavators in Brazil discovered cave paintings and ceramics that have been dated to 30,000 years ago and now, in this new effort, the research team has found more evidence of people living in Uruguay around the same time.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS