Slavery in ancient Rome differed from its modern forms in that it was not based on race. But like modern slavery, it was an abusive and degrading institution. Cruelty was commonplace. In hard times, it was not uncommon for desperate Roman citizens to raise money by selling their children into slavery.

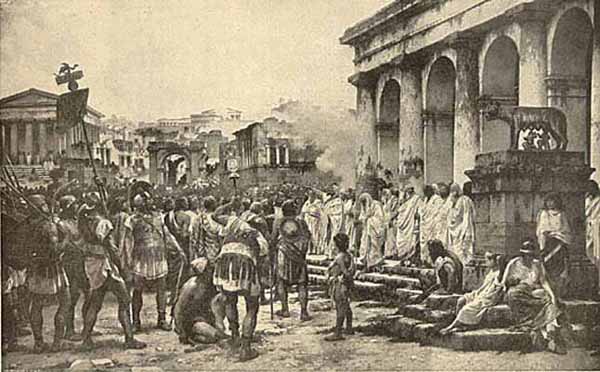

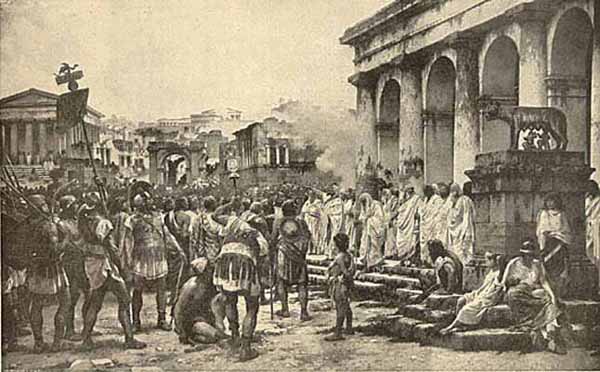

When the Romans conquered the Mediterranean, they took millions of slaves to Italy, where they toiled on the large plantations or in the houses and workplaces of wealthy citizens. The Italian economy depended on abundant slave labor, with slaves constituting 40 percent of the population. Enslaved people with talent, skill, or beauty commanded the highest prices, and many served as singers, scribes, jewelers, bartenders, and even doctors. One slave trained in medicine was worth the price of 50 agricultural slaves.

Roman law was inconsistent on slavery. Slaves were considered property; they had no rights and were subject to their owners' whims. However, they had legal standing as witnesses in courtroom proceedings, and they could eventually gain freedom and citizenship. Masters often freed loyal slaves in gratitude for their faithful service, but slaves could also save money to purchase their freedom. Conditions for slaves in Rome gradually improved, although slaves were treated cruelly in the countryside.

Some harsh masters believed in the old proverb "Every slave is an enemy," so that while humane legislation prohibited the mutilation or murder of slaves, outrageous cruelty continued. Like the Stoic philosophers, Christians taught the brotherhood of humanity and urged kindness towards slaves, but they did not consider slaves equals in status.

For example, Saint Augustine opposed the principle of slavery, but did not see how the practice could be abolished without endangering the social order. Thus he regarded it as another necessary evil resulting from humanity's fall from divine grace. Other bishops were less troubled, and the early Christian church actually acquired its own slaves.

Slavery in the Roman Empire did not suddenly end, but it was slowly replaced when new economic forces introduced other forms of cheap labor. During the late empire, Roman farmers and traders were reluctant to pay large amounts of money for slaves because they did not wish to invest in a declining economy. The legal status of "slave" continued for centuries, but slaves were gradually replaced by wage laborers in the towns and by land-bound peasants (later called serfs) in the countryside. These types of workers provided cheap labor without the initial cost that slave owners had to pay for slaves. Slavery did not disappear in Rome because of human reform or religious principle, but because the Romans found another, perhaps even harsher, system of labor.

All slaves and their families were the property of their owners, who could sell or rent them out at any time. Their lives were harsh. Slaves were often whipped, branded or cruelly mistreated. Their owners could also kill them for any reason, and would face no punishment. Although Romans accepted slavery as the norm, some people.

Slaves worked everywhere - in private households, in mines and factories, and on farms. They also worked for city governments on engineering projects such as roads, aqueducts and buildings. As a result, they merged easily into the population. In fact, slaves looked so similar to Roman citizens that the Senate once considered a plan to make them wear special clothing so that they could be identified at a glance. The idea was rejected because the Senate feared that, if slaves saw how many of them were working in Rome, they might be tempted to join forces and rebel.

Another difference between Roman slavery and its more modern variety was Manumission - the ability of slaves to be freed. Roman owners freed their slaves in considerable numbers: some freed them outright, while others allowed them to buy their own freedom. The prospect of possible freedom through manumission encouraged most slaves to be obedient and hard working. Formal manumission was performed by a magistrate and gave freed men full Roman citizenship. The one exception was that they were not allowed to hold office. However, the law gave any children born to freedmen, after formal manumission, full rights of citizenship, including the right to hold office. Informal manumission gave fewer rights. Slaves freed informally did not become citizens and any property or wealth they accumulated reverted to their former owners when they died.

Once freed, former slaves could work in the same jobs as plebeians - as craftsmen, midwives or traders. Some even became wealthy. However, Rome's rigid society attached importance to social status and even successful freedmen usually found the stigma of slavery hard to overcome - the degradation lasted well beyond the slavery itself.

The Roman writer Seneca believed that masters should treat their slaves well as a well treated slave would work better for a good master rather than just doing enough begrudgingly for someone who treated their slaves badly. Seneca did not believe that masters and their families should expect their slaves to watch them eat at a banquet when many had only had access to poor food.