Tradition held that the Senate was first established by Romulus, the mythical founder of Rome, as an advisory council consisting of the 100 heads of families, called patres ("fathers"). Later, at the start of the Republic, Lucius Junius Brutus increased the number of Senators to 300 (according to legend). They were also called conscripti ("conscripted men"), because Brutus had conscripted them. From then on, the members of the Senate were addressed as patres et conscripti, which was gradually ran together as patres conscripti ("conscript fathers").

The Roman Senate, as a political institution, was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being founded in the first days of the city (traditionally founded in 753 BC). It survived the overthrow of the kings in 509 BC, the fall of the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC, the split of the Roman Empire in 395 AD, the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 410 AD, and barbarian rule of rome in 5,6,7th centuries. The Senate of the West Roman Empire continued to function until 603 AD.

During the early Republic, the Senate was politically weak, while the executive magistrates were quite powerful. Since the transition from monarchy to constitutional rule was probably gradual, it took several generations before the Senate was able to assert itself over the executive magistrates. By the middle Republic, the Senate reached the apex of its republican power. The late Republic saw a rise in the Senate's power, which began following the reforms of the tribunes Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus.

After the transition of the Republic into the Principate, the Senate lost much of its political power as well as its prestige. Following the constitutional reforms of the Emperor Diocletian, the Senate became politically irrelevant, and never regained the power that it had once held. When the seat of government was transferred out of Rome, the Senate was reduced to a municipal body. This image was reinforced when the emperor Constantius II created an additional senate in Constantinople.

After the Western Roman Empire fell in 476, the Senate in the west functioned for a time under barbarian rule before being restored after reconquest of much of the Western Roman Empire's territories during the reign of Justinian I, until it ultimately disappeared. However, the Eastern Senate survived in Constantinople, before the ancient institution finally vanished there too.

The Roman population was divided into two classes: the Senate and the People (as seen in the famous abbreviation for "Senatus Populusque Romanus", SPQR). The People consisted of all Roman citizens who were not members of the Senate. Domestic power was vested in the Roman People, through the Centuriate Assembly (Comitia Centuriata), the Tribal Assembly (Comitia Tributa) and the Plebeian Council (Concilium Plebis). The two Assemblies and Council passed new laws and elected Rome's magistrates. The Senate's curule magistrates or the Tribunes of the Plebs (only in the Plebeian Council) could proposed new legislation to the Assemblies and the Plebeian Council, which then voted on it without debate.

The Senate held considerable authority (auctoritas) in Roman politics. It was the official body that sent and received ambassadors, and it appointed officials to manage public lands, including the provincial governors. It conducted wars and it also appropriated all public funds and issued money. It was the Senate that authorized the city's chief magistrates, the consuls, to nominate a dictator in a state of emergency. Despite its wide fiscal and judicial powers, the Senate had no executive or legislative powers (until the middle of the 2nd century A.D.). All its propositions (Senatus Consultum - S.C.) were subject to ratification by the peoples assembly.

However, due to its enormous prestige and the fact that all the elected officials were in fact Senators, most of Senatus Consultum were enacted. One historical rejection occurred, however, just after the the end of the Hannibalic war. The Senate felt that a strong Macedonian kingdom could be a potential threat. The people however, tired by the long and exhausting war against Hannibal and Carthage rejected the Senate's motion.

It must be noted that the Roman assemblies of the People, could not debate on the motions brought up before them. They either accepted them or rejected them. A usual practice of magistrates was to bring before the Senate all laws (leges) before calling the assemblies to vote. The Senate gave its auctoritas before the people could vote on the motion of the magistrate. This practice was by the middle Republic a formality, which was however practiced by all magistrates. In the late Republic, the Senate chose to avoid setting up dictatorships by resorting to the so-called senatus consultum ultimum, which declared martial law and empowered the consuls to "take care that the Republic should come to no harm".

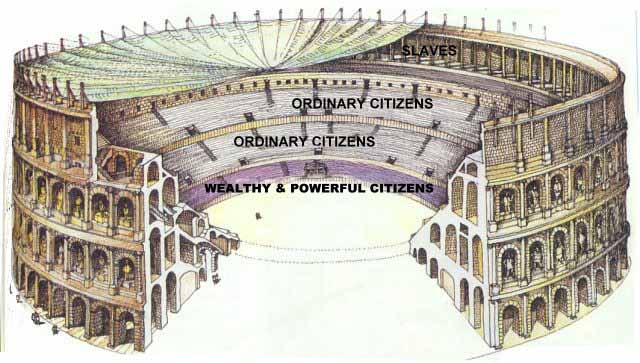

Like the Comitia Centuriata and the Comitia Tributa, but unlike the Concilium Plebis, the Senate operated under certain religious restrictions. It could only meet in a consecrated temple, which was usually the Curia Hostilia, although the ceremonies of New Year's Day were in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus and war meetings were held in the temple of Bellona. Its sessions could only proceed after an invocation prayer, a sacrificial offering and the auspices were made. The Senate could only meet between sunrise and sunset, and could not meet while any of the assemblies were in session.

The Senate had around 600 members in the middle and late Republic. Customarily, all popularly elected magistrates - quaestors, aediles (both curulis and plebis), praetors, and consuls - were admitted to the Senate, though the inclusion of tribunes in the senate varied historically. A Roman nobleman who possessed the appropriate financial and property qualifications could also be inducted into the Senate by the Censors. Senators who had not been elected as magistrates higher than quaestors were called senatores pedarii and were not permitted to speak. Their number was increased dramatically by Sulla, and around half (49.5%) of the pedarii from 78-49 BC were homines novi ("new men"), that is, those whose families had never attained higher magistracy. Outside the pedarii, the number of homines novi was lower, with about 33% of tribunes, 29% of aediles, 22% of praetors, and only 1% of consuls being true novi.

A Senator's membership was for his lifetime, barring certain indiscretions. Senators could not participate directly in business, trade, or usury, however many found ways to discreetly circumvent these restrictions. One of the primary functions of the Censors was to review the Senate rolls and expel members for improper practices. After Sulla's enlargement, membership in the Senate could be stripped by the Censors if a Senator had been found guilty of disregard of the mores maiorum (public morals, literally: the ways of the forefathers), e.g. corruption, disregard of a colleague's veto, abuse of capital punishment, severe domestic violence, improper treatment of "clients" or slaves, and bankrupts or adultery, or if auspices demanded to.

The Senate of the Roman Kingdom was a political institution in the ancient Roman Kingdom. The word senate derives from the Latin word senex, which means "old man"; the word thus means "assembly of elders". The prehistoric Indo-Europeans who settled Italy in the centuries before the legendary founding of Rome in 753 BC were structured into tribal communities, and these communities often included an aristocratic board of tribal elders.

The early Roman family was called a gens or "clan", and each clan was an aggregation of families under a common living male patriarch, called a pater (the Latin word for "father"). When the early Roman gentes were aggregating to form a common community, the patres from the leading clans were selected for the confederated board of elders (what would become the Roman Senate). Over time, the patres came to recognize the need for a single leader, and so they elected a king (rex), and vested in him their sovereign power. When the king died, that sovereign power naturally reverted back to the patres.

The Senate is said to have been created by Rome's first king, Romulus, initially consisting of 100 men. The descendants of those 100 men subsequently became the patrician class. Rome's fifth king, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, chose a further 100 senators. They were chosen from the minor leading families, and were accordingly called the minorum gentium.

Rome's seventh and final king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, executed many of the leading men in the senate, and did not replace them, thereby diminishing their number. However, in 509 BC Rome's first consuls, Lucius Junius Brutus and Publius Valerius Publicola chose from amongst the leading equites new men for the Senate, these being called conscripti, and thus increased the size of the senate to 300.

The senate of the Roman Kingdom held three principal responsibilities: It functioned as the ultimate repository for the executive power, it served as the council to the king, and it functioned as a legislative body in concert with the People of Rome. During the years of the monarchy, the Senate's most important function was to elect new kings. While the king was technically elected by the people, it was actually the Senate who chose each new king.

The period between the death of one king, and the election of a new king, was called the interregnum, during which time the Interrex nominated a candidate to replace the king. After the senate gave its initial approval to the nominee, he was then formally elected by the people, and then received the Senate's final approval. At least one king, Servius Tullius, was elected by the Senate alone, and not by the people.

The Senate's most significant task, outside of regal elections, was in its capacity as the king's council, and while the king could ignore any advice offered to him by the Senate, the Senate's growing prestige helped make the advice that it offered increasingly difficult to ignore. Technically the Senate could also make new laws, although it would be incorrect to view the senate's decrees as "legislation" in the modern sense. Only the king could decree new laws, although he often involved both the senate and the Curiate Assembly (the popular assembly) in the process.

After the fall of the Roman Republic, the constitutional balance of power shifted from the Roman Senate to the Roman Emperor. Though retaining its legal position as under the Republic, in practice, however the actual authority of the Imperial Senate was negligible, as the Emperor held the true power in the state. As such, membership in the Senate became sought after by individuals seeking prestige and social standing, rather than actual authority.

During the reigns of the first Emperors, legislative, judicial, and electoral powers were all transferred from the Roman assemblies to the senate. However, since the Emperor held control over the Senate, the Senate acted as a vehicle through which the Emperor exercised his autocratic powers.

The first Emperor, Augustus, reduced the size of the Senate from 900 members to 600 members, even though there were about 100 to 200 active senators at one time. After this point, the size of the Senate was never again drastically altered. Under the Empire, as was the case during the late Republic, one could become a senator by being elected Quaestor (a magistrate with financial duties), but only if one was of senatorial rank.

If an individual was not of senatorial rank, there were two ways for that individual to become a senator. Under the first method, the Emperor granted that individual the authority to stand for election to the Quaestorship, while under the second method, the emperor appointed that individual to the Senate by issuing a decree. Under the Empire, the power that the Emperor held over the Senate was absolute.

During Senate meetings, the Emperor sat between the two Consuls, and usually acted as the presiding officer. Senators of the early Empire could ask extraneous questions or request that a certain action be taken by the Senate. Higher ranking senators spoke before lower ranking senators, although the Emperor could speak at any time.

Besides the Emperor, Consuls and Praetors could also preside over the Senate. Since no senator could stand for election to a magisterial office without the Emperor's approval, senators usually did not vote against bills that had been presented by the Emperor. If a senator disapproved of a bill, he usually showed his disapproval by not attending the Senate meeting on the day that the bill was to be voted on.

While the Roman assemblies continued to meet after the founding of the Empire, their powers were all transferred to the Senate, and so senatorial decrees (senatus consulta) acquired the full force of law. The legislative powers of the Imperial Senate were principally of a financial and an administrative nature, although the senate did retain a range of powers over the provinces.

During the early Roman Empire, all judicial powers that had been held by the Roman assemblies were also transferred to the senate. For example, the Senate now held jurisdiction over criminal trials. In these cases, a Consul presided, the senators constituted the jury, and the verdict was handed down in the form of a decree (senatus consultum), and, while a verdict could not be appealed, the Emperor could pardon a convicted individual through a veto. The Emperor Tiberius transferred all electoral powers from the assemblies to the Senate, and, while theoretically the Senate elected new magistrates, the approval of the Emperor was always needed before an election could be finalized.

Around 300 AD, the emperor Diocletian enacted a series of constitutional reforms. In one such reform, Diocletian asserted the right of the Emperor to take power without the theoretical consent of the Senate, thus depriving the Senate of its status as the ultimate depository of supreme power. Diocletian's reforms also ended whatever illusion had remained that the senate had independent legislative, judicial, or electoral powers. The senate did, however, retain its legislative powers over public games in Rome, and over the senatorial order.

The Senate also retained the power to try treason cases, and to elect some magistrates, but only with the permission of the Emperor. In the final years of the Empire, the Senate would sometimes try to appoint their own emperor, such as in case of Eugenius who was later defeated by forces loyal to Theodosius I. The Senate remained the last stronghold of the traditional Roman religion in the face of the spreading Christianity, and several times attempted to facilitate the return of the Altar of Victory (first removed by Constantius II) to the senatorial curia.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Senate continued to function under the barbarian chieftain Odoacer, and then under Ostrogothic rule. The authority of the Senate rose considerably under barbarian leaders, who sought to protect the Senate. This period was characterized by the rise of prominent Roman senatorial families, such as the Anicii, while the Senate's leader, the princeps senatus, often served as the right hand of the barbarian leader. It is known that the Senate succeeded to install Laurentius as pope in 498, despite the fact that both king Theodoric and Emperor Anastasius supported the other pretender, Symmachus.

The peaceful co-existence of senatorial and barbarian rule continued until the Ostrogothic leader Theodahad began an uprising against Emperor Justinian I and took the senators as hostages. Several senators were executed in 552 as a revenge for the death of the Ostrogothic king Totila. After Rome was recaptured by the Imperial (Byzantine) army, the Senate was restored, but the institution (like classical Rome itself) had been mortally weakened by the long war. Many senators had been killed and many of those who had fled to the East chose to remain there, thanks to favorable legislation passed by emperor Justinian, who, however, abolished virtually all senatorial offices in Italy. The importance of the Roman Senate thus declined rapidly.

In 578 and again in 580, the Senate sent envoys to Constantinople which delivered 3000 pounds of gold as gift to the new Emperor Tiberius II Constantinus, along with a plea for help against the Lombards, who had invaded Italy ten years earlier. Pope Gregory I, in a sermon from 593 (Senatus deest, or.18), lamented the almost complete disappearance of the senatorial order and the decline of the prestigious institution.

It is not clearly known when the Roman Senate disappeared in the West, but it is known from Gregorian register that the Senate acclaimed new statues of Emperor Phocas and Empress Leontia in 603. The institution must have vanished by 630 when the Curia was transformed into a church by Pope Honorius I.

In later medieval times, the title "Senator" was still in occasional use, but it had become a meaningless adjunct title of nobility and no longer implied membership of an organized governing body.

In 1144 the Commune of Rome attempted to establish a government modeled on the old Roman Republic in opposition to the temporal power of the higher nobles and the popes. This included setting up a senate on the lines of the ancient one. The revolutionaries divided Rome into fourteen regions, each electing four senators for a total of 56 (though one source, often repeated, gives a total of 50). These senators, the first real senators since the 7th century, elected as their leader Giordano Pierleoni, son of the Roman consul Pier Leoni with the title patrician, because consul was also a deprecated noble styling.

This new-old form of government was constantly embattled. By the end of the 12th Century it underwent a radical transformation, with the reduction of the number of senators to a single one - Summus Senator being thereafter the title of the head of the civil government of Rome. Between 1191 to 1193, this was a certain Benedetto called Carus homo or carissimo.

The Senate continued to exist in Constantinople, however. In the second half of the 10th century a new office, proedrus was created as a head of the Senate by Emperor Nicephorus Phocas. Up to mid-11th century only eunuchs could become pro‘drus, but later this restriction was lifted and several proedri could be appointed, of which the senior proedrus served as the head of Senate. There were two types of meetings practised: silentium, in which participated only magistrates currently in office and conventus, where all syncletics could participate. The senate in Constantinople existed at least until the beginning of 13th century, its last known act being the election of Nicolas Canabus as Emperor in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade.