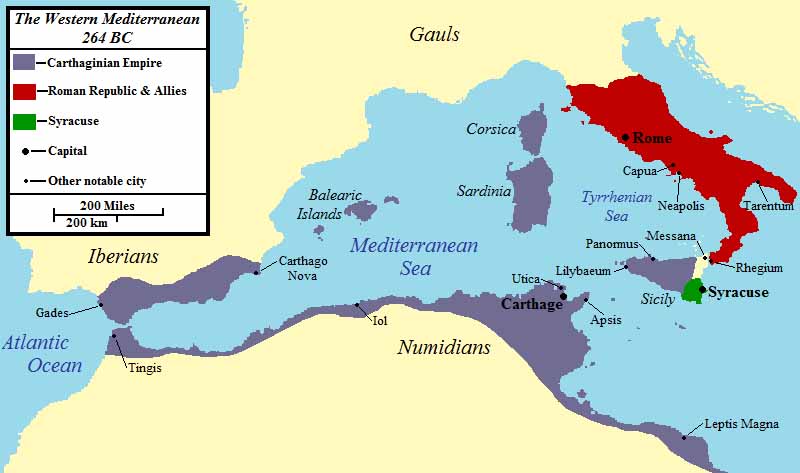

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 BC to 146 BC. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place, much like today's World Wars. The term Punic comes from the Latin word Punicus (or Poenicus), meaning "Carthaginian", with reference to the Carthaginians' Phoenician ancestry.

The main cause of the Punic Wars was the fight of interests between the existing Carthaginian Empire and the expanding Roman Republic. The Romans were initially interested in expansion via Sicily (which at that time was a cultural melting pot), part of which lay under Carthaginian control. At the start of the first Punic War, Carthage was the dominant power of the Western Mediterranean, with an extensive maritime empire, while Rome was the rapidly ascending power in Italy, but lacked the naval power of Carthage.

By the end of the third war, after more than a hundred years and the loss of many hundreds of thousands of soldiers from both sides, Rome had conquered Carthage's empire and completely destroyed the city, becoming the most powerful state of the Western Mediterranean. With the end of the Macedonian wars - which ran concurrently with the Punic Wars - and the defeat of the Seleucid King Antiochus III the Great in the Roman–Syrian War (Treaty of Apamea, 188 BC) in the eastern sea, Rome emerged as the dominant Mediterranean power and one of the most powerful cities in classical antiquity. The Roman victories over Carthage in these wars gave Rome a preeminent status it would retain until the 5th century AD.

During the mid-3rd century BC, Carthage was a large city located on the coast of modern Tunisia. Founded by the Phoenicians in the mid-9th century BC, it was a powerful thalassocratic city-state with a vast commercial network. Of the great city-states in the western Mediterranean, only Rome rivaled it in power, wealth, and population.

While Carthage's navy was the largest in the ancient world at the time, it did not maintain a large, permanent, standing army. Instead, Carthage relied mostly on mercenaries, especially the indigenous Numidian Berbers, to fight its wars. However, most of the officers who commanded the armies were Carthaginian citizens. The Carthaginians were famed for their abilities as sailors, and unlike their armies, many Carthaginians from the lower classes served in their navy, which provided them with a stable income and career.

In 200 BC the Roman Republic had gained control of the Italian peninsula south of the Po river. Unlike Carthage, Rome had large disciplined armed forces. On the other hand, at the start of the First Punic War the Romans had no navy, and were thus at a disadvantage until they began to construct their own large fleets during the war.

The First Punic War was primarily fought in Sicily and at sea. Both states suffered heavily; Rome was the victor, receiving Sicily and Sardinia as spoils. It was the first of three major wars between the two powers for supremacy in the Mediterranean Sea. After 23 years of fighting, Rome emerged the victor and imposed heavy conditions upon Carthage as the price for peace. The conflict was called the "Punic War" because Rome's name for Carthaginians was Punici (older Phoenici, due to their Phoenician ancestry).

In the middle of the 3rd century BC, the power of Rome was growing. Following centuries of internal rebellions and disturbances, the whole of the Italian peninsula was tightly secured under Roman hands. All enemies - such as the Latin league or the Samnites - had been overcome, and the invasion of Pyrrhus of Epirus was repelled.

Romans had an enormous confidence in their political system and military. Across the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Strait of Sicily, Carthage was already an established naval and commercial power, controlling most of the Mediterranean maritime trade routes. Originally a Phoenician colony, the city had become the center of a wide commercial empire reaching along the North African coast to as far as Iberia.

In 288 BC, the Mamertines, a group of Italian mercenaries, occupied the city of Messina in the northeastern tip of Sicily, killing all the men and taking the women as their wives. From this base, they ravaged the countryside and became a problem for the independent city of Syracuse. When Hiero II, tyrant of Syracuse, came to power in 265 BC, he decided to take definitive action against the Mamertines and besieged Messina.

The Mamertines then appealed for help simultaneously to Rome and Carthage. At first, the Romans did not wish to the aid of soldiers who had unjustly stolen a city from its rightful possessors. Moreover, Rome had recently dealt with an insurrection of mercenaries following the defeat of Pyrrhus of Epirus (Rhegium, 271) and was probably reluctant to help this faction now, so Carthage was the first city to respond to the plea and send troops to the area.

Most likely unwilling to see Carthaginian power spread further over Sicily and get too close to Italy, Rome responded by entering into an alliance with the Mamertines.

In 264 BC, Roman troops were deployed to Sicily (the first time a Roman army acted outside the Italian peninsula) and forced a reluctant Syracuse to join their alliance. Soon enough the only parties in the dispute were Rome and Carthage and the conflict evolved into a struggle for the possession of Sicily.

As Sicily was a hilly island, with geographical obstacles and a terrain where lines of communication are difficult to maintain, land warfare played a secondary role in the First Punic War. Land operations were mostly confined to small scale raids and skirmishes between the armies, with hardly any pitched battle. Sieges and land blockades were the most common operations for the regular army. The main targets of blockading were the important naval ports, since neither of the belligerent parties were based in Sicily and both needed a continuous supply of reinforcements and communication with the mainland.

Despite these general considerations, at least two large scale land campaigns were fought during the First Punic War. In 262 BC, Rome besieged the city of Agrigentum, an operation that involved both consular armies - a total of four Roman legions - and took several months to resolve. The garrison of Agrigentum managed to call for reinforcements and a Carthaginian relief force commanded by Hanno came to the rescue. With the supplies from Syracuse cut, the Romans found themselves also besieged and constructed a line of circumvallation. After a few skirmishes, the battle of Agrigentum was fought and won by Rome, and the city fell.Inspired by this victory, Rome attempted (256/255 BC) another large scale land operation, this time with different results.

Following several naval battles, Rome was aiming for a quick end to the war and decided to invade the Carthaginian colonies of Africa, to force the enemy to accept terms. A major fleet was built, both of transports for the army and its equipment and warships for protection. Carthage tried to intervene but was defeated in the battle of Cape Ecnomus.

As a result, the Roman army commanded by Marcus Atilius Regulus landed in Africa and started to ravage the Carthaginian countryside. At first Regulus was victorious, winning the battle of Adys and forcing Carthage to sue for peace. The terms were so heavy that negotiations failed and, in response, the Carthaginians hired Xanthippus, a Spartan mercenary, to reorganize the army. Xanthippus managed to cut off the Roman army from its base by re-establishing Carthiginian naval supremacy, then defeated and captured Regulus at the battle of Tunis.

Towards the end of the conflict (249 BC), Carthage sent general Hamilcar Barca (Hannibal's father) to Sicily. Hamilcar managed to gain control of most of inland Sicily; in desperation, the Romans appointed a dictator to resolve the situation. Nevertheless, Carthaginian success in Sicily was secondary to the progress of the war at sea; Hamilcar remaining undefeated in Sicily became irrelevant following the Roman naval victory at the battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BC.

Roman Navy

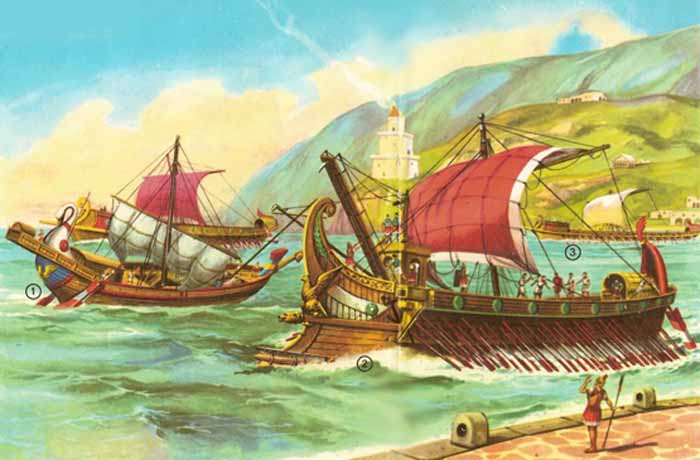

Due to the difficulty of operating in Sicily, most warfare of the First Punic War was fought at sea, including the most decisive battles. Moreover, naval warfare permitted an efficient blockade of enemy ports, and consequently of reinforcement and supply for the inland troops. Both sides of the conflict had publicly funded fleets. This fact compromised Carthage and Rome's finances and eventually decided the course of the war.

At the beginning of the First Punic War, Rome had virtually no experience in naval warfare, whereas Carthage had a great deal of experience on the seas thanks to its sea-based trade. Nevertheless, the Republic soon understood the importance of Mediterranean control in the outcome of the conflict.The first large fleet was constructed after the victory of Agrigentum in 261 BC. Since Rome lacked naval technology, the design of the warships was copied in a straightforward manner from captured Carthaginian triremes and quinqueremes.

Perhaps in order to compensate for the lack of experience, and to make use of standard land military tactics on sea, the Romans equipped their new ships with a special boarding device, the corvus. The new weapon's efficiency was first proved in the battle of Mylae, the first Roman naval victory, and continued to prove its value in the following years, especially in the huge Battle of Ecnomus. The addition of the corvus forced Carthage to review its military tactics, and since the city had difficulty in doing so, Rome had the naval advantage. Later, as Roman experience in naval warfare grew, the corvus device was abandoned due to its impact on the navigability of the war vessels.

Despite the Roman victories in sea, the Republic was the side that lost most ships and crews during the war, largely due to the effect of storms. On at least two occasions (255 and 253 BC) whole fleets were destroyed in bad weather. The weight of the corvus on the prows of the ships was largely responsible for the disasters. Towards the end of the war Carthage ruled the seas, as Rome was unwilling to finance the construction of yet another expensive fleet. The Romans did however build another fleet paid for with donations from wealthy citizens.

The First Punic War was decided in the naval battle of the Aegates Islands (March 10, 241 BC), where the new Roman fleet under consul Gaius Lutatius Catulus scored a victory. Carthage lost most of its fleet and was economically incapable of funding another, or to find manpower for the crews. With no fleet, Hamilcar Barca was cut from Carthage and forced to surrender.

Rome won the First Punic War after 23 years of conflict and in the end replaced Carthage as the dominant naval power of the Mediterranean. In the aftermath of the war, both states were financially and demographically exhausted. To determine the final borders of their territories, they drew what they considered a straight line across the Mediterranean. Hispania, Corsica, Sardinia and Africa remained Carthaginian.

All that was north of that line was signed over to Rome. Rome's victory was greatly influenced by its persistent refusal to admit defeat and by accepting only total victory. Moreover, the Republic's ability to attract private investments in the war effort by playing on their citizens' patriotism to fund ships and crews, was one of the deciding factors of the war, particularly when contrasted with the Carthaginian nobility's apparent unwillingness to risk their fortunes for the common good. The end of the First Punic War also resulted in the official birth of Roman navy, further enticing the expansion of the Roman Empire.

According to Polybius there had been several trade agreements between Rome and Carthage, even a mutual alliance against king Pyrrhus of Epirus. When Rome and Carthage made peace in 241 BC, Rome secured the release of all 8,000 prisoners of war without ransom and, furthermore, received a considerable amount of silver as a war indemnity. However, Carthage refused to deliver to Rome the Roman deserters serving among their troops. A first issue for dispute was that the initial treaty, agreed upon by Hamilcar Barca and the Roman commander in Sicily, had a clause stipulating that the Roman popular assembly had to accept the treaty in order for it to be valid. The assembly not only rejected the treaty but increased the indemnity Carthage had to pay.

Carthage had a liquidity problem and attempted to gain financial help from Egypt, a mutual ally of Rome and Carthage, but failed. This resulted in delay of payments owed to the mercenary troops that had served Carthage in Sicily, leading to a climate of mutual mistrust and, finally, a revolt supported by the Libyan natives, known as the Mercenary War (240–238 BC). During this war, Rome and Syracuse both aided Carthage, although traders from Italy seem to have done business with the insurgents. Some of them were caught and punished by Carthage, aggravating the political climate which had started to improve in recognition of the old alliance and treaties.

During the uprising in the Punic mainland, the mercenary troops in Corsica and Sardinia toppled Punic rule and briefly established their own, but were expelled by a native uprising. After securing aid from Rome, the exiled mercenaries then regained authority on the island of Sicily. For several years a brutal campaign was fought to quell the insurgent natives. Like many Sicilians, they would ultimately rise again in support of Carthage during the Second Punic War.

Eventually, Rome annexed Corsica and Sardinia by revisiting the terms of the treaty that ended the first Punic War. As Carthage was under siege and engaged in a difficult civil war, they begrudgingly accepted the loss of these islands and the subsequent Roman conditions for ongoing peace, which also increased the war indemnity levied against Carthage after the first Punic War. This eventually plunged relations between the two powers to a new low point.

After Carthage emerged victorious from the Mercenary War there were two opposing factions: the reformist party was led by Hamilcar Barca while the other, more conservative, faction was represented by Hanno the Great and the old Carthaginian aristocracy. Hamilcar had led the initial Carthaginian peace negotiations and was blamed for the clause that allowed the Roman popular assembly to increase the war indemnity and annex Corsica and Sardinia, but his superlative generalship was instrumental in enabling Carthage to ultimately quell the mercenary uprising, ironically fought against many of the same mercenary troops he had trained. Hamilcar ultimately left Carthage for the Iberian peninsula where he captured rich silver mines and subdued many tribes who fortified his army with levies of native troops.

Hanno had lost many elephants and soldiers when he became complacent after a victory in the Mercenary War. Further, when he and Hamilcar were supreme commanders of Carthage's field armies, the soldiers had supported Hamilcar when his and Hamilcar's personalities clashed. On the other hand he was responsible for the greatest territorial expansion of Carthage's hinterland during his rule as strategus and wanted to continue such expansion. However, the Numidian king of the relevant area was now a son-in-law of Hamilcar and had supported Carthage during a crucial moment in the Mercenary War. While Hamilcar was able to obtain the resources for his aim, the Numidians in the Atlas Mountains were not conquered, like Hanno suggested, but became vassals of Carthage.

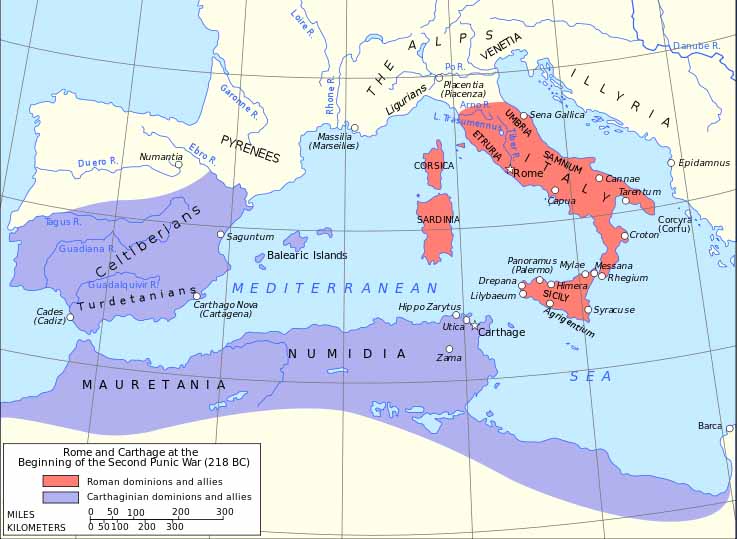

The Iberian conquest was begun by Hamilcar Barca and his other son-in-law, Hasdrubal the Fair, who ruled relatively independently of Carthage and signed the Ebro treaty with Rome. Hamilcar died in battle in 228 BC. Around this time, Hasdrubal became Carthaginian commander in Iberia (229 BC). He maintained this post for some eight years until 221 BC.

Soon the Romans became aware of a burgeoning alliance between Carthage and the Celts of the Po river valley in northern Italy. The latter were amassing forces to invade Italy, presumably with Carthaginian backing. Thus, the Romans preemptively invaded the Po region in 225 BC. By 220 BC, the Romans had annexed the area as Gallia Cisalpina.

Hasdrubal was assassinated around the same time (221 BC), bringing Hannibal to the fore. It seems that, having apparently dealt with the threat of a Gaulo-Carthaginian invasion of Italy (and perhaps with the original Carthaginian commander killed), the Romans lulled themselves into a false sense of security. Thus, Hannibal took the Romans by surprise a mere two years later (218 BC) by merely reviving and adapting the original Gaulo-Carthaginian invasion plan of his brother-in-law Hasdrubal.

After Hasdrubal's assassination by a Celtic assassin, Hamilcar's young sons took over, with Hannibal becoming the strategus of Iberia, although this decision was not undisputed in Carthage. The output of the Iberian silver mines allowed for the financing of a standing army and the payment of the war indemnity to Rome. The mines also served as a tool for political influence, creating a faction in Carthage's magistrate that was called the Barcino.

In 219 BC Hannibal attacked the town of Saguntum, which stood under the special protection of Rome. According to Roman tradition, Hannibal had been made to swear by his father never to be a friend of Rome, and he certainly did not take a conciliatory attitude when the Romans berated him for crossing the river Iberus (Ebro) which Carthage was bound by treaty not to cross. Hannibal did not cross the Ebro River (Saguntum was near modern Valencia - well south of the river) in arms, and the Saguntines provoked his attack by attacking their neighboring tribes who were Carthaginian protectorates and by massacring pro-Punic factions in their city. Rome had no legal protection pact with any tribe south of the Ebro River. Nonetheless, they asked Carthage to hand Hannibal over, and when the Carthaginian oligarchy refused, Rome declared war on Carthage.

The 'Barcid Empire' consisted of the Punic territories in Iberia. According to the historian Pedro Barcelo, it can be described as a private military-economic hegemony backed by the two independent powers, Carthage and Gades. These shared the profits of the silver mines in southern Iberia with the Barcas family and closely followed Hellenistic diplomatic customs. Gades played a supporting role in this field, but Hannibal visited the local temple to conduct ceremonies before launching his campaign against Rome. The Barcid Empire was strongly influenced by the Hellenistic kingdoms of the time and for example, contrary to Carthage, it minted silver coins in its short time of existence.

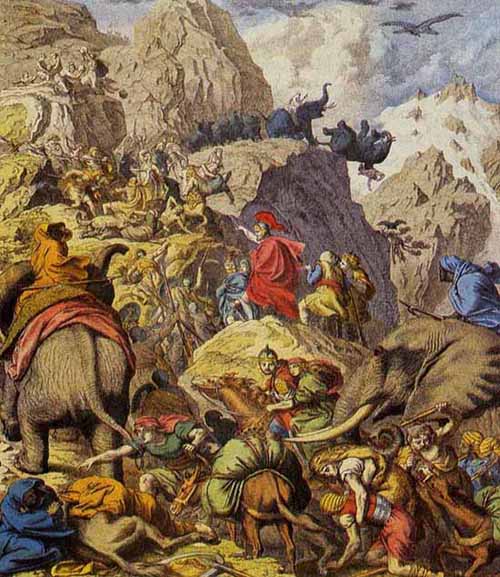

Depiction of Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps during the Second Punic War.

The Second Punic War, also referred to as The Hannibalic War, (by the Romans) The War Against Hannibal, or "The Carthaginian War", lasted from 218 to 201 BC and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean. This was the second major war between Carthage and the Roman Republic, with the crucial participation of Numidian-Berber armies and tribes on both sides. The two states had three major conflicts against each other over the course of their existence. They are called the "Punic Wars" because Rome's name for Carthaginians was Punici, due to their Phoenician ancestry.

The war is marked by Hannibal's surprising overland journey and his costly crossing of the Alps, followed by his reinforcement by Gaulish allies and crushing victories over Roman armies in the battle of the Trebia and the giant ambush at Trasimene. Against his skill on the battlefield the Romans deployed the Fabian strategy. But because of the increasing unpopularity of this approach, the Romans resorted to a further major field battle. The result was the Roman defeat at Cannae.

In consequence many Roman allies went over to Carthage, prolonging the war in Italy for over a decade, during which more Roman armies were destroyed on the battlefield. Despite these setbacks, the Roman forces were more capable in siegecraft than the Carthaginians and recaptured all the major cities that had joined the enemy, as well as defeating a Carthaginian attempt to reinforce Hannibal at the battle of the Metaurus.

In the meantime in Iberia, which served as the main source of manpower for the Carthaginian army, a second Roman expedition under Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major took New Carthage by assault and ended Carthaginian rule over Iberia in the battle of Ilipa. The final showdown was the battle of Zama in Africa between Scipio Africanus and Hannibal, resulting in the latter's defeat and the imposition of harsh peace conditions on Carthage, which ceased to be a major power and became a Roman client-state.

All battles mentioned in the introduction are ranked among the most costly traditional battles of human history; in addition there were a few successful ambushes of armies that also ended in their annihilation.

After assaulting Saguntum, Hannibal surprised the Romans in 218 BC by leading the Iberians and three dozen elephants through the Alps. Although Hannibal surprised the Romans and thoroughly beat them on the battlefields of Italy, he lost his only siege engines and most of his elephants to the cold temperatures and icy mountain paths. In the end it allowed him to defeat the Romans in the field, but not in the strategically crucial city of Rome itself, thus making him unable to win the war.

Hannibal defeated the Roman legions in several major engagements, including the Battle of the Trebia, the Battle of Lake Trasimene and most famously at the Battle of Cannae, but his long-term strategy failed. Lacking siege engines and sufficient manpower to take the city of Rome itself, he had planned to turn the Italian allies against Rome and starve the city out through a siege. However, with the exception of a few of the southern city-states, the majority of the Roman allies remained loyal and continued to fight alongside Rome, despite Hannibal's near-invincible army devastating the Italian countryside. Rome also exhibited an impressive ability to draft army after army of conscripts after each crushing defeat by Hannibal, allowing them to recover from the defeats at Cannae and elsewhere and keep Hannibal cut off from aid.

More importantly, Hannibal never successfully received any significant reinforcements from Carthage. Despite his many pleas, Carthage only ever sent reinforcements successfully to Hispania. This lack of reinforcements prevented Hannibal from decisively ending the conflict by conquering Rome through force of arms.

The Roman army under Quintus Fabius Maximus intentionally deprived Hannibal of open battle, while making it difficult for Hannibal to forage for supplies. Nevertheless, Rome was also incapable of bringing the conflict in the Italian theatre to a decisive close. Not only were they contending with Hannibal in Italy, and his brother Hasdrubal in Hispania, but Rome had embroiled itself in yet another foreign war, the first of its Macedonian wars against Carthage's ally Philip V, at the same time. Hannibal used elephants for the first time in war.

Through Hannibal's inability to take strategically important Italian cities, the general loyalty Italian allies showed to Rome, and Rome's own inability to counter Hannibal as a master general, Hannibal's campaign continued in Italy inconclusively for sixteen years. Though he managed to sustain for 15 years, he did so only by ravaging farm lands, keeping his army healthy, which brought anger among the Roman's subject states. Realizing that Hannibal's army was outrunning its supply lines quickly, Rome took countermeasures against Hannibal's home base in Africa by sea command and stopped the flow of supplies. Hannibal quickly turned back and rushed to home defense, but was soundly defeated in the Battle of Zama.

In Hispania, a young Roman commander, Publius Cornelius Scipio (later to be given the agnomen Africanus because of his feats during this war), eventually defeated the larger but divided Carthaginian forces under Hasdrubal and two other Carthaginian generals. Abandoning Hispania, Hasdrubal moved to bring his mercenary army into Italy to reinforce Hannibal.

The Third Punic War was fought between Carthage and the Roman Republic from 149 BC to 146 BC. This was the last in a series of three wars.

In the years between the Second and Third Punic Wars, Rome was engaged in the conquest of the Hellenistic empires to the east and ruthlessly suppressing the Iberian people in the west, although they had been essential to the Roman success in the Second Punic War.

Carthage, stripped of allies and territory (Sicily, Hispania), was suffering under a yearly indemnity of 200 silver talents to be paid every year for 50 years, an enormous sum.

The Romans still harboured a bitter hatred for Carthage, which had nearly destroyed them in the Second Punic War. Sentiments ran so strong that the powerful statesman Cato stated during a discussion of Carthage's fate, ceterum censeo Carthaginem delendam esse. (Besides which, I think that Carthage must be destroyed).

Meanwhile, Carthage had regained much of its prosperity through trade, further alarming Rome that a revived Carthage could again threaten them with war. The peace treaty at the end of the Second Punic War required that all border disputes involving Carthage be arbitrated by the Roman Senate and required Carthage to get explicit Roman approval before arming its citizens, or hiring a mercenary force.

As a result, in the fifty intervening years between the Second and Third wars Carthage had to take all border disputes with Rome's ally Numidia to the Senate, where they were decided almost exclusively in Numidian favor.

In 151 B.C., however, when the Carthaginian debt to Rome was fully repaid (meaning that, in Hellenic eyes, the treaty was now expired, though not so according to the Romans, who instead viewed the treaty as a permanent declaration of Carthaginian subordinance to Rome akin to the Roman treaties with her Italian allies) Numidia launched another border raid on Carthaginian soil, and in response Carthage launched a military expedition to repel the Numidian invaders.

As a result, Carthage suffered a humiliating military defeat and was charged with another fifty year debt to Numidia. Immediately thereafter, however, Rome showed displeasure with Carthage's decision to wage war against her neighbor without Roman consent, and told her that in order to avoid a war she had to "satisfy the Roman People." The Roman Senate then began gathering an army.

After Utica defected to Rome in 149 B.C., Rome declared war against Carthage. The Carthaginians made a series of attempts to negotiate with Rome, and received a promise that if three hundred children of well-born Carthaginians were sent as hostages to Rome the Carthaginians would keep the rights to their land and self-governance.

Even after this was done, however, the Romans landed an army at Utica where the Consuls demanded that Carthage hand over all weapons and armor. After those had been handed over, Rome additionally demanded that the Carthaginians move at least ten miles inland, while Carthage itself was burned. When the Carthaginians learned of this they abandoned negotiations and the city was immediately besieged, beginning the Third Punic War.

The Carthaginians endured the siege from 149 BC to 146 BC, when Scipio Aemilianus took the city by storm. Many Carthaginians died from starvation during the latter part of the siege, while many others died in the final six days of fighting. When the war ended, the remaining 50,000 Carthaginians (perhaps a tenth of the original pre-war population) were sold into slavery.

The city was systematically burned for somewhere between 10 and 17 days. Then the city walls, its buildings and its harbor were utterly destroyed and the surrounding territory was supposedly sown with salt to ensure that nothing would grow there again. The sowing may have been merely a symbolic curse against Rome's defeated enemy, or the account may be entirely invented; it does not appear in the records of the war, and historians today dispute whether it actually happened.

Roman Military