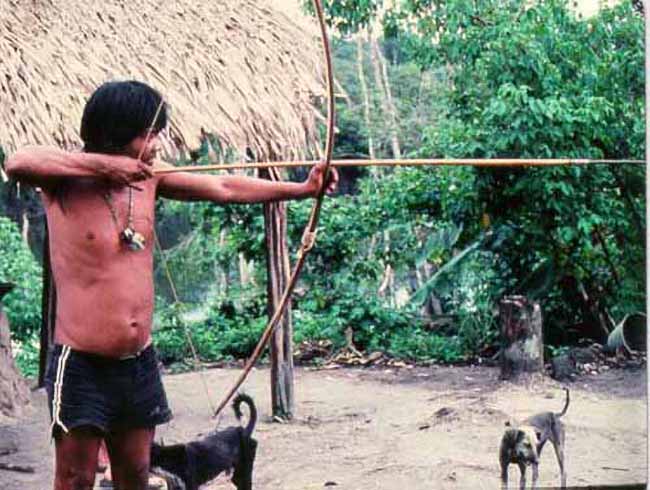

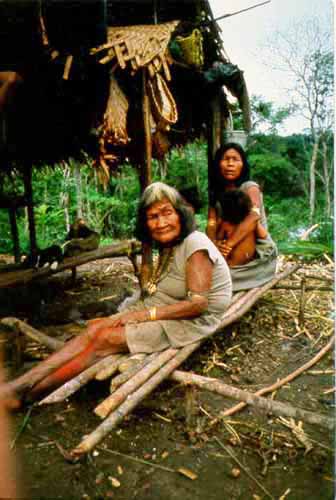

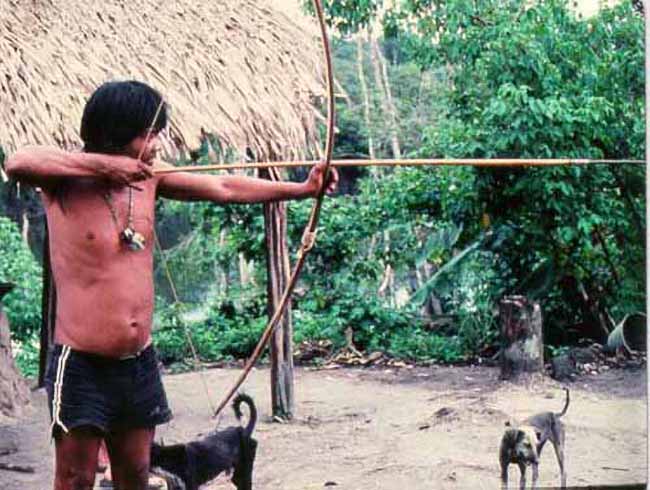

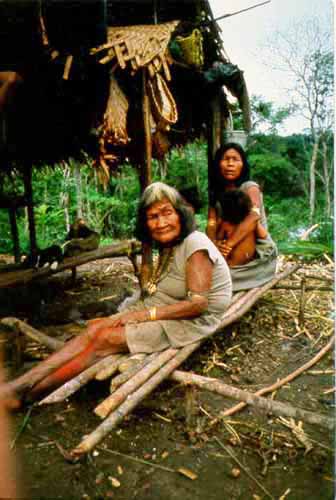

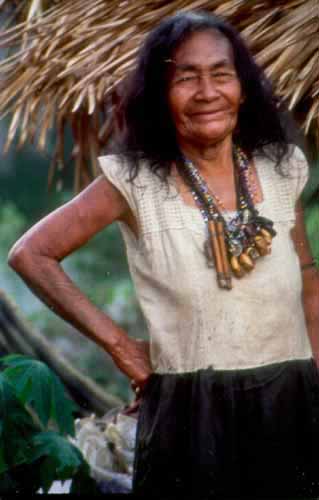

The Piraha are an indigenous hunter-gatherer tribe of Amazonian Indians in Brazil who mainly live on the banks of the Maici River. They are the sole surviving subgroup of the Mura people. They played an important part in Brazilian history during colonial times and were known for their quiet determination and subsequent resistance to the encroaching Portuguese culture. Formerly a powerful people, they were defeated by their neighbors, the Munduruku, in 1788.

They currently number about 800, which is sharply reduced from the numbers recorded in previous decades.

The Piraha people do not call themselves Pirahas but instead the Hi'aiti'ihi', roughly translated as 'the straight ones'.

Most take short naps of 15 minutes to two hours through the day and night, and rarely sleep through the night.

They often go hungry, not for want of food, but from a desire to be tigisai - "strong".

The Piraha do not have the usual origin stories about mythological gods who came to Earth, created humans, and will one day return. They have an understanding that something greater created the world and the people who dwell within it and follow celestial events to plan their destinies.

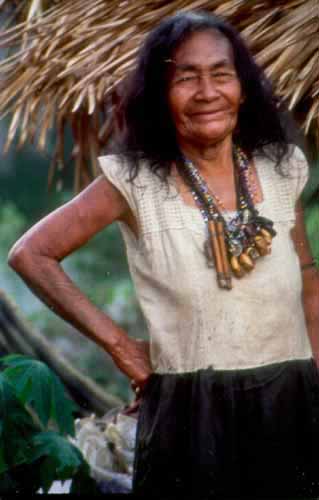

Their crafts and artwork consist mostly of beaded and shell jewelry and ornaments - as well as stick-figures to ward off evil spirits.

They are aware of outside civilizations but prefer to remain as they always existed for as long as nature and humanity allows them to do so.

The Piraha speak the Piraha language, which is very important to their culture and to their group identity. Members of the Piraha actually can whistle their language, which is how its men communicate when hunting in the jungle. The culture and language each have several unique traits, which it has been argued are related. Among these:

A�s� �f�a�r� �a�s� �t�h�e� �P�i�r�a�h�a �h�a�v�e� �r�e�l�a�t�e�d� �t�o� �r�e�s�e�a�r�c�h�e�r�s�,� �t�h�e�i�r� �c�u�l�t�u�r�e� �i�s� �c�o�n�c�e�r�n�e�d� �s�o�l�e�l�y� �w�i�t�h� �m�a�t�t�e�r�s� �t�h�a�t� �f�a�l�l� �w�i�t�h�i�n� �d�i�r�e�c�t� �p�e�r�s�o�n�a�l� �e�x�p�e�r�i�e�n�c�e�,� �a�n�d� �t�h�u�s� �t�h�e�r�e� �i�s� �n�o� �h�i�s�t�o�r�y� �b�e�y�o�n�d� �l�i�v�i�n�g� �m�e�m�o�r�y�.�As far as the Piraha have related to researchers, their culture is concerned solely with matters that fall within direct personal experience, and thus there is no history beyond living memory.

T�h�e� �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e� �i�s� �c�l�a�i�m�e�d� �t�o� �h�a�v�e� �n�o� �r�e�l�a�t�i�v�e� �c�l�a�u�s�e�s� �o�r� �g�r�a�m�m�a�t�i�c�a�l� �r�e�c�u�r�s�i�o�n�,� �b�u�t� �t�h�i�s� �i�s� �n�o�t� �c�l�e�a�r�.� �S�h�o�u�l�d� �t�h�e� �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e� �t�r�u�l�y� �f�e�a�t�u�r�e� �a� �l�a�c�k� �o�f� �r�e�c�u�r�s�i�o�n�,� �t�h�e�n� �i�t� �w�o�u�l�d� �b�e� �a� �c�o�u�n�t�e�r�e�x�a�m�p�l�e� �t�o� �t�h�e� �t�h�e�o�r�y� �p�r�o�p�o�s�e�d� �b�y� �C�h�o�m�s�k�y�,� �H�a�u�s�e�r� �a�n�d� �F�i�t�c�h� �(�2�0�0�2�)� �t�h�a�t� �r�e�c�u�r�s�i�o�n� �i�s� �a� �c�r�u�c�i�a�l� �a�n�d� �u�n�i�q�u�e�l�y� �h�u�m�a�n� �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e� �p�r�o�p�e�r�t�y�.

Its seven consonants and three vowels are the fewest known of any language.

The culture has the simplest known kinship system, not tracking relations any more distant than biological siblings.

The people do not count and the language does not have words for precise numbers. Despite efforts to teach them, researchers claim they seem incapable of learning numeracy.

I�t� �i�s� �s�u�s�p�e�c�t�e�d� �t�h�a�t� �t�h�e� �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e�'�s� �e�n�t�i�r�e� �p�r�o�n�o�u�n� �s�e�t�,� �w�h�i�c�h� �i�s� �t�h�e� �s�i�m�p�l�e�s�t� �o�f� �a�n�y� �k�n�o�w�n� �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e�,� �w�a�s� �r�e�c�e�n�t�l�y� �b�o�r�r�o�w�e�d� �f�r�o�m� �o�n�e� �o�f� �t�h�e� �T�u�p�l-�G�u�a�r�a�n�l �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e�s�,� �a�n�d� �t�h�a�t� �p�r�i�o�r� �t�o� �t�h�a�t� �t�h�e� �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e� �h�a�d� �n�o� �p�r�o�n�o�u�n�s� �w�h�a�t�s�o�e�v�e�r�.� �M�a�n�y� �l�i�n�g�u�i�s�t�s�,� �h�o�w�e�v�e�r�,� �f�i�n�d� �t�h�i�s� �c�l�a�i�m� �q�u�e�s�t�i�o�n�a�b�l�e�,� �n�o�t�i�n�g� �t�h�a�t� �t�h�e�r�e� �i�s� �n�o� �h�i�s�t�o�r�i�c�a�l�-�c�o�m�p�a�r�a�t�i�v�e� �e�v�i�d�e�n�c�e� �i�n�d�i�c�a�t�i�n�g� �t�h�e� �n�o�n�-�e�x�i�s�t�e�n�c�e� �o�f� �p�r�o�n�o�u�n�s� �i�n� �a� �p�r�e�v�i�o�u�s� �p�e�r�i�o�d� �o�f� �t�h�e� �h�i�s�t�o�r�y� �o�f� �P�i�r�a�ha� �a�l�s�o�,� �t�h�e� �o�v�e�r�a�l�l� �l�a�c�k� �o�f� �T�u�p�i�-�G�u�a�r�a�n�i� �l�o�a�n�w�o�r�d�s� �i�n� �a�r�e�a�s� �o�f� �t�h�e� �l�e�x�i�c�o�n� �m�o�r�e� �s�u�s�c�e�p�t�i�b�l�e� �t�o� �b�o�r�r�o�w�i�n�g� �(�s�u�c�h� �a�s� �n�o�u�n�s� �r�e�f�e�r�r�i�n�g� �t�o� �c�u�l�t�u�r�a�l� �i�t�e�m�s�,� �f�o�r� �i�n�s�t�a�n�c�e�)� �m�a�k�e�s� �t�h�i�s� �h�y�p�o�t�h�e�s�i�s� �e�v�e�n� �l�e�s�s� �p�l�a�u�s�i�b�l�e�.�

There is a disputed theory that the language has no color terminology. There are no unanalyzable root words for color; the color words recorded are all compounds like bi'i'sai, "blood-like", which is not that uncommon.

Spiegel Online - May 10, 2006

The Piraha people have no history, no descriptive words and no subordinate clauses. That makes their language one of the strangest in the world - and also one of the most hotly debated by linguists.

The language of the forest dwellers, which Dan Everett describes as "tremendously difficult to learn," so fascinate the researcher who spent a total of seven years living with the Pirahas - during which time he committed his career to researching their puzzling language.

Indeed, he was long so uncertain about what he was actually hearing while living among the Pirahas that he waited nearly three decades before publishing his findings.

What he found was enough to topple even the most-respected theories about the Pirahas' faculty of speech. The small hunting and gathering tribe, with a population of only 310 to 350, has become the center of a raging debate between linguists, anthropologists and cognitive researchers.

The debate over the people of the Maici River goes straight to the core of the riddle of how homo sapiens managed to develop vocal communication. Although bees dance, birds sing and humpback whales even sing with syntax, human language is unique. If for no other reason than for the fact that it enables humans to piece together never before constructed thoughts with ceaseless creativity - think of Shakespeare and his plays or Einstein and his theory of relativity.

Linguistics generally focuses on what idioms across the world have in common. But the Piraha language - and this is what makes it so significant - departs from what were long thought to be essential features of all languages.

The language is incredibly spare. The Piraha use only three pronouns. They hardly use any words associated with time and past tense verb conjugations don't exist. Apparently colors aren't very important to the Pirahas, either - they don't describe any of them in their language. But of all the curiosities, the one that bugs linguists the most is that Piraha is likely the only language in the world that doesn't use subordinate clauses. Instead of saying, "When I have finished eating, I would like to speak with you," the Pirahas say, "I finish eating, I speak with you."

Equally perplexing: In their everyday lives, the Pirahas appear to have no need for numbers. During the time he spent with them, Everett never once heard words like "all," "every," and "more" from the Pirahas. There is one word, "hoi," which does come close to the numeral 1. But it can also mean "small" or describe a relatively small amount - like two small fish as opposed to one big fish, for example. And they don't even appear to count without language, on their fingers for example, in order to determine how many pieces of meat they have to grill for the villagers, how many days of meat they have left from the anteaters they've hunted or how much they demand from Brazilian traders for their six baskets of Brazil nuts.

The debate amongst linguists about the absence of all numbers in the Piraha language broke out after Peter Gordon, a psycholinguist at New York's Columbia University, visited the Pirahas and tested their mathematical abilities. For example, they were asked to repeat patterns created with between one and 10 small batteries. Or they were to remember whether Gordon had placed three or eight nuts in a can.

The results, published in Science magazine, were astonishing. The Pirahas simply don't get the concept of numbers. His study, Gordon says, shows that "a people without terms for numbers doesn't develop the ability to determine exact numbers."

Psycholinguist Peter Gorden: Are we only capable of creating thoughts for which words exist? His findings have brought new life to a controversial theory by linguist Benjamin Whorf, who died in 1914. Under Whorf's theory, people are only capable of constructing thoughts for which they possess actual words. In other words: Because they have no words for numbers, they can't even begin to understand the concept of numbers and arithmetic.

But then, coming to terms with something like Portuguese multiplication tables would require the forest-dwellers to acquire some basic arithmetic.

The Warlpiri - a group of Australian aborigines whose language, like that of the Piraha, only has a "one-two-many," system of counting - had no difficulties counting farther than three in English.

But the Pirahas proved to be completely different. Years ago, Everett attempted to teach them to learn to count. Over a period of eight months, he tried in vain to teach them the Portuguese numbers used by the Brazilians - um, dois, tres. "In the end, not a single person could count to ten," the researcher says.

It's certainly not that the jungle people are too dumb. "Their thinking isn't any slower than the average college freshman," Everett says. Besides, the Pirahas don't exactly live in genetic isolation - they also mix with people from the surrounding populations. In that sense, their intellectual capacities must be equal to those of their neighbors.

Eventually Everett came up with a surprising explanation for the peculiarities of the Piraha idiom. "The language is created by the culture," says the linguist. He explains the core of Piraha culture with a simple formula: "Live here and now." The only thing of importance that is worth communicating to others is what is being experienced at that very moment. "All experience is anchored in the presence," says Everett, who believes this carpe-diem culture doesn't allow for abstract thought or complicated connections to the past - limiting the language accordingly.

Living in the now also fits with the fact that the Piraha don't appear to have a creation myth explaining existence. When asked, they simply reply: "Everything is the same, things always are." The mothers also don't tell their children fairy tales - actually nobody tells any kind of stories. No one paints and there is no art.

Even the names the villagers give to their children aren't particularly imaginative. Often they are named after other members of the tribe which whom they share similar traits. Whatever isn't important in the present is quickly forgotten by the Piraha. "Very few can remember the names of all four grandparents," says Everett.

The scientist is convinced that linguists will find a similar cultural influence on language elsewhere if they look for it. But up till now many defend the widely accepted theories from Chomsky, according to which all human languages have a universal grammar that form a sort of basic rules enabling children to put meaning and syntax to a combination of words.

Whether phonetics, semantics or morphology - what exactly makes up this universal grammar is controversial. At its core, however, is the concept of recursion, which is defined as replication of a structure within its single parts. Without it, there wouldn't be any mathematics, computers, philosophy or symphonies. Humans basically wouldn't be able to view separate thoughts as subordinate parts of a complex idea.

And there wouldn't be subordinate clauses. They are responsible for translating the concept of recursion into grammar. Renowned US psychologist Pinker believes that if the Piraha don't form subordinate clauses, then recursion cannot explain the uniqueness of human language - just as it cannot be a central element of some universal grammar. Chomsky would be refuted.

The logical way forward now would be to try to prove that the Piraha can actually think in a recursive fashion. According to Everett, the only reason this isn't part of their language is because it is forbidden by their culture. The only problem is nobody can confirm or deny Everett's observations since no one can speak Piraha as well as he does.

Despite this, several researchers - including two Chomsky colleagues - will travel this year to Maici to try and check parts of his claims. But for some, it's already getting too crowded in the jungle. "I'm concerned the Piraha will simply become one more scientific oddity, to be exploited and analyzed right down to their feces," complains Peter Gordon.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS