The Mixtec are indigenous Mesoamerican peoples inhabiting the modern day Mexican states of Oaxaca, Guerrero and Puebla in a region known as La Mixteca. The Mixtecan languages form an important branch of the Otomanguean linguistic family.

In pre-Columbian times, the Mixtec were one of the major civilizations of Mesoamerica. Important ancient centers of the Mixtec include the ancient capital of Tilantongo, as well as the sites of Achiutla, Cuilapan, Huajuapan, Mitla, Tlaxiaco, Tututepec, Juxtlahuaca, and Yucu–udahui.

The term Mixtec (Mixteco in Spanish) comes from the Nahuatl word Mixtecapan, or "place of the cloud-people" or "people of the rain place."

In pre-Columbian times, the Mixtec were one of the major civilizations of Mesoamerica. Important ancient centres of the Mixtec include the ancient capital of Tilantongo, as well as the sites of Achiutla, Cuilapan, Huajuapan, Mitla, Tlaxiaco, Tututepec, Juxtlahuaca, and Yucu–udahui. The Mixtec also made major constructions at the ancient city of Monte Alb‡n (which had originated as a Zapotec city before the Mixtec gained control of it). The work of Mixtec artisans who produced work in stone, wood, and metal were well regarded throughout ancient Mesoamerica.

At the height of the Aztec Empire, many Mixtecs paid tribute to the Aztecs, but not all Mixtec towns became vassals. They put up resistance to Spanish rule until they were subdued by the Spanish and their central Mexican allies led by Pedro de Alvarado.

Today, Mixtecs have migrated to various parts of both Mexico and the United States. In recent years a large exodus of indigenous peoples from Oaxaca, such as the Zapotec and Triqui, have emerged as one of the most numerous groups of Amerindians in the United States. Large Mixtec communities exist in the border cities of Tijuana, Baja California, San Diego, California and Tucson, Arizona. Mixtec communities are generally described as trans-national or trans-border because of their ability to maintain and reaffirm social ties between their native homelands and diasporic community.

The symbolism and iconography of writing systems found throughout the ancient world are fascinating, but none more than those that evolved in ancient Mesoamerica. Developing independently of Mediterranean or Asian cultures, there are several different types of pre-conquest writing that represent a unique intellectual achievement in this part of the new world.

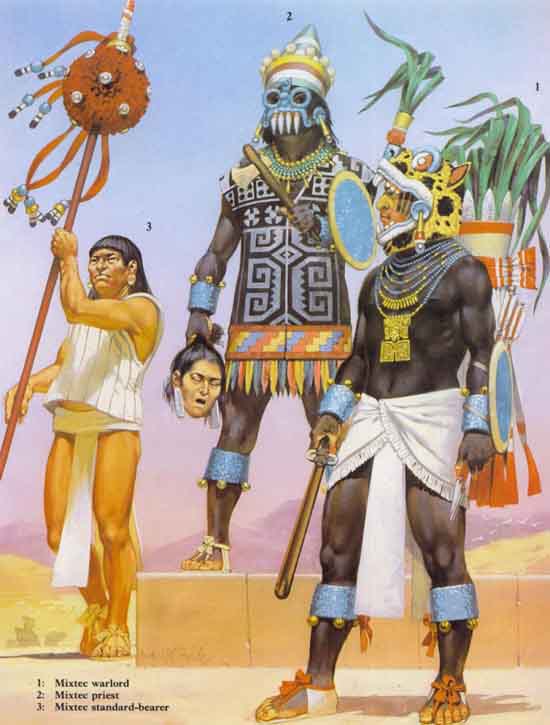

The Mixtecs were one of the most influential ethnic groups to emerge in Mesoamerica during the Post-Classic. Never an united nation, the Mixtecs waged war and forged alliances among themselves as well as with other peoples in their vicinity. They also produced beautiful manuscripts and great metal work, and influenced the international artistic style used from Central Mexico to Yucatan.

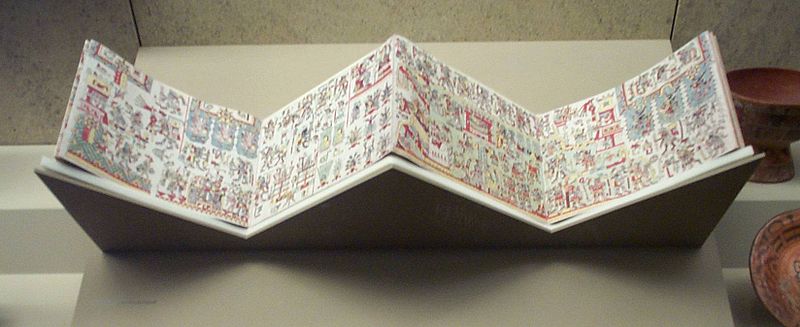

During the Classic period, the Mixtecs lived in hilltop settlements of northwestern Oaxaca, a fact which is reflected in their name in their own language, „uudzahui, meaning "People of the Rain". Later, during the Post-Classic, the Mixtecs slowly moved into adjacent valleys and then into the great Valley of Oaxaca. This time of expansion is no doubt recorded in a large number of deerskin manuscripts, only eight of which have survived. Nevertheless, these manuscripts allow us to trace Mixtec history from 1550 CE back to 940 CE, deeper in time than any other Mesoamerican culture except the Maya.

Even though surrounded by more textual writing systems, the Mixtecs opted to write in a more minimalistic manner. Mixtec "writing" is really an amalgam of written signs and pictures. In particular, pictorial scenes would depict historical events such as birth, marriage, coronation, war, and death, while written glyphs would record the date of the event and identify the people and places involved.

The above example came from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall. It depicts a group of warriors conquering a town (an event noted by the warriors' drawn weapons and the arrow piercing the hill). You might notice glyphs with dots above each of the participants in the scene. The logical conclusion is that the glyphs are names, but in fact these are calendrical day signs. The reason for this is that among Mixtec nobles, a person's name is often his or her birthday.

Like other Mesoamerican cultures, the Mixtec used a 260-day sacred calendar. A day is a combination of a number, called the coefficient, and a day sign. The coefficient ranges from 1 to 13, while the day sign is any of the following 20 glyphs:

Unlike the Western system of months and days, the Mesoamerican sacred calendar moves the coefficient AND the day sign in parallel. You start with 1 Crocodile, then you move ahead both the number and the day sign, going to 2 Wind on the next day. You keep going until you end up with 13 Reed, then you rewind the numbers but continue with the day sign, hence yielding 1 Jaguar. When you've exhausted all day signs and you're at 7 Flower, you rewind the day signs to Crocodile but continue with the number, giving you 8 Crocodile.

Another interesting note is that Mixtecs did not use the bar to represent the quantity 5 in manuscripts, but instead used five dots. However, on monumental inscriptions, they did use the bar notation instead of five dots (see below).

The Mixtecs also had a 365-day solar calendar, but they did not record dates in this calendar. Instead, they interlocked the solar and the sacred calendars into the Calendar Round, a 52-year cycle commonly used in Mesoamerica. (Here's the math: the smallest number divisible by both 365 and 260 is 18980, which is 52 years.) Historical events in Mixtec manuscripts and monuments are dated by a year in the Calendar Round and a day in the sacred calendar.

Like the sacred calendar days, years in the Calendar Round are also composed of a number and a year sign. The number ranges from 1 to 13, and there are 4 year signs (hence yielding 52 years). The year sign is always infixed inside a glyph that scholars call the AO sign because it looks the letters A and O entertwined.

The four year signs are taken from the sacred calendar. They are rabbit, reed, flint, and house. The following are examples of year signs with coefficients:

The Mixtec are well-known in the anthropological world for their Codices, or phonetic pictures in which they wrote their history and genealogies in deerskin in the "fold-book" form. The best known story of the Mixtec Codices is that of Lord Eight Deer, named after the day in which he was born, whose personal name is Jaguar Claw, and whose epic history is related in several codices, including the Codex Bodley and Codex Zouche-Nuttall. He successfully conquered and united most of the Mixteca region.

The Codex Zouche-Nuttall is an accordion-folded pre-Columbian piece of Mixtec writing, now in the British Museum. It is one of three codices that record the genealogies, alliances and conquests of several 11th and 12th century rulers of a small Mixtec city-state in highland Oaxaca, the Tilantongo kingdom, especially under the leadership of the warrior Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw (who died early twelfth century at the age of fifty-two).

The Codex Zouche-Nuttall was made in the 14th century. The codex probably reached Spain in the 16th century. It was first identified at the Monastery of San Marco, Florence, in 1854 and was sold in 1859. A facsimile was published while it was in the collection of Robert Nathaniel Cecil George Curzon, Lord Zouche of Haryngworth by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard in 1902, with an introduction by Zelia Nuttall (1857-1933). The British Museum acquired it in 1917.

Mixtec religion worshipped the forces of nature including life, death and an afterlife. The sun was the deity held in highest esteem. Humans were tasked with maintaining the balance among men, nature, and the supernatural world through conscious acts of private and social ritual.

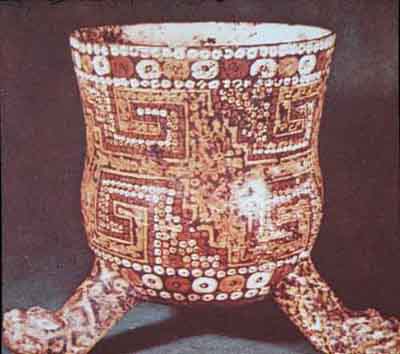

Blood sacrifice from the ears and tongue, and bird feathers were sometimes offered in purified vessels as gifts to the gods. These rituals were accompanied by dances that sometimes included human heart and animal sacrifices. Fire ceremonies indicated a renewal of the world and a granting of a new epoch given by the gods who were satisfied by the offerings provided to them.

The Mixtec were known for their exceptional mastery of jewelry, in which gold and turquoise figure prominently. The production of Mixtec goldsmiths formed an important part of the tribute the Mixtecs had to pay to the Aztecs during parts of their history.

Circa 900 - 1520 CE.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF ALL FILES