Myth, Math, Magic, and Mystery

Myth, Math, Magic, and Mystery

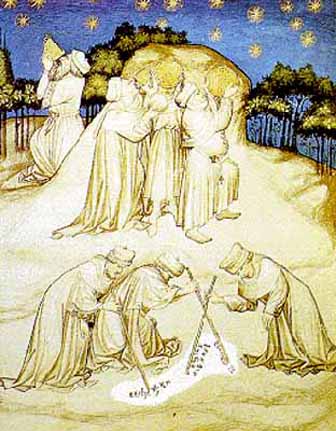

The Magi were Zoroastrian priests - part of early religions of western Iran. The earliest known use of the word Magi is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius the Great, known as the Behistun Inscription ("the place of god"). Magi were the practitioners of magic, including astronomy, astrology, alchemy, and other forms of esoteric knowledge. Ancient Alien Theory posits, the Magi, like Jesus, were aliens - the Star of Bethlehem a UFO.

Persian Prophet, Anunnaki, History, Myth, Aliens, More

Humans came out of Africa in the sense that the Great Pyramid Experiment

started there at the Dawn of Time when the script of our reality was first written.

Holidays such as Christmas and Easter take us to the Jesus storyline. Are they factual or altered through the centuries making them legends? If factual was Jesus a human, an alien, or both (hybrid)? Is Jesus coming back or is that storyline finished? Why were the UFOs depicted in the paintings below placed there? We know the artists saw them in their minds but why were they programmed to see spaceships?

Were the Zoroastrian Magi aliens? - Zoroaster

A disk shaped object is shining beams of light down on John the Baptist and Jesus - Fitzwilliam Musuem, Cambridge, England - Painted in 1710 by Flemish artist Aert De Gelder. It depicts a classic, hovering, silvery, saucer shaped UFO shining beams of light down on John the Baptist and Jesus. What could have inspired the artist to combine these two subjects?

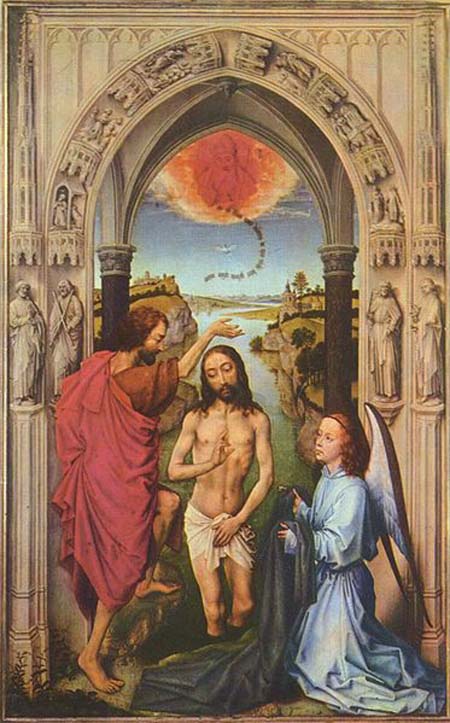

Baptism of Christ by Rogier van der Weyden (12th Century)

Baptism of Christ by Ottavio Vannini c. 1640

Baptism of Christ by Fra Angelico c. 1425

17th century fresco of the crucifixion

Svetishoveli Cathedral in Mtskheta, Georgia

Note the two saucer shaped craft on either side of Christ.

Painted by Paolo Uccello - circa 1460-1465

Frescos throughout Europe reveal the appearance of spaceships. This 1350 painting seems to depict a small human looking man looking over his shoulder at another flying vehicle. His vehicle is decorated with two twinkling stars, one reminiscent of national insignia on modern aircraft. This painting hangs above the altar at the Visoki Decani Monestary in Kosovo, Yugoslavia.

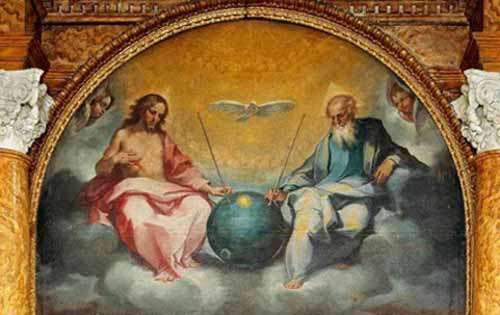

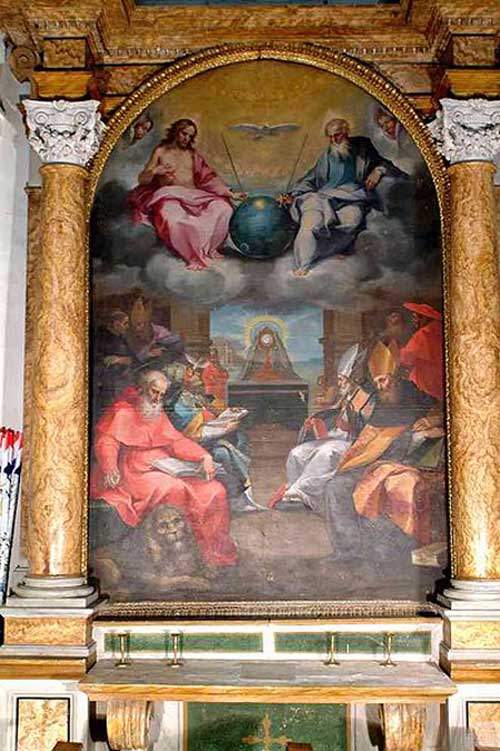

Glorification of the Eucharist - by Bonaventura Salimbeni in 1600

Today it hangs in the church of San Lorenzo in San Pietro, Montalcino, Italy.

What does the 'Sputnik satellite-like device' represent?

A fourteenth century fresco of the Madonna and Child depict on the top right side the image of a UFO hovering in the distance. A blow up of this fresco reveals tremendous details about this UFO including port holes. It seems to indicate a religious involvement between UFO's and the appearance of the Christ Child.

This painting is called "The Madonna with Saint Giovannino". It was painted in the 15th century by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494) and hangs as part of the Loeser collection in the Palazzo Vecchio. Above Mary's right shoulder is a disk shaped object. Below is a blow up of this section and a man and his dog can clearly be seen looking up at the object.

1330 - "The Magnificent" - Notre-Dame in Beaune, Burgandy

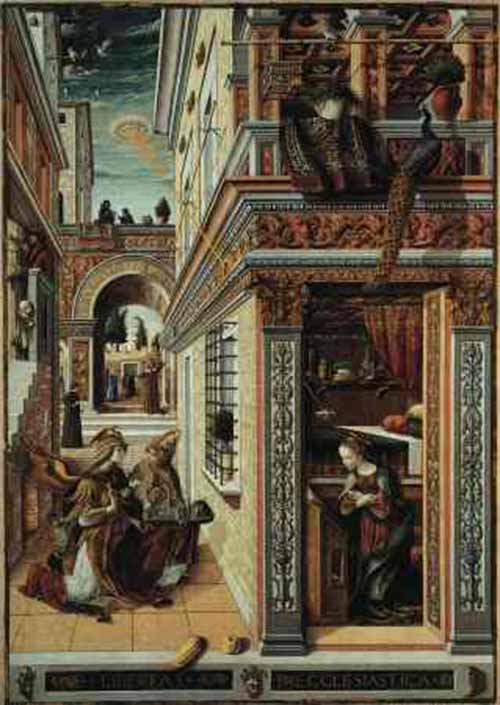

"The Annunciation with Saint Emidius" (1486) by Carlo Crivelli

It hangs in the National Gallery, London.

The picture above depicts Jesus and Mary and either UFOs or lenticular clouds. The painting is entitled "The Miracle of the Snow" and was painted by Masolino Da Panicale (1383-1440) and hangs at the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Florence, Italy. The bible references flying objects that were perhaps UFOs many go back to Flood Stories.

San Francesco Church in Arezzo, Italy

�A Magus (plural Magi, from Latin, from Old Persian magu; Old English: Mage) was a Zoroastrian astrologer-priest from ancient Persia. The best known Magi are the "Wise Men from the East" in the Bible. In English, the term may refer to a shaman, sorcerer, or wizard; it is the origin of the English words magic and magician.

Greek-Persian roots - The Greek word is attested from the 5th century BC (Ancient Greek) as a direct loan from Old Persian 'magus'. The Persian word is a u-stem adjective from an Indo-Iranian root *magh "powerful, rich" also continued in Sanskrit magha "gift, wealth", magha-vant "generous" (a name of Indra). Avestan has maga, magauuan, probably with the meanings "sacrifice" and "sacrificer". The PIE root (*magh-) appears to have expressed power or ability, continued e.g. in Attic Greek mekhos (cf. mechanics) and in Germanic magan (English may), magts (English might, the expression "might and magic" thus being a figura etymologica). The original significance of the name for the Median priests thus seems to have been "the powerful". Modern Persian Mobed is derived from an Old Persian compound magu-pati "lord priest".

As early as the 5th century BCE, Greek magos had spawned mageia and magike to describe the activity of a magus, that is, it was his or her art and practice. But almost from the outset the noun for the action and the noun for the actor parted company. Thereafter, mageia was used not for what actual magi did, but for something related to the word 'magic' in the modern sense, i.e. using supernatural means to achieve an effect in the natural world, or the appearance of achieving these effects through trickery or sleight of hand. The early Greek texts typically have the pejorative meaning, which in turn influenced the meaning of magos to denote a conjurer and a charlatan. Already in the mid-5th century BC, Herodotus identifies the magi as interpreters of omens and dreams (Histories 7.19, 7.37, 1.107, 1.108, 1.120, 1.128).

Once the magi had been associated with "magic" - Greek magikos - it was but a natural progression that the Greeks' image of Zoroaster would metamorphose into a magician too. The first century Pliny the elder names "Zoroaster" as the inventor of magic (Natural History xxx.2.3), but a "principle of the division of labor appears to have spared Zoroaster most of the responsibility for introducing the dark arts to the Greek and Roman worlds. That dubious honor went to another fabulous magus, Ostanes, to whom most of the pseudepigraphic magical literature was attributed."

For Pliny, this magic was a "monstrous craft" that gave the Greeks not only a "lust" (aviditatem) for magic, but a downright "madness" (rabiem) for it, and Pliny supposed that Greek philosophers - among them Pythagoras, Empedocles, Democritus, and Plato - traveled abroad to study it, and then returned to teach it.

Zoroaster - or rather what the Greeks supposed him to be - was for the Hellenists the figurehead of the 'magi', and the founder of that order (or what the Greeks considered to be an order). He was further projected as the author of a vast compendium of "Zoroastrian" pseudepigrapha, composed in the main to discredit the texts of rivals. "The Greeks considered the best wisdom to be exotic wisdom" and "what better and more convenient authority than the distant - temporally and geographically - Zoroaster?

One factor for the association with astrology was Zoroaster's name, or rather, what the Greeks made of it. Within the scheme of Greek thinking (which was always on the lookout for hidden significances and "real" meanings of words) his name was identified at first with star-worshiping (astrothytes "star sacrificer") and, with the Zo-, even as the living star. Later, an even more elaborate mytho-etymology evolved: Zoroaster died by the living (zo-) flux (-ro-) of fire from the star (-astr-) which he himself had invoked, and even, that the stars killed him in revenge for having been restrained by him.

The second, and "more serious" factor for the association with astrology was the notion that Zoroaster was a Chaldean. The alternate Greek name for Zoroaster was Zaratas/Zaradas/Zaratos (cf. Agathias 2.23–5, Clement Stromata I.15), which - according to Bidez and Cumont—derived from a Semitic form of his name. The Pythagorean tradition considered the "founder" of their order to have studied with Zoroaster in Chaldea (Porphyry Life of Pythagoras 12, Alexander Polyhistor apud Clement's Stromata I.15, Diodorus of Eritrea, Aristoxenus apud Hippolitus VI32.2). Lydus (On the Months II.4) attributes the creation of the seven-day week to "the Chaldeans in the circle of Zoroaster and Hystaspes", and who did so because there were seven planets. The Suda's chapter on astronomia notes that the Babylonians learned their astrology from Zoroaster. Lucian of Samosata (Mennipus 6) decides to journey to Babylon "to ask one of the magi, Zoroaster's disciples and successors", for their opinion.

According to Herodotus, the Magi were the sacred caste of the Medes. They organized Persian society after the fall of Assyria and Babylon. Their power was curtailed by Cyrus, the founder of the Persian Empire, and by his son Cambyses II; the Magi revolted against Cambyses and set up a rival claimant to the throne, one of their own, who took the name of Smerdis. Smerdis and his forces were defeated by the Persians under Darius I. The sect of the Magi continued in Persia, though its influence was limited after this political setback.

During the Classical era (555 BC - 300 AD), some Magi migrated westward, settling in Greece, and then Italy. For more than a century, Mithraism, a religion derived from Persia, was the largest single religion in Rome. The Magi were likely involved in its practice.

The Book of Jeremiah (39:3, 39:13) gives a title rab mag "chief magus" to the head of the Magi, Nergal Sharezar (Septuagint, Vulgate and KJV mistranslate Rabmag as a separate character). It's also believed by Christians that the Jewish prophet Daniel was "rab mag" and entrusted a Messianic vision (to be announced in due time by a "star") to a secret sect of the Magi for its eventual fulfillment (Daniel 4:9; 5: 11).

The oldest surviving Greek reference to the magi – from Greek "Magos" might be from 6th century BCE Heraclitus (apud Clemens Protrepticus 12), who curses the magi for their "impious" rites and rituals. A description of the rituals that Heraclitus refers to has not survived, and there is nothing to suggest that Heraclitus was referring to foreigners.

Better preserved are the descriptions of the mid-5th century BCE Herodotus, who in his portrayal of the Iranian expatriates living in Asia minor uses the term "magi" in two different senses. In the first sense (Histories 1.101), Herodotus speaks of the magi as one of the tribes/peoples (ethnous) of the Medes. In another sense (1.132), Herodotus uses the term "magi" to generically refer to a "sacerdotal caste", but "whose ethnic origin is never again so much as mentioned." According to Robert Charles Zaehner, in other accounts, "we hear of Magi not only in Persia, Parthia, Bactria, Chorasmia, Aria, Media, and among the Sakas, but also in non-Iranian lands like Samaria, Ethiopia, and Egypt. Their influence was also widespread throughout Asia Minor. It is, therefore, quite likely that the sacerdotal caste of the Magi was distinct from the Median tribe of the same name."

Other Greek sources from before the Hellenistic period include the gentleman-soldier Xenophon, who had first-hand experience at the Persian Achaemenid court. In his early 4th century BCE Cyropaedia, Xenophon depicts the magians as authorities for all religious matters (8.3.11), and imagines the magians to be responsible for the education of the emperor-to-be.

The Zoroastrians form a very small ethnic group in India known as the Parsis. After invading Arabs succeeded in taking Ctesiphon in 637, Islam largely superseded Zoroastrianism, and the power of the Magi faded. Many (but not all) of the mages fled the advent of Islam in Persia, or Iran, by emigrating to India, settling in western principalities which form the modern states of Gujarat and Maharastra. As one can only be Zoroastrian by birth, the number of Parsis and Zoroastrians in the world is shrinking, and the remaining population risks passing down genetic defects as with any small community. Suffice to say Parsis are very rare, and Magi are even rarer.

In India there is a community termed Maga, Bhojaka or Shakadvipi Brahmins. Their major centers are in Rajasthan in Western India and near Gaya in Bihar. According to Bhavishya Purana and other texts, they were invited to settle in Punjab to conduct the worship of Lord Sun (Mitra or Surya in Sanskrit). Bhavishya Purana explicitly identifies them with Zoroastrianism.

The members of the community still worship in Sun temples in India. They are also heriditary priests in several Jain temples in Gujarat and Rajasthan. Bhojakas are mentioned in the the copperplates of of the Kadamba dynasty (4-6th cent) as managers of Jain institutions.Images of Lord Sun in India are shown wearing a central asian dress, complete with boots. The term "Mihir" in India is regarded to represent the Maga influence.

A painting in the cemetery of Saint Peter and Saint Marcellinus shows two Magi;

A painting in the Lateran Museum, shows three Magi;

A painting in the cemetery of Domitilla, shows four Magi;

A vase in the Kircher Museum, shows eight Magi (Paris, 1899)

The Star of Bethlehem, also called the Christmas Star, is a star in Christian tradition that revealed the birth of Jesus to the magi, or "wise men", and later led them to Bethlehem. According to the Gospel of Matthew, the magi were men "from the east" who were inspired by the appearance of the star to travel to Jerusalem.

There they met King Herod of Judea, and asked where the king of the Jews had been born. Herod then asked his advisers where a messiah could be born. They replied Bethlehem, a nearby village, and quoted a prophecy by Micah. While the magi were on their way to Bethlehem, the star appeared again. Following the star, which stopped above the place where Jesus was born, the magi found Jesus with his mother, paid him homage, worshipped him and gave gifts. They then returned to their "own country".

Many Christians see the star as a miraculous sign to mark the birth of the christ (or messiah). Some theologians claimed that the star fulfilled a prophecy, known as the Star Prophecy. In modern times, astronomers have proposed various explanations for the star. A nova, a planet, a comet, an occultation, and a conjunction (gathering of planets) have all been suggested.

Many scholars question the historical accuracy of the story and argue that the star was a fiction created by the author of the Gospel of Matthew.

The subject is a favorite at planetarium shows during the Christmas season, although the Biblical account suggests that the visit of the magi took place at least several months after Jesus was born. The visit is traditionally celebrated on Epiphany (January 6) in Western Christianity and on Christmas (December 25) in Eastern Christianity.

Some people feel the Star of Bethlehem was a comet, shooting star, or perhaps a UFO.

Wondering about the 'Star of Wonder' - Was it a comet? A supernova? Science suggests something else. - NBC - December 9, 2008

The Magi linked the appearance of a star to the birth of a "King of the Jews."

In Hellenistic astrology, Jupiter was the king planet and Regulus (in the constellation Leo) was the king star. As they traveled from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, the star "went before" the magi and then "stood over" the place where Jesus was. In astrological interpretations, these phrases are said to refer to retrograde motion and to stationing, i.e., Jupiter appeared to reverse course for a time, then stopped, and finally resumed its normal progression.

In 3-2 BC, there was a series of seven conjunctions, including three between Jupiter and Regulus and a strikingly close conjunction between Jupiter and Venus near Regulus on June 17, 2 BC. "The fusion of two planets would have been a rare and awe-inspiring event", according to a paper by Roger Sinnott. This event however occurred after the generally accepted date of 4 BC for the death of Herod. Since the conjunction would have been seen in the west at sunset it could not have led the magi south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem.

Astronomer Michael Molnar has proposed a link between a double occultation of Jupiter by the moon in 6 BC in Aries and the Star of Bethlehem, particularly the second occultation on April 17. This event was quite close to the sun and would have been difficult to observe, even with a small telescope, which had not yet been invented.

Occultations of planets by the moon are quite common, but Firmicus Maternus, an astrologer to Roman Emperor Constantine, wrote that an occultation of Jupiter in Aries was a sign of the birth of a divine king. "When the royal star of Zeus, the planet Jupiter, was in the east this was the most powerful time to confer kingships. Furthermore, the Sun was in Aries where it is exalted. And the Moon was in very close conjunction with Jupiter in Aries", Molnar wrote.

A celestial event is oftentimes the precursor to the fulfillment of a prophecy from god about great change on the planet and for humanity in general. This celestial sighting would have been part of a prophecy about the birth of a great prophet/king who would change the thinking of the world forever.