1914

1914

The Iroquois also known as the Haudenosaunee or the "People of the Longhouse", are a league of several nations and tribes of indigenous people of North America. After the Iroquoian-speaking peoples of present-day central and upstate New York coalesced as distinct tribes, by the 16th century or earlier, they came together in an association known today as the Iroquois League, or the "League of Peace and Power".

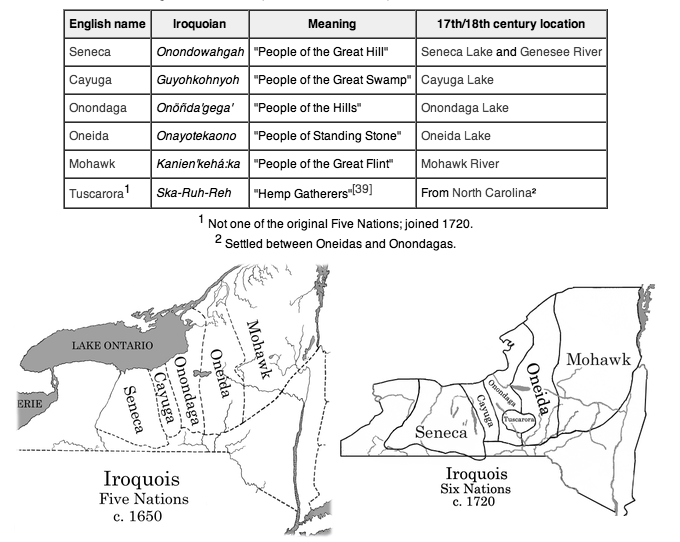

The original Iroquois League was often known as the Five Nations, as it was composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca nations. After the Tuscarora nation joined the League in 1722, the Iroquois became known as the Six Nations. The League is embodied in the Grand Council, an assembly of fifty hereditary sachems. Other Iroquian peoples lived along the St. Lawrence River, around the Great Lakes and in the American Southeast, but they were not part of the Haudenosaunee and often competed and warred with these tribes.

When Europeans first arrived in North America, the Haudenosaunee were based in what is now the northeastern United States, primarily in what is referred to today as upstate New York west of the Hudson River and through the Finger Lakes region. Today, the Iroquois live primarily in New York, Quebec, and Ontario.

The Iroquois League has also been known as the Iroquois Confederacy. Some modern scholars distinguish between the League and the Confederacy. According to this interpretation, the Iroquois League refers to the ceremonial and cultural institution embodied in the Grand Council, while the Iroquois Confederacy was the decentralized political and diplomatic entity that emerged in response to European colonization. The League still exists. The Confederacy dissolved after the defeat of the British and allied Iroquois nations in the American Revolutionary War.

The Iroquois call themselves the "Haudenosaunee", which means "People of the Longhouse," or more accurately, "They Are Building a Long House." According to their tradition, The Great Peacemaker introduced the name at the time of the formation of the League. It implies that the nations of the League should live together as families in the same longhouse. Symbolically, the Mohawk were the guardians of the eastern door, as they were located in the east closest to the Hudson, and the Seneca were the guardians of the western door of the "tribal longhouse", the territory they controlled in New York. The Onondaga, whose homeland was in the center of Haudenosaunee territory, were keepers of the League's (both literal and figurative) central flame. The French colonists called the Haudenosaunee by the name of Iroquois. The name had various possible origins, both learned by the French from tribes who were enemies of the Haudenosaunee.

Seneca

The Seneca are a Native American people, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois League. About 10,000 Seneca Indians live in the United States and Canada, primarily on reservations in western New York state, with others living in Oklahoma and near Brantford, Ontario.

The Seneca, or "Onodowohgah" ("People of the Hill Top"), traditionally lived in what is now New York between the Genesee River and Canandaigua Lake. With the prehistoric formation of the Iroquois Confederation, the Seneca became known the "Keepers of the Western Door" because they were located on the western edge of the Iroquois domain. The Senecas were by far the largest of the Iroquois nations.

Traditionally, the economy was based on cultivation of corn, beans, and squash (the three sisters), primarily by the women, and hunting and fishing by the men. During the colonial period they became involved in the fur trade, first with the Dutch and then with the British. This served to increase hostility with other native groups, especially their traditional enemy, the Huron, an Iroquoian tribe in New France near Lake Simcoe. During the 17th century, attacks on Huron villages caused the destruction and dispersal of the Huron. Captives who were not tortured to death were adopted into the tribe.

During the American Revolution, the Seneca along with their immediate neighbor in the League, the Cayuga, carried out many raids on American settlements and strongholds, instigated by the British at Fort Niagara. These raids were reduced after the Clinton and Sullivan Expedition destroyed many Cayuga villages. Divisions in the League from mixed loyalties of its members to the British or Americans weakened its power.

On November 11, 1794, the Seneca (along with the other Haudenosaunee nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States.

The Seneca, like other League members, were known as the People of the Long House. They lived in villages, often surrounded by palisades due to warfare, which moved every ten or fifteen years as soil and game were depleted. During the 19th century they adopted many of the customs of their white neighbors, building log cabins and participating in the local agricultural economy.

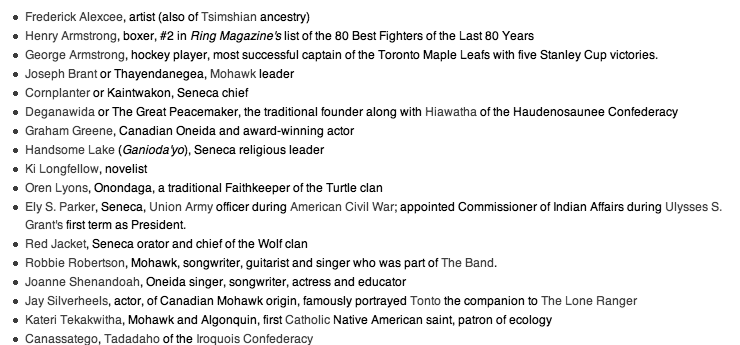

Notable Senecas in history include Red Jacket, Cornplanter, Guyasuta, Handsome Lake, and Ely S. Parker.

Today the Seneca formed a modern government, the Seneca Nation of Indians, in 1848, but the traditional tribal government still retains some power. Today some Seneca are involved in the sale of (untaxed) low-priced gasoline and cigarettes and high-stakes bingo. They are debating their involvement in legalized gambling on reservation lands. Others are employed in the local economy of the region.

About 7200 enrolled members live on three reservations in New York: the Allegany (which contains the city of Salamanca), the Cattaraugus near Gowanda, New York, and the Oil Springs, near Cuba, New York. Few, if any, Seneca reside at Oil Springs.

An independent group live on the Tonawanda Reservation near Akron, New York. Other Seneca live in association with the Cayuga in Miami, Oklahoma or on the Six Nations of the Grand River reserves near Brantford, Ontario, Canada.

The Cayuga nation (Guyohkohnyo or the People of the Great Swamp) was one of the five original constituents of the Iroquois, a confederacy of Indians in New York. The Cayuga homeland lay in the Finger Lakes region between their league neighbors, the Onondaga and the Seneca.

Due to many attacks on American colonists during the American Revolution, the punitive Sullivan Expedition devastated the Cayuga homeland. Survivors fled to other Iroquois tribes or to Canada. Today, there are three Cayuga bands. The two largest are the Lower Cayuga and Upper Cayuga, both at Six Nations of the Grand River. Only a small number remain in New York with the Cayuga Nation in Versailles. After the Mohawks, the Cayugas are the most numerous people at Six Nations.

On November 11, 1794, the Cayuga Nation (along with the other Haudenosaunee nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States.

The Onondaga (Onundagaono or the People of the Hills) are one of the original five constituent tribes of the League of the Iroquois (Hodenosaunee). Their traditional homeland is in and around Onondaga County, New York. Being centrally located, they were the keepers of the fire in the figurative longhouse, with the Cayuga and Seneca to their west and the Oneida and Mohawk to their east. For this reason, the League of the Iroquois historically met at Onondaga, as indeed the traditional chiefs do today.

In the American Revolutionary War, the Onondaga were at first officially neutral, although individual Onondaga warriors were involved in at least one raid on American settlements. The Onondaga later sided with the majority of the League and fought against the United States in alliance with the British Crown, after an American attack on their main village on April 20, 1779. Many Onondaga therefore followed Joseph Brant to Six Nations, Ontario after the United States was accorded independence. Those remaining in New York are under the government of traditional chiefs nominated by matriarchs, rather than elected.

On November 11, 1794, the Onondaga Nation, along with the other Haudenosaunee nations, signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States.

On March 11, 2005, the Onondaga Nation of Nedrow, New York, filed a land rights action in federal court, seeking acknowledgement of title to over 3,000 square miles of ancestral lands centering on Syracuse, New York, as well as increased influence over environmental restoration efforts at Onondaga Lake and other EPA Superfund sites.

The Oneida (Onayotekaono or the People of the Upright Stone) are a tribe of American Indians and comprise one of the five founding nations of the Iroquois Confederacy.

The Iroquois call themselves Haudenosaunee ("The people of the longhouses") in reference to their communal lifestyle and the construction of their dwellings.

�Originally the Oneida inhabited the area that later became central New York, particularly around Oneida Lake and Oneida County. They broke with the other nations of the Haudenosaunee to side with the United States in the Revolutionary War, in particular aiding George Washington at Valley Forge in 1777. After the war they were displaced by retaliatory and other raids.

In 1794 they, along with other Haudenosaunee nations, signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States. They were granted 6 million acres (24,000 km) of lands, primarily in New York; this was effectively the first Indian reservation in the United States. Subsequent treaties and actions by the State of New York pared this down to 32 acres (0.1 km). In the 1830s many of the Oneida relocated into Canada and Wisconsin, due to the rising tide of Indian Removal.

In 1974 and 1985 the US Supreme Court ruled that the treaties between the State of New York and the Oneida that had deprived them of these lands were illegal. Litigation in these matters is ongoing.

The Kanienkehaka, or Mohawk tribe of Native American people live around Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River in what is now Canada and the United States. Their traditional homeland is further South, in New York State, around present day Albany, New York. They belong to the Iroquois confederation. After the pre-historic formation of the Iroquois confederation (Hodenosaunee), the Mohawks became keepers of the Eastern Door, guarding the members against invasions from that direction.

During the 17th century, the Mohawks became allied with the Dutch at Fort Orange, New Netherland (now Albany, New York). Their Dutch trade partners equipped the Mohawks to fight against other nations allied with the French, including the Ojibwes, Huron-Wendats, and Algonkins. After the fall of New Netherland to the English, the Mohawks became allies of the English Crown. Because of ongoing conflict with Anglo-American settlers infiltrating into the Mohawk Valley and outstanding treaty obligations to the Crown, the Mohawks generally fought against the United States during the American Revolutionary War, the War of the Wabash Confederacy, and the War of 1812. After the Americans' victory, one prominent Mohawk leader, Joseph Brant, led a large group of Iroquois out of New York to a new homeland at Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario.

On November 11, 1794, representatives of the Mohawks (along with the other Haudenosaunee nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States.

One large group of Mohawks, who were expelled by the United States as traitors were given land by the British Governor Craig and imposed to French speaking Quebecois who were refused new land because of not being English. They stayed in the vicinity of Montreal, where they served as the mercenaries of the British army. One of the most famous Catholic Mohawks was Kateri, who was later beatified. From this group descend the Mohawks of Kahnawake, Akwesasne and Kanesatake.

Members of the Mohawk tribe now live in settlements spread throughout New York State and Southeastern Canada. Among these are Ganienkeh and Kanatsiohareke in Northeast New York, Akwesasne/St.Regis along the Ontario-New York State border, Kanesatake/Oka and Kahnawake/Caughnawaga in southwest Quebec, and Tyendinaga and Wahta/Gibson in southern Ontario. Mohawks also form the majority on the mixed Iroquois reserve, Six Nations of the Grand River, in Ontario.

Many Mohawk communities have two sets of chiefs that exist in parallel and are in some sense rivals. One group are the hereditary chiefs nominated by clan matriarchs in the traditional fashion; the other are elected chiefs with whom the Canadian and US governments usually deals exclusively.

Since the 1980s, Mohawk politics have been driven by factional disputes over gambling. Both the elected chiefs and the controversial Warrior Society have encouraged gaming as a means of ensuring tribal self-sufficiency on the various reserves/reservations, while traditional chiefs have opposed gaming on moral grounds and out of fear of corruption and organized crime. Such disputes have also been associated with religious divisions: the traditional chiefs are often associated with the Longhouse tradition, while Warrior Society has attacked that religion in favour of the pre-Longhouse Old tradition.

Meanwhile, the elected chiefs have tended to be associated (though in a much looser and general way) with democratic values. The Government of Canada who ruled the Indians imposed English school and separated families to place children in english boarding school. Mohawks like in other tribes have lost their native language and many left the reserve to mesh with the English Canadian culture.

The Tuscarora are a Native American tribe originally in North Carolina, which moved north to New York, and then partially into Canada.

In 1720 the Tuscarora fled European invasion of North Carolina to New York to become the Sixth nation of the Iroquois, settling near by the Oneidas.

The Tuscarora War of 1711 The first successful and permanent settlement of North Carolina by Europeans began in earnest in 1653. The Tuscarora lived in peace with the European settlers who arrived in North Carolina for over 50 years at a time when nearly every other colony in America was actively involved in some form of conflict with the Native Americans. However, the arrival of the settlers was ultimately disastrous for the original inhabitants of North Carolina.

There were two primary contingents of Tuscarora at this point, a Northern group led by Chief Tom Blunt and a Southern group led by Chief Hancock. Chief Blunt occupied the area around what is present-day Bertie County on the Roanoke River; Chief Hancock was closer to New Bern, occupying the area south of the Pamplico River (now the Pamlico River). While Chief Blunt became close friends with the Blount family of the Bertie region, Chief Hancock found his villages raided and his people frequently kidnapped and sold into slavery. Both groups were heavily impacted by the introduction of European diseases, and both were rapidly having their lands stolen by the encroaching settlers. Ultimately, Chief Hancock felt there was no alternative but to attack the settlers. Tom Blunt did not become involved in the war at this point.

The Southern Tuscarora, led by Chief Hancock, worked in conjunction with the Pamplico Indians, the Cothechneys, the Cores, the Mattamuskeets and the Matchepungoes to attack the settlers in a wide range of locations in a short time period. Principle targets were the planters on the Roanoke River, the planters on the Neuse and Trent Rivers and the city of Bath. The first attacks began on September 22nd, 1711, and hundreds of settlers were ultimately killed. Several key political figures were either killed or driven off in the subsequent months.

Governor Edward Hyde called out the militia of North Carolina, and secured the assistance of the Legislature of South Carolina, who provided "six hundred militia and three hundred and sixty Indians under Col. Barnwell". This force attacked the Southern Tuscarora and other tribes in Craven County at Fort Narhantes on the banks of the Neuse River in 1712. The Tuscarora were "defeated with great slaughter; more than three hundred savages were killed, and one hundred made prisoners." These prisoners were largely women and children, who were ultimately sold into slavery.

Chief Blunt was then offered the chance to control the entire Tuscarora tribe if he assisted the settlers in putting down Chief Hancock. Chief Blunt was able to capture Chief Hancock, and the settlers executed him in 1712. In 1713 the Southern Tuscaroras lost Fort Neoheroka, with 900 killed or captured.

It was at this point that the majority of the Southern Tuscarora began migrating to New York to escape the settlers in North Carolina.

�The remaining Tuscarora signed a treaty with the settlers in June 1718 granting them a tract of land on the Roanoke River in what is now Bertie County. This was the area already occupied by Tom Blunt, and was specified as 56,000 acres (227 km); Tom Blunt, who had taken on the name Blount, was now recognized by the Legislature of North Carolina as King Tom Blount. The remaining Southern Tuscarora were removed from their homes on the Pamlico River and made to move to Bertie.

In 1722 Bertie County was chartered, and over the next several decades the remaining Tuscorara lands were continually diminished as they were sold off in deals that were frequently designed to take advantage of the Native Americans.

A substantial portion of the Tuscaroras sided with the Oneida nation against the rest of the League of the Six Nations by fighting for the United States government during the American Revolutionary War. Those that remained allies of the British Crown would later follow Joseph Brant into Ontario.

In 1803 the final contingent of the Tuscarora migrated to New York to join the tribe at their reservation in Niagara County, under a treaty directed by Thomas Jefferson. In 1831 the Tuscarora sold the remaining rights to their lands in North Carolina. By this point the 56,000 acres had been pared down to a mere 2000 acres.

Skarure, the Tuscarora language is from the southern group of the Iroquoian languages.

Iroquois Clans include: Wolf, Bear, Turtle, Snipe, Deer, Beaver, Heron, Hawk

Members of the League speak Iroquoian languages that are distinctly different from those of other Iroquoian speakers. This suggests that while the different Iroquoian tribes had a common historical and cultural origin, they diverged as peoples over a sufficiently long time that their languages (and cultures) became different, and they distinguished themselves as different peoples. Archaeological evidence shows that Iroquois ancestors lived in the Finger Lakes region from at least 1000.

After becoming united in the League, the Iroquois invaded the Ohio River Valley in present-day Kentucky to seek additional hunting grounds. According to one theory of pre-contact history, the Haudenosaunee by about 1200 pushed tribes of the Ohio River valley, such as the Quapaw (Akansea) and Ofo (Mosopelea), out of the region in a migration west of the Mississippi River. But, Robert La Salle listed the Mosopelea among the Ohio Valley peoples defeated by the Iroquois in the early 1670s, during the later Beaver Wars. By 1673, the Siouan-speaking groups had settled in the Midwest, establishing what became known as their historical territories. Just as the Siouan peoples were displaced by the Iroquois, they displaced less powerful tribes whom they encountered west of the Mississippi, such as the Osage, who moved further west.

The Iroquois League was established prior to major European contact. Most archaeologists and anthropologists believe that the League was formed sometime between about 1450 and 1600. A few claims have been made for an earlier date; one recent study has argued that the League was formed shortly after a solar eclipse on August 31, 1142, an occurrence which seemed to be related to oral tradition about the League's origins. Anthropologist Dean Snow argues that the archaeological evidence does not support a date earlier than 1450, and that recent claims for a much earlier date "may be for contemporary political purposes".

According to tradition, the League was formed through the efforts of two men, Dekanawida, sometimes known as the Great Peacemaker, and Hiawatha. They brought a message, known as the Great Law of Peace, to the squabbling Iroquoian nations. The nations who joined the League were the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga and Seneca,. Once they ceased most of their infighting, the Iroquois rapidly became one of the strongest forces in 17th- and 18th-century northeastern North America.

Hiawatha (also known as Ayenwatha, Aiionwatha, or Haien'wa'tha; Onondaga) is legendary Native American leader and founder of the Iroquois confederacy. Depending on the version of the narrative, Hiawatha lived in the 16th century and was a leader of the Onondaga or the Mohawk.

Hiawatha was a follower of The Great Peacemaker, a prophet and spiritual leader, who proposed the unification of the Iroquois peoples, who shared similar languages. Hiawatha, a skilled and charismatic orator, was instrumental in persuading the Senecas, Cayugas, Onondagas, Oneidas, and Mohawks, to accept the Great Peacemaker's vision and band together to become the Five Nations of the Iroquois confederacy. Later, the Tuscarora nation joined the Confederacy to become the Sixth Nation.

According to legend, an evil Onondaga chieftain named Tadodaho was the last to be converted to the ways of peace by The Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha. He became the spiritual leader of the Haudenosaunee. This is said to have occurred at Onondaga Lake near Syracuse, New York. The title Tadodaho is still used for the league's spiritual leader, the fiftieth chief, who sits with the Onondaga in council. He is the only one of the fifty to have been chosen by the entire Haudenosaunee people. The current Tadodaho is Sid Hill of the Onondaga Nation.

Ancient pottery reveals insights on Iroquoian population's power in 16th century PhysOrg - August 9, 2017

An innovative study demonstrates how decorations on ancient pottery can be used to discover new evidence for how groups interacted across large regions. The research sheds new light on the importance of a little-understood Iroquoian population in upstate New York and its impact on relations between two emerging Native American political powers in the 16th century.

In Reflections in Bullough's Pond, historian Diana Muir argues that the pre-contact Iroquois were an imperialist, expansionist culture whose use of the corn/beans/squash agricultural complex enabled them to support a large population. They made war against Algonquian peoples. Muir uses archaeological data to argue that the Iroquois expansion onto Algonquian lands was checked by the Algonquian adoption of agriculture. This enabled them to support their own populations large enough to have sufficient warriors to defend against the threat of Iroquois conquest.

The Iroquois may be the Kwedech described in the oral legends of the Mi'kmaq nation of Eastern Canada. These legends relate that the Mi'kmaq in the late pre-contact period had gradually driven their enemies - the Kwedech - westward across New Brunswick, and finally out of the Lower St. Lawrence River region. The Mi'kmaq named the last-conquered land "Gespedeg" or "lost land," leading to the French word Gaspe. The "Kwedech" are generally considered to have been Iroquois, specifically the Mohawk; their expulsion from Gaspe by the Mi'kmaq has been estimated as occurring ca. 1535-1600.

Around 1535, Jacques Cartier reported Iroquoian-speaking groups on the Gaspe peninsula and along the St. Lawrence River. Archeologists and anthropologists have defined the St. Lawrence Iroquoians as a distinct and separate group (and possibly several discrete groups), living in the villages of Hochelaga and others nearby (near present-day Montreal), which had been visited by Cartier. By 1608, when Samuel de Champlain visited the area, that part of the St. Lawrence River valley had no settlements, but was controlled by the Mohawk as a hunting ground. On the Gaspe peninsula, Champlain encountered Algonquian-speaking groups. The precise identity of any of these groups continues to be debated.

The Iroquois became well known in the south by this time. After the first English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia (1607), numerous 17th-century accounts describe a powerful people known to the Powhatan Confederacy as the Massawomeck, and to the French as the Antouhonoron. They were said to come from the north, beyond the Susquehannock territory. Historians have often identified the Massawomeck / Antouhonoron as the Iroquois proper. Other Iroquoian candidates include the Erie, who were destroyed by the Iroquois in 1654 over competition for the fur trade. Over the years 1670-1710, the Five Nations achieved political dominance of most of Virginia west of the fall line and extending to the Ohio River valley in present-day West Virginia. They reserved it as a hunting ground by right of conquest and continued to claim it until 1722, when they began selling land in the area to their British allies.

Beginning in 1609, the League engaged in the Beaver Wars with the French and their Iroquoian-speaking Huron allies. They also put great pressure on the Algonquian peoples of the Atlantic coast and the boreal Canadian Shield region, and not infrequently fought the English colonies as well. During the 17th century, they were said to have exterminated the Neutral Nation.and Erie Tribe to the west. The wars were a way to control the lucrative fur trade, although additional reasons are often given for these wars.

In 1628, the Mohawk defeated the Mahican to gain a monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch at Fort Orange, New Netherland. The Mohawk would not allow Canadian Indians to trade with the Dutch. In 1645, a tentative peace was forged between the Iroquois and the Hurons, Algonquins and French.

In 1646, Jesuit missionaries at Sainte-Marie among the Hurons went as envoys to the Mohawk lands to protect the fragile peace of the time. Mohawk attitudes toward the peace soured while the Jesuits' were traveling and the party was attacked by Mohawk warriors en route. The missionaries were taken to the village of Ossernenon (Auriesville, N.Y.), where the moderate Turtle and Wolf clans recommended setting the priests free. Angered, members of the Bear clan killed Jean de Lalande and Isaac Jogues on October 18, 1646. The Catholic Church has commemorated the two French priests as among the eight North American Martyrs. In 1649 during the Beaver Wars, the Iroquois used recently purchased Dutch guns to attack the Hurons. From 1651 to 1652, the Iroquois attacked the Susquehannocks, without sustained success.

In the early 17th century, the Iroquois were at the height of their power, with a population of about 12,000 people.[27] In 1654, they invited the French to establish a trading and missionary settlement at Onondaga (in present-day New York state). The following year, the Mohawk attacked and expelled the French from the trading post, possibly because of the sudden death of 500 Indians from an epidemic of smallpox, a European infectious disease to which they had no immunity.

From 1658 to 1663, the Iroquois were at war with the Susquehannock and their Delaware and Province of Maryland allies. In 1663, a large Iroquois invasion force was defeated at the Susquehannock main fort. In 1663, the Iroquois were at war with the Sokoki tribe of the upper Connecticut River. Smallpox struck again; and through the effects of disease, famine and war, the Iroquois were threatened by extermination. In 1664, an Oneida party struck at allies of the Susquehannock on Chesapeake Bay.

In 1665, three of the Five Nations made peace with the French. The following year, the Canadian Governor sent the Carignan regiment under Marquis de Tracy to confront the Mohawk and the Oneida. The Mohawk avoided battle, but the French burned their villages and crops. In 1667, the remaining two Iroquois Nations signed a peace treaty with the French and agreed to allow their missionaries to visit their villages. This treaty lasted for 17 years.

Around 1670, the Iroquois drove the Siouan Mannahoac tribe out of the northern Virginia Piedmont region. They began to claim ownership of the territory by right of conquest. In 1672, the Iroquois were defeated by a war party of Susquehannock.

Some old histories state that the Iroquois defeated the Susquehannock during this time period. As no record of a defeat has been found, historians have concluded that no defeat occurred.

In 1677, the Iroquois adopted the majority of the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannock into their nation.

By 1677, the Iroquois formed an alliance with the English through an agreement known as the Covenant Chain. Together, they battled to a standstill the French, who were allied with the Huron. These Iroquoian people had been a traditional and historic foe of the Confederacy. The Iroquois colonized the northern shore of Lake Ontario and sent raiding parties westward all the way to Illinois Country. The tribes of Illinois were eventually defeated, not by the Iroquois, but rather by the Potawatomis.

In 1684, the Iroquois invaded Virginia and Illinois territory again, and unsuccessfully attacked French outposts in the latter. Later that year, the Virginia Colony agreed at Albany to recognize the Iroquois' right to use the North-South path running east of the Blue Ridge (later the Old Carolina Road), provided they did not intrude on the English settlements east of the fall line.

In 1679, the Susquehannock, with Iroquois help, attacked Maryland's Piscataway and Mattawoman allies. Peace was not reached until 1685.

With support from the French, the Algonquian nations drove the Iroquois out of the territories north of Lake Erie and west of present-day Cleveland, regions which they had conquered during the Beaver Wars.

In 1687, Jacques-Rene de Brisay de Denonville, Marquis de Denonville, Governor of New France from 1685 to 1689, set out for Fort Frontenac with a well-organized force. There they met with the 50 hereditary sachems of the Iroquois Confederation from the Onondaga council fire, who came under a flag of truce. Denonville recaptured the fort for New France and seized, chained, and shipped the 50 Iroquois chiefs to Marseilles, France, to be used as galley slaves. He ravaged the land of the Seneca, landing a French armada at Irondequoit Bay, striking straight into the seat of Seneca power, and destroying many of its villages. Fleeing before the attack, the Seneca moved further west, east and south down the Susquehanna River. Although great damage was done to the Seneca home land, the Seneca's military might was not appreciably weakened. The Confederacy and the Seneca moved into an alliance with the British in the east; the destruction of the Seneca land infuriated the Iroquois Confederacy.

On August 4, 1689, they retaliated by burning to the ground Lachine, a small town adjacent to Montreal. Fifteen hundred Iroquois warriors had been harassing Montreal defenses for many months prior to that. They finally exhausted and defeated Denonville and his forces. His tenure was followed by the return of Frontenac, who succeeded Denonville as Governor for the next nine years (1689-1698). Frontenac had been arranging a new plan of attack to lessen the effects of the Iroquois in North America. Realizing the danger of holding the sachems, he located the 13 surviving leaders and returned with them to New France that October 1698.

During King William's War (North American part of the War of the Grand Alliance), the Iroquois were allied with the English. In July 1701, they concluded the "Nanfan Treaty", deeding the English a large tract north of the Ohio River. The Iroquois claimed to have conquered this territory 80 years earlier. France did not recognize the validity of the treaty, as it had the strongest presence of colonists within the area in question. Meanwhile, the Iroquois were negotiating peace with the French; together they signed the Great Peace of Montreal that same year.

After the 1701 peace treaty with the French, the Iroquois remained mostly neutral even though during Queen Anne's War (North American part of the War of the Spanish Succession) they were involved in some planned attacks against the French. Peter Schuyler, mayor of Albany, arranged for three Mohawk chiefs and a Mahican chief (the Four Mohawk Kings) to travel to London in 1710 to meet with Queen Anne in an effort to seal an alliance with the British. Queen Anne was so impressed by her visitors that she commissioned their portraits by court painter John Verelst. The portraits are believed to be some of the earliest surviving oil portraits of Aboriginal peoples taken from life.

In the first quarter of the 18th century, the Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora fled north from the pressure of British colonization of North Carolina and intertribal warfare. They petitioned to become the sixth nation of the Confederacy. This was a non-voting position but placed them under the protection of the Haudenosaunee.

In 1721 and 1722, Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia concluded a new Treaty at Albany with the Iroquois, renewing the Covenant Chain and agreeing to recognize the Blue Ridge as the demarcation between Virginia Colony and the Iroquois. But, as European settlers began to move beyond the Blue Ridge and into the Shenandoah Valley in the 1730s, the Iroquois objected. Virginia officials told them that the demarcation was to prevent the Iroquois from trespassing east of the Blue Ridge, but it did not prevent English from expanding west of them. The Iroquois were on the verge of going to war with the Virginia Colony, when in 1743, Governor Gooch paid them the sum of 100 pounds sterling for any settled land in the Valley that was claimed by the Iroquois. The following year at the Treaty of Lancaster, the Iroquois sold Virginia all their remaining claims on the Shenandoah Valley for 200 pounds in gold.

During the French and Indian War (North American part of the Seven Years' War), the Iroquois sided with the British against the French and their Algonquian allies, both traditional enemies of the Iroquois. The Iroquois hoped that aiding the British would also bring favors after the war. Few Iroquois warriors joined the campaign. In the Battle of Lake George, a group of Catholic Mohawk (from Kahnawake) and French ambushed a Mohawk-led British column.

After the war, to protect their alliance, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding white settlements beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Colonists largely ignored the order and the British had insufficient soldiers to enforce it. The Iroquois agreed to adjust the line again at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768), whereby they sold the British Crown all their remaining claim to the lands between the Ohio and Tennessee rivers.

During the American Revolution, the Iroquois first tried to stay neutral. Pressed to join one side or the other, many Tuscarora and the Oneida sided with the colonists, while the Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga and Cayuga remained loyal to Great Britain, with whom they had stronger relationships. It was the first political split among the Six Nations. Joseph Louis Cook offered his services to the United States and received a Congressional commission as a Lieutenant Colonel- the highest rank held by any Native American during the war.

The Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant, other war chiefs, and British allies conducted numerous operations against frontier settlements in the Mohawk Valley, destroying many villages and crops. The Continentals retaliated and in 1779, George Washington ordered the Sullivan Campaign, led by Col. Daniel Brodhead and General John Sullivan, against the Iroquois nations to "not merely overrun, but destroy," the British-Indian alliance. They burned many Iroquois villages and stores throughout western New York; refugees moved north to Canada. By the end of the war, few houses and barns in the valley had survived the warfare.

After the war, the ancient central fireplace of the League was reestablished at Buffalo Creek. Captain Joseph Brant and a group of Iroquois left New York to settle in Quebec (present-day Ontario). As a reward for their loyalty to the British Crown, they were given a large land grant on the Grand River. Brant's crossing of the river gave the original name to the area: Brant's ford. By 1847, European settlers began to settle nearby and named the village Brantford. The original Mohawk settlement was on the south edge of the present-day city at a location still favorable for launching and landing canoes. In the 1830s many of the Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, Cayuga and Tuscarora relocated into the Indian Territory, the Province of Upper Canada and Wisconsin.

The Iroquois are a melting pot. League traditions allowed for the dead to be symbolically replaced through captives taken in the "Mourning War." Raids were conducted to take vengeance on enemies and to seize captives to replace lost compatriots. This tradition was common to native people of the northeast and was quite different from European settlers' notions of combat. The captives were generally adopted by families of the tribes to replace members who had died.

The Iroquois worked to incorporate conquered peoples and assimilate them as Iroquois, thus naturalizing them as full citizens of the tribe. Cadwallader Colden wrote, "It has been a constant maxim with the Five Nations, to save children and young men of the people they conquer, to adopt them into their own Nation, and to educate them as their own children, without distinction; These young people soon forget their own country and nation and by this policy the Five Nations make up the losses which their nation suffers by the people they lose in war."

By 1668, two-thirds of the Oneida village were assimilated Algonquians and Hurons. At Onondaga there were Native Americans of seven different nations and among the Seneca eleven. They also adopted European captives, as did the Catholic Mohawk in settlements outside Montreal.

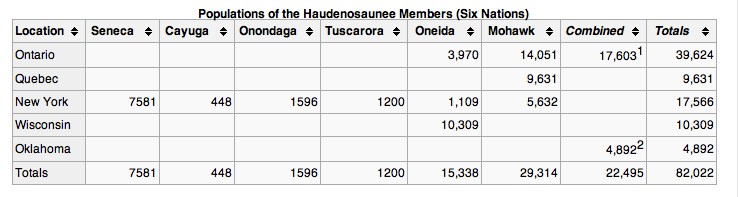

The total number of Iroquois today is difficult to establish. About 45,000 Iroquois lived in Canada in 1995. In the 2000 census, 80,822 people in the United States claimed Iroquois ethnicity, with 45,217 of them claiming only Iroquois background. Tribal registrations among the Six Nations in the United States in 1995 numbered about 30,000 in total.

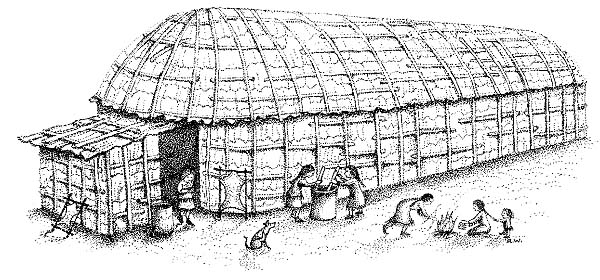

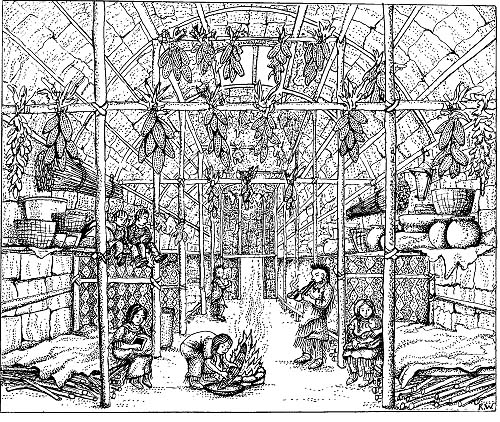

The Iroquois people lived in villages of longhouses, which were large wood-frame buildings covered with sheets of elm bark. Iroquois longhouses were up to a hundred feet long, and each one housed an entire clan (as many as 60 people.) Here are some pictures of Indian longhouses like the ones Iroquois Indians used, and a drawing of what a longhouse looked like on the inside. Today, Iroquois families live in modern houses and apartment buildings, just like you.

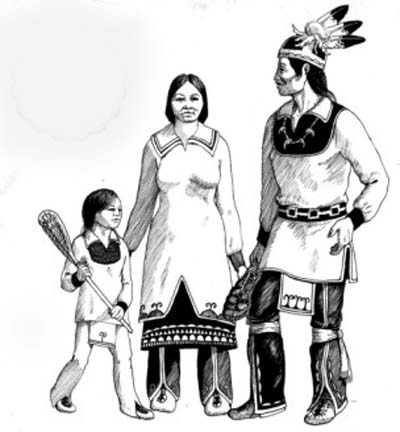

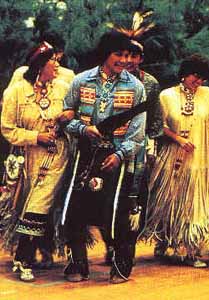

Iroquois men wore breechcloths with long leggings. Iroquois women wore wraparound skirts with shorter leggings. Men did not originally wear shirts in Iroquois culture, but women often wore a tunic called an overdress. Iroquois people also wore moccasins on their feet and heavy robes in winter. In colonial times, the Iroquois adapted European costume like long cloth shirts, decorating them with fancy beadwork and ribbon applique. Here is a webpage about traditional Iroquois dress, and here are some photographs and links about American Indian clothes in general.

The Iroquois didn't wear long headdresses like the Sioux. Iroquois men wore a gustoweh, which was a feathered cap with different insignia for each tribe (the headdress worn by the man in this picture has three eagle feathers, showing that he is Mohawk.) Iroquois women sometimes wore special beaded tiaras. Iroquois warriors often shaved their heads except for a scalplock or a crest down the center of their head (the style known as a roach, or a "Mohawk.")

Sometimes they augmented this hairstyle with splayed feathers or artificial roaches made of brightly dyed porcupine and deer hair. Here are some pictures of these different kinds of American Indian headdresses. Iroquois Indian women only cut their hair when they were in mourning, wearing it long and loose or plaited into a long braid. Men sometimes decorated their faces and bodies with tribal tattoos, but Iroquois women generally didn't paint or tattoo themselves.

Today, some Iroquois people still wear moccasins or a beaded shirt, but they wear modern clothes like jeans instead of breechcloths... and they only wear feathers in their hair on special occasions like a dance.

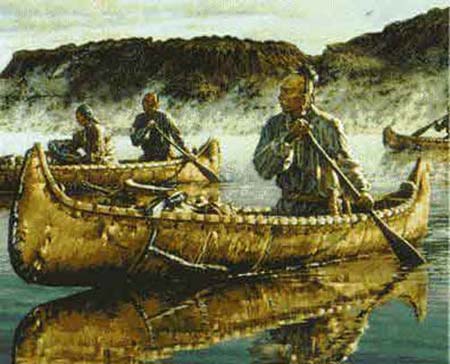

The Iroquois used elm-bark or dugout canoes for fishing trips, but usually preferred to travel by land. Originally the Iroquois tribes used dogs as pack animals. There were no horses in North America until colonists brought them over from Europe. In wintertime, Iroquois people used laced snowshoes and sleds to travel through the snow.

Iroquois hunters used bows and arrows. Iroquois fishermen generally used spears and fishing poles. In war, Iroquois men used their bows and arrows or fought with clubs, spears and shields.

Other important tools used by the Iroquois Indians included stone adzes (hand axes for woodworking), flint knives for skinning animals, and wooden hoes for farming. The Iroquois were skilled woodworkers, steaming wood so they could bend it into curved tools. Some Iroquois people still make lacrosse sticks this way today.

The Iroquois were a mix of farmers, fishers, gatherers and hunters, though their main diet came from farming. The main crops they farmed were corn, beans and squash, which were called the three sisters and were considered special gifts from the Creator. These crops are grown strategically. The cornstalks grow, the bean plants climb the stalks, and the squash grow beneath, inhibiting weeds and keeping the soil moist under the shade of their broad leaves. In this combination, the soil remained fertile for several decades. The food was stored during the winter, and it lasted for two to three years. When the soil eventually lost its fertility, the Iroquois migrated.

Gathering was the job of the women and children. Wild roots, greens, berries and nuts were gathered in the summer. During spring, maple syrup was tapped from the trees, and herbs were gathered for medicine.

The Iroquois hunted mostly deer but also other game such as wild turkey and migratory birds. Muskrat and beaver were hunted during the winter. Fishing was also a significant source of food because the Iroquois were located near a large river (St. Lawrence River). They fished salmon, trout, bass, perch and whitefish. In the spring the Iroquois netted, and in the winter fishing holes were made in the ice.

When Americans and Canadians of European descent began to study Iroquois customs in the 18th and 19th centuries, they learned that the people had a matrilineal system: women held property and hereditary leadership passed through their lines. They held dwellings, horses and farmed land, and a woman's property before marriage stayed in her possession without being mixed with that of her husband. They had separate roles but real power in the nations. The work of a woman's hands was hers to do with as she saw fit. At marriage, a young couple lived in the longhouse of the wife's family.

A woman choosing to divorce a shiftless or otherwise unsatisfactory husband was able to ask him to leave the dwelling and take his possessions with him. The children of the marriage belonged to their mother's clan and gained their social status through hers. Her brothers were important teachers and mentors to the children, especially introducing boys to men's roles and societies. The clans were matrilineal, that is, clan ties were traced through the mother's line. If a couple separated, the woman kept the children. The chief of a clan could be removed at any time by a council of the women elders of that clan. The chief's sister was responsible for nominating his successor.

The Iroquois believe that the spirits change the seasons. Key festivals coincided with the major events of the agricultural calendar, including a harvest festival of thanksgiving. The Great Peacemaker (Deganawida) was their prophet. After the arrival of the Europeans, many Iroquois became Christians, among them Kateri Tekakwitha, a young woman of Mohawk-Algonkin parents. Traditional religion was revived to some extent in the second half of the 18th century by the teachings of the Iroquois prophet Handsome Lake.

The two most important Iroquois instruments are drums and flutes. Iroquois drums were often filled with water to give them a distinctive sound different from the drums of other tribes. Most Iroquois music is very rhythmic and consists mostly of drumming and lively singing. Flutes were used to woo women in the Iroquois tribes. An Iroquois Indian man would play beautiful flute music outside his girlfriend's longhouse at night to show her he was thinking about her.

The Iroquois tribes were known for their mask carving, which is considered such a sacred art form that outsiders are still not permitted to view many of these masks. Beadwork and the more demanding porcupine quillwork are more common Iroquois crafts. The Iroquois Indians also crafted wampum out of white and purple shell beads. Wampum beads were traded as a kind of currency, but they were more culturally important as an art material. The designs and pictures on Iroquois wampum belts often told a story or represented a person's family.

Iroquois Council of Chiefs had declared all Iroquois false face masks to be sacred objects whose images should not be disseminated among non-Indians. They also called for the return of all masks from museums and other collections, claiming that the misuse and distribution of these objects interfered with traditional Iroquois medicine practices.

The tribes of the Iroquois' League of the Six Nations (Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, Cayuga, Mohawk, and Tuscarora) have been united for centuries in their celebration of great festivals, at which occur numerous ceremonies of significance to both the spiritual and physical life of the tribes. Sacred ceremonies include feather dances, drum dances, the rite of personal chant, the bowl game, and Sun ceremonies.

Hiawatha (also known as Ha-yo-went'-ha) who lived around 1550, was variously a leader of the Onondaga and Mohawk nations of Native Americans.

Hiawatha was a follower of Deganawidah, a prophet and shaman who was credited as the founder of the Iroquois confederacy, (referred to as Haudenosaune by the people). If Deganawidah was the man of ideas, Hiawatha was the politician who actually put the plan into practice. Hiawatha was a skilled and charismatic orator, and was instrumental in persuading the Iroquois peoples, the Senecas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Cayugas, and Mohawks, a group of Native Americans who shared a common language, to accept Deganawidah's vision and band together to become the Five Nations of the Iroquois confederacy. (Later, in 1721, the Tuscarora nation joined the Iroquois confederacy, and they became the Six Nations).

According to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha is based on Schoolcraft's Algic Researches and History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Schoolcraft seems to have based his "Hiawatha" primarily on the Algonquian trickster-figure Manabozho. There is none, or only faint resemblance between Longfellow's hero and the life-stories of Hiawatha and Deganawidah; see Longfellow's Hiawatha vs. the historical Iroquois Hiawatha.

Those who joined in the League were the Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga and Mohawks. Once they ceased (most) infighting, they rapidly became one of the strongest forces in 17th and 18th century northeastern North America. The League engaged in a series of wars against the French and their Iroquoian-speaking Wyandot ("Huron") allies. They also put great pressure on the Algonquian peoples of the Atlantic coast and what is now subarctic Canada and not infrequently fought the English colonies as well.

According to Francis Parkman, the Iroquois at the 17th century height of their power had a population of around 12,000 people. League traditions allowed for the dead to be symbolically replaced through the "Mourning War", raids intended to seize captives and take vengeance on non-members. This tradition was common to native people of the northeast and was quite different from European settlers' notions of combat.

In 1720 the Tuscarora fled north from the European colonization of North Carolina and petitioned to become the Sixth Nation. This is a non-voting position but places them under the protection of the Confederacy.

In 1794, the Confederacy entered into the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States.