The term Indus script (also Harappan script) refers to short strings of symbols associated with the Indus Valley Civilization, in use during the Mature Harappan period, between the 26th and 20th centuries BC. In spite of many attempts at decipherments and claims, it is as yet undeciphered. The underlying language is unknown, and the lack of a bilingual makes the decipherment unlikely pending significant new finds.

The first publication of a Harappan seal dates to 1873, in the form of a drawing by Alexander Cunningham. Since then, well over 4000 symbol-bearing objects have been discovered, some as far afield as Mesopotamia. In early seventies Iravatham Mahadevan published a corpus and concordance of Harrapan writing listing about 3700 seals and about 417 distinct sign in specific patterns. The average size of writing is five signs and largest text in a single line is 14 signs. He also established the direction of writing as right to left.

Some early scholars, starting with Cunningham in 1877, thought that the script was the archetype of the Brahmi script used by Ashoka. Cunningham's ideas were supported by G.R. Hunter, Iravatham Mahadevan and a minority of scholars continue to argue for the Indus script as the predecessor of the Brahmic family. However most scholars disagree, claiming instead that the Brahmi script derived from the Aramaic script.

Early Harappan: The script generally refers to that used in the mature Harappan phase, which perhaps evolved from a few signs found in early Harappa after 3500 BC. However, the early date and the interpretation given in the BBC report have been challenged by the long-term excavator of Harappa, Richard Meadow] The use of early pottery marks and incipient Indus signs was followed by the mature Harappan script.

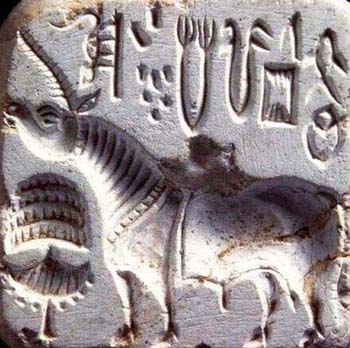

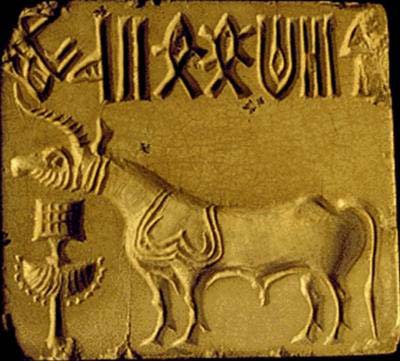

Mature Harappan: The Harappan signs are most commonly associated with flat, rectangular stone tablets called seals, but they are also found on at least a dozen other materials.

Late Harappan: After 1900 BC, the systematic use of the symbols ended, after the final stage of the Mature Harappan civilization.

A few Harappan signs have been claimed to appear until as late as around 1100 BC (the beginning of the Indian Iron Age). Onshore explorations near Bet Dwarka in Gujarat revealed the presence of late Indus seals depicting a 3-headed animal, earthen vessel inscribed in what is claimed to be a late Harappan script, and a large quantity of pottery similar to Lustrous Red Ware bowl and Red Ware dishes, dish-on-stand, perforated jar and incurved bowls which are datable to the 16th century BC in Dwarka, Rangpur and Prabhas.

The thermoluminescence date for the pottery in Bet Dwaraka is 1528 BC. This evidence has been used to claim that a late Harappan script was used until around 1500 BC. [2] Other excavations in India at Vaisali, Bihar and Mayiladuthurai, Tamil Nadu have been claimed to contain Indus symbols being used as late as 1100 BC.

In May 2007, the Tamil Nadu Archaeological Department found pots with arrow-head symbols during an excavation in Melaperumpallam near Poompuhar. These symbols are claimed to have a striking resemblance to seals unearthed in Mohenjodaro in the 1920s.

In 1960, B.B. Lal of the Archaeological Survey of India wrote a paper in the journal Ancient India. It carried a photograhic catalog of megalithic and chalcolithic pottery which Lal compares with the Ancient Indus script.

Ancient inscriptions that are claimed to bear a striking resemblance to those found in Indus Valley sites have been found in Sanur near Tindivanam in Tamil Nadu, Musiri in Kerala and Sulur near Coimbatore. Indus Script

Script Characteristics

The writing system is intensely pictorial. The script is written from right to left, and sometimes follows a boustrophedonic style. Since the number of principal signs is about 400-600, midway between typical logographic and syllabic scripts, many scholars accept the script to be logo-syllabic (typically syllabic scripts have about 50-100 signs whereas logographic scripts have a very large number of principal signs). Several scholars maintain that structural analysis indicates an agglutinative language underneath the script. However, this is contradicted by the occurrence of signs supposedly representing prefixes and infixes.

Over the years, numerous decipherments have been proposed, but none has been accepted by the scientific community at large. The following factors are usually regarded as the biggest obstacles for a successful decipherment:

The Russian scholar Yuri Knorozov, who has edited a multi-volumed corpus of the inscriptions, surmises that the symbols represent a logosyllabic script, with an underlying Dravidian language as the most likely linguistic substrate.[9] Knorozov is perhaps best known for his decisive contributions towards the decipherment of the Maya script, a pre-Columbian writing system of the Mesoamerican Maya civilization. Knorozov's investigations were the first to conclusively demonstrate that the Maya script was logosyllabic in character, an interpretation now confirmed in the subsequent decades of Mayanist epigraphic research.

The Finnish scholar Asko Parpola repeated several of these suggested Indus script readings. The discovery in Tamil Nadu of a late Neolithic (early 2nd millennium BC, i.e. post-dating Harappan decline) stone celt adorned with Indus script markings has been considered to be significant for this identification. However, their identification as Indus signs has been disputed.

If the Indus signs are purely ideographical, they may contain no information about the underlying language spoken by their creators, i.e., they would be just logographic script, or pictograms.

In 2004, Steve Farmer, an independent scholar, computational linguist Richard Sproat and Indologist Michael Witzel published an article asserting that the Indus Script symbols were not coupled to oral language. Witzel had earlier presented his "Para-Munda" Hypothesis, that the spoken language of the northern Indus civilization was distantly related to the Austro-Asiatic family, though not identical with Proto-Munda (Witzel 1999).

In their 2004 article, Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel present a number of arguments in support of their thesis that the Indus script is nonlinguistic, principal among them being the extreme brevity of the inscriptions, the existence of too many rare signs increasing over the 700 year period of the Mature Harappan civilization, and the lack of random-looking sign repetition typical for representations of actual spoken language (whether syllabic-based or letter-based), as seen, for example, in Egyptian cartouches.

Asko Parpola, critically reviewing the thesis in 2005, opines that these arguments "can be easily controverted".[17] He cites the presence of a large number of rare signs in Chinese, and emphasizes that there is "little reason for sign repetition in short seal texts written in an early logo-syllabic script". He notes that Sproat, "the computer linguist of the Farmer team" agreed in a personal communication that by plain statistical tests such as the distribution of sign frequencies and plain reoccurrences, it is not possible to prove or disprove that the signs represent writing. The latter point, however, was already clearly made in the original Farmer-Sproat-Witzel paper of 2004: "Statistical regularities in sign positions show up in nearly all symbol systems, not just those that encode speech." (cf. also Sproat and Farmer, in: CSLI Studies in Computational Linguistics, Stanford University, 2006, p.10)

Revisiting the question in a 2007 lecture [20], Parpola takes on each of what he considers the 10 main arguments of Farmer and his colleagues, presenting what he considers to be counterarguments for each. He states that "even short noun phrases and incomplete sentences qualify as full writing if the script uses the rebus principle to phonetize some of its signs". He gives the example of "rebus-punning" in the protoliterate phase of Sumerian and Egyptian writing in the 32nd to 31st centuries BC, citing the Narmer Palette as a good example of what is "already a writing system even if the texts are on average shorter than the Indus texts!" However, at the Kyoto conference in May 2009 he said that he now regards the Indus signs as a proto-script, in part due to the Farmer et al. papers.

Joining the debate in a newspaper article, Iravatham Mahadevan has called the Indus "non-script" a non-issue, listing a variety of archaeological and linguistic arguments in support of his thesis.

In an article entitled "The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel", Massimo Vidale opines, based a detailed evaluation of the archaeological context, why he thinks "their thesis is not acceptable."

However, Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel have responded to their critics in a paper entitled "The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis, Five Years Later: Massive Nonliterate Urban Civilizations of Ancient Eurasia," at a large Indus conference in Kyoto, Japan, on May 29-31, 2009; see pdf: .

They opine that Vidale's paper "like others in its class" is polemical in nature, badly distorted the long list of arguments in Farmer et al. 2004, and did not in fact discuss even a single Indus inscription -- despite the fact that the 2004 paper was based on detailed analysis of the Indus corpus.

The new Kyoto paper also promises that its final version will discuss all other critiques by "traditional script adherents" in detail and present a general FAQ on developments in the field in the past five years. As announced at Kyoto, this paper will be jointly published in full early in 2010 by Harvard Oriental Series (Opera Minora) and the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (Kyoto).

A computational study conducted by a joint Indo-US team led by Rajesh P N Rao of University of Washington, consisting of Iravatham Mahadevan and others from Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, was published in April 2009 in Science.[25] They conclude that "given the prior evidence for syntactic structure in the Indus script, (their) results increase the probability that the script represents language".

At the Kyoto Indus conference of May 2009, new data presented by Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel, (and again by Sproat at a conference in Singapore in early August), suggest that the entire methodology of so-called conditional entropy cannot even identify languages in the same language family, let alone nonlinguistic from linguistic symbols; see pdf:

However, speaking on the issue of whether language families can be identified using conditional entropy, Rao and colleagues already state in their Science paper that “answering the question of linguistic affinity of the Indus texts requires a more sophisticated approach, such as statistically inferring an underlying grammar for the Indus texts from available data and comparing the inferred rules with those of various known language families.

This Indus seal depicts a nude male deity with three faces (tri-murti, Brahama god), seated in lotus position on a throne, perhaps wearing bangles on both arms and an elaborate headdress. Five symbols of the Indus script appear on either side of the headdress which is made of two outward projecting buffalo style curved horns, with two upward projecting points.

A single branch with three pipal (hindu/bhartiya pious tree) leaves rises from the middle of the headdress. The feet of the throne are carved with the hoof of a bovine as is seen on the bull and unicorn seals. The seal may not have been fired, but the stone is very hard. A grooved and perforated boss is present on the back of the seal. Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050 Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.296 Mackay 1938: 335, pl. LXXXVII, 222

Computers unlock more secrets of the mysterious Indus Valley script PhysOrg - August 4, 2009

Four-thousand years ago, an urban civilization lived and traded on what is now the border between Pakistan and India. During the past century, thousands of artifacts bearing hieroglyphics left by this prehistoric people have been discovered. Today, a team of Indian and American researchers are using mathematics and computer science to try to piece together information about the still-unknown script.

The team led by a University of Washington researcher has used computers to extract patterns in ancient Indus symbols. The study, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows distinct patterns in the symbols' placement in sequences and creates a statistical model for the unknown language.

"The statistical model provides insights into the underlying grammatical structure of the Indus script," said lead author Rajesh Rao, a UW associate professor of computer science. "Such a model can be valuable for decipherment, because any meaning ascribed to a symbol must make sense in the context of other symbols that precede or follow it."

Co-authors are Nisha Yadav and Mayank Vahia of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and Centre for Excellence in Basic Sciences in Mumbai; Hrishikesh Joglekar of Mumbai; R. Adhikari of the Institute of Mathematical Sciences in Chennai; and Iravatham Mahadevan of the Indus Research Centre in Chennai.

Despite dozens of attempts, nobody has yet deciphered the Indus script. The symbols are found on tiny seals, tablets and amulets, left by people inhabiting the Indus Valley from about 2600 to 1900 B.C. Each artifact is inscribed with a sequence that is typically five to six symbols long.

Some people have questioned whether the symbols represent a language at all, or are merely pictograms of political or religious icons.

The new study looks for mathematical patterns in the sequence of symbols. Calculations show that the order of symbols is meaningful; taking one symbol from a sequence found on an artifact and changing its position produces a new sequence that has a much lower probability of belonging to the hypothetical language. The authors said the presence of such distinct rules for sequencing symbols provides further support for the group's previous findings, reported earlier this year in the journal Science, that the unknown script might represent a language.