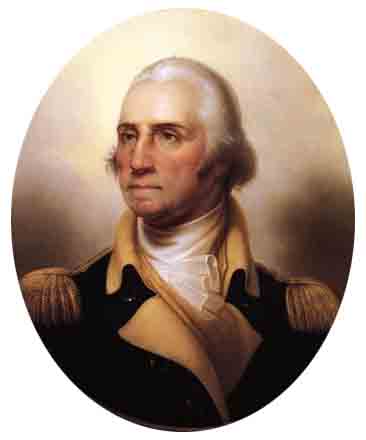

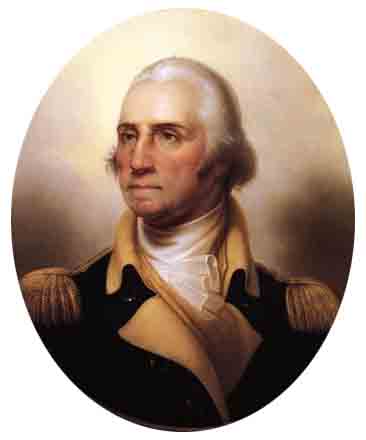

George Washington (February 22, 1732 - December 14, 1799) led America's Continental Army to victory over Britain in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), and was later elected the first president of the United States under the U.S. Constitution. He served two four-year terms from 1789 to 1797, winning reelection in 1792. Because of his central and critical role in the founding of the United States, Washington is referred to as father of the nation. His devotion to republicanism and civic virtue made him an exemplary figure among early American politicians.

In his youth, Washington worked as a surveyor of rural lands and acquired what would become invaluable knowledge of the terrain around his native state of Virginia. Washington gained command experience during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Due to this experience, his military bearing, his enormous charisma, his leadership of the patriot cause in Virginia, and his political base in the largest colony, the Second Continental Congress chose him, in 1775, as their commander-in-chief of the American army.

In 1776, he victoriously forced the British out of Boston. But, later that same year, was badly defeated, and nearly captured, when he lost New York City. However, in the bitter-cold dead of night, he revived the patriot cause, by crossing the Delaware river in New Jersey and defeating the surprised enemy units. As a result of his strategic oversight, Revolutionary forces captured the two main British combat armies, first at Saratoga in 1777 and then at Yorktown in 1781.

He handled relations with the states and their militias, dealt with disputing generals and colonels, and worked with Congress to supply and recruit the Continental army. Negotiating with Congress, the colonial states, and French allies, he held together a tenuous army and fragile birthing nation, amid the constant threats of disintegration and failure. He was also the country's first master spy.

Following the end of the war in 1783, Washington emulated the Roman general Cincinnatus, and retired to his plantation on Mount Vernon, an exemplar of the republican ideal of citizen leadership who rejected power. Alarmed in the late 1780s at the many weaknesses of the new nation under the Articles of Confederation, he presided over the Constitutional Convention that drafted the much stronger United States Constitution in 1787.

In 1789, Washington became President of the United States and promptly established many of the customs and usages of the new government's executive department. He sought to create a great nation capable of surviving in a world torn asunder by war between Britain and France.

His Proclamation of Neutrality of 1793 provided a basis for avoiding any involvement in foreign conflicts. He supported Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton's plans to build a strong central government by funding the national debt, implementing an effective tax system, and creating a national bank. When rebels in Pennsylvania defied Federal authority, he rode at the head of the army to authoritatively quell the Whiskey Rebellion.

Washington avoided the temptation of war and began a decade of peace with Britain via the Jay Treaty in 1795; he used his immense prestige to get it ratified over intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although he never officially joined the Federalist Party, he supported its programs and was its inspirational leader. By refusing to pursue a third term, he made it the enduring norm that no U.S. President should seek more than two. Washington's Farewell Address was a primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against involvement in foreign wars.

As the symbol of republicanism in practice, Washington embodied American values and across the world was seen as the symbol of the new nation. Scholars perennially rank him among the three greatest U.S. Presidents. During Washington's funeral oration, Henry Lee said that of among all Americans, he was "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen."

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 (February 11, 1731, O.S.), the first son of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington, on the family estate (later known as Wakefield) in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Of a wealthy family with firm roots in the Old Country, Washington embarked upon a career as a planter and in 1748 was invited to go with the party that was to survey Baron Fairfax's lands west of the Blue Ridge.

In 1749 he was appointed to his first public office, surveyor of newly created Culpeper County, and through his half-brother Lawrence Washington he became interested in the Ohio Company, which had as its object the exploitation of Western lands.

After Lawrence's death (1752), George inherited part of his estate and took over some of Lawrence's duties as adjutant of the colony. As district adjutant, which made (December 1752) him Major Washington at the age of 20, he was charged with training the militia in the quarter assigned him. In Fredricksburg, also at the age of 20, Washington joined the Freemasons, a fraternal organization that became a lifelong influence.

Washington's Visions and Prophecies

George Washington's Masonic membership, like the others public titles and duties he performed, was expected from a young man of his social status in colonial Virginia. During the War for Independence, General Washington attended Masonic celebration and religious observances in several states. He also supported Masonic Lodges that formed within army regiments.

At his first inauguration in 1791, President Washington took his oath of office on a Bible from St. John's Lodge in New York. During his two terms, he visited Masons in North and South Carolina and presided over the cornerstone ceremony for the U.S. Capitol in 1793. In retirement, Washington became charter Master of the newly chartered Alexandria Lodge No. 22, sat for a portrait in his Masonic regalia, and in death, was buried with Masonic honors.

Such was Washington's character, that from almost the day he took his Masonic obligations until his death, he became the same man in private that he was in public. In Masonic terms, he remained "a just and upright Mason" and became a true Master Mason. Washington was, in Masonic terms, a 'living stone' who became the cornerstone of American civilization. He remains the milestone others civilizations follow into liberty and equality. He is Freemasonry's 'perfect ashlar' upon which countless Master Masons gauge their labors in their own Lodges and in their own communities.

American history is shrouded in secrecy and symbology. Conspiracy theorists try to decode the messages passed down through the ages about humanity's origins and ultimate destiny.

All Seeing Eye - Eye Symbology

At 22 years of age Washington fired some of the first shots of the French and Indian War, soon to become part of the worldwide Seven Years' War. The trouble began in 1753, when France began building a series of forts in the Ohio Country, a region also claimed by Virginia. Governor Dinwiddie sent young Major Washington to the Ohio Country to assess French military strength and intentions, and ask the French to leave. When the French refused, Washington's published report was widely read in both Virginia and Britain.

In 1754, Dinwiddie sent Washington, now commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel in the newly created Virginia Regiment, to drive the French away. Along with his American Indian allies, Washington and his troops ambushed a French scouting party of some 30 men led by Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville, sent from Fort Duquesne to discover if Washington had in fact invaded French-claimed territory. Were this to be the case he was to send word back to the fort, then deliver a formal summons to Washington calling on him to withdraw. His small force was an embassy, resembling Washington's to Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre the preceding year, and he neglected to post sentries around his encampment.

At daybreak on the 28th, Washington with 40 men stole up on the French camp near present Jumonville, Pa. Some were still asleep, others preparing breakfast. Without warning, Washington gave the order to fire. The Canadians who escaped the volley scrambled for their weapons, but were swiftly overwhelmed. Jumonville, the French later claimed, was struck down while trying to proclaim his official summons. Ten of the Canadians were killed, one wounded, all but one of the rest taken prisoner.

Washington and his men then retired, leaving the bodies of their victims for the wolves. Washington then built Fort Necessity, which soon proved inadequate, as he was soon compelled to surrender to a larger French and Indian force. The surrender terms that Washington signed included an admission that he had assassinated Jumonville. Because the French claimed that Jumonville's party had been on a diplomatic (rather than military) mission, the "Jumonville affair" became an international incident and helped to ignite a wider war. Washington was released by the French with his promise not to return to the Ohio Country for one year. Back in Virginia, Governor Dinwiddie broke up the Virginia Regiment into independent companies; Washington resigned from active military service rather than accept a demotion to captain.

In 1755, British General Edward Braddock headed a major effort to retake the Ohio Country. Washington eagerly volunteered to serve as one of Braddock's aides, although the British officers held the colonials in contempt. The expedition ended in disaster at the Battle of the Monongahela. Washington distinguished himself in the debacle - he had two horses shot out from under him, and four bullets pierced his coat - yet, he sustained no injuries and showed coolness under fire. While Washington's exact leadership role during the battle has been debated, biographer Joseph Ellis asserts that Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnant of the British and Virginian forces to a retreat. In Virginia, Washington was acclaimed as a hero.

In fall 1755, Governor Dinwiddie appointed Washington commander in chief of all Virginia forces, with rank of colonel, with responsibility for defending 300 miles (480 km) of mountainous frontier with about 300 men. Washington supervised savage, frontier warfare that averaged two engagements a month. His letters show he was moved by the plight of the frontiersmen he was protecting. With too few troops and inadequate supplies, lacking sufficient authority with which to maintain complete discipline, and hampered by an antagonistic governor, he had a severe challenge. In 1758, he took part in the Forbes Expedition, which successfully drove the French away from Fort Duquesne.

Washington's goal at the outset of his military career had been to secure a commission as a British officer, which had more prestige than serving in the provincial military. However, the British officers had disdain for the amateurish, non-aristocratic Americans. Washington's commission never came; in 1758, Washington resigned from active military service and spent the next sixteen years as a Virginia planter and politician.

On January 6, 1759, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a widow. They had a good marriage, and together raised her two children, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jackie" and "Patsy". Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. George and Martha never had any children together - his earlier bout with smallpox followed, possibly, by tuberculosis may have made him sterile. The newlywed couple moved to Mount Vernon, where he took up the life of a genteel planter and political figure.

Washington's marriage to a wealthy widow greatly increased his property holdings and social standing. He acquired one-third of the 18,000-acre Custis estate upon his marriage, and managed the remainder on behalf of Martha's children. He frequently purchased additional acreage in his own name, and was granted land in what is now West Virginia as a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. By 1775, Washington had doubled the size of Mount Vernon to 6,500 acres with over 100 slaves. As a respected military hero and large landowner, he held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses, beginning in 1758.

Washington first took a leading role in the growing colonial resistance in 1769, when he introduced a proposal drafted by his friend George Mason which called for Virginia to boycott imported English goods until the Townshend Acts were repealed. Parliament repealed the Acts in 1770. Washington regarded the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774 as "an Invasion of our Rights and Privileges". In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the Fairfax Resolves were adopted, which called for, among other things, the convening of a Continental Congress. In August, he attended the First Virginia Convention, where he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.

After fighting broke out in April 1775, Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. Washington had the prestige, the military experience, the charisma and military bearing, the reputation of being a strong patriot, and he was supported by the South, especially Virginia. There was no serious competition. Congress created the Continental Army on June 14; the next day on the nomination of John Adams of Massachusetts it selected Washington as commander-in-chief. Washington assumed command of the American forces in Massachusetts in July 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston. Realising his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. British arsenals were raided (including some in the West Indies) and some manufacturing was attempted; a barely adequate supply (about 2.5 million pounds) was obtained by the end of 1776, mostly from France.

Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, and forced the British to withdraw by putting artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city. The British evacuated Boston and Washington moved his army to New York City.

Washington was widely admired in Britain, where the press was virtually unanimous in portraying him in a positive light. Although negative toward the patriots in the Continental Congress, British newspapers routinely praised Washington's personal character and qualities as a military commander. Moreover, both sides of the aisle in Parliament found the American general's courage, endurance, and attentiveness to the welfare of his troops worthy of approbation and examples of the virtues they and most other Britons found wanting in their own commanders. Washington's refusal to become involved in politics buttressed his reputation as a man fully committed to the military mission at hand and above the factional fray.

In August 1776, British General William Howe launched a massive naval and land campaign to capture New York designed to seize New York City and offer a negotiated settlement. Several defeats against Howe sent Washington scrambling out of New York and across New Jersey, leaving the future of the Continental Army in doubt. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a counterattack, leading the American forces across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey.

Washington was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. On September 26, Howe outmaneuvered Washington and marched into Philadelphia unopposed. Washington's army unsuccessfully attacked the British garrison at Germantown in early October. Meanwhile Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army at Saratoga. The victory caused France to enter the war as an open ally, turning the Revolution into a major world-wide war. Washington's loss of Philadelphia prompted some members of Congress to discuss removing Washington from command. This episode failed after Washington's supporters rallied behind him.

Washington's army encamped at Valley Forge in December 1777, where it stayed for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of 10,000) died from disease and exposure. The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian general staff. The British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778 and returned to New York City. Meanwhile, Washington remained with his army outside New York. He delivered the final blow in 1781, after a French naval victory allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The surrender at Yorktown on October 17, 1781 marked the end of fighting. The Treaty of Paris (1783) recognized the independence of the United States.

In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a group of Army officers who had threatened to confront Congress regarding their back pay. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers.

A few days later, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession of the city; at Fraunces Tavern in the city on December 4, he formally bade his officers farewell. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress of the Confederation.

Washington's retirement to Mount Vernon was short-lived. He was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, and he was unanimously elected president of the Convention. For the most part, he did not participate in the debates involved (though he did participate in voting for or against the various articles), but his prestige was great enough to maintain collegiality and to keep the delegates at their labors. The delegates designed the presidency with Washington in mind, and allowed him to define the office once elected. After the Convention, his support convinced many, including the Virginia legislature, to vote for ratification; all 13 states did ratify the new Constitution.

The walls of Mount Vernon, American Founding Father George Washington's former residence, were likely witness to all sorts of historical secrets we'll never know about IFL Science - June 21, 2024

It turns out there’s plenty to be found under the floorboards - nearly 30 glass bottles of perfectly preserved cherries and berries

Washington was elected unanimously by the Electoral College in 1789, and he remains the only person ever to be elected president unanimously (a feat which he duplicated in the 1792 election). As runner-up with 34 votes (each elector cast two votes), John Adams became vice president. Washington took the oath of office as the first President on April 30, 1789 at Federal Hall in New York City.

The First U.S. Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year - a large sum in 1789. Washington, already wealthy, declined the salary, since he valued his image as a selfless public servant. At the urging of Congress, however, he ultimately accepted the payment. A dangerous precedent could have been set otherwise, as the founding fathers wanted future presidents to come from a large pool of potential candidates - not just those citizens that could afford to do the work for free.

Washington attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President" to the more majestic names suggested.

Washington proved an able administrator. An excellent delegator and judge of talent and character, he held regular cabinet meetings, which debated issues; he then made the final decision and moved on. In handling routine tasks, he was "systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of particular actions with them."

Washington only reluctantly agreed to serve a second term of office as president. He refused to run for a third, establishing the precedent of a maximum of two terms for a president.

Washington was not a member of any political party, and hoped that they would not be formed. His closest advisors, however, became divided into two factions, setting the framework for political parties. Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, who had bold plans to establish the national credit and build a financially powerful nation, formed the basis of the Federalist Party. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, founder of the Jeffersonian Republicans, strenuously opposed Hamilton's agenda, but Hamilton had Washington's ear, not Jefferson.

In 1791, Congress imposed an excise tax on distilled spirits, which led to protests in frontier districts, especially Pennsylvania. By 1794, after Washington ordered the protesters to appear in U.S. district court, the protests turned into full-scale riots known as the Whiskey Rebellion. The federal army was too small to be used, so Washington invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia and several other states. The governors sent the troops and Washington took command, marching into the rebellious districts. There was no fighting, but Washington's forceful action proved the new government could protect itself. It also was one of only two times that a sitting President would personally command the military in the field: the other was after President James Madison fled the burning White House in the War of 1812. These events marked the first time under the new constitution that the federal government used strong military force to exert authority over the states and citizens.

In 1793, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genet, called "Citizen Genet," to America. Genet issued letters of marque and reprisal to American ships so they could capture British merchant ships. He attempted to turn popular sentiment towards American involvement in the French war against Britain by creating a network of Democratic-Republican Societies in major cities. Washington rejected this interference in domestic affairs, demanded the French government recall Genet, and denounced his societies.

To normalize trade relations with Britain, remove them from western forts, and resolve financial debts left over from the Revolution, Hamilton and Washington designed the Jay Treaty. It was negotiated by John Jay, and signed on November 19, 1794. The Jeffersonians supported France and strongly attacked the treaty. Washington and Hamilton, however, mobilized public opinion and won ratification by the Senate by emphasizing Washington's support. The British agreed to depart their forts around the Great Lakes, the Canadian-U.S. boundary was adjusted, numerous pre-Revolutionary debts were liquidated, and the British opened their West Indies colonies to the American trade. Most important, the treaty avoided war with Britain and instead brought a decade of prosperous trade with Britain. It angered the French and became a central issue in the political debates of the emerging First Party System.

Washington's Farewell Address (issued as a public letter in 1796) was one of the most influential statements of American political values.

Drafted primarily by Washington himself, with help from Hamilton, it gives advice on the necessity and importance of national union, the value of the Constitution and the rule of law, the evils of political parties, and the proper virtues of a republican people. In the address, he called morality "a necessary spring of popular government." He suggests that "reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle." Washington thus makes the point that the value of religion is for the benefit of society as a whole.

Washington warns against foreign influence in domestic affairs and American meddling in European affairs. He warns against bitter partisanship in domestic politics and called for men to move beyond partisanship and serve the common good. He called for an America wholly free of foreign attachments, as the United States must concentrate only on American interests. He counseled friendship and commerce with all nations, but warned against involvement in European wars and entering into long-term alliances. The address quickly set American values regarding religion and foreign affairs, and his advice was often repeated in political discourse well into the twentieth century; not until the 1949 formation of NATO would the United States again sign a treaty of alliance with a foreign nation. Washington strictures against political parties were ignored at the time and ever since.

After retiring from the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. He devoted much time to farming and, in that year, constructed a 2,250 square foot distillery, which was one of the largest in the new republic. Two years later, he produced 11,000 gallons of whiskey worth $7,500.

In 1798, Washington was appointed Lieutenant General in the United States Army (then the highest possible rank) by President John Adams. Washington's appointment was to serve as a warning to France, with which war seemed imminent.

On December 12, 1799, Washington spent several hours inspecting his farms on horseback, in snow and later hail and freezing rain. He sat down to dine that evening without changing his wet clothes. The next morning, he awoke with a bad cold, fever and a throat infection called quinsy that turned into acute laryngitis and pneumonia.

Washington died on the evening of December 14, 1799, at his home, while attended by Dr. James Craik, one of his closest friends, and Tobias Lear, Washington's personal secretary. Lear would record the account in his journal. From Lear's account, we receive Washington's last words: Tis well.

Modern doctors believe that Washington died from either epiglottitis or, since he was bled as part of the treatment, a combination of shock from the loss of five pints of blood, as well as asphyxia and dehydration. Washington's remains were buried at Mount Vernon. In order to protect their privacy, Martha Washington burned the correspondence between her husband and herself following his death. Only three letters between the couple have survived.

After Washington's death, Mount Vernon was inherited by his nephew, Bushrod Washington, a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1861, Washington's remains were moved from Mount Vernon to Lexington, Virginia, as there was fear that Northern troops would desecrate them. They were returned at the end of the war.

During the United States Bicentennial year George Washington was appointed posthumously to the grade of General of the Armies of the United States by the congressional joint resolution s:Public Law 94-479 on January 19, 1976, approved by President Gerald R. Ford on October 11, 1976, with an effective appointment date of July 4, 1976.

As early as 1778, Washington was lauded as the "Father of His Country"

Cultural depictions of George Washington

Washington is commemorated on the U.S. quarter.

Today, Washington's face and image are often used as national symbols of the United States, along with the icons such as the flag and great seal. Perhaps the most pervasive commemoration of his legacy is the use of his image on the one-dollar bill and the quarter-dollar coin. Washington, together with Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln, is depicted in stone at the Mount Rushmore Memorial.

Many things have been named in honor of Washington. Washington's name became that of the nation's capital, Washington, DC, and the State of Washington, the only state to be so named (Maryland, the Virginias, the Carolinas and Georgia are named in honor of British monarchy). The George Washington University and the Washington Monument, one of the most well-known American landmarks, were built in his honor. The George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia was also built in his honor. It was however, constructed entirely with voluntary contributions from members of the Masonic Fraternity.

For most of his life, Washington operated his plantations as a typical Virginia slave owner. In the 1760s, he dropped tobacco (which was prestigious but unprofitable) and shifted to wheat growing and diversified into milling flour, weaving cloth, and distilling brandy. By the time of his death, there were 317 slaves at Mount Vernon.

Before the American Revolution, Washington expressed no moral reservations about slavery, but, by 1778, he had stopped selling slaves without their consent because he did not want to break up slave families.

In 1778, while Washington was at war, he wrote to his manager at Mount Vernon that he wished to sell his slaves and "to get quit of negroes", since maintaining a large (and increasingly elderly) slave population was no longer economically efficient. Washington could not legally sell the "dower slaves", however, and because these slaves had long intermarried with his own slaves, he could not sell his slaves without breaking up families.

After the war, Washington often privately expressed a dislike of the institution of slavery. Despite these privately expressed misgivings, Washington never criticized slavery in public. In fact, as President, Washington brought nine household slaves to the Executive Mansion in Philadelphia. By Pennsylvania law, slaves who resided in the state became legally free after six months. Washington rotated his household slaves between Mount Vernon and Philadelphia so that they did not earn their freedom, a scheme he attempted to keep hidden from his slaves and the public and one which was, in fact, against the law.

Washington was the only prominent, slaveholding Founding Father to emancipate his slaves. He did not free his slaves in his lifetime, however, but instead included a provision in his will to free his slaves upon the death of his wife. It is important to understand that not all the slaves at his estate at Mt. Vernon were owned by him. His wife Martha owned a large number of slaves and Washington, himself did feel that he could free slaves that come to Mt. Vernon from her estate. His actions were influenced by his close relationship with the Marquis de La Fayette. Martha Washington would free slaves to which she had title late in her own life. He did not speak out publicly against slavery, argues historian Dorothy Twohig, because he did not wish to risk splitting apart the young republic over what was already a sensitive and divisive issue.

Washington was baptized as an infant into the Church of England.

In 1765, when the Church of England was still the state religion, he served on the vestry (lay council) for his local church. Throughout his life, he spoke of the value of righteousness, and of seeking and offering thanks for the "blessings of Heaven". He endorsed religion rhetorically and in his 1796 Farewell Address remarked on its importance in building moral character in American citizenry, believing morality undergirded all public order and successful popular government. In a letter to George Mason in 1785, he wrote that he was not among those alarmed by a bill "making people pay towards the support of that [religion] which they profess", but felt that it was "impolitic" to pass such a measure, and wished it had never been proposed, believing that it would disturb public tranquility.

His adopted daughter, Nelly Custis Lewis, stated: "I have heard her Nelly's mother, Eleanor Calvert Custis, say that General Washington always received the sacrament with my grandmother Martha Washington before the revolution". After the revolution, Washington frequently accompanied his wife to Christian church services; however, there is no record of his ever taking communion, and he would regularly leave services before communion - with the other non-communicants (as was the custom of the day), until he ceased attending at all on communion Sundays. Historians and biographers continue to debate the degree to which he can be counted as a Christian, and the degree to which he was a deist. It should also be noted that Washington was a Freemason. Even a few portraits exist of Washington in Masonic regalia.

Washington was an early supporter of religious toleration. In 1775, he ordered that his troops not show anti-Catholic sentiments by burning the pope in effigy on Guy Fawkes Night. When hiring workmen for Mount Vernon, he wrote to his agent, "If they be good workmen, they may be from Asia, Africa, or Europe; they may be Mohammedans (Muslims), Jews, or Christians of any sect, or they may be Atheists.

Although the sport of cricket is not a common interest in modern America, it has been popular in the past. It is well understood from anecdotal evidence that George Washington was a strong supporter of cricket, participating at least one occasion in games of cricket with his troops at Valley Forge during the Revolution. This is a sporting passion that other presidents have shared, such as Abraham Lincoln.

Though Washington had no children, he did have two successful nephews. Bushrod Washington became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court and Burwell Bassett was a longtime congressman in both Virginia State and United States government.

An early biographer, Parson Weems, was the source of the famous story about young Washington cutting down a cherry tree and confessing this to his father, in an 1800's book entitled The Life of George Washington; With Curious Anecdotes, Equally Honorable to Himself and Exemplary to His Young Countrymen. Some historians believe Weems invented or greatly embellished the dialogue, while others build Weems credibility by citing the facts that he did interview older people who knew young Washington. Weems did not, in fact, include the cherry tree story until the fifth edition of this work; he ascribed it to an "excellent lady," not otherwise identified. Even so, a careful reading of the account does not state that young George "cut down" the cherry tree, only that he hacked it so badly that he killed it. (and, also within the context of the story, he had just been given the hatchet as a gift and would be, in his father's eyes, the only likely suspect.)

A popular belief is that Washington wore a wig, as was the fashion among some at the time. He did not wear a wig; he did, however, powder his hair, as represented in several portraits, including the well-known unfinished Gilbert Stuart depiction.

An old legend about Washington was that he threw or skipped a silver dollar across the Potomac River. One would need a strong arm to throw an object across the Potomac, for it is about a mile wide at Mount Vernon. More likely he threw an object across the Rappahannock River, the river on which his childhood home stood.

Washington's teeth were not made out of wood, as was once commonly believed. They were made out of teeth from different kinds of animals, specifically elk, hippopotamus, and human. One set of his false teeth weighed almost four ounces (110 g) and were made out of lead.

A famous 1866 engraving depicts Washington praying at Valley Forge. In 1918, the Valley Forge Park Commission declined to erect a monument to the prayer because they could find no evidence that the event had occurred. In contrast, the Valley Forge Historical Society published an article in 1945 reviewing this issue and concludes that there is abundant evidence demonstrating that Washington was a prayerful and privately religious man although the second hand accounts of the tradition "lack ... the authentication with which the historian seeks to monument his recordings in all the solemnity of established fact."

George Washington's vision is recorded at the Library of Congress

Valley Forge, the winter of 1777, American forces were fighting against the British, the most powerful nation in the world. Many believe that only 3% of the American people took part in the struggle for independence, while "Tories" gave aid and comfort to the British cause.

"This afternoon, as I was sitting at this table engaged in preparing a dispatch, something seemed to disturb me. Looking up, I beheld standing opposite me a singularly beautiful female. So astonished was I, for I had given strict orders not to be disturbed, that it was some moments before I found language to inquire the cause of her presence. A second, a third and even a fourth time did I repeat my question, but received no answer from my mysterious visitor except a slight raising of her eyes.

"By this time I felt strange sensations spreading through me. I would have risen but the riveted gaze of the being before me rendered volition impossible. I assayed once more to address her, but my tongue had become useless, as though it had become paralyzed.

"A new influence, mysterious, potent, irresistible, took possession of me. All I could do was to gaze steadily, vacantly at my unknown visitor, Gradually the surrounding atmosphere seemed as if it had become filled with sensations, and luminous. Everything about me seemed to rarify, the mysterious visitor herself becoming more airy and yet more distinct to my sight than before. I now began to feel as one dying, or rather to experience the sensations which I have sometimes imagined accompany dissolution. I did not think, I did not reason, I did not move; all were alike impossible. I was only conscious of gazing fixedly, vacantly at my companion.

"Presently I heard a voice saying, `Son of the Republic, look and learn,' while at the same time my visitor extended her arm eastwardly. I now beheld a heavy white vapor at some distance rising fold upon fold. This gradually dissipated, and I looked upon a strange scene. Before me lay spread out in one vast plain all the countries of the world; Europe, Asia, Africa and America. I saw rolling and tossing between Europe and America the billows of the Atlantic, and between Asia and America lay the Pacific.

"Son of the Republic' said the same mysterious voice as before, `look and learn,' At that moment I beheld a dark, shadowy being, like an angel, standing, or rather floating in mid-air, between Europe and America. Dipping water out of the ocean in the hollow of each hand, he sprinkled some upon America with his right hand, while with his left hand he cast some on Europe. Immediately a cloud raised from these countries, and joined in mid-ocean. For a while it remained stationary, and then moved slowly westward, until it enveloped America in its murky folds. Sharp flashes of lightning gleamed through it at intervals, and I heard the smothered groans and cries of the American people.

"A second time the angel dipped water from the ocean, and sprinkled it out as before. The dark cloud was then drawn back to the ocean, in whose heaving billows it sank from view. A third time I heard the mysterious voice saying, `Son of the Republic, look and learn,' I cast my eyes upon America and beheld villages and towns and cities springing up one after another until the whole land from the Atlantic to the Pacific was dotted with them.

"Again, I heard the mysterious voice say, `Son of the Republic, the end of the century cometh, look and learn.' At this the dark shadowy angel turned his face southward, and from Africa I saw an ill-omened spectre approach our land. It flitted slowly over every town and city of the latter. The inhabitants presently set themselves in battle array against each other. As I continued looking I a saw bright angel, on whose brow rested a crown of light, on which was traced the word `Union,' bearing the American flag which he placed between the divided nation, and said, `Remember ye are brethren.' Instantly, the inhabitants, casting from them their weapons became friends once more, and united around the National Standard.

"And again I heard the mysterious voice saying, `Son of the Republic, look and learn.' At this the dark, shadowy angel placed a trumpet to his mouth, and blew three distinct blasts; and taking water from the ocean, he sprinkled it upon Europe, Asia and Africa. Then my eyes beheld a fearful scene: from each of these countries arose thick, black clouds that were soon joined into one. Throughout this mass there gleamed a dark red light by which I saw hordes of armed men, who, moving with the cloud, marched by land and sailed by sea to America. Our country was enveloped in this volume of cloud, and I saw these vast armies devastate the whole country and burn the villages, towns and cities that I beheld springing up. As my ears listened to the thundering of the cannon, clashing of swords, and the shouts and cries of millions in mortal combat, I heard again the mysterious voice saying, `Son of the Republic, look and learn.' When the voice had ceased, the dark shadowy angel placed his trumpet once more to his mouth, and blew a long and fearful blast.

"Instantly a light as of a thousand suns shone down from above me, and pierced and broke into fragments the dark cloud which enveloped America. At the same moment the angel upon whose head still shone the word Union, and who bore our national flag in one hand and a sword in the other, descended from the heavens attended by legions of white spirits. These immediately joined the inhabitants of America, who I perceived were well nigh overcome, but who immediately taking courage again, closed up their broken ranks and renewed the battle.

"Again, amid the fearful noise of the conflict, I heard the mysterious voice saying, `Son of the Republic, look and learn.' As the voice ceased, the shadowy angel for the last time dipped water from the ocean and sprinkled it upon America. Instantly the dark cloud rolled back, together with the armies it had brought, leaving the inhabitants of the land victorious!

"Then once more I beheld the villages, towns and cities springing up where I had seen them before, while the bright angel, planting the azure standard he had brought in the midst of them, cried with o loud voice" `While the stars remain, and the heavens send down dew upon the earth, so long shall the Union last.' And taking from his brow the crown on which blazoned the word `UNION,' he placed it upon the Standard while the people, kneeling down, said, `Amen.'

"The scene instantly began to fade and dissolve, and I at last saw nothing but the rising, curling vapor I at first beheld. This also disappearing, I found myself once more gazing upon the mysterious visitor, who, in the same voice I had heard before, said, `Son of the Republic, what you have seen is thus interpreted: three great perils will come upon the Republic. The most fearful is the third, but in this greatest conflict the whole world united shall not prevail against her. Let every child of the Republic learn to live for his God, his land and the Union. With these words the vision vanished, and I started from my seat and felt that I had seen a vision wherein had been shown to me the birth, progress and destiny of the United States."

In his farewell address, Washington spoke of several avenues of tyranny, including selfish ambition (with pretended patriotism,) collusion of powers, usurpation and precedence of usurpation, debt, foreign influence, and rank party politics.

As for collusion of powers, he warned, "The habits of thinking in a free country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration to confine themselves within their respective constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one and thus to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism."

On usurpation, he warned, "If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit which the use can at any time yield."

George Washington's last words were "Tis well."