Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera whose forelimbs form webbed wings, making them the only mammals naturally capable of true and sustained flight. By contrast, other mammals said to fly, such as flying squirrels, gliding possums, and colugos, can only glide for short distances. Bats do not flap their entire forelimbs, as birds do, but instead flap their spread-out digits,[4] which are very long and covered with a thin membrane or patagium. Read more ...

Largest Bat In Europe Inhabited Northeastern Spain More Than 10,000 Years Ago Science Daily - October 30, 2009

Spanish researchers have confirmed that the largest bat in Europe, Nyctalus lasiopterus, was present in north-eastern Spain during the Late Pleistocene. The Greater Noctule fossils found in the excavation site at Abric Romani prove that this bat had a greater geographical presence more than 10,000 years ago than it does today, having declined due to the reduction in vegetation cover.

Bat fossil solves evolution poser BBC - February 13, 2008

A fossil found in Wyoming has resolved a long-standing question about when bats gained their sonar-like ability to navigate and locate food. They found that flight came first, and only then did bats develop echolocation to track and trap their prey. A large number of experts had previously thought this happened the other way around.

Echolocation - the ability to emit high-pitched squeaks and hear, for example, the echo bouncing off flying insects as small as a mosquito - is one of the defining features of bats as a group. There are over 1,000 species of bats in the world today, and all of them can echolocate to navigate and find food. But some, especially larger fruit bats, depend on their sense of smell and sight to find food, showing that the winged mammals could survive without their capacity to gauge the location, direction and speed of flying creatures in the dark.

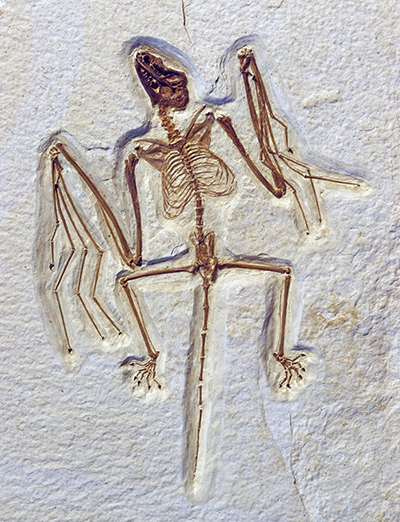

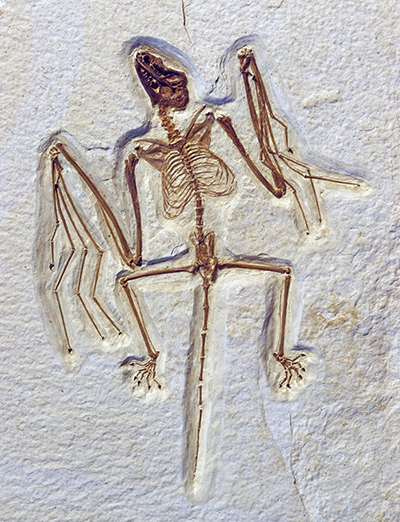

The new fossil, named Onychonycteris finneyi, was found in the 52-million-year-old Green River Formation in Wyoming, US, in 2003. It is in a category all on its own, giving rise to a new genus and family. Its large claws, primitive wings, broad tail and especially its underdeveloped cochlea - the part of the inner ear that makes echolocation possible - all set it apart from existing species. It is also drastically different from another bat fossil unearthed in 1960, Icaronycteris index, that lived during the same Early Eocene epoch.

Many experts had favored an "echolocation first" theory because this earlier find, also from the Green River geological formation in Wyoming, was so close in its anatomy to modern species. But the new fossil suggests this wasn't the case. "Its teeth seem to show that it was an insect eater," said co-author Kevin Seymour, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. "And if it wasn't echolocating then it had to be using other methods to find food." The next big question to be answered, he added, was when and how bats made the transition from being terrestrial to flying animals .

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS