The Etruscan civilization flourished in central Italy between the 8th and 3rd century BCE. The culture was renowned in antiquity for its rich mineral resources and as a major Mediterranean trading power. Much of its culture and even history was either obliterated or assimilated into that of its conqueror, Rome. Nevertheless, surviving Etruscan tombs, their contents and their wall paintings, as well as the Roman adoption of certain Etruscan clothing, religious practices, and architecture, are convincing testament to the great prosperity and significant contribution to Mediterranean culture achieved by Italy's first great civilization.

The Villanovan culture developed during the Iron Age in central Italy from around 1100 BCE. The name is actually misleading as the culture is, in fact, the Etruscans in their early form. There is no evidence of migration or warfare to suggest the two peoples were different. The Villanovan culture benefitted from a greater exploitation of the area's natural resources, which allowed villages to form. Houses were typically circular and made of wattle and daub walls and thatch roofs with wooden and terracotta decoration added; pottery models survive which were used to store the ashes of the deceased. With the guarantee of regular, well-managed crops a portion of the community was able to devote itself to manufacturing and trade. The importance of horses is seen in the many finds of bronze horse bits in the large Villanovan cemeteries located just outside their settlements. By around 750 BCE the Villanovan culture had become the Etruscan culture proper, and many of the Villanovan sites would continue to develop as major Etruscan cities. The Etruscans were now ready to establish themselves as one of the most successful population groups in the ancient Mediterranean.

The Etruscan cities were independent city-states linked to each other only by a common religion, language, and culture in general. Geographically spread from the Tiber River in the south to parts of the Po Valley in the north, the major Etruscan cities included Cerveteri (Cisra), Chiusi (Clevsin), Populonia (Puplona), Tarquinia (Tarchuna), Veii (Vei), Vetulonia (Vetluna), and Vulci (Velch). Cities developed independently so that innovations in such areas as manufacturing, art and architecture, and government occurred at different times in different places. Generally speaking, coastal sites, with their greater contact with contemporary cultures, evolved quicker but eventually passed on new ideas to the Etrurian hinterland. Nevertheless, the Etruscan cities still developed along their own lines, and significant differences are evident in one city from another.

Prosperity was based on fertile lands and improved agricultural tools to better exploit it; rich local mineral resources, especially iron; the manufacture of metal tools, pottery, and goods in precious materials such as gold and silver; and a trade network which connected the Etruscan cities to each other, to tribes in the north of Italy and across the Alps, and to other maritime trading nations such as the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, and the Near East in general. Whilst slaves, raw materials, and manufactured goods (especially Greek pottery) were imported, the Etruscans exported iron, their own indigenous bucchero pottery, and foodstuffs, notably wine, olive oil, grain, and pine nuts.

With trade flourishing from the 7th century BCE, the cultural impact of the consequent increase in contact between cultures also became more profound. Craftsmen from Greece and the Levant settled in emporia Ð semi-independent trading ports that sprang up on the Tyrrhenian coast, most famously at Pyrgri, one of the ports of Cerveteri. Eating habits, clothing, the alphabet, and religion are just some of the areas where Greek and Near Eastern peoples would transform Etruscan culture in the so-called 'Orientalising' period.

Etruscan cities teamed with Carthage to successfully defend their trade interests against a Greek naval fleet at the Battle of Alalia (aka Battle of the Sardinian Sea) in 540 BCE. Such was the Etruscan dominance of the seas and maritime trade along the Italian coast that the Greeks repeatedly referred to them as scoundrel pirates. In the 5th century BCE, though, Syracuse was the dominant Mediterranean trading power, and the Sicilian city combined with Cumae to inflict a naval defeat on the Etruscans at the battle at Cumae in 474 BCE. Worse was to come when the Syracusan tyrant Dionysius I decided to attack the Etruscan coast in 384 BCE and destroy many of the Etruscan ports. These factors contributed significantly to the loss of trade and consequent decline of many Etruscan cities seen from the 4th to 3rd century BCE.

Inland, Etruscan warfare seems to have initially followed Greek principles and the use of hoplites Ð wearing a bronze breastplate, Corinthian helmet, greaves for the legs, and a large circular shield Ð deployed in the static phalanx formation, but from the 6th century BCE, the greater number of smaller round bronze helmets would suggest a more mobile warfare. Although several chariots have been discovered in Etruscan tombs, it is likely that these were for ceremonial use only. The minting of coinage from the 5th century BCE suggests that mercenaries were used in warfare, as they were in many contemporary cultures. In the same century, many towns built extensive fortification walls with towers and gates. All of these developments point to a new military threat, and it would come from the south where a great empire was about to be built, starting with the conquest of the Etruscans. Rome was on the warpath.

In the 6th century BCE some of Rome's early kings, although legendary, were from Tarquinia, but by the late 4th century BCE Rome was no longer the lesser neighbour of the Etruscans and was beginning to flex its muscles. In addition, the Etruscan cause was not in any way helped by invasions from the north by Celtic tribes from the 5th to 3rd century BCE, even if they would sometimes be their allies against Rome. There would follow some 200 years of intermittent warfare. Peace treaties, alliances, and temporary truces were punctuated by battles and sieges such as Rome's 10-year attack on Veii from 406 BCE and the siege of Chiusi and Battle of Sentinum, both in 295 BCE. Eventually, Rome's professional army, its greater organizational skills, superior manpower and resources, and the crucial lack of political unity amongst the Etruscan cities meant that there could only be one winner. 280 BCE was a significant year and saw the fall of Tarquinia, Orvieto, and Vulci, amongst others. Cerveteri fell in 273 BCE, one of the last to hold out against the relentless spread of what was fast becoming a Roman empire.

The Romans often butchered and sold into slavery the vanquished, established colonies, and repopulated areas with veterans. The end finally came when many Etruscan cities supported Marius in the civil war won by Sulla who promptly sacked them all over again in 83 and 82 BCE. The Etruscans became Romanized, their culture and language giving way to Latin and Latin ways, their literature destroyed, and their history obliterated. It would take 2,500 years and the almost miraculous discovery of intact tombs stuffed with exquisite artefacts and decorated with vibrant wall paintings before the world realised what had been lost.

Etruscan culture developed in northern and central Italy after ca 800 BC without a serious break out of the preceding Villanovan culture. The Villanovan culture, the earliest Iron Age culture of central and northern Italy, gave way in the 7th century to an increasingly orientalising culture that was influenced by Greek traders and Greek neighbors in Magna Graecia, the Hellenic civilization of southern Italy. The Etruscan civilization flourished in Etruria and the Po valley in the northern part of what is now Italy, prior to the arrival of Gauls in the Po valley and the formation of the Roman Republic.

Etruscan history is rooted in layers of mystery. Throughout time art historians and archaeologists have tried to milk truths of Etruscan culture from sources plagued by holes and ambiguities.

Much of what we have come to know of Etruscan culture has stemmed from the writings of other cultures, mainly that of the Greeks and the Romans, and directly from archaeological evidence gathered from the objects they left behind.

The land of Etruria occupied what is now Tuscany in central Italy. The origin of the Etruscans is still an object of debate and a mystery that has sparked investigation by many great writers and scholars.

In the first century B.C., a Greek named Dionysius of Halicarnassus studied the early cultures of Italy in Rome; he came to believe that the Etruscans originated from the Pelasgians who settled with natives of the area, only to be taken over by the Tyrrhenians.

In the beginning of the first century AD, Livy and Virgil believed that the migration of the Etruscans to central Italy was resultant of the fall of Troy and flight of Aeneas.

Then in fifth century Greece, Herodotus insisted that the Etruscans traveled from Lydia to Italy due to famine; their leader at that time was Tyrrhenos, from whom they adopted the name the Tyrrhenians.

Now, modern thinkers follow the postulations of Herodotus or Dionysius. And, new research shows that the Etruscans were descendants of people who thrived in the ninth to eighth centuries BC known as the Villanovans. Etruscan cities began to arise in the seventh century BC where Villanovan villages had been.

The first Etruscan pieces to be discovered were two bronzes found in 1553 and 1556 during the Renaissance. Etruscan excavations began in the eighteenth century, and in the nineteenth century major archaeological evidence was found at Tarquinia, Cerveteri, and Vulci.

At that point, Estrucan culture and the mysteries surrounding it gained notice by museums which started to collect the objects unearthed in the digs.

In the twentieth century archaeologists began to use sonar photographic sound, a means that determines whether or not excavation would be lucrative before entering a burial chamber; this and other technology has allowed for more than 6,000 grave sites to be examined.

Among all that has been discovered through these various times and means of investigation and excavation, there are no Etruscan literary works or historical accounts. There are, however, many writing samples carved on tombs. The Etruscan writing system is unique in that its letters come from the Greek alphabet, yet its grammatical structure is unlike any other European language. The epitaphs usually tell of the person's name, class, occupation, and also sometimes delineate whom he or she was related to, thus enabling experts to elicit certain genealogies.

Other conclusive information about the Etruscans comes from writers of other times. Religion was at the heart of Etruscan culture. The Romans themselves depended on some Etruscan books of divination, that is, the practice of foretelling the future, and determining the will of the gods through signs. The Etruscans followed three books of divination concerned with reading entrails of animals, lightning, and the flight patterns of birds respectively.

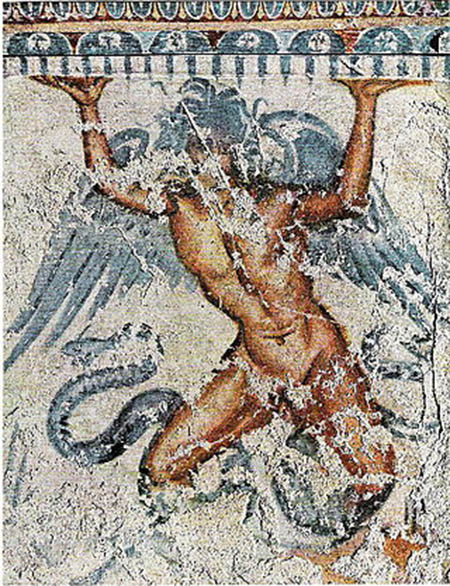

The Etruscans myths were heavily influenced by the Greeks, mainly the fact that their gods possessed human attributes and dispositions. The Etruscans often combined Greek influences with stories of their own. There is also mythology purely Etruscan, in accordance with which many cults gathered in dedication to their gods. In Etruscan religion, the realms occupied by humans and by the gods are very specific, and their practices followed very exact procedures to avoid ill will of the gods.

On a political and economical level, the Etruscans are known as great seafarers, and wealthy miners of iron, copper, tin, lead, and silver. These two sources of wealth lead them to the zenith of their cultural and political power in the sixth century. Also around this time, Latin cities were erected and influenced greatly by the flourishing Etruscan culture surrounding them.

However, Latin cultures soon united with some of the Greek settlements, and in 504 BC, the Etruscans were driven from Latium when their army was defeated.

After this, Tarquinius Superbus the Etruscan king of Rome fell, and the Roman republic formed; from this point on, Roman history is rooted in Latin culture instead of that of the Etruscans.

The decline in Etruscan wealth manifested itself in their tombs, ever growing in modesty, the end of public building and importing of Attic pottery, and a dramatic decrease in political participation.

In 386 B.C., the Gauls took over Rome and the Po valley, causing the Etruscans to lose their trading routes across the Alps. Toward the end of fourth century B.C., the Etruscans rebelled against the Roman republic , but were defeated despite help from allies of Gauls, Samnites, and Lucancians.

In 282 B.C. they accepted a peace treaty after suffering another defeat. Within a few years, all Etruscan cities were taken over by Rome, and the Etruscans thus vanished from the political realms of the world.

The early government of the Etruscan cities was based on a monarchy but later developed into rule by an oligarchy who supervised and dominated all public positions and a popular assembly of citizens where these existed. The only evidence of a political connection between cities is an annual meeting of the Etruscan League. This is a body we know next to nothing about except that the 12 or 15 of the most important cities sent elders to meet together, largely for religious purposes, at a sanctuary called Fanum Voltumnae whose location is unknown but was probably near Orvieto. There is also ample evidence that Etruscan cities occasionally fought each other and even displaced the populations of lesser sites, no doubt, a consequence of the competition for resources which was driven both by population increases and by a desire to control increasingly lucrative trade routes.

Etruscan society had various levels of social status from foreigners and slaves to women and male citizens. Males of certain clan groups seem to have dominated key roles in the areas of politics, religion and justice and one's membership of a clan was likely more important than even which city one came from. Women enjoyed more freedom than in most other ancient cultures, for example, being able to inherit property in their own right, even if they were still not equal to males and unable to participate in public life beyond social and religious occasions.

The fall of the Etruscan state can be attributed to a variety of factors, the most influential being its disunity. The Etruscan state government was essentially a theocracy. The Etruscans met annually at the shrine of Voltumna to discuss military and political affairs. Apart from this, the Etruscans could be considered, as many ancient sources describe them, "duodecim populi Eturiae" or "the twelve peoples of Eturia". Although the divisions between the states were not as extreme as those found in ancient Greece, individual states were under no obligation to provide aid to one another, and frequently found it difficult to unify against one threat.

For this reason, the Romans attacked and annexed individual cities between 510 and 29 BC. This disunity is further illustrated by the fact that Rome created treaties individually with the Etruscan states, rather than the whole. With the fall of Veii to the Romans, a key southern defense was destroyed, leaving the Etruscans pressed in on from all sides by several different forces, and ripe for conquest.

The princely tombs were not of individuals. The inscription evidence shows that families were interred there over long periods, marking the growth of the aristocratic family as a fixed institution, parallel to the gens at Rome and perhaps even its model. The Etruscans could have used any model of the eastern Mediterranean. That the growth of this class is related to the new acquisition of wealth through trade is unquestioned. The wealthiest cities were located near the coast. At the centre of the society was the married couple, tusurthir. The Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized pairing.

Similarly, the behavior of some wealthy women is not uniquely Etruscan. The apparent promiscuous revelry has a spiritual explanation. Swaddling and Bonfante (among others) explain that depictions of the nude embrace, or symplegma, "had the power to ward off evil", as did baring the breast, which was adopted by western culture as an apotropaic device, appearing finally on the figureheads of sailing ships as a nude female upper torso. It is also possible that Greek and Roman attitudes to the Etruscans were based on a misunderstanding of the place of women within their society. In both Greece and Republican Rome, respectable women were confined to the house and mixed-sex socialising did not occur. Thus, the freedom of women within Etruscan society could have been misunderstood as implying their sexual availability.[original research?] It is worth noting that a number of Etruscan tombs carry funerary inscriptions in the form "X son of (father) and (mother)", indicating the importance of the mother's side of the family.

The Etruscans, like the contemporary cultures of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome had a persistent military tradition. In addition to marking the rank and power of certain individuals in Etruscan culture, warfare was a considerable economic boon to Etruscan civilization. Like many ancient societies, the Etruscans conducted campaigns during summer months; raiding neighboring areas, attempting to gain territory and combating piracy as a means of acquiring valuable resources such as land, prestige goods and slaves. It is also likely individuals taken in battle would be ransomed back to their families and clans at high cost. Prisoners could also potentially be sacrificed on tombs to honor fallen leaders of Etruscan society, not unlike the sacrifices made by Achilles for Patroclus.

Etruscan cities were a group of ancient settlements that shared a common Etruscan language and culture, even though they were independent city-states. They flourished over a large part of the northern half of Italy starting from the Iron Age, and in some cases reached a substantial level of wealth and power. They were eventually assimilated first by Italics in the south, then by Celts in the north and finally in Etruria itself by the growing Roman Republic.

The Etruscan names of the major cities whose names were later Romanised survived in inscriptions and are listed below. Some cities were founded by Etruscans in prehistoric times and bore entirely Etruscan names. Others, usually Italic in origin, were colonised by the Etruscans, who in turn Etruscanized their name.

The estimates for the populations of the largest cities (Veii, Volsinii, Caere, Vulci, Tarquinia, Populonia) range between 25,000 and 40,000 each in the 6th century BC.

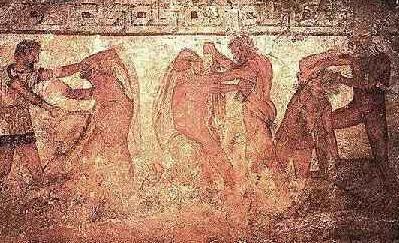

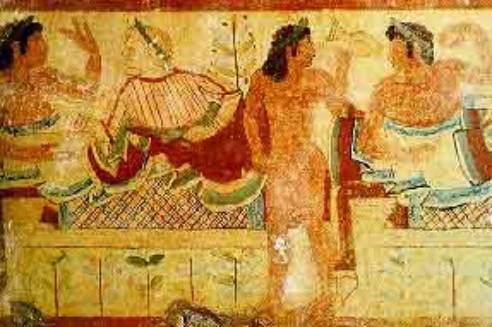

Without doubt the greatest artistic legacy of the Etruscans is their magnificent tomb wall paintings which give a unique and technicolor glimpse into their lost world. Only 2% of tombs were painted, which indicates only the elite could afford such luxury. The paintings are applied either directly to the stone wall or onto a thin base layer of plaster wash with the artists first drawing outlines using chalk or charcoal. The use of shading is minimal, but the colour shades many so that the pictures stand out vibrantly.

The earliest date to the mid-6th century BCE, but topics remain consistent over the centuries with a particular love of dancing, music, hunting, sports, processions, and dining scenes. Sometimes there are also historical scenes such as the battles depicted in the Francois Tomb at Vulci. The paintings give us not only an idea of Etruscan daily life, eating habits, and clothing but also reveal social attitudes, notably to slaves, foreigners, and women. For example, the presence of married women at banquets and drinking parties (indicated by accompanying inscriptions) shows that they enjoyed a more equal social status with their husbands than seen in other ancient cultures of the period.

Pottery was another area of expertise. Bucchero is the indigenous pottery of Etruria and has a distinctive, almost black glossy finish. Produced from the early 7th century BCE, the style often imitated embossed bronze vessels. Popular shapes include bowls, jugs, cups, utensils, and anthropomorphic vessels. Bucchero wares were commonly placed in tombs and were exported widely throughout Europe and the Mediterranean. Another later specialisation was the production of terracotta funerary urns which had a half-life-size figure of the deceased on the lid sculpted in the round. These were painted, and although sometimes a little idealised, they, nevertheless, present a realistic portraiture. The sides of these square urns are often decorated with relief sculpture showing scenes from mythology.

Bronze work had been another Etruscan speciality dating back to the Villanovan period. All manner of daily items were made in the material, but the artist's hand is best seen in small statuettes and, particularly, bronze mirrors which were decorated with engraved scenes, again, usually from mythology. Finally, large-scale metal sculpture was produced of exceptional quality. Very few examples have survived, but those that do, notably the Chimera of Arezzo, are testimony to the imagination and skill of the Etruscan artist.

Etruscan Statues show some of the best examples of the energy and excitement that characterize Etruscan art. Bright paint, swelling contours, animated faces, and gesticulations distinguish the statues. The statue at left is Apulu (Apollo) from the roof of the Portonaccio Temple in Veii, Italy. It is believed to have been made around 510-500 B.C. and is 5 feet 11 inches tall. Notice the rippling folds of his garment and the way the statue leans into its forward movement. In comparison to the statue at right which is a Greek statue of Apollo made in 460 B. C. The Greek statue is much more calm looking, as if he is going to be in motion rather than in the process of movement.

Mythological figures are extremely uncommon in murals found in tombs. The most common theme is of banqueting couples with servants serving the meal and musicians playing. The people in the murals all are making exaggerated gestures. The next most common theme is that of Etruscans enjoying nature. One mural depicts youthful hunters aiming slingshots at colorful birds.

Etruscan Pottery followed closely the style of Greek pottery , but the people were more lively much like the statues. One type of pottery that seems to be very unique to Etruscans is bucchero. It became common in the between the seventh and fifth century B.C. and is black and shiny from polishing. The black color was made by firing in an atmosphere charged with carbon monoxide instead of oxygen. Many people believe that bucchero was made to look like silver pots but were for those that couldn't afford the price of silver. However, bucchero is believed to have been almost as expensive as silver.

The Etruscans were the masters of bronze sculpture and were praised by the Greeks and Romans for their skill. Sadly we have only a few examples of the Etruscans skill with bronze because after Rome occupied the area many of the bronze statues were sent to Rome to be melted down and made into bronze coins. The statues like much of Etruscan art are characterized by their lively features. One vivid example of the Etruscans artistry is the Chimera of Arezzo shown at right. The Chimera is a Greek monster with a lion's head and body and a serpent's tail. A second head of a goat grows out of the left side of the body. This statue is made in the action of attack, the skin is stretched tightly over the muscles and it looks up into the face of an unseen adversary.

The religion of the Etruscans was polytheistic with gods for all those important places, objects, ideas, and events, which were thought to affect or control everyday life. At the head of the pantheon was Tin, although like most such figures he was probably not thought to concern himself much with mundane human affairs. For that, there were all sorts of other gods such as Thanur, the goddess of birth; Aita, god of the Underworld; and Usil, the Sun god. The national Etruscan god seems to have been Veltha (aka Veltune or Voltumna) who was closely associated with vegetation. Lesser figures included winged females known as Vanth, who seem to be messengers of death, and heroes, amongst them Hercules, who was, along with many other Greek gods and heroes, adopted, renamed and tweaked by the Etruscans to sit alongside their own deities.

The two main features of the religion were augury (reading omens from birds and weather phenomena like lightning strikes) and haruspicy (examining the entrails of sacrificed animals to divine future events, especially the liver). That the Etruscans were particularly pious and preoccupied with destiny, fate and how to affect it positively was noted by ancient authors such as Livy, who famously described them as "a nation devoted beyond all others to religious rites". Priests would consult a body of (now lost) religious texts called the Etrusca disciplina. The texts were based on knowledge given to the Etruscans by two divinities: the wise infant Tages, grandson of Tin, who miraculously appeared from a field in Tarquinia while it was being ploughed, and the nymph Vegoia (Vecui). The Etrusca disciplina dictated when certain ceremonies should be performed and revealed the meaning of signs and omens.

Such ceremonies as animal sacrifices, the pouring of blood into the ground, and music and dancing usually occurred outside temples built in honour of particular gods. Ordinary folk would leave offerings at these temple sites to thank the gods for a service done or in the hope of receiving one in the near future. Votive offerings were, besides foodstuffs, typically in the form of inscribed pottery vessels and figurines or bronze statuettes of humans and animals. Amulets were worn, especially by children, for the same reason and to keep away evil spirits and bad luck. The presence of both precious and everyday objects in Etruscan tombs is an indicator of a belief in the afterlife which they considered a continuation of the person's life in this world, much like the ancient Egyptians. If the wall paintings in many tombs are an indicator, then the next life, at least for those occupants, started with a family reunion and rolled on to an endless round of pleasant banquets, games, dancing, and music.

| Etruscan Deity | Other Equiv. | Comments |

| Aita,Eita | Pluto | Ruler of the dead & personification of the underworld. Wolf's head from Greek Hades |

| Aivas, Eivas, Evas | Ajax | aivas tlamunus, aivas vilates - Terror " |

| Ani | Janus | God of Beginnings. Sky god (North) Note: Ani/Ana (male/female) |

| Apollo |

Weather God:Thunder and lightning. Wears laurel Wreath, holds staff & laurel twig. |

|

| Artumes/Artimi | Artemis | Goddess of night and death, Growth in nature. |

| Atuns | Adonis | Rebirth God. *(Boy, Oracle, Voice of the Gods.) Consort for Turan |

| Cautha, Cath | Sun god. Often shown rising from the ocean. | |

| Cel,Cilens | Celens | Equivalent of Greek Gaia. Ati/Apa Cel: Mother/ Father Earth |

| Charontes | Etruscan demons of death. Name suggests a connection with Charun/Charon. | |

| Cul, Culsu | Culsu: The Etruscan demoness: guards the underworld. Torch & scissors. | |

| Evan | Goddess of personal immortality, belongs to the Lasa | |

| Ethausva | Winged Lady in service to Tinia | |

| Februus | Purification, Initiation & the dead. Associated with February | |

| Feronia | Etruscan Goddess who protects freedmen, associated with woodlands, fire & fertility. | |

| Fufluns, (Pacha?) | Bacchus | God of wine, Rebirth, Spring. Wild Nature. Fertility.Son of the earth-goddess Semia. |

| Horta | Goddess of Agriculture | |

| Herc/Horacle/Hercle | Heracles | Strength & Water |

| Karun/Charun | Charon | Demon of death; Blue Demon? With Red hair and snake, feathered wings and an axe or hammer. Or human with red hair & beard. |

| Laran | God of war. Youth with helmet and spear | |

| The Lasa: Alpan, Evan, Racuneta & Vecu | Female deities, guardians of graves. Attributes: mirrors & wreaths. | |

| Lasa Vecu | Nymph Vegoia | Prophesy |

| Leinth | Faceless goddess. Waits at the Gates of the Underworld with Eita | |

| Letham/Lethans | Protector, lives in Eita (underworld) | |

| Lusna, Losna | Moon Goddess | |

| Mania & Mantus | Guardians of the underworld. Mantus is associated with the city Mantua | |

| Maris | Mars | Agriculture. Fertility. Savior God. |

| Menrva | Minerva | Goddess of Wisdom & the arts. Born from the head of Tinia |

| Nethuns | Neptune | God of Water & Moisture.Trident,anchor seahorse,dolphins |

| Nortia | Fortuna | Goddess of fate and fortune. At the beginning of the New Year a nail was driven into a wall in her sanctuary as a fertility rite. |

| Persipnei/Ferspnai | Persephone/ Prosperpine | Queen of the Underworld. |

| Satres | Saturn | God of time and necessity. Old man carrying a sickle and hour glass. sand |

| Selva | Silvanus | Earth God,Woodlands |

| Semla | Semele | Mother of Atuns. In common Mother and child motif. |

| Sethlans, Velchans | Vulcan | Axe God. Fire, the Forge |

| Silenus | Silenus | The Satyr. *Wild Nature" |

| Tarchies,Tages | Boy, Oracle, Voice of the Gods. Appeared from ploughed field. 2 snakes for legs | |

| Tecum | God of the Lucomones(Ruling class) | |

| Thalna | Winged Lady. Lover of Tinia. Goddess associated with childbirth | |

| Thesan | Aurora | Goddess of the Dawn, Childbirth |

| Thethlumth | Underworld deity, fate | |

| Tuchulcha | Grotesque demon. Horse's ears, a vulture's beak and snakes in his hands. | |

| Thufltha(s) | A fury: Inflicts punishment on behalf of Tins | |

| Tinia - Tins | Jupiter | Supreme God. Sky god.With Uni, & Menrva forms a triad of gods. Attributes: Lightning bolts, spear and a scepter. |

| Tiv(r) | Moon deity (cf Germanic Tiw) | |

| Tluscva (Tellus and Tellumo) | Tellus and Tellumo, Earth mother and father. | |

| Turan | Venus | Goddess of love, health & fertility, Goddess of the city Vulci. Usually portrayed as a young woman with wings on her back. Attributes: Pigeon and black swan. Accompanied by the Lasas. Wife of Maris. |

| Turms | Mercury | Trade and Merchandise. Messenger of the Gods. Winged shoes / Heralds staff |

| Turns Aitas | "Hermes of Hades" Leader of the dead. | |

| Tvath | Demeter | Goddess of Resurrection, Love for the Dead |

| Uni | Juno | The supreme goddess. She is the goddess of the cosmos, City goddess of Perugia. Together with her husband Tinia and the goddess Menrva she forms a triad. Mother of Hercle (Hercules). |

| Usil | Sun God | |

| Veive | God of revenge: Youth with laurel wreath & arrows in hand. A goat stands next to him. | |

| Vanth | female demon of death. Lives in the underworld. With the eyes on her wings she sees all and is omni-present. Herald of death and can assist a sick person on his deathbed. Attributes:snake,torch & key. | |

| Veltha | Voltumna, Vertumnus | Original God of the Etruscans, Patron of the Etruscan League Centred on the Fanum Voltumnae in Volsinii.God of Change,Seasons. |

| Vetis | Underworld god of death and destruction |

The Etruscans are generally believed to have spoken a non-Indo-European language. Herodotus (c. 400 BC) records the legend that they came from Lydia (modern western Turkey). Contrarily, Dionysius of Halicarnassus (c. 100 BC) pronounced that the Etruscans were indigenous to Italy, calling themselves Rasenna and being part of an ancient nation "which does not resemble any other people in their language or in their way of life, or customs." Knowledge of the Etruscan language only began with the discovery of the bilingual Phoenician-Etruscan Pyrgi Tablets found at the port of Caere in 1964, and this knowledge is still incomplete.

Some researchers have proposed that the non-Greek inscriptions found on the island of Lemnos, appearing to be related to the Etruscan language and dated to the sixth century BC, support Herodotus' hypothesis. However, recent research, referencing burial rituals, shows that there was no break in practices from the earlier settlements of the Villanovan culture to the Etruscans, indicating that they were likely indigenous after all.

The disciplina etrusca seems to have comprised three categories of books of fate. The first was that of the libri haruspicini, which dealt with divination from the livers of sacrificed animals; the second, the libri fulgurates, on the interpretation of thunder and lightning; the third, the libri rituales, which covered a variety of matters. They contained, as Festus says, "prescriptions concerning the founding of cities, the consecration of altars and temples, the inviolability of ramparts, the laws relating to city gates, the division into tribes, curiae and centuriae, the constitution and organization of armies, and all other things of this nature concerning war and peace.

Among the libri rituales were also three further categories: the libri fatales, on the division of time and the life-span of individuals and peoples; the libri Acherontici, on the world beyond the grave and the rituals for salvation; and finally, the ostentaria, which gave rules for interpreting signs and portents and laid down the propitiatory and expiatory acts needed to obviate disaster and to placate the gods.

So complex and all-embracing a doctrine naturally required long and laborious study. For this, the Etruscans had special training institutes, among which that at Tarquinii early enjoyed the highest repute.

These institutes were much more than priests' seminaries in the modern sense. To judge by their range of studies they were a kind of university with several faculties. For their curricula included not only religious laws and theology, but also the encyclopaedic knowledge required by the priests, which ranged from astronomy and meteorology through zoology, ornithology, and botany to geology and hydraulics.

The last subject was the specialty of the aquivices who advised the city-states on all their hydraulic engineering projects. They were expert diviners who knew how to find subterranean water and how to bore wells, how to dig water channels, supply drinking water in the towns, and install irrigation and drainage systems in the fields. In addition they could create artificial reservoirs and they collaborated with other priests who specialized in constructing subterranean corridors and tunneling mountains.

In Etruria, as in the ancient East, theological and secular knowledge were not separated. Whatever man set himself to do on earth must be in consonance with the cosmos. Thus all the efforts of the priests were directed upon the heavens when it was necessary to discover the will of the gods in accordance with the sacred doctrine.

The orientation and division of space were of crucial importance as much in divination from an animal's liver as in laying the foundation of a temple, in interpreting a shooting star as in surveying land and marking out a garden and field.

The Etruscans attributed great importance to the cult of the dead, because it was also a means of asserting the prestige and power of a family. We can distinguish different periods in this cult and its development is also reflected in the typologies of the necropolises. In the earliest times, the Etruscans were closely attached to the conception of the continuation of a vital activity by the deceased after death.

The tomb was thus built like a house and given furnishings and decorations, both real and reproduced in miniature. Sometimes the walls were frescoed with scenes from daily life or the most important, serene and pleasant moments in the deceased's life. In the same way, cornices, beams, ceilings and frontons, intended to reconstruct the home environment, were painted or sculpted in the rock.

The most ancient examples of monumental tombs were built on the model of the dwelling then in use: a hut with a round or oblong floor-plan. These circular tombs were built using large blocks of stone and covered with a false dome obtained from the progressive inward projection of the rows of blocks until a last slab closed the roof. Access to the sepulchral chamber was through a short corridor where offerings of food or furnishings were often placed. When this type of tomb was abandoned, tombs excavated underground, first of all with a single room and then with several chambers, were used.

The tombs excavated completely underground, generally in hillsides, are defined as "hypogeal" tombs, while those excavated in flat land and covered by soil and gravel are known as "tumuli". This new type was characterized by a central chamber accessible from a long passage beyond which there were other chambers. The floor-plan could be very complex with a passageway, lateral chambers and a central hall with columns and benches.

At times, the tumuli assumed monumental dimensions, with a diameter of over 90 feet and they contained various tombs of members of the same family. Examples of the first period can be seen in Cerveteri and can be linked to the evolution of the dwelling typologies contemporary with the necropolis (second half of the 7th century BC) when houses were divided into two or three rooms flanked and preceded by a sort of vestibule or built around a central courtyard.

From the mid 6th century BC and throughout the 5th century BC, there was another change in the plans of the necropolises. The new tombs were called "cubes" and were built side by side in rows, forming real cities of the dead with streets and squares. Inside the tombs there were only two chambers, and outside there were lateral steps leading to the top of the cube where there were altars for worship. This change reflects a profound modification in the social structure, with the establishment of a non-aristocratic class encouraging less ostentatious houses. Furthermore, due to the influence of the Greek world, the basic conceptions regarding the destiny of the dead had also undergone a change. The primitive faith in the "survival" of the deceased in their tombs had been replaced by the idea of a "kingdom of the dead", imagined along the model of the Greek Avernus.

In 2012, a group of archaeologists were digging at a site in Italy in the hopes of rediscovering a lost Etruscan tomb, known as the Tomb of the Sun and Moon, that had once been a popular tourist destination in the 18th and 19th century. Unfortunately, they were not successful, but their failure led to them to discover something else - the Tomb of the Silver Hands. So what is this tomb and how did it get this unusual name?

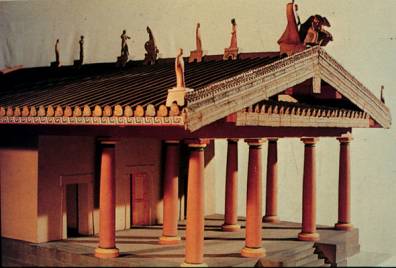

The most ambitious architectural projects of the Etruscans were temples built in a sacred precinct where they could make offerings to their gods. Starting with dried mud-brick buildings using wooden poles and thatch roofs the temples, by c. 600 BCE, had gradually evolved into more solid and imposing structures using stone and Tuscan columns (with a base but no flutes). Each town had three main temples, as dictated by the Etrusca disciplina. Much like Greek temples in design, they differed in that usually only the front porch had columns and this extended further outwards than those designed by Greek architects. Other differences were a higher base platform, a three-room cella inside, a side entrance, and large terracotta roof decorations. These latter were first seen in the buildings of the Villanovan culture but now became much more extravagant and included life-size figure sculpture such as the striding figure of Apollo from the c. 510 BCE Portonaccio Temple at Veii.

Private houses from the early 6th century BCE have multiple intercommunicating rooms, sometimes with a hall and a private courtyard, all on one floor. Roofs are gabled and supported by columns. They had an atrium, an entrance hall open to the sky in the centre and with a shallow basin on the floor in the middle for collecting rainwater. Opposite was a large room, with a hearth and cistern, and side rooms including accommodation for servants.

The burial practices of the Etruscans were by no means uniform across Etruria or even over time. A general preference for cremation eventually gave way to inhumation and then back to cremation again in the Hellenistic period, but some sites were slower to change. It is the burial of members of the same family over several generations in large earth-covered tombs or in small square buildings above ground that are, in fact, the Etruscan's greatest architectural legacy. Some circular tombs measure as much as 40 metres in diameter. They have corbelled or domed ceilings and are often accessed by a stone-lined corridor. The cube-like structures are best seen in the Banditaccia necropolis of Cerveteri. Each has a single doorway entrance, and inside are stone benches on which the deceased were laid, carved altars, and sometimes stone seats were set. Built in orderly rows, the tombs indicate a greater concern with town-planning at that time.

Because of the materials the Etruscans used to build their temples we only have the foundations, and Vitruvius' account of the temples designs. The representative Etruscan temple resembles the Greek gable-roofed temple, but was made of wood and sun-dried brick with terracotta decoration instead of stone. The Etruscan temple had columns only on one side, which created a porch-like entrance, which set this side off as the temple's front, which was unlike the Greek temple. The Etruscan temple was mainly used to house statues of Etruscan God's. Statues made of terracotta were also placed on the peak of the Etruscan temple roof. The picture below is a model of what we believe an Etruscan Temple would have looked like.

The Etruscans believed in predestination. Although a postponement is sometimes possible by means of prayer and sacrifice, the end is certain. According to the libri fatales as described by Censorinus, Man had allocated to him a cycle of seven times twelve years. Anyone who lived beyond these years, lost the ability to understand the signs of the Gods. The Etruscans also believed the existence of their people was also limited by a timescale fixed by the gods. According to the doctrine, ten saecula were allotted to the Etruscan name. This proved very accurate, and it is often said that the Etruscan people predicted their own downfall.

The basis of Etruscan religion was the fundamental idea that the destiny of man was completely determined by the vagaries of the many deities worshipped by the Etruscans. Every natural phenomenon, such as lightning, the structure of the internal organs of sacrificial animals, or the flight patterns of birds, was therefore an expression of the divine will, and contained a message which could be interpreted by trained priests such as Augurs.

Emerging from this basic concept the Rasenna scrupulously followed a complex code of rituals known by the Romans as the "disciplina etrusca". Even up to the fall of the Roman Empire, the Etruscans were regarded by their contemporaries with great respect for their religion and superstitions.

It may have been the fact that Etruscan religious beliefs and practices were so deep-rooted among the Romans that led to the complete destruction of all Etruscan literature as a result of the advent of Christianity. Arnobius, one of the first Christian apologists, living around 300CE, wrote ,"Etruria is the originator and mother of all superstition".

When the Gothic army under Alaric was approaching Rome, the offer made to Pope Innocent I by Etruscan Haruspices was seriously considered by the senate, but finally rejected. The obvious Eastern Greek influence in Etruscan religion and art from the emergence of the civilisation in the 8th Century CE, can be interpreted either as evidence of the Etruscan origins in Lydia, or as the influence of subsequent Greek settlement in the prosperous region of Etruria. However it is interpreted, the Etruscan religion was fundamentally unique to the region. The Etruscan Religion was, supposedly akin to Christianity and Judaism, a revealed religion. An account of the revelation is given by Cicero.

One day a farmer from Tarquinia, while he was busy working in the fields, ploughing the white land with long and straight furrows, drove his harrow into the ground and saw the body of a young boy coming to the surface. According to the Etruscan tradition the young boy was Tagetes, the wise and worshipped prophet-child whose words were listened to by a crowd of people whose number apparently rose hugely with the passing of time.

Tagetes taught the Etruscans the difficult discipline of haruspicy, the art of divining the future by observing the entrails of sacrificed animals, namely the liver.

The haruspex was a priest highly thought of by this people; he was so important in divining the future that his "profession" outlived the Etruscan civilization itself for centuries, after the latter was absorbed in the Roman civilization.

The Tagetic Books were part of the sacred tradition of the Etruscan people which is famous all over the world for its deep religion: they contained the rules and the indications for better understanding the will and the signs of the divinity, and consequently for behaving through actions such as sacrifices, libations and different rites.

The Etruscan religious literature and particularly those books were greatly successful in the ancient Roman world; they were appreciated especially in the II and III centuries A.D., when similar esoteric doctrines became widespread in opposition to the dawning Christianity.

Other famous volumes are the Vegonic Books, containing the indications dictated by Vegoia, the nymph who dictated the rules to establish the boundaries of fields, real estates and the territory of cities. A short passage was handed down by Tarquitius, a I-century-b.C. writer who had had the possibility of reading some passages of those books in Apollo's temple in Rome, where a copy of them was kept with other "pagan" volumes that were then apparently burnt by Stilicho: this passage relates the famous prophecy of the nine-centuries duration of the Etruscan people and nation.

And this is, in fact, the duration of the period of political independence of the Etruscans, if we consider the time from the Villanovan phase to the beginning of the I century b.C., that is when the Etruscans obtained the civitas, the Roman citizenship.

The relationship the Etruscans had with their divinities was quite different from the one of other peoples in the ancient world: while the Greeks believed the gods lived in their own world, often careless of the human world and accustomed to the same passions and weaknesses of humanity, the Romans had a relationship with gods merely based on juridical rules.

The Romans had a strict series of rules that often consisted of a sort of a mere exchange: if I receive a particular grace I will dedicate this ex-voto to the divinity: this is what some of them seemed to say, similarly to what happens today in the religions of the South and Centre of Italy where it often borders on paganism and fetishism.

On the contrary, the Etruscans had a relationship with the gods based on submission: the divinities lived in the sky or under the ground and it was necessary to understand their will by observing the ostenta, the signs that, through the haruspex and the augur priests, indicated the behavior one had to have.

This sense of deep religiousness, it may be said almost of inferiority towards anything concerning the divine, suggests a feeling of oppression. Every single action of a human being was "controlled" by that particular divinity, similarly to the popular religiousness of the other peoples in ancient Italy, namely the Latins.

Therefore all religious practices, rites, sacrifices, the division of space into "dwellings", each of them inhabited by a particular divinity, were so important in the life and culture of this people that it was admired by the other peoples for its dedication and devotion; on the other side, Christian writers came to deprecating the Etruscan religion, like Arnobius (IV century A.D.) who apparently accused Etruria itself of being the "land of all superstitions".

Though very little of the Etruscans religious literature has survived, we know it contained not only the indications of the divinatory practices but also the rules and the practices concerning the civil, political and military life of this people.

The divinities of the Etruscan pantheon were numerous; some of them, entirely new, were introduced during the profound Hellenization of culture, others were identified with analogue divinities, others preceded the coming of the Greek gods.

In order to know their names and position in the universe, a bronze model of sheep liver can be helpful: it is the famous "Piacenza liver" (II-I century b.C.) divided into specific cells with the inscription of the names of the divinities of the sky such as Tinia (Jupiter) and Uni (Juno), of the sun such as Nethuns (Neptune), of the earth such as Fufluns and Selvans, and of the hell such as Cel, Culsu, Vetis, Cilens, Vanth, Charun (Charon).

We can also remember, among the divinities borrowed from the Hellenic culture, Menerva (Minerva), Aplu (Apollo), Artumes (Artemis), Maris (Mars), Turms (Mercury), Hercle (Hercules). An important divinity was Voltumna, worshipped in a shrine at Orvieto, the ancient Volsinii destroyed by the Romans in 264 BC. it became the federal sanctuary of the Etruscans and, consequently, its god too became the main divinity. Some people suggested he could be identified with Vortumnus, the god worshipped in Rome on the Aventine after the destruction of Volsinii. Maybe the name does not refer to a particular god, but it could be a designation of Tinia, that is Jupiter, the main divinity.

Among the main temples whose ruins can be seen in the province of Viterbo, there is the important temple of Artemis at Tarquinia, in the area of the ancient town - a relief model can be seen in the Archaeological Museum of the town itself where one can also admire the very famous winged horses that are part of the image of our home page.

In the study of temple architecture, the various temples of the ancient Falerii are really important; today they can be admired at Civita Castellana and their finds are kept in the Archaeological Museum of the Agro Falisco situated inside the town itself. Numerous small sacred areas are scattered, throughout Etruria:

We remember the big volcanic-stone cylindrical altar of Grotta Porcina at Vetralla and also all the terraces of the cube- and semi-cube-tombs of the rupestrian necropolis, where Etruscan priests performed the rites and ceremonies in honor to the divinities of the next world and in memory of the dead.

In order to know the procedures of some of these rites, epigraphic sources can be helpful, and particularly two extraordinarily valuable documents: the Capua tile, a big terra-cotta tile with the inscription of the rules for the offering to the gods, and the Zagreb mummy, a book made of inscribed linen rolls reused in Egypt in the I century b.C. to wrap up the body of a dead person.

This mummy was taken to the West by a XIX-century merchant and precisely in the Croatian town towards the half of last century, but its importance was recognized only at the end of that century. The book arrived in Egypt with a group of Etruscans (maybe coming from Romanized northern Etruria) who went to Africa (a Roman colonial territory too) looking for a better life.

The linen bands show the black-ink inscription of a sort of religious feast-days calendar, offers and prayers that had to be dedicated time after time to the divinity of a particular day. Not all the text has been understood.

The Etruscan people, therefore, has amazed its contemporaries with their meticulous, respectful and accurate religious rites and they continue to amaze us today for the complexity of their sacred world and maybe for the strong spirituality emanated by the ancient sepulchres, the places of living and the sacred grounds of our forefathers.

The Romans not only grabbed what lands and treasures they could from their neighbors but also stole quite a few ideas from the Etruscans. The Romans adopted the Etruscan practice of divination (itself an adaptation of Near Eastern practices) along with other features of Etruscan religion such as rituals for establishing new towns and dividing territories, something they would receive ample practice opportunities for as they expanded their empire. Also, Etruscan soothsayers and diviners became a staple member of elite households and army units, acknowledged as they were as the Mediterranean's experts in such matters.

The Tuscan column, arched gate, private villa with atrium, tombs with niches for multiple funerary urns, and large-scale temples on impressive raised stepped platforms are all Etruscan architectural features the Romans would adopt and adapt. Other cultural influences include the victory procession which would become the Roman triumph and the Etruscan robe in white, purple or with a red border, which would become the Roman toga. Finally, in language, the Etruscans passed on many words to their successors in Italy, and through their alphabet, itself adapted from Greek, they would influence northern European languages with the creation of the Runic script.