The medicine of the ancient Egyptians is some of the oldest documented. From the beginnings of the civilization in the c. 33rd century BC until the Persian invasion of 525 BC, Egyptian medical practice went largely unchanged and was highly advanced for its time, including simple non-invasive surgery, setting of bones and an extensive set of pharmacopoeia. Egyptian medical thought influenced later traditions, including the Greeks.

Until the 19th century, the main sources of information about ancient Egyptian medicine were writings from later in antiquity. Homer c. 800 BC remarked in the Odyssey: "In Egypt, the men are more skilled in medicine than any of human kind" and "the Egyptians were skilled in medicine more than any other art".

The Greek historian Herodotus visited Egypt around 440 BC and wrote extensively of his observations of their medicinal practices. Pliny the Elder also wrote favorably of them in historical review. Hippocrates (the "father of medicine"), Herophilos, Erasistratus and later Galen studied at the temple of Amenhotep, and acknowledged the contribution of ancient Egyptian medicine to Greek medicine.

In 1822, the translation of the Rosetta stone finally allowed the translation of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions and papyri, including many related to medical matters (Egyptian medical papyri). The resultant interest in Egyptology in the 19th century led to the discovery of several sets of extensive ancient medical documents, including the Ebers papyrus, the Edwin Smith Papyrus, the Hearst Papyrus, the London Medical Papyrus and others dating back as far as 3000 BC.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus (see below) is a textbook on surgery and details anatomical observations and the "examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis" of numerous ailments It was probably written around 1600 BC, but is regarded as a copy of several earlier texts. Medical information in it dates from as early as 3000 BC. Imhotep in the 3rd dynasty is credited as the original author of the papyrus text, and founder of ancient Egyptian medicine. The earliest known surgery was performed in Egypt around 2750 BC.

The Ebers Papyrus (see below) c. 1550 BC is full of incantations and foul applications meant to turn away disease-causing demons, and also includes 877 prescriptions. It may also contain the earliest documented awareness of tumors, if the poorly understood ancient medical terminology has been correctly interpreted. Other information comes from the images that often adorn the walls of Egyptian tombs and the translation of the accompanying inscriptions.

Advances in modern medical technology also contributed to the understanding of ancient Egyptian medicine. Paleopathologists were able to use X-Rays and later CAT Scans to view the bones and organs of mummies. Electron microscopes, mass spectrometry and various forensic techniques allowed scientists unique glimpses of the state of health in Egypt 4000 years ago.

Other documents as the Edwin Smith papyrus (1550 BC), Hearst papyrus (1450 BC), and Berlin papyrus (1200 BC) also provide valuable insight into ancient Egyptian medicine. The Edwin Smith papyrus for example mentioned research methods, the making of a diagnosis of the patient, and the setting of a treatment. It is thus viewed as a learning manual. Treatments consisted of ailments made from i.e. animal, vegetable or fruit substances or minerals.

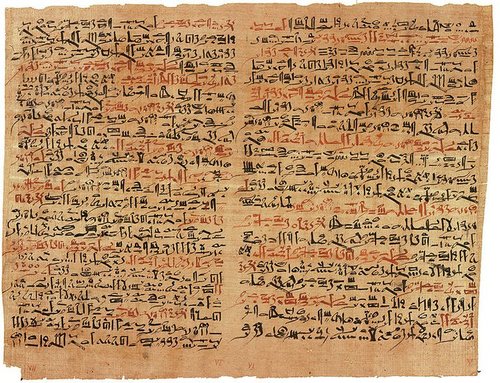

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an Ancient Egyptian medical text on surgical trauma. It dates to Dynasties 16-17 of the Second Intermediate Period in Ancient Egypt, ca. 1600 BCE. The Edwin Smith papyrus is unique among the medical papyri that survive today. While other papyri, such as the Ebers Papyrus and London Medical Papyrus, are medical texts based in magic, the Edwin Smith Papyrus presents a rational and scientific approach to medicine in Ancient Egypt.

The Edwin Smith papyrus is 4.68 m in length, divided into 17 pages. The recto, the front side, is 377 lines long, while the verso, the backside, is 92 lines long. Aside from the fragmentary first sheet of the papyrus, the remainder of the papyrus is fairly intact.

It is written in hieratic, the Egyptian cursive form of hieroglyphs, in black and red ink. The vast majority of the papyrus is concerned with trauma and surgery. On the recto side, there are 48 cases of injury. Each case details the type of the injury, examination of the patient, diagnosis and prognosis, and treatment.The verso side consists of eight magic spells and five prescriptions. The spells of the verso side and two incidents in Case 8 and Case 9 are the exceptions to the practical nature of this medical text.

Authorship of the Edwin Smith Papyrus is debated. The majority of the papyrus was written by one scribe, with only small sections written by a second scribe. The papyrus ends abruptly in the middle of a line, without any inclusion of an author.

It is believed that the papyrus is based upon an earlier text from the Old Kingdom. Form and commentary included in the papyrus give evidence to the existence of an earlier document. The text is attributed by some to Imhotep, an architect, high priest, and physician of the Old Kingdom, 3000-2500 BCE,.

The rational and practical nature of the papyrus is illustrated in the 48 cases. The papyrus begins by addressing injuries to the head, and continues with treatments for injuries to neck, arms and torso.[9] The title of each case details the nature of trauma, such as “Practices for a gaping wound in his head, which has penetrated to the bone and split the skull”.

Next, the examination provides further details of the trauma. The diagnosis and prognosis follow the examination. Last, treatment options are offered. In many of the cases, explanations of trauma are included to provide further clarity.

Among the treatments are closing wounds with sutures (for wounds of the lip, throat, and shoulder), preventing and curing infection with honey, and stopping bleeding with raw meat. Immobilization is advised for head and spinal cord injuries, as well as other lower body fractures. The papyrus also describes anatomical observations. It contains the first known descriptions of the cranial sutures, the meninges, the external surface of the brain, the cerebrospinal fluid, and the intracranial pulsations.

The procedures of this papyrus demonstrate an Egyptian level of knowledge of medicines that surpassed that of Hippocrates, who lived 1000 years later. Due to its practical nature and the types of trauma investigated, it is believed that the papyrus served as a textbook for the trauma that resulted from military battles.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus dates to Dynasties 16-17 of the Second Intermediate Period. Egypt was ruled from Thebes during this time and the papyrus is likely to have originated from there. Edwin Smith purchased in Luxor, Egypt in 1862, from an Egyptian dealer named Mustafa Agha.

The papyrus was in the possession of Smith until his death, when his daughter donated the papyrus to New York Historical Society. From 1938 through 1948, the papyrus was at the Brooklyn Museum. In 1948, the New York Historical Society and the Brooklyn Museum presented the papyrus to the New York Academy of Medicine, where it remains today.

The first translation of the papyrus was by James Henry Breasted, with the medical advice of Dr. Arno B Luckhardt, in 1930 Breasted’s translation changed the understanding of the history of medicine. It demonstrates that Egyptian medical care was not limited to the magical modes of healing demonstrated in other Egyptian medical sources. Rational, scientific practices were used, constructed through observation and examination.

From 2005 through 2006, the Edwin Smith Papyrus was on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. James P. Allen, curator of Egyptian Art at the museum, published a new translation of the work, coincident with the exhibition. This was the first complete English translation since Breasted’s in 1930. This translation offers a more modern understanding of hieratic and medicine.

The Ebers Papyrus, also known as Papyrus Ebers, is an Egyptian medical papyrus dating to circa 1550 BC. Among the oldest and most important medical papyri of ancient Egypt, it was purchased at Luxor, (Thebes) in the winter of 1873–74 by Georg Ebers. It is currently kept at the library of the University of Leipzig, in Germany.

The papyrus was written in about 1500 BC, but it is believed to have been copied from earlier texts, perhaps dating as far back as 3400 BC. Ebers Papyrus is a 110-page scroll, which is about 20 meters long.

Along with the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (circa 1800 BC), the Edwin Smith papyrus (circa 1600 BC), the Hearst papyrus (circa 1600 BC), the Brugsch Papyrus (circa 1300 BC), the London Medical Papyrus (circa 1300 BC), the Ebers Papyrus is among the oldest preserved medical documents. The Brugsch Papyrus provides parallel passages to Ebers Papyrus, helping to clarify certain passages of the latter.

The Ebers Papyrus is written in hieratic Egyptian writing and preserves for us the most voluminous record of ancient Egyptian medicine known. The scroll contains some 700 magical formulas and remedies. It contains many incantations meant to turn away disease-causing demons and there is also evidence of a long tradition of empirical practice and observation.

The papyrus contains a "treatise on the heart". It notes that the heart is the center of the blood supply, with vessels attached for every member of the body.

The Egyptians seem to have known little about the kidneys and made the heart the meeting point of a number of vessels which carried all the fluids of the body - blood, tears, urine and semen.

Mental disorders are detailed in a chapter of the papyrus called the Book of Hearts. Disorders such as depression and dementia are covered.

The descriptions of these disorders suggest that Egyptians conceived of mental and physical diseases in much the same way. The papyrus contains chapters on contraception, diagnosis of pregnancy and other gynecological matters, intestinal disease and parasites, eye and skin problems, dentistry and the surgical treatment of abscesses and tumors, bone-setting and burns.

Remedies

Examples of remedies in the Ebers Papyrus include:

Belly: "For the evacuation of the belly: Cow's milk 1; grains 1; honey 1; mash, sift, cook; take in four portions."

Bowels: "To remedy the bowels: Melilot, 1; dates, 1; cook in oil; anoint sick part."

Cancer: Recounting a "tumor against the god Xenus", it recommends "do thou nothing there against".

Clothing: may be protected from mice and rats by applying cat's fat.

Death: Half an onion and the froth of beer was considered "a delightful remedy against death."

Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm): Wrap the emerging end of the worm around a stick and slowly pull it out. (3500 years later, this remains the standard treatment.

Medicinal use of ochre clays: One of the common remedies described in the papyrus is ochre, or medicinal clay. For example, it is prescribed for various intestinal complaints. It is also prescribed for various eye complaints. Yellow ochre is also described as a remedy for urological complaints.

Modern history of the papyrus

Like the Edwin Smith Papyrus, the Ebers Papyrus came into the possession of Edwin Smith in 1862. The source of the papyrus is unknown, but it was said to have been found between the legs of a mummy in the Assassif district of the Theban necropolis.

The papyrus remained in the collection of Edwin Smith until at least 1869 when there appeared, in the catalog of an antiquities dealer, an advertisement for "a large medical papyrus in the possession of Edwin Smith, an American farmer of Luxor." (Breasted 1930)

The Papyrus was purchased in 1872 by the German Egyptologist and novelist Georg Ebers (born in Berlin, 1837), after whom it is named. In 1875, Ebers published a facsimile with an English-Latin vocabulary and introduction, but it was not translated until 1890, by H. Joachim.

Ebers retired from his chair of Egyptology at Leipzig on a pension and the papyrus remains in the University of Leipzig library. An English translation of the Papyrus was published by Paul Ghalioungui. The papyrus was published and translated by different researchers (the most valuable is German edition Grundriss der Medizin der alten Ägypter, and based on this Paul Ghalioungui edition).

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (also Kahun Papyrus, Kahun Medical Papyrus, or UC 32057) is the oldest known medical text of any kind. Dated to about 1800 BCE, it deals with women's health—gynaecological diseases, fertility, pregnancy, contraception, etc.

It was found at El-Lahun by Flinders Petrie in 1889 and first translated by F. Ll. Griffith in 1893 and published in The Petrie Papyri: Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob. The later Berlin Papyrus and the Ramesseum Papyrus IV cover much of the same ground, often giving identical prescriptions.

The text is divided into thirty-four sections, each section dealing with a specific problem and containing diagnosis and treatment; no prognosis is suggested. Treatments are non-surgical, comprising applying medicines to the affected body part or swallowing them. The womb is at times seen as the source of complaints manifesting themselves in other body parts.

The first seventeen parts have a common format starting with a title and are followed by a brief description of the symptoms, usually, though not always, having to do with the reproductive organs. P> The second section begins on the third page, and comprises eight paragraphs which, because of both the state of the extant copy and the language, are almost unintelligible. Despite this, there are several paragraphs that have a sufficiently clear level of language as well as being intact which can be understood.

Paragraph 19 is concerned with the recognition of who will give birth; paragraph 20 is concerned with the fumigation procedure which causes conception to occur; and paragraphs 20-22 are concerned with contraception. Among those materials prescribed for contraception are crocodile dung, 45ml of honey, and sour milk.

The third section (paragraphs 26-32) is concerned with the testing for pregnancy. Other methods include the placing of an onion bulb deep in the patients flesh, with the positive outcome being determined by the odor appearing to the patients nose.

The fourth and final section contains two paragraphs which do not fall into any of the previous categories. The first prescribes treatment for toothaches during pregnancy. The second describes what appears to be a fistula between bladder and vagina with incontinence of urine "in an irksome place."

Spices such as Cumin, Fenugreek and Corriander were used as medicine in Ancient Egypt.

Fundamentally when considering the health of any culture nutrition must be discussed. The Ancient Egyptians were at least partially aware of the importance of diet, both in balance and moderation. Due to Egypt's great endowment of fertile land food production was never a major issue although of course no matter how bounteous the land paupers and starvation still exist.

The main crops for most of ancient Egyptian history were wheat and barley (See Diet). Consumed in the form of loaves which were produced in a variety of types through baking and fermentation, with yeast greatly enriching the nutritional value of the product, one farmer's crop could support an estimated twenty adults. Barley was also used in beer. Vegetables and fruits of many types were widely grown.

Oil was produced from the linseed plant and there was a limited selections of spices and herbs. Meat (sheep, goats, pigs, wild game) was regularly available to at least the upper classes and fish were widely consumed, although there is evidence of prohibitions during certain periods against certain types of animal products; Herodotus wrote of the pig as being 'unclean'.

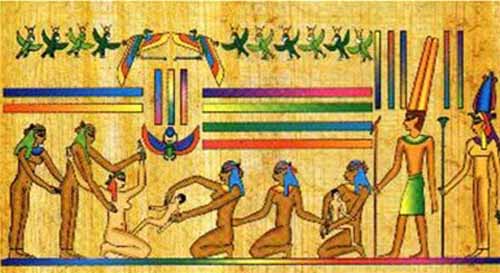

The medical profession of Ancient Egypt had its own hierarchy. At the top was the chief medical officer of Egypt. Under him were the superintendents and inspectors of physicians, and beneath then were the physicians. Egyptian doctors were very advanced in their knowledge of herbal remedies and surgical techniques. Also part of Egyptian medicine were magic, charms, and spells, which had only psychological effects, if any, on a patient.

The ancient Egyptian word for doctor is "wabau". This title has a long history. The earliest recorded physician in the world, Hesy-Ra, practiced in ancient Egypt. He was Chief of Dentists and Physicians to King Djoser, who ruled in the 27th century BC. The lady Peseshet (2400 BC) may be the first recorded female doctor: she was possibly the mother of Akhethotep, and on a stela dedicated to her in his tomb she is referred to as imy-r swnwt, which has been translated as "Lady Overseer of the Lady Physicians."

There were many ranks and specializations in the field of medicine. Royalty employed their own swnw, even their own specialists. There were inspectors of doctors, overseers and chief doctors. Known ancient Egyptian specialists are ophthalmologist, gastroenterologist, proctologist, dentist, "doctor who supervises butchers" and an unspecified "inspector of liquids". The ancient Egyptian term for proctologist, neru phuyt, literally translates as "shepherd of the anus".

Institutions, so called Houses of Life, are known to have been established in ancient Egypt since the 1st Dynasty and may have had medical functions, being at times associated in inscriptions with physicians, such as Peftauawyneit and Wedjahorresnet living in the middle of the first millennium BC. By the time of the 19th Dynasty their employees enjoyed such benefits as medical insurance, pensions and sick leave.

Medical knowledge in ancient Egypt had an excellent reputation, and rulers of other empires would ask the Egyptian pharaoh to send them their best physician to treat their loved ones. Egyptians had some knowledge of human anatomy. For example, in the classic mummification process, mummifiers knew how to insert a long hooked implement through a nostril, breaking the thin bone of the brain case and remove the brain.

They also must have had a general idea of the location in the body cavity of the inner organs, which they removed through a small incision in the left groin. But whether this knowledge was passed on to the practitioners of medicine is unknown and does not seem to have had any impact on their medical theories.

Egyptian physicians were aware of the existence of the pulse and of a connection between pulse and heart. The author of the Smith Papyrus even had a vague idea of a cardiac system, although not of blood circulation and he was unable, or deemed it unimportant, to distinguish between blood vessels, tendons, and nerves. They developed their theory of "channels" that carried air, water and blood to the body by analogies with the River Nile; if it became blocked, crops became unhealthy and they applied this principle to the body: If a person was unwell, they would use laxatives to unblock the "channels".

Quite a few medical practices were effective, such as many of the surgical procedures given in the Edwin Smith papyrus. Mostly, the physicians' advice for staying healthy was to wash and shave the body, including under the arms, and this may have prevented infections. They also advised patients to look after their diet, and avoid foods such as raw fish or other animals considered to be unclean.

1) knives; (2) drill; (3) saw; (4) forceps or pincers; (5) censer; (6) hooks; (7) bags tied with string; (8, 10) beaked vessel; (11) vase with burning incense; (12) Horus eyes; (13) scales; (14) pot with flowers of Upper and Lower Egypt; (15) pot on pedestal; (16) graduated cubit or papyrus scroll without side knot (or a case holding reed scalpels); (17) shears; (18) spoons.

Surgery was a common practice among physicians as treatment for physical injuries. The Egyptian physicians recognized three categories of injuries; treatable, contestable, and untreatable ailments. Treatable ailments the surgeons would quickly set to right. Contestable ailments were those where the victim could presumably survive without treatment, so patients assumed to be in this category were observed and if they survived then surgical attempts could be made to fix them. Surgical tools uncovered in archaeological sites have included knives, hooks, drills, forceps and pinchers, scales, spoons, saws and a vase with burning incense.

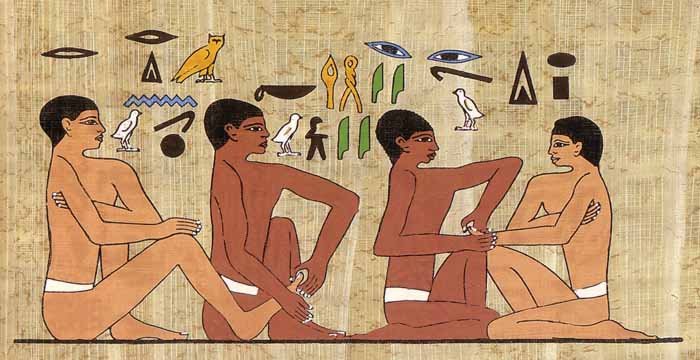

Circumcision of the males was likely the norm although there is little evidence. Though its performance as a procedure was rarely mentioned, the uncircumcised nature of other cultures was frequently noted, the uncircumcised nature of the Liberians was frequently referenced and military campaigns brought back uncircumcised phalli as trophies, which suggests novelty.

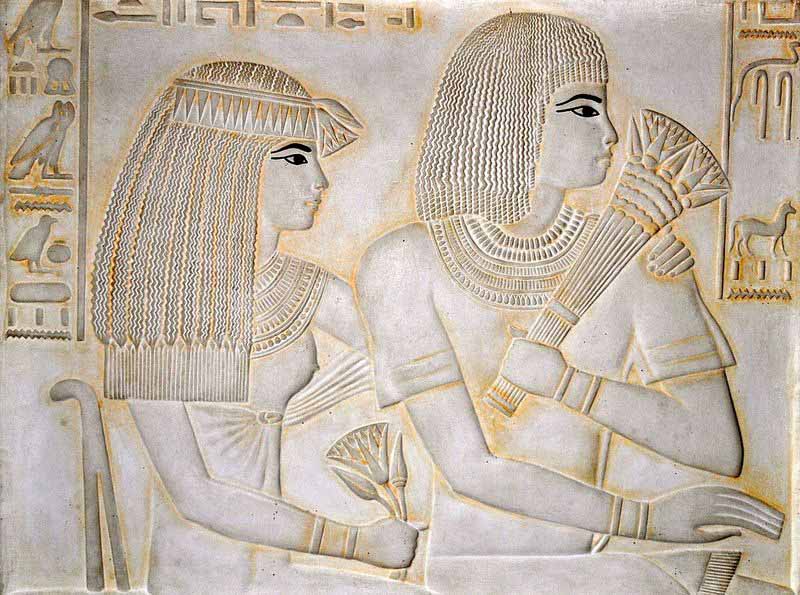

Although other records describe initiates into the religious orders as involving circumcision which would imply that the practice was special and not widespread. The only known depiction of the procedure, in the The Tomb of the Physician, burial place of Ankh-Mahor at Saqquarra, shows adolescents or adults, not babies. Female circumcision may have been practiced, although the single reference to it in ancient texts may be a mistranslation.

Prosthetics, such as artificial toes and eyeballs, were also used; typically, they served little more than decorative purposes. In preparation for burial, missing body parts would be replaced (but these do not appear as if they would have been useful, or even attachable) before death.

The extensive use of surgery, mummification practices, and autopsy as a religious exercise gave Egyptians a vast knowledge of the body's morphology, and even a considerable understanding of organ functions. The function of most major organs were correctly presumed - for example, blood was correctly guessed to be a transpiration medium for vitality and waste which is not to far from its actual role in carrying oxygen and removing carbon dioxide - with the exception of the heart and brain whose functions were switched.

Dentistry was an important field, as an independent profession it dated from the early third millennium BC, although it may not have never been prominent. The Egyptian diet was high on abrasives such as sand left over from grinding grain) and so the condition of their teeth was quite poor, although archaeologists have noted a steady decrease in severity and incidence throughout 4000 BC to 1000 AD probably due to improved grain grinding techniques.

All Egyptian remains have sets of teeth in quite poor states. Dental disease could even be fatal, such as for Djedmaatesankh a musician from Thebes who dies around the age of thirty five from extensive dental diseases and a huge infected cyst. If an individuals teeth escaped being worn down, cavities were rare in consequence of the rarity of sweeteners.

Dental treatment was infective and the best sufferers could hope for was the quick loss of an infected tooth. The Instruction of Ankhsheshonq contains the maxim "There is no tooth that rots yet stays in place". No records document the hastening of this process and no tools suited for the extraction of teeth have been found but some remains show sign of forced tooth removal. Replacement teeth have been found to exist although it is not clear whether or not this is just post-mortem cosmetics. Extreme pain might have been medicated with opium.

Tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

Ruffer (1910) reported the presence of tuberculosis of the spine in Nesparehan, a priest of Amun of the 21st Dynasty. This shows the typical features of Pott's disease with collapse of thoracic vertebra, producing the angular kyphosis (hump-back). A well known complication of Pott's disease is the tuberculous suppuration moving downward under the psoas major muscle, towards the right iliac fossa, forming a very large psoas abscess.(Nunn 1996:64)

Ruffer's report has remained the best authenticated case of spinal tuberculosis from ancient Egypt. All known possible cases, ranging from the Predynastic to 21st Dynasty were reviewed by Morse, Brockwell, and Ucko (1964) as well as by Buikstra, Baker, and Cook.(1993) These included Predynastic specimens collected at Naqada by Petrie and Quibell in 1895 as well as nine Nubian Specimens from the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Both reviewers were in agreement that there was very little doubt that tuberculosis was the cause of pathology in most, but not all, cases. In some cases, it was not possible to exclude compression fractures, osteomyelitis, or bone cysts as causes of death.

The numerous artistic representation of hump-backed individuals are provocative but not conclusive. The three earliest examples are undoubtedly of Predynastic origin. The first is a ceramic figurine reported to have been found by Bedu in the Aswan district. It represents an emaciated human with angular kyphosis of the thoracic spine crouching in a clay vessel.(Schrumph-Pierron 1933) The second possible Predynastic representation with spinal deformity indicative of tuberculosis is a small standing ivory likeness of a human with arms down at the sides of the body bent at the elbows.

The head is modeled with facial features carefully indicated. The figure is shown with a protrusion of the back and on the chest.(Morse 1967: 261) The last Predynastic example is a wooden statue contained within the Brussels Museum. Described as a bearded male with intricate facial features, the figure has a large rounded hunch-back and an angular projection of the sternum.(Jonckheere 1948: 25)

As well, there are several historic Egyptian representations which indicate the possibility of tuberculosis deformity. One of the most suggestive, located in and Old Kingdom 4th Dynasty tomb, is of a bas relief serving girl who exhibits localized angular kyphosis. A second provocative example has its origin in the Middle Kingdom. A tomb painting at Beni Hasan, the representation shows a gardener with a localized angular deformity of the cervical-thoracic spine.(Morse 1967: 263)

Poliomyelitis

A viral infection of the anterior horn cells of the spinal chord, the presence of poliomyelitis can only be detected in those who survive its acute stage. Mitchell (Sandison 1980:32) noted the shortening of the left leg, which he interpreted as poliomyelitis, in the an early Egyptian mummy from Deshasheh. The club foot of the Pharaoh Siptah as well as deformities in the 12th Dynasty mummy of Khnumu-Nekht are probably the most attributable cases of poliomyelitis.

An 18th or 19th Dynasty funerary staele shows the doorkeeper Roma with a grossly wasted and shortened leg accompanied by an equinus deformity of the foot. The exact nature of this deformity, however, is debated in the medical community.

Some favor the view that this is a case of poliomyelitis contracted in childhood before the completion of skeletal growth. The equinus deformity, then, would be a compensation allowing Roma to walk on the shortened leg. Alternatively, the deformity could be the result of a specific variety of club foot with a secondary wasting and shortening of the leg.(Nunn 1996: 77)

Dwarfism:

Dasen (1993) lists 207 known representations of dwarfism. Of the types described, the majority are achondroplastic, a form resulting in a head and trunk of normal size with shortened limbs. The statue of Seneb is perhaps the most classic example. A tomb statue of the dwarf Seneb and his family, all of normal size, goes a long way to indicate that dwarfs were accepted members in Egyptian society. Other examples called attention to by Ruffer (1911) include the 5th Dynasty statuette of Chnoum-hotep from Saqqara, a Predynastic drawing of the "dwarf Zer" from Abydos, and a 5th Dynasty drawing of a dwarf from the tomb of Deshasheh.

Skeletal evidence, while not supporting the social status of dwarfs in Egyptian society, does corroborate the presence of the deformity. Jones described a fragmentary Predynastic skeleton from the cemetery at Badari with a normal shaped cranium both in size in shape. In contrast to this, however, the radii and ulna are short and robust, a characteristic of achondroplasia. A second case outlined by Jones consisted of a Predynastic femur and tibia, both with typical short shafts and relatively large articular ends.

Breasted, J.H. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus

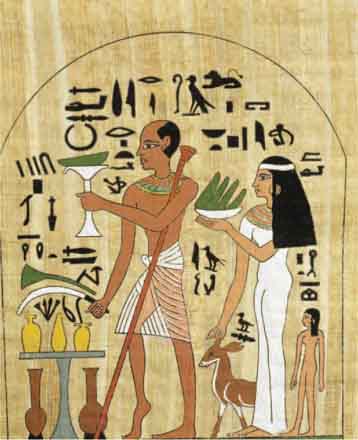

Magic and religion were an integral part of everyday life in ancient Egypt. Evil gods and demons were thought to be responsible for many ailments, so often the treatments involved a supernatural element, such as beginning treatment with an appeal to a deity. There does not appear to have existed a clear distinction between what nowadays one would consider the very distinct callings of priest and physician. The healers, many of them priests of Sekhmet, often used incantations and magic as part of treatment.

The widespread belief in magic and religion may have resulted in a powerful placebo effect; that is, the perceived validity of the cure may have contributed to its effectiveness. The impact of the emphasis on magic is seen in the selection of remedies or ingredients for them. Ingredients were sometimes selected seemingly because they were derived from a substance, plant or animal that had characteristics which in some way corresponded to the symptoms of the patient. This is known as the principle of simila similibus ("similar with similar") and is found throughout the history of medicine up to the modern practice of homeopathy. Thus an ostrich egg is included in the treatment of a broken skull, and an amulet portraying a hedgehog might be used against baldness.

Amulets in general were very popular, being worn for many magical purposes. Health related amulets are classified as homeopoetic, phylactic and theophoric. Homeopoetic amulets portray an animal or part of an animal, from which the wearer hopes to gain positive attributes like strength or speed. Phylactic amulets protected against harmful gods and demons. The famous Eye of Horus was often used on a phylactic amulet. Theophoric amulets represented Egyptian gods; one represented the girdle of Isis and was intended to stem the flow of blood at miscarriage. They were often made of bone, hanging from a leather strap.

A Day In The Life Of An Ancient Egyptian Doctor IFL Science - April 5, 2023

Follow Peseshet as she carries out the day-to-day activities of a doctor in Ancient Egypt, from treating patients to teaching the next generation of students, as outlined by Elizabeth Fox. Peseshet, who lived around 2500 BCE when the pyramids were being built, is considered the earliest known female physician in Ancient Egypt, possibly in history.

Egyptian Papyrus Reveals Rare Details of Ancient Medical Practices Live Science - August 17, 2018

Ancient manuscripts that were previously untranslated have revealed a rare and fascinating glimpse of scientific and medical practices in Egypt thousands of years ago. Experts working with the texts recently discovered that the papyrus scrolls included the oldest known medical discussion of the kidneys, as well as notes on treatments for eye diseases and a description of a pregnancy test, the science news site ScienceNordic reported. The manuscripts are part of the Papyrus Carlsberg Collection, housed at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, where an international team of researchers is collaborating to interpret the unpublished documents

Remains of 'End of the World' Epidemic Found in Ancient Egypt Live Science - June 16, 2014

Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of an epidemic in Egypt so terrible that one ancient writer believed the world was coming to an end. Working at the Funerary Complex of Harwa and Akhimenru in the west bank of the ancient city of Thebes (modern-day Luxor) in Egypt, the team of the Italian Archaeological Mission to Luxor (MAIL) found bodies covered with a thick layer of lime (historically used as a disinfectant). The researchers also found three kilns where the lime was produced, as well as a giant bonfire containing human remains, where many of the plague victims were incinerated. Pottery remains found in the kilns allowed researchers to date the grisly operation to the third century A.D., a time when a series of epidemics now dubbed the "Plague of Cyprian" ravaged the Roman Empire, which included Egypt. Saint Cyprian was a bishop of Carthage (a city in Tunisia) who described the plague as signaling the end of the world.

13 Photos: Ancient Egyptian Skeleton Reveals Earliest Metastatic Cancer Live Science - March 22, 2014

A 3,000-year-old skeleton from a conquered territory of ancient Egypt is now the earliest known complete example of a person with malignant cancer spreading from an organ, findings that could help reveal insights on the evolution of the disease, researchers say. Here, the skeleton (called Skeleton Sk244-8) in its original burial position in a tomb in northern Sudan in northeastern Africa, with a blue-glazed amulet (inset) found buried alongside him; the amulet shows the Egyptian god Bes depicted on the reverse side.

Magic, Medicine Eased Ancient Egyptian Headaches -- Reuters - January 6, 2002

Can't beat that headache? Why not try an incantation to falcon-headed Horus, or a soothing poultice of "Ass's grease"? According to researchers, 3,500-year-old papyri show ancient Egyptians turning to both their gods and medicine to banish headache pain.

"The border between magic and medicine is a modern invention; such distinctions did not exist for ancient healers," explain Dr. Axel Karenberg, a medical historian, and Dr. C. Leitz, an Egyptologist, both of the University of Cologne, Germany.

In a recent issue of the journal Cephalalgia, the researchers report on their study of papyrus scrolls dating from the early New Kingdom period of Egyptian history, about 1550 BC. Ancient Egyptian healers had only the barest understanding of anatomy or medicine. Indeed, while the head was considered the "leader" of the body, the brain itself was considered relatively unimportant--as evidenced by the fact that it was usually discarded during the mummification process.

Headache, that timeless bane of humanity, was usually ascribed to the activity of "demons," the German researchers write, although over time Egyptian physicians began to speculate that problems originating within the body, such as the incomplete digestion of food, might also be to blame.

Once beset with a headache, those living under the pharaohs turned to their gods for help. One incantation sought to evoke the gods' empathy, imagining that even immortals suffered headache pain. "'My head! My head!' said Horus," reads one papyrus. "'The side of my head!' said Thoth. 'Ache of my forehead,' said Horus. 'Upper part of my forehead!' said Thoth." In this way, Karenberg and Leitz write, "the patient is identified with (the gods) Horus and Thoth," the latter being the god of magicians and wise men. The incantation continues with the sun god Ra ordering the patient to recover "up to your temples," while the patient threatens his "headache demons" with terrible punishments ("the trunk of your body will be cut off").

Still, the gods may have ignored the pleas of many patients, who also turned to medicine for relief. According to one ancient text, these included a poultice made of "skull of catfish," with the patient's head being "rubbed therewith for four days." Other prescriptions included stag's horn, lotus, frankincense and a concoction made from donkey called "Ass's grease." Even these remedies could be divinely inspired, however. On one 4,000-year-old scroll, a boastful druggist claims that his headache cure is prepared by the goddess Isis herself.