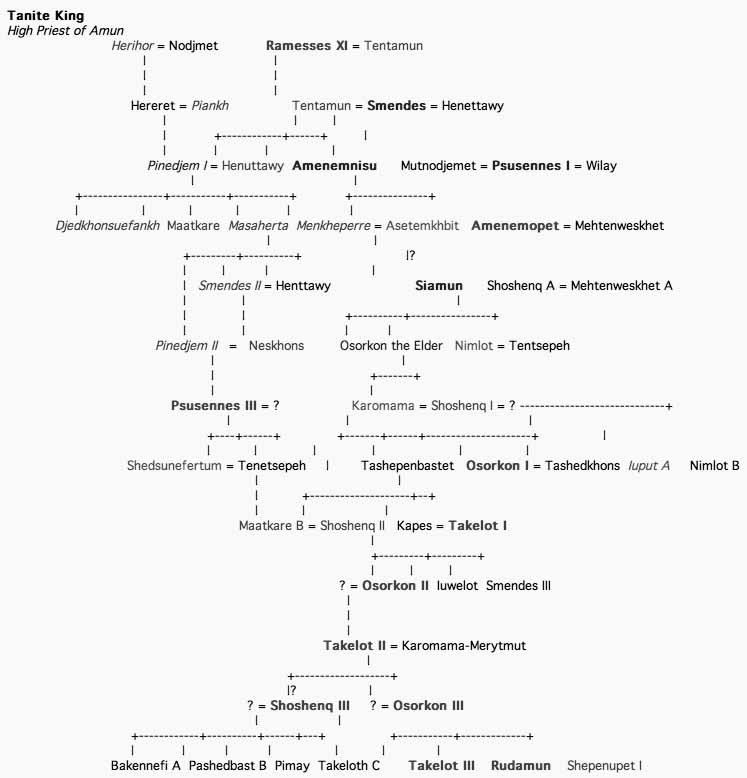

The Twenty-First, Twenty-Second, Twenty-Third, Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, Third Intermediate Period.

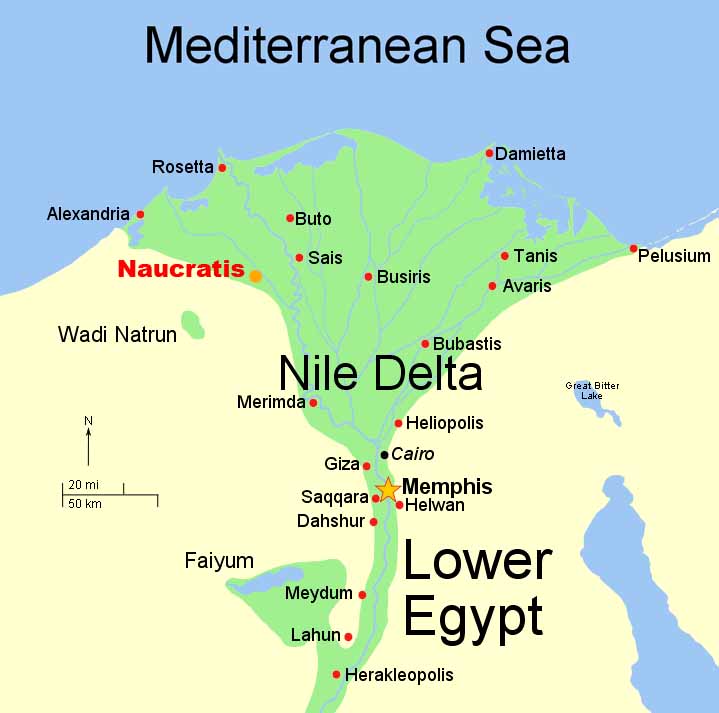

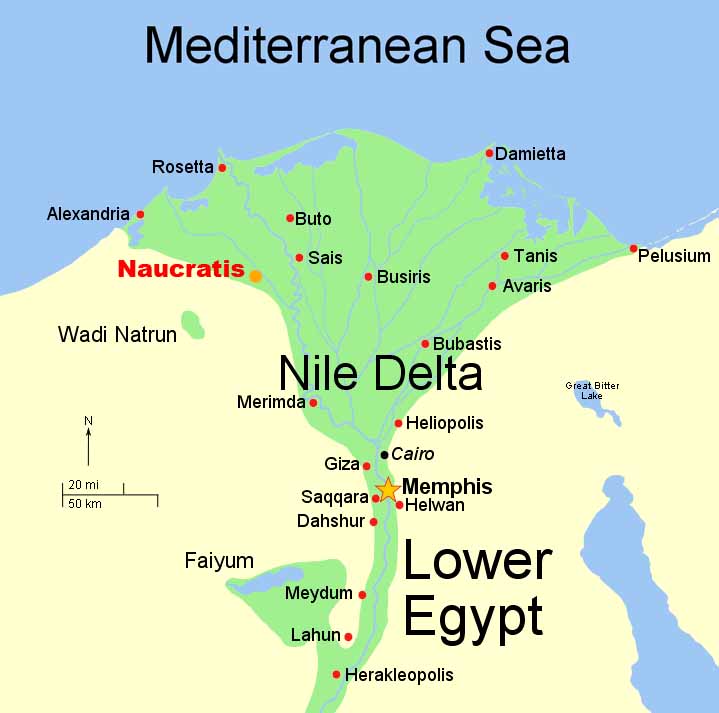

The kings of the Twenty-Second Dynasty of Egypt were a series of Meshwesh Libyans who ruled from circa 943 BC until 720 BC. They had settled in Egypt since the Twentieth Dynasty. Manetho states that the dynasty originated at Bubastis, but the kings almost certainly ruled from Tanis, which was their capital and the city where their tombs have been excavated.

Another king who belongs to this group is Tutkheperre Shoshenq, whose precise position within this dynasty is currently uncertain although he is now thought to have ruled Egypt early in the 9th century BC for a short time.

The so-called Twenty-Third Dynasty was an offshoot of this dynasty perhaps based in Upper Egypt, though there is much debate concerning this issue. All of its kings reigned in Middle and Upper Egypt including the Western Desert Oases. The next ruler at Tanis after Shoshenq V was Osorkon IV but this king is not believed to be a member of the 22nd Dynasty since he only controlled a small portion of Lower Egypt together with Tefnakhte of Sais - whose authority was recognized at Memphis - and Iuput II of Leontopolis.

Hedjkheperre Setepenre Shoshenq I also known as Sheshonk or Sheshonq I was a Meshwesh Berber king of Egypt - of Libyan ancestry - and the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty. Shoshenq I was the son of Nimlot A, Great Chief of the Ma, and his wife Tentshepeh A, a daughter of a Great Chief of the Ma herself. He is perhaps mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as Shishaq.

The conventional dates for his reign as established by Kenneth Kitchen are 945 - 924 BC but his time-line has recently been revised downwards by a few years to 943-922 BC since he may well have lived for up to 2 to 3 years after his successful campaign in Canaan, conventionally dated to 925 BC. There is "no certainty" that Shoshenq's 925 BC campaign terminated just prior to this king's death a year later in 924 BC.

The English Egyptologist, Morris Bierbrier also dated Shoshenq I's accession "between 945-940 BC" in his seminal 1975 book concerning the genealogies of Egyptian officials who served during the late New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period. Bierbrier based his opinion on Biblical evidence collated by W. Albright in a BASOR 130 paper.

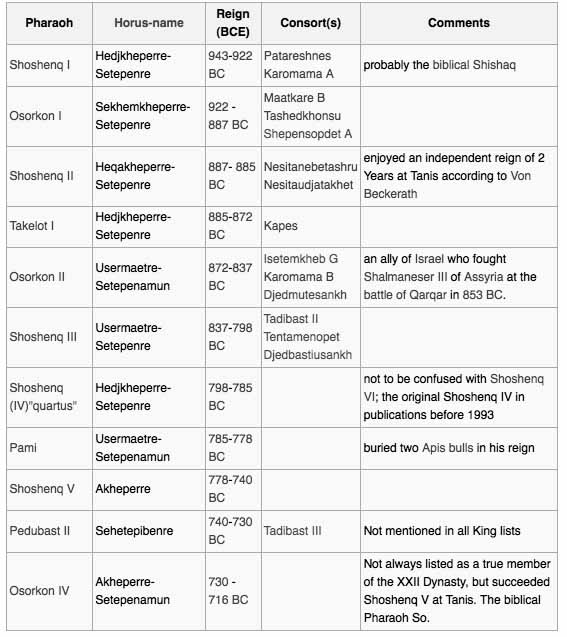

This development would also account for the mostly unfinished state of decorations of Shoshenq's building projects at the Great Temple of Karnak where only scenes of the king's Palestinian military campaign are fully carved. Building materials would first have had to be extracted and architectural planning performed for his great monumental projects here.

Such activities usually took up to a year to complete before work was even begun. This would imply that Shoshenq I likely lived for a period in excess of one year after his 925 BC campaign. On the other hand, if the Karnak inscription was concurrent with Shoshenq's campaign into Canaan, the fact that it was left unfinished would suggest this campaign occurred in the last year of Shoshenq's reign. This possibility would also permit his 945 BC accession date to be slightly lowered to 943 BC.

The most recent and comprehensive study of Ancient Egyptian chronology affirms the theory that Sheshonq I came to power in 943 BC rather than 945 BC as is conventionally assumed based on epigraphic evidence from the Great Dakhla stela, which dates to Year 5 of his reign.

Sheshonk I is frequently identified with the Egyptian king "Shishaq", referred to in the Old Testament at 1st Kings 11:40, 14:25, and 2 Chronicles 12:2-9. According to the Bible, Shishaq invaded Judah, mostly the area of Benjamin, during the fifth year of the reign of king Rehoboam, taking with him most of the treasures of the temple created by Solomon. Shoshenq I is generally attributed with the raid on Judah. This is corroborated with a stela discovered at Megiddo.

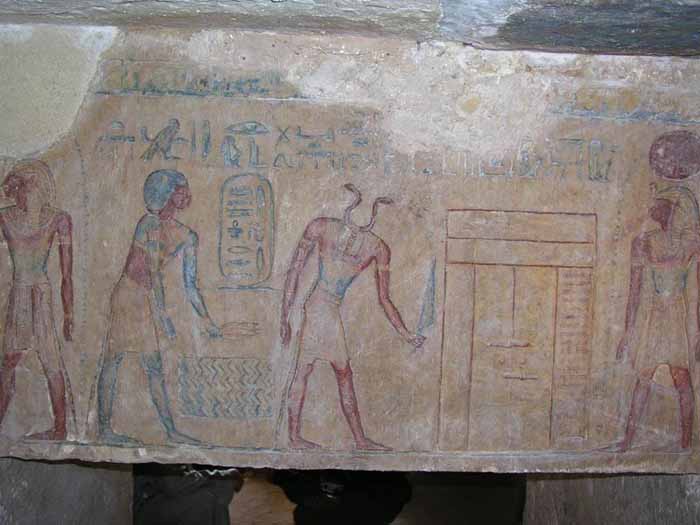

Karnak relief depicting Shoshenq I and

his second son, the High Priest Iuput A

Shoshenq I was the son of Nimlot A and Tentsepeh A. His paternal grandparents were the Chief of the MA Shoshenk (A) and his wife Mehytenweskhet A. Prior to his reign, Shoshenq I had been the Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Army, and chief advisor to his predecessor Psusennes II, as well as the father-in-law of Psusennes' daughter Maatkare.

He also held his father's title of Great Chief of the Ma or Meshwesh, which is an Egyptian word for Berbers of Libya. His ancestors were Libyans who had settled in Egypt during the late New Kingdom, probably at Herakleopolis Magna, though Manetho claims Shoshenq himself came from Bubastis, a claim for which no supporting physical evidence has yet been discovered. Significantly, his Libyan uncle Osorkon the Elder had already served on the throne for at least six years in the preceding 21st Dynasty; hence, Shoshenq I's rise to power was not wholly unexpected.

As king, Shoshenq chose his eldest son, Osorkon I, as his successor and consolidated his authority over Egypt through marriage alliances and appointments. He assigned his second son, Iuput A, the prominent position of High Priest of Amun at Thebes as well as the title of Governor of Upper Egypt and Commander of the Army to consolidate his authority over the Thebaid. Finally, Shoshenq I designated his third son, Nimlot B, as the "Leader of the Army" at Herakleopolis in Middle Egypt.

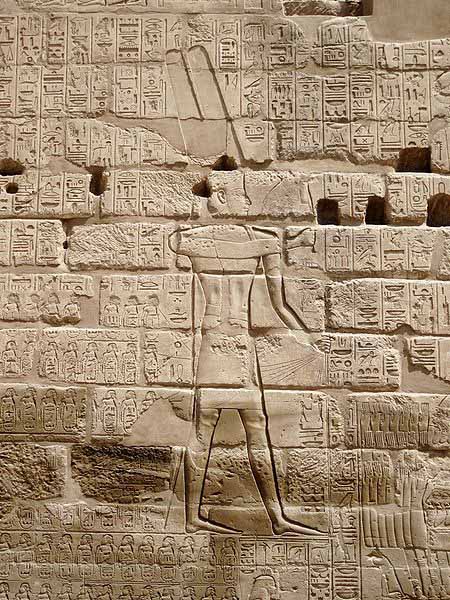

This Karnak temple wall depicts a list of city states conquered

by Shoshenq I in his Near Eastern military campaigns.

He pursued an aggressive foreign policy in the adjacent territories of the Middle East, towards the end of his reign. This is attested, in part, by the discovery of a statue base bearing his name from the Lebanese city of Byblos, part of a monumental stela from Megiddo bearing his name, and a list of cities in the region comprising Syria, Philistia, Phoenicia, the Negev and the Kingdom of Israel, among various topographical lists inscribed on the walls of temples of Amun at al-Hibah and Karnak.

Unfortunately there is no mention of either an attack nor tribute from Jerusalem, which has led some to suggest that Sheshonk was not the Biblical Shishak. The fragment of a stela bearing his cartouche from Megiddo has been interpreted as a monument Shoshenq erected there to commemorate his victory. Some of these conquered cities include Ancient Israelite fortresses such as Megiddo, Taanach and Shechem.

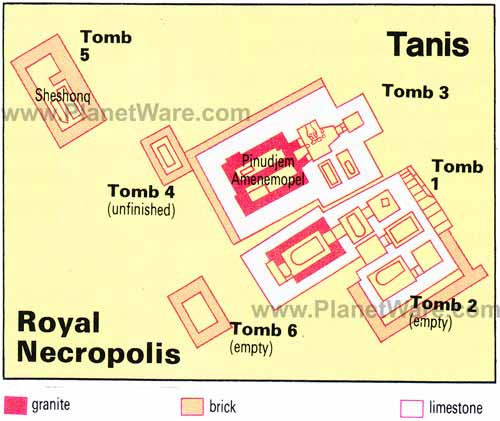

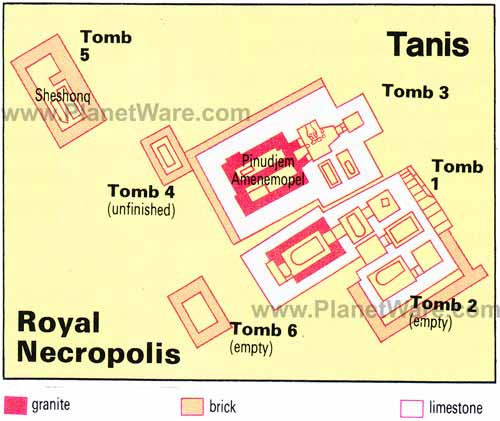

He was succeeded by his son Osorkon I after a reign of 21 Years. According to the British Egyptologist Aidan Dodson, no trace has yet been found of the tomb of Shoshenq I; the sole funerary object linked to Shoshenq I is a canopic chest of unknown provenance that was donated to the Agyptisches Museum, Berlin by Julius Isaac in 1891.

This may indicate his tomb was looted in antiquity, but this hypothesis is unproven. Egyptologists differ over the location of Sheshonq I's burial and speculate that he may have been buried somewhere in Tanis - perhaps in one of the Anonymous royal tombs here - or in Bubastis. However, Troy Sagrillo in a GM 205 (2005) paper observes that "there are only a bare handful of inscribed blocks from Tanis that might name the king (i.e., Shoshenq I) and none of these come from an in situ building complex contemporary with his reign." Hence, it is more probable that Shoshenq was buried in another city in the Egyptian Delta.

Sagrillo offers a specific location for Shoshenq's burial - the Ptah temple enclosure of Memphis Sagrillo concludes by observing that if Shoshenq I's burial place was located at Memphis, "it would go far in explaining why this king's funerary cult lasted for some time at the site after his death."

While Shoshenq's tomb is currently unknown, the burial of one of his prominent state officials at Thebes, the Third Prophet of Amun Djedptahiufankh, was discovered intact in Tomb DB320 in the 19th Century. Inscriptions on Djedptahiufankh's Mummy bandages show that he died in or after Year 11 of this king. His Mummy was discovered to contain various gold bracellets, amulets and precious carnelian objects and give a small hint of the vast treasures that would have adorned Shoshenq I's tomb.

Statue inscribed with the praenomen of Osorkon I discovered at Byblos.

Osorkon bringing offerings

The son of Shoshenq I and his chief consort, Karomat A, Osorkon I was the second king of Egypt's 22nd Dynasty and ruled around 922 BC - 887 BC. He succeeded his father Shoshenq I who probably died within a year of his successful 923 BC campaign against the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

Osorkon I's reign is known for many temple building projects and was a long and prosperous period of Egypt's History. His highest known date is a "Year 33 Second Heb Sed" inscription found on the bandage of Nakhtefmut's Mummy which held a bracellet inscribed with Osorkon I's praenomen: Sekhemkheperre.

This date can only belong to Osorkon I since no other early Dynasty 22 king ruled for close to 30 years until the time of Osorkon II. Other mummy linens which belong to his reign include three separate bandages dating to his Regnal Years 11, 12, and 23 on the mummy of Khonsmaakheru in Berlin.

The bandages are anonymously dated but definitely belong to his reign because Khonsmaakheru wore leather bands that contained a menat-tab naming Osorkon I. Secondly, no other king who ruled around Osorkon I's reign had a 23rd Regnal Year including Shoshenq I who died just before the beginning of his Year 22.

While Manetho gives Osorkon I a reign of 15 Years in his Aegyptiaca, this is most likely an error for 35 Years based on the evidence of the second Heb Sed bandage, as Kenneth Kitchen notes. Osorkon I's throne name - Sekhemkheperre - means "Powerful are the Manifestations of Re."

Although Osorkon I is thought to have been directly succeeded by his son Takelot I, it is possible that another ruler, Heqakheperre Shoshenq II, intervened briefly between these two kings because Takelot I was a son of Osorkon I through Queen Tashedkhons, a secondary wife of this king. In contrast, Osorkon I's senior wife was Queen Maatkare B, who may have been Shoshenq II's mother.

However, Shoshenq II could also have been another son of Shoshenq I since the latter was the only other king to be mentioned in objects from Shoshenq II's intact royal tomb at Tanis aside from Shoshenq II himself. These objects are inscribed with either Shoshenq I's praenomen Hedjkheperre Shoshenq (though this is not certain as it requires reading the objects as a massive hierogylyphic text), or Shoshenq, Great Chief of the Meshwesh, which was Shoshenq I's title before he became king.

Since Derry's forensic examination of his Mummy reveals him to be a Man in his fifties upon his death, Shoshenq II could have lived beyond Osorkon's 35 year reign and Takelot I's 13 year reign to assumed the throne for a few short years. An argument against this hypothesis is the fact that most kings of the period were commonly named after their grandfathers, and not their fathers.

While the British scholar Kenneth A. Kitchen views Shoshenq II to be the High Priest of Amun at Thebes Shoshenq C, and a short-lived coregent of Osorkon I who predeceased his father, the well-respected German Egyptologist Jurgen von Beckerath in his seminal 1997 book, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Agypten, maintains that Shoshenq II was rather an independent king of Tanis who ruled the 22nd Dynasty in his own right for c.2 Years.

von Beckerath's hypothesis is supported by the fact that Shoshenq II employed a complete royal titulary along with a distinct prenomen Heqakheperre and his intact tomb at Tanis was filled with numerous treasures including jewelled pectorals and bracellets, an impressive falconheaded silver coffin and a gold face mask - items which indicate a genuine king of the 22nd Dynasty.

More significantly, however, no mention of Osorkon I's name was preserved on any ushabtis, jars, jewelry or other objects within Shoshenq II's tomb. This situation would be improbable if he was indeed Osorkon I's son, and was buried by his father, as Kitchen's Chronology suggests. These facts, taken together, imply that Sheshonq II ruled on his own accord at Tanis and was not a mere coregent.

Manetho's Epitome states that "3 Kings for 25 years" separate Osorkon I from a Takelot (Takelothis). This could be an error on Manetho's part or an allusion to Shoshenq II's reign. It may also be a reference to the recently discovered early Dynasty 22 king Tutkheperre, whose existence is now corroborated by an architectural block from the Great Temple of Bubastis, where Osorkon I and Osorkon II are well attested monumentally.

Osorkon I's reign in Egypt was peaceful and uneventful; however, both his son and grandson, Takelot I and Osorkon II respectively, later encountered difficulties controlling Thebes and Upper Egypt within their own reigns since they had to deal with a rival king: Harsiese A. Osorkon I's tomb has never been found. [edit]

Heqakheperre Shoshenq II was an Egyptian king of the 22nd dynasty of Egypt. He was the only ruler of this Dynasty whose tomb was not plundered by tomb robbers. His final resting place was discovered within Psusennes I's tomb at Tanis by Pierre Montet in 1939. Montet removed the coffin lid of Shoshenq II on March 20, 1939, in the presence of king Farouk of Egypt himself. It proved to contain a large number of jewel-encrusted bracelets and pectorals, along with a beautiful hawkheaded silver coffin and a gold funerary mask.

The gold facemask had been placed upon the head of the king. Montet later discovered the intact tombs of two Dynasty 21 kings - Psusennes I and Amenemope a year later in February and April 1940 respectively. Shoshenq II's prenomen, Heqakheperre Setepenre, means "The Manifestation of Re rules, Chosen of Re."

There is a small possibility that Shoshenq II was the son of Shoshenq I. Two bracelets from Shoshenq II's tomb mention king Shoshenq I while a pectoral was inscribed with the title 'Great Chief of the Ma Shoshenq,' a title which Shoshenq I employed under Psusennes II before he became king. These items may be interpreted as either evidence of a possible filial link between the two men or just mere heirlooms.

A high degree of academic uncertainty regarding the parentage of this king exists: some scholars today contend that Shoshenq II was actually a younger son of Shoshenq I - who outlived Osorkon I and Takelot I - due to the discovery of the aforementioned items naming the founder of the 22nd Dynasty within his intact royal Tanite tomb.

As the German Egyptologist Karl Jansen-Winkeln observes in the recent (2005) book on Egyptian chronology: "The commonly assumed identification of this king with the (earlier) HP and son of Osorkon I does not appear to be very probable."

A forensic examination of Shoshenq II's body by Dr. Douglas Derry, the head of Cairo Museum's anatomy department, reveals that he was a man in his fifties when he died.Hence, Shoshenq II could have easily survived Osorkon I's 35 year reign and ruled Egypt for a short while before Takelot I came to power. Moreover, Manetho's Epitome explicitly states that "3 Kings" intervened between Osorkon I and Takelot I.

Unfortunately, Manetho's suggested position for these three kings cannot be presently verified due to the paucity of evidence for this period and the brevity of their reigns. Another of these poorly known rulers must be the mysterious Tutkheperre Shoshenq who was an early Dynasty 22 ruler since he is now monumentally attested in both Lower and Upper Egypt at Bubastis and Abydos respectively.

Evidence that Shoshenq II was a predecessor of Osorkon II is indicated by the fact that his hawk-headed coffin is stylistically similar to "a hawk-headed lid" which enclosed the granite coffin of king Harsiese A, from Medinet Habu.Harsiese A was an early contemporary of Osorkon II and likely Takelot I too since the latter did not control Upper Egypt in his reign. This implies that Shoshenq II and Harsiese A were near contemporaries since Harsiese A was the son of the High Priest of Amun Shoshenq C at Thebes and, thus, the grandson of Osorkon I.

Harsiese's funerary evidence places Shoshenq II roughly one or two generations after Osorkon I and may date him to the brief interval between Takelot I and Osorkon I at Tanis. In this case, the objects naming Shoshenq I in this king's tomb would simply be heirlooms, rather than proof of an actual filial relation between Shoshenq I and II.

This latter interpretation is endorsed by Jurgen von Beckerath, in his 1997 book, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Agypten who believes Shoshenq II was actually an elder brother of Takelot I. The view that Shoshenq II was an elder brother of Takelot I is also endorsed by Norbert Dautzenberg in a GM 144 paper. Von Beckerath, however, places Shoshenq II between the reigns of Takelot I and Osorkon II at Tanis.

Kenneth Kitchen, in his latest 1996 edition of '"The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (c.1100-650 BC)Õ", maintains that Shoshenq II was the High Priest of Amun Shoshenq C, son of Osorkon I and Queen Maatkare, who was appointed as the junior coregent to the throne but predeceased his father.

Kitchen suggests such a coregency is reflected on the bandages of the Ramesseum mummy of Nakhtefmut, which contain the dates "Year 3" and "Year 33 Second Heb Sed" respectively. The "Year 33" date mentioned here almost certainly refers to Osorkon I since Nakhtefmut wore a ring which bore this king's prenomen. Kitchen infers from this evidence that Year 33 of Osorkon I is equivalent to Year 3 of Shoshenq II, and that the latter was Shoshenq C himself.

Unfortunately, however, the case for a coregency between Osorkon I and Shoshenq II is uncertain because there is no clear evidence that the Year 3 and Year 33 bandages on Naktefmut's body were made at the same time. These two dates were not written on a single piece of mummy linen - which would denote a true coregency.

Rather, the dates were written on two separate and unconnected mummy bandages which were likely woven and used over a period of several years, as the burial practices of the Amun priests show. A prime example is the Mummy of Khonsmaakheru in Hamburg which contains separate bandages dating to Years 11, 12, and 23 of Osorkon I - or a minimum period of 12 Years between their creation and final use.

A second example is the mummy of Djedptahiufankh, the Third or Fourth Prophet of Amun, which bears various bandages from Years 5, 10, and 11 of Shoshenq I, or a spread of six years in their final use for embalming purposes. As these two near contemporary examples show, the temple priests simply reused whatever old or recycled linens which they could gain access to for their mummification rituals.

The Year 3 mummy linen would, hence, belong to the reign of Osorkon's successor. Secondly, none of the High Priest Shoshenq C's own children - the priest Osorkon whose funerary papyrus, P. Denon C, is located in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg or a second priest named Harsiese (likely king Harsiese A) who dedicated a Bes statue in memory of his father, now in Durham Museum - give royal titles to their father on their own funerary objects. The priest Osorkon only calls himself the "son of the High Priest Shoshenq", rather than the title "King's Son" in his funerary papyri, which would presumably have been created long after his father's death.

On Harsiese, Jacquet-Gordon notes that "there is no good evidence to suggest that the 1st prophet Shoshenq C ever claimed or was accorded royal rank." She observes that Harsiese designated his father as a High Priest of Amun on a Bes statue without any accompanying royal name or prenomen and stresses that if Shoshenq C "had even the slightest pretensions to royal rank, his son would not have omitted to mention this fact. We must therefore conclude that he had no such pretensions."

This implies that the High Priest Shoshenq C was not king Shoshenq II. While Shoshenq C's name is indeed written in a cartouche on the Bes statue, no actual royal name or prenomen is ever given. An example of a king's son who enclosed his name in a cartouche on a monument but never inherited the throne was Wadjmose, a son of the New Kingdom king Thutmose I.

More significantly, Shoshenq II's intact burial did not contain a single object or heirloom naming Osorkon I - an unlikely situation if Osorkon did indeed bury his own son. Kitchen notes that this king's burial goods included a pectoral that was originally inscribed for the Great Chief of the Ma Shoshenq I - before the latter became king - and "a pair of bracelets of Shoshenq I as king but no later objects."

This situation appears improbable if Shoshenq II was indeed Shoshenq C, Osorkon I's son who died and was buried by his own father. Other Dynasty 21 and 22 kings such as Amenemopet and Takelot I, for instance, employed grave goods which mentioned their parent's names in their own tombs.

Since this pharaoh's funerary objects such as his silver coffin, jewel pectorals, and cartonnage all give him the unique royal name Heqakheperre, he was most likely a genuine king of the 22nd Dynasty in his own right, and not just a minor coregent. Jurgen von Beckerath adopts this interpretation of the evidence and assigns Shoshenq II an independent reign of 2 years at Tanis.

In the most recent 2005 academic publication on Egyptian chronology, the Egyptologists Rolf Krauss and David Alan Warburton also ascribed Shoshenq II an independent reign of between 1 to 2 years in the 22nd dynasty although they place Shoshenq II's brief reign between that of Takelot I and Osorkon II. The exclusive use of silver for the creation of Shoshenq II's coffin is a potent symbol of his power because silver "was considerably rarer in Egypt than gold."

Dr. Derry's medical examination of Shoshenq II's mummy reveals that the king died as a result of a massive septic infection from a head wound. The final resting place of Shoshenq II was certainly a reburial because he was found interred in the tomb of another king, Psusennes I of the 21st Dynasty. Scientists have found evidence of plant growth on the base of Sheshonq II's coffin which suggests that Shoshenq II's original tomb had become waterlogged; hence, the urgent need to rebury him and his funerary equipment in Psusennes' tomb instead.

Hedjkheperre Setepenre Takelot I was a son of Osorkon I and Queen Tashedkhons who ruled Egypt for 13 Years according to Manetho. Takelot would marry Queen Kapes who bore him Osorkon II. Initially, Takelot was believed to be an ephemeral Dynasty 22 Pharaoh since no monuments at Tanis or Lower Egypt could be conclusively linked to his reign, or mentioned his existence, except for the famous Pasenhor Serapeum stela which dates to Year 37 of Shoshenq V.

However, since the late 1980s, Egyptologists have assigned several documents mentioning a king Takelot in Lower Egypt to him rather than Takelot II. Takelot I's reign was relatively short when compared to the three decades-long reigns of his father Osorkon I and son, Osorkon II. Takelot I, rather than Takelot II, was the king Hedjkheperre Setepenre Takelot who is attested by a Year 9 stela from Bubastis as well as the owner of a partly robbed Royal Tomb at Tanis which belonged to this ruler as the German Egyptologist Karl Jansen-Winkeln reported in a 1987 Varia Aegyptiaca 3 (1987), pp. 253-258 paper.

Evidently, both king Takelots used the same prenomen or royal name: Hedjkheperre Setepenre. The main difference between Takelot I and II is that Takelot I never employed the Theban inspired epithet 'Si-Ese' (Son of Isis) in his titulary, unlike Takelot II.

Takelot I's authority was not fully recognised in Upper Egypt, and Harsiese A, or another local Theban king, challenged his power there. Several Nile Quay Texts at Thebes mention two sons of Osorkon I namely the High Priests of Amun Iuwelot and Smendes III in Years 5, 8 and 14 of an anonymous king who can only be Takelot I since Takelot I was their brother.

Uniquely, however, the Quay Texts specifically omit any reference to the identity of the king himself. This might suggest that there was a dispute in the royal succession following Osorkon I's death in Upper Egypt, which seriously impaired Takelot I's control there. Harsiese A, as the son of the High Priest Shoshenq C and grandson of Osorkon I, or a hypothethical king named Maatkheperre Shoshenq must have appeared as a rival.

The Theban priests henceforth, chose to avoid any involvement in this dispute by deliberately leaving the name of the king in the Quay Texts 'Blank' rather than choosing sides, as G. Broekman notes in his study of the Karnak Quay Texts. This situation was ultimately later resolved by Osorkon II who is clearly attested as Pharaoh at Thebes by his 12th Regnal Year, according to Nile Quay Text No.8 and Text No.9.

Usermaatre Setepenamun Osorkon II was a pharaoh of the Twenty-second Dynasty of Ancient Egypt and the son of Takelot I and Queen Kapes. He ruled Egypt around 872 BC to 837 BC from Tanis, the capital of this Dynasty. After succeeding his father, he was faced with the competing rule of his cousin, king Harsiese A, who controlled both Thebes and the Western Oasis of Egypt.

Osorkon feared the serious challenge posed by Harsiese's kingship to his authority but, when Harsiese conveniently died in 860 BC, Osorkon II ensured that this problem would not recur by appointing his own son Nimlot C as the next High Priest of Amun at Thebes. This consolidated the pharaoh's authority over Upper Egypt and meant that Osorkon II ruled over a united Egypt. Osorkon II's reign would be a time of large scale monumental building and prosperity for Egypt

According to a recent paper by Karl Jansen-Winkeln, king Harsiese A, and his son were only ordinary Priests of Amun, rather than High Priests of Amun, as was previously assumed. The inscription on the Koptos lid for [..du], Harsiese A's son, never once gives him the title of High Priest. This demonstrates that the High Priest Harsiese who served is attested in statue CGC 42225 - which mentions this High Priest and is dated explicitly under Osorkon II - was, in fact, Harsiese B.

The High Priest Harsiese B served Osorkon II in his final 3 years. This statue was dedicated by the Letter Writer to Pharaoh Hor IX, who was one of the most powerful men in his time. However, Hor IX almost certainly lived during the end of Osorkon II's reign since he features on Temple J in Karnak which was built late in this Pharaoh's reign, along with the serving High Priest Takelot F(the son of the High Priest Nimlot C and therefore, Osorkon II's grandson). Hor IX later served under both Shoshenq III, Pedubast I and Shoshenq VI. This means that the High Priest Harsiese mentioned on statue CGC 42225 must be the second Harsiese: Harsiese B.

Despite his astuteness in dealings with matters at home, Osorkon II was forced to be more aggressive on the international scene. The growing power of Assyria meant the latter's increased meddling in the affairs of Israel and Syria - territories well within Egypt's sphere of influence. In 853 BC, Osorkon's forces, in a coalition with those of Israel and Byblos, fought the army of Shalmaneser III at the Battle of Qarqar to a standstill thereby halting Assyrian expansion in Canaan, for a brief while.

Osorkon II devoted considerable resources into his building projects by adding to the temple of Bastet at Bubastis which featured a substantial new hall decorated with scenes depicting his Sed festival and images of his Queen Karomama. Mutemhat was another of his wives. Monumental construction was also performed at Thebes, Memphis, Tanis and Leontopolis. Osorkon II also built Temple J at Karnak during the final years of his reign, which was decorated by his then serving High Priest Takelot F(the future Takelot II).

Takelot F was the son of the deceased High Priest Nimlot C and, thus, Osorkon II's grandson. Osorkon II was the last great Twenty-second Dynasty king of Tanis who ruled Egypt from the Delta to Upper Egypt because his successor, Shoshenq III lost effectively control of Middle and Upper Egypt in his 8th Year with the emergence of king Pedubast I at Thebes.

Many officials are datable under Osorkon II. Ankhkherednefer was inspector of the palace; Djeddjehutyiuefankh was fourth prophet of Amun; Bakenkhons was another prophet of Amun under that king.

Osorkon II is known to have had at least three wives.

Other possible children attributed to Osorkon II include his successor Sheshonk III and the King's Daughter Tentsepeh (D), the wife of General Ptahudjankhef, who was himself a son of Nimlot C, and hence a grandson of Osorkon II.

David Aston has convincingly argued in a JEA 75 (1989) paper that Osorkon II was succeeded by Shoshenq III at Tanis rather than Takelot II Si-Ese as Kitchen assumed because none of Takelot II's monuments have been found in Lower Egypt where other genuine Tanite kings such as Osorkon II, Shoshenq III and even the short-lived Pami (at 6-7 Years) are attested on donation stelas, temple walls and/or annal documents.

Other Egyptologists such as Gerard Broekman, Karl Jansen-Winkeln, Aidan Dodson and Jurgen von Beckerath have also endorsed this position. von Beckerath also identifies Shoshenq III as the immediate successor of Osorkon II and places Takelot II as a separate king in Upper Egypt.

Gerard Broekman writes in a recent 2005 GM article that "in light of the monumental and genealogical evidence," Aston's Chronology for the position of the 22nd Dynasty kings "is highly preferable" to Kitchen's chronology. The only documents which mention a king Takelot in Lower Egypt such as a royal tomb at Tanis, a Year 9 donation stela from Bubastis and a heart scarab featuring the nomen 'Takelot Meryamun' - have now been attributed exclusively to king Takelot I by Egyptologists today including Kitchen himself.

The English Egyptologist Aidan Dodson in his book, The Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt, observes that Shoshenq III built "a dividing wall, with a double scene showing Osorkon II" and himself "each adoring an unnamed deity" in the antechamber of Osorkon II's tomb.

Dodson concludes that while one may argue Shoshenq III erected the wall to hide Osorkon II's sarcophagus, it made no sense for Shoshenq to create such an elaborate relief if Takelot II had really intervened between him and Osorkon II at Tanis for 25 years unless Shoshenq III was Osorkon II's immediate successor. Shoshenq III must, hence, have wished to associate himself with his predecessor - Osorkon II. Consequently, the case for establishing Takelot II as a Twenty-second Dynasty king and successor to Osorkon II disappears, as Dodson writes.

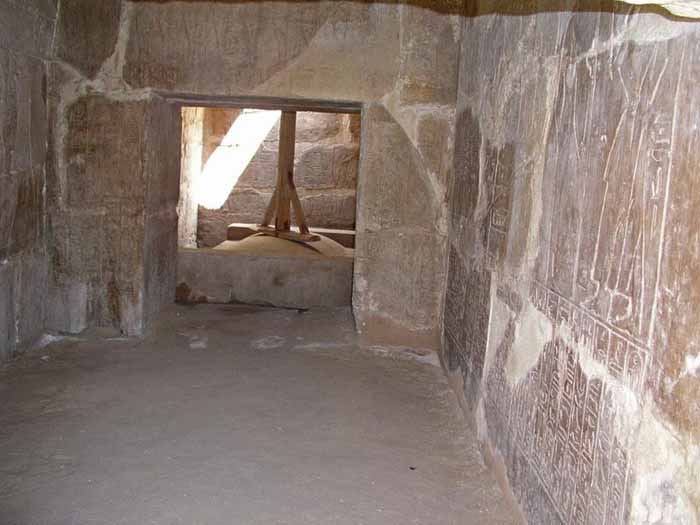

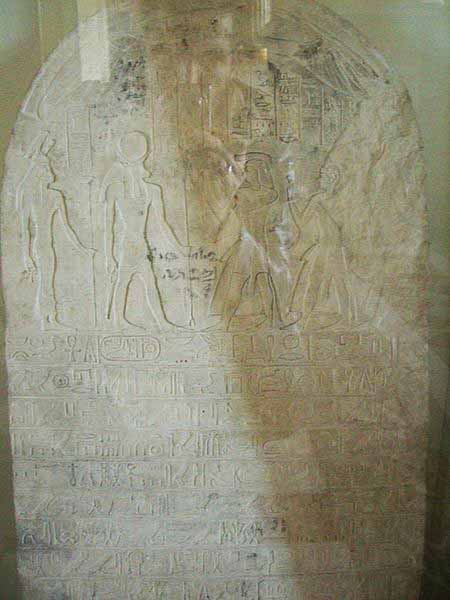

Interior photo of the tomb of Osorkon II

Reliefs from the Tomb of Osorkon II

The French excavator, Pierre Montet discovered Osorkon II's plundered royal tomb at Tanis on February 27, 1939. It revealed that Osorkon II was buried in a massive granite sarcophagus with a lid carved from a Ramesside era statue. Only some fragments of a Hawk-headed coffin and canopic jars remained in the robbed tomb to identify him. While the tomb had been looted in antiquity, what jewelery which remained "was of such high quality that existing conceptions of the wealth of the northern Twenty-first and Twenty-second dynasties had to be revised."

Osorkon II died around 837 BC and is buried in Tomb NRT I at Tanis. He is now believed to have reigned for more than 30 years, rather than just 25 years. The celebrations of his first Sed Jubilee was traditionally thought to have occurred in his 22nd Year but the Heb Sed date in his Great Temple of Bubastis is damaged and can be also be read as Year 30, as Edward Wente notes. The fact that this king's own grandson, Takelot F, served him as High Priest of Amun at Thebes-as the inscribed Walls of Temple J prove - supports the hypothesis of a longer reign for Osorkon II.

King Usermaatre Setepenre or Usimare Setepenamun Shoshenq III ruled Egypt's 22nd Dynasty for 39 years according to contemporary historical records. Two Apis Bulls were buried in the fourth and 28th years of his reign and he celebrated his Heb Sed Jubilee in his regnal year 30. Little is known of the precise basis for his successful claim to the throne since he was not a son of Osorkon II and Shoshenq's parentage and family ties are unknown.

From Shoshenq III's eighth regnal year, his reign was marked by the loss of Egypt's political unity, with the appearance of Pedubast I at Thebes. Henceforth, the kings of the 22nd Dynasty only controlled Lower Egypt.

The Theban High Priest Osorkon B (the future Osorkon III) did date his activities at Thebes and (Upper Egypt) to Shoshenq III's reign but this was solely for administrative reasons since Osorkon did not declare himself king after the death of his father, Takelot II. On the basis of Osorkon B's well known Chronicle, most Egyptologists today accept that Takelot II's 25th regnal year is equivalent to Shoshenq III's 22nd year.

Shoshenq III married Djed-Bast-Es-Ankh, the daughter of Takelot, a High Priest of Ptah at Memphis, and Tjesbastperu, Osorkon II's daughter. He had at least 4 sons and 1 daughter: Ankhesen-Shoshenq, Bakennefi A, Pashedbast B, Pimay the 'Great Chief of the Ma', and Takelot C, a Generalissimo.

A certain Padehebenbast may also have been another son of Shoshenq III but this is not certain. They all appear to have predeceased their father through his nearly four decade long rule. Shoshenq III's third son, Pimay ('The Lion' in Egyptian), was once thought to be identical with king Pami ('The Cat' in Egyptian), but it is now believed that they are two different individuals, due to the separate orthography and meaning of their names. Instead, it was an unrelated individual named Shoshenq IV who ultimately succeeded Shoshenq III.

Hedjkheperre Setepenre Shoshenq IV ruled Egypt's 22nd Dynasty between the reigns of Shoshenq III and Pami. This Pharaoh's existence was first argued by David Rohl[citation needed] but the British Egyptologist Aidan Dodson settled the issue in a seminal GM 137(1993) article.

Dodson's arguments here for the existence of a new Tanite king called Shoshenq IV is accepted by all Egyptologists today including J. Von Beckerath and Kenneth Kitchen the latter in the preface to the third edition of his book on the Third Intermediate Period in Egypt."

While Shoshenq IV shared the same prenomen as his illustrious ancestor Shoshenq I, he is distinguished from Shoshenq I by his use of an especially long nomen-Shoshenq Meryamun Si-Bast Netjerheqawaset/Netjerheqaon which featured both the Si-Bast and Netjerheqawaset/Netjerheqaon epithets.

These two epithets were gradually employed by the 22nd Dynasty Pharaohs starting from the reign of Osorkon II. In contrast, Shoshenq I's nomen reads simply as "Shoshenq Meryamun" while neither Shoshenq I, Osorkon I nor Takelot I ever used any epithets beyond the standard 'Meryamun' (Beloved of Amun) form during their reigns.

Aidan Dodson - in his 1994 book on the Canopic Equipment of the kings of Egypt - perceptively observes that when the Si-Bast epithet "appears during the dynasty of Osorkon II," it is rather infrequent while the Netjerheqawaset/Netjerheqaon epithet is only exclusively attested "in the reigns of that monarch's successors"- ie. Shoshenq III, Shoshenq IV, Pami and Shoshenq V.

This means that Shoshenq IV was a late Tanite era king who ruled Egypt after Shoshenq III. His prenomen is explicitly attested on a published Year 10 stela (St. Petersburg Hermitage 5630) which bears his unique long form titulary. This stela mentions the Chief of the Libu, Niumateped, who is also attested in office in Year 8 of Shoshenq V. Since the title 'Chief of the Libu' is only first documented in use from Year 31 of Shoshenq III onwards, this new king again can only have ruled after Shoshenq III.

In the tomb's debris, several fragments were found from one or two canopic jars bearing the name "Hedjkheperre-Setpenre-meryamun-sibast-Netjerheqaon." Since the epithet Netjerheqaon was never employed by the 22nd Dynasty kings until the reign of Shoshenq III, this is clear evidence that Shoshenq IV was buried in Shoshenq III's Tanite tomb and must have succeeded this king; it also establishes that the king buried here was certainly not Shoshenq I.

The original king Shoshenq IV in pre-1993 books and journal articles has been renamed Shoshenq VI by Egyptologists because he was a Theban king who is only attested by Upper Egyptian documents. He was never a king of the Tanite 22nd Dynasty of Egypt.

Usermaatre Setepenre Pami was an Egyptian Pharaoh who ruled Egypt for 7 years. He was a member of the Twenty-second dynasty of Egypt of Meshwesh Libyans who had been living in the country since the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt when their ancestors infiltrated into the Egyptian Delta from Libya. Their descendants began to rule Egypt from the mid-940s BC onwards with the ascendance of Shoshenq I to power. Pami's name, in Egyptian, means the Cat or "He who belongs to the Cat [Bastet].

Pami's precise relationship with his immediate predecessor - Hedjkheperre Setepenre Shoshenq IV - is unknown but he is attested as the father of Shoshenq V in a Year 11 Serapeum stela dating to the latter's reign. Pami was once assumed to be Pimay, the third son of Shoshenq III who served as the "Great Chief of Ma" under his father.

However, the different orthographies of their names (Pami vs. Pimay) prove that they were 2 different individuals. In addition, the name Pami translates as 'The Cat' in Egyptian whereas the name Pimay means 'The Lion.' Pami's name was mistakenly transcribed as Pimay by past historians based upon the common belief that he was Shoshenq III's son.

This is now recognized to be an erroneous translation of this king's nomen/name which should rather be written as Pami. While a previous Dynasty 22 king held the title 'Great Chief of the Ma' before ascending the throne-namely Shoshenq I-Shoshenq III's son, Pimay, was a different man from king Pami because their names are different.

Moreover, if Pimay did indeed outlive his father, he should have then succeeded his father as king rather than the obscure Shoshenq IV who is not attested as a son of Shoshenq III. Consequently, it seems certain that Shoshenq III outlived all of his sons through his nearly 4 decade long reign.

While a minority of scholars hold to the traditional view that Pami was Pimay, a son of Shoshenq III by his wife Queen Djed-Bast-Es-Ankh, no archaeological evidence proves that Pami was ever a son of Shoshenq III. The different spelling and meanings of the word Pami and Pimay and the fact that Shoshenq III was actually succeeded by Shoshenq IV - rather than Pimay as was once thought - suggest rather that Pami was a son of his obscure predecessor - Shoshenq IV instead.

Two Apis bulls were buried in Pami's own reign - one each during his Second and Sixth Year respectively. The Year 2 II Peret day 1 Serapeum stela from Pami's reign states that 26 Years passed between Year 28 of Shoshenq III-the burial of the previous Apis Bull - and Year 2 of Pami.

Pami's Highest Year Date was originally thought to be his 6th Year based on his Year 6 Serapeum stela. However, in 1998, Pierre Tallet, Susanne Bickel and Marc Gabolde from the University of Montpellier published the surviving contents of a reused stone block from an enclosure wall at Heliopolis in a BIFAO 98(1998) paper titled "Heliopolitan Annals from the Third Intermediate Period."

According to the article, the block is 2 cubits (104 cm) large and likely formed the right inside side of a doorway. The block is essentially an Annal document which postdates Pami's reign and was originally part of a larger monument which catalogued the deeds of various Dynasty 22 Pharaohs. However, only the section concerning Pami's reign has survived.

It chronicles this king's Yearly donations both to the gods of the Great Temple of Heliopolis and to other local deities and temples in this city. While the ending of the block is damaged, a 7th Regnal Year can be clearly seen for Pami and a brief 8th Year in the lost or erased section is possible. In any event, his Highest Year Date is now his 7th Year and Pami would have reigned for almost 7 full years based upon this document.

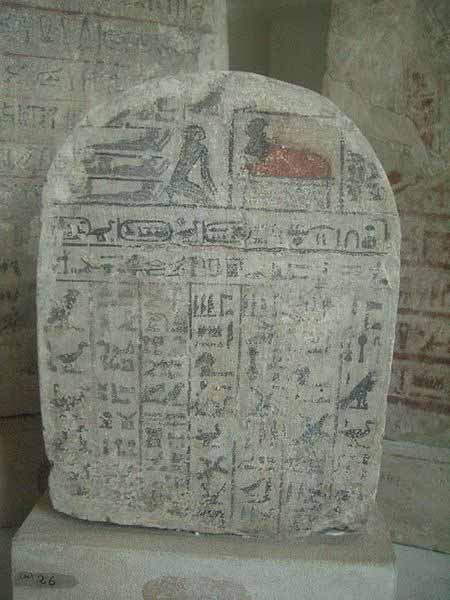

Year 11 Apis stela of Shoshenq V (Louvre Museum)

Shoshenq V was the final king of the Twenty-second dynasty of Egypt of Meshwesh Libyans which controlled Lower Egypt. He was the son of Pami according to a Year 11 Serapeum stela from his reign. His prenomen or throne name, Akheperre, means "Great is the Soul of Re."

The burial of two Apis Bulls is recorded in Year 11 and Year 37 of his reign. Shoshenq V's highest Year date is an anonymous Year 38 donation stela from Buto created by the Libyan Chief Tefnakht of Sais which can only belong to his reign since Tefnakht was a late contemporary of this king. This stela, which reads simply as "Regnal Year 38 under the Majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, BLANK, Son of Re, BLANK," may reflect the growing power of Tefnakht in the Western Delta at the expense of Shoshenq V whose name is omitted from the document.

Shoshenq V is believed to have died around 740 BC after a reign lasting 38 years. With his death, the Libyan 22nd Dynasty kingdom in the Egyptian Delta disintegrated into various city states under the control of numerous local kinglets such as Tefnakht at Sais and Buto, Osorkon IV at Bubastis and Tanis, and Iuput II at Leontopolis. [edit]

Pedubast II was a Pharaoh of Egypt associated with the 22nd Dynasty. Not mentioned in all King lists, he is mentioned as a possible son and successor to Shoshenq V by Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton in their 2004 book, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. They give his reign as about 743-733 BC, between Shoshenq V and Osorkon IV.

Osorkon IV was a ruler of Lower Egypt who, while not always listed as a member of the Twenty-second dynasty of Egypt, he is attested as the ruler of Tanis - and thereby one of Shoshenq V's successors. Therefore he is sometimes listed as part of the dynasty, whether for convenience or in fact. His parentage is uncertain: he could be a son of Shoshenq V. His mother, named on an electrum headpiece in the Louvre, is Tadibast III.

Kenneth Kitchendoes notBold text give his reign dates as 732/30 - 716 BC. His reign was never recognized at Memphis where documents were dated to the reign of 24th Saite dynasty king Bakenranef. During his time, Egypt was ruled concurrently by four dynasties - 22nd, 23rd, 24th and the 25th. Shortly after Osorkon had ascended the throne, Upper Egypt was conquered by the Kushite king, Piankhi, and Osorkon IV ended ruling only the East Nile Delta region.

Relationship with Assyria

He is perhaps mentioned in the bible as the Pharaoh "So" to whom Hoshea, King of Israel appealed for help. However, So dispatched no aid or troops. The Israelite capital Samaria was captured by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser V in 722 BC and its inhabitants were imprisoned and taken to exile in Assyria and Media. To avoid military conflict with the Assyrians or even invasion, Osorkon sent presents, including several horses, to placate the new Assyrian king Sargon II, who rose to power later in 722. Osorkon's tactic apparently worked, since Sargon accepted his gifts and did not take action against him.