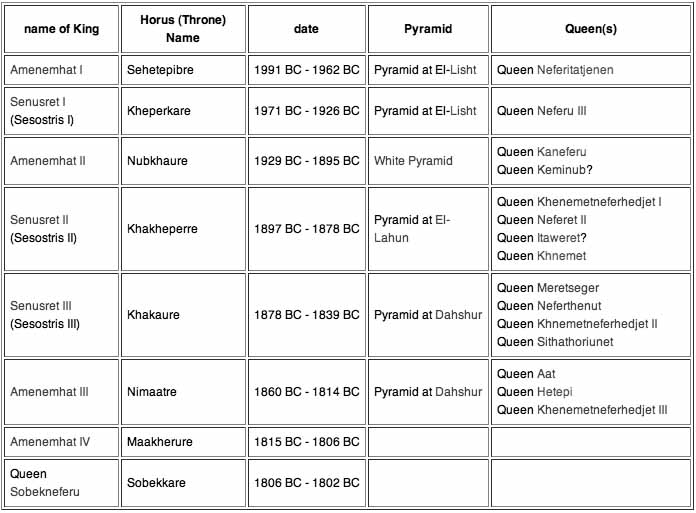

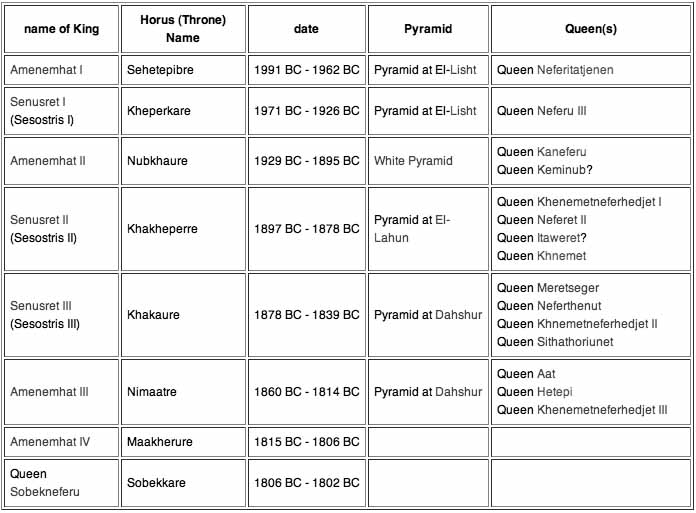

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty XII) is often combined with Dynasties XI, XIII and XIV under the group title Middle Kingdom.

The chronology of the 12th dynasty is the most stable of any period before the New Kingdom. The Ramses Papyrus Canon in Turin gives 213 years (1991-1778 BC. Manetho stated that it was based in Thebes, but from contemporary records it is clear that the first king moved its capital to a new city named "Amenemhat-itj-tawy" ("Amenemhat the Seizer of the Two Lands"), more simply called Itjtawy. The location of Itjtaway has not been found, but is thought to be near the Fayyum, probably near the royal graveyards at el-Lisht. Egyptologists consider this dynasty to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom.

The order of its rulers is well known from several sources - two lists recorded at temples in Abydos and one at Saqqara, as well as Manetho's work. A recorded date during the reign of Senusret III can be correlated to the Sothic cycle, consequently many events during this dynasty are frequently assigned to a year BC or BCE.

According to Manetho, the 12th Dynasty comprised seven kings from Thebes, who ruled for a total of 160 years in the version of Africanus, and for 245 years in the version of Eusebius. Oddly enough, this does not include

the founder of the dynasty, Amenemhat I, who is added in succession to the kings of the 11th Dynasty.

In the Turin King-list, the dynasty started with Amenemhat I and consisted of 8 kings who ruled for a total of 213 years, 1 month and 17 days. All kings listed in the Turin King-list are also attested by contemporary sources and monuments.

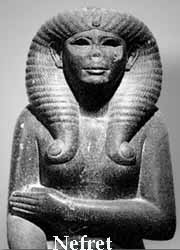

The circumstances into which the 12th Dynasty came to power are not known. What is known is that Amenemhat I was not related to his predecessors. His father was a priest in Thebes named Senuseret. His mother was named Nefret and, according to the Prophecy of Neferti, came from Elephantine in the South of Egypt.

It is possible that Amenemhat was the vizier of Mentuhotep IV, the last king of the 11th Dynasty. A stone plate found at Lisht, bearing both the names of Mentuhotep IV and of king Amenemhat I may perhaps indicate that Amenemhat I was a co-regent during the later years of Mentuhotep's reign. This could perhaps indicate that Mentuhotep IV had intended Amenemhat to be his successor.

With the 12th Dynasty, a local god of obscure origin, Amun, would become the most important god of the Ancient Egyptian pantheon. The popularity of Amun is closely linked to the origin of Amenemhat I, whose name, containing the element Amun, shows a particular allegiance to this god. Even when Amenemhat moved the political center of the country from Thebes to the newly built capital Itj-tawi in the Fayum oasis, located to the southwest of the old capital Memphis, Thebes would remain an important religious center. This would determine the religious and political history of Ancient Egypt for the following millennium.

The kings of the 12th Dynasty ruled the country firmly and were able to maintain the power of balance between the central authorities and the local administrations, to their own advantage. They also imposed their rule on northern Nubia and pacified the Bedouins in the deserts to the east and west of the Nile Valley. Imposing fortresses were built in Nubia and at the Eastern border, to protect trading routes from raiding Bedouins.

The wealth and stability the 12th Dynasty has brought to the country is evidenced in the high quality of statues, reliefs and paintings found throughout the country. Rather typical for this period are statues with big ears, seen by some as an indication that the king and his nobility listened to their subjects.

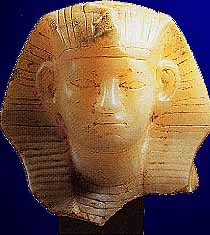

Deviating from the standard way of representing kings, Sesostris III and his successor Amenemhat III (see image to the left) had themselves portrayed as mature, aging men. This is often interpreted as a portrayal of the burden of power and kingship. That the change in representation was indeed ideological and should not be interpreted as the portrayal of an aging king is shown by the fact that in one single relief, Sesostris III was represented as a vigorous young man, following the centuries old tradition, and as a mature aging king.

The brilliant Egyptian twelfth dynasty came to an end in the 18th century BC with the death of Queen Sobekneferu (1777 BC - 1773 BC). Apparently, she had no heirs, causing the twelfth dynasty to come to a sudden end as did the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom, which was succeeded by the much weaker thirteenth dynasty of Egypt. Retaining the seat of the twelfth dynasty, the thirteenth dynasty ruled from Itjtawy ("Seizer-of-the-Two-Lands") near Memphis and el-Lisht, just south of the apex of the Nile Delta.

Amenemhat I was the first ruler of the 12th Dynasty.

Amenemhat I, also Amenemhet I, was the first ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty (the dynasty considered to be the beginning of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt). He ruled from 1991 BC to 1962 BC. Amenemhat I was a vizier of his predecessor Mentuhotep IV, overthrowing him from power, scholars vary if Mentuhotep IV was killed by Amenemhat I, but there is no independent evidence to support this and there may even have been a period of co-regency between their reigns.

Amenemhet I was not of royal lineage, and the composition of some literary works (the Prophecy of Neferti, the Instructions of Amenemhat) and, in architecture, the reversion to the pyramid-style complexes of the 6th dynasty rulers are often considered to have been attempts at legitimizing his rule. Amenemhat I moved the capital from Thebes to Itjtawy and was buried in el-Lisht.

His son Senusret I followed in his footsteps, building his pyramid - a closer reflection of the 6th dynasty pyramids than that of Amenemhat I - at Lisht as well, but his grandson, Amenemhat II, broke with this tradition.

Some Egyptologists believe that recovery from the First Intermediate Period into the Middle Kingdom only really began with his rule. He was probably not of royal blood, at least if he is the same Vizier that functioned under his predecessor, Mentuhotep IV. Perhaps either Mentuhotep IV had no heir, or he was simply a weak leader. This vizier, named Amenemhet, recorded an inscription when Mentuhotep IV sent him to Wadi Hammamt. The inscription records two omens. The first tells us of a gazelle that gave birth to her calf atop the stone that had been chosen for the lid of the King's sarcophagus. The second was of a ferocious rainstorm that, when subsided, disclosed a well 10 cubits square and full of water. Of course that was a very good omen in this barren landscape.

Many Egyptologists believe that Amenemhet's inscription implies that a great ruler will come to the throne of Egypt upon the death of Mentuhotep IV, who will lead the country into prosperity.

It is fairly certain that Amenemhet the vizier was predicting his own rise to the throne as Amenemhet I. However, we are told that he had at least two other competitors to the throne. One was called Inyotef, and the other a Segerseni from Nubia. It would appear that he quickly dealt with these obstacles. We believe that he ruled Egypt for almost 30 years. Peter A. Clayton places his reign between the years of 1991 and 1962 BC while the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt gives him a reign lasting from 1985 through 1956 BC. Dodson has his reign lasting from 1994 until 1964 BC.

Amenemhet I's Horus name, Wehem-mesut, means "he who repeats births", and almost certainly was chosen to commemorate the new dynasty and a return to the values and prosperity of a united Egypt. Amenemhet (Amenemhat) was his birth name and means "Amun is at the Head". He was called Ammenemes I by the Greeks. His throne name was Sehetep-ib-re, which means "Satisfied is the Heart of Re".

Neferu, who was the principal wife of Senwosret I, the kings mother, Nefret, and a principal wife, Nefrytatenen

Amenemhet was probably the son of a woman named Nofret (Nefret), from Elephantine near modern Aswan, and a priest called Senusret, according to an inscription at Thebes. So his origins are probably southern Egypt. We know of three possible wives including Neferytotenen (Nefrutoteen, Nefrytatenen), who may have been the mother of Amenemhet I's successor, Senusret I, Dedyet, who was may also have been his sister, and Sobek'neferu, Neferu).

IIt is fairly clear that Amenemhet established Egypt's first co-regency with his son, Senusret I, in about the older kings 20th year of rule. He was not only seeking to assure the succession of his proper heir, but also providing the young prince valuable training under his tutelage. Senusret was given several active roles in Amenemhet I's government, specifically including matters related to the military matters. Several pieces of literature that probably date from his reign, some of which appears to support his reign with fables of kingship. One, the Discourse of Neferty, has a ruler emerging named Ameny, who was foretold by a prophet in the Old Kingdom (Neferty).

Neferti was a Heliopolis sage who seems familiar to us from Djedi in the Papyrus Westcar. He is summoned to the court of Snofru, during who's reign the story is suppose to have taken place. This tale has Ameny delivering Egypt from chaos, but it should be noted that it is the chaos of the late 11th Dynasty, not the First Intermediate Period.

Then a king will come from the South, Ameny, the justified, my name, Son of a woman of Ta-Seti, child of Upper Egypt, He will take the white crown, he willjoin the Two Mighty Ones (the two crowns)

We do not know what year this literature dates to within Amenemhet I's reign. But while there are other text that refer to the chaos before the arrival of new kings, the references to Asiatics and the Walls-of-the-Ruler are new.

Amenemhet I set about consolidating the country in a very purposeful manner. He moved his capital north to the capital he apparently established named Amenemhet-itj-tawy, which means, "Amenemhet the Seizer of the Two lands". It was located south of Memphis, on the edge of the Fayoum Oasis, though the city ruins have not yet been discovered. This gave him a more central control of Egypt, as well as placing him nearer to problem areas in the Delta. It also signaled the end of an old era and new beginnings. This move was perhaps only carried out a short time after he took the throne.

Many Egyptologists believe that the move was made at the very beginning of his reign, while a few believe it may have been much later, around the time of his twentieth year as ruler. However, he did begin a tomb at Thebes, and then abandoned it for a pyramid at el-Lisht, near the new capital. It appears that the work on the tomb at Thebes may have taken between three and five years to complete. Also, there are very few of his monuments located near Thebes, suggesting that he soon moved away.

His pyramid at el Lisht is instructional, for it seems to portray a return to some of the values of the Old Kingdom, while still embracing the Theban concepts of the region of his birth. Egyptologists who believe Amenemhet I may have waited until his twentieth year to make the move to his new city base their evidence on an inscription found on the foundation blocks of the pyramid's mortuary temple. It records Amenemhet's royal jubilee, and also that year one of a new king had elapsed, suggesting that the pyramid was started very late in the king's reign. Therefore, considerable debate remains over the timing of his move.

He also reorganized the administration of the country, keeping the nomarchs who had supported him, while weakening the regional governors by appointing new officials at Asyut, Cusae and Elephantine. An inscription records that he also divided the nomes (provinces) into different sets of towns and redistributed the territories by reference to the Nile flood. We see a steady march during Amenemhet I's rule back to a more centralized government, together with an increase in bureaucracy. Another move, both to dilute the army's power and to raise personnel for coming conflicts, was his reintroduction of conscription.

Undoubtedly, in the Discourse of Neferty, Asiatics refer to the people who were causing trouble on the Egypt's eastern frontier. One of Amenemhet I's earliest campaigns were against these Asiatics, though the scale of these operations is unknown. He drove these people back, and indeed did build the Walls-of-the-Ruler, as series of fortifications along Egypt's northeastern frontier. However, even as late as his 24th year of rule, we still find inscriptions recording expeditions against these "and-dweller". None of these fortifications has ever been found, though the remains of a canal in the region may date from the period. Apparently, in the midst of the Asiatic campaign, he also found time to crush a few unrepentant local governors (nomarchs).

In Nubia, Amenemhet I first pushed his army southward to Elephantine, where he consolidated his rule and seems to have been satisfied for a number of years. This expedition was apparently lead by Khnemhotpe I, governor of the Oryx nome, who traveled up the Nile with 20 boats. But by year 29 of his rule, the king appears to have no longer been happy with the lose trading and quarrying network with Nubia that we find in the Old Kingdom.

The new policy was one of conquest and colonization with the principle aim of obtaining raw materials, especially gold. An inscription at the northern Nubian site of Korosko about half way between the first and second cataracts (rapids) states that the people of Wawat (northern Nubia) were defeated in his 29th year, and he apparently drove his army as far south as the second cataract.

In order to protect Egypt and fortify captured territory in Nubia, he founded a fortress at Semna and Quban in the region of the second Nile Cataract, which would begin a string of future 12th Dynasty fortresses. Along with protecting his newly acquired territory and the gold mines in Wadi Allaqi, he also created a stranglehold over economic contacts with Upper Nubia and further south. We also know that he constructed a fortress at Mendes named Rawaty.

From a foreign relations standpoint, we also know that diplomatic and commercial relations were renewed, after a long absence, with Byblos and the Aegean world.

Amenemhet I took part in a number of building projects. Besides his fortresses, we know he built at Babastis, el-Khatana and Tanis. He undertook important building works at Karnak, from which a few statues and granite naos survive. He may have even established the original temple of Mut to the south of the Temple of Amun.

He also worked at Koptos (Coptos), where he partly decorated the temple of Min, at Abydos, where he dedicated a granite altar to Osiris, at Dendera, where he built a granite gateway to Hathor and at Memphis, where he built a temple of Ptah. Also a little north of Tell el-Dab'a, he apparently began a small mudbrick temple at Ezbet Rushdi, that was later expanded by Senusret III.

Religiously, being from southern Egypt, Amenemhet I's allegiance was probably to the god Amun, and in fact, we find from this period forward the rise of Amun, at the expense of Montu, god of war, as the supreme deity of Thebes.

It is also notable that we find an increase in the mineral wealth of the royal family. We find a huge increase in the jewelry caches found in several 12th Dynasty royal burials. It is obvious from several sources of evidence that even the standard of living form middle class Egyptians was on the increase, though their level of wealth was proportional to their official offices.

Amenemhet I appears to have been a very wise leader, setting about to correct the problems of the First Intermediate Period, protecting Egypt's boarders from invasion and assuring a legitimate succession.

Yet he was murdered in an apparent harem plot while his co-regent was leading a campaign in Libya. Again, we find two literary works, the Tale of Sinuhe and the Instructions of Amenemhet I, reflecting this king's tragic end. One literary work from the time of Senusret I presents the account of Amenemhet I's murder, supposedly provided by the king himself from beyond the grave:

"It was after supper, when night had fallen, and I had spent an hour of happiness. I was asleep upon my bed, having become weary, and my heart had begun to follow sleep. When weapons of my counsel were wielded, I had become like a snake of the necropolis. As I came to, I awoke to fighting, and found that it was an attack of the bodyguard. If I had quickly taken weapons in my hand, I would have made the wretches retreat with a charge! But there is none mighty in the night, none who can fight alone; no success will come without a helper. Look, my injury happened while I was without you, when the entourage had not yet heard that I would hand over to you when I had not yet sat with you, that I might make counsels for you; for I did not plan it, I did not foresee it, and my heart had not taken thought of the negligence of servants."

Apparently, his foresight in creating the co-regency with his son proved successful, for Senusret I succeeded his father and their seems to have been little or no disruption in the administration of the country.

Amenemhat I was murdered. His body was buried in his pyramid at el-Lisht, near the Fayum oasis.

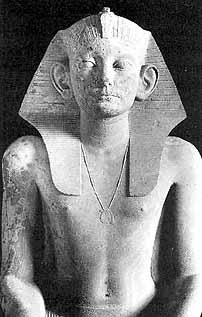

Senusret I (also Sesostris I and Senwosret I) was the second pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1971 BC to 1926 BC, and was one of the most powerful kings of this Dynasty. He was the son of Amenemhat I and his wife Nefertitanen. His wife and sister was Neferu. She was also the mother of the successor Amenemhat II. Senusret I was known by his prenomen, Kheperkare, which means "the Ka of Re is created."

He continued his father's aggressive expansionist policies against Nubia by initiating two expeditions into this region in his 10th and 18th Years and established Egypt's formal southern border near the second cataract where he placed a garrison and a victory stele. He also organized an expedition to a Western Desert oasis in the Libyan desert. Senusret I established diplomatic relations with some rulers of towns in Syria and Canaan. He also tried to centralize the country's political structure by supporting nomarchs who were loyal to him. His pyramid was constructed at el-Lisht. Senusret I is mentioned in the Story of Sinuhe where he is reported to have rushed back to the royal palace in Memphis from a military campaign in Asia after hearing about the assassination of his father, Amenemhat I.

Senusret I dispatched several quarrying expeditions to the Sinai and Wadi Hammamat and built numerous shrines and temples throughout Egypt and Nubia during his long reign. He rebuilt the important temple of Re-Atum in Heliopolis which was the centre of the sun cult. He erected 2 red granite obelisks there to celebrate his Year 30 Heb Sed Jubilee. One of the obelisks still remains and is the oldest standing obelisk in Egypt. It is now in the Al-Masalla (Obelisk in Arabic) area of Al-Matariyyah district near the Ain Shams district (Heliopolis). It is 67 feet tall and weighs 120 tons or 240,000 pounds.

Senusret I is attested to be the builder of a number of major temples in Ancient Egypt, including the temple of Min at Koptos, the Satet-Temple on Elephantine, the Month-temple at Armant and the Month-temple at El-Tod, where a long inscription of the king is preserved.

A shrine (known as the White Chapel) with fine, high quality reliefs of Senusret I, was built at Karnak to commemorate his Year 30 jubilee. It has subsequently been successfully reconstructed from various stone blocks discovered by Henri Chevrier in 1926. Finally, Senusret remodeled the Temple of Khenti-Amentiu Osiris at Abydos, among his other major building projects.

Some of the key members of the court of Senusret I are known. The vizier at the beginning of his reign was Intefiqer, who is known from many inscriptions and from his tomb next to the pyramid of Amenemhat I. He seems to have held this office for a long period of time and was followed by a vizier named Senusret. Two treasurers are known from the reign of the king: Sobekhotep (year 22) and Mentuhotep. The latter had a huge tomb next to the pyramid of the king and he seems to have been the main architect of the Amun temple at Karnak.

Senusret was crowned coregent with his father, Amenemhat I, in his father's 20th regnal year. Towards the end of his own life, he appointed his son Amenemhat II as his coregent. The stele of Wepwaweto is dated to the 44th year of Senusret and to the 2nd year of Amenemhet, thus he would have appointed him some time in his 43rd year. Senusret is thought to have died during his 46th year on the throne since the Turin Canon ascribes him a reign of 45 Years.

Senusret I embraces the creator god, Ptah at Karnak

Senusret I with Amun-Re at Karnak

In order to facilitate these building projects, he sent expeditions to exploit the stone quarries of Wadi Hammamat, the Sinai at Serabit el-Khadim, Hatnub, where two expeditions were sent in years 23 and 31 of his reign for alabaster, and Wadi el Hudi. One of these expeditions extracted enough stone to make sixty sphinxes and 150 statues. Many of his statues did not survive the ages, but the Egyptian Antiquity Museum includes a large collection of those that did.

Fragment from Karnak pillar with King and Horus

He also built a large pyramid, very reminiscent of older complexes, at Lisht, near Itjtawy, the capital apparently founded by his father. His pyramid is located just to the south of his father's pyramid at el-Lisht.

-

-

His throne name was 'Nub-kau-re'

'Golden are the Souls of Re'

Ammenemes II (Greek)

Amun is at the Head

Nubkhaure Amenemhat II was the third pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. Not much is known about his reign. He ruled Egypt for 35 years from 1929 BC to 1895 BC and was the son of Senusret I through the latter's chief wife, Queen Nefru His queen is not known; although recently a certain 'king's wife' named Senet has been proposed. His prenomen or throne name, Nubkaure, means "Golden are the Souls of Re."

The most important monument of his reign are the fragments of an annual stone found at Memphis, reused in the New Kingdom. It reports events of the first years of his reign. Donations to various temples are mentioned as well as a campaign to Southern Palestine and the destruction of two cities. The coming of Nubians to bring tribute is also reported. Amenemhat II established a coregency with his son Senusret II in his 33rd Regnal Year in order to secure the continuity of the royal succession.

His pyramid was constructed at Dahshur and is only little researched. Next to the pyramid were found the tombs of several royal women some of them were found undisturbed and still contained golden jewelery.

The court of the king is not well known. Senusret and Ameny were the viziers at the beginning of the reign. Two treasurers are known: Merykau and Zaaset. The overseer of the gateway Khentykhetywer is attested on a stela, where he reports an expedition to Punt.

Amenemhat II and his son, Senusret II, shared a brief coregency, which was the last certain one of the Middle Kingdom. The stela of Hapu at Aswan dates to the third year of Senusret II and to the 35th year of Amenemhat, meaning that Senusret was crowned in his father's 33rd regnal year. The name of the younger king is placed ahead of the senior king, which may possibly indicate that Senusret was the dominant personality in the coregency even before his father died, although such speculation is based on far too little evidence for a fair evaluation one way or the other.

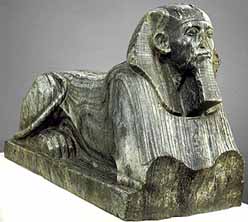

There has been evidence brought forward that shows that the face of the Great Sphinx of Giza is that of Amenemhat II. The evidence includes statements made by German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt suggesting that the eye-paint cosmetics seen on the Sphinx were not seen before the 6th Dynasty (making it unlikely to have represented Khafra as typically assumed) and that the pleated stripes on the nemes headress are in groups of three, a very specific style seen exclusively during the 12th Dynasty.

The same stripes, eye-paint, and facial structure are present on Amenemhat's sphinx statue in the Louvre. It is concluded by this evidence that the statue itself was created during the 4th Dynasty or before, the original head was damaged beyond repair, and that Amenemhat II carved his own likeness into the existing head and neck to save the structure (explaining why the Sphinx's head is so disproportionately small).

Monuments:

Not many buildings from the time of Amenemhat II remain. A pylon at Hermopolis, in Middle Egypt and the foundation deposits at Tod are, along with his pyramid at Dashur, the only notable monuments that were left from his reign.

The choice of location for his pyramid at Dashur, not far from the Bent and Red Pyramids built by 4th Dynasty king Snofru, raises the question why he did not build his funerary monument at El-Lisht like his father and grandfather. It is possible that Amenemhat sought to create a relationship between his dynasty and that of Snofru by doing so.

The pyramid complex is poorly preserved and is mostly known because of the exquisite jewelry that was found in some of the tombs of Amenemhat's daughters, located in the forecourt of the complex. The jewelry included rings, braces, necklaces and diadems and shows the excellent craftsmanship of the era.

From 1894 through 1895, Jacques de Morgan made a cursory investigation of the ruins. Unfortunately he was too focused on the jewelry finds in some surrounding princess' tombs that he never examined the mortuary temple, the causeway or the valley temple. In fact, no casing stones have ever been found nor even the base of the pyramid cleared for a proper measuring. Therefore, we are not sure of its size, the angle of its slop, or its height.

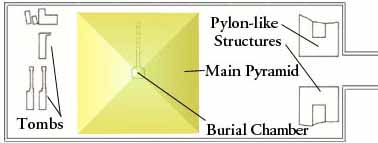

The mortuary temple was almost completely destroyed, though we know it was probably called "Lighted is the place of Amenemhet's pleasures". The ruins, which stand to the east of the pyramid have yet to be closely examined, though they must be very inviting to archaeologists. There are many building fragments, some of which include relief decorations. Most interesting, however, might be the massive, tower-like structures resembling pylons in the temple's east facade.

The causeway, which was broad with a steep slope and enters the enclosure wall on the middle of the east side, has not been investigated at all, and we are told that the valley temple has not even been found. The core of the pyramid was built much like that of Senusret I's pyramid , with a core that had corners radiating out. A framework was made with horizontal lines of blocks to form a grid, or framework between the corners. Here, however, the filling was sand. The entire complex was surrounded by an enclosure wall that was much more rectangular then that found in older pyramids. It was oriented east-west.

Behind the pyramid between it and the west part of the enclosure wall are found tombs of the royal family. The belong to his other son prince Amenemhetankh and princesses Ita, Khnemet, Itiueret and Sithathormeret. Within these tombs, Morgan found the remains of funerary equipment, including wooden coffins, canopic chests and alabaster vessels for perfumes. But of course he also found wonderful jewelry in the tombs of Ita and Khnemet, that stole his attention. These pieces may now be found in the Treasure Chamber of the Cairo Museum.

Books: Genut

We have considerable knowledge of Amenemhet II's reigns because of a number of important documents. Some historical information about the 12th Dynasty comes from a set of official records know as the genut, or 'day-books'.

They were found in the temple at Tod. Some of Amenemhet II's buildings also contain parts of these annals. They describe the day to day process of running the royal palace. One very important set of annuals were discovered at Mit Rahina (a part of ancient Memphis) that record detailed descriptions of donations made to temples, lists of statues and buildings, reports of both military and trading expeditions and even royal activities such as hunting. These documents not only provide information on Amenemhet II, but other kings of the period as well.

The Shipwrecked Sailor

One story during the time of Amenemhet II tells of the travels of a ship captain who had been to a magic island in the sea far south beyond Nubia. The sailor told the vizier (prime minister) about a tempest which arose suddenly and drove the ship towards a mysterious land. He suddenly heard a noise like thunder, and saw a huge serpent with a beard. Upon hearing that the sailor was sent by the pharaoh, the serpent let him go back, with gifts to "Amenemhet". It told him that it was Amon-Ra's blessing that has made this island rich and lacking nothing. Upon hearing this amusing story, "Amenemhet II" ordered it to be documented on a papyrus. The story is known to historians as "The Shipwrecked Sailor".

His name means 'Man of Goddess Wosret' . It was the name that seems to enter the royal linage because of this king's non-royal, great, great grandfather, the original Senusret and father of the founder of the Dynasty, Amenemhet I. Senusret II's name is also found in various references as Senwosret II, or the Greek form, Sesostris II. His throne name was Kha-khaeper-re, meaning "Soul of Re comes into Being".

Khakeperre Senusret II was the fourth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1897 BC to 1878 BC. His pyramid was constructed at El-Lahun. Senusret II took a great deal of interest in the Faiyum oasis region and began work on an extensive irrigation system from Bahr Yusuf through to Lake Moeris through the construction of a dike at El-Lahun and the addition of a network of drainage canals. The purpose of his project was to increase the amount of cultivable land in that area.

The importance of this project is emphasized by Senusret II's decision to move the royal necropolis from Dahshur to El-Lahun where he built his pyramid. This location would remain the political capital for the 12th and 13th Dynasties of Egypt. The king also established the first known workers' quarter in the nearby town of Senusrethotep (Kahun).

Unlike his successor, Senusret II maintained good relations with the various nomarchs or provincial governors of Egypt who were almost as wealthy as the pharaoh. His Year 6 is attested in a wall painting from the tomb of a local nomarch named Khnumhotep at Beni Hasan. It has been speculated that, based on historical dating and the accomplishments of Senusret II, he may be the unnamed Pharaoh mentioned in the biblical story of Joseph.

Of the rulers of this Dynasty, the length of Senusret II's reign is the most debated amongst scholars. The Turin Canon gives an unknown king of the Dynasty a reign of 19 Years, (which is usually attributed to Senusret II), but Senusret II's highest known date is currently only a Year 8 red sandstone stela found in June 1932 in a long unused quarry at Toshka.

Some scholars prefer to ascribe him a reign of only 10 Years and assign the 19 Year reign to Senusret III instead. Other Egyptologists, however, such as Jurgen von Beckerath and Frank Yurco, have maintained the traditional view of a longer 19 Year reign for Senusret II given the level of activity undertaken by the king during his reign. Yurco noted that limiting Senusret II's reign to only 6 or 10 years poses major difficulties because this king

Senusret II may not have shared a coregency with his son, Senusret III, unlike most other Middle Kingdom rulers. Some scholars are of the view that he did, noting a scarab with both kings names inscribed on it, a dedication inscription celebrating the resumption of rituals begun by Senusret II and III, and a papyrus which was thought to mention Senusret II's 19th year and Senusret III's first year.' None of these three items, however, necessitate a coregency. Moreover, the evidence from the papyrus document is now obviated by the fact that the document has been securely dated to Year 19 of Senusret III and Year 1 of Amenemhet III. At present, no document from Senusret II's reign has been discovered from Lahun, the king's new capital city

In 1889, the English Egyptologist Flinders Petrie found "a marvelous gold and inlaid royal uraeus" that must have originally formed part of Senusret II's looted burial equipment in a flooded chamber of the king's pyramid tomb. It is now located in the Cairo Museum. The tomb of Princess Sithathoriunet, a daughter of Senusret II, was also discovered by Egyptologists in a separate burial site. Several pieces of jewellery from her tomb including a pair of pectorals and a crown or diadem were found there. They are now displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of New York or the Cairo Museum in Egypt.

In 2009, Egyptian archaeologists announced the results of new excavations. They described unearthing a cache of pharaonic-era mummies in brightly painted wooden coffins near the Lahun pyramid. The mummies were reportedly the first to be found in the sand-covered desert rock surrounding the pyramid.

Better known then Senusret II's statues are a pair of of highly polished black granite statues of a lady Nefret, who did not carry the title of "Royal Wife", but who was probably either a wife of Senusret II's who

died before he ascended the throne, or a sister.

She did, however, have other

titles usually reserved for queens.

His principal royal wife was Khnumetneferhedjetweret (Weret), who's body was

found in a tomb under the pyramid of her son, Senusret III at Dahshure. Senusret

III would become Senusret II's successor.

So far their is no evidence of

a co-regency with his father as their had been for every king from the time of

Amenemhet I.

Senusret II probably also had several daughters, one of which would

have probably been Sathathoriunet (Sithathoriunet) , who's jewelry was

discovered in a tomb behind the king's pyramid.

Like his father, Senusret II's reign is considered to be a

peaceful one, using more diplomacy with neighbors then warfare. We are told

that trade with the Near East was particularly prolific. His cordial relations

with the regional leaders in Egypt is attested to at Beni Hassan, for example,

and especially in the tomb of Khnumhotep II, who he

gave many honors.

There sem to be no recorded no military campaigns during his rule,

though he undoubted protected Egypt's mineral interests and their expanded

territory in Nubia.

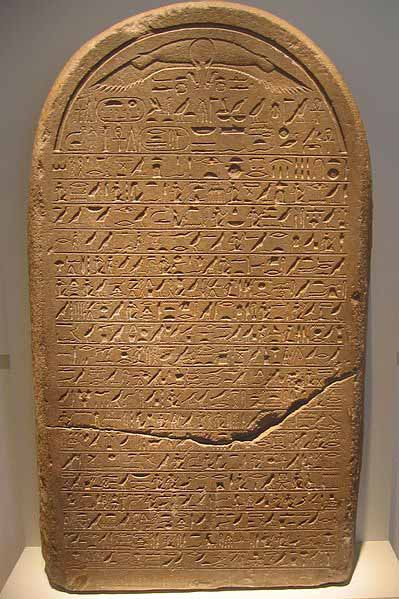

A Stele of Senusret II in Brown Quartzite

His efforts seem to have been more directed at expanding cultivation within

the Fayoum rather then making war

with his neighbors and regional nobles.

In the Fayoum, his projects turned a

considerable area from marshlands into agricultural land. He established a

Fayoum irrigation project, including building a dyke and digging canals to

connect the Fayoum with a waterway known today as Bahr Yusef.

He seems to have had a great interest in the Fayoum, and elevated the region

in importance. Its growing recognition is attested to by a number of pyramids

built before, and after his reign in or near the oasis (though the Fayoum is not

a true oasis). It should also be remembered that kings usually built their royal

palaces near their mortuary complexes, so it is likely that many of the future

kings made their home in the Fayoum.

These later kings would also continued and

expanded upon Senusret II's irrigation projects in the Fayoum. Senusret II built

a unique statue shrine of Qasr es-Sagha on the north eastern corner of the

region, though it was left undecorated and incomplete.

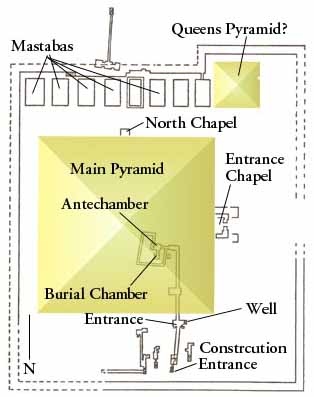

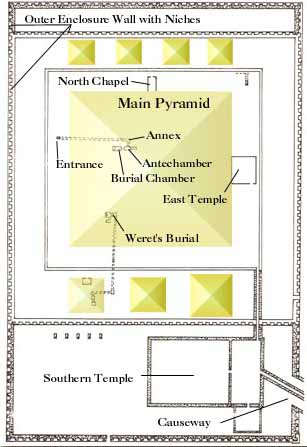

Senusret II's Pyramid

His father, Amenemhet II built his pyramid at Dahshure, but Senusret II built

his pyramid closer to the Fayoum Oasis at Lahun.

His pyramid definitely established a

new tradition in pyramid building, perhaps begun by his father.

Senusret II chose to build his pyramid, called Senusret Shines, near the modern town of Lahun (Kahun)

at the opening of the Hawara basin near the Fayoum rather then at Dahshure where his father's Amenemhet II pyramid

is located.

The location of Senusret II's valley temple is known but no ground plan can

be made from its ruins. The causeway is likewise ruined, but must have been

broad, and of the completely destroyed mortuary temple on the east side of the

pyramid, all that is known is that it must have been built of decorated granite,

judging from the few fragments that remain.

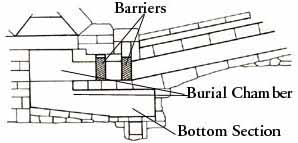

Beginning with Senusret II, the location of the door was less important

from a religious then from a security standpoint, so rather then being on the

north side of the structure, it was hidden in the pavement of the south side.

To the south side of the pyramid Petrie excavated four shaft tombs that

belonged to Senusret II's family and in one of these, discovered a fine, gold

inlaid uraeus that may have come from the king's mummy.

In building this pyramid Senusret II's archetects took advantage of a natural

stump of yellow limestone that they cut down into four steps to serve as the

pyramid's base core. Mudbrick was used to build the upper part of the core, and

as several pyramids before, wings were built out from this core and cross walls

within the wings were built to form a framework.

The resulting sections were

then filled with mudbrick. Also like some prior 12th

Dynasty pyramids, the casing was set into a foundation trench at the base of

the pyramid. Most of the casing was carried off to build a structure for Ramesses

II, though parts of the black granite pyramidion

that set atop the pyramid have been found. There was also a cobble filled

drainage ditch around the pyramid that was filled with sand to channel rain

water.

While the pyramid had been robbed in antiquity, it nevertheless took Petrie

months to located the entrance to this pyramid. The reason is that for the first

time, the builder's were more interested in security then religious tradition,

and therefore hid the entry passage in the pavement of the pyramid courtyard

near the east end of the pyramid's south side.

Prior to this, just about all

pyramid entrances were in the middle of the north side. This was because in the

astral and celestial religion of the old kingdom, the king was to leave his tomb

to the north where he was himself to become both a star and a deity.

However, because of the rise in the cult of Osiris,

this became less important, and it was more meaningful for the tomb to resemble

the underworld of Osiris.

Interestingly, the builders of the pyramid must have thought this would be

sufficient insurance against thieves, as they did not even include a barrier in

the entrance corridor.

Also interesting is the "entrance chapel, not

located above the entrance, or on the north side of the pyramid (these are also

typically referred to as "North Chapels").

It was located in the

middle of the east wall of the pyramid. However, there was actually a

north chapel, though smaller and less structurally similar to older north

chapels then the entrance chapel on the east side of the pyramid. The vaulted entrance corridor was too narrow for a large sarcophagus and the

blocks used to line the burial chamber, though another entrance was hidden

farther south, beneath a sloping passage to the tomb of an unknown princess.

This shaft is about 16 meters (52 feet) deep, and a corridor at the bottom leads

to an entrance hall below the formal entrance shaft.

The hall has a vaulted

ceiling and a niche at the east end of the hall contains a ritual well, the

bottom of which has never been reached. It drops to at least the water table.

Because ritual shafts did not become prominent until much later, some

Egyptologists maintain that the shaft may have been built to monitor the ground

water, or for other unknown purposes.

After the entrance hall another corridor gradually rises before passing

through a chamber to the left and finally arriving at an antechamber. From the

antechamber, the substructure takes a 90 degree left turn, passing through a

short corridor to the burial chamber, which lies under the southeast quadrant of

the pyramid. The burial chamber is sheathed in granite and has a gabled roof. A

red granite sarcophagus fills the west end of the chamber. Before it stood an

alabaster offering table.

From the southeast corner of the burial chamber a short corridor leads to a

small side chamber where leg bones, presumably of the king, were found. At the

northwest corner at the head of the sarcophagus is the entrance to a passage

that loops around the burial chamber to a doorway in the short corridor between

the antechamber and the burial chamber.

This corridor presented a symbolic exit to the north for the king's spirit. But it

also creates a symbolic subterranean island that can be related to the god,

Osiris, who's worship was on the rise during the 12th Dynasty.

In addition to the tombs of the princesses to the southeast, between the pyramid and the north section of the enclosure wall, eight mastabas were built using mudbrick to cover a superstructure carved from the bedrock, similar to the manner in which the pyramid was built.

A small pyramid lies at the north end of this row of mastabas, thought to be that of a queen. If it is not the pyramid of a queen, but an unlikely cult pyramid, it would have been the last such structure built, rather then that of his grandfather's, Senusret I. Though this pyramid does have a North Chapel, Petrie never found a subterranean structure even after exhaustive investigation.

The only evidence we do have that the pyramid belonged to a queen is its placement within the complex and a partial name from a vase that Petrie found in a foundation deposit.

West of the entrance shaft of the pyramid Petrie discovered the ruins of the tomb of Princess Sathathoriunet (Sithathoriunet), where he discovered the famous Treasure of el-Lahun, which included wonderful jewelry and other items from the her burial equipment.

These items included a gold headband, a gold necklace of small leopard's heads, two gold pectorial ornamented with precious stones one of which was inscribed with Senusret II's name and the second with the name of Amenemhet III. There were also other bracelets, rings and alabaster and obsidian vessels that were decorated with gold, all of which today can be found in the Egyptian Antiquities Museum.

Nearby the complex to the northwest lies the ruins of the pyramid town that grew up around the construction of Senusret II's pyramid. Coriginally named Hetep Senusret, meaning "May Senusret be at Peace". It has provided considerable information to Egyptologists on the lives of common Egyptians and urbanism. This ancient village is today known as Lahun, or Kahun, after the local nearby village.

Senusret II is further attested to by a sphinx, now in the Egyptian Antiquity Museum in Cairo and by inscriptions of both he and his father near Aswan.

It should also be mentioned that the pyramid town associated with Senusret II's complex, known as Lahun (Kahun) after the nearby modern village, provided considerable information to archaeologists and Egyptologists on the common lives of Egyptians. Pyramid towns were communities of workmen, craftsmen and administrators that grew up around a king's pyramid project.

Khakhaure Senusret III (also written as Senwosret III or Sesostris III) was a pharaoh of Egypt. He ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC, and was the fifth monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. Among his achievements was the building of the Sisostris Canal. He was a great pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty and is considered to be perhaps the most powerful Egyptian ruler of the dynasty. Consequently, he is regarded as one of the sources for the legend about Sesostris. His military campaigns gave rise to an era of peace and economic prosperity that reduced the power of regional rulers and led to a revival in craftwork, trade and urban development. Senusret III was one of the few kings who were deified and honored with a cult during their own lifetime.

Senusret III cleared a navigable canal through the first cataract and relentlessly pushed his kingdom's expansion into Nubia (from 1866 to 1863 BC) where he erected massive river forts including Buhen, Semna and Toshka at Uronarti.

He carried out at least four major campaigns into Nubia in his Year 8, 10, 16 and 19 respectively. His Year 8 stela at Semna documents his victories against the Nubians through which he is thought to have made safe the southern frontier, preventing further incursions into Egypt. Another great stela from Semna dated to the third month of Year 16 of his reign mentions his military activities against both Nubia and Canaan. In it, he admonished his future successors to maintain the new border which he had created

Wegner stresses that it is unlikely that Amenemhet III, Senusret's son and successor would still be working on his father's temple nearly 4 decades into his own reign. He notes that the only possible solution for the block's existence here is that Senusret III had a 39-year reign, with the final 20 years in coregency with his son Amenemhet III. Since the project was associated with a project of Senusret III, his Regnal Year was presumably used to date the block, rather than Year 20 of Amenemhet III. This implies that Senusret was still alive in the first two decades of his son's reign.

Visually, Senusret III is known for his strikingly somber sculptures in which he appears careworn and grave.

His court included the viziers Sobekemhat, Nebit and Khnumhotep. Ikhernofret worked as treasurer for the king at Abydos. Senankh cleared the canal at Sehel for the king.

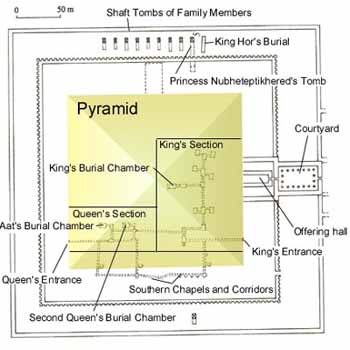

Senusret III had his pyramid built at Dahshur, a mostly Middle Kingdom necropolis. It was the largest of the 12th Dynasty pyramids, but like the others with mudbrick cores, after the casing was removed it deteriorated badly.

In the excavation season of 1894-1895, Jacques de Morgan also found the tombs of Queen Mereret and princess Sit-Hathor near the northern enclosure wall of Senusret III's pyramid complex. Also found with these tombs were some fine jewelry, missed by earlier robbers.

Some Egyptologists doubt that Senusret III was buried in this pyramid. He also had an elaborate tomb and complex built in South Abydos. This huge complex stretches over a kilometer between the edge of the Nile floodplain and the foot of the high desert cliffs that form the western boundary of the valley. This complex consists of an underground tomb which, at least at one time, was considered to be the largest in Egypt - that may have been eclipsed by the discovery of the Tomb of Ramesses II's Sons in the Valley of the Kings.

Other components include a mortuary temple at the edge of the cultivated fields and a town south of the tomb that supported the complex. The name of this funerary complex was 'Enduring are the Places of Khakaure Justified in Abydos'.

Senusret III is further attested by blocks from a doorway found near Qantir and by his rock inscriptions near the island of Sehel south of Aswan that record the reopening of the bypass canal.

The sixth ruler of the 12th Dynasty

Amenemhat III, also spelled Amenemhet III was a pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from c.1860 BC to c.1814 BC, the latest known date being found in a papyrus dated to Regnal Year 46, I Akhet 22 of his rule. He is regarded as the greatest monarch of the Middle Kingdom.[citation needed] He may have had a long coregency (of 20 years) with his father, Senusret III.

Towards the end of his reign he instituted a coregency with his successor Amenemhet IV, as recorded in a now damaged rock inscription at Konosso in Nubia, which equates Year 1 of Amenemhet IV to either Year 46, 47 or 48 of his reign. His daughter, Sobekneferu, later succeeded Amenemhat IV, as the last ruler of the 12th Dynasty. Amenemhat III's throne name, Nimaatre, means "Belonging to the Justice of Re."

He built his first pyramid at Dahshur (the so-called "Black Pyramid") but there were construction problems and this was abandoned. Around Year 15 of his reign the king decided to build a new pyramid at Hawara The pyramid at Dahshur was used as burial ground for several royal women.

His mortuary temple at Hawara (near the Fayum), is accompanied by a pyramid and may have been known to Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus as the "Labyrinth".[6] Strabo praised it as a wonder of the world. The king's pyramid at Hawara contained some of the most complex security features of any found in Egypt and is perhaps the only one to come close to the sort of tricks Hollywood associates with such structures. Nevertheless, the king's burial was robbed in antiquity. His daughter, Neferuptah, was buried in a separate pyramid (discovered in 1956) 2 km southwest of the king's The pyramidion of Amenemhet III's pyramid tomb was found toppled from the peak of its structure and preserved relatively intact; it is today located in the Egyptian Cairo Museum.

The vizier Kheti held this office around year 29 of king Amenemhet III's reign. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus is thought to have been originally composed during Amenemhat's time. The monuments of Amenemhat III are fairly numerous and of excellent quality. This includes a small, but well decorated, temple of Medinet Maadi in the Faiyum which he and his father dedicated to the harvest goddess Renenutet.

What we do not see during Amenemhet III's time is a lot of military action, other then perhaps strengthening the defenses at Semna. The military activities of his predecessors allowed him a peaceful reign upon which to build, as well as to exploit the mineral wealth of the quarries. He does build, politically, reorganizing the domestic administration. He continued to reform the national administration as did his father. It was probably his father that divided the country into three administrative regions, controlled by departments based at the capital. This federal bureaucracy oversaw the activities of local officials, who no longer possessed any extensive power. Amenemhet III continued to refine this new administration.

Amenemhet III was also able to continue with good foreign relations also without much military action. It is said that he was honored and respected from Kerma to Byblos, and during his reign many eastern workers, including peasants, soldiers and craftsmen, came to Egypt.

However, the extensive building works, together with possibly a series of low Nile floods, may have exhausted the economy by the end of his reign. Ironically, all of these foreign workers, many employed for building activities, may have also encouraged the Hyksos to settle in the Delta, thus leading eventually to the collapse of native Egyptian rule. Upon the king's death, he was buried in his second pyramid at Hawara.

Amenemhet III is also attested to by an unusual set of statues probably of Amenemhet III and Senusret III that shows the two in archaic priestly dress and offering fish, lotus flowers and geese. These statues are very naturalistic. but show the king in the guise of a Nile god.. There was also a set of sphinxes that were once thought to have been attributable to the later Hyksos rulers, but are now believed to have been built on the orders of Amenemhet III. Originally all these statues were discovered reused in the Third Intermediate Period temples at Tanis. We also know of an inscription by the king at Koptos(Coptos).

Amenemhet III attempted to build his first pyramid at Dahshur, but it turned out to be a disaster as it was built on unstable subsoil. Today the pyramid named 'Amenemhet is Mighty' is a sad dark ruin on the Dahshur field, aptly sometimes called the Black Pyramid.

Even though it took 15 years to build, rather then being buried in this pyramid, Amenemhet III chose to build a second pyramid at Hawara, closer to his beloved Fayoum.

Amenemhat IV, or Amenemhet IV was Pharaoh of Egypt, likely ruling between ca. 1815 BC and ca. 1806 BC. He served first as the junior coregent of Amenemhat III and completed the latter's temple at Medinet Maadi, which is "the only intact temple still existing from the Middle Kingdom" according to Zahi Hawass, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA). The temple's foundations, administrative buildings, granaries and residences were recently uncovered by an Egyptian archaeological expedition in early 2006. Amenemhat IV likely also built a temple in the northeastern Fayum at Qasr el-Sagha.

The Turin Canon papyrus records a reign of 9 Years 3 months and 27 days for Amenemhat IV. He served the first year of his reign as the junior co-regent to his powerful predecessor, Amenemhat III, according to a rock graffito in Nubia. His short reign was relatively peaceful and uneventful; several dated expeditions were recorded at the Serabit el-Khadim mines in the Sinai. It was after his death that the gradual decline of the Middle Kingdom is thought to have begun.

Amenemhat died without a male heir, though it is possible that the two first rulers of the next dynasty, Sobekhotep I and Sonbef were his sons. He was succeeded by his half-sister (or perhaps his aunt) Sobeknefru, who became the first woman in about 1500 years to rule Egypt. He may have been Sobeknefru's spouse but no historical evidence currently substantiates this theory.

Sobekneferu (sometimes written "Neferusobek") was an Egyptian pharaoh of the twelfth dynasty. Her name meant "the beauty of Sobek." She was the daughter of Pharaoh Amenemhat III. Manetho states she also was the sister of Amenemhat IV, but this claim is unproven. Sobekneferu had an older sister named Nefruptah who may have been the intended heir. Neferuptah's name was enclosed in a cartouche and she had her own pyramid at Hawara. Neferuptah died at an early age however.

Sobekneferu is the first known female ruler of Egypt, although Nitocris may have ruled in the Sixth Dynasty, and there are five other women who are believed to have ruled as early as the First Dynasty.

Amenemhat IV most likely died without a male heir; consequently, Amenemhat III's royal daughter Sobekneferu assumed the throne. According to the Turin Canon, she ruled for 3 years, 10 months, and 24 days in the late 19th century BC. She died without heirs and the end of her reign concluded Egypt's brilliant Twelfth Dynasty and the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom as it inaugurated the much weaker Thirteenth Dynasty.