There have been various stories about the origin of the Chinese script, with nearly all ancient writers attributing it to a man named Cangjie. Cangjie, according to one legend, saw a divine being whose face had unusual features that looked like a picture of writings. In imitation of his image, Cangjie created the earliest written characters. After that, certain ancient accounts go on to say, millet rained from heaven and the spirits howled every night to lament the leakage of the divine secret of writing.

Another story says that Cangjie saw the footprints of birds and beasts, which inspired him to create written characters.

Evidently these stories cannot be accepted as the truth, for any script can only be a creation developed by the masses of the people to meet the needs of social life over a long period of trial and experiment. Cangjie, if there ever was such a man, must have been a prehistoric wise man who sorted out and standardized the characters that had already been in use.

A group of ancient tombs have been discovered in recent years at Yanghe in Luxian County, Shandong Province. They date back 4,500 years and belong to a late period of the Dawenkou Culture. Among the large numbers of relics unearthed are about a dozen pottery wine vessels (called zun), which bear a character each. These characters are found to be stylized pictures of some physical objects. They are therefore called pictographs and, in style and structure, are already quite close to the inscriptions on the oracle bones and shells, though they antedate the latter by more than a thousand years.

The pictographs, the earliest forms of Chinese written characters, already possessed the characteristics of a script.

As is well known, written Chinese is not an alphabetic language, but a script of ideograms. Their formation follows three principles:

These picture-words underwent a gradual evolution over the centuries until the pictographs changed into "square characters," some simplified by losing certain strokes and others made more complicated but, as a whole, from irregular drawings they became stylized forms.

The principle of forming characters by drawing pictures is easy to understand, but pictographs cannot express abstract ideas. So the ancients invented the "associative compounds," i. e., characters formed by combining two or more elements, each with a meaning of its own, to express new ideas.

Though pictographs and associative compounds indicate the meanings of characters by their forms, yet neither of the two categories gives any hint as to pronunciation. The pictophonetic method was developed to create new characters by combining one element indicating meaning and the other sound.

The characters stand for things or ideas and so, unlike groups of letters, they cannot and need never be sounded. Thus Chinese could be read by people in all parts of the country in spite of gradual changes in pronunciation, the emergence of regional and local dialects, and modification of the characters.

There are two elements to the Chinese language: the written language, based on individual symbols called characters, each of which represents an idea or thing; and the spoken language, which includes a number of different dialects. The written language originally had no alphabet, but it was easily understood by literate people no matter what dialect they spoke.

Since the early 1950s a system using the Latin alphabet, called Pinyin, has been developed in China, and it is now in common use. Most of the spellings of Chinese sounds and names in this article are based on the Pinyin system of romanization. Those that are not are generally very familiar in their conventional form, such as the name Chiang Kai-shek.

Some of the numerous dialects of spoken Chinese are totally different from each other. All of them use tones to distinguish different words. Mandarin, which is spoken in the Beijing region and in northern China generally, has four common tones. Cantonese, spoken in southeastern China, has nine tones and is quite different from Mandarin.

Today Putonghua, which is based on Beijing-area Mandarin, is the official language of government and education, and everyone is expected to learn to speak it. The central government is also expanding the use of the Pinyin romanization system and is urging citizens to learn this alphabetized system of writing Chinese words. (Pinyin represents the spoken sounds of Putonghua, which is an oral representation of Chinese characters.) Citizens are also urged to learn a simplified system of Chinese.

Western alphabets have anywhere between 20 and 50 letters.

Unlike other scripts with non-latin character sets, Chinese characters are virtually unlimited in number. Moreover, they do not simply stand for sounds like the letters of western alphabets.

Chinese writing does not have an alphabet, instead, they are using symbols, or Chinese characters (hanzi in Chinese, kanji in Japanese).

These characters are based on a phonetic instead of a semantic system, that is, their primary function is to represent not sound but meaning. This is why their number is much larger than the number of letters in an alphabet.

In Chinese, every character is a syllable. It seems that originally Chinese language was monosyllabic, in other words, words consisted only of a single syllable.

Starting around the beginning of the Han dynasty (3rd century BC) the language started to use more and more words with two or more syllables but by that time the structure of writing has been already fully developed.

Therefore, the structure of writing system reflects the original monosyllabic stage. This means that, at least in general, there was a symbol constructed for every word. Because of this, the number of elements in the script is not based on the number of sounds but on the number of words in the language.

And, as we all know, the number of words is very large in any language.

Because of this, the number of characters in Chinese writing is very high. It is estimated that to read a newspaper, one must learn about 3,000 characters.

The Shuowen jiezi, the first surviving Chinese dictionary complied by Xu Shen around 100 AD contains over 9,000 characters, the Kangxi zidian from the 18th century has nearly 47,000. The largest modern dictionaries have over 60,000. Though many of these symbols are never used, they are still part of the Chinese script.

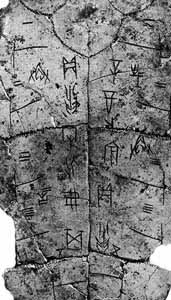

The earliest examples of Chinese writing date to the late Shang period (ca. 1200 BC). These are the so-called Oracle Bone Inscriptions (jiaguwen) which were found at the site of the last Shang capital near present-day Anyang, Henan province.

The discovery of the oracle bones in China goes back to 1899, when a scholar from Peking was prescribed a remedy containing "dragon bones" for his illness: "dragon bones" were widely used in Chinese medicine and usually refer to fossils of dead animals. The scholar noticed some carvings that looked like some kind of writing on the bones he acquired from the local pharmacy. This lucky find led eventually to the discovery of Anyang, the last capital of Shang dynasty where archeologists have found an enormous amount of these carved bones.

The inscriptions on these bones tell us that by 1200 BC Chinese writing was already a highly developed writing system which was used to record a language fairly similar to classical Chinese. Such a complex and sophisticated script certainly has a history but so far we found no traces of its predecessors.

The oracle bone inscriptions received their name after their content which is invariably related to divination. The ancient Chinese diviners used these bones as records of their activity, providing us with a detailed description of the topics that interested the Shang kings. Most of these divinations refer to hunting, warfare, weather, selection of auspicious days for ceremonies, etc.

Oracle bones: 3,250-year-old engraved bones and tortoise shells from ancient China were used to foretell the future Live Science - November 11, 2024

There is no one "oracle bone" - about 13,000 have been found - but these relics hint at the development of writing in ancient China. They date from the late Shang Dynasty, (circa 1250 B.C. to circa 1050 B.C.), although the Bronze Age Shang Dynasty ruled most of northern China from about 1600 B.C. - the earliest traditional Chinese dynasty for which there is archaeological evidence.

According to Chinese scholars, oracle bone artifacts were often dug up by later farmers in the former Shang territories, and many were exhumed during burial ceremonies in the former Shang capital of Anyang, in China's Henan province. In the 19th century, villagers near Anyang unearthed oracle bones they thought were "dragon bones" and large numbers were ground-up for traditional medicine until they became valuable to antique dealers.

Oracle bones were often made from tortoise shells, as in this photograph, and from the shoulder blades of oxen. According to archaeologists, a fortune teller would carve a question into the bone with a sharp implement, and then heat it until it cracked; they then claimed to interpret the cracks.

The bones and shells were reused until there was no more space, and so more than 100,000 inscriptions are known.

The surviving oracle bones are the earliest existing form of Chinese writing. Many of the roughly 5,000 characters in the "oracle bone script" are still used in modern Chinese (some versions of Chinese recognize tens of thousands of written characters) although some characters are still not well understood. They were also used in divinations for the Shang royal household, and scholars have used them to chart the Shang royal genealogy.

Oracle bones predating the Shang Dynasty have also been found, and in 2003, some archaeologists said they'd found "Neolithic oracle bones" from up to 8,600 years ago.

Early reports claimed that some of their characters were the same as Shang characters. But other experts doubted the claims, noting it was unlikely that any Shang characters were used more than 5,000 years earlier than thought.

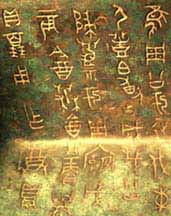

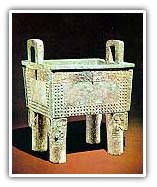

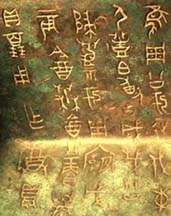

The next stage in the history of Chinese writing is the bronze inscriptions (jinwen). These are texts either casted into bronze vessels or carved into the surface of an already carved vessel. These vessels became widely used during the Eastern Zhou dynasty (ca. 1150-771 BC) but there are examples from late Shang as well.

Since the inscriptions are located on ritual vessels which were used for performing sacrifices, their content usually refers to ritual ceremonies, commemorations etc. Although most of these writings consist of only a few characters, there are some which contain quite lengthy descriptions. The language and calligraphic style at this stage is similar to that found on the oracle bones.

The earliest examples of Chinese writing date to the late Shang period (ca. 1200 BC). These are the so-called Oracle Bone Inscriptions (jiaguwen) which were found at the site of the last Shang capital near present-day Anyang, Henan province. Another type of early Chinese script in its long history of development is represented by the inscriptions cast or carved on ancient bronze objects of the Shang and Zhou dynasties. It is called .Jinwen (literally, script on metal) and, as ancient bronzes arc generally referred to as zhongding (bells and tripods) it is also called zhongdingmen.

The ding, originally a big cooking pot with three (rarely four) legs, became a ritual object and a sign of power, and the owning of such tripods, as 41 as their sizes and numbers, was a status symbol of the Shang slave-owning aristocrats. At the beginning only the names of the owners were cast or engraved on the tripods. Later the tripods (and other bronzes) began to carry longer inscriptions stating the uses they were put to and the dates they were cast. Towards the end of the Warring States Period (475 221 B. C.) - the ducal states of Zheng and Jin had their statutes promulgated and cast on tripods.

Thus the inscriptions on the bronzes grew longer, from a few characters to a few hundred, from simple phrases to detailed accounts. Many bronze objects bearing inscriptions have been unearthed in China and can be seen in a large number of museums.

A priceless tripod is the Daynding (Large Tripod Bestowed upon Yu) dating from the early Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century to 771 B. C.), now kept at the Museum of Chinese History in Beijing. About one meter high and weighing 153. 5 kilograms, it has on its interior wall an inscription of 291 characters in 19 lines, by which King Kang summed up the experience in founding a new nation and drew lessons from the failure of the preceding Shang Dynasty. The inscription also mentions that the King awarded his aristocrat follower Yu 1, 722 slaves of various grades and large numbers of carriages and horses.

Another important bronze called Maogongding, now kept in Taiwan Province, belongs to the late Western Zhou. It bears an inscription of 497 characters, the longest ever discovered on any bronze hitherto unearthed. It is an account of how King Xuan admonished, commended and awarded Maogong Yin; it also reveals the instability of the Western Zhou regime at the time. Both tripods furnish rare and valuable information to throw light on the slave society under the Western Zhou.

The ancient bronzes reflect not only the high level that Chinese metallurgy attained in their time. The inscriptions they bear may well be regarded as "books in bronze" which fill important gaps left by the scanty written history of that remote age.

Starting from about the fifth century BC, we begin to find examples of writings on bamboo strips. Before writing the characters with a hard brush or a stick on the bamboo surface, the strips were prepared in advance and tied together with strings to form a roll.

The new media also means new content: along with historical and administrative writings, the bamboo strips contains the earliest manuscripts of famous Chinese philosophical texts, such as the Laozi, Liji, and Lunyu. Beside bamboo, texts were also written on wooden tablets and silk cloth.

The written language by this time is the so-called "classical Chinese" (wenyan) which had remained more or less the same as late as the 19th century.

A major event in the history of Chinese script is the standardization of writing by the First Emperor of Qin who unified China in 221 BC. Before that time, each of the many states in China had their own style and peculiarities which meant that, although mutually comprehensible, the scripts had many deviations. The First Emperor introduced the Qin script as the official writing and from there on all the unified states had to use it in their affairs. The calligraphic style of this period is the "clerical script" or lishu which is easily readable today even to the uninitiated.

In museums of ancient history one often sees bamboo or wood strips written with characters by the writing brush. These slips are called jian, the earliest form of books in China.

The practice of writing on slips began probably during the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th-11th century B. C.) and lasted till the Eastern Han (AI) 25-220), extending over a period of 1,600 - 1,700 years. The historical Records, the first monumental general history written by the great historian Sima Qian (c. 110 B.C. - ?), consisting of 520,000 characters in 130 chapters and covering a period of 3,000 years from the legendary Yellow Emperor to Emperor Wudi of the Han, was written on slips. So were other well known works of ancient China, including the Book of Songs (the earliest Chinese anthology of poems and songs from 11th century to about 600 B. C.) and Jiazhang Suanshu (Mathematics in Nine Chapters completed in the 1st century AD, the earliest book on mathematics in the country).

Excavations in 1972 in an ancient tomb of the Western Han Dynasty (206 B. C. -A. D. 24) at Yinque Mountain, Linyi, Shandong Province brought to light 4,924 bamboo slips. They turned out to be hand-written, though incomplete, copies of two of China's earliest books on military strategy and tactics The Art of War by Sun Zi and The Art of War by Sun Bin. The latter had been missing for at least 1,400 years.

To write on bamboo or wood slips was no easy task. Take bamboo slips for example. Bamboos were first cut into sections and then into strips. These were dried by fire to be drained of the moisture of the natural plant to prevent rotting and worm- eating in future. The finished bamboo slips run from 20 to 70 cm in length. Judging from those unearthed from ancient tombs, royal decrees and statutes were written on slips 68 cm long, texts of the classics on 56-cm-long slips, and private letters on 23 cm ones. The brush was used in writing and, in case of mistakes, the wrong characters would be scraped off by means of a small knife to allow the correct ones to be filled in. The knife played the same role as the rubber eraser today.

Writing on bamboo or wood slips was done from top to bottom, with each line comprising from 10 to at most 40 characters. To write a work of some length, one would need thousands of slips. The written slips would then be bound together with strips into a book. Some books were so heavy that they had to be carried in carts. In some cases the blank slips were first bound into books before they were written on.

An unofficial story tells about Dongfang Shuo (154-93 B. C.), a courtier and humorist, who wrote a 30,000 -character memorial to the Western Han Emperor Wudi, using more than 3,000 slips. These had to be carried by two men to the audience hall.

Legend also extols the hard work of the First Emperor of the Qin of 2,200 years ago by telling that he had to peruse and comment on 60 kilograms of official documents every day. This may not be so astonishing as at first hearing, when one recalls that the passages were written on wood or bamboo slips.

Heavy and clumsy as they were, ancient books of bamboo and wood played an important part in the dissemination of knowledge in various fields. They were in circulation over a long period until gradually replaced by paper which was invented in the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 23-220).

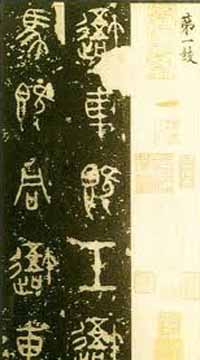

Shigawen, the earliest Chinese script cut on stone, is kept in the Palace Museum (Forbidden City) of Beijing. It is in the form of inscriptions, on 10 drum-shaped stone blocks, of 10 poems of 4 character lines, depicting the ruler of a state on a big hunt. The characters are written in a style called dazhuan (big seal character) and have been taken as the "earliest model of zhuan-style writing", important to the development and studies of Chinese calligraphy.

The "stone drums" were discovered in the Tang Dynasty (Al) 618-907) at Tianxing (present-day Baoji in Shaanxi Province) and caused a stir among men of letters and calligraphers. Celebrated poets like Du Fu, Han Yu and Su Dongpo sang of the discovery in verse. It was only after the end of World War 11 that the "stone drums" were moved to Beijing for safekeeping. But age, rough handling and long distance bans port have told on the valuable relics. Many of the characters have disappeared or eroded by weathering, and one of the "drums" has even become completely devoid of any engraving.

Before the invention of paper and printing, the best way in China to keep outstanding writings and calligraphic works was to carve them on stone. Those cut on drum shaped blocks are called shigawen (stone drum inscriptions); and those cut on steles and tablets are called beimen. The former, being much earlier and rarer, are greatly treasured.

The dating of the set of stone drums under discussion was a subject of controversy over the ages. Careful research made by archaeologists in recent years has led to the conclusion that they were engraved in the state of Qin during the Warring States Period (475-221 B. C. ) and are therefore well over 2,000 years old.

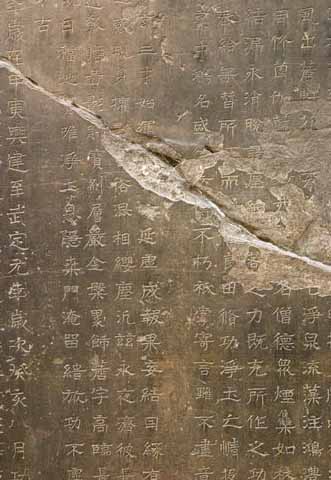

Before the invention of the art of printing, how did ancient Chinese preserve and disseminate their culture and art? As mentioned before, they relied to a great extent upon inscriptions on stone tablets.

These inscriptions are known as beiwen (writings on stelae) or, less common, shishu (stone books). The earliest examples so far discovered are a set of 46 stelae engraved with the Confucian classics after the handwriting of the great Eastern Han calligrapher Cai Yong, carved in Al) 175 or the fourth year in the reign of Xiping. They are called "Xiping Shijing" (Xiping Classics on Stone). They were stood in front of the lecture halls of the then Imperial College in old 1 uoyang (the site of the 3rd-century town, a little to the east of today's Luoyang) as standard versions of the classics for the students to read or to copy from.

To engrave a voluminous work or series of works would require thousands of stone tablets and generations of perseverance and painstaking work. By far the greatest work engraved on stone is the Dazangjing (Great Buddhist Scriptures), which comprises more than 14,000 tablets. The carving of the stupendous collection began in the Sui Dynasty (581-618) and concluded about 1644, when the The Qing, extending over a thousand years, replaced Ming Dynasty! This rare collection of books on stone is kept in 9 rocky caves on Shijingshan (Stone Scripture Mountain) in Fangshan County, southwest of Beijing.

In order to preserve the "stone books" of various periods, scholars in China started as early as 1090 (5th year of the Yuanyou Period under the Song Dynasty) to collect the stelae scattered around the country and keep them together at Xi'an. Today in the halls of the "Forest of Stelae" are 1,700 tablets of many dynasties from the Han down to the Qing - the greatest collection in China.

The engravings on these stones cover a wide range of subjects-from the classics to works of calligraphy, from linear drawings to pictures in low relief. They include the Thirteen Classics (Book of Changes, Book of History, Book of' Songs, the Analects, etc.), the basic readings required of Confucian scholars of past ages. These, totaling 650,252 characters, were cut on both sides of 114 stelae in A.1). 837 of the Tang Dynasty. The stelae stand side by side like walls of stone, a veritable library of stone books.

The Forest of Stelae at Xi'an is not only a treasure house of Chinese literature and history but represents, a galaxy of the best calligraphers of different ages and schools, including all the different scripts-zhuan seal character, li (official script), coo (cursive) and kai (regular) -each with its representative works. Visitors here may feast their eyes on the whole gamut of Chinese calligraphy.

From sometime in the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) and over a long period of time in ancient China, plain silk of various descriptions joined bamboo and wood slips as the material for writing or painting on. Silk had advantages over the slips in that it was much lighter and could be cut in desired shapes and sizes and folded, the better to be kept and carried. But owing to its much greater cost, silk was never so popularly used as the slips.

The most valuable find of ancient silk writings was made in 1973 from an ancient tomb known as the No. 3 Han Tomb at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province. It is in the form of 30-odd pieces of silk, bearing more than 120,000 characters. They consist largely of ancient works that had long been lost. For instance, Wuxingzhan describes the orbits of five planets (Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars and Saturn) and gives the cycles of their alignment, all with a precision far more remarkable than similar works that appeared later. Also found were three maps drawn on silk, showing the topography, the stationing of troops and the cities and towns of certain regions of China.

They are the earliest maps in China, and in the world as well, that have been made on the basis of field surveys. Contrary to their modern counterparts, they show south on top and north at the bottom. The topographic map is at a scale of 1:180,00), and the troop distribution map at about 1: 80, 000/100, 000. Their historical value may be easily imagined when one remembers that they are at least 2,100 years old.

Silk was considered in old China an exquisite material for writing on; some were pre-marked with lines in vermilion. During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), it was the fashion to weave the lines into plain white silk to be used exclusively for writing. Many artists of today have carried on the ancient practice of painting and writing on silk.

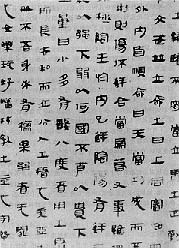

To make rubbings from carved inscriptions was the earliest method of making copies in China before printing was invented.

In ancient times, engravings were often made on stone of important imperial decrees, texts of Confucian classics, Buddhist scriptures, proved medical recipes as well as poems, pictures and calligraphic works by noted men of letters so that they may be appreciated and preserved for posterity.

To make rubbings is to make copies from these cut inscriptions or pictures. The method followed is rather simple in principle paste a wetted piece of soft but firm paper (xuan paper is normally used) closely over the stone tablet or bronze and beat it lightly all over with the cushioned end of a stick so that the parts of paper over the cut hollows will sink in. The paper is then left on to dry. Then ink is applied by dabbing it on until the paper is turned into a copy with white characters or drawings on a black ground. Removed and dried, it becomes the rubbing.

Rubbings vary and are called by different names according to the ink used. Wujinta (black gold rubbings) are made with very black ink; chanyita (cicada wing rubbings) are made with very light ink; zhuta (vermilion rubbings) with vermilion ink. With the bound book form, the rubbings become beitie (stele rubbings), which may be used either as models for calligraphy or kept in a collection for appreciation or research. As inscriptions on bronze, stone or wood wear out with time, early rubbings made from famous pieces of work are more valued and cherished than the ones made later. Rubbings are convenient and meaningful mementoes for foreign tourists to remind them of their China tours. They are especially liked by Japanese visitors who share the same written character. Read more...