In 329 BC in Central Asia Alexander the Great recorded two great flying silver shields, spitting fire around the rims in the sky that dived repeatedly at his army as they were attempting a river crossing. The action so panicked his elephants, horses, and men they had to abandon the river crossing until the following day.

�Alexander the Great, Megas Alexandros (July 20, 356 BC - June 10, 323 BC), also known as Alexander III, king of Macedon (336-323 BC), was one of the most successful Ancient Greek military commanders in history. The name 'Alexander' derives from the Greek words "alexo" meaning refuge, defense, protection) and "aner" meaning man).

Before his death, he conquered most of the world known to the ancient Greeks. Alexander is also known in the Zoroastrian Middle Persian work Arda Wiraz Namag as "the accursed Alexander" due to his conquest of the Persian Empire and the destruction of its capital Persepolis.

He is known as Eskandar-e Maqduni (Alexander of Macedonia) in Persian, Al-Iskander Al-Makadoni (Alexander of Macedonia) in Arabic, Alexander Mokdon in Hebrew, and Tre-Qarnayia in Aramaic (the two-horned one, apparently due to an image on coins minted during his rule that seemingly depicted him with the two ram's horns of the Egyptian god Ammon),(Alexander the Great) in Arabic, Sikandar-e-azam Sikandar, his name in Urdu and Hindi, is also a term used as a synonym for "expert" or "extremely skilled".

Following the unification of the multiple city-states of ancient Greece under the rule of his father, Philip II of Macedon (a labour Alexander had to repeat twice because the southern Greeks rebelled after Philip's death), Alexander conquered the Persian Empire, including Anatolia, Syria, Phoenicia, Judea, Gaza, Egypt, Bactria and Mesopotamia and extended the boundaries of his own empire as far as the Punjab. Before his death, Alexander had already made plans to also turn west and conquer Europe. He also wanted to continue his march eastwards in order to find the end of the world, since his boyhood tutor Aristotle told him tales about where the land ends and the Great Outer Sea begins. Alexander integrated foreigners into his army, leading some scholars to credit him with a "policy of fusion." He encouraged marriage between his army and foreigners, and practiced it himself. After twelve years of constant military campaigning, Alexander died, possibly of malaria, West Nile virus, typhoid, viral encephalitis or the consequences of heavy drinking.

His conquests ushered in centuries of Greek settlement and cultural influence over distant areas, a period known as the Hellenistic Age, a combination of Greek and Middle Eastern culture. Alexander himself lived on in the history and myth of both Greek and non-Greek cultures. After his death (and even during his life) his exploits inspired a literary tradition in which he appears as a legendary hero in the tradition of Achilles.

Alexander was born on the 6th day of the ancient Greek month of Hekatombaion, which probably corresponds to 20 July 356 BC, although the exact date is not known, in Pella, the capital of the Ancient Greek Kingdom of Macedon. He was the son of the king of Macedon, Philip II, and his fourth wife, Olympias, the daughter of Neoptolemus I, king of Epirus.Although Philip had seven or eight wives, Olympias was his principal wife for some time, likely a result of giving birth to Alexander.

Several legends surround Alexander's birth and childhood. According to the ancient Greek biographer Plutarch, Olympias, on the eve of the consummation of her marriage to Philip, dreamed that her womb was struck by a thunder bolt, causing a flame that spread "far and wide" before dying away. Some time after the wedding, Philip is said to have seen himself, in a dream, securing his wife's womb with a seal engraved with a lion's image. Plutarch offered a variety of interpretations of these dreams: that Olympias was pregnant before her marriage, indicated by the sealing of her womb; or that Alexander's father was Zeus. Ancient commentators were divided about whether the ambitious Olympias promulgated the story of Alexander's divine parentage, variously claiming that she had told Alexander, or that she dismissed the suggestion as impious.

On the day that Alexander was born, Philip was preparing a siege on the city of Potidea on the peninsula of Chalcidice. That same day, Philip received news that his general Parmenion had defeated the combined Illyrian and Paeonian armies, and that his horses had won at the Olympic Games. It was also said that on this day, the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, burnt down. This led Hegesias of Magnesia to say that it had burnt down because Artemis was away, attending the birth of Alexander. Such legends may have emerged when Alexander was king, and possibly at his own instigation, to show that he was superhuman and destined for greatness from conception.

In his early years, Alexander was raised by a nurse, Lanike, sister of Alexander's future general Cleitus the Black. Later in his childhood, Alexander was tutored by the strict Leonidas, a relative of his mother, and by Philip's general Lysimachus. Alexander was raised in the manner of noble Macedonian youths, learning to read, play the lyre, ride, fight, and hunt.

When Alexander was ten years old, a trader from Thessaly brought Philip a horse, which he offered to sell for thirteen talents. The horse refused to be mounted and Philip ordered it away. Alexander however, detecting the horse's fear of its own shadow, asked to tame the horse, which he eventually managed. Plutarch stated that Philip, overjoyed at this display of courage and ambition, kissed his son tearfully, declaring: "My boy, you must find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions. Macedon is too small for you", and bought the horse for him. Alexander named it Bucephalas, meaning "ox-head". Bucephalas carried Alexander as far as India. When the animal died (due to old age, according to Plutarch, at age thirty), Alexander named a city after him, Bucephala.

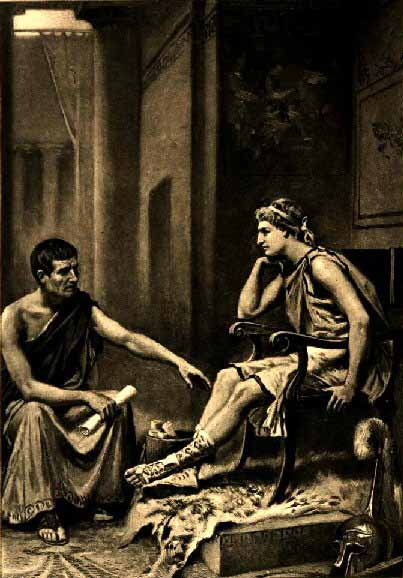

When Alexander was 13, Philip began to search for a tutor, and considered such academics as Isocrates and Speusippus, the latter offering to resign to take up the post. In the end, Philip chose Aristotle and provided the Temple of the Nymphs at Mieza as a classroom. In return for teaching Alexander, Philip agreed to rebuild Aristotle's hometown of Stageira, which Philip had razed, and to repopulate it by buying and freeing the ex-citizens who were slaves, or pardoning those who were in exile.

Mieza was like a boarding school for Alexander and the children of Macedonian nobles, such as Ptolemy, Hephaistion, and Cassander. Many of these students would become his friends and future generals, and are often known as the 'Companions'. Aristotle taught Alexander and his companions about medicine, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, and art. Under Aristotle's tutelage, Alexander developed a passion for the works of Homer, and in particular the Iliad; Aristotle gave him an annotated copy, which Alexander later carried on his campaigns.

At age 16, Alexander's education under Aristotle ended. Philip waged war against Byzantion, leaving Alexander in charge as regent and heir apparent.[9] During Philip's absence, the Thracian Maedi revolted against Macedonia. Alexander responded quickly, driving them from their territory. He colonized it with Greeks, and founded a city named Alexandropolis.

Upon Philip's return, he dispatched Alexander with a small force to subdue revolts in southern Thrace. Campaigning against the Greek city of Perinthus, Alexander is reported to have saved his father's life. Meanwhile, the city of Amphissa began to work lands that were sacred to Apollo near Delphi, a sacrilege that gave Philip the opportunity to further intervene in Greek affairs. Still occupied in Thrace, he ordered Alexander to muster an army for a campaign in Greece. Concerned that other Greek states might intervene, Alexander made it look as though he was preparing to attack Illyria instead. During this turmoil, the Illyrians invaded Macedonia, only to be repelled by Alexander.

Philip and his army joined his son in 338 BC, and they marched south through Thermopylae, taking it after stubborn resistance from its Theban garrison. They went on to occupy the city of Elatea, only a few days' march from both Athens and Thebes. The Athenians, led by Demosthenes, voted to seek alliance with Thebes against Macedonia. Both Athens and Philip sent embassies to win Thebes' favor, but Athens won the contest. Philip marched on Amphissa (ostensibly acting on the request of the Amphictyonic League), capturing the mercenaries sent there by Demosthenes and accepting the city's surrender. Philip then returned to Elatea, sending a final offer of peace to Athens and Thebes, who both rejected it.

As Philip marched south, his opponents blocked him near Chaeronea, Boeotia. During the ensuing Battle of Chaeronea, Philip commanded the right wing and Alexander the left, accompanied by a group of Philip's trusted generals. According to the ancient sources, the two sides fought bitterly for some time. Philip deliberately commanded his troops to retreat, counting on the untested Athenian hoplites to follow, thus breaking their line. Alexander was the first to break the Theban lines, followed by Philip's generals. Having damaged the enemy's cohesion, Philip ordered his troops to press forward and quickly routed them. With the Athenians lost, the Thebans were surrounded. Left to fight alone, they were defeated.

After the victory at Chaeronea, Philip and Alexander marched unopposed into the Peloponnese, welcomed by all cities; however, when they reached Sparta, they were refused, but did not resort to war. At Corinth, Philip established a "Hellenic Alliance" (modeled on the old anti-Persian alliance of the Greco-Persian Wars), which included most Greek city-states except Sparta. Philip was then named Hegemon (often translated as "Supreme Commander") of this league (known by modern scholars as the League of Corinth), and announced his plans to attack the Persian Empire.

In 336 BC, while at Aegae attending the wedding of his daughter Cleopatra to Olympias's brother, Alexander I of Epirus, Philip was assassinated by the captain of his bodyguards, Pausanias. As Pausanias tried to escape, he tripped over a vine and was killed by his pursuers, including two of Alexander's companions, Perdiccas and Leonnatus. Alexander was proclaimed king by the nobles and army at the age of 20.

Alexander began his reign by eliminating potential rivals to the throne. He had his cousin, the former Amyntas IV, executed.He also had two Macedonian princes from the region of Lyncestis killed, but spared a third, Alexander Lyncestes. Olympias had Cleopatra Eurydice and Europa, her daughter by Philip, burned alive. When Alexander learned about this, he was furious. Alexander also ordered the murder of Attalus, who was in command of the advance guard of the army in Asia Minor and Cleopatra's uncle.

Attalus was at that time corresponding with Demosthenes, regarding the possibility of defecting to Athens. Attalus also had severely insulted Alexander, and following Cleopatra's murder, Alexander may have considered him too dangerous to leave alive. Alexander spared Arrhidaeus, who was by all accounts mentally disabled, possibly as a result of poisoning by Olympias.

News of Philip's death roused many states into revolt, including Thebes, Athens, Thessaly, and the Thracian tribes north of Macedon. When news of the revolts reached Alexander, he responded quickly. Though advised to use diplomacy, Alexander mustered the Macedonian cavalry of 3,000 and rode south towards Thessaly. He found the Thessalian army occupying the pass between Mount Olympus and Mount Ossa, and ordered his men to ride over Mount Ossa. When the Thessalians awoke the next day, they found Alexander in their rear and promptly surrendered, adding their cavalry to Alexander's force. He then continued south towards the Peloponnese.

Alexander stopped at Thermopylae, where he was recognized as the leader of the Amphictyonic League before heading south to Corinth. Athens sued for peace and Alexander pardoned the rebels. The famous encounter between Alexander and Diogenes the Cynic occurred during Alexander's stay in Corinth. When Alexander asked Diogenes what he could do for him, the philosopher disdainfully asked Alexander to stand a little to the side, as he was blocking the sunlight. This reply apparently delighted Alexander, who is reported to have said "But verily, if I were not Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes." At Corinth Alexander took the title of Hegemon ("leader"), and like Philip, was appointed commander for the coming war against Persia. He also received news of a Thracian uprising.

Map of Alexander's empire and his route

Before crossing to Asia, Alexander wanted to safeguard his northern borders. In the spring of 335 BC, he advanced to suppress several revolts. Starting from Amphipolis, he traveled east into the country of the "Independent Thracians"; and at Mount Haemus, the Macedonian army attacked and defeated the Thracian forces manning the heights. The Macedonians marched into the country of the Triballi, and defeated their army near the Lyginus river (a tributary of the Danube). Alexander then marched for three days to the Danube, encountering the Getae tribe on the opposite shore. Crossing the river at night, he surprised them and forced their army to retreat after the first cavalry skirmish.

News then reached Alexander that Cleitus, King of Illyria, and King Glaukias of the Taulanti were in open revolt against his authority. Marching west into Illyria, Alexander defeated each in turn, forcing the two rulers to flee with their troops. With these victories, he secured his northern frontier.

While Alexander campaigned north, the Thebans and Athenians rebelled once again. Alexander immediately headed south. While the other cities again hesitated, Thebes decided to fight. The Theban resistance was ineffective, and Alexander razed the city and divided its territory between the other Boeotian cities. The end of Thebes cowed Athens, leaving all of Greece temporarily at peace. Alexander then set out on his Asian campaign, leaving Antipater as regent.

Secrets of Alexander the Great mosaic revealed after 1st-of-its-kind analysis Live Science - January 16, 2025

There are around 2 million pieces that make up the Alexander the Great mosaic, but where did they come from? An iconic Alexander the Great mosaic found at Pompeii got its roughly 2 million pieces from quarries that extended far beyond Alexander's ancient kingdom, a new study finds. While Alexander's empire stretched from the Balkans to modern-day Pakistan, these bits of stone and mineral, or tesserae, came from quarries across Europe - including in Italy and the Iberian Peninsula - as well as from Tunisia.

Alexander's army had crossed the Hellespont with about 40,000 soldiers, which primarily consisted of Macedonians, Greeks, Thracians, Paionians, and Illyrians. After an initial victory against Persian forces at the Battle of Granicus, Alexander accepted the surrender of the Persian provincial capital and treasury of Sardis and proceeded down the Ionian coast. At Halicarnassus, Alexander successfully waged the first of many sieges, eventually forcing his opponents, the mercenary captain Memnon of Rhodes and the Persian satrap of Caria, Orontobates, to withdraw by sea.

Alexander left Caria in the hands of Ada, who was ruler of Caria before being deposed by her brother Pixodarus. From Halicarnassus, Alexander proceeded into mountainous Lycia and the Pamphylian plain, asserting control over all coastal cities and denying them to his enemy. From Pamphylia onward, the coast held no major ports and so Alexander moved inland.

At Termessus, Alexander humbled but did not storm the Pisidian city. At the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordium, Alexander "undid" the tangled Gordian knot, a feat said to await the future "king of Asia." According to the most vivid story, Alexander proclaimed that it did not matter how the knot was undone, and he hacked it apart with his sword. Another version claims that he did not use the sword, but actually figured out how to undo the knot.

From Babylon, Alexander went to Susa, one of the Achaemenid capitals, and captured its treasury. Sending the bulk of his army to Persepolis, the Persian capital, by the Royal Road, Alexander stormed and captured the Persian Gates (in the modern Zagros Mountains), then sprinted for Persepolis before its treasury could be looted. Alexander allowed the League forces to loot Persepolis. A fire broke out in the eastern palace of Xerxes and spread it to the rest of the city. It was not known if it was a drunken accident or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Athenian Acropolis during the Second Persian War.

He then set off in pursuit of Darius, who was kidnapped, and then murdered by followers of Bessus, his Bactrian satrap and kinsman. Bessus then declared himself Darius' successor as Artaxerxes V and retreated into Central Asia to launch a guerrilla campaign against Alexander. With the death of Darius, Alexander declared the war of vengeance over, and released his Greek and other allies from service in the League campaign (although he allowed those that wished to re-enlist as mercenaries in his imperial army).His three-year campaign against first Bessus and then the satrap of Sogdiana, Spitamenes, took him through Media, Parthia, Aria, Drangiana, Arachosia, Bactria, and Scythia. In the process, he captured and refounded Herat and Maracanda. Moreover, he founded a series of new cities, all called Alexandria, including modern Kandahar in Afghanistan, and Alexandria Eschate ("The Furthest") in modern Tajikistan. In the end, both were betrayed by their men, Bessus in 329 BC and Spitamenes the year after.

During this time, Alexander adopted some elements of Persian dress and customs at his court, notably the custom of proskynesis, a symbolic kissing of the hand that Persians paid to their social superiors, but a practice of which the Greeks disapproved. The Greeks regarded the gesture as the preserve of deities and believed that Alexander meant to deify himself by requiring it. This cost him much in the sympathies of many of his countrymen. Here, too, a plot against his life was revealed, and his companion Philotas was executed for treason for failing to bring the plot to his attention.

Parmenion, Philotas' father, who was at the head of an army at Ecbatana, was assassinated by command of Alexander, who feared that Parmenion might attempt to avenge his son. Several other trials for treason followed, and many Macedonians were executed. Later on, in a drunken quarrel at Maracanda, he also killed the man who had saved his life at Granicus, Clitus the Black. Later in the Central Asian campaign, a second plot against his life, this one by his own pages, was revealed, and his official historian, Callisthenes of Olynthus (who had fallen out of favor with the king by leading the opposition to his attempt to introduce proskynesis), was implicated on what many historians regard as trumped-up charges. However, the evidence is strong that Callisthenes, the teacher of the pages, must have been the one who persuaded them to assassinate the king.

With the death of Spitamenes and his marriage to Roxana (Roshanak in Bactrian) to cement his relations with his new Central Asian satrapies, in 326 BC Alexander was finally free to turn his attention to India. King Ambhi, ruler of Taxila, surrendered the city to Alexander. Many people had fled to a high fortress called Aornos. Alexander took Aornos by storm. Alexander fought an epic battle against Porus, a ruler of a region in the Punjab in the Battle of Hydaspes in (326 BC). After attaining victory, Alexander made an alliance with Porus and appointed him as satrap of his own kingdom. Alexander continued on to conquer all the headwaters of the Indus River.

East of Porus' kingdom, near the Ganges River, was the powerful empire of Magadha ruled by the Nanda dynasty. Exhausted by years of campaigning, his army mutinied at the Hyphasis (modern Beas), refusing to march further east. Alexander, after the meeting with his officer, Coenus, was convinced that it was better to return. Alexander was forced to turn south, conquering his way down the Indus to the Indian Ocean. He sent much of his army to Carmania (modern southern Iran) with his general Craterus, and commissioned a fleet to explore the Persian Gulf shore under his admiral Nearchus, while he led the rest of his forces back to Persia by the southern route through the Gedrosia (present day Makran in southern Pakistan).

Discovering that many of his satraps and military governors had misbehaved in his absence, Alexander executed a number of them as examples on his way to Susa. As a gesture of thanks, he paid off the debts of his soldiers, and announced that he would send those over-aged and disabled veterans back to Macedonia under Craterus, but his troops misunderstood his intention and mutinied at the town of Opis, refusing to be sent away and bitterly criticizing his adoption of Persian customs and dress and the introduction of Persian officers and soldiers into Macedonian units. Alexander executed the ringleaders of the mutiny, but forgave the rank and file. In an attempt to craft a lasting harmony between his Macedonian and Persian subjects, he held a mass marriage of his senior officers to Persian and other noblewomen at Opis, but few of those marriages seem to have lasted much beyond a year.

His attempts to merge Persian culture with his Greek soldiers also included training a regiment of Persian boys in the ways of Macedonians. It is not certain that Alexander adopted the Persian royal title of shahanshah ("great king" or "king of kings"). However, most historians believe that he did.Alexander let it be known that he intended to launch a campaign against the tribes of Arabia. After they were subjugated, it was assumed that Alexander would turn westwards and attack Carthage and Italy.

After traveling to Ecbatana to retrieve the bulk of the Persian treasure, his closest friend and probable lover Hephaestion died of an illness. Alexander was distraught and on his return to Babylon, he fell ill and died.

On the afternoon of June 10 - 11, 323 BC, Alexander died of a mysterious illness in the palace of Nebuchadrezzar II of Babylon. He was only 33 years old. Various theories have been proposed for the cause of his death which include poisoning by the sons of Antipater, sickness that followed a drinking party or a relapse of the malaria he had contracted in 336 BC.

What is certain is that on May 29, Alexander participated in a banquet organized by his friend Medius of Larissa. After some heavy drinking, immediately or after a bath, he was forced to bed badly ill. While the troops started rumouring, more and more anxious, on June 9, the generals decided to let the soldiers see their king alive one last time. They were admitted to his presence one at a time, while the king, too ill to speak, confined himself to move his hand. The day after, Alexander was dead.

The poisoning theory derives from the story held in antiquity by Justin and Curtius. The original story stated that Cassander, son of Antipater, viceroy of Greece, brought the poison to Alexander in Babylon in a mule's hoof, and that Alexander's royal cupbearer, Iollas, brother of Cassander, administered it. All had powerful motivations for seeing Alexander gone, and all were none the worse for it after his death.

However, many other ancient historians, like Plutarch and Arrian, maintained that Alexander was not poisoned, but died of natural causes. The strongest argument against the poison theory entails the fact that twelve days had passed between the start of his illness and his death. Alexander's death may not have been caused by poisoning being that in the ancient world, such long-acting poisons were not available. Various theories have been advanced stating that the king may have died from other illnesses other than malaria, including the West Nile virus.

These theories often cite the fact that Alexander's health had fallen to dangerously low levels after years of overdrinking and suffering several appalling wounds (including one in India that nearly claimed his life), and that it was only a matter of time before one sickness or another finally killed him.Neither story is conclusive. Alexander's death has been reinterpreted many times over the centuries, and each generation offers a new take on it. What is certain is that Alexander died of a high fever in early June 10 or 11 of 323 BC.

On his death bed, his marshals asked him to whom he bequeathed his kingdom. Since Alexander had only one heir, it was a question of vital importance. He answered famously, "the strongest." Before dying, his final words were "I foresee a great funeral contest over me." Alexander's 'funeral games', where his marshals fought it out over control of his empire, lasted for nearly forty years.

Alexander's death has been surrounded by as much controversy as many of the events of his life. Before long, accusations of foul play were being thrown about by his generals at one another, making it incredibly hard for a modern historian to sort out the propaganda and the half-truths from the actual events. No contemporary source can be fully trusted because of the incredible level of self-serving recording, and as a result what truly happened to Alexander the Great may never be known.

Alexander's body was placed in a gold anthropid sarcophagus, which was in turn placed in a second gold casket and covered with a purple robe. Alexander's coffin was placed, together with his armor, in a gold carriage which had a vaulted roof supported by an Ionic peristyle. The decoration of the carriage was very rich and is described in great detail by Diodoros.According to legend, Alexander was preserved in a clay vessel full of honey (which acts as a preservative) and interred in a glass coffin.

According to Aelian (Varia Historia 12.64), Ptolemy stole the body and brought it to Alexandria, where it was on display until Late Antiquity. It was here that Ptolemy IX, one of the last successors of Ptolemy I, replaced Alexander's sarcophagus with a glass one, and melted the original down in order to strike emergency gold issues of his coinage. Its current whereabouts are unknown.

The so-called "Alexander Sarcophagus," discovered near Sidon and now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, is now generally thought to be that of Abdylonymus, whom Hephaestion appointed as the king of Sidon by Alexander's order. The sarcophagus depicts Alexander and his companions hunting and in battle with the Persians.

Modern opinion on Alexander has run the gamut from the idea that he believed he was on a divinely-inspired mission to unite the human race, to the view that he was a megalomaniac bent on world domination. Such views tend to be anachronistic, however, and the sources allow for a variety of interpretations. Much about Alexander's personality and aims remains enigmatic.

Alexander is remembered as a legendary hero in Europe and much of both Southwest Asia and Central Asia, where he is known as Iskander or Iskandar Zulkarnain.

To Zoroastrians, on the other hand, he is remembered as the destroyer of their first great empire and as the leveller of Persepolis. Ancient sources are generally written with an agenda of either glorifying or denigrating the man, making it difficult to evaluate his actual character.

Most refer to a growing instability and megalomania in the years following Gaugamela, but it has been suggested that this simply reflects the Greek stereotype of an orientalising king. The murder of his friend Clitus, which Alexander deeply and immediately regretted, is often cited as a sign of his paranoia, as is his execution of Philotas and his general Parmenion for failure to pass along details of a plot against him. However, this may have been more prudence rather than paranoia.

Modern Alexandrists continue to debate these same issues, among others, in modern times. One unresolved topic involves whether Alexander was actually attempting to better the world by his conquests, or whether his purpose was primarily to rule the world.

Partially in response to the ubiquity of positive portrayals of Alexander, an alternate character is sometimes presented which emphasizes some of Alexander's negative aspects. Some proponents of this view cite the destructions of Thebes, Tyre, Persepolis, and Gaza as examples of atrocities, and argue that Alexander preferred to fight rather than negotiate. It is further claimed, in response to the view that Alexander was generally tolerant of the cultures of those whom he conquered, that his attempts at cultural fusion were severely practical and that he never actually admired Persian art or culture. To this way of thinking, Alexander was, first and foremost, a general rather than a statesman.

Alexander's character also suffers from the interpretation of historians who themselves are subject to the bias and idealisms of their own time. Good examples are W. W. Tarn, who wrote during the late 19th century and early 20th century, and who saw Alexander in an extremely good light, and Peter Green, who wrote after World War II and for whom Alexander did little that was not inherently selfish or ambition-driven. Tarn wrote in an age where world conquest and warrior-heroes were acceptable, even encouraged, whereas Green wrote with the backdrop of the Holocaust and nuclear weapons. As a result, Alexander's character is skewed depending on which way the historian's own culture is, and further muddles the debate of who he truly was.

One undeniable characteristic of Alexander is that he was extremely pious and devout, and began every day with prayers and sacrifices. From his boyhood he believed "one should not be parsimonious with the gods."

According to one story, the philosopher Anaxarchus checked the vainglory of Alexander, when he aspired to the honors of divinity, by pointing to Alexander's wound, saying, "See the blood of a mortal, not the ichor of a god." In another version, Alexander himself pointed out the difference in response to a sycophantic soldier. A strong oral tradition, although not attested in any extant primary source, lists Alexander as having epilepsy, known to the Greeks as the Sacred Disease and thought to be a mark of divine favor.

Alexander had a legendary horse named Bucephalus (meaning "ox-headed"), supposedly descended from the Mares of Diomedes. Alexander himself, while still a young boy, tamed this horse after experienced horse-trainers failed to do so.

Alexander's greatest emotional attachment is generally considered to have been to his companion, cavalry commander (chiliarchos) and probable lover, Hephaestion. They had most likely been best friends since childhood for Hephaestion too received his education at the court of Alexander's father. Hephaestion makes his appearance in history at the point when Alexander reaches Troy. There the two friends made sacrifices at the shrines of the two heroes Achilles and Patroclus, Alexander honoring Achilles, and Hephaestion honoring Patroclus. As Aelian in his Varia Historia (12.7) claims, "He thus intimated that he was the object of Alexander's love, as Patroclus was of Achilles."

Many discussed his ambiguous sexuality. Curtius reports that, "He scorned feminine sensual pleasures to such an extent that his mother was anxious lest he be unable to beget offspring." To whet his appetite for the fairer sex, King Philip and Olympias brought in a high-priced Thessalian courtesan named Callixena.

Later in life, Alexander married several princesses of former Persian territories, Roxana of Bactria, Statira, daughter of Darius III, and Parysatis, daughter of Ochus. He fathered one child, Alexander IV of Macedon, born by Roxana shortly after his death in 323 BC, and he also had in 327 BC a son, (Heracles), by his concubine Barsine, the daughter of satrap Artabazus of Phrygia.

Curtius maintains that Alexander also took as a lover "Bagoas, a eunuch exceptional in beauty and in the very flower of boyhood, with whom Darius was intimate and with whom Alexander would later be intimate," (VI.5.23). Bagoas is the only one who is actually named as the eromenos — the beloved — of Alexander.

The word is not used even for Hephaestion. Their relationship seems to have been well known among the troops, as Plutarch recounts an episode (also mentioned by Dicaearchus) during some festivities on the way back from India) in which his men clamor for him to openly kiss the young man: "Bagoas [...] sat down close by him, which so pleased the Macedonians, that they made loud acclamations for him to kiss Bagoas, and never stopped clapping their hands and shouting till Alexander put his arms round him and kissed him."

At this point in time, the troops present were all survivors of the crossing of the desert. Bagoas must have endeared himself to them by his courage and fortitude during that harrowing episode. Whatever Alexander's relationship with Bagoas, it was no impediment to relations with his queen: six months after Alexander's death Roxana gave birth to his son and heir, Alexander IV.

Besides Bagoas, Curtius mentions yet another lover of Alexander, Euxenippus, "whose youthful grace filled him with enthusiasm" (VII.9.19).

The suggestion that Alexander was homosexual or bisexual remains highly controversial and excites passions in some quarters. People of various national, ethnic and cultural origins regard him as a national hero.

They argue that historical accounts describing Alexander's relations with Hephaestion and Bagoas as sexual were written centuries after the fact, and thus it can never be established what the 'real' relationship between Alexander and his male companions were. Others argue that the same can be said about all our information regarding Alexander.

Such debates, however, are considered anachronistic by scholars of the period, who point out that the concept of homosexuality did not exist in Greco-Roman antiquity. Sexual attraction between males was seen as a normal and universal part of human nature since it was believed that men were attracted to beauty, an attribute of the young, regardless of gender.

If Alexander's love life was transgressive, it was not for his love of beautiful youths but for his involvement with a man his own age, in a time when the standard model of male love was pederastic. Alexander The Great Wikipedi