Menpehtyre Ramesses I (traditional English: Ramesses or Ramses) was the founding Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt's 19th dynasty. The dates for his short reign are not completely known but the time-line of late 1292-1290 BC is frequently cited as well as 1295-1294 BC. While Ramesses I was the founder of the 19th Dynasty, in reality his brief reign marked the transition between the reign of Horemheb who had stabilized Egypt in the late 18th dynasty and the rule of the powerful Pharaohs of this dynasty, in particular his son Seti I and grandson Ramesses II, who would bring Egypt up to new heights of imperial power.

Originally called Pa-ra-mes-su, Ramesses I was of non-royal birth, being born into a noble military family from the Nile delta region, perhaps near the former Hyksos capital of Avaris, or from Tanis. He was a son of a troop commander called Seti. His uncle Khaemwaset, an army officer married Tamwadjesy, the matron of the Harem of Amun, who was a relative of Huy, the Viceroy of Kush, an important state post. This shows the high status of Ramesses' family. Ramesses I found favor with Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the tumultuous Eighteenth dynasty, who appointed the former as his Vizier. Ramesses also served as the High Priest of Amun as such, he would have played an important role in the restoration of the old religion following the Amarna heresy of a generation earlier, under Akhenaten.

Horemheb himself had been a nobleman from outside the immediate royal family, who rose through the ranks of the Egyptian army to serve as the royal advisor to Tutankhamun and Ay and, ultimately, Pharaoh. Since Horemheb was childless, he ultimately chose Ramesses to be his heir in the final years of his reign presumably because Ramesses I was both an able administrator and had a son (Seti I) and a grandson (the future Ramesses II) to succeed him and thus avoid any succession difficulties.

Upon his accession, Ramesses assumed a prenomen, or royal name, which is written in Egyptian hieroglyphs to the right. When transliterated, the name is mn-phty-r, which is usually interpreted as Menpehtyre, meaning "Established by the strength of Ra". However, he is better known by his nomen, or personal name. This is transliterated as r'-ms-sw, and is usually realised as Ramessu or Ramesses, meaning 'Ra bore him'. Already an old man when he was crowned, Ramesses appointed his son, the later pharaoh Seti I, to serve as the Crown Prince and chosen successor. Seti was charged with undertaking several military operations during this time - in particular, an attempt to recoup some of Egypt's lost possessions in Syria. Ramesses appears to have taken charge of domestic matters: most memorably, he completed the second pylon at Karnak Temple, begun under Horemheb.

Ramesses I enjoyed a very brief reign, as evidenced by the general paucity of contemporary monuments mentioning him: the king had little time to build any major buildings in his reign and was hurriedly buried in a small and hastily finished tomb.

The Egyptian priest Manetho assigns him a reign of 16 months, but this pharaoh certainly ruled Egypt for a minimum of 17 months based on his highest known date which is a Year 2 II Peret day 20 (Louvre C57) stela which ordered the provision of new endowments of food and priests for the temple of Ptah within the Egyptian fortress of Buhen.

Jurgen von Beckerath observes that Ramesses I died just 5 months late - in June 1290 BC - since his son Seti I succeeded to power on III Shemu day 24. Ramesses I's only known action was to order the provision of endowments for the aforementioned Nubian temple at Buhen and "the construction of a chapel and a temple (which was to be finished by his son) at Abydos.

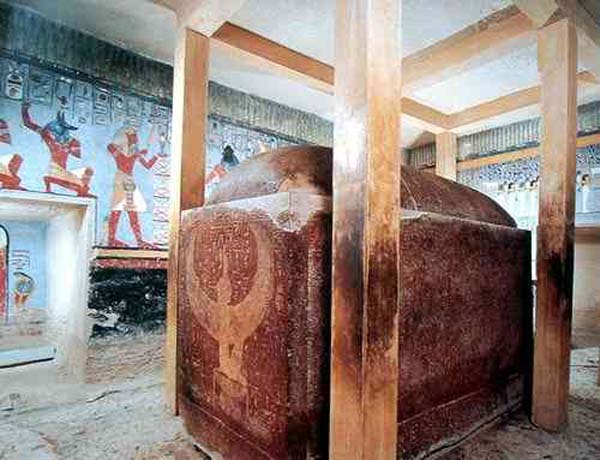

The aged Ramesses was buried in the Valley of the Kings. His tomb, discovered by Giovanni Belzoni in 1817 and designated KV16, is small in size and gives the impression of having been completed with haste. Joyce Tyldesley states that Ramesses I's tomb consisted of a single corridor and one unfinished room whose walls, after a hurried coat of plaster, were painted to show the king with his gods, with Osiris allowed a prominent position. The red granite sarcophagus too was painted rather than carved with inscriptions which, due to their hasty preparation, included a number of unfortunate errors."

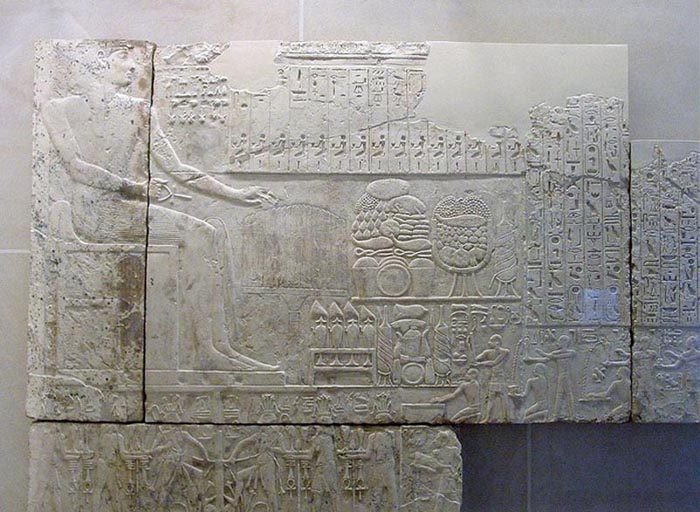

Seti I, his son, and successor, later built a small chapel with fine reliefs in memory of his deceased father Ramesses I at Abydos. In 1911, John Pierpont Morgan donated several exquisite reliefs from this chapel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The tomb of Ramesses I, founder of the great lineage of Ramessid rulers, is one of the smallest in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb (KV 16) was discovered on or before October 11, 1817 by Giovanni Battista Belzoni just before his discovery of the much more significant tomb of Seti I. It is located in a small lateral valley perpendicular to the main Valley of the Kings Wadi. While small, the tomb has wall paintings of excellent workmanship. Having proceeded through a passage thirty-two feet long, and eight feed wide, I descended a staircase of twenty-eight feet, and reached a tolerably large and well-painted room - seventeen feet long, and twenty-one wide.

The ceiling was in good preservation, but not in the best style. There is a sarcophagus of granite, with two mummies in it, and in a corner a statue standing erect, six feet six inches high, and beautifully cut out of sycamore-wood: it is nearly perfect except the nose. There are a number of little images of wood, well carved, representing symbolical figures. Some had a lion's head, others a fox's, others a monkey's. One had a land-tortoise instead of a head. There is a calf with the head of a hippopotamus. At each side of this chamber is a smaller one, eight feet wide, and seven feet long; and at the end of it another chamber, ten feet long by seven wide.

The sarcophagus was covered with hieroglyphics merely painted, or outlined: it faced south-east by east. The tomb is rectilinear in structure with only a single corridor, unlike most the rest of the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. The corridor is located between two descending sets of stairways, and is the shortest of any royal tomb in the valley. The second set of stars opens directly into the burial chamber.

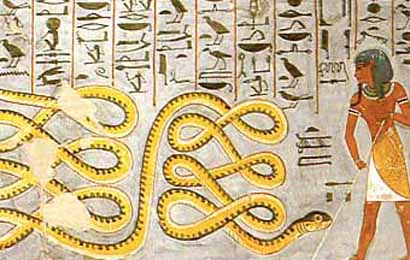

A large, granite sarcophagus dominates the burial chamber. The paintings on the sarcophagus are not finished, and were hurriedly done. The decorations of the tomb, like those of Horemheb, are related to the Book of Gates and all have blue backgrounds.

While the decorations are well done, their are no reliefs. In the burial chamber, Ramesses, presenting offerings to Atum-Re-Khepri, is led into the presence of Osiris by Horus, Atum and Neith. There is also an unusual depiction of the Pharaoh in a ceremony of jubilation between a hawk and jackal-headed figure representing the spirits of the cities of Nekhen and Pe. The burial chamber and left annex are the only rooms in the tomb that are decorated, and it is very likely that the same craftsman who worked on Horemheb's tomb also worked on this one.

According to current theory, his mummy was stolen by the Abu-Rassul family of grave robbers and brought to North America around 1860 by Dr. James Douglas. It was then placed in the Niagara Museum and Daredevil Hall of Fame in Ontario, Canada. Ramesses I remained there, his identity unknown, next to other curiosities and so-called freaks of nature for more than 130 years. When the owner of the museum decided to sell his property, Canadian businessman William Jamieson purchased the contents of the museum.

In 1999, Jamieson sold the Egyptian artifacts in the collection, including the various mummies, to the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia for US $2 million. His identity cannot be conclusively determined, but is persuasively deduced from CT scans, X-rays, skull measurements and radio-carbon dating tests by researchers at the University, as well as aesthetic interpretations of family resemblance. Moreover, the mummy's arms were found crossed high across his chest which was a position reserved solely for Egyptian royalty until 600 BC. His mummy was returned to Egypt on October 24, 2003 with full official honors and is on display at the Luxor Museum.