The Bannock, Mono, Timbisha and Kawaiisu people, who also speak Numic languages and live in adjacent areas are sometimes referred to as Paiute. The Bannock speak a dialect of Northern Paiute, while the other three people speak separate Numic languages, with Mono being more closely related to Northern Paiute, Kawaiisu being more closely related to Ute-Southern Paiute, and Timbisha being more closely related to Shoshone.

The origin of the word Paiute is unclear. Some anthropologists have interpreted it as "Water Ute" or "True Ute." The Northern Paiute call themselves Numa (sometimes written Numu) ; the Southern Paiute call themselves Nuwuvi. Both terms mean "the people." The Northern Paiute are sometimes referred to as Paviotso. Early Spanish explorers called the Southern Paiute "Payuchi" (they did not make contact with the Northern Paiute). Early Euro-American settlers often called both groups of Paiute "Diggers" (presumably because of their practice of digging for roots), although that term is now considered derogatory.

The origin of the word Paiute is unclear - some anthropologists have interpreted it as Water Ute or True Ute. The Northern Paiute call themselves Numa (sometimes written as Numu). The Southern Paiute call themselves Nuwuvi. Both terms mean the people.

Early Spanish explorers called the Southern Paiute Payuchi. They did not make contact with the Northen Paiute. Early Euro-American settlers often called both groups of Paiute Diggers - presumably due to their practice of digging for roots, although that term is now considered derogatory. The Northern Paiute are sometimes referred to as Paviotso.

The Northern Paiute traditionally lived in the Great Basin in eastern California, western Nevada, and southeast Oregon. Their pre-contact lifestyle was well adapted to the harsh desert environment in which they lived. Each tribe or band occupied a specific territory, generally centered on a lake or wetland which supplied fish and water-fowl.

The language of the Northern Paiute is a Shoshonean dialect.

Rabbits and Pronghorn were taken from surrounding areas in communal drives, which often involved neighboring bands. Individuals and families appear to have moved freely between bands. Pinyon nuts gathered in the mountains in the fall provided critical winter food. Grass seeds and roots were also important parts of their diet.

The Northern Paiutes migrated frequently and wide because they relied on game and certain plants. They hunting much of the year, for deer and rabbits.

The name of each band came from a characteristic food source. For example, the people at Pyramid Lake were known as the Cui Ui Ticutta - meaning "Cui-ui eaters". People of the Lovelock area were known as the Koop Ticutta - meaning "ground-squirrel" eaters. People of the Carson Sink were known as the Toi Ticutta meaning "tule eaters".

Relations among the Northern Paiute bands and their Shoshone neighbors were generally peaceful. In fact the distinction between the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone is not sharp.

Sustained contact between the Northern Paiute and Euro-Americans came in the early 1840s, although the first contact may have been in the 1820s. Although they had already started using horses, their culture was otherwise largely unaffected by European influences at that point. As Euro-American settlement of the area progressed, several violent incidents occurred including the Pyramid Lake War of 1860 and the Bannock War of 1878.

These incidents took the general pattern of a settler stealing from, raping or murdering a Paiute, after which a group of Paiutes retaliated, followed by a group of settlers or the US Army counter-retaliating.

Many Paiutes died from introduced diseases such as small pox.

After 1840, with the rush of European prospectors and farmers and the consequent despoiling of their already meagre supply of food plants, the Northern Paiute acquired guns and horses and fought at intervals with the whites until 1874, when the last Paiute lands were appropriated by the U.S. government.

The first reservation established for the Northern Paiute was the Malheur Reservation in Oregon. The federal government's intention was to concentrate the Northern Paiute there, however its strategy didn't work. Due to the distance of that reservation from the traditional areas of most of the bands, and due to the poor conditions on that reservation, many Northern Paiute refused to go there and those that did soon left. Instead they clung to the traditional lifestyle as long as possible, and when environmental degradation made that impossible they sought jobs on white farms, ranches or cities and established small Indian colonies, where they were joined by many Shoshone and, in the Reno area, Washoe people.

Later, large reservations were created at Pyramid Lake and Duck Valley, however by that time the pattern of small de facto reservations near cities or farm districts often with mixed Northern Paiute and Shoshone populations had been established.

Starting in the early 1900s the federal government began granting land to these colonies, and under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 these colonies gained recognition as independent tribes.

Southern Paiute people migrated to the plateaus of Colorado River basin, Mojave Desert in northern Arizona, southeast California, southern Nevada, and southern Utah, around 1100-1200 A.D.

The Utah Paiutes were terminated in 1954 and regained Federal Recognition in 1980. A band of Southern Paiutes at Willow Springs and Navajo Mountain, south of the Grand Canyon, reside inside the Navajo Indian Reservation. They, too were recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1980.

Southern Paiute people spoke a dialect of the Numic language. Those who spoke Ute, occupied southern Utah, northwestern Arizona, southern Nevada, and southeastern California, the last group being known as the

Chemehuevi.

First European contact with the Southern Paiutes was in 1776 when Father Dominguez and Escalante chanced upon them on their failed attempt to find an overland route to the missions of California.

In 1851, Mormon settlers strategically occupied Paiute water sources creating a dependency relationship.

Although encroached upon and directed into reservations by the U.S. government in the 19th century, the Southern Paiute had comparatively little friction with whites. Many stayed scattered in the territories, working on the ranches of whites or remaining on the fringes of white settlements.

Southern Paiute communities today are located at Las Vegas, Pahrump, and Moapa, Nevada; Cedar City, Kanosh, Koosharem, Shivwits, and Indian Peaks,Utah; at Kaibab and Willow Springs, Arizona; and at Death Valley and Chemehuevi on the Colorado River in California. Some would include the 29 Palms Reservation in Riverside County California.

Southern Paiute were traditionally food collectors who subsisted on seed, pine nuts, and small game, although many Southern Paiute planted small gardens as well as hunting for food.

The Southern Paiute would eat the meat of their game as well as the crushed bones of the animal. They did not waste anything. In addition to meat, the Paiute ate plant life.

The women of the Southern Paiute would cultivate a number of crops using water sources that were available. They planted corn, squash, pumpkins, muskmelons, beans and sunflowers. They grew wheat during the late 18th century. Gathering various seeds and leafy greens to supplement their diet was very important. The Paiute women did a lot of basket weaving with their children.

They occupied temporary brush shelters, wore little or no clothing except rabbitskin blankets, and made a variety of baskets for gathering and cooking food.

Families were affiliated through intermarriage, but there were no formal bands or territorial organizations, except in the more fertile areas such as the Owens River valley in California. Little of the old customs survive, except for shamanism.

Known as the messiah to his followers, Wovoka was the Paiute mystic whose religious pronouncements spread the Ghost Dance among many tribes across the American West.

Wovoka (1856-1932), also known as Jack Wilson, was a Northern Paiute religious leader and founder of the Ghost Dance movement. Wovoka means "wood cutter" in the Northern Paiute language.

Wovoka was born in the Smith Valley area southeast of Carson City, Nevada, around the year 1856. Wovoka's father may have been Numu-Taibo ("white person"), a religious leader whose teachings were similar to those of Wovoka. Regardless, Wovoka clearly had some training as a shaman.

Wovoka's father died around the year 1870, and he was taken in by David Wilson, who was a rancher in the Yerington, Nevada area. Wovoka worked on the Wilson ranch, and used the name Jack Wilson in his dealings with whites. David Wilson was a devout Christian, and Wovoka learned English, Christian theology, and bible stories while living with him.

In his early adulthood, Wovoka gained a reputation as a powerful shaman. He was adept at magic tricks. One trick he often performed was being shot with a shotgun, which may have been similar to the bullet catch trick. Reports of this trick may have convinced the Lakota that their "ghost shirts" could stop bullets. Wovoka is also reported to have performed a levitation trick.

In early 1889 Wovoka proclaimed that he had a prophetic vision during the solar eclipse on January 1 of that year. Wovoka vision entailed the resurrection of the Paiute dead and the removal of whites and their works from North America.

To bring this vision to pass, Wovoka taught that they must live righteously and perform a round dance, known as the "Ghost Dance".

At around age thirty, Wovoka began to weave together various cultural strains into the Ghost Dance religion. He had a rich tradition of religious mysticism upon which to draw.

Around 1870, a northern Paiute named Tavibo had prophezied that while all whites would be swallowed up by the Earth, all dead Indians would emerge to enjoy a world free of their conquerors.

He urged his followers to dance in circles, already a tradition in the Great Basin area, while singing religious songs. Tavibo's movement spread to parts of Nevada, California, and Oregon.

Whether or not Tavibo was Wovoka's father, as many at the time assumed, in the late 1880's Wovoka began to make similar prophecies.

His pronouncements heralded the dawning of a new age, in which whites would vanish, leaving Indians to live in a land of material abundance, spiritual renewal and immortal life. Like many millenarian visions, Wovoka's prophecies stressed the link between righteous behavior and imminent salvation. Salvation was not to be passively awaited but welcomed by a regime of ritual dancing and upright moral conduct.

Despite the later association of the Ghost Dance with the Wounded Knee Massacre and unrest on the Lakota reservations, Wovoka charged his followers:

While the Ghost Dance is sometimes seen today as an expression of Indian militancy and the desire to preserve traditional ways, Wovoka's pronouncements ironically bore the heavy mark of popular Christianity.

Wovoka's invocation of a "Supreme Being," immortality, pacifism and explicit mentions of Jesus (often referred to with such phrases as "the messiah who came once to live on Earth with the white man but was killed by them") all speak of an infusion of Christian beliefs into Paiute mysticism.

The Ghost Dance spread throughout much of the West, especially among the more recently defeated Indians of the Great Plains. Local bands would adopt the core of the message to their own circumstances, writing their their own songs and dancing their own dances.

In 1889 the Lakota sent a delegation to visit Wovoka. This group brought the Ghost Dance back to their reservations, where believers made sacred shirts -- said to be bullet-proof -- especially for the Dance.

The slaughter of Big Foot's band at Wounded Knee Creek in 1890 was cruel proof that whites were not about to simply vanish, that the millennium was not at hand. Wovoka quickly lost his notoriety and lived as Jack Wilson until sometime in 1932.

He left the Ghost Dance as evidence of a growing pan-Indian identity which drew upon elements of both white and Indian traditions.

The Promise of the Ghost Dance

Ghost Dance

By the morning of January 1, 1889, Wovoka was clearly a man torn apart by the conflicts of his past. His father's failure to be taken seriously as a prophet, the suffering of the Native peoples and his own religious concepts (both tribal and Christian) weighed heavily on him. On that day, Wovoka claimed to have dreamed a vision of a new and glorious world for the Native peoples. But was it really a new world?

In his dream, Wovoka conversed with God, who promised a new world set aside for the Native peoples. The wildlife of the region which was nearly depleted by white settlers (buffalo, elk, deer) would be replenished. The white settlers would vanish en mass and the Native dead would be resurrected and reunited with their living ancestors. Suffering, starvation, pain and disease would be wiped away forever. From a theological viewpoint and the safety of hindsight, however, one can detect prophecies which were not tribal in origin.

Even the most casual churchgoer would recognize the visions of the Book of Revelation in Wovoka's prophecies. Yet Wovoka's audience - the Paiute people and, later, other tribal nations - did not recognize it simply because Christianity did not take root among the Native peoples. White missionaries, for all of their efforts, did not put their faith into the hearts of most Native peoples. Wovoka, obviously recognizing this, refashioned the Revelation warning to his world.

He claimed the Native peoples would receive God's favor since it was the white man who rejected Christ. And unlike the New Testament, which was vague concerning the time and place of God's new world, Wovoka spelled out the immediacy of what he said. "Jesus is now upon the Earth," he stated. But again, there is historic contradiction here- Wovoka is quoted as saying he was Christ and he wasn't Christ. It would seem that either he excelled at playing to different audiences or was damned to being preserved by faulty historians.

Wovoka added this new world for Native peoples would come, but only if a ritualistic dance was practiced. In his initial preaching, he instructed his audiences to dance five days and four nights, then bathe in a river and go home. Wovoka promised to send a good spirit to his followers, who were to return in three months, at which time he would promise "such rain as I have never given you before."

The ritualistic dance, which became known as Ghost Dance, clearly appealed to the Native peoples who were baffled by the pew-bound protocol of Christian faiths. Unlike the calls of his father Tavibo, Wovoka found an audience eager to follow his teachings.

Ghost Dance spread to different nations throughout the west with a speed and ferocity unrivaled by any religious frenzy of the day. This turn of events was all the more remarkable for three reasons: the geographic and language barriers among the various nations, the lack of access to media or technology for spreading this news, and the fact that Wovoka never left the Paiute land.

Instead, members of other nations came to Nevada to learn from him. Why Wovoka did not travel could be attributed to either a fear of unknown territories, a lack of funds to accommodate travel or even the possibility of enemies.

In the summer of 1890, among those who visited Wovoka were two members of the Lakota reservation at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, named Kicking Bear and Short Bull.

They became enraptured by Wovoka's faith and even stated that Wovoka levitated through the air above them. Kicking Bear and Short Bull brought Ghost Dance back to Pine Ridge, but in a very different form which lead to totally unexpected results.

Wovoka's faith was based on non-violence with whites. In fact, he even urged his followers not to tell the whites what they were doing. But as interpreted by Kicking Bear and Short Bull, Ghost Dance took on a militaristic aspect. Special garments known as Ghost Shirts were to be worn to deflect bullets fired by white soldiers or settlers. Government agents were permitted to witness the Ghost Dance ceremony and were told what it meant. Kicking Bear and Short Bull added the Indian Messiah would appear to the Lakota in the Spring of 1891.

Ghost Dance came to the Lakota with a fury. All activity at the Pine Ridge Reservation was put aside and the Native peoples adopted this faith with a mania. Government agents and white settlers were terrified by this sudden and (to them) bizarre turn of events. Newspapers spread stories of savage Indians in wild pagan practices.

Tensions became overpowering in this region as the Lakota people gave all their waking hours to Ghost Dance. (One government agent, Daniel F. Royer, tried to distract the Lakota by bringing his nephew to Pine Ridge to introduce baseball. It did not work. A missionary named Catherine Weldon offered to debate Kicking Bear on religion, but nothing came of it.)

Blame for Ghost Dance was placed on two people. Wovoka was traced as the father of the Ghost Dance and was interviewed by James Mooney, an ethnologist and anthropologist with the Smithsonian Institute. Wovoka passed a message to Mooney that he would control any militaristic uprising among the Native peoples in return for financial and food compensation from Washington.

The offer was ignored. And blame was also put on Sitting Bull, the chief medicine man of the Lakota people. Ironically, Sitting Bull was apathetic to Ghost Dance and only allowed its introduction at Pine Ridge with great caution. His initial qualms were realized: government agents considered Sitting Bull responsible solely due to his leadership role among the Lakota. Tribal police were dispatched to arrest him, but his apprehension resulted in conflict when several Lakota fought to protect him. Sitting Bull was killed in the crossfire on December 15, 1890.

Fourteen days after Sitting Bull's fatal shooting, the U.S. Army sought to relocate and disarm the Lakota people, who failed to stop their Ghost Dance. On the frozen plains at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation, government troops opened fire on the overwhelmingly unarmed Lakota people, killing 290 in a matter of minutes. Thirty-three soldiers died, most from friendly fire; 20 Medals of Honor were presented to surviving soldiers.

As news of Wounded Knee spread throughout the Native nations, Ghost Dance died quickly. Wovoka's prophecies were hollow; the land would not be returned from the white man through divine intervention. With the suddenness of its birth, Ghost Dance disappeared.

Wovoka himself virtually vanished into obscurity. In his later years, he exhibited himself at sideshows in county fairs and worked as an extra in silent movie Westerns. (The one surviving photograph of Wovoka was taken on the set of a film.) By the time of his death on September 20, 1932, he was virtually forgotten by both white and Native peoples. It would not be until the 1970s and the birth of Native American activism that the story of the Ghost Dance was told again— even if its father's life was reduced to footnote status.

The tragedy of Wovoka is a legacy of pain and suffering among the very people he wanted to save. The songs of the Ghost Dance are silent today and the dream of Wovoka vanished in the harsh light of reality. The Christian principles which he laced into his theology were brutally ignored by the soldiers and settlers who held allegiance to Christ and yet destroyed the Native way of life with a brutality unknown in the Gospel teachings.

- James Mooney, The Ghost-dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890

Sarah was born into a family of great leaders with both her father and her grandfather having been Chiefs of this Nevada Nation. It was her grandfather who led Capt.John Fremont and his group across the Great Basin to safety in California. This willingness to befriend the whites was never forgotten, and word of these deeds quickly spread across California.

When Sarah's father decided to take his family for a visit to the San Joaquin Valley in California, his news was received with great fears for Sarah was terrified of the whites. However, her fears disappeared as the Winnemucca party was assisted along the way by kind and generous whites.

Sarah was fascinated by these strange people and their strange ways, and set out to learn all she could about them. While on her 3 week visit in California, she quickly learned the basics of English.

Upon her return to Nevada, she had the opportunity to live for a year with the Ormsby family where she mastered the language. Sarah became 1 of 2 Paiutes in the entire state to read, write and speak English. In addition, she mastered Spanish, and 3 other Native dialects.

In her thirst for knowledge, she enrolled in St.Mary's Convent, but was forced to leave after only one month because of white anger at a Native being allowed into the school.

Great tensions arose between the Paiute and the growing river of whites pouring into Nevada. As a result of the Paiute War, the Paiute Reservation was established at Pyramid Lake, outside of what is now Reno.

Even this did not halt the unwarranted aggression against the Natives who were killed at random and their homes destroyed by raiding soldiers. In an effort to stop the bloodshed, Sara became an interpreter and spokesperson between the Paiutes and whites but, in retaliation against her, her mother, sister and brother were murdered by whites. Impressed by her command of English, Sarah was hired by the Army to serve as official interpreter between the U.S. and several Native tribes of the area. She was barely in her teens.

In her official capacity with the Army, Sarah was able to watch politics at work from the inside out. It did not take her long to understand that the persecution of the Paiutes lay at the feet of the government Indian Agents. Despite orders from Washington, and even an Act of Congress, the violence against the Paiutes continued. Sarah's hatred of the government Indian Agents is legendary, and became a cause that dominated her life. She traveled to the West Coast, meeting with official after official to present her case for justice. She was ignored.

When the neighboring Bannocks of Idaho rose up against white encroachment, the Northern Paiute joined their war. Sarah distinguished herself as a mighty warrior in battle. Sickened at the bloodshed, Sarah once again took on the role of interpreter and peacemaker, traveled into the heart of Bannock country, and convinced her father, Chief Winnemucca, to return home to Nevada with his warriors.

During the Bannock War, the reservation Paiutes had been forcibly taken from their land and moved to a reservation in the State of Washington. There, they continued to suffer at the hands of still more unscrupulous Indian Agents.

For Sarah, this was the final blow, and she took her cause to Washington, D.C. She spoke before Congress, and in other major cities on the East Coast where she could get an audience. In Boston, she became the protegee of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody and Mary Mann, wife of influential Horace Mann. With their encouragement and help, Sarah wrote her autobiography, "Life Among The Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims", as a way to spread the word of the injustice and corruption among government agents to even more people.

She was a master political activist and lobbyist in the classical sense.

During her long absences, the Paiute had begun to escape their confinement in Washington State, and were gradually returning to their homeland.

Sarah had kicked up such a storm across the country that her people were more or less left alone and were not forcibly removed again. She returned to Nevada where she opened a series of Native schools across the state.

However, a lifetime of crusading had taken its toll on Sarah's physical and emotional state.

She gave up her fight, and moved to a sister's home in Monida, Montana where she died of tuberculosis at age 47.

Sarah Winnemucca was called "The Princess" by whites; "Mother" by the Paiutes, and "The most famous Indian woman on the Pacific Coast" by historians.

The City of Winnemucca, Nevada carries her family name, and Sarah's memory.

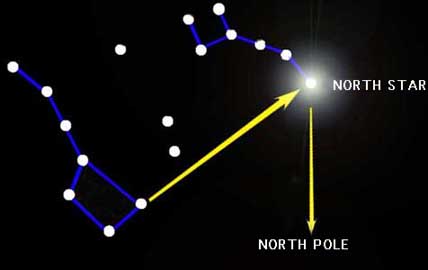

Long ago, when the world was young, the People of the Sky were so restless and traveled so much that they made trails in the heavens. Now, if we watch the sky all through the night, we can see which way they go.

But one star does not travel. That is the North Star. He cannot travel. He cannot move. When he was on the earth long, long ago, he was known as Na-gah, the mountain sheep, the son of Shinoh. He was brave, daring, sure-footed, and courageous. His father was so proud of him and loved him so much that he put large earrings on the sides of his head and made him look dignified, important, and commanding.

Every day, Na-gah was climbing, climbing, climbing. He hunted for the roughest and the highest mountains, climbed them, lived among them, and was happy.

Once in the very long ago, he found a very high peak. Its sides were steep and smooth, and its sharp peak reached up into the clouds.

Na-gah looked up and said, "I wonder what is up there. I will climb to the very highest point."

Around and around the mountain he traveled, looking for a trail. But he could find no trail. There was nothing but sheer cliffs all the way around. This was the first mountain Na-gah had ever seen that he could not climb.

He wondered and wondered what he should do. He felt sure that his father would feel ashamed of him if he knew that there was a mountain that his son could not climb.

Na-gah determined that he would find a way up to its top. His father would be proud to see him standing on the top of such a peak.

Again and again he walked around the mountain, stopping now and then to peer up the steep cliff, hoping to see a crevice on which he could find footing.

Again and again, he went up as far as he could, but always had to turn around and come down.

At last he found a big crack in a rock that went down, not up. Down he went into it and soon found a hole that turned upward. His heart was made glad. Up and up he climbed.

Soon it became so dark that he could not see, and the cave was full of loose rocks that slipped under his feet and rolled down. Soon he heard a big, fearsome noise coming up through the shaft at the same time the rolling rocks were dashed to pieces at the bottom.

In the darkness he slipped often and skinned his knees. His courage and determination began to fail. He had never before seen a place so dark and dangerous. He was afraid, and he was also very tired.

"I will go back and look again for a better place to climb," he said to himself. "I am not afraid out on the open cliffs, but this dark hole fills me with fear. I'm scared! I want to get out of here!"

But when Na-gah turned to go down, he found that the rolling rocks had closed the cave below him. He could not get down. He saw only one thing now that he could do: He must go on climbing until he came out somewhere.

After a long climb, he saw a little light, and he knew that he was coming out of the hole.

"Now I am happy," he said aloud. "I am glad that I really came up through that dark hole."

Looking around him, he became almost breathless, for he found that he was on the top of a very high peak! There was scarcely room for him to turn around, and looking down from this height made him dizzy. He saw great cliffs below him, in every direction, and saw only a small place in which he could move. Nowhere on the outside could he get down, and the cave was closed on the inside..,

"Here I must stay until I die," he said. "But I have climbed my mountain! I have climbed my mountain at last!

He ate a little grass and drank a little water that he found in the holes in the rocks. Then he felt better. He was higher than any mountain he could see and he could look down on the Earth, far below him.

About this time, his father was out walking over the sky. He looked everywhere for his son, but could not find him.

He called loudly, "Na-gah! Na-gah!"

And his son answered him from the top of the highest cliffs.

When Shinoh saw him there, he felt sorrowful, to himself, "My brave son can never come down. Always he must stay on the top of the highest mountain. He can travel and climb no more. I will not let my brave son die. I will turn him into a star, and he can stand there and shine where everyone can see him. He shall be a guide mark for all the living things on the Earth or in the sky."

And so Na-gah became a star that every living thing can see. It is the only star that will always be found at the same place.

Always he stands still. Directions are set by him. Travelers, looking up at him, can always find their way.

He does not move around as the other stars do, and so he is called "the Fixed Star." And because he is in the true north all the time, our people call him Qui-am-i Wintook Poot-see. These words mean the North Star.

Besides Na-gah, other mountain sheep are in the sky. They are called "Big Dipper" and "Little Dipper." They too have found the great mountain and have been challenged by it. They have seen Na-gah standing on its top, and they want to go on up to him.

Shinoh, the father of North Star, turned them into stars, and you may see them in the sky at the foot of the big mountain. Always they are traveling. They go around and around the mountain, seeking the trail that leads upward to Na-gah, who stands on the top. He is still the North Star.

The Paiute Indians in the desert hills have this story of the bright star that may be seen low down in the eastern sky about sunrise of summer mornings -- the star we know as Sirius in the constellation Canis Major, commonly called the "dog-star."

A long time ago, one of their young men attempted to run down a deer. All the village watched them as they ran across the desert, away over the rim of the world into the sky. There they were changed, the deer and the runner, to a star. Since that time the Indians say that the best deer-hunting is to be had when the "deer-star" is in the sky; and this is really true.

In the bluish light of dawn

Rose up for the red deer hunting,

And what should a hunter do

Who has never an arrow feathered,

Nor a bow strung taut and true?

The women laughed from the doorways,

the maidens mocked at the spring;

For thus to be slack at the hunting is ever a shameful thing.

The old men nodded and muttered,

but the youth spoke up with a frown:

"If I have no gear for the hunting,

I will run the red deer down."

He is off by the hills of the morning,

By the dim, untrodden ways;

In the clean, wet, windy marshes

He has startled the deer agraze;

And a buck of the branching antlers

Streams out from the fleeing herd,

And the youth is apt to the running

As the tongue to the spoken word.

They have gone by the broken ridges,

by mesa and hill and swale,

Nor once did the red deer falter,

nor the feet of the runner fail;

So lightly they trod on the lupines

that scarce were the flower-stalks bent,

And over the tops of the dusky sage

the wind of their running went.

They have gone by the painted desert,

Where the dawn mists lie uncurled,

And over the purple barrows

On the outer rim of the world.

The people shout from the village,

And the sun gets up to spy

The royal deer and the runner,

Clear shining in the sky.

And ever the hunter watches for the rising of that star

When he comes by the summer mountains

where the haunts of the red deer are,

When he comes by the morning meadows

where the young of the red deer hide;

He fares him forth to the hunting

while the deer and the runner bide.