Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 BC to 1450 BC. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civilization. It evolved into Linear B, which was used by the Mycenaeans to write an early form of Greek. It was discovered by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in 1900. No texts in Linear A have yet been deciphered. Evans named the script "Linear" because its characters consisted simply of lines inscribed in clay, in contrast to the more pictographic characters in Cretan hieroglyphs that were used during the same period.

Linear A belongs to a group of scripts that evolved independently of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian systems. During the second millennium BC, there were four major branches: Linear A, Linear B, Cypro-Minoan, and Cretan hieroglyphic.

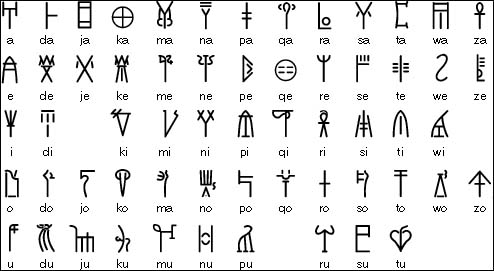

In the 1950s, Linear B was deciphered and found to have an underlying language of Mycenaean Greek. Linear A shares many glyphs and alloglyphs with Linear B, and the syllabic glyphs are thought to notate similar syllabic values, but none of the proposed readings lead to a language that scholars can read.

Linear A consists of over 300 signs including regional variants and hapax legomena. Among these, a core group of 90 occur with some frequency throughout the script's geographic and chronological extent.

The complex sign in the top row is formed out of the two on the bottom row. As a logosyllabic writing system, Linear A includes signs which stand for syllables as well as others standing for words or concepts. Linear A's signs could be combined via ligature to form complex signs. Complex signs usually behave as ideograms and most are hapax legomena, occurring only once in the surviving corpus. Thus, Linear A signs are divided into four categories: Read more ...

Linear A: One Of Europe's First Writing Systems Remains Undeciphered To This Day IFL Science - November 20, 2024

Sometimes regarded as the first true European civilization, the Minoan culture rose to prominence on the Greek island of Crete between 3100 to 1100 BCE, during the Bronze Age. It spread and gained influence across parts of the Eastern Mediterranean before completely crumbling amid the late Bronze Age Collapse. The society was a hotbed of creativity and human ingenuity. Minoan Crete is the setting for many ancient Greek legends, most notably the Labyrinth and the Minotaur, indicating it had a clear influence on Greek mythology and culture. It was also a pioneer of grand architecture, the most famous being the Palace of Knossos, as well as artworks and ornate objects of beauty.

Among these relics, archaeologists have found extensive evidence of a writing system composed of around 75 symbols each representing a syllable (as opposed to a letter) or a specific concept (known as an ideogram). Based on the context of the inscriptions, it’s safe to assume that Linear A was used in at least two contexts: the sublime writings of religion and the hum-drum accounting of traded goods.

Linear B is the name given to a writing system discovered by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941) at Knossos on Crete in 1900. Evans believed he had discovered the palace of King Minos, together with the Minotaur's labyrinth. He was also convinced that the language represented by Linear B was not Greek but an unrelated language which he called 'Minoan'.

In 1939, a large number of clay tablets inscribed with Linear B writing were found at Pylos on the Greek mainland, much to the surprise of Evans, who thought Linear B was used only on Crete.

Evans spent the rest of his life trying to decipher Linear B, with only limited success. He realized that three different writing systems were used in ancient Crete: a 'hieroglyphic' script, Linear A, and Linear B. The hieroglyphic script appears only on seal stones and has yet to be deciphered. Linear A, also undeciphered, is thought to have evolved from the hieroglyphic script and was used until the 15th Century BC. After the Greeks conquered Knossos, Linear B developed, probably from Linear A, although the relationship between the two scripts is unclear.

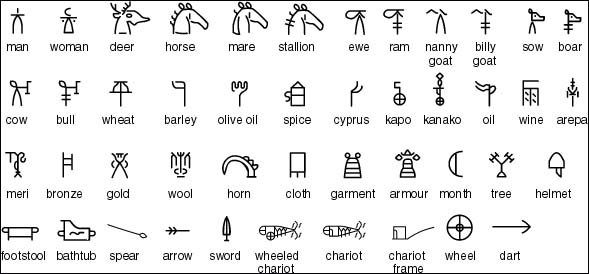

Evans figured out that short lines in Linear B texts were word dividers. He also deciphered the counting system and a number of pictograms, which led him to believe that the script was mainly pictographic. Evans also discovered a number of parallels between the Cypriot script, which had been deciphered, and Linear B. This indicated that the language represented by Linear B was an ancient form of Greek, but he wasn't prepared to accept this, being convinced that Linear B was used to write Minoan, a language unrelated to Greek.

Micheal Ventris (1922-56) was the person who eventually deciphered Linear B in 1953. His interest was sparked in 1936 on a school trip to an exhibition about the Minoan world organised by Arthur Evans. For the next 17 years, Ventris struggled to understand Linear B. At first, he was sceptical that the language of Linear B was Greek, even though many of the deciphered words resembled a form of Ancient Greek. Later, with the help of John Chadwick, an expert on early Greek, he showed beyond reasonable doubt the Linear B did indeed represent Greek.

These logograms stand for whole words and mainly represent items that were traded. As Linear B was used mainly for recording transactions, this is not surprising. Some of the logograms resemble the things they represent, so could be called pictograms. Not all the logograms have been deciphered. Read more ...