A dying god, also known as a dying-and-rising or resurrection deity, is a god who dies and is resurrected or reborn, in either a literal or symbolic sense. Male examples include the ancient Near Eastern and Greek deities Baal, Melqart, Adonis, Eshmun, Attis, Tammuz, Asclepius, Orpheus, as well as Krishna, Ra, Osiris, Jesus, Zalmoxis, Dionysus, and Odin. Female examples are Inanna, also known as Ishtar, whose cult dates to 4000 BCE, and Persephone, the central figure of the Eleusinian Mysteries, whose cult may date to 1700 BCE as the unnamed goddess worshiped in Crete.

The term "dying god" is associated with the works of James Frazer, Jane Ellen Harrison, and their fellow Cambridge Ritualists. In their seminal works The Golden Bough and Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, Frazer and Harrison argued that all myths are echoes of rituals, and that all rituals have as their primordial purpose the manipulation of natural phenomena by means of sympathetic magic. Consequently, the rape and return of Persephone, the rending and repair of Osiris, the travails and triumph of Baldr, derive from primitive rites intended to renew the fertility of withered land and crops.

The category 'life-death-rebirth deity' also known as a 'dying-and-rising goddess' is a convenient means of classifying the many divinities in world mythology or religion who are born, suffer death or an eclipse or other death-like experience, pass a phase in the underworld among the dead, and are subsequently reborn, in either a literal or symbolic sense. Such deities might include Osiris, Adonis, Jesus, and Mithras. Female deities who passed into the kingdom of death and returned include Inanna and Persephone, the central figure of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Historically, this category has been most strongly associated with two different approaches to the study of religion. The first, which might be labelled the "naturalist" approach, seeks to explain such myths in terms of parallels with natural processes. The second, which might be labelled the "internal" approach, seeks to explain such myths in terms of individual spiritual transformation.

Of the two major life-death-and-resurrection approaches to hermeneutics, the naturalistic explication has more support in ancient sources. These rituals were closely linked to the cycle of seasons, as when Athenian women planted "gardens of Adonis" in pots and then, when the young green growth withered in the heat of the summer, wept for the dead young god. Already in Antiquity, the rationalizing approach of Aristotle could be elaborated to a rigidly naturalistic interpretation of myth origins as explanations of natural seasonal phenomena. Such a reductionist interpretation was apparently epitomized by Euhemerus (late 4th century BC), giving the term "euhemerist". Rational Stoic Romans like Cicero and Seneca, who saw the official and civil nature of ritual as paramount, were prepared to explain the myths and festivals of Attis, Adonis and Persephone in terms of natural phenomena. The abduction and return of Persephone, Cicero argued, was symbolic of the planting and growth of crops.

In the late eighteenth century, the naturalist interpretation took on renewed vigor, as freethinkers like Richard Payne Knight sought to explain all religious phenomena in terms of solar activity. Thus the tribulations of Jesus and Osiris were both taken to represent the course of the sun through the day, night, and dawn (Godwin, 1994).

The naturalist hypothesis reached a further apogee in the works of James Frazer and Jane Ellen Harrison, and their fellow Cambridge Ritualists. In their seminal works The Golden Bough and Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, Frazer and Harrison argued that all myths are only echoes of rituals, and that all rituals have as their primordial purpose the manipulation of natural phenomena by means of sympathetic magic. The rape and return of Persephone, the rending and repair of Osiris, the travails and triumph of Baldur would therefore all be rooted in primitive rites to renew the fertility of withered land and crops.

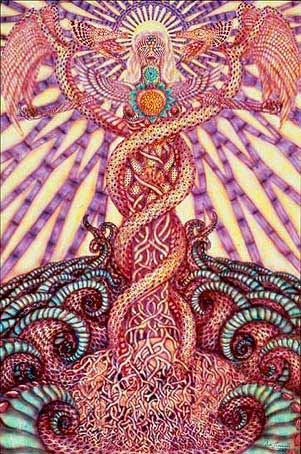

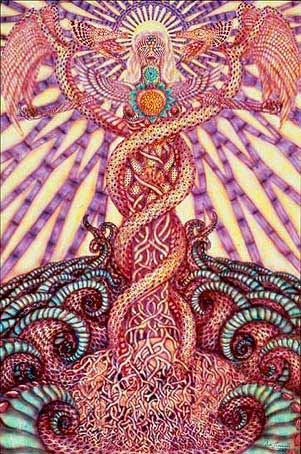

By the Victorian era, the solar-phallic ideas of Payne Knight along with the less risqu work of scholars like Max Mller had taken strange turns as they made their way into popular discourse. Groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn were using scholarly parallels between Christ, Osiris and other putative solar dying-and-rising gods to build up elaborate systems of mysticism and theosophy.

By the twentieth century, this spiritualized turn to the universal-dying-god hypothesis had made its way into the sunlit uplands of academic discourse. From his studies of alchemy and other spiritual systems, the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung argued that archetypal processes such as death and resurrection were part of the transpersonal symbolism of the Collective Unconscious, and could be utilized in the task of psychological integration.

Jung's line of argumentation has been followed, with modifications, by scholars like Karl Kerenyi and Joseph Campbell.

The chief criticism that has been brought against the universal life-death-resurrection deity category is that it is reductionist: in seeking to fit disparate myths into a single box, critics would contend, the hypothesis obscures distinctions that really matter. Furthermore, since death and resurrection are more central to Christianity than most other faiths, it risks making Christianity the standard by which all religion is judged. For extended arguments in this vein, see e.g. Burkert, 1987 and Detienne, 1994.

Detienne, for example, has studied the ritual growing and withering of herb gardens at the Athenian Adonia festival. He argues that rather than being a stand-in for crops in general, these herbs (and the herb-god Adonis) were part of a complex of associations in the Greek mind that centered around spices. These associations included seduction, trickery, gourmandise, and the anxieties of childbirth. From this point of view, Adonis's death is only one datum among the many that must be used to analyze the festival, the myth and the god. On the other hand a god like Osiris, whose functions relate to crops and the dead rather than spices and love, would call for a very different interpretation, despite the common theme of having died. Such, then, are the objections to the dying-and-rising-god hermeneutic.

The putative existence of a universal dying-and-rising god motif, and the particular existence of mystery religions concerned with dying and rising gods around the Mediterranean Sea (e.g. Osiris, Dionysus, Attis), has led some observers to speculate that Jesus, rather than being a historical person, was in fact a syncretizing development of this archetype. Others point out that Jesus may well have been historical, with only the story of his resurrection added under the influence of the Hellenistic mystery religions. C. S. Lewis after his conversion to Christianity understood the resurrection of Jesus as belonging in this category of myths, with the additional property of having actually happened in history: "If God chooses to be mythopoeic - and is not the sky itself a myth - shall we refuse to be mythopathic?" (Lewis, "Myth became fact"). For more on this question, see Historicity of Jesus.