Flag of the northern Cheyenne

Flag of the northern Cheyenne

The Cheyenne are a Native American nation of the Great Plains, closely allied with the Arapaho and loosely allied with the Lakota (Sioux). They are one of the most famous and prominent Plains tribes.

The Cheyenne nation is composed of two united tribes, the Sotaae'o and the Tsitsistas, which translates to "Like Hearted People".

The Cheyenne nation comprised 10 bands, spread all over the Great Plains, from southern Colorado to the Black Hills in South Dakota.

In the early 1800s the tribe split into two factions: the southern band staying near the Platte Rivers and the northern band living near the Black Hills near the Lakota tribes.

The Cheyenne of Montana and Oklahoma both speak the Cheyenne language, with only a handful of vocabulary items different between the two locations. The Cheyenne language is a tonal language and is part of the larger Algonquian language group.

In 1851, the first Cheyenne 'territory' was established in northern Colorado. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 granted this territory.

Today this former territory includes the cities of Fort Collins, Denver and Colorado Springs. Not long after 1851, the Cheyenne had lost this land due to the influx of settlers due to the gold rush.

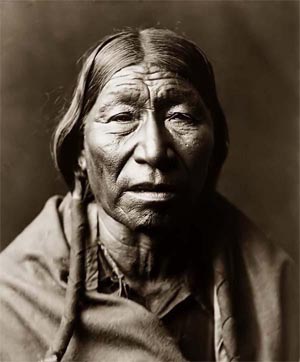

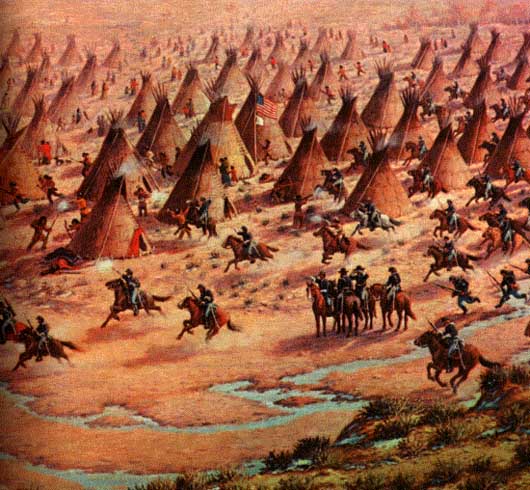

In the Indian Wars, the Cheyenne were the victims of the Sand Creek Massacre in which the Colorado Militia killed 600 Cheyenne. In the early morning on November 27, 1868 the Battle of Washita River started when United States Army Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led the 7th U.S. Cavalry in an attack on a band of peaceful Cheyenne legally living on reservation land with Chief Black Kettle. 103 Cheyenne were killed, mostly women and children.

The Indian Wars were a series of conflicts between the United States and Native American peoples ("Indians") of North America. The wars, which ranged from colonial times to the Wounded Knee massacre and "closing" of the American frontier in 1890, collectively resulted in the conquest of American Indian peoples and their decimation, assimilation, or forced relocation to Indian reservations.

The term Indian Wars is misleading because it groups American Indians under a single heading. American Indians were (and remain) a diverse category of peoples with discrete histories; throughout the wars, they were not a single people any more than Europeans were. Living in societies organized in a variety of ways (the terms tribe or nation are not always accurate), American Indians usually made decisions about war and peace at the local level, though they sometimes fought as part of complex formal alliances such as the Iroquois Confederation, or in temporary confederacies inspired by charismatic leaders such as Tecumseh.

There are other problems with the term Indian Wars. It creates a category which has traditionally been used to relegate the long story of American Indian warfare to a minor footnote in U.S. history. The term also tends to obscure American Indian involvement in other wars. For example, American Indians fought extensively in the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, two wars which had massive consequences for Native Americans, yet these conflicts have not traditionally been labeled as Indian Wars.

To see the Indian wars as a racial war between Indians and European-Americans ("whites") overlooks the complex historical reality of the struggle. Indians and whites often fought alongside each other; Indians often fought against Indians. For example, although the Battle of Horseshoe Bend is often described as an "American victory" over the Creek Indians, the victors were a combined force of Cherokees, Creeks, and Tennessee militia led by Andrew Jackson. From a broad perspective, the Indian wars were about the conquest of Native American peoples by the United States; up close it was rarely quite as simple as that.

Citing figures from a 1894 estimate by the United States Census Bureau, one scholar has noted that the more than 40 Indian wars from 1775 to 1890 reportedly claimed the lives of some 45,000 Indians and 19,000 whites. This rough estimate includes women and children, since noncombatants were often killed in frontier warfare.

The Sand Creek Massacre refers to an infamous incident in the Indian Wars of the United States that occurred on November 29, 1864 when Colorado Militia troops in the Colorado Territory massacred an undefended village of Cheyenne and Arapaho encamped on the territory's eastern plains. The attack was initially reported in the press as a victory against a bravely-fought defense by the Cheyenne. Within weeks, however, eyewitnesses came forward offering conflicting testimony, leading to a military investigation and two Congressional investigations into the events.

Starting the 1850s, the gold rush in the Rocky Mountains (then part of the western Kansas Territory) had brought a flood of white settlers into the mountains and the surrounding foothills. The sudden immigration came into conflict with the Cheyenne and the Arapaho who inhabited the area, eventually leading to the Colorado War in 1864. The violence between the Native Americans and the miners spread, prompting territorial governor John Evans to send Colonel John Chivington to quiet the Indians.

After a few skirmishes and a decisive warpath on the part of the Indians, the Cheyennes and Arapahos were ready for peace and camped near Fort Lyon on the eastern plains.

Both of the tribes had signed a treaty with the United States just three years before in which they ceded their lands to the United States and agreed to move to the Indian reservation to the south of Sand Creek, demarcated by a line to be run due north from a point on the northern boundary of New Mexico, fifteen miles west of Purgatory River, and extending to the Sandy Fork of the Arkansas River.

Chief Black Kettle, a chief of a group of mostly Southern Cheyennes - and some Arapahoes, some 550 in number, reported to Fort Lyon in an effort to declare peace. After having done so, he and his band camped out at nearby Sand Creek, less than 40 miles north. Having heard the Indians had surrendered, Chivington and his 700 troops of the First Colorado Cavalry, Third Colorado Cavalry and a company of First New Mexico Volunteers marched to their campsite in order to obtain an easy victory.

On the morning of November 29, 1864, the army shot down people as if they were buffalo, killing as many as 150, or about one-quarter of the entire group. The dead were mainly old men, women and children and the cavalry lost only 9 or 10 killed and three dozen wounded.

One man, Silas Soule, a Massachusetts abolitionist, refused to follow Colonel Chivington's orders. He did not allow his cavalry company to fire into the crowd.After the massacre, some tribal members decided to join the Dog Soldiers, a group of Cheyenne who decided there could be no successful negotiations with the white men and were waging war against them.

The nation was shocked by the brutality of the massacre and the army decided to investigate Chivington's role. Silas Soule was extremely willing to testify against him. After he testified, Soule was murdered by Charles W. Squires. It is believed that Chivington had a hand in this murder.

The Northern Cheyenne also participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which took place on June 25, 1876. The Cheyenne, along with the Lakota and a small band of Arapaho, annihilated George Armstrong Custer and his contingent.

It is estimated that population of the encampment of the Cheyenne, Lakota and Arapaho along the Little Bighorn River was around 10,000; which would make it one of the largest gathering of Native Americans in North America in pre-reservation times.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, also called Custer's Last Stand, was an engagement between a Lakota-Northern Cheyenne combined force and the 7th Cavalry of the United States Army, June 25- June 26, 1876 near the Little Bighorn River in the eastern Montana Territory. The battle was the most famous incident in the Indian Wars and was a remarkable victory for the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne. The U.S. cavalry detachment commanded by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer was killed to the last man, but overall, the majority of U.S. soldiers survived the fight.

The U.S. forces were sent to attack the Indians based on Indian Inspector's E.C. Watkins report (issued on November 9, 1875) that stated that hundreds of Lakota and Northern Cheyenne associated with Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were hostile to the United States. U.S. interest in Indian lands (including the gold-rich Black Hills) also played an important role.

As the larger wing of the troops under Gen. Alfred Terry, Custer's force arrived at an overlook 14 miles east of the Little Bighorn River in what is now the state of Montana, on the night of June 24. The rest of the column was marching toward the mouth of the Little Bighorn, to provide a blocking action by the 26th.

The presence of what was judged a very large encampment of Indians was reported to the general by his Crow Indian scouts. Despite this warning, on June 25, Custer divided his regiment into four commands and moved forward to attack the encamped Indians, who were expected to flee at the first sign of attack. The first battalion to attack was commanded by Major Marcus Reno and preceded by about a dozen Arikara and friendly Sioux scouts.

His orders, given by Custer without accurate knowledge of the village's size, location, or propensity to stand and fight, were to pursue the Indians and "bring them to battle." However, Custer did promise to "support...[Reno] with the whole outfit." Reno's force crossed the Little Bighorn at the mouth of what is today called Reno Creek, and immediately realized that the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne were present "in force and ...not running away."

Sending a message to Custer, but hearing nothing in return, Reno launched its offensive northward. He stopped a few hundred yards short of the village, however, and dismounted, unwilling to attack the enormous village with his roughly 125 men. In about 20 minutes of long distance firing, he had taken only one casualty, but the odds against him had become more obvious, and Custer had not reinforced him.

Reno ordered a retreat to nearby woods, and then made a disorderly retreat to the river and up to the top of the bluffs on the other side, suffering heavy casualties along the way. Reno was at the head of this movement and called it a charge; no bugle calls were heard, and a number of men were left in the woods. The river crossing was unguarded, and a number of men died there.

At the top of the bluffs, Reno's force was met by a battalion commanded by Captain Frederick Benteen This force had been on a lateral scouting mission, and had been summoned by Custer to "Come on...big village, be quick...bring pacs..." Benteen's coincidental arrival on the bluffs was just in time to save Reno's men from annihilation. This combined force was then reinforced by a smaller command escorting the expedition's pack train. Benteen did not continue on towards Custer for at least an hour, in spite of the fact that heavy gunfire was heard from the north. Benteen's inactivity prompted later criticism that he had failed to follow orders to "march to the sound of the guns."

The gunfire heard on the bluffs (by everyone except Reno and Benteen) was from Custer's fight. His 210 men engaged the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne (or had been engaged by them) some 3.5 miles to the north. Having driven Reno's force if not into oblivion, at least into chaos, the warriors were free to pursue Custer. The route taken by Custer to his "Last Stand" has been a subject of debate. It does seem clear that after ordering Reno to charge, Custer continued down Reno Creek to within about a half mile of the Little Bighorn, but then turned north, and climbed up the bluffs, reaching the same spot to which Reno would soon retreat. From this point, he could see Reno, on the other side of the river, charging the village.

Custer then rode north along the bluffs, and descended into a drainage called Medicine Tail Coulee, which led to the river. Some historians believe that part of Custer's force descended the coulee, going west to the river and attempting unsucessfully to cross into the village. Other authorities believe that Custer never approached the river, but rather continued north across the coulee and up the other side, where he gradually came under attack. By the time Custer realized he was badly outnumbered by the Indians who came from the Reno fight, according to this theory, it was too late to break through back to the south, where Reno and Benteen could have provided reinforcement.

Within about 2 hours, Custer's battalion was annihilated to the last man. Only two men from the U.S. side later claimed to have seen Custer engage the Indians: a young Crow whose name translated as Curley, and a trooper named Peter Thompson, who had fallen behind Custer's column.

Accounts of the last moments of Custer's forces vary, but all agree that Crazy Horse personally led one of the large groups of Lakota who overwhelmed the cavalrymen. While exact numbers are difficult to determine, it is clear that the Northern Cheyenne and Lakota outnumbered the U.S. force by approximately 3:1, a ratio which was extended to 5:1 during the piecemeal parts of the battle. In addition, some of the Indians were armed with repeating Sharps and Winchester rifles, while the U.S. forces carried single-shot carbines, which had a slow rate of fire, tended to jam, and were difficult to operate from horseback.

After their fight with Custer was finished, the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne came back to attack the remaining US forces under Benteen and Reno, who had finally ventured toward the audible firing of the Custer fight. For 24 hours the outcome of this struggle was in doubt, but Benteen's leadership secured the US lines. At this point, the US forces under Terry approached from the North, and the Indians drew off to the south. The Indian dead had mostly been removed from the field.

The U. S. dead were given hasty burials, and the wounded were given what treatment was available at that time; six would later die of their wounds. Custer was found to have been shot in the temple and in the left chest; either wound would have been fatal. He may also have been shot in the arm. He was found near the top of the hill where the large obelisk now stands, inscribed with the names of the U.S. dead. Most of the dead had been stripped of their clothing, mutilated, and were in an advanced state of deterioration, such that identification of many of the bodies was impossible.

From the evidence, it was impossible to determine what exactly had transpired, but there was not much evidence of prolonged organized resistance. Several days after the battle, the young Crow scout Curly gave an account of the battle which indicated that Custer had attacked the village after crossing the river at the mouth of Medicine Tail Coulee, and had been driven back across the river, retreating up the slope to the hill where his body was later found. This scenario seemed compatible with Custer's aggressive style of warfare, and with some of the evidence found on the ground, and formed the basis for many of the popular accounts of the battle.

Of the U.S. forces killed at Little Bighorn, 210 died with Custer while another 52 died serving under Reno. Six men died later as a result of wounds. Casualty figures on the Indian side included perhaps 40 killed.

The battle was the subject of an army Court of Inquiry in 1879 in which Reno's conduct was scrutinized. Some testimony was presented suggesting that he was drunk, and a coward, but since none of this came from army officers, Reno was not officially condemned. Other factors have been identified which may have contributed to the outcome of the fight: it is apparent that a number of the U.S. troopers were inexperienced and poorly trained. Benteen has been criticized for "dawdling" on the first day of the fight, and disobeying Custer's order. Both Reno and Benteen were heavy drinkers whose subsequent careers were truncated. Terry has been criticized for his tardy arrival on the scene.

Custer's contributions to the U.S. defeat were, at least, faulty intelligence and poor communication, which resulted in an uncoordinated attack against a larger force. For years a debate raged as to whether Custer himself had disobeyed Terry's order not to attack the village until reinforcements arrived. Finally, almost a hundred years after the fight, a document surfaced which indicated that Terry actually had given Custer considerable freedom to do as he saw fit. Custer's widow actively affected the historiography of the battle by suppressing criticism of her husband.

A number of participants decided to wait for her death before disclosing what they knew... however, she outlived almost all of them. As a result, the event was recreated along tragic Victorian lines in numerous books, films and other media. The story of Custer's purported heroic attack across the river, however, was undermined by the account of participant Gall, who told Lieutenant Edward S. Godfrey that Custer never came near the river. Godfrey incorporated this into his important publication in 1892 in The Century Magazine.

In spite of this, however, Custer's legend was embedded in the American imagination as a heroic American officer fighting valiantly against savage forces. By the end of the 20th century, the general recognition of the mistreatment of the various Native American nations in the conquest of the American west, and the perception of Custer's role in it, have changed the image of the battle and of Custer.

The Little Bighorn is now popularly viewed as the confrontation between a reckless and ambitious agent of U.S. expansion against courageous warriors defending their land and way of life. It should be noted that most of the occupants of the large village attacked by Custer were non-combatants.

The memorials to U.S. troops have now been supplemented by markers celebrating the Indians who fought there. Many of the Native Americans in the fight including Crazy Horse played a leading role in this battle and the Battle of Rosebud one week before. On Memorial Day 1999 the first of five red granite markers denoting where warriors fell during the battle were placed on the battlefield for Cheyenne warriors, Lame White Man and Noisy Walking The warrior markers dot the ravines and hillsides like the white marble markers representing where soldiers fell. Since then, markers have been added for the Sans Arc Lakota warrior, Long Road and the Minniconjou Lakota, Dog's Back Bone.

On June 25, 2003 an unknown Lakota warrior marker was placed on Wooden Leg Hill, east of Last Stand Hill to honor a warrior who was killed during the battle as witnessed by the Northern Cheyenne warrior, Wooden Leg. The first Indian Memorial was dedicated on June 25, 2003.

The bill that changed the name of the battlefield from Custer Battlefield National Monument to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument also called for an Indian Memorial to be built near Last Stand Hill. President George H. W. Bush signed the bill into law on December 10, 1991. The Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument is located in southeastern Montana near Crow Agency, Montana and administered by the National Park Service.

Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn, attempts by the U.S. Army to capture and escort the Cheyenne intensified.

A group of 972 Cheyenne were escorted to Indian Territory in Oklahoma in 1877.

There the conditions were dire, the Northern Cheyenne were not used to the climate and soon many became ill with malaria. In 1878, the two principal Chiefs, Little Wolf and Morning Star (Dull Knife) pressed for the release of the Cheyenne so they could travel back north. That same year a group of an estimated 350 Cheyenne left Indian Territory to travel back north.

This group was led by Chiefs Little Wolf and Morning Star. The Army and other civilian volunteers were in hot pursuit of the Cheyenne as they traveled north. It is estimated that a total of 13,000 Army soldiers and volunteers were sent to pursue the Cheyenne. The band soon split.

One group was led by Little Wolf, and the other by Morning Star. Little Wolf and his band made it back to Montana. Morning Star and his band were captured and escorted to Ft. Robinson, Nebraska. There Morning Star and his band were sequestered.

They were ordered to return to Oklahoma but they refused.

Conditions at the fort grew tense through the end of 1878 and soon the Cheyenne were confined to barracks with no food, water or heat.

In January of 1879, Morning Star and his group broke out of Ft. Robinson. Most of the group was gunned down as they ran away from the fort.

It is estimated that only approximately 50 survived the breakout to reunite with the other Northern Cheyenne in Montana.

Through determination and sacrifice, the Northern Cheyenne had earned their right to remain in the north near the Black Hills.

In 1884, by Executive Order, a reservation, the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation was established in southeast Montana. This reservation was expanded in 1890, the current western border is the Crow Indian Reservation and the eastern border is the Tongue River.

For 400 years, the Cheyenne have gone through 4 stages of culture. First they lived in the Eastern Woodlands and were a sedentary/agricultural people, planting corn, and beans.

Next they lived in present day Minnesota/South Dakota and continued their farming tradition and also started hunting the bison of the Great Plains.

During the third stage the Cheyenne abandoned their sedentary/farming lifestyle and became a full-fledged Plains horse culture tribe.

The fourth stage is the reservation phase.

Cheyenne religion recognized two principal deities, the Wise One Above and a God who lived beneath the ground. In addition, four spirits lived at the points of the compass.

The Cheyenne were among the Plains tribes who performed the sun dance in its most elaborate form. They placed heavy emphasis on visions in which an animal spirit adopted the individual and bestowed special powers upon him so long as he observed some prescribed law or practice.

Their most venerated objects, contained in a sacred bundle, were a hat made from the skin and hair of a buffalo cow and four arrows - two painted for hunting and two for battle. These objects were carried in war to insure success over the enemy.

The Cheyenne practiced shamanism - dance, medicine.

Cheyenne Wikipedia