The Ancestral Puebloans were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southwestern Colorado. The Ancestral Puebloans are believed to have developed, at least in part, from the Oshara Tradition, who developed from the Picosa culture.

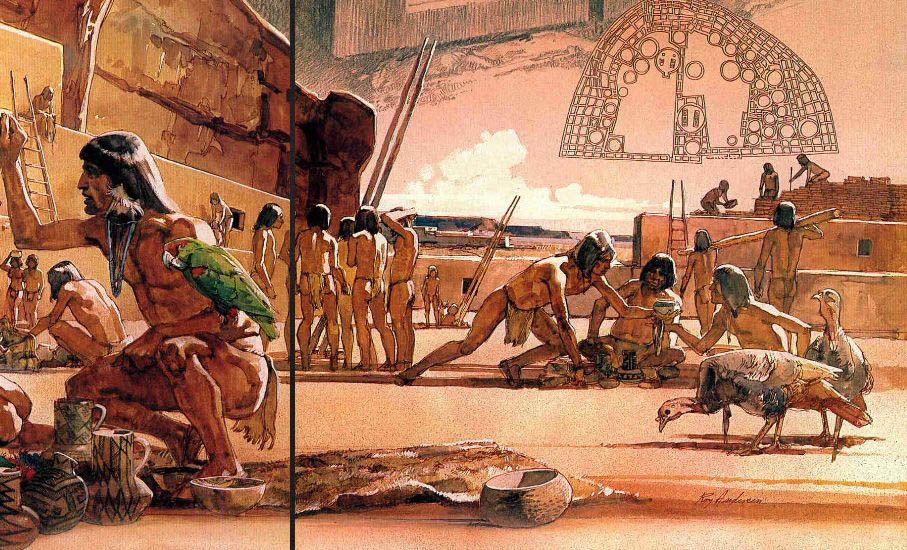

They lived in a range of structures that included small family pit houses, larger structures to house clans, grand pueblos, and cliff-sited dwellings for defense. The Ancestral Puebloans possessed a complex network that stretched across the Colorado Plateau linking hundreds of communities and population centers. They held a distinct knowledge of celestial sciences that found form in their architecture. The kiva, a congregational space that was used chiefly for ceremonial purposes, was an integral part of this ancient people's community structure.

In contemporary times, the people and their archaeological culture were referred to as Anasazi for historical purposes. The Navajo, who were not their descendants, called them by this term. Reflecting historic traditions, the term was used to mean "ancient enemies". Contemporary Puebloans do not want this term to be used.

Archaeologists continue to debate when this distinct culture emerged. The current agreement, based on terminology defined by the Pecos Classification, suggests their emergence around the 12th century BC, during the archaeologically designated Early Basketmaker II Era. Beginning with the earliest explorations and excavations, researchers identified Ancestral Puebloans as the forerunners of contemporary Pueblo peoples. Three UNESCO World Heritage Sites located in the United States are credited to the Pueblos: Mesa Verde National Park, Chaco Culture National Historical Park and Taos Pueblo.

Ancient Pueblo People, or Ancestral Puebloans, is a preferred term for the cultural group of people often known as Anasazi who are the ancestors of the modern Pueblo peoples. The ancestral Puebloans were a prehistoric Native American civilization centered around the present-day Four Corners area of the Southwest United States.

Archaeologists debate when a distinct culture emerged, but the current consensus, based on terminology defined by the Pecos Classification, suggests their emergence around 1200 B.C., the Basketmaker II Era.

They inhabited the area that is present-day Arizona, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico, called the Four Corners. They are known for mud-brick villages located along edges of canyons or atop mesas. The civilization is perhaps best-known for the jakal, adobe and sandstone dwellings that they built along cliff walls, particularly during the Pueblo II and Pueblo III eras.

The best-preserved examples of those dwellings are in parks such as Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Mesa Verde National Park, Hovenweep National Monument, Bandelier National Monument, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument. These villages, called pueblos by Mexican settlers, were often only accessible by rope or through rock climbing.

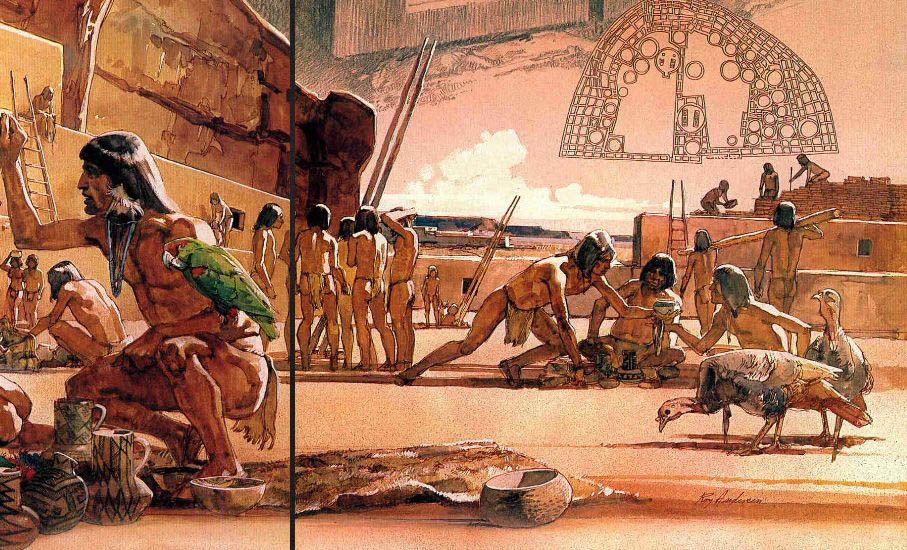

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park hosting the densest and most exceptional concentration of pueblos in the American Southwest. The park is located in northwestern New Mexico, between Albuquerque and Farmington, in a remote canyon cut by the Chaco Wash. Containing the most sweeping collection of ancient ruins north of Mexico, the park preserves one of the most important pre-Columbian cultural and historical areas in the United States.

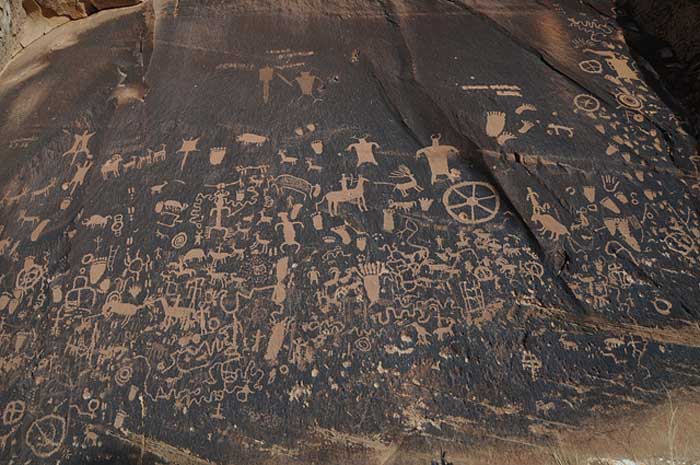

Between AD 900 and 1150, Chaco Canyon was a major center of culture for the Ancient Pueblo Peoples. Chacoans quarried sandstone blocks and hauled timber from great distances, assembling fifteen major complexes that remained the largest buildings in North America until the 19th century. Evidence of archaeoastronomy at Chaco has been proposed, with the "Sun Dagger" petroglyph at Fajada Butte a popular example. Many Chacoan buildings may have been aligned to capture the solar and lunar cycles, requiring generations of astronomical observations and centuries of skillfully coordinated construction. Climate change is thought to have led to the emigration of Chacoans and the eventual abandonment of the canyon, beginning with a fifty-year drought commencing in 1130.

Comprising a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the arid and sparsely populated Four Corners region, the Chacoan cultural sites are fragile Ð concerns of erosion caused by tourists have led to the closure of Fajada Butte to the public. The sites are considered sacred ancestral homelands by the Hopi and Pueblo people, who maintain oral accounts of their historical migration from Chaco and their spiritual relationship to the land. Though park preservation efforts can conflict with native religious beliefs, tribal representatives work closely with the National Park Service to share their knowledge and respect the heritage of the Chacoan culture. Read more

Chaco Culture: Pueblo Builders of the Southwest Live Science - May 23, 2017

The "Chaco Culture," as modern-day archaeologists call it, flourished between roughly the 9th and 13th centuries A.D. and was centered at Chaco Canyon in what is now New Mexico. The people of the Chaco Culture built immense structures that at times encompassed more than 500 rooms. They also participated in long-distance trade that brought cacao, macaws (a type of parrot), turquoise and copper to Chaco Canyon. The people of the Chaco Culture did not use a writing system and as such, researchers have to rely on the artifacts and structures they left behind, as well as oral accounts that have been passed on through generations, to reconstruct what their lives were like.

Archaeologists generally agree that Chaco Canyon was the center of Chaco Culture. Today the canyon is a national park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The National Park Service estimates that there are about 4,000 archaeological sites in the park, including more than a dozen immense structures that archaeologists sometimes call "Great Houses." Archaeological research has revealed many discoveries, including a system of roads that connected many Chaco Culture sites, and evidence of astronomical alignments that indicate that some Chaco Culture structures were oriented toward the solstice sun and lunar standstills.

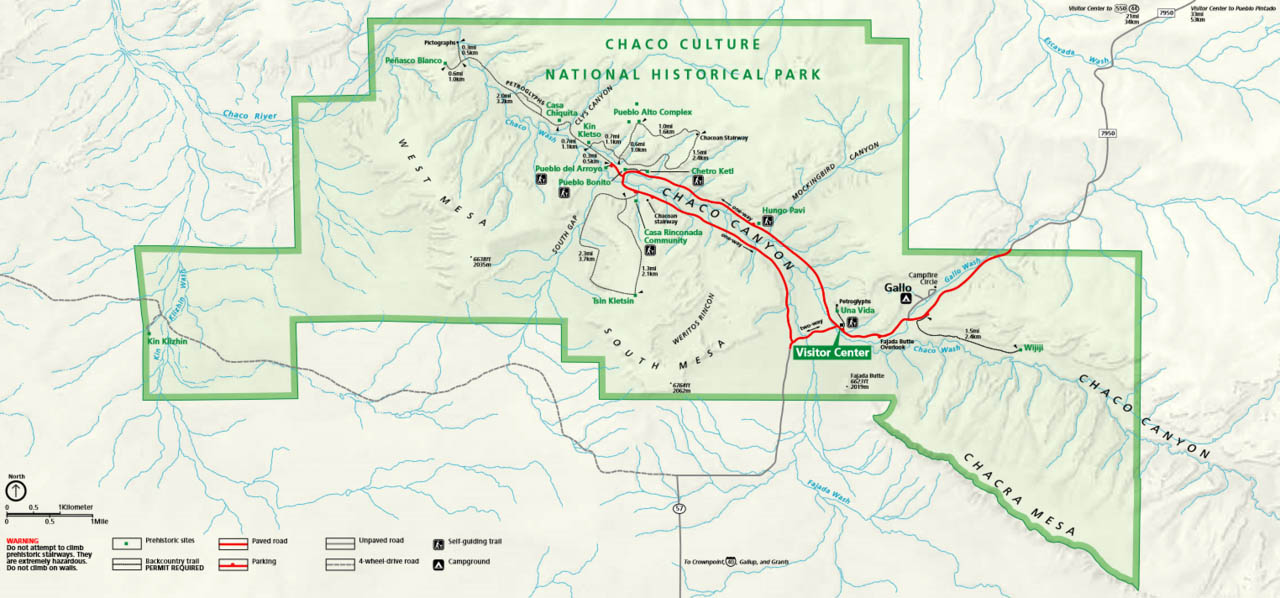

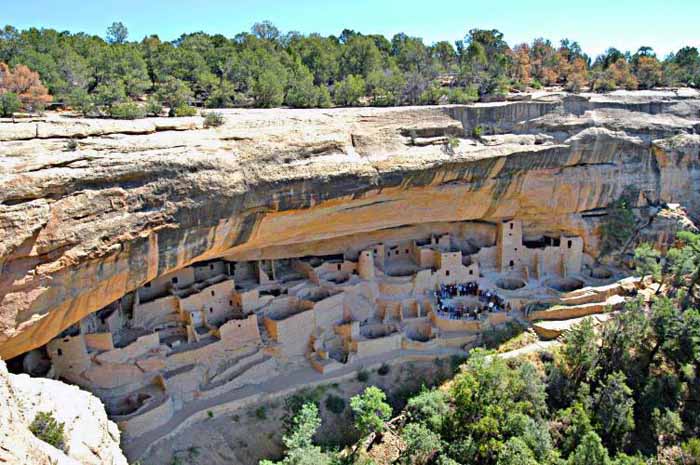

Mesa Verdi was home to the Anasazi Indians for more than 1,000 years. The people that first built their houses here at the time of the Roman Empire farmed the mesas, plateaus, river bottoms, and canyons. They created a thriving, populous civilization that eventually raised towers and built hundred-room cities in the cliffs and caves of Mesa Verde. The Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in North America. The structure built by the Ancient Pueblo Peoples is located in Mesa Verde National Park in their former homeland region. The cliff dwelling and park are in the southwestern corner of Colorado, in the Southwestern United States.

Mesa Verde National Park is a National Park and World Heritage Site located in Montezuma County, Colorado. It protects some of the best preserved Ancestral Puebloan archaeological sites in the United States. Created by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, the park occupies 52,485 acres (21,240 ha) near the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. With more than 4,300 sites, including 600 cliff dwellings, it is the largest archaeological preserve in the U.S. Mesa Verde (Spanish for "green table") is best known for structures such as Cliff Palace, thought to be the largest cliff dwelling in North America.

Starting c.7500 BCE, Mesa Verde was seasonally inhabited by a group of nomadic Paleo-Indians known as the Foothills Mountain Complex. The variety of projectile points found in the region indicates they were influenced by surrounding areas, including the Great Basin, the San Juan Basin, and the Rio Grande Valley. Later, Archaic people established semi-permanent rockshelters in and around the mesa. By 1000 BCE, the Basketmaker culture emerged from the local Archaic population, and by 750 CE the Ancestral Puebloans had developed from the Basketmaker culture.

The Mesa Verdeans survived using a combination of hunting, gathering, and subsistence farming of crops such as corn, beans, and squash. They built the mesa's first pueblos sometime after 650, and by the end of the 12th century, they began to construct the massive cliff dwellings for which the park is best known. By 1285, following a period of social and environmental instability driven by a series of severe and prolonged droughts, they abandoned the area and moved south to locations in Arizona and New Mexico, including Rio Chama, Pajarito Plateau, and Santa Fe. Read more

The typical Anasazi village consisted of buildings housing about 100 men, women and children. Dating back to 700 A.D., shaped, closely fitting stone or adobe (bricks made of sand, clay and straw) masonry formed complex apartment structures rising atop mesas (flat high grounds) or inside natural caves at the base of canyons. The ground-floor apartments were grain storage units while ladders allowed access to the different 10-by-20-foot living compartments above. Crops grown by the villages included maize (corn), gourds, squash, beans and cotton. Different phases of the culture produced finely made baskets and beautifully designed pottery.

Based on current day Pueblo religious practices, archeologists think of the Anasazi kivas (Hopi language for "old house") as sacred chambers for ceremonies. In the kachina cult (ancestral spirits who bring rain), the Anasazi worshiped the sun, fire and serpents for fertility and agricultural productivity. The kiva is a subterranean room reached by ladder through an opening in the roof. The esoteric symbolism of the hole refers to a man leaving the womb of the earth. These sacred places were always separate from the living quarters, with an average of two kivas per village.

This is a culture who came and went, leaving behind stone markers and petroglyphs that suggest that they were visited by - and connected to - Star People, or ancient aliens much like other ancient civilizations.

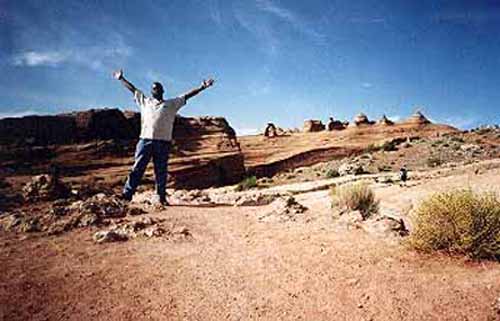

My friends - Anthropologists Steven Stewart and Nicole Torres

Archeological evidence suggests that the Moab area and surrounding country was inhabited by the Anasazi (in Navajo language, the ancient ones). The present town of Moab sits on the ruins of pueblo farming communities dating from the 11th and 12th centuries. These Anasazi Indians mysteriously vacated the Four Corners area around 1300 AD, leaving ruins of their homes scattered throughout the area. The villages were never inhabited again. They were "burned, possibly by the inhabitants, shortly before abandonment.

Could they have been driven out by nomadic tribes, such as Utes or Navajos? There is no direct evidence that either group, or any other like them, was in the area that early. There is mounting evidence, however, that the Numic-speaking peoples, of whom the Utes and Paiutes are part, had spread northwestward out of southwestern Nevada and were in contact with the Pueblo-like peoples of western Utah by A.D. 1200. It is certainly possible that they were in San Juan County shortly after that. Ute and Paiute sites are very difficult to distinguish from Anasazi campsites, and we may not be recognizing them.

Navajos were in northwestern New Mexico by 1500, but we do not know where they were before that. Perhaps the answer to the Anasazis' departure from Utah lies in a combination of the bad-climate and the arriving-nomads theories.

The Ancestral Puebloans migrated from their ancient homeland for several complex reasons. These may include pressure from Numic-speaking peoples moving onto the Colorado Plateau as well as climate change which resulted in agricultural failures.

Confirming evidence for climatic change in North America is found in excavations of western regions in the Mississippi Valley between A.D. 1150 and 1350 which show long lasting patterns of warmer, wetter winters and cooler, dryer summers.

Most modern Pueblo peoples (whether Keresans, Hopi, or Tanoans) and historians like James W. Loewen, in his book Lies Across America, assert these people did not "vanish," as is commonly portrayed, but merged into the various pueblo peoples whose descendants still live in Arizona and New Mexico.

Many modern Pueblo tribes trace their lineage from settlements in the Anasazi area and areas inhabited by their cultural neighbors, the Mogollon. For example, the San Ildefonso Pueblo people believe that their ancestors lived in both the Mesa Verde area and the current Bandelier.

The term "Anasazi" was established in archaeological terminology through the Pecos Classification system in 1927. Archaeologist Linda Cordell discussed the word's etymology and use:

The term was first applied to ruins of the Mesa Verde by Richard Wetherill, a rancher and trader who, in 1888-1889, was the first Anglo-American to explore the sites in that area. Wetherill knew and worked with Navajos and understood what the word meant.

The name was further sanctioned in archaeology when it was adopted by Alfred V. Kidder, the acknowledged dean of Southwestern Archaeology. Kidder felt that is was less cumbersome than a more technical term he might have used. Subsequently some archaeologists who would try to change the term have worried that because the Pueblos speak different languages, there are different words for "ancestor," and using one might be offensive to people speaking other languages.

Some modern Pueblo peoples object to the use of the term Anasazi, although there is still controversy among them on a native alternative. The modern Hopi use the word "Hisatsinom" in preference to Anasazi. However, Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department (NNHPD) spokeman Ronald Maldonado has indicated the Navajo do not favor use of the term "Ancestral Puebloan." In fact, reports submitted for review by NNHPD are rejected if they include use of the term.

Archeologists are not sure why these ancient people deserted the cliff dwellings by the end of the thirteenth century. Some experts think that they ran from attacks from marauding groups of native peoples. Others believe that overuse of the land for agriculture, combined with a long drought, drove the people away.

The ancient Pueblo people constructed sandals from yucca, hemp weed, hair and other fibers by weaving them on large, upright loom frames. Soles for sandals and moccasins were made of rawhide. Moccasins were constructed of deerskin and sewn with sinew. Matted fibers from juniper bark, which has soft fibers that separate and can be peeled from the bark, were used to insulate sandals and moccasins in cold weather. Fresh goatskins with the hairy side turned inward were worn to encase the feet in snowy weather. Brand new moccasins, sandals or thongs were placed on the dead before burial.

Pueblo women wore a garment made of hundreds of yucca fiber strands covering the buttocks, similar to a beech cloth flap. The men didn't wear much clothing in warm weather except for a belt of woven hair and grasses, necessary to hang tools and items they may need for hands-free hunting and weaving. When sheep were introduced into the villages of the Pueblo people, they began weaving wool for clothing, and years later, cotton for clothing, which was much cooler in warm weather.

Pueblo people enjoyed decorative jewelry. They constructed them out of stone beads, seeds, feathers, coral, bones, shells, abalone and stones. Items were polished, punched, carved and engraved to create jewelry of almost every kind, such as bracelets, arm bands, earrings, necklaces, pins and ankle bracelets for both men and women. Jewelry was often placed in graves with the dead, along with pottery created especially for the burial ceremony. After the Pueblos learned silversmithing from the Spaniards in the 1800s, metal jewelry was integrated into the jewelry materials they were previously using.

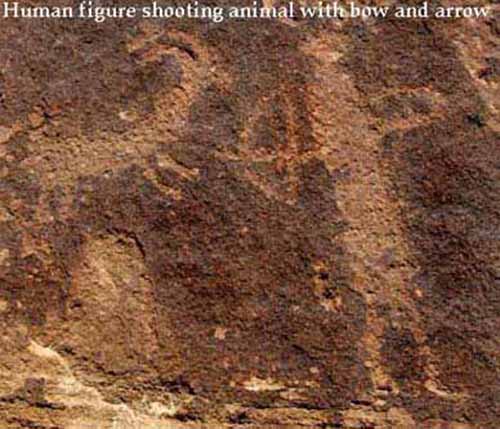

The Ancestral Puebloans are also known for their unique style of pottery, today considered valuable for their rarity. They also created many petroglyphs and pictographs.

Archaeological cultural units such as "Anasazi", Hohokam, Patayan or Mogollon are used by archaeologists to define material culture similarities and differences that may identify prehistoric socio-cultural units which may be understood as equivalent to modern tribes, societies or peoples. The names and divisions are classificatory devices based on theoretical perspectives, analytical methods and data available at the time of analysis and publication. They are subject to change, not only on the basis of new information and discoveries, but also as attitudes and perspectives change within the scientific community. It should not be assumed that an archaeological division or culture unit corresponds to a particular language group or to a socio-political entity such as a tribe.

When making use of modern cultural divisions in the American Southwest, it is important to understand three limitations in the current conventions:

Arizona Republic - June 2004

Range Creek area southeast of East Carbon City, Utah Archaeologists led reporters into a remote canyon to reveal an almost perfectly preserved picture of ancient life: stone pit houses, granaries and a bounty of artifacts kept secret for more than a half-century. Hundreds of sites on a private ranch turned over to the state offer some of the best evidence of the little-understood Fremont culture, hunter-gatherers and farmers who lived mostly within the present-day borders of Utah. The sites at Range Creek may be up to 4,500 years old.

A caravan of news organizations traveled for two hours from the mining town of East Carbon City, over a serpentine thriller of a dirt road that topped an 8,200-foot mountain before dropping into the narrow canyon in Utah's Book Cliffs region. Officials kept known burial sites and human remains out of view of reporters and cameras, but within a single square mile of verdant meadows, archaeologists showed off one village site and said there were five more, where arrowheads, pottery shards and other artifacts can still be found lying on the ground. Archaeologists said the occupation sites, which include granaries full of grass seed and corn, offer an unspoiled slice of life of the ancestors of modern American Indian tribes. The settlements are scattered along 12 miles of Range Creek and up side canyons.

The collapsing half-buried houses don't have the grandeur of New Mexico's Chaco Canyon or Colorado's Mesa Verde, where overhanging cliffs shelter stacked stone houses. But they are remarkable in that they hold a treasure of information about the Fremont culture that has been untouched by looters. The Fremont people were efficient hunters, taking down deer, elk, bison and small game and leaving behind piles of animal bone waste, Jones said. They fished for trout in Range Creek, using a hook and line or weirs. In their more advanced stage they grew corn.

Waldo Wilcox, the rancher who sold the land and returned Wednesday, kept the archaeological sites a closely guarded secret for more than 50 years. The San Francisco-based Trust for Public Land bought Wilcox's 4,200-acre ranch for $2.5 million. The conservation group transferred the ranch to the Bureau of Land Management, which turned it over to Utah. The deal calls for the ranch to be opened for public access, a subject certain to raise debate over the proper stewardship of a significant archaeological find.

Reconstructed Pithouse - State Park, Boulder, Utah

The Fremont culture or Fremont people, named by Noel Morss of Harvard's Peabody Museum after the Fremont River in Utah, is an archaeological culture that inhabited what is now Utah and parts of eastern Nevada, southern Idaho, southern Wyoming, and eastern Colorado between about 400 and 1300 AD.

The Fremont culture unit was characterised by small, scattered communities that subsisted primarily through maize cultivation. Archaeologists have long debated whether the Fremont were a local Archaic population that adopted village-dwelling life from the neighboring Anasazi culture to the south, or whether they represent an actual migration of Basketmakers (the earliest culture stage in the Anasazi Culture) into the northern American Southwest or the area that Julian Steward once called the "Northern Periphery".

The Fremont have some unique material culture traits that mark them as a distinct and identifiable archaeological culture unit, and recent mtDNA data indicate they are a biologically distinct population, separate from the Basketmaker. What early archaeologists such as Morss or Marie Wormington used to define the Fremont was their distinctive pottery, particularly vessel forms, incised and applique decorations, and unique leather moccasins. However, their house forms and overall technology are virtually indistinguishable from the Anasazi. Their habitations were initially circular pit-houses but they began to adopt rectangular stone-built pueblo homes above ground.

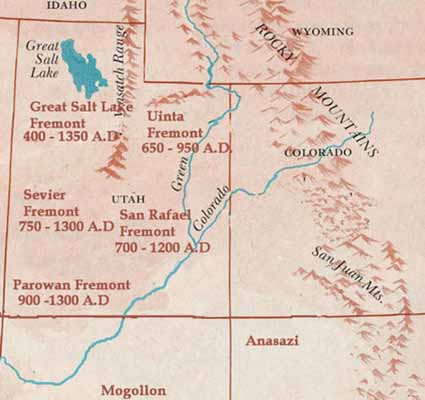

Marwitt (1970) defined local or geographic variations within the Fremont culture area based largely on differences in ceramic production and geography. Marwitt's subdivisions are the Parowan Fremont in southwestern Utah, the Sevier Fremont in west central Utah and eastern Nevada, the Great Salt Lake Fremont stretching between the Great Salt Lake and the Snake River in southern Idaho, Uinta Fremont in northeastern Utah, and arguably the San Rafael Fremont in eastern Utah and western Colorado. (The latter geographic variant may well be indivisible from the San Juan Anasazi.)

National Geographic - September 28, 2001

Some of America's earliest high-rise architects lived in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, between the tenth and twelfth centuries. Here these Anasazi designers and engineers built 12 great houses up to five stories high with hundreds of rooms. However, where the Chaco residents harvested the lumber for these enormous buildings is a question that has stumped archaeologists. Now scientists have found a way to let ancient timbers tell their secrets. Geochemist Nathan English, of the University of Arizona, has developed a chemical test to determine the origin of these trees.

In the same way that human bones absorb and store calcium from food, trees take up the element strontium. Exactly how much is absorbed depends on the quantity in the surrounding soil and rock where the tree grows. The test is based on comparing ratios of two strontium isotopes from wooden construction beams in the Chaco houses with measurements taken from modern trees in the surrounding mountain ranges.

The 12 Chaco dwellings together contain about 200,000 wooden beams that were used to construct the roofs. But the Chaco Canyon is an almost treeless landscape that was certainly never the source of the timber. When English analyzed the strontium ratios from the timber used to construct the houses, they matched those from spruce and pine trees located on mountaintops up to 60 miles (100 kilometers) away in the Chuska and San Mateo mountain ranges.It is amazing that the Chaco dwellers carried thousands of these enormous logs most of which measured about 5 meters (15 feet), about 22 cm (9 inches) in diameter and weighed about 275 kilograms (600 pounds) for up to one hundred kilometers, said English."

These findings amplify our suspicions that these people were tremendously well organized and socially powerful," says archaeologist Jeffrey Dean, also of the University of Arizona. It takes a lot of determination and coordination to harvest logs from up to 100 kilometers away and bring them back to the village, he added.English's team also found wood within single rooms that came from both the Chuska and San Mateo mountains, and that trees from different great houses were harvested in the same year.