Extensive Mayan salt trade discovered MSNBC - March 2005

Small entrepreneurs distilled salt and peddled it along coast

Extensive Mayan salt trade discovered MSNBC - March 2005

Small entrepreneurs distilled salt and peddled it along coast

Mystery of 'chirping' pyramid decoded Nature Magazine - December 14, 2004

Maya culture 'ahead of its time' BBC - May 2004

Ancient map captures ocean front New Scientist - May 2004

Giant masks reveal early Maya sophistication

Archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli is dwarfed by the enormous stucco

face of a Maya deity at a little-known site in Guatemala called Cival.

Archaeologists Uncover Maya "Masterpiece" in Guatemala National Geographic - April 2004

Archaeologists working deep in Guatemala's rain forest under the protection of armed

guards say they have unearthed one of the greatest Maya art masterpieces ever found.

The artifact - a 100-pound (45-kilogram) stone panel carved with images and hieroglyphics -

depicts Taj Chan Ahk, the mighty 8th-century king of the ancient Maya city-state of Cancuén -

excavation of royal mayan palace.

Ancient Nicaraguan society found BBC - May 2003

Archaeologists discover a previously unknown ancient Pre-Mayan

civilisation in Central America that developed around 2,700 years

ago and lasted for a thousand years.

New Discovery in Palenque Mesoweb.com

On October 10, 2002, Palenque site director Juan Antonio Ferrer announced a new discovery from just south of the Cross Group. A stone tablet with an elaborate scene and numerous hieroglyphs carved in relief was found on the side of a low platform in Temple XXI. It now joins the canon of historically vital and stunningly beautiful monuments from this Classic Maya site in Chiapas, Mexico.

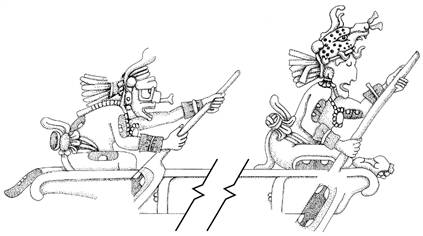

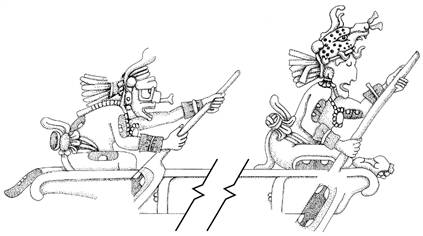

K'inich Ahkal Mo' Nahb' III himself is the left-side figure in the sculptured relief. A caption for the central figure, seated on a jaguar-skin covered throne, states that he is impersonating a deity (or deified ancestor) whose name ends in U "K'ix" Chan. This name appears in Palenque's royal genealogy with a supposed time of rulership dating to the Olmec era (he is said to have been born in 993 BC).

May 2002 - News in Science

The ancient Maya may have dug caves with spiritual abandon.

For more than 100 years, archaeologists have hacked through jungles in Mexico and Central America in a quest to uncover pyramids, temples, and other majestic ruins of Maya civilization. James E. Brady of California State University, Los Angeles appreciates the backbreaking work that goes into finding such monumental structures, but he has his sights set lower.

As he's probed the ancient Maya's sacred landscape, he's come to realize that this group's belief system invested immense supernatural power in caves and the mountains that surround them.

Brady heads up a growing band of researchers who are piecing together this subterranean, spiritual perspective. In their view, a supernatural terrain permeated pre-Columbian religious life from central Mexico through much of Central America and still inspires faith in many native groups.

Caves occupy the focal point of this archaeological project. In initial research, Brady discovered that some of the largest Maya outposts of the Classic period, which lasted from A.D. 200 to A.D. 900, were strategically oriented on and around natural and humanmade caves (

As entryways through sacred, living earth into an underworld of gods, mythical creatures, and ancestors, caves served as spiritual landmarks. In these dim chambers, rulers conducted ceremonies vital to maintaining their power.

New discoveries from before and during the Classic period indicate that caves had considerable spiritual standing in rural as well as urban areas and among common folk as well as rulers. In some locales, caves also show signs of having been visited regularly by religious pilgrims. For example, clues point to cave visits by Maya scribes, the artisans who recorded the royals' exploits.

Cave supply responded to the intense spiritual demands, Brady says. Rather than rely on a limited supply of natural caves, the Maya created new caves in huge numbers. "Artificial caves were constructed according to fairly regular plans and should be considered a formal architectural type of the ancient Maya, just like their ball courts and pyramids," Brady contends. "I suspect there are thousands of these artificial caves that have yet to be discovered."

Artificial caves assume particular prominence in the researchers' latest fieldwork, which Brady and others described this March in Denver at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology.

Maya farmers living far from the madding crowds of major cities excavated their own caves out of dirt or rock apparently to serve as the religious heart of their communities. In some areas, pits that represented caves were dug in houses for family-based rituals, according to Brady.

Moreover, from about 1500 B.C. to A.D. 1400, rural Maya buried their dead in specially designated rock shelters and caves, often dug out of hills or mountains by the sweat of many brows. Among the Classic Maya and their non-Maya contemporaries in central Mexico, a tradition of cave burials may have prompted the construction of pyramids, as symbols of sacred mountains, encasing deceased royalty in cavelike tombs. Seven caves of creation

Around 1,000 years ago in central Mexico, the Chichimec people founded a town known as Acatzingo Viejo. In the center of the site, settlers excavated seven small caves out of a steep limestone slope. This cave array represented Chicomoztoc, seven mythical caverns from which Chichimec ancestors were believed to have first emerged, says Manuel Aguilar of Cal State, Los Angeles.

The group of caves also put a spiritual stamp of approval on Acatzingo Viejo and affirmed the legitimacy of its new rulers, Aguilar proposes.

He and his coworkers found stone altars, ceramic incense burners, and other evidence of past ritual activity in the six surviving caves at the Mexican site. Local residents told the researchers that the seventh cave had recently been destroyed to make room for a new road.

The caves lie just below the remains of a ceremonial plaza that includes a small pyramid. Other central-Mexican sites pair artificial caves with pyramids, Aguilar notes. For example, there's an artificial cave beneath the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan, where a separate civilization thrived at around the time of the Maya's Classic period.

This pyramid contains stone drains that may have channeled rainwater into the chamber to intensify its connection to the spiritual underworld. Some archaeologists suspect that the drains simply collected water for a well. However, their impractical positioning directly under a pyramid betrays their spiritual significance, Aguilar argues.

Spanish documents from the 16th century and scientists' interviews of the area's current inhabitants reveal a longstanding regional belief that water originates in mountains and issues out of caves. Native groups in Mexico and Central America have long regarded caves with water sources as symbols of "the generative womb of the Earth" that gave birth to humanity, Aguilar says.

An intricate replication of a water-bearing cave has been discovered at Muklebal Tzul, a 1,100-year-old Maya site in a mountainous region of southern Belize. In 1999, a team led by Keith M. Prufer of Southern Illinois University in Carbondale noticed a spot next to the settlement's ceremonial center where large amounts of earth had been cleared to create a flat expanse.

On closer inspection, they uncovered what they regard as an artificial cave that descends beneath that area. The structure consists of a narrow, 50-foot-long diagonal tunnel leading down to an open area with a 7-gallon, plaster-lined basin for collecting water. An underground spring supplied water that fell into the basin from a small opening in the tunnel's side, creating an artificial waterfall. The small quantity of water yielded by such a major construction project argues against its use as a well, Prufer says.

"[This project] was intended to reproduce a water-bearing cave on a miniature scale, allowing the residents of the site to center their community over a feature with mythic and sacred qualities," Prufer holds.

Artificial caves had a domestic side as well, according to Brady. In the southern lowlands of Guatemala and Honduras, where natural caves are scarce, ancient Maya houses frequently contain large earthen pits known as chultuns. Separate chambers built into the sides of chultuns were big enough for a person to crawl into, and many include wall niches in which pottery and other items were placed.

Although chultuns have attracted relatively little systematic research, the ancient Maya probably regarded them as household caves in which to conduct rituals, Brady asserts. Hundreds of such chultuns dot the residential landscape of major Classic-era sites such as Tikal in Guatemala.

Nearer to the gods

Contrary to traditional theories, complex Maya beliefs may have inspired poor folk in the hinterlands as much as they did the governing elite in Classic-era centers.

Crucial evidence for this possibility comes from discoveries of rural Maya burials in rock shelters. These structures consist of stone walls erected around depressions in hills or mountains. In poor communities, rock shelters were used to bury the dead at the gate of mythical "creation caves," says David M. Glassman of Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos.

In contrast, ancient Maya royalty were buried in tombs that symbolized caves and in some cases even contain artificial stalactites, Glassman asserts. Upon dying, Maya bigwigs thus gained direct access to the supernatural underworld that had issued their founding ancestors.

"All settlements, large and small, shared the religious ideology of the Maya elite, yet expressed and celebrated it in different ways and with different resources," Glassman contends.

In the Maya Mountains of southern Belize, he and his colleagues have excavated a rock shelter located just below the entrance to a natural cave. The shelter contains skeletal remains of more than 150 people, all lying in a flexed position facing the cave's entrance. Items placed in the graves include pottery, obsidian blades, and various types of rock.

In the past few years, other researchers have found other rock-shelter cemeteries in the same region of Belize.

Prufer's group discovered human skeletons in three natural rock shelters high in the Maya Mountains, not far from the ruins of Muklebal Tzul. Skeletal remnants of 13 individuals have been tallied so far.

Pottery styles and radiocarbon dates indicate that these rock shelters were used as cemeteries as early as 300 B.C., several centuries before intensive settlement of the area.

Soil in each of the burial sites contains dense concentrations of shells from a freshwater snail eaten by the ancient Maya. Large numbers of these shells have also turned up at the entrances to 16 Maya caves that were used for ritual activities. Prufer says that the shells were associated with sacred concepts of water, fertility, birth, and death.

Modern Maya groups continue to revere these snails. Several anthropologists have discovered offerings of snail shells recently left in niches at cave openings.

In 2001, Brady and his coworkers uncovered human graves in four of seven caves in a small, isolated, Guatemalan hill called Balam Na. The badly looted caves also yielded pottery and beads that date to times before the Classic period. When the researchers found the caves, pieces of crude stone walls lay at the entrances, indicating that these sacred sites had once been closed off.

The topmost cave appears to have entombed high-ranking individuals. That arrangement reflects an attempt to protect their graves from pillaging by invading groups, says Cal State's Sergio Garza.

The vulnerability of cave burials to theft may have encouraged the Classic-period tradition of placing royals in pyramid-covered tombs that symbolized caves within hills, Garza proposes.

Ancient-Maya cave activities may have taken other intriguing turns. For instance, caves on Cozumel, an island off the coast of southeast Mexico, exhibit signs of having regularly been visited by religious pilgrims, says Cal State's Shankari Petel. The focus of worship on the island was Ix Chel, the Maya goddess of the moon, childbirth, fertility, and medicine.

Accounts of 16th-century Spanish explorers described Cozumel as a destination for Maya pilgrims. However, archaeologists have shown little interest in probing for evidence of pilgrimages on the island, Petel says. They have portrayed Cozumel's caves variously as pottery dumps, rock quarries, burial sites, and places where people hid during times of social conflict.

Remains of ritual activity, including incense burners, conch shells, and pottery, have been recovered in caves at two Classic-era settlements on Cozumel, according to Petel. Scattered masonry blocks in the caves were probably used to build walls near their entrances. Some of the caves contain cenotes, or openings to underground water sources, that the ancient Maya associated with Ix Chel.

Maya scribes, the artists who used a complex writing system to record the activities of the royalty, conducted their own pilgrimages to certain caves, proposes Andrea Stone, an art historian at the University of WisconsinMilwaukee.

Cave paintings at Naj Tunich, a Classic-era city in Guatemala, contain numerous images of scribes, in what appear to be self-portraits. Accompanying text includes the scribes' names. Other pieces of Maya art, such as an elaborate painted vase found at Naj Tunich more than 20 years ago, contain scenes that scholars now say situate scribes among cave symbols.

Scribes portrayed themselves in distinctive costumes, Stone says. They wear cloth head wraps into which paintbrushes are tucked and quill pens are tied with knotted cords. Many scribes sport spiky hairdos that poke through their headgear. In the portraits, scribes often appear in or near open skeletal jaws, which symbolized caves. Pictorial symbols of stone, water, and death usually surround the scribes.

On cave walls at Naj Tunich, scribes documented their own ritual pilgrimages to invigorate their ties to underworld gods and initiate novice practitioners, Stone theorizes.

May 2002 - San Francisco Gate

For half a century, scholars have searched in vain for the source of the jade that the early civilizations of the Americas prized above all else and fashioned into precious objects of worship, trade and adornment.

The searchers found some clues to the source of jadeite, as the precious rock is known, for the Olmecs and Mayas. But no lost mines came to light.

Now, scientists exploring the wilds of Guatemala say they have found the mother lode -- a mountainous region roughly the size of Rhode Island strewn with huge jade boulders, other rocky treasures and signs of ancient mining. It was discovered after a hurricane tore through the landscape and exposed the veins of jade, some of which turned up in stores, arousing the curiosity of scientists.

The find includes large outcroppings of blue jade, the gemstone of the Olmecs, the mysterious people who created the first complex culture in pre- Columbian Mesoamerica, the region that encompasses much of Mexico and Central America. It also includes an ancient mile-high road of stone that runs for miles through the densely forested region.

The deposits rival the world's leading source of mined jade today, in Burma, the experts say.

The implications for history, archaeology and anthropology are just starting to emerge.

For one thing, the scientists say, the find suggests that the Olmecs, who flourished on the southern Gulf Coast of Mexico, exerted wide influence in the Guatemalan highlands as well. All told, they add, the Guatemalan lode was worked for millenniums, compared with centuries for the Burmese one.

In part, the discovery is a result of the devastating storm that hit Central America in 1998, killing thousands of people and touching off floods and landslides that exposed old veins and washed jade into river beds. Local prospectors picked up the precious scraps, which found their way into Guatemalan jewelry shops and, eventually, the hands of astonished scientists.

Led by Seitz and local jade hunters, a team of scientists from the American Museum of Natural History, Rice University and UC Riverside scoured the forested ravines of the Guatemalan highlands for more than two years.

In the end the scientists made a series of discoveries culminating in bus- size boulders of Olmec blue jade. The exact locations of the outcroppings are not being given, to protect them.

Early peoples of the Americas considered jade more valuable than gold and silver. The Olmecs, the great sculptors of the pre-Columbian era, carved jades into delicate human forms and scary masks. Maya kings and other royalty often went to their graves with jade suits, rings and necklaces. The living had their teeth inlaid with the colored gems.

May 29, 2001 - Reuters - Tegucigalpa, Honduras

The jade-encrusted remains of a powerful Mayan king have been unearthed in Honduras by a Japanese archeologist in a key finding from the ancient and mysterious civilization, the tourism ministry said on Friday.

The remains belong to one of the 16 rulers of the Mayan dynasty that ruled the city of Copan, in what is now Honduras, between 426 and 763 A.D., the ministry said.

Archeologist Seiichi Nakamura, who made the discovery, said the king may have served between the 6th and 10th regimes of the Copan dynasty.

The tomb contained a skull, a femur and an ornamental breastplate and kneecap with jade inlays. It was dug up in August but was only recently confirmed to hold the remains of a Mayan king.

The discovery means that the remains of eight of Mayan's 16 rulers of Myan have now been found.

The burial site was located at a religious temple that lies among ruins stretching across some 214,000 square feet. Some 20 recoverable buildings, 36 skeletal remains, 10 religious offerings, 37 ceramic vessels and other objects were also found at the site.

The newly uncovered area is about 2 miles from the acropolis of Copan, where the Honduras government is constructing a highway.

The Mayan culture sprung up in the region spanning southern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras and is renowned for its imposing edifices, social organization, astrological advances and the existence of a calendar.

Archeologists and scientists still do not fully understand the causes of the civilization's decline.

The Mayan ruins in Honduras are among the impoverished nation's most visited tourist attractions.

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF ALL FILES