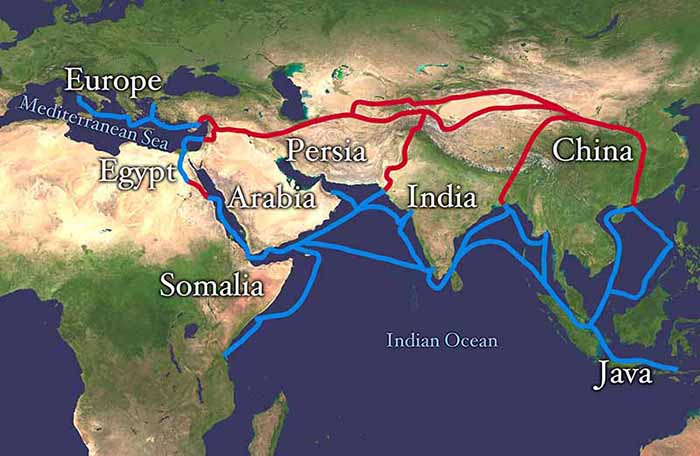

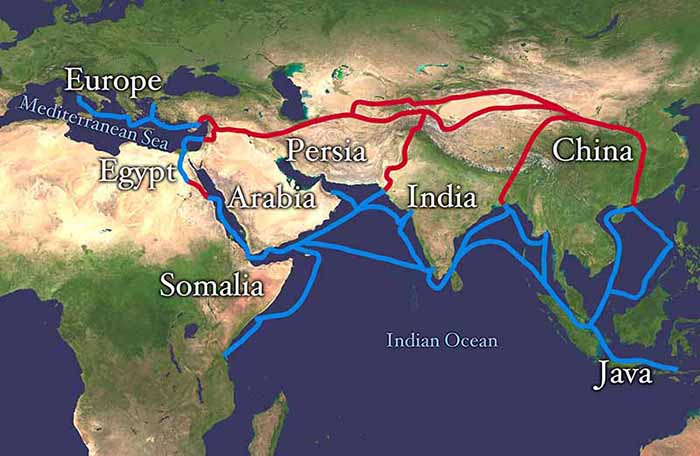

�The Silk Road, or Silk Route, is a series of trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural interaction through regions of the Asian continent connecting the West and East by linking traders, merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads, and urban dwellers from China and India to the Mediterranean Sea during various periods of time.

Extending 4,000 miles (6,437 kilometres), the Silk Road derives its name from the lucrative trade in Chinese silk carried out along its length, beginning during the Han Dynasty (206 BC Ð 220 AD) following the establishment by Alexander the Great of a system of Hellenistic kingdoms (323 BC - 63 BC) and trade networks extending from the Mediterranean to modern Afghanistan and Tajikistan on the borders of China.

The Central Asian sections of the trade routes were expanded around 114 BC by the Han dynasty, largely through the missions and explorations of Chinese imperial envoy, Zhang Qian. The Chinese took great interest in the safety of their trade products and extended the Great Wall of China to ensure the protection of the trade route.

Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in the development of the civilizations of China, the Indian subcontinent, Persia, Europe, and Arabia, opening long-distance, political and economic interactions between the civilizations. Though silk was certainly the major trade item from China, many other goods were traded, and religions , syncretic philosophies, and various technologies , as well as diseases , also travelled along the Silk Routes. In addition to economic trade, the Silk Road served as a means of carrying out cultural trade among the civilizations along its network.

The main traders during antiquity were the Chinese, Persians, Greeks, Syrians, Romans, Armenians, Indians, and Bactrians, and from the 5th to the 8th century the Sogdians. During the coming of age of Islam, Arab traders became prominent.

The last missing link on the Silk Road was completed in 1994, when the international railway between Almaty in Kazakhstan and Urumqi in Xinjiang opened.

As long as two thousand years ago, during the Eastern Han Dynasty in China, the sea route led from the mouth of the Red River near modern Hanoi, all the way through the Malacca Straits to Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka and India, and then on to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. From ports on the Red Sea goods, including silks, were transported overland to the Nile and then down to Alexandria from where they were shipped to Rome and other Mediterranean ports.

Another branch of these sea routes led down the East African coast (called Azania by the Greeks and Romans and Zesan by the Chinese) at least as far as the port known to the Romans as Rhapta, which was probably located in the delta of the Rufiji River in modern Tanzania.

The Silk Road on the Sea extends from southern China to present day Brunei, Thailand, Malacca, Ceylon, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Iran. In Europe it extends from Israel, Lebanon, Egypt, and Italy in the Mediterranean Sea to Portugal and Sweden.

As accomplished waterway shipping and domestication of efficient pack animals both increased the capacity for prehistoric peoples to carry heavier loads over greater distances, cultural exchanges and trade developed rapidly. For example, shipping in predynastic Egypt was already established by the 4th millennium BC along with domestication of the donkey, with the dromedary possibly having been domesticated as well. Domestication of the Bactrian camel and use of the horse for means of transport then followed.

As the domestication of efficient pack animals and the development of shipping technology both increased the capacity for prehistoric peoples to carry heavier loads over greater distances, cultural exchanges and trade developed rapidly.

Just as waterways provide easy means for distant transport, broad stretches of grasslands - all the way from the shores of the Pacific to Africa and deep into the heart of Europe - provide fertile passage for grazing, plus water and fuel for caravans. These waterway and overland routes allowed passage that avoided trespassing on agricultural lands, presenting ideal conditions for caravans, merchants and warriors to travel immense distances without arousing the hostility of more settled peoples.

While goods and religious ideas may have communicated greater distances, ancient trade was probably conducted over only sections of the routes. The Silk Road is unlikely to have been travelled in entirety between Africa, Europe or the Middle East and China by land.

The ancient peoples of the Sahara imported domesticated animals from Asia between 7500 and 4000 BC.

Foreign artifacts dating to the 5th millennium BC in the Badarian culture of Egypt indicate contact with distant Syria.

In predynastic Egypt, by the 4th millennium BC shipping was well established, and the donkey and possibly the dromedary had been domesticated. Domestication of the Bactrian camel and use of the horse for transport then followed.

Also by the beginning of the 4th millennium BC, ancient Egyptians in Maadi were importing pottery as well as construction ideas from Canaan.

By the second half of the 4th millennium BC, the gemstone lapis lazuli was being traded from its only known source in the ancient world - Badakshan, in what is now northeastern Afghanistan - as far as Mesopotamia and Egypt. By the 3rd millennium BC, the lapis lazuli trade was extended to Harappa and Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley Civilization of modern day Pakistan and northwestern India. The Indus Valley was also known as Meluhha, the earliest maritime trading partner of the Sumerians and Akkadians in Mesopotamia.

Routes along the Persian Royal Road, constructed in the 5th century BC by Darius I of Persia, may have been in use as early as 3500 BC. Charcoal samples found in the tombs of Nekhen, which were dated to the Naqada I and II periods, have been identified as cedar from Lebanon.

In 1994 excavators discovered an incised ceramic shard with the serekh sign of Narmer, dating to circa 3000 BC. Mineralogical studies reveal the shard to be a fragment of a wine jar exported from the Nile valley to Israel.

The ancient harbor constructed in Lothal, India, may be the oldest sea-faring harbour known.

The Palermo stone mentions King Sneferu of the 4th Dynasty sending ship to import high-quality cedar from Lebanon. In one scene in the pyramid of Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty, Egyptians are returning with huge cedar trees. Sahure's name is found stamped on a thin piece of gold on a Lebanon chair, and 5th dynasty cartouches were found in Lebanon stone vessels. Other scenes in his temple depict Syrian bears. The Palermo stone also mentions expeditions to Sinai as well as to the diorite quarries northwest of Abu Simbel.

The oldest known expedition to the Land of Punt was organized by Sahure, which apparently yielded a quantity of myrrh, along with malachite and electrum. The 12th-Dynasty Pharaoh Senusret III had a "Suez" canal constructed linking the Nile River with the Red Sea for direct trade with Punt.

Around 1950 BC, in the reign of Mentuhotep III, an officer named Hennu made one or more voyages to Punt. In the 15th century BC, Nehsi conducted a very famous expedition for Queen Hatshepsut to obtain myrrh; a report of that voyage survives on a relief in Hatshepsut's funerary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Several of her successors, including Thutmoses III, also organized expeditions to Punt.

The expansion of Scythian Iranian cultures stretching from the Hungarian plain and the Carpathians to the Chinese Kansu Corridor and linking Iran, and the Middle East with Northern India and the Punjab, undoubtedly played an important role in the development of the Silk Road. Scythians accompanied the Assyrian Esarhaddon on his invasion of Egypt, and their distinctive triangular arrowheads have been found as far south as Aswan. These nomadic peoples were dependent upon neighbouring settled populations for a number of important technologies, and in addition to raiding vulnerable settlements for these commodities, also encouraged long distance merchants as a source of income through the enforced payment of tariffs. Soghdian Scythian merchants were in later periods to play a vital role in the development of the Silk Road.

Britain had large reserves of tin in the areas of Cornwall and Devon in what is now southwest England. By around 1600 BC the southwest of Britain was experiencing a trade boom, as mined British tin was being exported across Europe. When the Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age around the Mediterranean the shipping of tin ended between 1200 and 1100 BC. No land route has ever been found between ancient Britain and Mediterranean civilizations.

From the 2nd millennium BC nephrite jade was being traded from mines in the region of Yarkand and Khotan to China. Significantly, these mines were not very far from the lapis lazuli and spinel ("Balas Ruby") mines in Badakhshan and, although separated by the formidable Pamir mountains, routes across them were, apparently, in use from very early times.

The Tarim mummies, Chinese mummies of an Indo-European type, have been found in the Tarim Basin, such as in the area of Loulan located along the Silk Road 200 kilometers east of Yingpan, dating to as early as 1600 BC and suggesting very ancient contacts between East and West. It has been suggested that these mummified remains may have been the work of the ancestors of the Tocharians whose Indo-European language remained in use in the Tarim Basin (modern day Xinjiang) of China until the 8th century CE.

Some remnants of what was probably Chinese silk have been found in Ancient Egypt from 1070 BC. Though the originating source seems sufficiently reliable, silk unfortunately degrades very rapidly and we cannot double-check for accuracy whether it was actually cultivated silk (which would almost certainly have come from China) that was discovered or a type of "wild silk," which might have come from the Mediterranean region or the Middle East.

Following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western and northwestern border territories in the 8th century BC, gold was introduced from Central Asia, and Chinese jade carvers began to make imitation designs of the steppes, adopting the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat). This style is particularly reflected in the rectangular belt plaques made of gold and bronze with alternate versions in jade and steatite.

By the time of Herodotus (c. 475 BC) the Persian Royal Road ran some 2,857 km from the city of Susa on the lower Tigris to the port of Smyrna (modern Izmir in Turkey) on the Aegean Sea. It was maintained and protected by the Achaemenid empire (c.700-330 BC) and had postal stations and relays at regular intervals. By having fresh horses and riders ready at each relay, royal couriers could carry messages the entire distance in 9 days, though normal travellers took about three months. This Royal Road linked into many other routes. Some of these, such as the routes to India and Central Asia, were also protected by the Achaemenids, encouraging regular contact between India, Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean. There are accounts in Esther of dispatches being sent from Susa to provinces as far out as India and Cush during the reign of Xerxes (485-465 BC).

Roman and Egyptian transatlantic voyages - In 1975 two intact amphorae were recovered from the bottom of Guanabara Bay, near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In 1981 archeologist Robert Marx discovered thousands of pottery fragments in the same locality, including 200 necks from amphorae. The amphorae have been shown to be of Roman make, from the 2nd Century BC. Also, tests done on internal tissue samples from ancient Egyptian mummies have revealed traces of chemicals only found in the Americas in antiquity, such as tobacco and coca. Because the samples taken from sundry Egyptian mummies were of internal tissues, the likelihood for contamination is smaller.

The first major step in opening the Silk Road between the East and the West came with the expansion of Alexander the Great deep into Central Asia, as far as Ferghana at the borders of the modern-day Xinjiang region of China, where he founded in 329 BC a Greek settlement in the city of Alexandria Eschate "Alexandria The Furthest", Khujand (also called Khozdent or Khojent - formerly Leninabad), in the state of Tajikistan.

When Alexander the Great's successors, the Ptolemies, took control of Egypt in 323 BC, they began to actively promote trade with Mesopotamia, India, and East Africa through their ports on the Red Sea coast, as well as overland. This was assisted by the active participation of a number of intermediaries, especially the Nabataeans and other Arabs.

The Greeks were to remain in Central Asia for the next three centuries, first through the administration of the Seleucid Empire, and then with the establishement of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in Bactria. They kept expanding eastward, especially during the reign of Euthydemus (230-200 BC), who extended his control to Sogdiana, reaching and going beyond the city of Alexandria Eschate. There are indications that he may have led expeditions as far as Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 200 BC. The Greek historian Strabo writes that "they extended their empire even as far as the Seres (China) and the Phryni".

The next step came around 130 BC, with the embassies of the Han Dynasty to Central Asia, following the reports of the ambassador Zhang Qian (who was originally sent to obtain an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiong-Nu, in vain).

The Chinese emperor Wudi became interested in developing commercial relationship with the sophisticated urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia.

The Chinese were also strongly attracted by the tall and powerful horses in the possession of the Dayuan (named "Heavenly horses"), which were of capital importance in fighting the nomadic Xiongnu. The Chinese subsequently sent numerous embassies, around ten every year, to these countries and as far as Seleucid Syria. The Chinese campaigned in Central Asia on several occasion, and direct encounters between Han troops and Roman legionnaires (probably captured or recruited as mercenaries by the Xiong Nu) are recorded, particularly in the 36 BC battle of Sogdiana (Joseph Needham, Sidney Shapiro). It has been suggested that the Chinese crossbow was transmitted to the Roman world on such occasions.

The "Silk Road" essentially came into being from the 1st century BC, following these efforts by China to consolidate a road to the Western world and India, both through direct settlements in the area of the Tarim Basin and diplomatic relations with the countries of the Dayuan, Parthians and Bactrians further west.

A maritime "Silk Route" opened up between Chinese-controlled Jiaozhi (centered in modern Vietnam, near Hanoi) probably by the first century CE. It extended, via ports on the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, all the way to Roman-controlled ports in Egypt and the Nabataean territories on the northeastern coast of the Red Sea.

In 97 CE Ban Chao crossed the Tian Shan and Pamir mountains with an army of 70,000 men in a campaign against the Xiongnu (i.e., Huns). He went as far west as the Caspian Sea and the Ukraine, reaching the territory of Parthia, where he reportedly also sent an envoy named Gan Ying to Daqin (i.e., Rome). Gan Ying detailed an account of the western countries; although he likely reached only the Black Sea before turning back.

The Chinese army made an alliance with the Parthians and established some forts at a distance of a few days march from the Parthian capital Ctesiphon, planning to hold the region for several years.

Soon after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, regular communications and trade between China, Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe blossomed on an unprecedented scale. The eastern trade routes from the earlier Hellenistic powers and the Arabs that were part of the Silk Road were inherited by the Roman Empire. With control of these trade routes, citizens of the Roman Empire would receive new luxuries and greater prosperity for the Empire as a whole.

The Greco-Roman trade with India started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BC continued to increase, and according to Strabo (II.5.12), by the time of Augustus, up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos in Roman Egypt to India.

The Roman Empire connected with the Central Asian Silk Road through their ports in Barygaza (known today as Bharuch) and Barbaricum (known today as the cities of Karachi, Sindh, and Pakistan) and continued along the western coast of India.[27] An ancient "travel guide" to this Indian Ocean trade route was the Greek Periplus of the Erythraean Sea written in 60 CE.

The traveling party of Ma‘s Titianus penetrated farthest east along the Silk Road from the Mediterranean world, probably with the aim of regularizing contacts and reducing the role of middlemen, during one of the lulls in Rome's intermittent wars with Parthia, which repeatedly obstructed movement along the Silk Road. Intercontinental trade and communication became regular, organized, and protected by the 'Great Powers.' Intense trade with the Roman Empire soon followed, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians), even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees.

This belief was affirmed by Seneca the Younger in his Phaedra and by Virgil in his Georgics. Notably, Pliny the Elder knew better. Speaking of the bombyx or silk moth, he wrote in his Natural Histories "They weave webs, like spiders, that become a luxurious clothing material for women, called silk."[28] The Romans traded spices, perfumes, and silk.

Roman artisans began to replace yarn with valuable plain silk cloths from China. Chinese wealth grew as they delivered silk and other luxury goods to the Roman Empire, whose wealthy Roman women admired their beauty. The Roman Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the importation of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral.

The Roman Empire, and its demand for sophisticated Asian products, crumbled in the West around the 5th century. The unification of Central Asia and Northern India within Kushan Empire in the 1st to 3rd centuries reinforced the role of the powerful merchants from Bactria and Taxila. They fostered multi-cultural interaction as indicated by their 2nd century treasure hoards filled with products from the Greco-Roman world, China, and India, such as in the archeological site of Begram.

The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE.Central Asian commercial & cultural exchanges - Notably, the Buddhist faith and the Greco-Buddhist culture started to travel eastward along the Silk Road, penetrating in China from around the 1st century BC.

The Kushan empire, in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, was located at the center of these exchanges. They fostered multi-cultural interaction as indicated by their 2nd century treasure hoards filled with products from the Greco-Roman world, China and India, such as in the archeological site of Begram.

The heyday of the Silk Road corresponds to that of the Byzantine Empire in its west end, Sasanid Period to Il Khanate Period in the Nile-Oxus section and Three Kingdoms to Yuan Dynasty in the Sinitic zone in its east end. Trade between East and West also developed on the sea, between Alexandria in Egypt and Guangzhou in China, fostering the expansion of Roman trading posts in India.

Historians also talk of a "Porcelain Route" or "Silk Route" across the Indian Ocean. The Silk Road represents an early phenomenon of political and cultural integration due to inter-regional trade. In its heyday, the Silk Road sustained an international culture that strung together groups as diverse as the Magyars, Armenians, and Chinese.

Under its strong integrating dynamics on the one hand and the impacts of change it transmitted on the other, tribal societies previously living in isolation along the Silk Road or pastoralists who were of barbarian cultural development were drawn to the riches and opportunities of the civilizations connected by the Silk Road, taking on the trades of marauders or mercenaries. Many barbarian tribes became skilled warriors able to conquer rich cities and fertile lands, and forge strong military empires.

The Silk Road gave rise to the clusters of military states of nomadic origins in North China, invited the Nestorian, Manichaean, Buddhist, and later Islamic religions into Central Asia and China, created the influential Khazar Federation and at the end of its glory, brought about the largest continental empire ever: the Mongol Empire, with its political centers strung along the Silk Road (Beijing in North China, Karakorum in central Mongolia, Sarmakhand in Transoxiana, Tabriz in Northern Iran, Astrakhan in lower Volga, Bahcesaray in Crimea, Kazan in Central Russia, Erzurum in eastern Anatolia), realizing the political unification of zones previously loosely and intermittently connected by material and cultural goods.

The Roman empire, and its demand for sophisticated Asian products, crumbled in the West around the 5th century. In Central Asia, Islam expanded from the 7th century onward, bringing a stop to Chinese westward expansion at the Battle of Talas in 751 CE.

Further expansion of the Islamic Turks in Central Asia from the 10th century finished disrupting trade in that part of the world, and Buddhism almost disappeared.

Artistic transmission on the Silk Road - Buddhist deities - The image of the Buddha, originating during the 1st century CE in northern India (areas of Gandhara and Mathura) was transmitted progressively through Central Asia and China until it reached Japan in the 6th century CE. However the transmission of many iconographical details is clear, such as the Hercules inspiration behind the Nio guardian deities in front of Japanese Buddhist temples, and also representations of the Buddha reminiscent of Greek art such as the Buddha in Kamakura.

Another Buddhist deity, Shukongoshin, is also an interesting case of transmission of the image of the famous Greek god Herakles to the Far-East along the Silk Road. Herakles was used in Greco-Buddhist art to represent Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha, and his representation was then used in China and Japan to depict the protector gods of Buddhist temples.

The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE.

Wind god - Various other artistic influences from the Silk Road can be found in Asia, one of the most striking being that of the Greek Wind God Boreas, transiting through Central Asia and China to become the Japanese Shinto wind god Fujin.

Floral scroll pattern - Finally the Greek artistic motif of the floral scroll was transmitted from the Hellenistic world to the area of the Tarim Basin around the 2nd century CE, as seen in Serindian art and wooden architectural remains. It then was adopted by China between the 4th and 6th centuries CE and displayed on tiles and ceramics; then it transmitted to Japan in the form of roof tile decorations of Japanese Buddhist temples circa 7th century CE, particularly in Nara temple building tiles, some of them exactly depicting vines and grapes.

The Mongol expansion throughout the Asian continent from around 1215 to 1360 helped bring political stability and re-establish the Silk Road. In the late 13th century, a Venetian explorer named Marco Polo became one of the first Europeans to travel the Silk Road to China. Westerners became more aware of the Far East when Polo documented his travels in Il Milione.

He was followed by numerous Christian missionaries to the East, such as William of Rubruck, Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, Andrew of Longjumeau, Odoric of Pordenone, Giovanni de Marignolli, Giovanni di Monte Corvino, and other travellers such as Ibn Battuta or Niccolo Da Conti. Luxury goods were traded from one middleman to another, from China to the West, resulting in high prices for the trade goods.

Technological transfer to the West - Many technological innovations from the East seem to have filtered into Europe around that time. The period of the High Middle Ages in Europe saw major technological advances, including the adoption through the Silk Road of printing, gunpowder, the astrolabe, and the compass, in many ways sustaining the development of Renaissance Europe and the Age of Exploration.

Chinese maps such as the Kangnido and islamic mapmaking seem to have influenced the emergence of the first practical world maps, such as those of De Virga or Fra Mauro. Ramusio, a contemporary, states that Fra Mauro's map is "an improved copy of the one brought from Cathay by Marco Polo".Large Chinese junks were also observed by these travelers and may have provided impetus to develop larger ships in Europe. ships were also observed.

However, with the disintegration of the Mongol Empire also came discontinuation of the Silk Road's political, cultural and economic unity. Turkmeni marching lords seized the western end of the Silk Road - the decaying Byzantine Empire. After the Mongol Empire, the great political powers along the Silk Road became economically and culturally separated. Accompanying the crystallization of regional states was the decline of nomad power, partly due to the devastation of the Black Death and partly due to the encroachment of sedentary civilizations equipped with gunpowder.

The effect of gunpowder and early modernity on Europe was the integration of territorial states and increasing mercantilism; whereas on the Silk Road, gunpowder and early modernity had the opposite impact: the level of integration of the Mongol Empire could not be maintained, and trade declined (though partly due to an increase in European maritime exchanges).

The Silk Road stopped serving as a shipping route for silk around 1400.

The great explorers: Europe reaching for Asia - The disappearance of the Silk Road following the end of the Mongols was one of the main factors that stimulated the Europeans to reach the prosperous Chinese empire through another route, especially by the sea. Tremendous profits were to be obtained for anyone who could achieve a direct trade connection with Asia.

When he went West in 1492, Christopher Columbus reportedly wished to create yet another Silk Route to China. It was allegedly one of the great disappointments of western nations to have found a continent "in-between" before recognizing the potential of a "New World."

The wish to trade directly with China was also the main drive behind the expansion of the Portuguese beyond Africa after 1480, followed by the powers of the Netherlands and Great Britain from the 17th century.

As late as the 18th century, China was usually still considered the most prosperous and sophisticated of any civilization on Earth.

Silk Road Wikipedia

Major corridor of Silk Road already home to high-mountain herders over 4,000 years ago PhysOrg - November 2, 2018

Long before the formal creation of the Silk Road - a complex system of trade routes linking East and West Eurasia through its arid continental interior - pastoral herders living in the mountains of Central Asia helped form new cultural and biological links across this region. However, in many of the most important channels of the Silk Road itself, including Kyrgyzstan's Alay Valley, a large mountain corridor linking northwest China with the oasis cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, very little is known about the lifestyles of early people who lived there in the centuries and millennia preceding the Silk Road era.

1,700-Year-Old Silk Road Cemetery Contains Mythical Carvings Live Science - November 24, 2014

A cemetery dating back roughly 1,700 years has been discovered along part of the Silk Road, a series of ancient trade routes that once connected China to the Roman Empire. The cemetery was found in the city of Kucha, which is located in present-day northwest China. Ten tombs were excavated, seven of which turned out to be large brick structures. One tomb, dubbed "M3," contained carvings of several mythical creatures, including four that represent different seasons and parts of the heavens: the White Tiger of the West, the Vermilion Bird of the South, the Black Turtle of the North and the Azure Dragon of the East.

Shepherds Spread Grain Along Silk Road 5,000 Years Ago Live Science - April 4, 2014

Nearly 5,000 years ago, nomadic shepherds opened some of the first links between eastern and western Asia. Archaeologists recently discovered domesticated crops from opposite sides of the continent mingled together in ancient herders' campsites found in the rugged grasslands and mountains of central Asia. Ancient wheat and broomcorn millet, recovered in nomadic campsites in Kazakhstan, show that prehistoric herders in Central Eurasia had incorporated both regional crops into their economy and rituals nearly 5,000 years ago.

Ancient Tombs Discovered Along Silk Road Live Science - February 6, 2013

Along the ancient trade route known as the Silk Road, archaeologists have unearthed 102 tombs dating back some 1,300 years - and almost half of the tombs were for infants. The surprising discovery was made in remote western China, where construction workers digging for a hydroelectric project found the cluster of tombs. Each tomb contains wooden caskets covered in felt, inside of which are desiccated human remains, as well as copper trinkets, pottery and other items buried as sacrificial items.

The tombs, which date back to the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907), also contain a number of well-preserved utensils made from gourds, some of which were placed inside the wooden caskets. But why so many of the tombs are for infants remains a mystery. Further research is needed to determine why so many people from that tribe died young. The area where the tombs were found, the Kezilesu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture, was an important mountain pass along the Silk Road, a network of ancient trading routes that connected the Far East with Europe.