The Roman military was intertwined with the Roman state much more closely than in a modern European nation. Josephus describes the Roman people being as if they were "born ready armed." and the Romans were for long periods prepared to engage in almost continuous warfare, absorbing massive losses. For a large part of Rome's history, the Roman state existed as an entity almost solely to support and finance the Roman military.

The military's campaign history stretched over 1300 years and saw Roman armies campaigning as far East as Parthia (modern-day Iran), as far south as Africa (modern-day Tunisia) and Aegyptus (modern-day Egypt) and as far north as Britannia (modern-day England, Scotland, and Northeast Wales).

The makeup of the Roman military changed substantially over its history, from its early history as an unsalaried citizen militia to a later professional force. The equipment used by the military altered greatly in type over time, though there were very few technological improvements in weapons manufacture, in common with the rest of the classical world. For much of its history, the vast majority of Rome's forces were maintained at or beyond the limits of its territory, in order to either expand Rome's domain, or protect its existing borders.

At its territorial height, the Roman Empire may have contained between 45 million and 120 million people. Historian Edward Gibbon estimated that the size of the Roman army "most probably formed a standing force of 3,750,000" men at the Empire's territorial peak in the time of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. This estimate probably included only legionary and auxiliary troops of the Roman army.

There is no archaeological evidence that suggests that women constituted a significant proportion of troops even amongst the federated troops of the late empire. For the majority of its history, the Roman army was open to male recruits only, and for a greater part of that history only those classified as Roman citizens (as opposed to allies, provincials, freedmen and slaves) were eligible for military service.

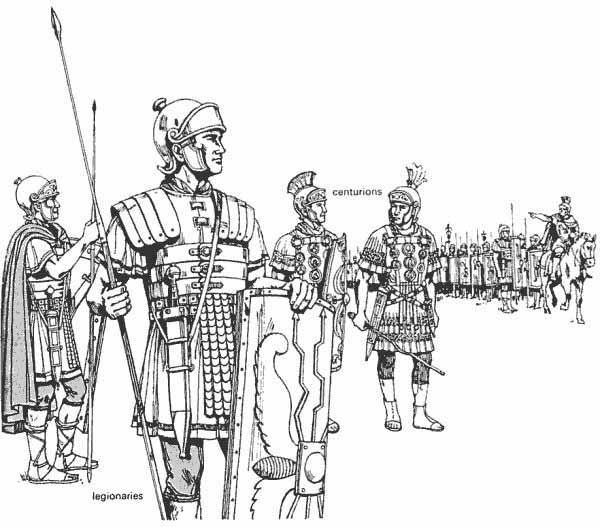

Initially, Rome's military consisted of an annual citizen levy performing military service as part of their duty to the state. During this period, the Roman army would prosecute seasonal campaigns against largely local adversaries. As the extent of the territories falling under Roman suzerainty expanded, and the size of the city's forces increased, the soldiery of ancient Rome became increasingly professional and salaried. As a consequence, military service at the lower (non-staff) levels became progressively longer-term. Roman military units of the period were largely homogeneous and highly regulated. The army consisted of units of citizen infantry known as legions (Latin: legiones) as well as non-legionary allied troops known as auxilia. The latter were most commonly called upon to provide light infantry or cavalry support.

Military service in the later empire continued to be salaried and professional for Rome's regular troops. However, the trend of employing allied or mercenary troops was expanded such that these troops came to represent a substantial proportion of Rome's forces. At the same time, the uniformity of structure found in Rome's earlier military forces disappeared. Soldiery of the era ranged from lightly armed mounted archers to heavy infantry, in regiments of varying size and quality. This was accompanied by a trend in the late empire of an increasing predominance of cavalry rather than infantry troops, as well as a requital of more mobile operations.

In the legions of the Republic, discipline was fierce and training harsh, all intended to instill a group cohesion or esprit de corps that could bind the men together into effective fighting units. Unlike opponents such as the Gauls, who were fierce individual warriors, Roman military training concentrated on instilling teamwork and maintaining a level head over individual bravery - troops were to maintain exact formations in battle and "despise wild swinging blows" in favor of sheltering behind one's shield and delivering efficient stabs when an opponent made himself vulnerable.

Loyalty was to the Roman state but pride was based in the soldier's unit, to which was attached a military standard - in the case of the legions a legionary eagle. Successful units were awarded with accolades that became part of their official name, such as the 20th legion, which became the XX Valeria Victrix (the "Valiant and Victorious 20th").

Of the martial culture of less valued units such as sailors, and light infantry, less is known, but it is doubtful that its training was as intense or its esprit de corps as strong as in the legions.

Although early in its history troops were expected to provide much of their own equipment, eventually the Roman military was almost entirely funded by the state. Since soldiers of the early Republican armies were also unpaid citizens, the financial burden of the army on the state was minimal. However, since the Roman state did not provide services such as housing, health, education, social security and public transport that are part and parcel of modern states, the military always represented by far the greatest expenditure of the state.

During the time of expansion in the Republic and early Empire, Roman armies had acted as a source of revenue for the Roman state, plundering conquered territories, displaying the massive wealth in triumphs upon their return and fueling the economy to the extent that historians such as Toynbee and Burke believe that the Roman economy was essentially a plunder economy.

However, after the Empire had stopped expanding in the 2nd century, this source of revenue dried up; by the end of the 3rd century, Rome had "ceased to vanquish." As tax revenue was plagued by corruption and hyperinflation during the Crisis of the Third Century, military expenditures began to become a "crushing burden" on the finances of the Roman state. It now highlighted weaknesses that earlier expansion had disguised. By 440, an imperial law frankly states that the Roman state has insufficient tax revenue to fund an army of a size required by the demands placed upon it.

Several additional factors bloated the military expenditure of the Roman Empire. Firstly, substantial rewards were paid for the demeanor of "barbarian" chieftains in the form of negotiated subsidies and for the provision of allied troops. Secondly, the military boosted its numbers, possibly by one third in a single century. Finally, the military increasingly relied on a higher ratio of cavalry units in the late Empire, which were many times more expensive to maintain than infantry units.

While military size and costs increased, new taxes were introduced or existing tax laws reformed in the late Empire in order to finance it frequently. Although more inhabitants were available within the borders of the late Empire, reducing the per capita costs for an increased standing army was impractical. A large number of the population could not be taxed because they were slaves or held Roman citizenship, which exempted them from taxation in one way or another. Of the remaining, a large number were already impoverished by centuries of warfare and weakened by chronic malnutrition. Still, they had to handle an increasing tax rate and so they often abandoned their lands to survive in a city.

Of the Western Empire's taxable population, a larger number than in the East could not be taxed because they were "primitive subsistence peasants" and did not produce a great deal of goods beyond agricultural products. Plunder was still made from suppressing insurgencies within the Empire and on limited incursions into enemy land. Legally, much of it should have returned to the Imperial purse, but these goods were simply kept by the common soldiers, who demanded it of their commanders as a right. Given the low wages and high inflation in the later Empire, the soldiers felt that they had a right to acquire plunder.

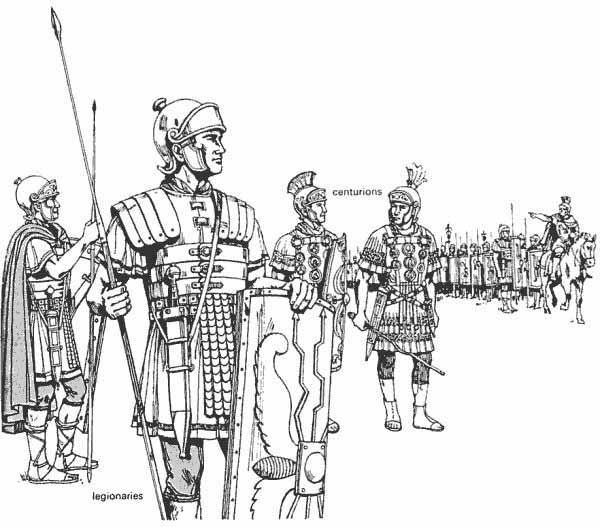

Locations of Roman legions, 80 AD

The military capability of Ancient Rome - its military preparedness or readiness - was always primarily based upon the maintenance of an active fighting force acting either at or beyond its military frontiers, something that historian Luttwak refers to as a "thin linear perimeter." This is best illustrated by showing the dispositions of the Roman legions, the backbone of the Roman army. (see right). Because of these deployments, the Roman military did not keep a central strategic reserve after the Social War. Such reserves were only re-established during the late Empire, when the army was split into a border defense force and mobile response field units.

The Roman military was keen on the doctrine of power projection - it frequently removed foreign rulers by force or intimidation and replaced them with puppets. This was facilitated by the maintenance, for at least part of its history, of a series of client states and other subjugate and buffer entities beyond its official borders, although over which Rome extended massive political and military control. On the other hand, this also could mean the payment of immense subsidies to foreign powers and opened the possibility of extortion in case military means were insufficient.

The Empire's system of building an extensive and well-maintained road network, as well as its absolute command of the Mediterranean for much of its history, enabled a primitive form of rapid reaction, also stressed in modern military doctrine, although because there was no real strategic reserve, this often entailed the raising of fresh troops or the withdrawing of troops from other parts of the border. However, border troops were usually very capable of handling enemies before they could penetrate far into the Roman hinterland.

The Roman military had an extensive logistical supply chain. There was no specialized branch of the military devoted to logistics and transportation, although this was to a great extent carried out by the Roman Navy due to the ease and low costs of transporting goods via sea and river compared to over land.

There is archaeological evidence that Roman armies campaigning in Germania were supplied by a logistical supply chain beginning in Italy and Gaul, then transported by sea to the northern coast of Germania, and finally penetrating into Germania via barges on inland waterways. Forces were routinely supplied via fixed supply chains, and although Roman armies in enemy territory would often supplement or replace this with foraging for food or purchasing food locally, this was often insufficient for their needs: Heather states that a single legion would have required 13.5 tonnes of food per month, and that it would have proved impossible to source this locally.

For the most part, Roman cities had a civil guard used for maintaining the peace. Due to fears over rebellions and other uprisings, they were forbidden to be armed up to militia levels. Policing was split between the civil guard for low-level affairs and the Roman legions and auxilia for suppressing higher-level rioting and rebellion. This created a limited strategic reserve, one that fared poorly in actual warfare.

The massive earthen ramp at Masada, designed by the Roman army to breach the fortress' walls

The military engineering of Ancient Rome's armed forces was of a scale and frequency far beyond that of any of its contemporaries. Indeed, military engineering was in many ways institutionally endemic in Roman military culture, as demonstrated by the fact that each Roman legionary had as part of his equipment a shovel, alongside his gladius (sword) and pila (spears). Heather writes that "Learning to build, and build quickly, was a standard element of training".

This engineering prowess was, however, only evident during the peak of Roman military prowess under the mid-Republic to the mid-Empire. Prior to the mid-Republic period there is little evidence of protracted or exceptional military engineering, and in the late Empire likewise there is little sign of the kind of engineering feats that were regularly carried out in the earlier Empire.

Roman military engineering took both routine and extraordinary forms, the former a proactive part of standard military procedure, and the latter of an extraordinary or reactionary nature. Proactive military engineering took the form of the regular construction of fortified camps, in road-building, and in the construction of siege engines. The knowledge and experience learned through such routine engineering lent itself readily to any extraordinary engineering projects required by the army, such as the circumvallations constructed at Alesia and the earthen ramp constructed at Masada.

This engineering expertise practiced in daily routines also served in the construction of siege equipment such as ballistae, onagers and siege towers, as well as allowing the troops to construct roads, bridges and fortified camps. All of these led to strategic capabilities, allowing Roman troops to, respectively, assault besieged settlements, move more rapidly to wherever they were needed, cross rivers to reduce march times and surprise enemies, and to camp in relative security even in enemy territory.

Rome was established as a nation making aggressive use of its high military potential. From very early on in its history it would raise two armies annually to campaign abroad. Far from the Roman military being solely a defence force, for much of its history, it was a tool of aggressive expansion.

Notably, the Roman army had derived from a militia of mainly farmers, and gaining new farming lands for the growing population or later retiring soldiers was often one of the campaigns' chief objectives. Only in the late Empire did the Roman military's primary role become the preservation of control over its territories. Remaining major powers next to Rome were the Kingdom of Aksum, Parthia and the Hunnic Empire. Knowledge of China, the Han Dynasty at the times of Mani, existed and it is believed that Rome and China swapped embassies in about 170.

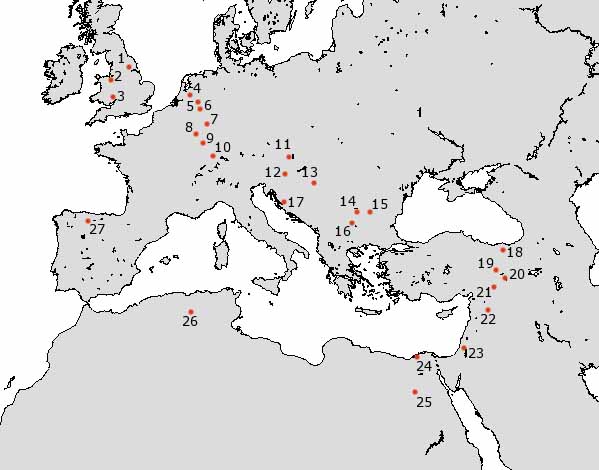

The strategy of the Roman military contains its grand strategy (the arrangements made by the state to implement its political goals through a selection of military goals, a process of diplomacy backed by threat of military action, and a dedication to the military of part of its production and resources), operational strategy (the coordination and combination of the military forces and their tactics for the goals of an overarching strategy) and, on a small scale, its military tactics (methods for military engagement in order to defeat the enemy).

If a fourth rung of "engagement" is added, then the whole can be seen as a ladder, with each level from the foot upwards representing a decreasing concentration on military engagement. Whereas the purest form of tactics or engagement are those free of political imperative, the purest form of political policy does not involve military engagement. Strategy as a whole is the connection between political policy and the use of force to achieve it.

In its clearest form, strategy deals solely with military issues: either a threat or an opportunity is recognized, an evaluation is made, and a military stratagem for meeting it is devised. However, as Clausewitz stated, a successful military strategy may be a means to an end, but it is not an end in itself. Where a state has a long term political goal to which they apply military methods and the resources of the state, that state can be said to have a grand strategy.

To an extent, all states will have a grand strategy to a certain degree even if it is simply determining which forces to raise as a military, or how to arm them. Whilst early Rome did raise and arm troops, they tended to raise them annually in response to the specific demands of the state during that year. Such a reactive policy, whilst possibly more efficient than the maintenance of a standing army, does not indicate the close ties between long-term political goals and military organization demanded by grand strategy

Early indications for a Roman grand strategy emerged during the three Punic wars with Carthage, in which Rome was able to influence the course of the war by selecting to ignore the armies of Hannibal threatening its homeland and to invade Africa instead in order to dictate the primary theatre of war

In the Empire, as the need for and size of the professional army grew, the possibility arose for the expansion of the concept of a grand strategy to encompass the management of the resources of the entire Roman state in the conduct of warfare: great consideration was given in the Empire to diplomacy and the use of the military to achieve political goals, both through warfare and also as a deterrent. The contribution of actual (rather than potential) military force to strategy was largely reduced to operational strategy - the planning and control of large military units. Rome's grand strategy incorporated diplomacy through which Rome might forge alliances or pressure another nation into compliance, as well as the management of the post-war peace.

When a campaign did go badly wrong, operational strategy varied greatly as the circumstances dictated, from naval actions to sieges, assaults of fortified positions and open battle. However, the preponderance of Roman campaigns exhibit a preference for direct engagement in open battle and, where necessary, the overcoming of fortified positions via military engineering. The Roman army was adept at building fortified camps for protection from enemy attack, but history shows a reluctance to sit in the camp awaiting battle and a history of seeking open battle.

In the same way that Roman tactical maneuver was measured and cautious, so too was their actual engagement of the enemy. The soldiers were long-term service professionals whose interest lay in receiving a large pension and an allocation of land on retirement from the army, rather than in seeking glory on the battlefield as a warrior. The tactics of engagement largely reflected this, concentrating on maintaining formation order and protecting individual troops rather than pushing aggressively to destroy the maximum number of enemy troops in a wild charge.

A battle usually opened with light troops skirmishing with the opposition. These light forces then withdrew to the flanks or between the gaps in the central line of heavy infantry. Cavalry might be launched against their opposing numbers or used to screen the central core from envelopment. As the gap between the contenders closed, the heavy infantry typically took the initiative, attacking on the double. The front ranks usually cast their pila, and the following ranks hurled theirs over the heads of the front-line fighters. If a cast pilum did not cause direct death or injury, they were so designed that the hard iron triangular points would stick into enemy shields, bending on their soft metal shafts, weighing down the shields and making them unusable.

After the pila were cast, the soldiers then drew their swords and engaged the enemy. However, rather than charging as might be assumed, great emphasis was placed on the protection gained from sheltering behind the scutum and remaining unexposed, stabbing out from behind the protection of the shield whenever an exposed enemy presented himself. Fresh troops were fed in from the rear, through the "checkboard" arrangement, to relieve the injured and exhausted further ahead.

Many Roman battles, especially during the late empire, were fought with the preparatory bombardment from Ballistas and Onagers. These war machines, a form of ancient artillery, launched arrows and large stones towards the enemy, proving most effective against close-order formations and structures.

Initially, Rome's military consisted of an annual citizen levy performing military service as part of their duty to the state. During this period, the Roman army would prosecute seasonal campaigns against its tribal neighbors and Etruscan towns within Italy. As the extent of the territories falling under Roman suzerainty expanded, and the size of the city's forces increased, the soldiery of ancient Rome became increasingly professional and salaried.

As a consequence, military service at the lower (non-staff) levels became progressively longer-term. Roman military units of the period were largely homogeneous and highly regulated. The army consisted of units of citizen infantry known as legions (Latin: legiones) as well as non-legionary allied troops known as auxilia. The latter were most commonly called upon to provide light infantry or cavalry support.

Rome's forces came to dominate much of the Mediterranean and further afield, including the provinces of Britannia and Asia at the Empire's height. They were tasked with manning and securing the borders of the provinces brought under Roman control, as well as Italy itself. Strategic-scale threats were generally less serious in this period, and strategic emphasis was placed on preserving gained territory. The army underwent changes in response to these new needs and became more dependent on fixed garrisons than on march-camps and continuous field operations.

In the late Empire, military service continued to be salaried and professional for Rome's regular troops. However, the trend of employing allied or mercenary troops was expanded such that these troops came to represent a substantial proportion of Rome's forces. At the same time, the uniformity of structure found in Rome's earlier military forces disappeared. Soldiery of the era ranged from lightly armed mounted archers to heavy infantry, in regiments of varying size and quality. This was accompanied by a trend in the late empire of an increasing predominance of cavalry rather than infantry troops, as well as a requital of more mobile operations.

Although Roman iron-working was enhanced by a process known as carburization, the Romans are not thought to have developed true steel production. From the earliest history of the Roman state to its downfall, Roman arms were therefore uniformly produced from either bronze or, later, iron. As a result the 1300 years of Roman military technology saw little radical change in technological level. Within the bounds of classical military technology, however, Roman arms and armor was developed, discarded, and adopted from other peoples based on changing methods of engagement. It included at various times stabbing daggers and swords, stabbing or thrusting swords, long thrusting spears or pikes, lances, light throwing javelins and darts, slings, and bow and arrows.

Roman military personal equipment was produced in large numbers to established patterns and used in an established way. It therefore varied little in design and quality within each historical period. According to Hugh Elton, Roman equipment (especially armor) gave them "a distinct advantage over their barbarian enemies." who were often, as Germanic tribesmen, completely unarmoured. However, Luttwak points out that whilst the uniform possession of armour gave Rome an advantage, the actual standard of each item of Roman equipment was of no better quality than that used by the majority of its adversaries. The relatively low quality of Roman weaponry was primarily a function of its large-scale production, and later factors such as governmental price fixing for certain items, which gave no allowance for quality, and incentivised cheap, poor-quality goods.

The Roman military readily adopted types of arms and armor that were effectively used against them by their enemies. Initially Roman troops were armed after Greek and Etruscan models, using large oval shields and long pikes. On encountering the Celts they adopted much Celtic equipment and again later adopted items such as the gladius from Iberian peoples. Later in Rome's history, it adopted practices such as arming its cavalry with bows in the Parthian style, and even experimented briefly with niche weaponry such as elephants and camel-troops.

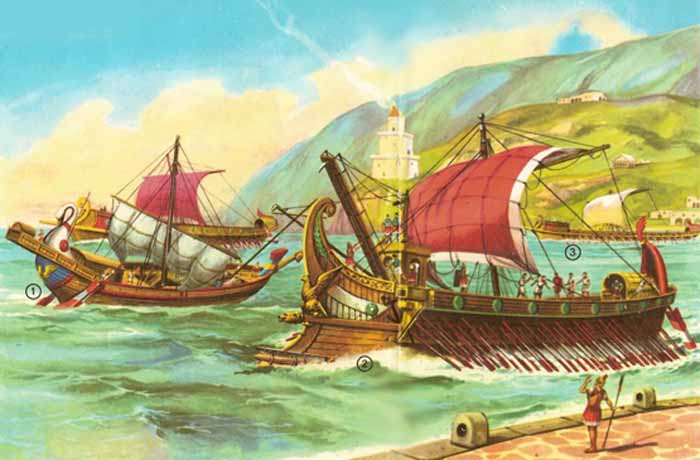

Besides personal weaponry, the Roman military adopted team weaponry such as the ballista and developed a naval weapon known as the corvus, a spiked plank used for affixing and boarding enemy ships.

The Roman army is the generic term for the terrestrial armed forces deployed by the kingdom of Rome (to ca. 500 BC), the Roman Republic (500-31 BC), the Roman Empire (31 BC - AD 476) and its successor, the Byzantine empire (476-1453). It is thus a term that spans approximately 2,000 years, during which the Roman armed forces underwent numerous permutations in composition, organization, equipment and tactics, while conserving a core of lasting traditions.

"Roman Army" is the name given by English-speakers to the soldiers and other military forces who served the Roman Kingdom, the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. The Roman words for the military in general were based on the word for one soldier, miles. The army in general was the militia, and a commander of military operations, militiae magister. In the republic, a general might be called imperator, "commander" (as in Caesar imperator), but under the empire, that term became reserved for the highest office.

The Romans only called themselves "Roman" in very formal circumstances, such as senatus populusque Romanus (SPQR), "the Roman senate and people" or when they needed to distinguish themselves from others, as in civis Romanus, "Roman citizen." Otherwise, they used less formal and egocentric terms, such as mare nostrum, "our sea" (the Mediterranean) or nostri, "our men." The state was res publica, "the public thing", and parallel to it was res militaris, "the military thing", which could have a number of connotations.

-

The development of the Roman army may be divided into the following 8 broad historical phases:

(1) The Early Roman army of the Roman kingdom and of the early republic (to ca. 300 BC). During this period, when warfare chiefly consisted of small-scale plundering-raids, it has been suggested that the Roman army followed Etruscan or Greek models of organization and equipment. The early Roman army was based on an annual levy or conscription of citizens for a single campaigning-season, hence the term legion for the basic Roman military unit (derived from legere, "to levy").

(2) The Roman army of the mid-Republic (a.k.a. as the "manipular army" or the "Polybian army" after the Greek historian Polybius, who provides the most detailed extant description of this phase) of the mid-Republican period (ca. 300-107 BC).

During this period, the Romans, while maintaining the levy system, adopted the Samnite manipular organization for their legions and also bound all the other peninsular Italian states into a permanent military alliance (see Socii). The latter were required to supply (collectively) roughly the same number of troops to joint forces as the Romans to serve under Roman command. Legions in this phase were always accompanied on campaign by the same number of allied alae, units of roughly the same size as legions.

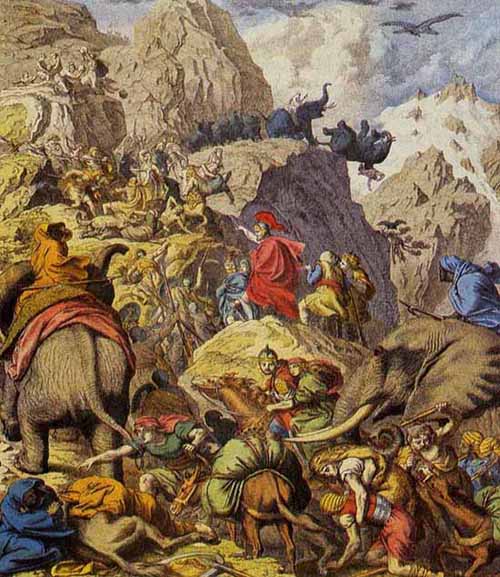

Punic Wars

After the 2nd Punic War (218-201 BC), the Romans acquired an overseas empire, which necessitated standing forces to fight lengthy wars of conquest and garrison the newly gained provinces. Thus the army's character mutated from a temporary force based entirely on short-term conscription to a standing army in which the conscripts were complemented by a large number of volunteers who were willing to serve for much longer than the legal 6-year limit.

These volunteers were mainly from the poorest social class, who did not have plots to tend at home and were attracted by the modest military pay and the prospect of a share of war-booty. The minimum property requirement for service in the legions, which had been suspended during the 2nd Punic War, was effectively ignored from 201 BC onwards in order to recruit sufficient volunteers. Also during this period, the manipular structure was gradually phased out, and the much larger cohort became the main tactical unit. In addition, from the 2nd Punic War onwards, Roman armies were always accompanied by units of non-Italian mercenaries, Numidian light cavalry, Cretan archers, and Balearic slingers, who provided specialist functions that Roman armies had previously lacked.

(3) The Roman army of the Late Republic (107-30 BC) marks the continued transition between the conscription-based citizen-levy of the mid-Republic and the mainly volunteer, professional standing forces of the imperial era. The main literary source for the army's organization and tactics in this phase are the works of Julius Caesar, the most notable of a series of warlords who contested power in this period. As a result of the Social War (91-88 BC), all Italians were granted Roman citizenship, the old allied alae were abolished and their members integrated into the legions.

Regular annual conscription remained in force and continued to provide the core of legionary recruitment, but an ever-increasing proportion of recruits were volunteers, who signed up for 16-year terms as opposed to the maximum 6 years for conscripts. The loss of ala cavalry reduced Roman/Italian cavalry by 75%, and legions became dependent on allied native horse for cavalry cover. This period saw the large-scale expansion of native forces employed to complement the legions, made up of numeri (units) recruited from tribes within Rome's overseas empire and neighbouring allied tribes. Large numbers of heavy infantry and cavalry were recruited in Spain, Gaul and Thrace, and archers in Thrace, Anatolia and Syria. However, these native units were not integrated with the legions, but retained their own traditional leadership, organization, armor and weapons.

(4) The Imperial Roman army (30 BC - AD 284), when the Republican system of citizen-conscription was replaced by a standing professional army of mainly volunteers serving standard 20-year terms (plus 5 as reservists), as established by the first Roman emperor, Augustus (sole ruler 30 BC - AD 14).

The legions, consisting almost entirely of heavy infantry, numbered 25 of ca. 5,000 men each (total 125,000) under Augustus, increasing to a peak of 33 of 5,500 (ca. 180,000 men) by AD 200 under Septimius Severus. Legions continued to recruit Roman citizens only i.e. mainly the inhabitants of Italy and Roman colonies until AD 212.

Regular annual conscription of citizens was abandoned and only decreed in emergencies (e.g. during the Illyrian revolt AD 6-9). Legions were now flanked by the auxilia, a corps of regular troops recruited mainly from peregrini, imperial subjects who did not hold Roman citizenship (the great majority of the empire's inhabitants until 212, when all were granted citizenship).

Auxiliaries, who served a minimum term of 25 years, were also mainly volunteers, but regular conscription of peregrini was employed for most of the 1st century AD. The auxilia consisted, under Augustus, of ca. 250 regiments of roughly cohort size i.e. ca. 500 men (125,000 men, or 50% of total army effectives). The number of regiments increased to ca. 400 under Severus, of which ca. 13% were double-strength (ca. 250,000 men, or 60% of total army). Auxilia contained heavy infantry equipped similarly to legionaries; and almost all the army's cavalry (both armoured and light), and archers and slingers.

(5) The Late Roman army (284-476 and its continuation, in the surviving eastern half of the empire, as the East Roman army to 641). In this phase, crystalized by the reforms of the emperor Diocletian (ruled 284-305), the Roman army returned to regular annual conscription of citizens, while admitting large numbers of non-citizen barbarian volunteers. However, soldiers remained 25-year professionals and did not return to the short-term levies of the Republic. The old dual organization of legions and auxilia was abandoned, with citizens and non-citizens now serving in the same units. The old legions were broken up into cohort or even smaller sizes. At the same time, a substantial proportion of the army's effectives were stationed in the interior of the empire, in the form of comitatus praesentales, armies that escorted the emperors.

(6) The Middle Byzantine army (641-1081), is the army of the Byzantine state in its classical form (i.e. after the permanent loss of its Near Eastern and North African territories to the Arab conquests after 641). This army was based on conscription of professional troops in the themes structure characteristic of this period, and from ca. 950 on the professional troops known as tagmata.

(7) The Komnenian Byzantine army, named after the Komnenos dynasty, which ruled in 1081-1185. This was an army built virtually from scratch after the permanent loss of Byzantium's traditional main recruiting ground of Anatolia to the Turks following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and the destruction of the last regiments of the old army in the wars against the Normans in the early 1080s. It survived until the fall of Constantinople to the Western crusaders in 1204. This army was characterised by a large number of mercenary regiments composed of troops of foreign origin such as the Varangian Guard, and the introduction of the pronoia system.

(8) The Palaiologan Byzantine army, named after the Palaiologos dynasty (1261-1453), which ruled Byzantium between the recovery of Constantinople from the Crusaders and its fall to the Turks in 1453. Initially, it continued some practices inherited from the Komnenian era and retained a strong native element until the late 13th century. During the last century of its existence however, the empire was little more than a city-state that hired foreign mercenary bands for its defence. Thus the Byzantine army finally lost any meaningful connection with the standing imperial Roman army.

Rome was probably founded as a compromise between Etruscan residents of the area and Italic tribes nearby. The kings were Etruscan. Their language was still spoken by noble families in the early empire, although sources tell us it was dying out. Under the first king, Romulus, society consisted of gentes, or clans, arranged in 80 curiae and three tribes. From them were selected 8000 pedites (infantry) and 800 celeres (cavalry) of gentes-connected men. The decimal scheme seems already to have been in existence: one unit of fast troops for every 10 of foot.At first, under the Etruscan Kings, the massive Greek phalanx was the most desired battle formation. Early Roman soldiers hence must have looked much like Greek hoplites.

A key moment in Roman history was the introduction of the census (the counting of the people) under Servius Tullius. He had found that the aristocratic organization now did not provide enough men for defense against the hill tribes (Samnites and others). Consequently, he accepted non-aristocrats into the state and reorganized society on the basis of wealth, determined at the census.Citizens were graded into six classes by property assessment. From them were recruited milites according to the equipment they could afford and the needs of the state.

From the wealthiest classes were recruited the heavy-armed infantry, equipped like the Greek hoplite warrior with helmet, round shield (clipeus), greaves and breastplate, all of bronze, and carrying a spear (hasta) and sword (not the gladius). In battle they followed the principle of "two forward, one back." The first and second acies, or lines of battle (principes, hastati), were forward; the triarii, or "third rank" (containing the veterani. or "old ones") was held in reserve. From the name, hastati, we can deduce that the hasta, a thrusting spear, was the weapon of choice. Triariis were equipped with a long spear, or pike, a shield and heavy armor.

The remaining class or classes (rorarii) were light-armed with the javelin (verutum). They were no doubt used for skirmishing, which provided some disruption of enemy ranks before the main event. The officers as well as the cavalry were either not in the six classes but were drawn from citizens who were enrolled as patricians of senatorial rank or equestrians (equites),also known as knights,they were of the first class. These were the aristocrats. Cavalry remained an aristocratic arm up to the introduction of motorized warfare.

All in all the Roman army consisted of 18 centuries of equites, 82 centuries of the first class (of which 2 centuries were engineers), 20 centuries each of the second, third and fourth classes and 32 centuries of the fifth class (of which 2 centuries were trumpeters).

Even these measures were inadequate to the challenges Rome was to face. They went to war with the Hernici, Volsci and Latini (Italics) undertook the reduction of Etruria and endured an invasion of Gauls under Brennus. Into the gap stepped one of the great generals Rome seemed able to produce at critical moments: Lucius Furius Camillus. He held various offices, such as interrex and dictator, but was never king himself.In the early fourth century BC Rome received its greatest humiliation, as the Gauls under Brennus sacked Rome itself.

The Romans wanted to abandon the city and resettle at Veii (an Etruscan city), but Camillus prevented it. If Rome was to re-establish her authority over central Italy, and be prepared to meet any similar disasters in future, some reorganization was needed. These changes were traditionally believed to have been the work of Camillus, but in another theory they were introduced gradually during the second half of the fourth century BC.Italy was not governed by city states like Greece, where armies met on large plains, deemed suitable by both sides, to reach a decision. Far more it was a collection of hill tribes using the difficult terrain to their advantage. Something altogether more flexible was needed to combat such foes than the unwieldy, slow-moving phalanx.

Undoubtedly the most important change was the abandonment of the use of the Greek phalanx. The legio, or "levy", was introduced at this time, with a structure of manipuli ("handsful"). A heavier shield, the scutum, took the place of the clipeus, and a heavier throwing spear, the pilum, was introduced. The line of battle was more open so that a rank could hurl a volley, preferably downhill, breaking the ranks of the enemy.

The first two lines carried pila. The rear rank, remaining in close order, and armed with hastae, were the pilani (not from pilum but from pilus, "closed rank"), in front of which were the antepilani carrying pila. In addition to these changes, the men began to receive pay, making a professional army possible.

The historian, Polybius, gives us a clear picture of the republican army at what is arguably its height in 160 BC. Serving in the army was part of civic duty in Rome. To serve in the infantry, one had to meet a property requirement.

The highest officers of the military were the two consuls, who were also the leading members of the executive branch of the government. Each of them ordinarily commanded an army group of two legions, which they also had the responsibility of raising. In the war-like state Rome was, the highest civilian officers were also the military chiefs of staff and the commanding generals in battle. They answered only to the senate.

Raising the legions was an annual affair. The term of service was one year, although many no doubt were picked year after year. The magistrates decided who in the tribes were to be presented for selection.The word we translate as "magistrate" was a tribal official, named, of course, a tribunus ("of the tribus"). Here a basic division of the military and civilian branches applied, as well as the subjection of the military to the civilian. The working organizations of the tribe were called comitia (the committee). They elected tribuni plebis, "tribunes of the people" as well as 24 tribuni militares, 6 per legion, who were careerists of at least 5 or 6 years service. A career would include both military and civilian offices. The 6 military tribunes were to be the senior staff of the legion.

On selection day, the presiding tribune sent the men of the tribe before the military tribunes in groups of four. The four senior staffs of the future legions oberved a priority of selection, which rotated. Each staff would take its pick, man by man, until 4200 men each had been selected, the complements of four legions. The selection of 16400 men must have taken several days, unless you imagine a very fast walk-through. Such a method begs us to suppose that arrangements had been negotiated in advance.If the circumstances of the state required it, the complement could be expanded to more men, or the consuls could draft as many as 4 legions each.

Additional forces could be drafted under ad hoc commanders termed proconsules, who served "in place of consuls." In the later republic, the relatively small number of legions commanded by the consuls (2-4) resulted in their power being overshadowed by the proconsuls, the provincial governors. They would often have more loyalty (see Marian Reforms) from their troops than their consular counterparts, and the same time have the ability to raise vast numbers of troops.

While the provincial armies were technically supposed to stay within the province their governor controlled, this was ignored by the middle of the 1st Century BC. By the end of the Republic, the various men involved in the civil wars had raised the number of legions throughout the Republic's provinces to more than fifty, many at the command of a single man.

The necessity to raise legions in a hurry, to offset battle losses, caused an abbreviation of the recruitment process. The government appointed two boards of three military tribunes each, who were empowered to enter any region in Roman jurisdiction for the purpose of enlisting men. These tribunes were not elected. The experience requirement was dropped in the case of aristocratic appointees. Some were as young as 18, but this age was considered acceptable for a young aristocrat on his way up the cursus honorum, or ladder of offices.

The appointed tribunes conducted an ad hoc draft, or dilectus, to raise men. They tended to select the youngest and most capable-looking. One is almost reminded of the British press gangs, except that Roman citizens were entitled to some process, no matter how abbreviated, but the press gangs took any male off the street. If they had to, the appointed tribunes took slaves, as after the Battle of Cannae.

Soldiers who had served out their time and obtained their discharge (missio), but had voluntarily enlisted again at the invitation of the consul or other commander were called evocati.

A standard Republican legion before the reforms of Marius (the early Republic) contained about 5000 men divided into the velites, the principes, and the hastati, of 1200 men each, the triarii, of 600 men, and the equites, of 800 men. The first three types stood forward in battle; the triarii, back. The velites and the equites were used mainly for various kinds of support.

The class system of Servius Tullius had already organized society in the best way to support the military. He had, so to speak, created a store in which the officers could shop for the resources they needed. The officers themselves were elected by the civilian centuries, usually from the classici or the patricii if the latter were not included in the classici (there is some question).

Available were 80 centuries of wealthy classici, 40 of young men, ages 17 to 45, and 40 of men 45 and older. These citizens could afford whatever arms and armor the officers thought they needed. The classici could go into any branch of the legion, but generally veterans were preferred for the triarii, young men for the velites. The rest were filled out from the young 40 centuries. The older 40 were kept for emergencies, which occurred frequently. These older men were roughly equivalent to the Army Reserve in the United States.If the arms requirement was less severe, or the expensive troops were in short supply, the recruiters selected from Classes 2 through 4, which again offered either older or younger men. Class 5 were centuries of specialists: carpenters, and so on. The Romans preferred not to use Class 6 but if the need was very great they were known to recruit from slaves and the poor, who would have to be equipped by the state.

The full equipage of arms and armor were the helmet with colored crest and face protectors, breastplates or chain mail (if you could afford it), greaves, the parma (a round shield), the scutum, an oblong wrap-around of hide on a wood frame, edged with metal, with the insignia of the legion painted on, the pilum, the hasta velitaris, a light javelin of about 3 feet with a 9-inch metal head, and a short sword they borrowed from Spanish tribes, the gladius. It was both pointed for thrusting and edged for slashing.

These arms could be combined in various ways, except that one line of battle had to be armed the same way. Most typical was a line of principes armed with pila, gladii, and defended by the scuta. The hastati could be armed that way or with the hasta and parma. The velites bore the hasta velitaris and depended on running to get them away after a throw, which is why only the young were chosen for that job.

The basic unit of the army was the company-sized centuria of 60 men commanded by a centurio. He had under him two junior officers, the optiones, who each had a standard-bearer, or vexillarius. Presumably he used them at will to form two squads. In addition was a squad of 20 velites attached to the century, probably instructed ad hoc by the centurion.

Two centuries made up a manipulum of 120 men. Each line of battle contained 10 maniples, 1200 men, exept that the triarii were only 600. The legion of 4200 infantry created in this way was supported by 800 equites, or cavalry, organized in 10 turmae (squadrons) of 80 horse each, under a master of horse (magister equitatum), who took orders from the legion commander. Cavalry was used for scouting, skirmishing and various sorts of clean-up, as well as being another reserve that could be thrown into the battle. The Republic was ignorant of armies on horseback, which, coming off the steppes of Central Asia in blitzkrieg operations, were to trouble the later empire.

Servius Tullius, most likely originally an Etruscan soldier of fortune (to whom he built temples), saw the ineptitude of the Roman army of the times and determined to remedy the situation. He was man deeply sympathetic to the ordinary Roman, for which value he paid with his life. Before that time he established the social foundations of a superior army. The army was not at first very successful, partly because it faced superior generals and partly through inexperience. Roman generals gave up trying to defeat Hannibal the Carthaginian as he ravaged Italy, and under Fabius Cunctator (the delayer) camped at a distance and watched the doings of the Carthaginians, never getting close enough to fight.

Perhaps much can be said for watching. At any rate, the army came into the hands of a family of careerists and professional soldiers, the Cornelii, a gens of the most ancient stock, patrician through and through in the best sense of the word, the first real successors to Servius. After much trial and error, suffering personal losses, they produced one of the best and most influential generals Rome ever had, Publius Cornelius Scipio. He built the Servian army into a victorious fighting machine.

Let the Carthaginians ravage Italy. Scipio took the war to Carthage, landing in North Africa with a republican army. The strategy succeeded; Hannibal was recalled at once, he came home immediately with a disrupted army and was beaten by Scipio at the Battle of Zama, 202 BC. With the tactics developed by Scipio, now entitled Africanus, and good generalship, the army at last lived up to the potential imparted to it by King Servius. Here is how the tactics worked.First the general picked his ground. The Romans now understood fairly well the importance of taking the initiative and picking your ground, with some infamous exceptions. If the terrain was not right, the army remained within its fortified camp (which was virtually unassailable) until the enemy moved on, and then followed him, waiting for an opportunity to engage.

The ideal terrain was a gently sloping hill with a stream at the bottom. The enemy would have to ford the stream and move up the slope. The film, Spartacus, recreates the ideal scene. The legion was drawn up in three lines of battle, with the turmae and the velites placed opportunistically. The hastati in front and the principes behind were stationed in a line of maniples like chess pieces, 10 per line, separated from each other. The two centuries of a maniple fought side by side. The line of principes was offset so as to cover the gaps in the hastati, and the Triarii, somewhat more thinly spread, covered the principes.

Roman formations were open. The last thing they wanted was to be crushed together and cut down without being able to use their weapons, as they had been so many times before, and as so many armies who never studied Roman warfare were to be later. Every man must by regulation be allowed one square yard in which to fight, and square yards were to be separated by gaps of three feet.Now came the moment of battle. The turmae and the bands of velites (skirmishers) made forays opportunistically, trying to disrupt the ranks of the enemy or prevent them from crossing the stream (if there was one). While they were doing this the rest of the legion advanced. At a signal, the skirmishers retired through or around Roman ranks (there probably were trumpet calls, but we know little of them).

Picking up speed, the hastati launched pila. These heavy missiles had a range of about 100 yards. On impact they drove through shields and armor both, pinning men together and disrupting the line. Just before the hastati were to close, the principes launched a second volley over their heads. The hastati now drew gladii and closed. So great was the impact, we hear from Caesar, that sometimes the men would jump up on the enemy shields to cut downward.

What happened next depended on the success of the hastati. If they were victorious, they were joined by the principes, who merged into their line to fill the gaps and make up losses. The triarii moved to the flanks to envelop the enemy. If the hastati were not victorious, they merged backward into the principes. The third line remained in reserve unless the other two failed, in which case the front two merged into the third.

Such was the attack of a Roman legion, which was nearly always successful, if it was done correctly. Later the Romans learned how to secure their flanks with ballistae and other “cannon-like” throwing or shooting machines. The attack depended in effect on a schwerpunkt, a massing of firepower on the enemy’s front line. Whenever the legions could not set it up, they were generally massacred.

By the end of the 2nd century BC the Republican army was experiencing a severe manpower shortage. In addition to this shortage, Roman armies were now having to serve for longer periods to fight wars further away from their home. The Gracchi had attempted to resolve the former problem by redistributing public land to the lower classes, and thereby increase the number of men eligible for military service, but were killed before they could achieve this. Thus, the extremely popular Gaius Marius at the end of the 2nd century used his power to reorganize the Republican army. Firstly, while still technically illegal, he recruited men from the lower classes who did not meet the official property requirement. He also reorganized the legions into the cohort system, doing away with the manipular system. The new legions were made up of 10 cohorts, each with 6 centuries of 80 men.

The first cohort carried the new legionary standard, a silver or gold eagle called the aquila. This cohort had only 5 centuries, but each century had double the men of normal centuries. All together, each legion had approximately 4,800 men. The Marian reforms had great political fallout as well. Although the officer corps was still largely composed of Roman aristocrats, the rank-and-file troops were all lower-class men - serving in the legions became less and less of every citizen's traditional civic duty to Rome and more exclusively a means to win glory for your family as an officer. It also meant that legions were now (more or less) permanent formations, not just temporary armies deployed according to need (the Latin word 'legio' is actually their word for 'levy'). As enduring units, they were able to become more effective fighting forces; more importantly, they could now form lasting loyalties to their commanders, as the typical 1-year consul system began to break down and generals served for greater durations. This is what made the civil wars possible, and it is why scholars often cite the Marian Reforms as the beginning of the end for the Roman Republic.

During the reign of Augustus and Trajan the army became a professional one. Its core of legionaries was composed of Roman citizens who served for a minimum of twenty five years. Augustus in his reign tried to eliminate the loyalty of the legions to the generals who commanded them, forcing them to take an oath of allegiance directly to him. While the legions remained relatively loyal to Augustus during his reign, under others, especially the more corrupt emperors or those who unwisely treated the military poorly, the legions often took power into their own hands. Legions continued to move farther and farther to the outskirts of society, especially in the later periods of the empire as the majority of legionaries no longer came from Italy, and were instead born in the provinces. The loyalty the legions felt to their emperor only degraded more with time, and lead in the 2nd Century and 3rd Century to a large number of military usurpers and civil wars.

By the time of the military officer emperors that characterized the period following the Crisis of the Third Century the Roman army was just as likely to be attacking itself as an outside invader.Both the pre- and post-Marian armies were greatly assisted by auxiliary troops. A typical Roman legion was accompanied by a matching auxiliary legion. In the pre-Marian army these auxiliary troops were Italians, and often Latins, from cities near Rome.

The post-Marian army incorporated these Italian soldiers into its standard legions (as all Italians were Roman citizens after the Social War). Its auxiliary troops were made up of foreigners from provinces distant to Rome, who gained Roman citizenship after completing their twenty five years of service. This system of foreign auxiliaries allowed the post-Marian army to strengthen traditional weak points of the Roman system, such as light missile troops and cavalry, with foreign specialists, especially as the richer classes took less and less part of military affairs and the Roman army lost much of its domestic cavalry.

At the beginning of the Imperial period the number of legions was 60, which Augustus more than halved to 28, numbering at approximately 160,000 men. As more territory was conquered throughout the Imperial period, this fluctuated into the mid-thirties. At the same time, at the beginning of the Imperial period the foreign auxiliaries made up a rather small portion of the military, but continued to rise, so that by the end of the period of the Five Good Emperors they probably equalled the legionnaires in number, giving a combined total of between 300,000 and 400,000 men in the Army.

Under Augustus and Trajan, the army had become a highly efficient and thoroughly professional body, brilliantly led and staffed. To Augustus fell the difficult task of retaining much that Caesar had created, but on a permanent peace-time footing. He did so by creating a standing army, made up of 28 legions, each one consisting of roughly 6000 men. Additional to these forces there was a similar number of auxiliary troops. Augustus also reformed the length of time a soldier served, increasing it from six to twenty years (16 years full service, 4 years on lighter duties).

The standard of a legion, the so-called aquila (eagle) was the very symbol of the unit's honor. The aquilifer was the man who carried the standard, he was almost as high in rank as a centurion. It was this elevated and honorable position which also made him the soldiers' treasurer in charge of the pay chest.

A legion on the march relied completely on its own resources for weeks. In addition to his weapons and armour, each man carried a marching pack that included a cooking pot, some rations, clothes and any personal possessions. Furthermore, to make camp each night every man carried tools for digging as well as two stakes for a palisade. Weighed down by such burdens it is little wonder that the soldiers were nicknamed 'Marius' Mules'.

There has over time been much debate regarding how much weight a legionary actually had to carry. Now, 30 kg (ca. 66 lbs) is generally considered the upper limit for an infantryman in modern day armies. Calculations have been made which, including the entire equipment and the 16 day's worth of rations, brings the weight to over 41 kg (ca. 93 lbs). And this estimate is made using the lightest possible weights for each item, it suggest the actual weight would have been even higher. This suggests that the sixteen days rations were not carried by the legionaries. the rations referred to in the old records might well have been a sixteen days ration of hard tack (buccellatum), usually used to supplement the daily corn ration (frumentum).

By using it as an iron ration, it might have sustained a soldier for about three days. The weight of the buccellatum is estimated to have been about 3 kg, which, given that the corn rations would add more than 11 kg, means that without the corn, the soldier would have carried around 30 kg (66 lbs), pretty much the same weight as today's soldiers.

The necessity for a legion to undertake quite specialised tasks such as bridge building or engineering siege machines, required there to be specialists among their numbers. These men were known as the immunes, 'excused from regular duties'. Among them would be medical staff, surveyors, carpenters, veterinaries, hunters, armourers - even soothsayers and priests. When the legion was on the march, the chief duty of the surveyors would be to go ahead of the army, perhaps with a cavalry detachment, and to seek out the best place for the night's camp. In the forts along the empire's frontiers other non-combatant men could be found.

For an entire bureaucracy was necessary to keep the army running. So scribes and supervisors, in charge of army pay, supplies and customs. Also there would be military police present.As a unit, a legion was made up of ten cohorts, each of which was further divided into six centuries of eighty men, commanded by a centurion. The commander of the legion, the legatus, usually held his command for three or four years, usually as a preparation for a later term as provincial governor.

The legatus, also referred to as general in much of modern literature, was surrounded by a staff of six officers. These were the military tribunes, who - if deemed capable by the legatus - might indeed command an entire section of a legion in battle. The tribunes, too, were political positions rather than purely military, the tribunus laticlavius being destined for the senate.

Another man, who could be deemed part of the general's staff, was the centurio primus pilus. This was the most senior of all the centurions, commanding the first century of the first cohort, and therefore the man of the legion, when it was in the field, with the greatest experience (in Latin, "primus pilus" means "first javelin", as the primus pilus was allowed to hurl the first javelin in battle). The primus pilus also oversaw the everyday running of the forces.

Together with non-combatants attached to the army, a legion would count around 6000 men. The 120 horsemen attached to each legion were used as scouts and dispatch riders. They were ranked with staff and other non-combatants and allocated to specific centuries, rather than belonging to a squadron of their own.

The senior professional soldiers in the legion was likely to be the camp prefect, praefectus castrorum. He was usually a man of some thirty years service, and was responsible for organization, training, and equipment.Centurions, when it came to marching, had one considerable privilege over their men. Whereas the soldiers moved on foot, they rode on horseback.

Another significant power they possessed was that of beating their soldiers. For this they would carry a staff, perhaps two or three foot long. Apart from his distinctive armour, this staff was one of the means by which one could recognise a centurion. One of the remarkable features of centurions is the way in which they were posted from legion to legion and province to province. It appears they were not only highly sought after men, but the army was willing to transport them over considerable distances to reach a new assignment.

The most remarkable aspect of the centurionate though must be that they were not normally discharged but died in service. Thus, to a centurion the army was truly his life. Each centurion had an optio, so called because originally he was nominated by the centurion. The optiones ranked with the standard bearers as principales receiving double the pay of an ordinary soldier.

The title optio ad spem ordinis was given to an optio who had been accepted for promotion to the centurionate, but who was waiting for a vacancy. Another officer in the century was the tesserarius, who was mainly responsible for small sentry pickets and fatigue parties, and so had to receive and pass on the watchword of the day. Finally there was the custos armorum who was in charge of the weapons and equipment.

Front Line 5th Cohort 4th Cohort 3rd Cohort 2nd Cohort 1st Cohort

Second Line 10th Cohort 9th Cohort 8th Cohort 7th Cohort 6th Cohort

The first cohort of any legion were its elite troops. So too the sixth cohort consisted of "the finest of the young men", the eighth contained "selected troops", the tenth cohort "good troops". The weakest cohorts were the 2nd, 4th, 7th and the 9th cohorts. It was in the 7th and 9th cohorts one would expect to find recruits in training.

The last major reform of the Imperial Army came under the reign of Diocletian in the late 3rd Century. During the instability that had marked most of that century, the army had fallen in number and lost much of its ability to effectively police and defend the empire. He quickly recruited a large number of men, increasing the number of legionnaires from between 150,000-200,000 to 350,000-400,000, effectively doubling the number in a case of quantity over quality.

The first Roman wars were wars of expansion and defence, aimed at protecting Rome itself from neighboring cities and nations by defeating them in battle. This sort of warfare characterized the early Republican Period when Rome was focused on consolidating its position in Italy, and eventually conquering the peninsula. Rome first began to make war outside the Italian peninsula in the Punic wars against Carthage. These wars, starting in 264 BC saw Rome become a Mediterranean power, with territory in Sicily, North Africa, Spain, and, after the Macedonian wars, Greece.

One important point that must be understood is that the Rome did not conquer most nations outright, at least at first, but instead forced them into a submissive position as allies and client states. These allies supplied men, money, and supplies to Rome against other opponents.

It wasn't until the late Republic that the expansion of the Republic started meaning actual annexation of large amounts of territory, however in this period, civil war became an increasingly common feature. In the last century before the common era at least 12 civil wars and rebellions occurred. These were generally started by one charismatic general who refused to surrender power to the Roman Senate, which appointed generals, and so had to be opposed by an army loyal to the Senate. This pattern did not break until Octavian (later Caesar Augustus) ended it by becoming a successful challenger to the Senate's authority, and was crowned emperor.

As the emperor was a centralized authority with power focused in Rome, this gave both a benefit and weakness to expansion under the Roman Empire. Under powerful and secure emperors such as Augustus and Trajan, great territorial gains were possible, but under weaker rulers such as Nero and Domitian, weakness resulted in nothing more than usurpation. One thing that all successful emperors had to accomplish was the loyalty of the legions throughout the empire. Weak emperors such as those relied upon generals to carry out their direct actions along the border, especially considering their requirement to stay in Rome to maintain power. This meant that often expansion in the empire came in leaps and bounds rather than a slow march.

Another important point to remember is that many of the territories conquered in the imperial period were former client states of Rome whose regimes had degraded into instability, requiring armed intervention, often leading to outright annexation.

Unfortunately, the weakness of some emperors meant that these generals could wrest control of those legions away. The third century saw a crisis and a high number of civil wars similar to those that characterized the end of the Republic. Much like then, generals were wrestling control of power based upon the strength of the local legions under their command. Ironically, while it was these usurpations that lead to the break up of the Empire during that crisis, it was the strength of several frontier generals that helped reunify the empire through force of arms.

Eventually, the dynastic structure of the imperial office returned due to the centralization of loyalty and control of the military once more, and then collapsed once again for the same reasons as before, leading to the destruction of the Western Half of the Empire. At this point, Roman military history becomes Byzantine military history.

Roman Navy