Ruins of Deir el-Medina is a UNESCO World Heritage site

Ruins of Deir el-Medina is a UNESCO World Heritage site

Deir el-Medinas an ancient Egyptian village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt (ca. 1550-1080 BCE) The settlement's ancient name was Set maat "The Place of Truth", and the workmen who lived there were called "Servants in the Place of Truth".

During the Christian era, the temple of Hathor was converted into a church from which the Egyptian Arabic name Deir el-Medina ("the monastery of the town") is derived.

At the time when the world's press was concentrating on Howard Carter's discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, a team led by Bernard Bruyre began to excavate the site. This work has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world that spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organisation, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community can be studied in such detail.

The site is located on the west bank of the Nile, across the river from modern-day Luxor. The village is laid out in a small natural amphitheatre, within easy walking distance of the Valley of the Kings to the north, funerary temples to the east and south-east, with the Valley of the Queens to the west. The village may have been built apart from the wider population in order to preserve secrecy in view of sensitive nature of the work carried out in the tombs.

A significant find of papyri was made in the 1840s in the vicinity of the village and many objects were also found during the course of the 19th century. The archaeological site was first seriously excavated by Ernesto Schiaparelli between 1905-1909 which uncovered large amounts of ostraca. A French team directed by Bernard Bruyre excavated the entire site, including village, dump and cemetery, between 1922-1951. Unfortunately through lack of control it is now thought that about half of the papyri recovered were removed without the knowledge or authorization of the team director. Around five thousand ostraca of assorted works of commerce and literature were found in a well close to the village.

The first datable remains of the village belong to the reign of Thutmose I (c. 1506-1493 BCE) with its final shape being formed during the Ramesside Period At its peak, the community contained around sixty-eight houses spread over a total area of 5,600 metres sq. with a narrow road running the length of the village. The main road through the village may have been covered to shelter the villagers from the intense glare and heat of the sun.

The size of the habitations varied, with an average floor space of 70 metres sq. but the same construction methods were used throughout the village. Walls were made of mudbrick, built on top of stone foundations. Mud was applied to the walls, which were then painted white on the external surfaces, while some of the inner surfaces were whitewashed up to a height of around one metre. A wooden front door might have carried the occupants' name.

Houses consisted of four to five rooms, comprising an entrance, main room, two smaller rooms, kitchen with cellar and staircase leading to the roof. The full glare of the sun was avoided by situating the windows high up on the walls. The main room contained a mudbrick platform with steps which may have been used as a shrine or a birthing bed. Nearly all houses contained niches for statues and small altars. The tombs built by the community for their own use include small rock-cut chapels and substructures adorned with small pyramids.

Due to its location, the village is not thought to have provided a pleasant environment. The walled village reflects the shape of the narrow valley in which it's situated, with the barren surrounding hillsides reflecting the desert sun and the hill of Gurnet Murai cutting off the north breeze, as well as any view of the verdant river valley. The village was abandoned c. 1110-1080 BCE during the reign of Ramesses XI (whose tomb was the last of the royal tombs built in the Valley of the Kings) due to increasing threats from tomb robbery, Libyan raids and the instability of civil war. The Ptolemids later built a temple to Hathor on the site of an ancient shrine dedicated to her.

The surviving texts record the events of daily life rather than major historical incidents. Personal letters reveal much about the social relations and family life of the villagers. The ancient economy is documented by records of sales transactions that yield information on prices and exchange. Records of prayers and charms illustrate ordinary popular conceptions of the divine, whilst researchers into ancient law and practice find a rich source of information recorded in the texts from the village. Many examples of the most famous works of ancient Egyptian literature have also been found. Thousands of papyri and ostraca still await publication.

The settlement was home to a mixed population of Egyptians, Nubians and Asiatics who were employed as labourers, (stone-cutters, plasterers, water-carriers), as well as those involved in the administration and decoration of the royal tombs and temples. The artisans and the village were organized into two groups, left and right gangs who worked on opposite sides of the tomb walls similar to a ship's crew, with a foreman for each who supervised the village and its work.

As the main well was thirty minutes walk from the village, carriers worked to keep the village regularly supplied with water. When working on the tombs, the artisans stayed overnight in a camp overlooking the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut (c. 1479-1458 BCE) that is still visible today. Surviving records indicate that the workers had cooked meals delivered to them from the village.

Based on analysis of income and prices, the workmen of the village would, in modern terms, be considered middle class. As salaried state employees they were paid in rations at up to three times the rate of a field hand, but unofficial second jobs were also widely practiced. At great festivals such as the heb sed the workmen were issued with extra supplies of food and drink to allow a stylish celebration.

The working week was eight days followed by two days holiday, though the six days off a month could be supplemented frequently due to illness, family reasons and, as recorded by the scribe of the tomb, arguing with wife or having a hangover. Including the days given over to festivals, over one-third of the year was time-off for the villagers during the reign of Merneptah (c. 1213-1203 BCE).

During their days off the workmen could work on their own tombs, and since they were amongst the best craftsmen in Ancient Egypt who excavated and decorated royal tombs, their own tombs are considered to be some of the most beautiful on the west bank.

A large proportion of the community, including women, could at least read and possibly write.

The jobs of the workers would have been considered desirable and prized positions, with the posts being inheritable.

The examples of love songs recovered show how friendship between the sexes was practised, as was social drinking by both men and women. Egyptian marriages amongst commoners were monogamous but little is known about the marriage or wedding arrangements from surviving records. It was not unusual for couples to have six or seven children, with some recorded as having ten.

Separation, divorce and remarriage occurred. Merymaat is recorded as wanting a divorce on account of his mother in-law's behavior. Female slaves could become surrogate mothers in cases where the wife was infertile and in doing so raise their status and procure their freedom.

The community could move freely in and out of the walled village but for security reasons the only outsiders allowed to enter the site were those with good work-related reasons.

In Arabic Deir El Medina means "the monastery of the city" most probably referring to the fact that this ancient historical site was transformed into a Christian worship center during the Coptic period in Egypt, just like the Temple of Hatshepsut (which was called El Deir El Bahry, or "the Monastery of the North.") The ancient Egyptian name of Deir El Medina was "ta set Maat" which means "the place of reality." This town was constructed to host the workers and the artists who built the royal and private tombs on the Western Bank of Luxor.

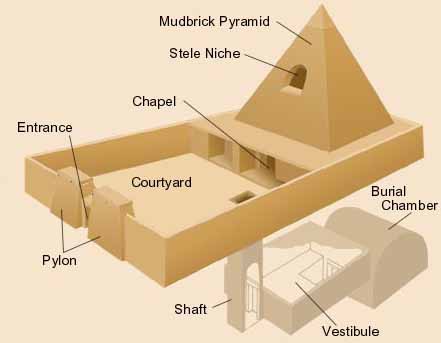

Behind the town of Deir El Medina, situated on the slopes of the mountains, the workers and artists who once lived in the town constructed their own tombs where they were buried near their greatest achievements. These tombs, much smaller than those of the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, were nevertheless quite elegant. They consisted of a cult chapel with the entrance ornamented with a mud-brick pyramid and a burial chamber which was decorated with charming paintings.

Situated in a valley at the foot of the Theban Mountain, Deir El Medina was the home of the artists, craftsmen, and workers who created, built, and ornamented the royal and private tombs of the Kings and Queens of Egypt which dazzled the whole world when they were discovered. The workers and artists who lived in Deir El Medina were divided into two squads and each team used to work for eight hours a day and had the right to take two days off every eight days of working. Supervised by a headman, each squad used to consist of 15 to 30 individuals who worked at the same time on both sides of the tomb digging with hammers and bronze grave digging implements. As the builders start working their way into the mountain, the other workers would trim and smooth out the walls. They would add a layer of a mixture of calcareous sand, clay, and straw and then another layer of plaster mixed with water.

After the preparation of the walls was completed, the artists would begin their work drawing on the walls with red ocher and then afterward they would make the corrections needed using black chalk. After the drawing is done, it would be the time for the sculptures that would carve the mixture used in the first phase into bas-reliefs. Then it would be the turn of the decorators who would color the bas-reliefs with different paints.

Some of these paints and colors were natural, like the ones derived from ground rocks from the mountains, while others were artificially made like the popular ancient Egyptian blue color which was manufactured by heating copper with sand and alkali. This means that while the diggers were still working in the innermost part of the tomb, other sections of the tomb located close to the mountains were already completed and finished by other workers. Following this approach, the ancient Egyptian builders and workers succeeded in constructing tombs, rather small, but they were able to complete a tomb only in few months time, which is very impressive.

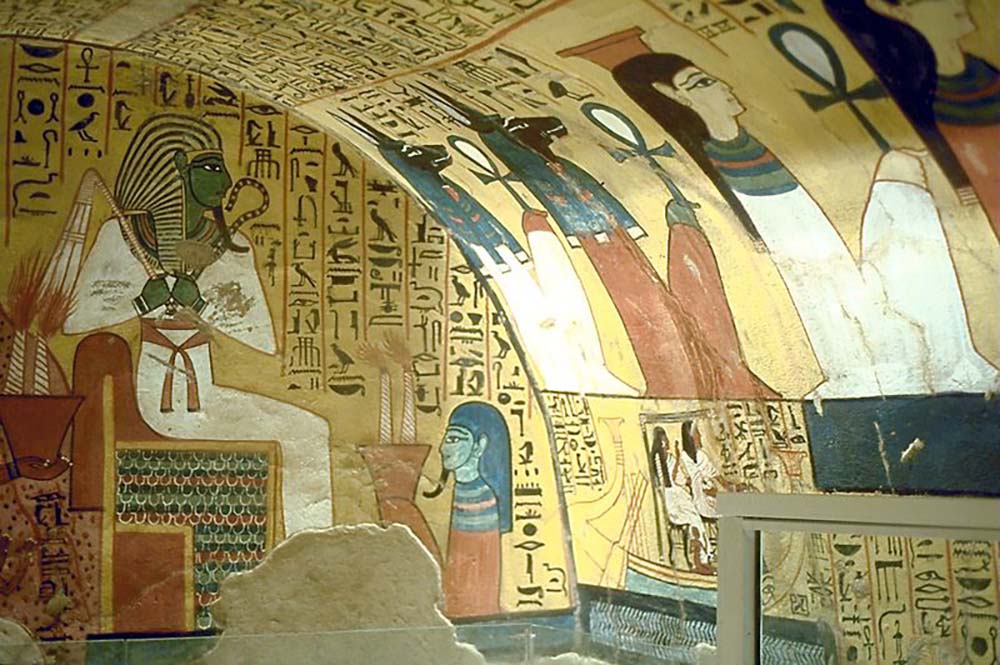

Inerkhau, the headman of the lord of the two lands in the place of the truth during the reign of Ramses III and Ramses VI had his tomb constructed in the tombs of Deir El Medina which are featured with paintings illustrating passages from the Book of the Dead.

The tomb of Inerkhau was unearthed in the middle of the 19th century by the famous German archeologist Richard Lepsuis. Lepsuis removed two paintings which were inside the tomb of Amenophis and his wife and they are now on display in the Museum of Berlin.

A vestibule which was originally rich with different paintings precedes the burial chamber. Most of the painting and the decoration works of the tomb are inspired by the Book of the Dead, the most important manuscript of the burial rituals and the underworld of ancient Egypt. However, there are also some scenes of the daily life of Inerkhau portrayed on the west wall of the burial chamber. This painting displays the owner of the tomb Inerkhau in some sort of a family portrait gathering with his wife and his four children.

On the west walls, there are also around 16 smaller scenes relate to the Book of the Dead. The scenes include the cat of Heliopolis killing the Apophis under the Ished tree, a musician playing on the harp for Inerkhau and his wife, and a scene of Inerkhau being taken to the god Osiris by the god Thoth.

On the back wall of the burial chamber, there is a scene of Inerkhau accompanied by his two daughters presenting offerings to Osiris and Ptah, the two most important gods of the reign of the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

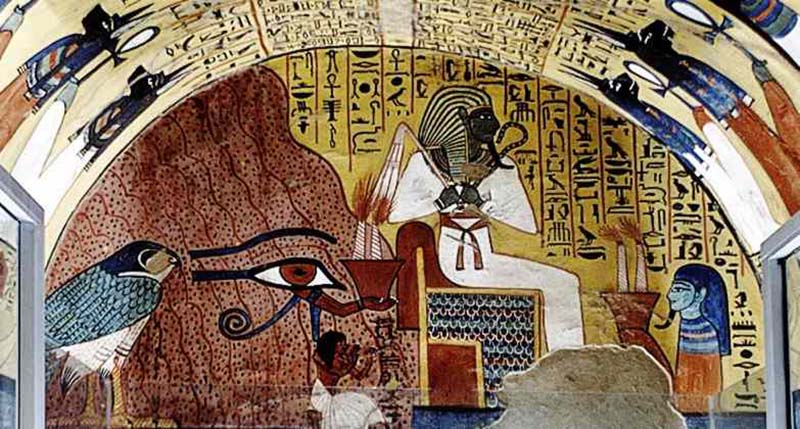

An artist who lived in the reign of Sethos I and Ramses II, the tomb of Sennedjem is among the most famous tombs in the Necropolis of Deir El Medina because the tomb was finely preserved when it was discovered to the extent that the paintings seem as if they were completed only a few years ago.

Sennedjem had the title of the servant of the place of the truth and his tomb was discovered in 1886 when the archeologists found an intact burial chamber and a large collection of funerary equipment that was transformed to be exhibited in the Egyptian Museum. The burial chamber is fully covered with paintings that date back to the style common during the reign of the dynasty Ramses which is based mainly on displaying the life of the deceased in the afterlife.

On the right hand of the entrance to the burial chamber, there is a painting that shows Sennedjem and his wife before entering into the kingdom of Osiris in the afterlife, which is a famous scene from the Book of the Dead. On the other hand, there is a scene of Sennedjem in his daily life and above this scene, the owner of the tomb is already mummified and protected by the god Isis in the form of a falcon.

Deir el-Medina lies in a small valley between the western slope of the Theban mountain and the small hill of Qurnet Murai. It was the workers village where craftsman and other lived who actually constructed and decorated the tombs on the West Bank at Luxor (ancient Thebes). The artisans who lived in this community built their tombs only a few dozen meters from their town on the heights that overlook the village. The excavated burials here include those of Sennedjem (TT1), a foreman named Inerkhau (TT 229 and TT 359), Pashedu (TT 3), Nakhtamen (TT 218), a sculptor named Ipuy (TT 217), Nebenmaat (TT 219) and Nakhtamen (TT 335). They were all artists during the Ramesside period and were well known for their work on the West Bank. Apparently they paid considerable attention to their own tombs and the arrangement of their necropolis.

In the beginning these were personal tombs, but over time their function was extended to also receive the remains of other family members. However, the structure of the tombs in the necropolis was fairly uniform. They built their tombs almost as if there was a building code requiring specific architectural elements. Customarily, these tombs had an entrance through a small pylon into one or two open courtyards. At the rear of the last courtyard was a small chapel with an entrance made of unburned mudbrick and toped by a small pyramid that occasionally had several rooms excavated in the rock.

In every instance we know of, on the back wall of this chapel was a niche where a statue of the deceased and a stele inscribed with the text of the hymn to the sun was housed. This chapel was intended for the worship of the deceased. Even those of not of royal blood attempted to keep their name known and therefore so too their soul.

The deceased was buried along with a rich set of funerary objects in a burial chamber excavated below ground level. The underground chambers were reached by way of a steep stair shaft that was either located in the courtyard or one of the interior rooms.

The burial chambers had vaulted ceilings and often beautiful decorations, usually of the deceased and his family engaged in their everyday activities.. Other scenes depicted ritualistic activities such as the embalming of the deceased or the Opening of the Mouth ritual. Inscriptions from the Book of the Dead also often adorned the walls.