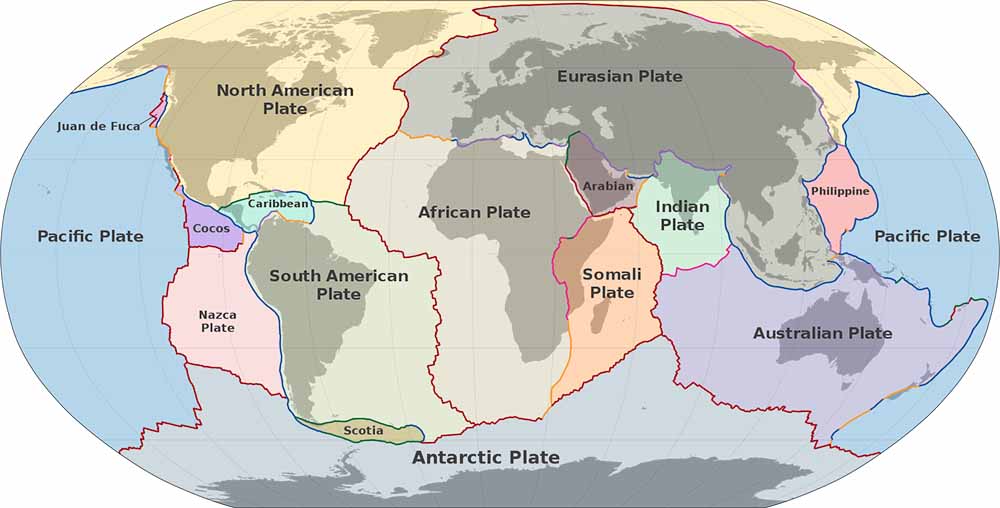

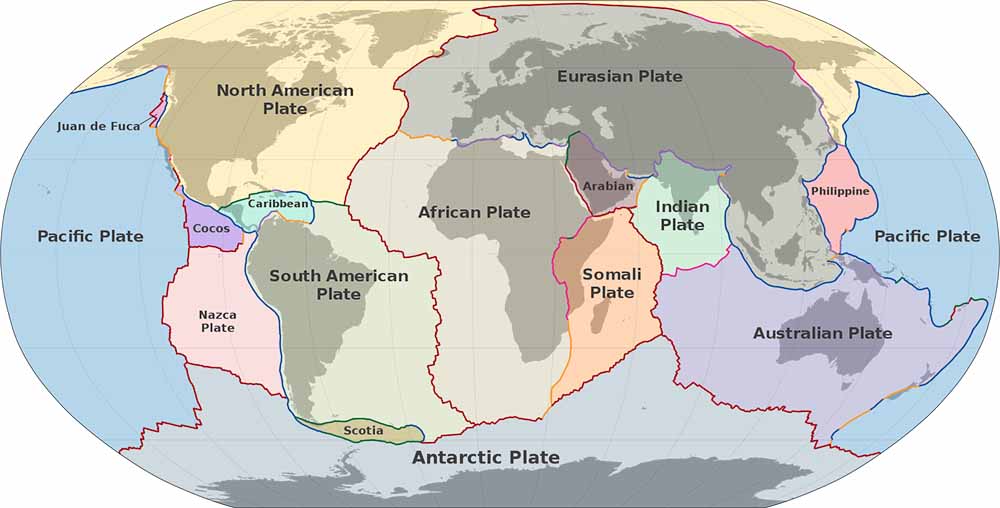

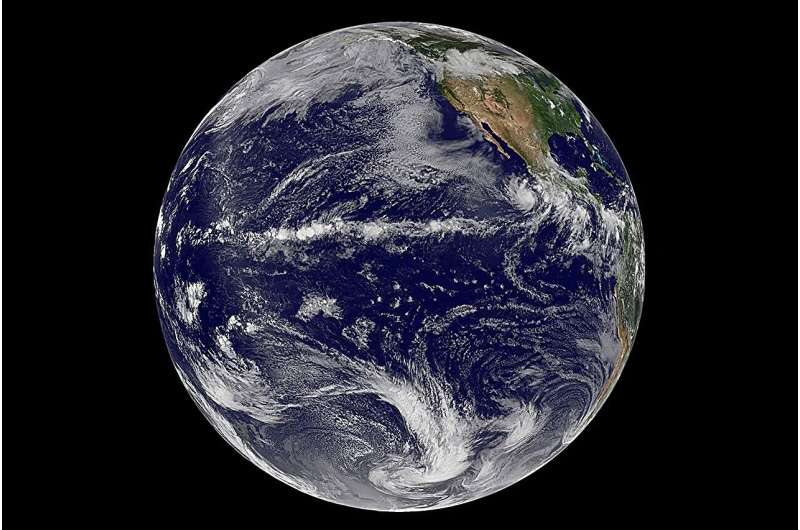

Tectonic plates comprise the bulk of the continents and the Pacific Ocean. A major plate is any plate with an area greater than 20 million km2. There are also minor pates with lesser areas.

Plate tectonics, from Greek "builder" or "mason", is a theory of geology that has been developed to explain the observed evidence for large scale motions of the Earth's lithosphere. The theory encompassed and superseded the older theory of continental drift from the first half of the 20th century and the concept of seafloor spreading developed during the 1960s.

Plate tectonics is a theory of geology that has been developed to explain the observed evidence for large scale motions of the Earth's lithosphere. The theory encompassed and superseded the older theory of continental drift from the first half of the 20th century and the concept of seafloor spreading developed during the 1960s.

The outermost part of the Earth's interior is made up of two layers: above is the lithosphere, comprising the crust and the rigid uppermost part of the mantle. Below the lithosphere lies the asthenosphere. Although solid, the asthenosphere has relatively low viscosity and shear strength and can flow like a liquid on geological time scales. The deeper mantle below the asthenosphere is more rigid again. This is, however, not due to cooler temperatures but due to high pressure.

The lithosphere is broken up into what are called tectonic plates, in the case of Earth, there are seven major and many minor plates (see list below). The lithospheric plates ride on the asthenosphere. These plates move in relation to one another at one of three types of plate boundaries: convergent or collision boundaries, divergent or spreading boundaries, and transform boundaries. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along plate boundaries. The lateral movement of the plates is typically at speeds of 0.66 to 8.50 centimeters per year.

The lithosphere essentially "floats" on the asthenosphere and is broken-up into ten major plates: African, Antarctic, Australian, Eurasian, North American, South American, Pacific, Cocos, Nazca, and the Indian plates. These plates (and the more numerous minor plates) move in relation to one another at one of three types of plate boundaries: convergent (two plates push against one another), divergent (two plates move away from each other), and transform (two plates slide past one another). Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along plate boundaries (most notably around the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire).

Plate tectonic theory arose out of two separate geological observations: continental drift, noticed in the early 20th century, and seafloor spreading, noticed in the 1960s. The theory itself was developed during the late 1960s and has since almost universally been accepted by scientists and has revolutionized the Earth sciences akin to the development of the periodic table for chemistry, the discovery of the genetic code for genetics, or evolution in biology. Read more

African Plate - Tectonic plate underlying Africa - 61,300,000 km2

Antarctic Plate - Major tectonic plate containing Antarctica and the surrounding ocean floor - 60,900,000 km2

Eurasian Plate - Tectonic plate which includes most of the continent of Eurasia - 67,800,000 km2

Indo-Australian Plate - A major tectonic plate formed by the fusion of the Indian and the Australian Plates (sometimes considered to be two separate tectonic plates) - 58,900,000 km2

Australian Plate - Major tectonic plate - 47,000,000 km2

Indian Plate - A minor tectonic plate that got separated from Gondwana - 11,900,000 km2

North American Plate - Large tectonic plate including most of North America, Greenland and part of Siberia - 75,900,000 km2

Pacific Plate - Oceanic tectonic plate under the Pacific Ocean - 103,300,000 km2

South American Plate - Major tectonic plate which includes most of South America and a large part of the south Atlantic - 43,600,000 km2

These smaller plates are often not shown on major plate maps, as the majority of them do not comprise significant land area. For purposes of this list, a minor plate is any plate with an area less than 20 million km2 but greater than 1 million km2.

Amurian Plate - A minor tectonic plate in eastern Asia

Arabian Plate - Minor tectonic plate - 5,000,000 km2

Burma Plate - Minor tectonic plate in Southeast Asia - 1,100,000 km2

Caribbean Plate - A mostly oceanic tectonic plate including part of Central America and the Caribbean Sea - 3,300,000 km2

Caroline Plate - Minor oceanic tectonic plate north of New Guinea - 1,700,000 km2

Cocos Plate - Young oceanic tectonic plate beneath the Pacific Ocean off the west coast of Central America - 2,900,000 km2

Nazca Plate - Oceanic tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin - 15,600,000 km2[note 1]

New Hebrides Plate - Minor tectonic plate in the Pacific Ocean near Vanuatu - 1,100,000 km2

Okhotsk Plate - Minor tectonic plate in Asia

Philippine Sea Plate - Oceanic tectonic plate to the east of the Philippines - 5,500,000 km2

Scotia Plate - Minor oceanic tectonic plate between the South American and Antarctic Plates - 1,600,000 km2

Somali Plate - Minor tectonic plate including the east coast of Africa and the adjoining seabed - 16,700,000 km2

Sunda Plate - Tectonic plate including Southeast Asia

Yangtze Plate - Small tectonic plate carrying the bulk of southern China

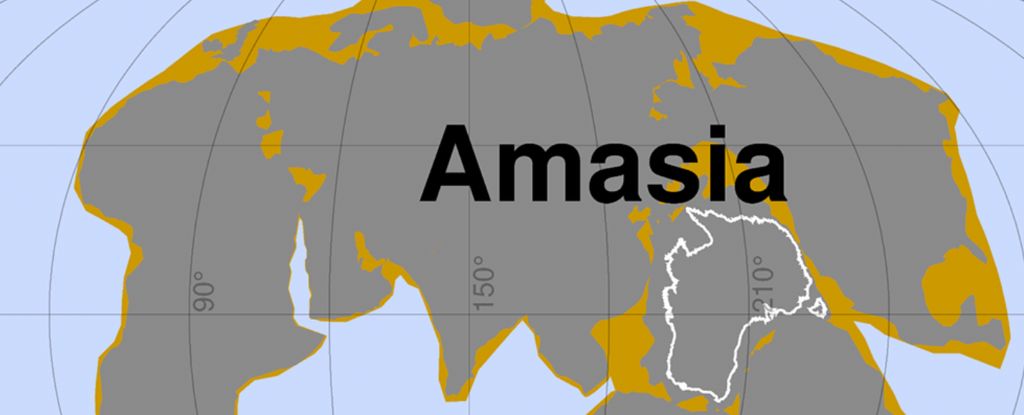

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leaves room for interpretation and is easier to apply to Precambrian times. To separate supercontinents from other groupings, a limit has been proposed in which a continent must include at least about 75% of the continental crust then in existence in order to qualify as a supercontinent.

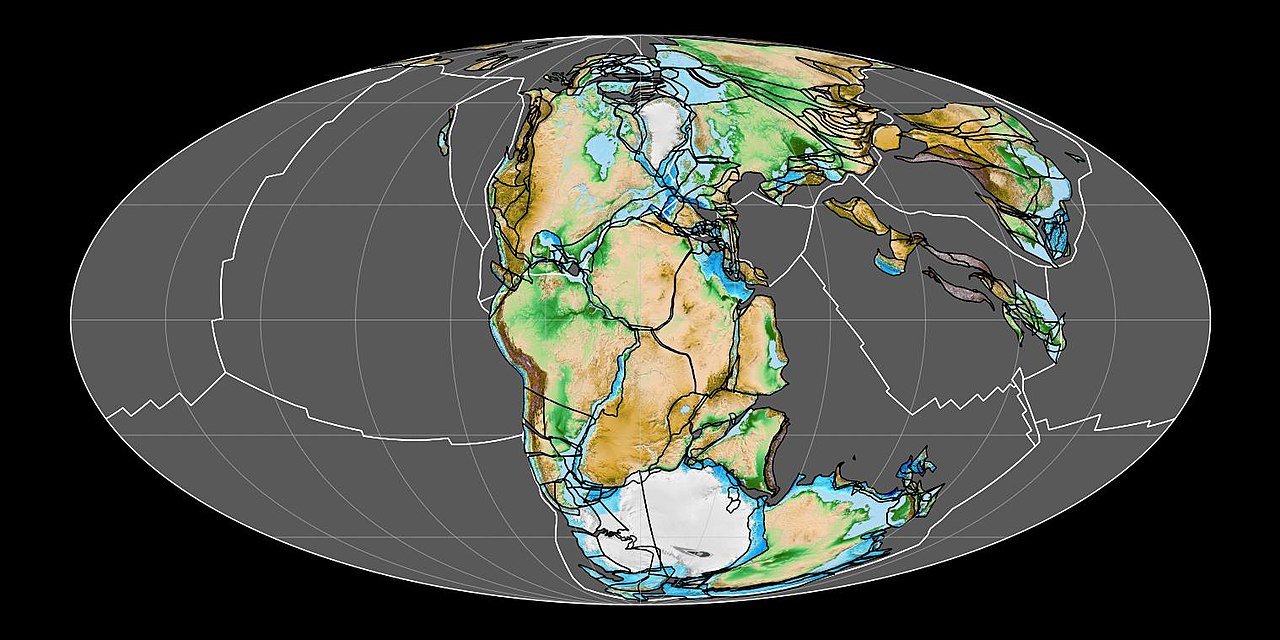

Moving under the forces of plate tectonics, supercontinents have assembled and dispersed multiple times in the geologic past. According to modern definitions, a supercontinent does not exist today; the closest is the current Afro-Eurasian landmass, which covers approximately 57% of Earth's total land area. The last period in which the continental landmasses were near to one another was 336 to 175 million years ago, forming the supercontinent Pangaea.

The positions of continents have been accurately determined back to the early Jurassic, shortly before the breakup of Pangaea. Pangaea's predecessor Gondwana is not considered a supercontinent under the first definition since the landmasses of Baltica, Laurentia and Siberia were separate at the time. A future supercontinent, termed Pangaea Proxima, is hypothesized to form within the next 250 million years. Read more ...

Fountains of diamonds that erupt from Earth's center are revealing the lost history of supercontinents Live Science - January 15, 2024

Diamonds seem to reach Earth's surface in massive volcanic eruptions when supercontinents break up, and they form when continents come together.

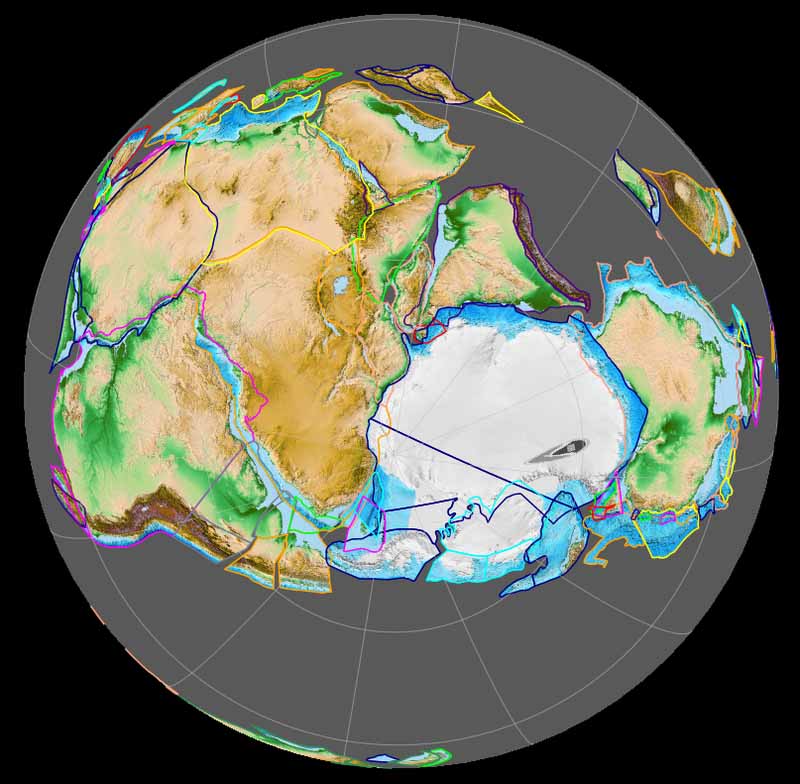

Gondwana was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. It was formed by the accretion of several cratons (a large stable block of the earth's crust), beginning c. 800 to 650 Ma with the East African Orogeny, the collision of India and Madagascar with East Africa, and was completed c. 600 to 530 Ma with the overlapping Brasiliano and Kuunga orogenies, the collision of South America with Africa, and the addition of Australia and Antarctica, respectively.

Eventually, Gondwana became the largest piece of continental crust of the Palaeozoic Era, covering an area of about 100,000,000 km2 (39,000,000 sq mi), about one-fifth of the Earth's surface. It fused with Euramerica during the Carboniferous to form Pangea a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras.

It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million years ago, and began to break apart about 200 million years ago, at the end of the Triassic and beginning of the Jurassic. In contrast to the present Earth and its distribution of continental mass, Pangaea was centered on the equator and surrounded by the superocean Panthalassa and the Paleo-Tethys and subsequent Tethys Oceans. Pangaea is the most recent supercontinent to have existed and the first to be reconstructed by geologists.

It began to separate from northern Pangea (Laurasia) during the Triassic, and started to fragment during the Early Jurassic (around 180 million years ago). The final stages of break-up, involving the separation of Antarctica from South America (forming the Drake Passage) and Australia, occurred during the Paleogene (from around 66 to 23 million years ago (Mya). Gondwana was not considered a supercontinent by the earliest definition, since the landmasses of Baltica, Laurentia, and Siberia were separated from it. To differentiate it from the Indian region of the same name (see ¤ Name), it is also commonly called Gondwanaland.

The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, Zealandia, Arabia, and the Indian Subcontinent.

Regions that were part of Gondwana shared floral and zoological elements that persist to the present day.

Mysterious Pink Sands in Australia Reveal Hidden Antarctic Mountains Science Alert - June 22, 2024

Joining the dots with ice-flow indicators in the South Australian glacial sedimentary rocks that garnet-rich glacial sands were ground out of the Antarctic mountains - which are yet to see the light of day - by an ice sheet moving north-west during the Late Palaeozoic Ice Age, when Australia and Antarctica were connected in supercontinent Gondwana.

The Pacific Is Destined to Vanish as Earth's Continents Meld Into a New Supercontinent Science Alert - October 5, 2022

The Pacific Ocean's days are numbered, according to a new supercomputer simulation of Earth's ever-drifting tectonic plates. The good news? Our planet's oldest ocean still has another 300 million years to go. If the Pacific gets lucky, it might even celebrate its billionth birthday before finally trickling out of existence.

Oldest Land-Living Animal from Gondwana Found Science Daily - September 3, 2013

Early life was confined to the sea and the process of terrestrialization - the movement of life onto land - began during the Silurian Period roughly 420 million years ago. The first wave of life to move out from water onto land consisted of plants, which gradually increased in size and complexity throughout the Devonian Period. This initial colonization of land was closely followed by plant and debris-eating invertebrate animals such as primitive insects and millipedes. By the end of the Silurian period about 416 million years ago, predatory invertebrates such as scorpions and spiders were feeding on the earlier colonists of land.

The lost continent of Zealandia hides clues to the Ring of Fire's birth Live Science - February 11, 2020

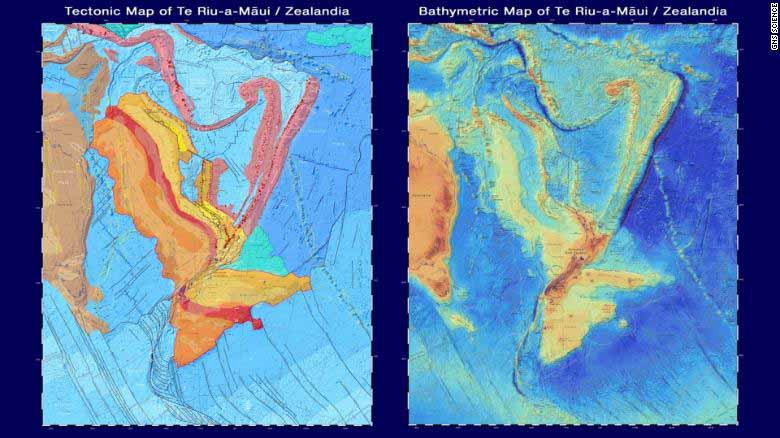

The hidden undersea continent of Zealandia underwent an upheaval at the time of the birth of the Pacific Ring of Fire. Zealandia is a chunk of continental crust next door to Australia. It's almost entirely beneath the ocean, with the exception of a few protrusions, like New Zealand and New Caledonia. But despite its undersea status, Zealandia is not made of magnesium- and iron-rich oceanic crust. Instead, it is composed of less-dense continental crust. The existence of this odd geology has been known since the 1970s, but only more recently has Zealandia been more closely explored. In 2017, geoscientists reported in the journal GSA Today that Zealandia qualifies as a continent in its own right, thanks to its structure and its clear separation from the Australian continent.

Earth is splitting open beneath the Pacific Northwest. Earth's tectonic engine is tearing itself apart, and scientists just caught it in the act. Science Daily - October 25, 2025

For the first time, scientists have seen a subduction zone actively breaking apart beneath the Pacific Northwest. Seismic data show the oceanic plate tearing into fragments, forming microplates in a slow, step-by-step collapse. This process, once only theorized, explains mysterious fossil plates found elsewhere and offers new clues about earthquake risks. The dying subduction zone is revealing Earth's tectonic life cycle in real time.

The geology that holds up the Himalayas - the world's highest mountain range and home to Mount Everest - is not what we thought, scientists discover Live Science - September 1, 2025

A new study reveals there is a piece of mantle sandwiched between the Asian and Indian crusts. This explains why the Himalayas grew so tall, and how they still remain so high today,

Lake Superior rocks reveal build up to giant collision that formed supercontinent Rodinia Live Science - August 20, 2025

Using paleomagnetic samples collected along the shores of Lake Superior, a new study illuminates the movement of a billion-year-old paleocontinent as it crept south toward a tectonic collision.

'Hot Blob' Heading For New York Following Ancient Greenland Rift. A vast blob of hot rock moving slowly beneath the Appalachian Mountains in the northeastern US is now thought to be the result of a divorce between Greenland and Canada some 80 million years ago. Science Alert - August 5, 2025

A vast blob of hot rock moving slowly beneath the Appalachian Mountains in the northeastern US is now thought to be the result of a divorce between Greenland and Canada some 80 million years ago. A study by an international team of researchers challenges the existing consensus in both geographical and chronological terms. It was previously thought the breaking up of the North American and African continents was responsible, some 180 million years ago.

2025 Kamchatka Peninsula Earthquake Wikipedia

Tsunami waves hit US shores after 8.8 magnitude quake strikes Russia's far east - 6th most powerful ever recorded CNN - July 30, 2025

Tsunami reaches Hawaii and California as earthquake off Russia triggers evacuations across Pacific BBC - July 30, 2025

The region is known for seismic activity due to its location in the Pacific Ring of Fire - a belt in the Pacific where the world's most active volcanoes are located. Russian volcano explodes in 'powerful' eruption, likely intensified by 8.8 magnitude earthquake Live Science - July 30, 2025

Aftershocks are expected to continue for some time, though decreasing in frequency and magnitude.

The 8.8 pacific earthquake could have affected this predicted event ... Undersea Volcano Off The US West Coast Predicted To Erupt In 2025

A volcano on Russia's far eastern Kamchatka Peninsula erupted overnight into Sunday for what scientists said is the first time in hundreds of years and days after the massive 8.8-magnitude earthquake last week PhysOrg - August 4, 2025

The eruption was accompanied by a 7.0-magnitude earthquake and prompted a tsunami warning for three areas of Kamchatka. The tsunami warning was later lifted by Russia's Ministry for Emergency Services.

Earth Is Pulsing Beneath Africa Where The Crust Is Being Torn Apart Science Alert - June 25, 2025

A deep, rhythmic pulse has been found surging like a heartbeat deep under Africa. At the Afar triple junction under Ethiopia, where three tectonic plates meet, molten magma pounds the planet's crust from below, scientists have discovered. There, the continent is slowly being torn asunder in the early formation stages of a new ocean basin. By sampling the chemical signatures of volcanoes around this region, a team led by geologist Emma Watts of Swansea University in the UK hoped to learn more about this wild process.

Researchers have found fresh evidence that Africa is breaking apart because of a deep mantle superplume of hot rock beneath the East African Rift System Live Science - May 28, 2025

Researchers have found new evidence that a gigantic superplume of hot rock is rising beneath Africa, causing intense volcanic activity and splitting the continent in two. Geologists have long known that Africa is slowly breaking apart in a region called the East African Rift System (EARS), but the driving force behind this massive geological process was up for debate. Now, a new study has presented geochemical evidence that a previously theorized superplume is pressing up against - and fracturing - the African crust. Scientists found that gases at the Meengai geothermal field in central Kenya have a chemical signature that comes from deep inside Earth's mantle, likely from between the bottom of the mantle and the core. The signature matches those of gases found in volcanic rocks to the north, in the Red Sea, and to the south, in Malawi, indicating all of these places are sitting on the same deep mantle rock, according to a statement from the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

This article about plate tectonics totally connected for me. It's the place where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers meet - a mountain range that starts with the letter "Z" - the Cradle of Civilization - and the first landing place of the Anunnaki when Earth was terraformed.

Ancient Oceanic Plate Rips Apart Beneath Iraq and Iran. In the past sediments eroded from the Zagros mountains forming plains such as Mesopotamia. SciTech Daily - February 4, 2025

https://www.livescience.com/planet-earth/geology/ocean-plate-from-time-of-pangaea-is-now-being-torn-apart-under-iraq-and-iran Live Science - February 8, 2025

Unexpected And Unexplained Structures Found Deep Below The Pacific Ocean Live Science - January 8, 2025

Geoscientists have used earthquakes to study the composition of the lower portion of the EarthÕs mantle under the Pacific Ocean Š and they've discovered something quite peculiar. There are zones where the seismic waves move in different ways, suggesting structures that are colder or have a different composition than the surrounding molten rocks. The team describes the presence of these structures as a major mystery. It is unclear what these structures are. If they were anywhere else, they could be portions of tectonic plates that have sunk in a subduction zone. But the Pacific is one large plate, so there should be no subduction material under it. The researchers are also uncertain about what kind of material these deep structures are made of or what this means for the internal structure of the planet.

Tristan da Cunha: The most remote inhabited island on Earth, forged from a supercontinent breakup Live Science - January 3, 2025

Tristan da Cunha is a group of islands in the South Atlantic that formed from the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana. Today, it's home to a tiny and extremely isolated farming community.

Denali Fault found to have torn apart ancient joining of two landmasses PhysOrg - December 21, 2024

New research shows that three sites spread along an approximately 620-mile portion of today's Denali Fault were once a smaller united geologic feature indicative of the final joining of two land masses. That feature was then torn apart by millions of years of tectonic activity.

Geologists discover mysterious subduction zone beneath Pacific, reshaping understanding of Earth's interior PhysOrg - September 29, 2024

Scientists uncovered evidence of an ancient seafloor that sank deep into Earth during the age of dinosaurs, challenging existing theories about Earth's interior structure. Located in the East Pacific Rise (a tectonic plate boundary on the floor of the southeastern Pacific Ocean), this previously unstudied patch of seafloor sheds new light on the inner workings of our planet and how its surface has changed over millions of years.

Mesmerizing animation shows Earth's tectonic plates moving from 1.8 billion years ago to today Live Science - September 10, 2024

Video Watch 1.8 Billion Years Of Earth's Moving Tectonic Plates In Just 1 Minute IFL Science - September 10, 2024

Researchers have discovered the world's oldest known arc-slicing fault in Australia, intensifying the debate over the origins of plate tectonics Live Science - August 7, 2024

Scientists may have discovered the world's oldest arc-slicing fault in Northwestern Australia's remote deserts. The finding demonstrates that plate tectonic processes were operational at least 3 billion years ago, fueling the ongoing scientific debate. Plate tectonics, the theory that underpins Earth's geological activity, shapes our planet with mountains, shifting continents, and seismic upheavals. Yet pinpointing the origins of this fundamental process remains a contentious debate.

2,000 earthquakes in 1 day off Canada coast suggest the ocean floor is ripping apart, scientists say. Record earthquake activity off the coast of Vancouver Island hints at the birth of new oceanic crust Live Science - March 23, 2024

Intense Seismic Shakes Off Canada's Coast May Be Forming New Seafloor. Over 200 earthquakes per hour have recently been recorded offshore of Vancouver Island IFL Science - March 23, 2024

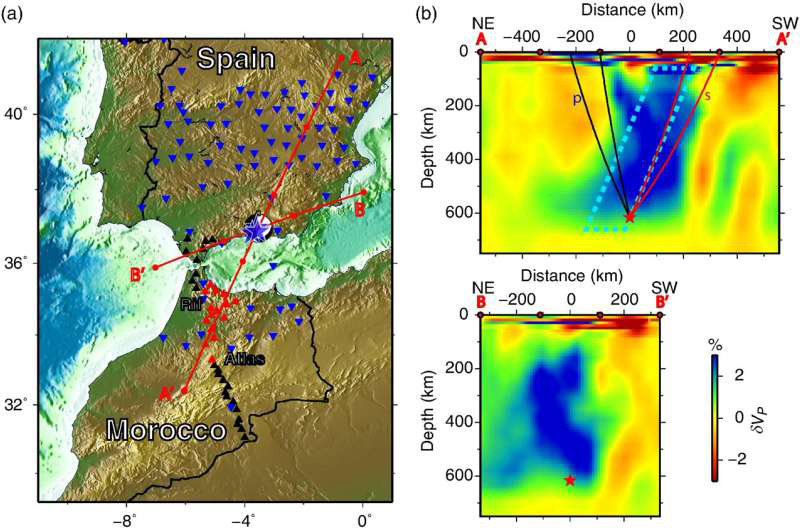

Strange seismic wave arrivals lead to discovery of overturned slab in the Mediterranean PhysOrg - February 24, 2024

Strange seismic wave arrivals from a 2010 earthquake under Spain were the clues that led to an unexpected discovery beneath the western Mediterranean: a subducted oceanic slab that has completely overturned.

The Atlantic Ocean Could Be Developing Its Own "Ring Of Fire" IFL Science - February 19, 2024

The dance of the continents could be about to take a new turn, with the Atlantic moving from a growth to a contraction phase. This, some geologists predict, will be caused by the breaking of tectonic plates, causing lines of volcanoes along the coastlines of Africa and Iberia. Over billions of years, the EarthÕs continents have repeatedly come together and come apart. There is no doubt this will happen again; what is uncertain is the timing and whether most continents will collect at the North Pole or the equator.

Geoscientists find Pacific plate is scored by large undersea faults that are pulling it apart PhysOrg - February 6, 2024

A team of geoscientists is shedding new light on the century-old model of plate tectonics, which suggests the plates covering the ocean floors are rigid as they move across the Earth's mantle. Researchers found that the Pacific plate is scored by large undersea faults that are pulling it apart

Indian Tectonic Plate Is Splitting in Two Beneath Tibet, Latest Analysis Finds Science Alert - January 17, 2024

Combined with a fresh look at previous research, a recent analysis of new seismic data collected from across southern Tibet has delivered a surprising depiction of the titanic forces operating below the Himalayas. Presenting at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco last December, researchers from institutions in the US and China described a disintegration of the Indian continental plate as it grinds along the basement of the Eurasian tectonic plate that sits atop it.

Scientists discover ghost of ancient mega-plate that disappeared 20 million years ago Live Science - October 12, 2023

A long-lost tectonic plate dubbed 'Pontus' that was a quarter of the size of the Pacific Ocean was discovered by chance by scientists studying ancient rocks in Borneo.

Fountains of diamonds erupt from Earth's center as supercontinents break up Live Science - August 20, 2023

Researchers have discovered a pattern where diamonds spew from deep beneath Earth's surface in huge, explosive volcanic eruptions.

Volcanoes like Kilauea and Mauna Loa don't erupt like we thought they did, scientists discover Live Science - August 9, 2023

Volcanoes that sit within Earth's tectonic plates don't erupt how scientists thought they did. It turns out, magma within these volcanoes is propelled up and out of the ground by carbon dioxide - not by water, as was previously thought, a new study finds. This magma also shoots up from much deeper reserves than previously estimated, originating in Earth's mantle at depths of 12 to 19 miles (20 to 30 kilometers), rather than in the outer crust, 4 to 8 miles (7 to 13 km) deep.

New geology study cracks the code of what causes diamonds to erupt PhysOrg - July 27, 2023

We've Discovered How Diamonds Make Their Way To The Surface And It May Tell Us Where To Find Them IFL Science - July 27, 2023

New research, carried out by researchers in a variety of countries and published in Nature, suggests that diamonds may be a sign of break up too - of Earth's tectonic plates, that is. It may even provide clues to where is best to go looking for them. Diamonds, being the hardest naturally-occurring stones, require intense pressures and temperatures to form. These conditions are only achieved deep within the Earth. So how do they get from deep within the Earth, up to the surface? Diamonds are carried up in molten rocks, or magmas, called kimberlites. Until now, we didn't know what process caused kimberlites to suddenly shoot through the Earth's crust having spent millions, or even billions, of years stowed away under the continents.

Africa Is Splitting Into Two And New Data Is Uncovering How IFL Science - August 19, 2023

The feature in question is the East African Rift System (EARS), an active continental rift zone that stretches downward for thousands of kilometers from roughly north to south through Ethiopia, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Tanzania, Malawi, and Mozambique. The EARS is effectively a crack in the African plate that could split the continent into two plates - the smaller Somalian plate and the larger Nubian plate. The two sides are drifting apart from each other at a super-sluggish snail's pace of millimeters per year, less than the rate your fingernails grow. At this rate, it won't be for millions and millions of years until the potential break-up occurs. That said, we're already witnessing the impact of the EARS since it's seismically active. At points where the lithosphere is stretched especially thin, giant cracks in the ground can form and earthquakes are frequently sparked.

Is Africa splitting into two continents? Live Science - June 17, 2023

A giant rift is slowly tearing Africa, the second-largest continent, apart. This depression - known as the East African Rift - is a network of valleys that stretches about 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) long, from the Red Sea to Mozambique.ill Africa rip apart completely, and if so, when will it split? To answer this question, let's look at the region's tectonic plates, the outer parts of the planet's surface that can collide with each other, making mountains, or pull apart, creating vast basins. Along this colossal tear in eastern Africa, the Somalian tectonic plate is pulling eastward from the larger, older part of the continent, the Nubian tectonic plate, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. (The Somalian plate is also known as the Somali plate, and the Nubian plate is also sometimes called the African plate.)

Scientists find weird holes on the ocean floor spewing ancient fluids like a fire hose at the bottom of the ocean off the coast of Oregon Live Science - April 24, 2023

Understanding the movement of fluids in the Cascadia subduction zone can help researchers pinpoint the risk of earthquakes. Holes spewing warm fluids from the boundary between tectonic plates have been discovered at the bottom of the ocean off the coast of Oregon. Researchers think this strange, never-before-seen phenomenon, dubbed Pythia's Oasis after an ancient Greek priestess, could provide insight into earthquake risk along the dangerous fault - although exactly how it affects the tectonics is unclear.

Extreme 'Rogue Wave' in The North Pacific Confirmed as Most Extreme on Record Science Alert - January 12, 2023

In November of 2020, a freak wave came out of the blue, lifting a lonesome buoy off the coast of British Columbia 17.6 meters high (58 feet). The four-story wall of water was finally confirmed in February 2022 as the most extreme rogue wave ever recorded.

Wild New Paper Suggests Earth's Tectonic Activity Has an Unseen Source Science Alert - January 26, 2022

A newly published study looks to the skies for an explanation. Noting that force rather than heat is most commonly used to move large objects, the authors suggest that the interplay of gravitational forces from the Sun, Moon, and Earth could be responsible for the movement of Earth's tectonic plates.

Plate tectonics are 3.6 billion years old, oldest minerals on Earth reveal - zircon crystals Live Science - May 17, 2021

Earth's tectonic plates have moved continuously since they emerged a whopping 3.6 billion years ago, according to a new study on some of the world's oldest crystals. Previously, researchers thought that these plates formed anywhere from 3.5 billion to 3 billion years ago, and yet-to-be published research even estimated that the plates are 3.7 billion years old. The scientists on the new study discovered the onset date of plate tectonics by analyzing ancient zircon crystals from the Jack Hills in Western Australia. Some of the zircons date to 4.3 billion years ago, meaning they existed when Earth was a mere 200 million years old - a baby, geologically speaking. Researchers used these zircons, as well as younger ones dating to 3 billion years ago, to decipher the planet's ongoing chemical record.

Earth's oldest minerals date onset of plate tectonics to 3.6 billion years ago PhysOrg - May 15, 2021

Earth is the only planet known to host complex life and that ability is partly predicated on another feature that makes the planet unique: plate tectonics. No other planetary bodies known to science have Earth's dynamic crust, which is split into continental plates that move, fracture and collide with each other over eons. Plate tectonics afford a connection between the chemical reactor of Earth's interior and its surface that has engineered the habitable planet people enjoy today, from the oxygen in the atmosphere to the concentrations of climate-regulating carbon dioxide. But when and how plate tectonics got started has remained mysterious, buried beneath billions of years of geologic time.

Watch a Billion Years of Shifting Tectonic Plates in 40 Mesmerizing Seconds Science Alert - February 9, 2021

The tectonic plates that cover Earth like a jigsaw puzzle move about as fast as our fingernails grow, but over the course of a billion years that's enough to travel across the entire planet - as a fascinating new video shows.

The Atlantic Ocean is widening. Here's why. Live Science - January 28, 2021

The Atlantic Ocean is getting wider, shoving the Americas to one side and Europe and Africa to the other. But it's not known exactly how. A new study suggests that deep beneath the Earth's crust, in a layer called the mantle, sizzling-hot rocks are rising up and pushing on tectonic plates - those rocky jigsaw pieces that form Earth's crust - that meet beneath the Atlantic. Previously, scientists thought that the continents were mostly being pulled apart as the plates beneath the ocean moved in opposite directions and crashed into other plates, folding under the force of gravity. But the new study suggests that's not the whole picture. The research began in 2016, when a group of researchers set sail on a research vessel to the widest part of the Atlantic Ocean between South America and Africa; in other words, to the middle of nowhere.

'Lost' tectonic plate called Resurrection hidden under the Pacific Live Science - October 22, 2020

Scientists have reconstructed a long-lost tectonic plate that may have given rise to an arc of volcanoes in the Pacific Ocean 60 million years ago. The plate, dubbed Resurrection, has long been controversial among geophysicists, as some believe it never existed. But the new reconstruction puts the edge of the rocky plate along a line of known ancient volcanoes, suggesting that it was once part of the crust (Earth's top layer) in what is today northern Canada.

A new idea on how Earth's outer shell first broke into tectonic plates PhysOrg - July 20, 2020

The activity of the solid Earth - for example, volcanoes in Java, earthquakes in Japan, etc. - is well understood within the context of the ~50-year-old theory of plate tectonics. This theory posits that Earth's outer shell (Earth's "lithosphere") is subdivided into plates that move relative to each other, concentrating most activity along the boundaries between plates. It may be surprising, then, that the scientific community has no firm concept on how plate tectonics got started.

The African continent is very slowly peeling apart. Scientists say a new ocean is being born NBC - July 19, 2020

In one of the hottest places on Earth, along an arid stretch of East Africa's Afar region, it's possible to stand on the exact spot where, deep underground, the continent is splitting apart. This desolate expanse sits atop the juncture of three tectonic plates that are very slowly peeling away from each other, a complex geological process that scientists say will eventually cleave Africa in two and create a new ocean basin millions of years from now. For now, the most obvious evidence is a 35-mile-long crack in the Ethiopian desert.

Maps reveal new details about New Zealand's lost underwater continent CNN - June 23, 2020

Under New Zealand, there lies a vast continent on the sea floor. Once part of the same land mass as Antarctica and Australia, the lost continent of Zealandia broke off 85 million years ago and eventually sank below the ocean, where it stayed largely hidden for centuries. Now, maps reveal new research about the underwater continent where dinosaurs once roamed - and allow the public to virtually explore it. GNS Science, a New Zealand research institute, published two new maps and an interactive website on Monday. The maps cover the shape of the ocean floor and Zealandia's tectonic profile, which collectively help tell the story of the continent's origins.

Giant tectonic plate under Indian Ocean is breaking in two Live Science - May 22, 2020

In a short time (geologically speaking) this plate will split in two, a new study finds.

How the Earth's last supercontinent broke apart to form the world we have today BBC - May 14, 2020

Pangaea was the Earth's latest supercontinent-a vast amalgamation of all the major landmasses. Before Pangaea began to disintegrate, what we know today as Nova Scotia was attached to what seems like an unlikely neighbor: Morocco. Newfoundland was attached to Ireland and Portugal.

We Could Be Witnessing the Death of a Tectonic Plate, Says Earth Scientist Live Science - August 7, 2019

A gaping hole in a dying tectonic plate beneath the ocean along the West Coast of the United States may be wreaking havoc at Earth's surface, but not in a way most people might expect. This gash is so big it may trigger earthquakes off the coast of Northern California and could explain why central Oregon has volcanoes, a new study found. The researchers in the new study aren't the first to suggest that the Michigan-size Juan de Fuca (pronounced "wahn de fyoo-kuh") plate has a tear. But thanks to a new, detailed dataset, they're the first to say so with certainty.

Plate tectonics that control the movement of the continents and cause earthquakes first formed 2.5 billion years ago, scientists claim Daily Mail - August 7, 2019

Plate tectonics, the gradual drift of continents across the Earth's surface that causes earthquake, began around 2.5 billion years ago, a new study suggests. Exactly when the Earth's plates formed and began moving has long been a subject of debate, with estimates ranging from 3.5-5 billion years ago. Researchers studied metamorphic rocks from across the globe to build up a picture of how the heat flow in the Earth's crust has changed over time. From this they were able to determine when plate tectonics must have first begun.

A rocky relationship: A history of Earth's continents breaking up and getting back together PhysOrg - August 7, 2019

A new study of rocks that formed billions of years ago lends fresh insight into how Earth's plate tectonics, or the movement of large pieces of Earth's outer shell, evolved over the planet's 4.56-billion-year history. A report of the findings reveals that, contrary to previous studies that say plate tectonics has operated throughout Earth's history or that it emerged only 0.7 billion years ago, plate tectonics actually evolved over the last 2.5 billion years. This new timeline impacts researchers' models for understanding how Earth has changed.

A Tiny Magma Blob May Rewrite Earth's History of Plate Tectonics Live Science - August 7, 2019

A blob of magma entombed in a bubble smaller than the width of a human hair and found in South Africa may turn back the clock on Earth's first slow dance of the rocky slabs that make up its outer shell. The chemicals inside that little blob suggest so-called plate tectonics revved up during the first billion years of Earth's existence. Since the 1950s, scientists have known Earth's crust is made of giant slabs called tectonic plates that float above Earth's molten mantle. These colossal plates meet in subduction zones, where the lighter slab slides under the heavier one into the depths of the mantle. The sinking crust, infused with minerals collected from Earth's surface, melts into magma under the extreme pressures and temperatures of Earth's interior

Did plate tectonics set the stage for life on Earth? PhysOrg - June 7, 2018

A new study suggests that rapid cooling within the Earth's mantle through plate tectonics played a major role in the development of the first life forms, which in turn led to the oxygenation of the Earth's atmosphere. Scientists found that over the 4.5 billion years of the Earth's development, rocks rich in phosphorus accumulated in the Earth's crust. They then looked at the relationship of this accumulation with that of oxygen in the atmosphere.

Geoscientists suggest 'snowball Earth' resulted from plate tectonics PhysOrg - May 7, 2018

About 700 million years ago, the Earth experienced unusual episodes of global cooling that geologists refer to as "Snowball Earth." Several theories have been proposed to explain what triggered this dramatic cool down, which occurred during a geological era called the Neoproterozoic. Now geologists suggest that those major climate changes can be linked to one thing: the advent of plate tectonics. Plate tectonics is a theory formulated in the late 1960s that states the Earth's crust and upper mantle - a layer called the lithosphere - is broken into moving pieces, or plates. These plates move very slowly - about as fast as your fingernails and hair grow - causing earthquakes, mountain ranges and volcanoes.

Big crack is evidence that East Africa could be splitting in two CNN - April 5, 2018

A large crack, stretching several kilometres, made a sudden appearance recently in south-western Kenya. The tear, which continues to grow, caused part of the Nairobi-Narok highway to collapse and was accompanied by seismic activity in the area. The Earth is an ever-changing planet, even though in some respects change might be almost unnoticeable to us. Plate tectonics is a good example of this. But every now and again something dramatic happens and leads to renewed questions about the African continent splitting in two. The Earth's lithosphere (formed by the crust and the upper part of the mantle) is broken up into a number of tectonic plates. These plates are not static, but move relative to each other at varying speeds, "gliding" over a viscous asthenosphere.

1.7-Billion-Year-Old Chunk of North America Found Sticking to Australia Live Science - January 22, 2018

Geologists matching rocks from opposite sides of the globe have found that part of Australia was once attached to North America 1.7 billion years ago. Researchers from Curtin University in Australia examined rocks from the Georgetown region of northern Queensland. The rocks - sandstone sedimentary rocks that formed in a shallow sea - had signatures that were unknown in Australia but strongly resembled rocks that can be seen in present-day Canada. The researchers, who described their findings online Jan. 17 in the journal Geology, concluded that the Georgetown area broke away from North America 1.7 billion years ago. Then, 100 million years later, this landmass collided with what is now northern Australia, at the Mount Isa region.

Study bolsters theory of heat source under Antarctica PhysOrg - November 8, 2017

A new NASA study adds evidence that a geothermal heat source called a mantle plume lies deep below Antarctica's Marie Byrd Land, explaining some of the melting that creates lakes and rivers under the ice sheet. Although the heat source isn't a new or increasing threat to the West Antarctic ice sheet, it may help explain why the ice sheet collapsed rapidly in an earlier era of rapid climate change, and why it is so unstable today.

Earth's tectonic plates are weaker than once thought PhysOrg - October 3, 2017

No one can travel inside the earth to study what happens there. So scientists must do their best to replicate real-world conditions inside the lab.

Analysis of titanium in ancient rocks creates upheaval in history of early Earth PhysOrg - September 22, 2017

The Earth's history is written in its elements, but as the tectonic plates slip and slide over and under each other over time, they muddy that evidence - and with it the secrets of why Earth can sustain life.

Tectonic plates 'weaker than previously thought,' say scientists PhysOrg - September 14, 2017

Experiments carried out at Oxford University have revealed that tectonic plates are weaker than previously thought. The finding explains an ambiguity in lab work that led scientists to believe these rocks were much stronger than they appeared to be in the natural world. This new knowledge will help us understand how tectonic plates can break to form new boundaries.

Space view of Earth's magnetic rocks BBC - March 21, 2017

It is the best depiction yet of the magnetism retained in Earth's rocks, as viewed from space.

The map was constructed using data from Europe's current Swarm mission, combined with legacy information from a forerunner satellite called Champ. Variations as small as 250km across are detectable. Clearly seen are the "stripes" of magnetism moving away from mid-ocean ridges - the places on the planet where new crust is constantly produced. This pattern - the consequence of periodic changes in Earth's polarity being locked into the minerals of cooling volcanic rock - was one of the key pieces of evidence for the theory of plate tectonics.

Release of water shakes Pacific Plate at depth PhysOrg - January 11, 2017

Tonga is a seismologists' paradise, and not just because of the white-sand beaches. The subduction zone off the east coast of the archipelago racks up more intermediate-depth and deep earthquakes than any other subduction zone, where one plate of Earth's lithosphere dives under another, on the planet. Tonga is such an extreme place, and that makes it very revealing. That swarm of earthquakes is catnip for seismologists because they still don't understand what causes earthquakes to pop off at such great depths.

New Seafloor Map Reveals Secrets of Ancient Continents' Shoving Match Live Science - January 20, 2016

Tectonic plates may have inched across the Earth's surface to where they are now over the course of billions of years, but they left behind traces of this movement in bumps and gashes under the sea. Now, a new topographic map of the seafloor has helped researchers chronicle when the Indian-Eurasian continent formed as well as find a previously undiscovered microplate that broke off as a result of the event. NASA's Earth Observatory released the map on Jan. 13, and it reveals the complex topography of the planet's seafloor. By analyzing these underwater peaks and ridges, researchers can decipher how and when the plates that made up the ancient supercontinent Pangaea tore apart about 200 million years ago, resulting in the birth of new ocean crust and the formation of mountain ranges. The map, which is bright blue and red like a heat map, was compiled by an international team of researchers using a gravity model of the ocean, which is in turn based on altimetry data from the CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 satellites.

Continents Rose Above Oceans 3 Billion Years Ago Live Science - June 27, 2015

The continents may have first risen high above the oceans of the world about 3 billion years ago, researchers say. That's about a billion years earlier than geoscientists had suspected for the emergence of a good chunk of the continents. Earth is the only known planet whose surface is divided into continents and oceans. Currently, the continents rise an average of about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) above the seafloor. The continents are composed of a thick, buoyant crust that's about 21 miles (35 km) deep, on average, whereas the comparatively thin, dense crust of the ocean floor is only an average of about 4 miles (7 km) thick. Because the continents are so thick and buoyant, they are less likely to get dragged downward. That's why so many ancient continental rocks have survived in the Earth's crust. Still, much about the earliest days of continents, and when and how they formed, remains hotly contested.

Uplifted island PhysOrg - June 22, 2015

The island Isla Santa Mar’a in the south of central Chile is the document of a complete seismic cycle. At the South American west coastline the Pacific Ocean floor moves under the South American continent. Resulting that through an in- and decrease of tension the earth's crust along the whole continent from Tierra del Fuego to Peru broke alongside the entire distance in series of earthquakes within one and a half century. The earthquake of 1835 was the beginning of such a seismic cycle in this area. After examining the results of the Maule earthquake in 2010 a team for the first time were able to measure and simulate a complete seismic cycle at its vertical movement of the earth's crust at this place.

North American plate shattered speed records a billion years ago PhysOrg - February 4, 2015

A new study led by Michigan Technological University geophysicist Aleksey Smirnov reveals that 1.1 billion years ago, the North American tectonic plate scooted along at a blistering 24.6 centimeters - about 10 inches - per year. While it may not seem to be shattering any speed records, that's twice as fast as continental plates typically traveled in their wanderings over the earth's surface back in Precambrian times. Oceanic plates moved that quickly, but they are also much thinner, only 10 to 15 kilometers deep. Continental plates are up to 70 kilometers (43 miles) thick. These days, tectonic plates - 15-20 huge, interlocking pieces that make up the earth's crust - are even slower. Nevertheless, their movements are partially responsible for geological phenomena like earthquakes, volcanoes and mountain building.

Breakup of ancient supercontinent Pangea hints at future fate of Atlantic Ocean PhysOrg - December 1, 2014

Pangea, the supercontinent that contained most of the Earth's landmass until about 180 million years ago, endured an apocalyptic undoing during the Jurassic period, when the Atlantic Ocean opened up. This is well understood. But what is less clear is how Pangea came into being in the first place.

Tectonic plates not rigid, deform horizontally in cooling process Science Daily - November 5, 2014

The puzzle pieces of tectonic plates are not rigid and don't fit together as nicely as we were taught in high school. A new study quantifies deformation of the Pacific plate and challenges the central approximation of the plate tectonic paradigm that plates are rigid. Oceanic tectonic plates deform due to cooling, causing shortening of the plates and mid-plate seismicity.

Pacific plate shrinking as it cools Science Daily - August 28, 2014

The Pacific tectonic plate is not as rigid as scientists believe, according to new calculations. Scientists have determined that cooling of the lithosphere -- the outermost layer of Earth -- makes some sections of the Pacific plate contract horizontally at faster rates than others and cause the plate to deform. The tectonic plates that cover Earth's surface, including both land and seafloor, are in constant motion; they imperceptibly surf the viscous mantle below. Over time, the plates scrape against and collide into each other, forming mountains, trenches and other geological features. The new calculations showed the Pacific plate is pulling away from the North American plate a little more -- approximately 2 millimeters a year -- than the rigid-plate theory would account for, he said. Overall, the plate is moving northwest about 50 millimeters a year.

From Drip to Glide: How Plate Tectonics Started Live Science - April 7, 2014

A cold, crusty shell of a planet that regularly kills off its occupants with violent earthquakes and massive volcanic eruptions doesn't sound like ideal habitat. But Earth's grinding plates, the source of its deadly tectonics, are actually one of the key ingredients that make it only planet with life in the solar system (found so far). Now, a new model seeks to explain why Earth's plate tectonics is unique among the sun's rocky planets. It all comes down to tiny minerals in rocks.

Why Is Africa Ripping Apart? Seismic Scan May Tell Live Science - June 19, 2013

Arrays of sensors stretching across more than 1,500 miles in Africa are now probing the giant crack in the Earth located there - a fissure linked with human evolution - to discover why and how continents get ripped apart. Over the course of millions of years, Earth's continents break up as they are slowly torn apart by the planet's tectonic forces. All the ocean basins on the Earth started as continental rifts, such as the Rio Grande rift in North America and Asia's Baikal rift in Siberia. The giant rift in Eastern Africa was born when Arabia and Africa began pulling away from each other about 26 million to 29 million years ago. Although this rift has grown less than 1 inch (2.54 centimeters) per year, the dramatic results include the formation and ongoing spread of the Red Sea, as well as the East African Rift Valley, the landscape that might have been home to the first humans.

CONTINENTAL DRIFT