Photography has a long history going back to ancient civilizations. As with everything else it continues to evolve in the type of equipment used allowing even the novice to create a captivating photo.

Photography has contributed both physical and paranormal images (spirit photography) including ghosts and apparitions particularly of Mother Mary - no matter what type of camera was used. It awakens the imagination to search for something beyond physical reality with a desire to find out what lies beyond what our eyes show us.

Today we are dependent on film and photography for many things from helping us understand how things work to surveillance in crime solving to the creation of special effects which stir the imagination and awaken memory of the fact that physical reality itself is projected illusion in a simulation - two dimensional sheets or images that become what we embrace as physical reality.

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating durable images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is employed in many fields of science, manufacturing (e.g., photolithography), and business, as well as its more direct uses for art, film and video production, recreational purposes, hobby, and mass communication.

Typically, a lens is used to focus the light reflected or emitted from objects into a real image on the light-sensitive surface inside a camera during a timed exposure. With an electronic image sensor, this produces an electrical charge at each pixel, which is electronically processed and stored in a digital image file for subsequent display or processing. The result with photographic emulsion is an invisible latent image, which is later chemically "developed" into a visible image, either negative or positive, depending on the purpose of the photographic material and the method of processing. A negative image on film is traditionally used to photographically create a positive image on a paper base, known as a print, either by using an enlarger or by contact printing.

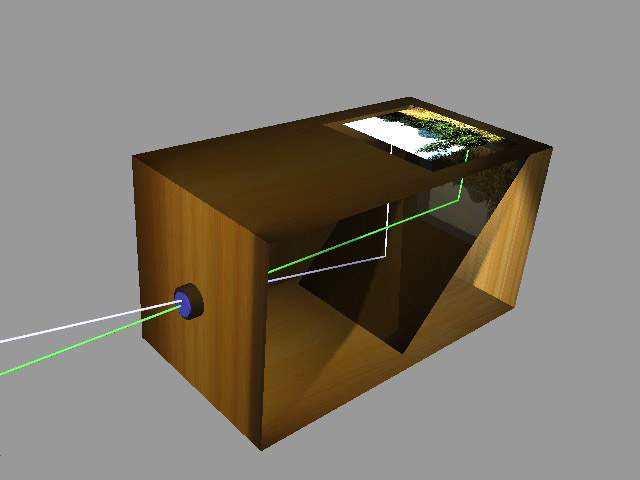

Photography is the result of combining several technical discoveries, relating to seeing an image and capturing the image. The discovery of the camera obscura ("dark chamber" in Latin) that provides an image of a scene dates back to ancient China. Greek mathematicians Aristotle and Euclid independently described a camera obscura in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. In the 6th century CE, Byzantine mathematician Anthemius of Tralles used a type of camera obscura in his experiments.

The Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) (965-1040) also invented a camera obscura as well as the first true pinhole camera.The invention of the camera has been traced back to the work of Ibn al-Haytham. While the effects of a single light passing through a pinhole had been described earlier, Ibn al-Haytham gave the first correct analysis of the camera obscura, including the first geometrical and quantitative descriptions of the phenomenon and was the first to use a screen in a dark room so that an image from one side of a hole in the surface could be projected onto a screen on the other side. He also first understood the relationship between the focal point and the pinhole, and performed early experiments with afterimages, laying the foundations for the invention of photography in the 19th century.

Leonardo da Vinci mentions natural camerae obscurae that are formed by dark caves on the edge of a sunlit valley. A hole in the cave wall will act as a pinhole camera and project a laterally reversed, upside down image on a piece of paper. Renaissance painters used the camera obscura which, in fact, gives the optical rendering in color that dominates Western Art. It is a box with a small hole in one side, which allows specific light rays to enter, projecting an inverted image onto a viewing screen or paper.

The birth of photography was then concerned with inventing means to capture and keep the image produced by the camera obscura. Albertus Magnus (1193-1280) discovered silver nitrate, and Georg Fabricius (1516-1571) discovered silver chloride, and the techniques described in Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics are capable of producing primitive photographs using medieval materials.

Daniele Barbaro described a diaphragm in 1566. Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals (photochemical effect) in 1694. The fiction book Giphantie, published in 1760, by French author Tiphaigne de la Roche, described what can be interpreted as photography.

Around the year 1800, British inventor Thomas Wedgwood made the first known attempt to capture the image in a camera obscura by means of a light-sensitive substance. He used paper or white leather treated with silver nitrate. Although he succeeded in capturing the shadows of objects placed on the surface in direct sunlight, and even made shadow copies of paintings on glass, it was reported in 1802 that "the images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver." The shadow images eventually darkened all over.

Earliest known surviving heliographic engraving, 1825, printed from a metal plate made by Nicephore Niepce. The plate was exposed under an ordinary engraving and copied it by photographic means. This was a step towards the first permanent photograph taken with a camera. It is a reproduction of a 17th century Flemish engraving, showing a man leading a horse.

The first permanent photoetching was an image produced in 1822 by the French inventor Nicephore Niepce, but it was destroyed in a later attempt to make prints from it. Niepce was successful again in 1825. In 1826 or 1827, he made the View from the Window at Le Gras, the earliest surviving photograph from nature (i.e., of the image of a real-world scene, as formed in a camera obscura by a lens).

Because Niepce's camera photographs required an extremely long exposure (at least eight hours and probably several days), he sought to greatly improve his bitumen process or replace it with one that was more practical. In partnership with Louis Daguerre, he worked out post-exposure processing methods that produced visually superior results and replaced the bitumen with a more light-sensitive resin, but hours of exposure in the camera were still required. With an eye to eventual commercial exploitation, the partners opted for total secrecy.

The Daguerreotype was the first publicly available photographic process; it was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process. Invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839, the daguerreotype was almost completely superseded by 1860 with new, less expensive processes, such as ambrotype, that yield more readily viewable images. There has been a revival of the daguerreotype since the late 20th century by a small number of photographers interested in making artistic use of early photographic processes.

To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish; treated it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive; exposed it in a camera for as long as was judged to be necessary, which could be as little as a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or much longer with less intense lighting; made the resulting latent image on it visible by fuming it with mercury vapor; removed its sensitivity to light by liquid chemical treatment; rinsed and dried it; and then sealed the easily marred result behind glass in a protective enclosure.

The image is on a mirror-like silver surface and will appear either positive or negative, depending on the angle at which it is viewed, how it is lit and whether a light or dark background is being reflected in the metal. The darkest areas of the image are simply bare silver; lighter areas have a microscopically fine light-scattering texture. The surface is very delicate, and even the lightest wiping can permanently scuff it. Some tarnish around the edges is normal.

Tintype of two girls in front of a painted background of the Cliff House and Seal Rocks in San Francisco, circa 1900

Several types of antique photographs, most often ambrotypes and tintypes, but sometimes even old prints on paper, are commonly misidentified as daguerreotypes, especially if they are in the small, ornamented cases in which daguerreotypes made in the US and the UK were usually housed. The name "daguerreotype" correctly refers only to one very specific image type and medium, the product of a process that was in wide use only from the early 1840s to the late 1850s.

A tintype, also known as a melainotype or ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. Tintypes enjoyed their widest use during the 1860s and 1870s, but lesser use of the medium persisted into the early 20th century and it has been revived as a novelty and fine art form in the 21st.

Tintype portraits were at first usually made in a formal photographic studio, like daguerreotypes and other early types of photographs, but later they were most commonly made by photographers working in booths or the open air at fairs and carnivals, as well as by itinerant sidewalk photographers. Because the lacquered iron support (there is no actual tin used) was resilient and did not need drying, a tintype could be developed and fixed and handed to the customer only a few minutes after the picture had been taken.

The tintype photograph saw more uses and captured a wider variety of settings and subjects than any other photographic type of the period. It was introduced while the daguerreotype was still popular, though its primary competition would have been the ambrotype.

The tintype saw the Civil War come and go, documenting the individual soldier and horrific battle scenes. It captured scenes from the Wild West, as it was easy to produce by itinerant photographers working out of covered wagons.

It began losing artistic and commercial ground to higher quality albumen prints on paper in the mid-1860s, yet survived for well over another 40 years, living mostly as a carnival novelty. The tintype's immediate predecessor, the ambrotype, was done by the same process of using a sheet of glass as the support. The glass was either of a dark color or provided with a black backing so that, as with a tintype, the underexposed negative image in the emulsion appeared as a positive. Tintypes were sturdy and did not require mounting in a protective hard case like ambrotypes and daguerreotypes.

September 19, 2004

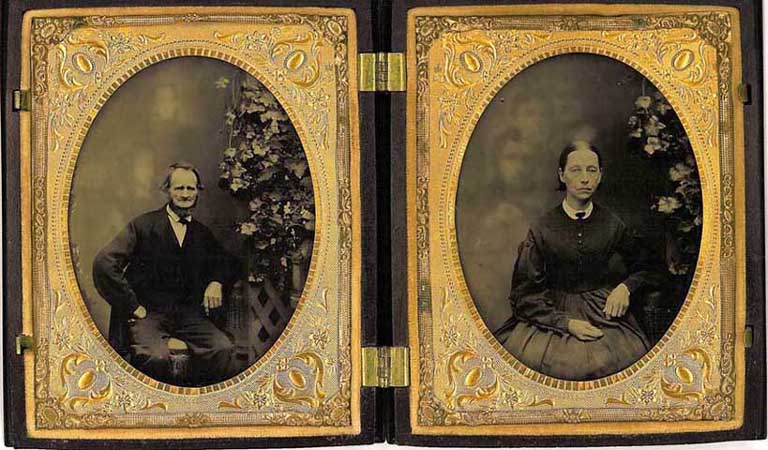

I received 2 photos from a reader named Debbie along with this information about them.

Ellie: The people in the photos are not my ancestors, so I don't know very much about them. I collect 19th Century photography. I purchased a box of photographs and letters passed down in a family for generations, and these were among them.

From what I can gather from the letters, and the people identified in the other photos, the family lived in upstate New York and were Spiritualists. They speak very nonchalant about receiving messages from the other side. Some of the family names, from what I can tell, were 'Owens', 'Nowland', and 'Carpenter'. I need to do some more work deciphering the content of the letters which are very hard to read.

I have studied spirit photography for several years now and have shown these to some of the top photo collectors, appraisers, museums, and psychics, and they have all said that they're the best they've ever seen.

A well known psychic said she was certain the 'extras' were definitely family members of the sisters and requested copies to hang in her office.

I own several 'standard' spirit photographs on paper, but these tintypes are so beautifully done. Under strong magnification there is no indication of manipulation. Therefore, the real question is, "How were they done when there was no negative involved in the tintype process?"

Also, you have to remember that these were probably taken sometime in the 1860s, using only the processes they had available at the time.

Tintypes were the 'grandfather' of the Polaroid, with just one unique image - no copies - unless you took a photo of the photo. To have done that over and over again would have been very difficult, and the results would not have been very clear.

Even ambrotypes, another process used at the time, which were negatives on glass and then backed with black so they appeared positive, would have been much easier to manipulate.

The only other tintype spirit photographs that I have found have only one or two 'extras' in them, who could have simply stepped out of the image area before the developing of the plate was completed.

On the photo I have, there are over 15 'extras' on just the one with the female sitter, including 4 or 5 in her lap! Many of the 'extras' do not show up very well on the scan, but can be seen clearly under magnification in person. Perhaps they used an elaborate setup with mirrors? Who knows?

They could also be tintype photos taken of paper photographs whose negatives had been manipulated, but they are so clear, and I have yet to see paper spirit photographs, done at the time, done so well.

I should also mention that they are '1/4 Plates' which are larger than the standard, smaller tintypes that were much more popular.

They both measure approx. 3 1/4 x 4 1/4 inches and are housed in a nice thermoplastic case (one of the first forms of plastic) manufactured by Littlefield, Parsons & Co., which was one of the largest photo case manufacturers up until about 1866.

Anyway, I saw that it was mentioned on your website that you never see early spirit tintypes, so I thought I would send you a scan of mine. I must say that you have some really awesome examples posted on your website!

Of course, I can't say exactly how they were created, or if they are the 'real thing', and I'll probably never know for sure, but you have to admit that they are pretty intriguing!

I wish I knew who the photographer was, but there is no indication, which was common with tintypes.

After doing all this research I realized that I have taken a couple spirit photos myself in the past long before I even knew what spirit photography was!

We live in an area that was known to be a 'sacred and neutral zone' along a river where, according to historical records, Native American Indian tribes were not allowed to fight because it was sacred burial ground. We have also found confirmed bison bones on our property, dating back 1,000s of years, probably due to the close proximity of the river.

Best regards,

Debbie Spence