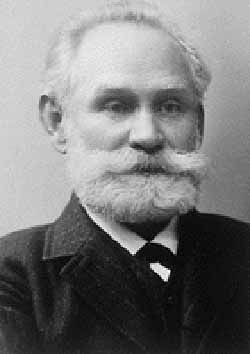

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (September 14, 1849 - February 27, 1936) was a famous Russian physiologist. He was born on September 14, 1849 at Ryazan, where his father, Peter Dmitrievich Pavlov, was a village priest. He was educated first at the church school in Ryazan and then at the theological seminary there.

Inspired by the progressive ideas which D. I. Pisarev, the most eminent of the Russian literary critics of the 1860's and I. M. Sechenov, the father of Russian physiology, were spreading, Pavlov abandoned his religious career and decided to devote his life to science. In 1870 he enrolled in the physics and mathematics faculty to take the course in natural science.

Ivan Pavlov was born in Ryazan, Russia. He began his higher education as a student at the Ryazan Ecclesiastical Seminary, but then dropped out and enrolled in the University of Saint Petersburg to study the natural sciences and became a physiologist. He received his doctorate in 1879.

In the 1890s, Pavlov was investigating the gastric function of dogs by externalizing a salivary gland so he could collect, measure, and analyze the saliva and what response it had to food under different conditions. He noticed that the dogs tended to salivate before food was actually delivered to their mouths, and set out to investigate this "psychic secretion", as he called it.

In 1875 Pavlov completed his course with an outstanding record and received the degree of Candidate of Natural Sciences. However, impelled by his overwhelming interest in physiology, he decided to continue his studies and proceeded to the Academy of Medical Surgery to take the third course there. He completed this in 1879 and was again awarded a gold medal.

After a competitive examination, Pavlov won a fellowship at the Academy, and this together with his position as Director of the Physiological Laboratory at the clinic of the famous Russian clinician, S. P. Botkin, enabled him to continue his research work. In 1883 he presented his doctor's thesis on the subject of - The centrifugal nerves of the heart.

In this work he developed his idea of nervism, using as example the intensifying nerve of the heart which he had discovered, and furthermore laid down the basic principles on the trophic function of the nervous system. In this as well as in other works, resulting mainly from his research in the laboratory at the Botkin clinic, Pavlov showed that there existed a basic pattern in the reflex regulation of the activity of the circulatory organs.

Unlike many pre-revolutionary scientists, Pavlov was highly regarded by the Soviet government, and he was able to continue his research until he reached a considerable age. Moreover, he was praised by Lenin and is a Nobel laureate.

After the murder of Sergei Kirov in 1934, Pavlov wrote several letters to Molotov criticizing the mass persecutions which followed and asking for the reconsideration of cases pertaining to several people he knew personally.

Inspired by the progressive ideas which D. I. Pisarev, the most eminent of the Russian literary critics of the 1860's and I. M. Sechenov, the father of Russian physiology, were spreading, Pavlov abandoned his religious career and decided to devote his life to science. In 1870 he enrolled in the physics and mathematics faculty to take the course in natural science.

Conscious until his very last moment, Pavlov asked one of his students to sit beside his bed and to record the circumstances of his dying. He wanted to create unique evidence of subjective experiences of this terminal phase of life.

Pavlov contributed to many areas of physiology and neurology. Most of his work involved research in temperament, conditioning and involuntary reflex actions. Pavlov performed and directed experiments on digestion, eventually publishing The Work of the Digestive Glands in 1897, after 12 years of research. His experiments earned him the 1904 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.

These experiments included surgically extracting portions of the digestive system from animals, severing nerve bundles to determine the effects, and implanting fistulas between digestive organs and an external pouch to examine the organ's contents. This research served as a base for broad research on the digestive system.

Further work on reflex actions involved involuntary reactions to stress and pain. Pavlov extended the definitions of the four temperament types under study at the time: phlegmatic, choleric, sanguine, and melancholic, updating the names to "the strong and impetuous type, the strong equilibrated and quiet type, the strong equilibrated and lively type, and the weak type." Pavlov and his researchers observed and began the study of transmarginal inhibition (TMI), the body's natural response of shutting down when exposed to overwhelming stress or pain by electric shock.

This research showed how all temperament types responded to the stimuli the same way, but different temperaments move through the responses at different times. He commented "that the most basic inherited difference. .. was how soon they reached this shutdown point and that the quick-to-shut-down have a fundamentally different type of nervous system."

Carl Jung continued Pavlov's work on TMI and correlated the observed shutdown types in animals with his own introverted and extroverted temperament types in humans. Introverted persons, he believed, were more sensitive to stimuli and reached a TMI state earlier than their extroverted counterparts. This continuing research branch is gaining the name highly sensitive persons.

William Sargant and others continued the behavioral research in mental conditioning to achieve memory implantation and brainwashing (any effort aimed at instilling certain attitudes and beliefs in a person).

The concept for which Pavlov is famous is the "conditioned reflex" he developed jointly with his assistant Ivan Filippovitch Tolochinov in 1901. Tolochinov, whose own term for the phenomenon had been "reflex at a distance", communicated the results at the Congress of Natural Sciences in Helsinki in 1903.

As Pavlov's work became known in the West, particularly through the writings of John B. Watson, the idea of "conditioning" as an automatic form of learning became a key concept in the developing specialism of comparative psychology, and the general approach to psychology that underlay it, behaviorism. The British philosopher Bertrand Russell was an enthusiastic advocate of the importance of Pavlov's work for philosophy of mind.

Pavlov's research on conditional reflexes greatly influenced not only science, but also popular culture. The phrase "Pavlov's dog" is often used to describe someone who merely reacts to a situation rather than using critical thinking. Pavlovian conditioning was a major theme in Aldous Huxley's dystopian novel, Brave New World, and also to a large degree in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow.

It is popularly believed that Pavlov always signaled the occurrence of food by ringing a bell. However, his writings record the use of a wide variety of stimuli, including electric shocks, whistles, metronomes, tuning forks, and a range of visual stimuli, in addition to ringing a bell. Cataniacast doubt on whether Pavlov ever actually used a bell in his famous experiments. Littman tentatively attributed the popular imagery to PavlovÕs contemporaries Vladimir Mikhailovich Bekhterev and John B. Watson, until Thomas found several references that unambiguously stated Pavlov did, indeed, use a bell.