Nubia Region Today

Nubia Region Today

Nubia was also called - Upper & Lower Nubia, Kush, Land of Kush, Te-Nehesy, Nubadae, Napata, or the Kingdom of Meroe.

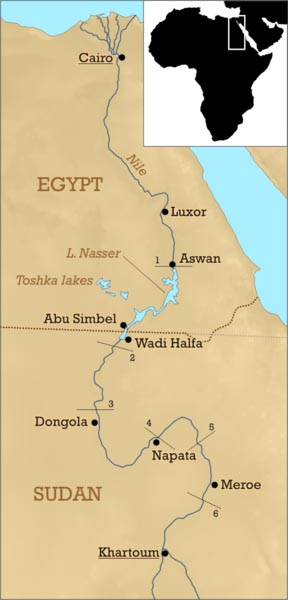

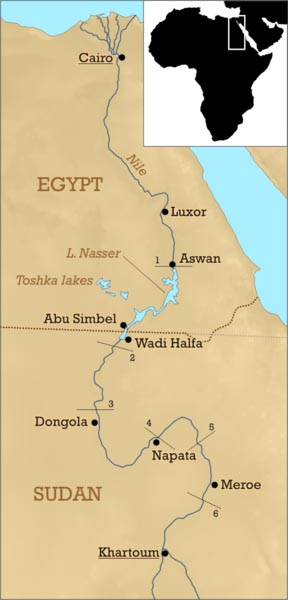

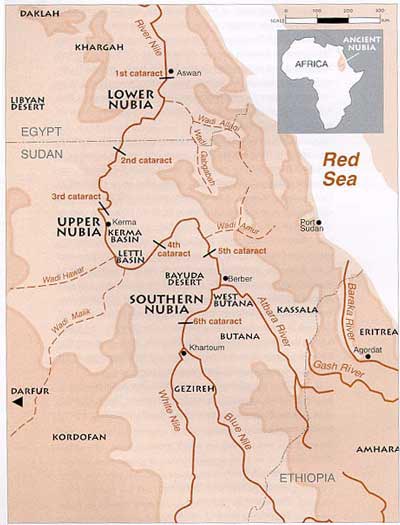

The region referred to as Lower Egypt is the northernmost portion. Upper Nubia extends south into Sudan and can be subdivided into several separate areas such as Batn El Hajar or "Belly of Rocks", the sands of the Abri-Delgo Reach, or the flat plains of the Dongola Reach. Nubia, the hottest and most arid region of the world, has caused many civilizations to be totally dependent on the Nile for existence.

Historically Nubia has been a nucleus of diverse cultures. It has been the only occupied strip of land connecting the Mediterranean world with "tropical" Africa. Thus, this put the people in close and constant contact with its neighbors for long periods of history and Nubia was an important trade route between sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the world. Its rich material culture and tradition of languages are seen in archaeological records.

The most prosperous period of Nubian civilization was that of the kingdom of Kush, which endured from about 800 BC to about 320 AD. During this time, the Nubians of Kush would at one point, assume rule over all of Nubia as well as Upper and Lower Egypt.

The regions of Nubia, Sudan and Egypt are considered by some to be the cradle of civilization. Today the term Nubian has become inclusive of Africans, African Arabs, African Americans and people of color in general.

Nubia is divided into three regions: Lower Nubia, Upper Nubia, and Southern Nubia. Lower Nubia was in modern southern Egypt, which lies between the first and second cataract. Upper Nubia and Southern Nubia were in modern-day northern Sudan, between the second cataract and sixth cataracts of the Nile river. Lower Nubia and Upper Nubia are so called because the Nile flows north, so Upper Nubia was further upstream and of higher elevation, even though it lies geographically south of Lower Nubia.

Marks on 4,000-year-old skeletons reveal that Bronze Age women in Nubia were carrying goods and young children on their heads using tumplines, a type of head strap that can hold a basket Live Science - April 8, 2025

Researchers made the finding in Sudan after analyzing the remains of 30 people (14 females and 16 males) buried in a Nubian Bronze Age cemetery. One, an elite woman who was around 50 years old when she died, had the clearest marks indicative of head straps. This is the "first clear evidence that women were using head straps - tumplines - to carry loads as early as the Bronze Age.

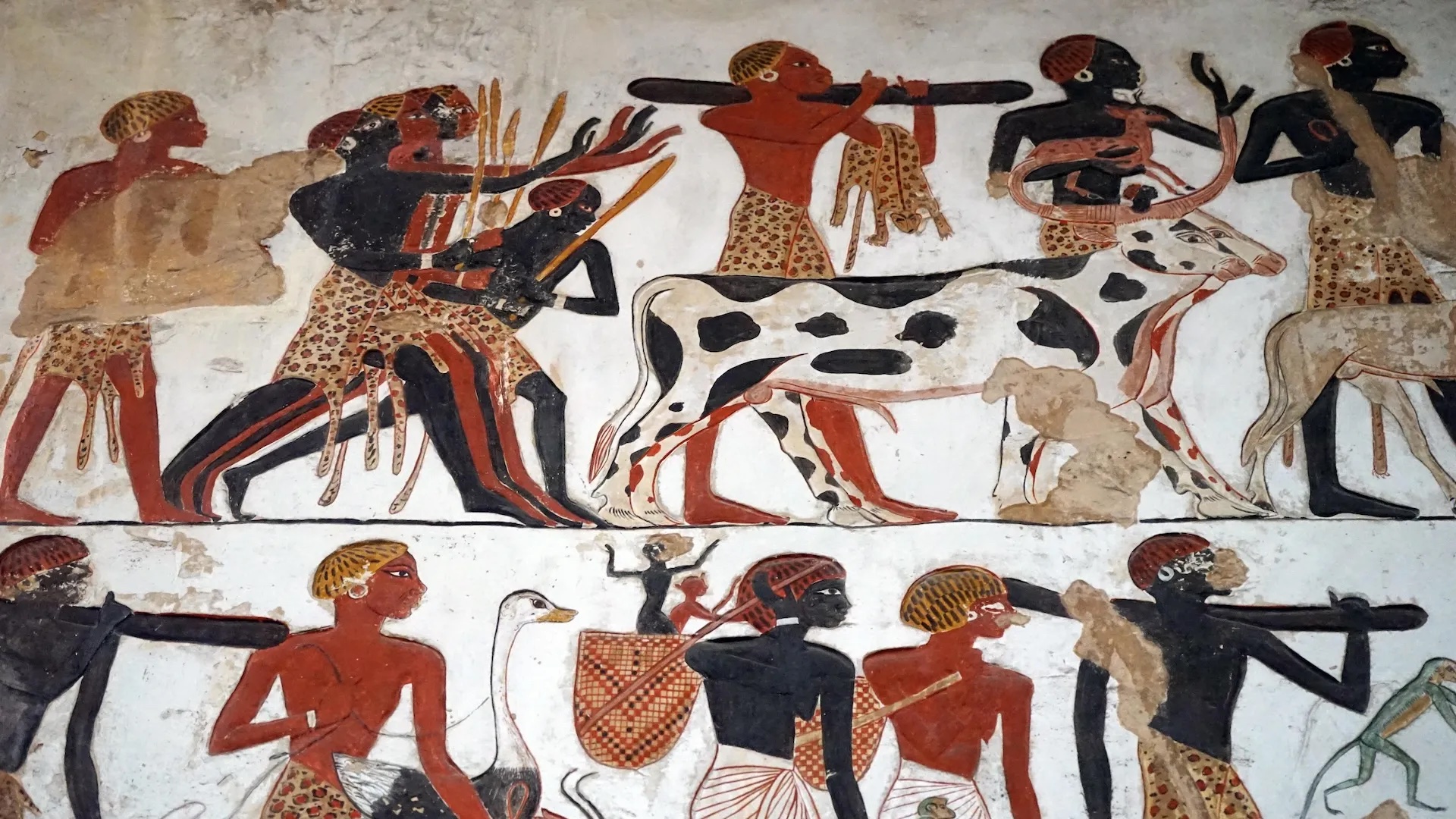

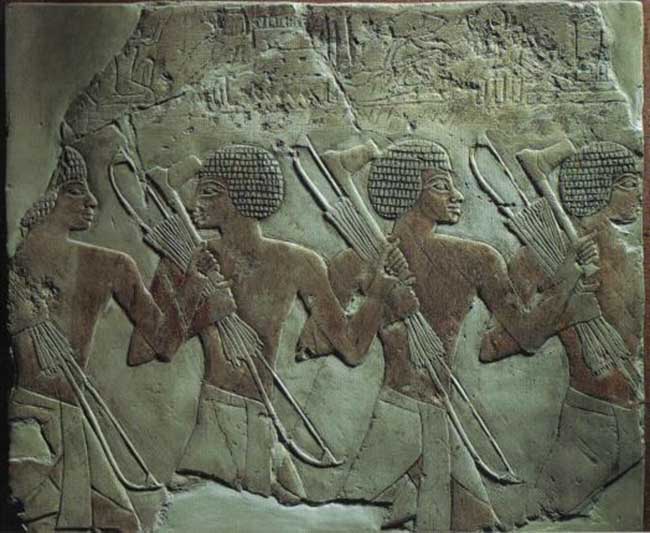

Early settlements sprouted in both Upper and Lower Nubia: The Restricted flood plains of Lower Nubia. Egyptians referred to Nubia as "Ta-Seti." The Nubians were known to be expert archers and thus their land earned the appellation, "Ta-Seti", or land of the bow. Modern scholars typically refer to the people from this area as the 'A-group' culture. Fertile farmland just south of the third cataract is known as the “Pre-Kerma” culture in Upper Nubia, as they are the ancestors civilization originated in 5000 BC in Upper Nubia..

The Neolithic people in the Nile valley likely came from Sudan, as well as the Sahara, and there was shared culture with the two areas and with that of Egypt during this time period.

By the 5th millennium BC, the people who inhabited what is now called Nubia participated in the Neolithic revolution. Saharan rock reliefs depict scenes that have been thought to be suggestive of a cattle cult, typical of those seen throughout parts of Eastern Africa and the Nile Valley even to this day.

Megaliths discovered at Nabta Playa are early examples of what seems to be one of the world's first astronomical devices, predating Stonehenge by almost 2000 years. This complexity as observed at Nabta Playa, and as expressed by different levels of authority within the society there, likely formed the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.

Around 3800 BC, the second "Nubian" culture, termed the A-Group, arose. It was a contemporary of, and ethnically and culturally very similar to, the polities in predynastic Naqada of Upper Egypt.

Around 3300 BC, there is evidence of a unified kingdom, as shown by the finds at Qustul, that maintained substantial interactions (both cultural and genetic) with the culture of Naqadan Upper Egypt. The Nubian culture may have even contributed to the unification of the Nile valley. Also, the Nubians very likely contributed some pharaonic iconography, such as the white crown and serekh, to the Northern Egyptian kings.

Around the turn of the protodynastic period, Naqada, in its bid to conquer and unify the whole Nile valley, seems to have conquered Ta-Seti (the kingdom where Qustul was located) and harmonized it with the Egyptian state. Thus, Nubia became the first nome of Upper Egypt. At the time of the first dynasty, the A-Group area seems to have been entirely depopulated most likely due to immigration to areas west and south.

This culture began to decline in the early 28th century BC. The succeeding culture is known as B-Group. Previously, the B-Group people were thought to have invaded from elsewhere. Today most historians believe that B-Group was merely A-Group but far poorer. The causes of this are uncertain, but it was perhaps caused by Egyptian invasions and pillaging that began at this time. Nubia is believed to have served as a trade corridor between Egypt and tropical Africa long before 3100 BC. Egyptian craftsmen of the period used ivory and ebony wood from tropical Africa which came through Nubia.

In 2300 BC, Nubia was first mentioned in Old Kingdom Egyptian accounts of trade missions. From Aswan, right above the First Cataract, southern limit of Egyptian control at the time, Egyptians imported gold, incense, ebony, ivory, and exotic animals from tropical Africa through Nubia. As trade between Egypt and Nubia increased so did wealth and stability.

By the Egyptian 6th dynasty, Nubia was divided into a series of small kingdoms. There is debate over whether these C-Group peoples, who flourished from c. 2240 BC to c. 2150 BC, were another internal evolution or invaders. There are definite similarities between the pottery of A-Group and C-Group, so it may be a return of the ousted Group-As, or an internal revival of lost arts. At this time, the Sahara Desert was becoming too arid to support human beings, and it is possible that there was a sudden influx of Saharan nomads. C-Group pottery is characterized by all-over incised geometric lines with white infill and impressed imitations of basketry.

During the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (c. 2040-1640 BC), Egypt began expanding into Nubia to gain more control over the trade routes in Northern Nubia and direct access to trade with Southern Nubia. They erected a chain of forts down the Nile below the Second Cataract. These garrisons seemed to have peaceful relations with the local Nubian people but little interaction during the period. A contemporaneous but distinct culture from the C-Group was the Pan Grave culture, so called because of their shallow graves. The Pan Graves are associated with the East bank of the Nile, but the Pan Graves and C-Group definitely interacted. Their pottery is characterized by incised lines of a more limited character than those of the C-Group, generally having interspersed undecorated spaces within the geometric schemes.

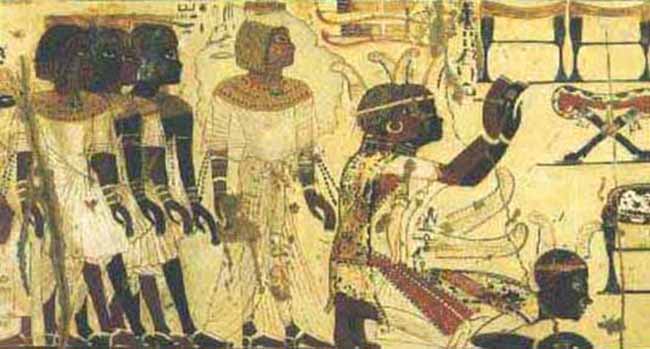

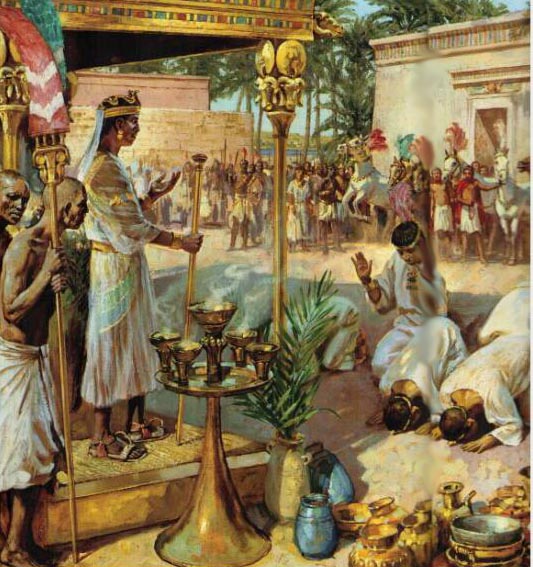

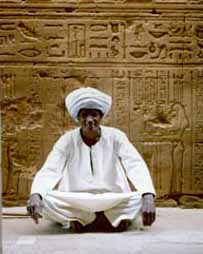

Medja Temple Relief

The history of the Nubians is closely linked with that of ancient Egypt. Ancient Egypt conquered Nubian territory incorporating them into its provinces. The Nubians in turn were to conquer Egypt in its 25th Dynasty. However, relations between the two peoples also show peaceful cultural interchange and cooperation, including mixed marriages.

The Medjay represents the name Ancient Egyptians gave to a region in northern Sudan where an ancient people of Nubia inhabited. They became part of the Ancient Egyptian military as scouts and minor workers. During the Middle Kingdom "Medjay" no longer referred to the district of Medja, but to a tribe or clan of people. It is not known what happened to the district, but, after the First Intermediate Period, it and other districts in Nubia were no longer mentioned in the written record.

Written accounts detail the Medjay as nomadic desert people. Over time they were incorporated into the Egyptian army where that served as garrison troops in Egyptian fortifications in Nubia and patrolled the deserts. This was done in the hopes of preventing their fellow Medjay tribespeople from further attacking Egyptian assets in the region. They were later used during Kamose’s campaign against the Hyksos and became instrumental in making the Egyptian state into a military power.

By the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom the Medjay were an elite paramilitary police force. No longer did the term refer to an ethnic group and over time the new meaning became synonymous with the policing occupation in general. Being an elite police force, the Medjay were often used to protect valuable areas, especially royal and religious complexes. Though they are most notable for their protection of the royal palaces and tombs in Thebes and the surrounding areas, the Medjay were known to have been used throughout Upper and Lower Egypt.

Various pharaohs of Nubian origin are held by some Egyptologists to have played an important part towards the area in different eras of Egyptian history, particularly the 12th Dynasty. These rulers handled matters in typical Egyptian fashion, reflecting the close cultural influences between the two regions.

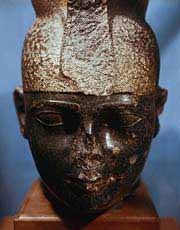

The XII Dynasty (1991-1786 B.C.E.) originated from the Aswan region. As expected, strong Nubian features and dark coloring are seen in their sculpture and relief work. This dynasty ranks as among the greatest, whose fame far outlived its actual tenure on the throne. Especially interesting, it was a member of this dynasty that decreed that no Nehsy (riverine Nubian of the principality of Kush), except such as came for trade or diplomatic reasons, should pass by the Egyptian fortress and cops at the southern end of the Second Nile Cataract.

In the New Kingdom, Nubians and Egyptians were often closely related that some scholars consider them virtually indistinguishable, as the two cultures combined. The result has been described as a wholesale Nubian assimilation into Egyptian society. This assimilation was so complete that it masked all Nubian ethnic identities insofar as archaeological remains are concerned beneath the impenetrable veneer of Egypt's material culture.

In the Kushite Period, when Nubians ruled as Pharaohs in their own right, the material culture of Dynasty XXV (about 750-655 B.C.E.) was decidedly Egyptian in character. Nubia's entire landscape up to the region of the Third Cataract was dotted with temples indistinguishable in style and decoration from contemporary temples erected in Egypt. The same observation obtains for the smaller number of typically Egyptian tombs in which these elite Nubian princes were interred.

From the pre-Kerma culture, the first kingdom to unify much of the region arose. The Kingdom of Kerma, named for its presumed capital at Kerma, was one of the earliest urban centers in the Nile region.

By 1750 BC, the kings of Kerma were powerful enough to organize the labor for monumental walls and structures of mud brick. They also had rich tombs with possessions for the afterlife and large human sacrifices. George Reisner excavated sites at Kerma and found large tombs and a palace-like structures. The structures, named (Deffufa), alluded to the early stability in the region.

At one point, Kerma came very close to conquering Egypt. Egypt suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Kushites. According to Davies, head of the joint British Museum and Egyptian archaeological team, the attack was so devastating that if the Kerma forces chose to stay and occupy Egypt, they might have eliminated it for good and brought the great nation to extinction. When Egyptian power revived under the New Kingdom (c. 1532-1070 BC) they began to expand further southwards.

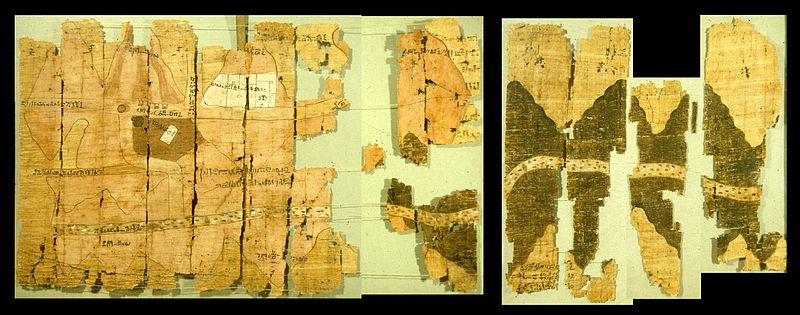

The Egyptians destroyed Kerma's kingdom and capitol and expanded the Egyptian empire to the Fourth Cataract. By the end of the reign of Thutmose I (1520 BC), all of northern Nubia had been annexed. The Egyptians built a new administrative center at Napata, and used the area to produce gold. The Nubian gold production made Egypt a prime source of the precious metal in the Middle East. The primitive working conditions for the slaves are recorded by Diodorus Siculus who saw some of the mines at a later time. One of the oldest maps known is of a gold mine in Nubia, the Turin Papyrus Map dating to about 1160 BC.

The Nubian Pharaohs: Black Kings of the Nile

In 2003, a Swiss archaeological team working in northern Sudan uncovered one of the most remarkable Egyptological finds in recent years. At the site known as Kerma, near the third cataract of the Nile, archaeologist Charles Bonnet and his team discovered a ditch within a temple from the ancient city of Pnoubs, which contained seven monumental black granite statues.

Rare Nubian King Statues Uncovered in Sudan - National Geographic - February 27, 2003

The finding is the strongest evidence yet that the art of making antibiotics, which officially dates to the discovery of penicillin in 1928, was common practice nearly 2,000 years ago. The statues were found in a pit in Kerma, south of the Third Cataract of the Nile. he seven statues, which stood between 1.3 to 2.7 meters (4 to 10 feet) tall, were inscribed with the names of five of Nubia's kings: Taharqa, Tanoutamon, Senkamanisken, Anlamani, and Aspelta. Taharqa and Tanoutamon ruled Egypt as well as Nubia. Sometimes known as the "Black Pharaohs," Nubian kings ruled Egypt from roughly 760 B.C. to 660 B.C.

Black pharaoh trove uncovered in north Sudan BBC - January 20, 2003

A team of French and Swiss archaeologists working in the Nile Valley have uncovered ancient statues described as sculptural masterpieces in northern Sudan. The archaeologists from the University of Geneva discovered a pit full of large monuments and finely carved statues of the Nubian kings known as the black pharaohs. The Swiss head of the archaeological expedition told the BBC that the find was of worldwide importance. The black pharaohs, as they were known, ruled over a mighty empire stretching along the Nile Valley 2,500 years ago.

The Kingdom of Kush or Kush was an ancient African kingdom situated on the confluences of the Blue Nile, White Nile and River Atbara in what is now the Republic of Sudan.

Established after the Bronze Age collapse and the disintegration of the New Kingdom of Egypt, it was centered at Napata in its early phase. After king Kashta ("the Kushite") invaded Egypt in the 8th century BC, the Kushite kings ruled as Pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt for a century, until they were expelled by Psamtik I in 656 BC.

When the Egyptians pulled out of the Napata region, they left a lasting legacy that was merged with indigenous customs forming the kingdom of Kush. Archaeologists have found several burials in the area which seem to belong to local leaders. The Kushites were buried there soon after the Egyptians decolonized the Nubian frontier. Kush adopted many Egyptian practices, such as their religion. The Kingdom of Kush survived longer than that of Egypt, invaded Egypt (under the leadership of king Piye), and controlled Egypt during the 8th century, Kushite dynasty.

The Kushites held sway over their northern neighbors for nearly 100 years, until they were eventually repelled by the invading Assyrians. The Assyrians forced them to move farther south, where they eventually established their capital at Meroe. Of the Nubian kings of this era, Taharqa is perhaps the best known. Taharqa, a son and the third successor of King Piye, was crowned king in Memphis in c.690. Taharqa ruled over both Nubia and Egypt, restored Egyptian temples at Karnak, and built new temples and pyramids in Nubia, before being driven from Egypt by the Assyrians.

During Classical Antiquity, the Kushite imperial capital was at Meroe. In early Greek geography, the Meroitic kingdom was known as Ethiopia. Anatomically modern humans emerged from modern-day Ethiopia and set out for the Near East and elsewhere in the Middle Paleolithic period. Read more ...

The Kushite kingdom with its capital at Meroe persisted until the 4th century AD, when it weakened and disintegrated due to internal rebellion. The Kushite capital was subsequently captured by the Beja Dynasty, who tried to revive the empire. The Kushite capital was eventually captured and destroyed by the kingdom of Axum. After the collapse of the Kushite empire several states emerged in its former territories, among them Nubia.

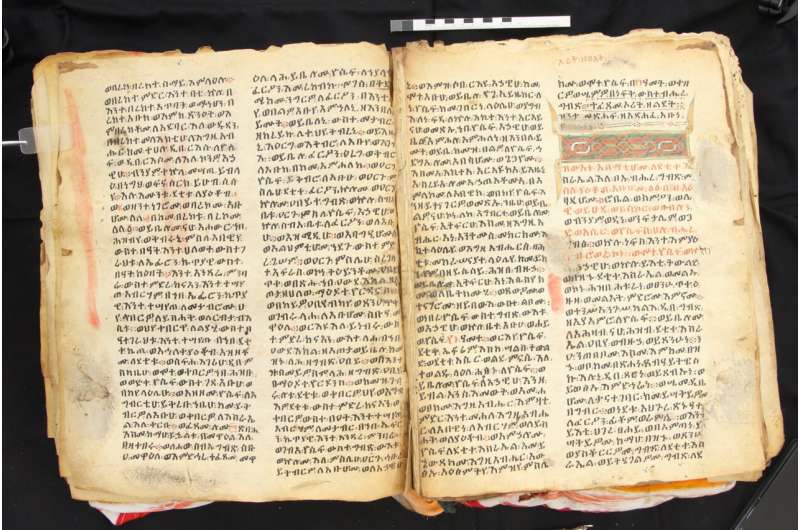

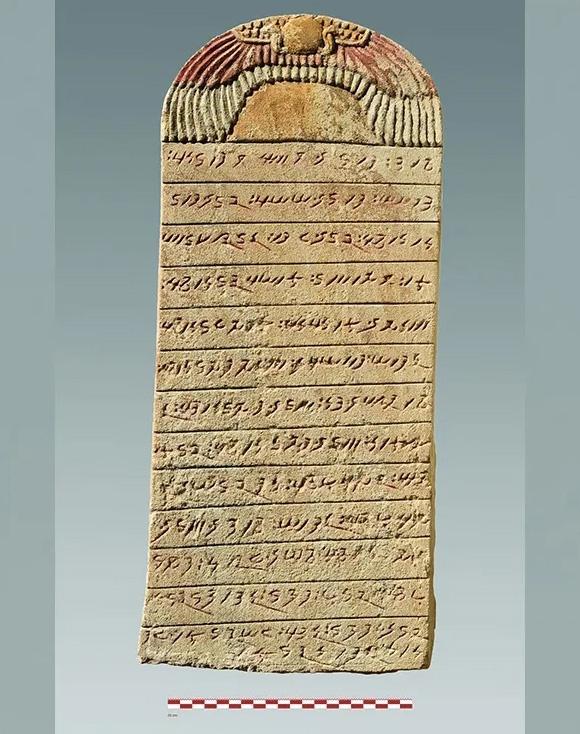

Meroe (800 BC - c. AD 350) in southern Nubia lay on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, ca. 200 km north-east of Khartoum. The people there preserved many ancient Egyptian customs but were unique in many respects. They developed their own form of writing, first utilizing Egyptian hieroglyphs, and later using an alphabetic script with 23 signs.

Many pyramids were built in Meroe during this period and the kingdom consisted of an impressive standing military force. Strabo also describes a clash with the Romans in which the Romans were defeated by Nubian archers under the leadership of a "one-eyed" (blind in one eye) queen. During this time, the different parts of the region divided into smaller groups with individual leaders, or generals, each commanding small armies of mercenaries. They fought for control of what is now Nubia and its surrounding territories, leaving the entire region weak and vulnerable to attack. Meroe would eventually meet defeat by a new rising kingdom to their south, Aksum, under King Ezana.

The classification of the Meroitic language is uncertain, it was long assumed to have been of the Afro-Asiatic group, but is now considered to have likely been an Eastern Sudanic language.

At some point during the 4th century, the region was conquered by the Noba people, from which the name Nubia may derive (another possibility is that it comes from Nub, the Egyptian word for gold). From then on, the Romans referred to the area as the Nobatae.

Meroe was the base of a flourishing kingdom whose wealth was due to a strong iron industry, and international trade involving India and China. So much metalworking went on in Meroe, through the working of bloomeries and possibly blast furnaces, that it has even been called "the Birmingham of Africa" because of its vast production and trade of iron to the rest of Africa, and other international trade partners.

At the time, iron was one of the most important metals worldwide, and Meroitic metalworkers were among the best in the world. Meroe also exported textiles and jewelry. Their textiles were based on cotton and working on this product reached its highest achievement in Nubia around 400 BC. Furthermore, Nubia was very rich in gold. It is possible that the Egyptian word for gold, nub, was the source of name of Nubia. Trade in "exotic" animals from farther south in Africa was another feature of their economy.

The Egyptian import, the water-moving wheel, the sakia, was used to move water, in conjunction with irrigation, to increase crop production.

At the peak, the rulers of Meroe controlled the Nile valley north to south over a straight line distance of more than 1,000 km (620 mi).

The King of Meroe was an autocrat ruler who shared his authority only with the Queen Mother, or Candace. However, the role of the Queen Mother remains obscure. The administration consisted of treasurers, seal bearers, heads of archives, and chief scribes, among others.

By the 3rd century BC a new indigenous alphabet, the Meroitic, consisting of twenty-three letters, replaced Egyptian script. The Meroitic script is an alphabetic script originally derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs, used to write the Meroitic language of the Kingdom of Meroe/Kush. It was developed in the Napatan Period (about 700-300 BC), and first appears in the 2nd century BC. For a time, it was also possibly used to write the Nubian language of the successor Nubian kingdoms.

Although the people of Meroe also had southern deities such as Apedemak, the lion-son of Sekhmet (or Bast, depending upon the region), they also continued worshipping Egyptian deities they had brought with them, such as Amun, Tefnut, Horus, Isis, Thoth, and Satis, though to a lesser extent.

The site of Meroe was brought to the knowledge of Europeans in 1821 by the French mineralogist Frederic Cailliaud (1787-1869), who published an illustrated in-folio describing the ruins. Some treasure-hunting excavations were executed on a small scale in 1834 by Giuseppe Ferlini, who discovered (or professed to discover) various antiquities, chiefly in the form of jewelry, now in the museums of Berlin and Munich.

The ruins were examined more carefully in 1844 by Karl Richard Lepsius, who took many plans, sketches, and copies, besides actual antiquities, to Berlin.

Further excavations were carried on by E. A. Wallis Budge in the years 1902 and 1905, the results of which are recorded in his work, The Egyptian Sudan: its History and Monuments (London, 1907). Troops furnished by Sir Reginald Wingate, governor of Sudan, made paths to and between the pyramids, and sank shafts.

It was found that the pyramids were commonly built over sepulchral chambers, containing the remains of bodies, either burned, or buried without being mummified. The most interesting objects found were the reliefs on the chapel walls, already described by Lepsius, which present the names and representations of their queens, Candaces, or the Nubian Kentakes, some kings, and some chapters of the Book of the Dead; some stelae with inscriptions in the Meroitic language; and some vessels of metal and earthenware. The best of the reliefs were taken down stone by stone in 1905, and set up partly in the British Museum, and partly in the museum at Khartoum.

In 1910, in consequence of a report by Archibald Sayce, excavations were commenced in the mounds of the town, and in the necropolis, by John Garstang, on behalf of the University of Liverpool. Garstang discovered the ruins of a palace and several temples built by the Meroite rulers.

Ancient Carving Shows Stylishly Plump African Princess Live Science - January 3, 2012

A 2,000-year-old relief carved with an image of what appears to be a, stylishly overweight, princess has been discovered in an "extremely fragile" palace in the ancient city of Meroe, in Sudan, archaeologists say. At the time the relief was made, Meroe was the center of a kingdom named Kush, its borders stretching as far north as the southern edge of Egypt. It wasn't unusual for queens (sometimes referred to as "Candaces") to rule, facing down the armies of an expanding Rome. The sandstone relief shows a woman smiling, her hair carefully dressed and an earring on her left ear. She appears to have a second chin and a bit of fat on her neck, something considered stylish, at the time, among royal women from Kush.

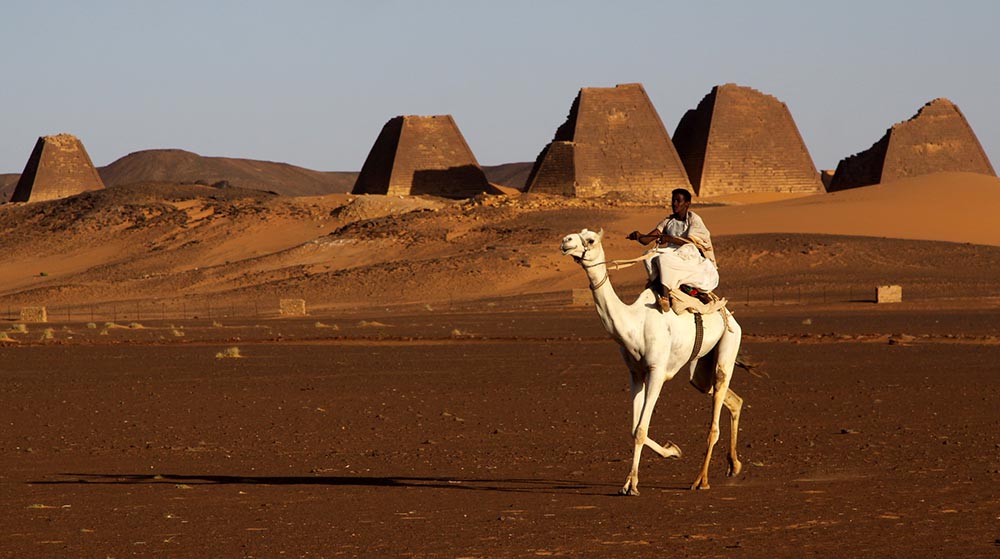

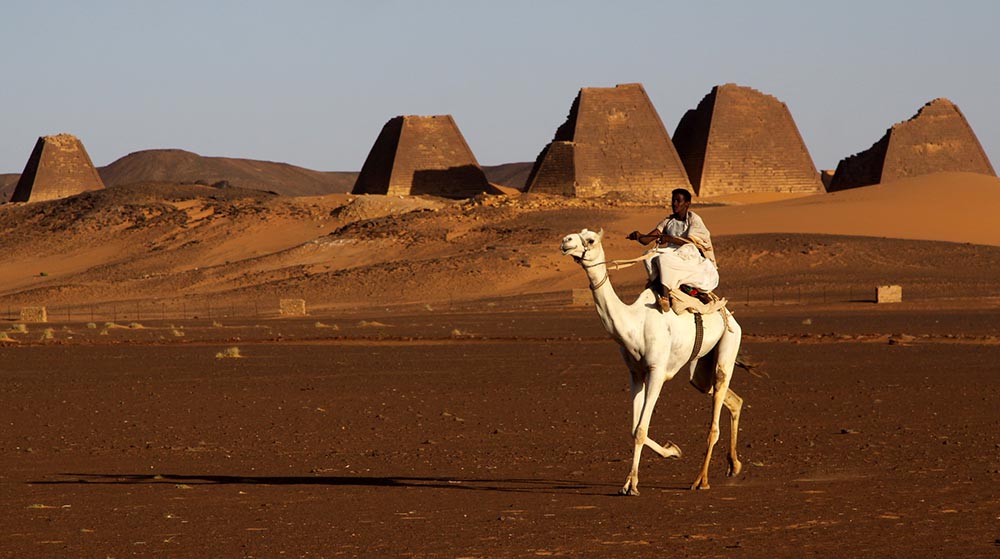

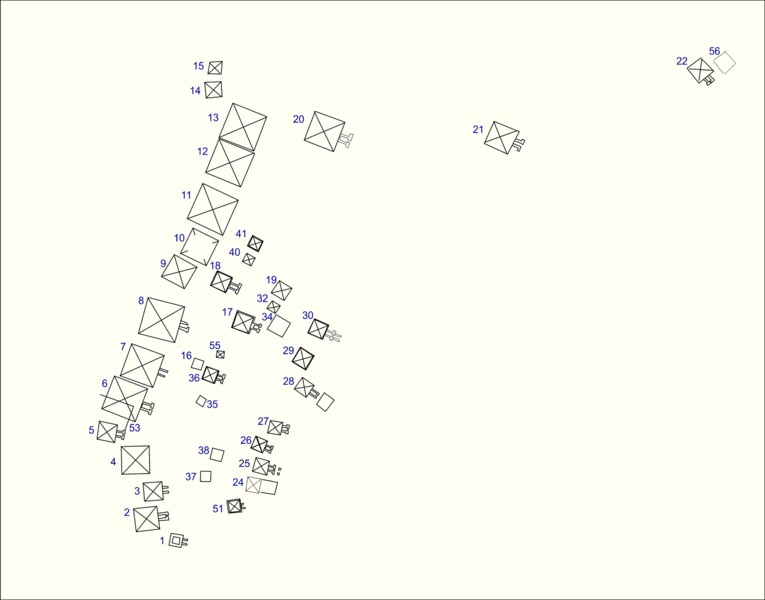

More than fifty ancient pyramids and royal tombs rise out of the desert sands at Meroe.

They are Sudan's best-preserved pyramids.

Images of early Gods are not unlike those found on hieroglyphs of Egyptian Gods - with heads of animals and birds.

Pyramids from the Northern Cemetery at Meroe, 3rd c. B.C. to 4th c. A.D. By the 4th c. B.C., the Kushite kings had moved south to the Sudanese savannah and built a capitol at Meroe. Here southern cultural traditions slowly prevailed over the cultural heritage of Egypt.

Like the Egyptians, the Kushites believed in a life after death. This was thought to because a continuation of life on earth. For them, the afterlife resembled this one, and they built huge graves as an enduring home for the dead. The unique social position of the pharaoh, as god on earth, was reflected in his tomb.

The king was the son of Amun-Pa the sun god and as such embodied the sun on earth. Like the sun, his life followed a cyclical plan. His youth resembled the sun rising, his maturity was like the sun at noon and his old age was comparable with the setting sun. When the king died the sun disappeared below the horizon and darkness fell.

Mythology recounted that the dying or setting sun travelled through the underworld in its journey towards the east where it was to be reborn at the dawn of the day. From time immemorial the pyramid represented the rising sun and the resurrection, and people believed that a tomb in this shape would offer the dead king the chance of rising out of death. The pyramid was seen as a ladder up to heaven enabling the dead king's soul to travel and join the gods in the heavens. At night time the king, assuming the shape of Osiris, god of the afterlife and resurrection, descended in the barque of the sun god Ra and, having become one with this god, sailed through the bouts of darkness.

Building pyramids ceased towards the end of the Middle Kingdom period. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom constructed their graves in caves with underground rooms and passages symbolizing the nightly sojourn of the sun god. The black pharaohs of the Kushite Dynasty and their descendants readopted the old pyramids for their tombs. The number of pyramids in Nubia, where a total of 223 bas been round, fat exceeds that of Egypt.

The pyramids of Nubia have three important sections. These are: 1) an underground burial place symbolizing the underworld, where the mummy lies; 2) a massive steep pyramid above, symbolizing the ladder up to heaven; 3) a small chapel on the eastern side where sacrifices could bc placed, intended to sustain the dead king on his travels. Perhaps the doors to this chapel would be opened by a priest at sunrise so that the light could shine in on the stela that was placed against the rear wall. The chapel thus also functioned as a place of prayer connected with the cult of the dead.

The underground graves of the Nubian pyramids were richly decorated. The mummified kings and queens were laid upon beds in accordance with the ancient tradition of Kerma. So that the dead monarch would not have to work in the afterlife, their tombs were filled with shabtis, small statues of people which in a magical manner would come to life when summoned by the gods to perform tasks.

16 Pyramids Discovered in Ancient Sudan Cemetery Live Science - September 16, 2015

The remains of 16 pyramids with tombs underneath have been discovered in a cemetery near the ancient town of Gematon in Sudan. They date back around 2,000 years, to a time when a kingdom called "Kush" flourished in Sudan. Pyramid building was popular among the Kushites. They built them until their kingdom collapsed in the fourth century AD. Derek Welsby, a curator at the British Museum in London, and his team have been excavating at Gematon since 1998, uncovering the 16 pyramids, among many other finds, in that time. The largest pyramid found at Gematon was 10.6 meters (about 35 feet) long on each side and would have risen around 13 m (43 feet) off the ground.

Wealthy and powerful individuals built some of the pyramids, while people of more modest means built the others. They're not just the upper-elite burials. In fact, not all the tombs in the cemetery have pyramids: Some are buried beneath simple rectangular structures called "mastaba," whereas others are topped with piles of rocks called "tumuli." Meanwhile, other tombs have no surviving burial markers at all.

Wealthy and powerful individuals built some of the pyramids, while people of more modest means built the others. They're not just the upper-elite burials. In fact, not all the tombs in the cemetery have pyramids: Some are buried beneath simple rectangular structures called "mastaba," whereas others are topped with piles of rocks called "tumuli." Meanwhile, other tombs have no surviving burial markers at all.

The Kushite kingdom controlled a vast amount of territory in Sudan between 800 B.C. and the fourth century A.D. There are a number of reasons why the Kushite kingdom collapsed. One important reason is that the Kushite rulers lost several sources of revenue. A number of trade routes that had kept the Kushite rulers wealthy bypassed the Nile Valley, and instead went through areas that were not part of Kush. As a result, Kush lost out on the economic benefits, and the Kush rulers lost out on revenue opportunities. Additionally, as the economy of the Roman Empire deteriorated, trade between the Kushites and Romans declined, further draining the Kushite rulers of income. As the Kushite leaders lost wealth, their ability to rule faded. Gematon was abandoned, and pyramid building throughout Sudan ceased. Wind-blown sands, which had always been a problem for those living at Gematon, covered both the town and its nearby pyramids.

Ruins of the Merotic temple at Musawwarat es-Sufra.

A number of major sites dot the Sudanese map of great Kushite and Meroitic archaeological sites. Following the tarmac road that connects Khartoum to Atbara, one drives for no more than two or three hours before reaching Musawwarat Es Sufra. Musawwarat is an Arabic word that translates to depictions. Es Sufra begs two theories behind the naming. One school of thought believes it is an adaptation of Es Safra The Yellow as most of the remaining ruins are actually yellowish in color.

Alternatively, Es Sufra means The Dinning Table, an association to a table-like mountain located at a short distance. Regardless of the naming and its origin, Musawwarat Es Sufra is the largest temple complex dating back to the Meroitic Period. It consists of two main parts -- the Great Enclosure and the Lion Temple. The Great Enclosure is a vast structure consisting of low walls, a colonnade, two reservoirs and two inclined long ramps.

The purpose this enclosure had served is vague, perhaps a pilgrammage center or a royal palace. One proposes that it had been an elephant training camp. In addition to the two ramps that might have been used for the big animals to go up and down, and also in addition to the elephants' statues that can be found in the vicinity, the greatest collection of elephant carvings I have seen in Sudan is in the Great Complex.

On the other hand, the nearby Lion Temple might have been a place of pilgrimage and pilgrims used to be housed in the Great Complex. This is backed by ancient graffiti and carvings depicting Apedemak. A human body with a lion head, Apedemak was the most widely worshipped local deity throughout the entire Kushite Kingdom. Built by King Arnekhamani around 230 BC, the Lion Temple in Musawwarat Es Sufra is one of the most well preserved sites in Sudan. It was elegantly restored by the Humboldt University in Berlin in the 1960s.

Next to the Lion Temple is an unidentified edifice known as the Kiosk, reflecting an amalgam of different cultures. Kushite, Egyptian, along with Roman, have all left a distinctive mark on its architecture. A stroll away from the Lion Temple is another temple built by King Natakamani, this time dedicated to the Egyptian god Amun. As you might have noticed, most of the Kushite kings' names end with the syllable "amani" while the majority of the queens' start with it. "Amani" is a linguistic derivative from Amun, an indication of how widely the Egyptian deity was respected and worshipped in Kush. Built in the last century AD, the Temple of Amun in Naqa follows the same overall structure of other Amun temples, mainly Jabal Barrkal in Sudan and Karnak in Egypt. The carving of the rams in Sudan has a distinct style when compared to those in Karnak.

They loom from a distance, a congregation of pyramids on both sides of the road, a living history that bears witness to the greatness of the Kushite Civilization; these are the Pyramids of Meroe, made up of three groups -- western, southern and northern. The northern is the best preserved, containing more than 30 pyramids. Though inspirationally Egyptian, there are differences. The Pyramids of Meroe are much smaller in size when compared to those in Giza, with the largest being just under 30 metres in height.

Another difference is the location of the tomb. Contrary to the Egyptian style, the Kushites had their deceased buried in tombs underneath the pyramid, not inside it, with the majority of the pyramids having a funerary chamber in front and facing eastward. After the first few minutes you spend in Meroe you notice that most of the pyramids have a chopped-off top, and that has a story. An Italian treasure hunter by the name of Guiseppe Ferlini was convinced there was gold. In 1834 and after concurrence of the ruling Turco-Egyptians, he started the shameful destruction. To the surprise of everybody, including historians, he hit the jackpot, striking gold in his first attempt at Pyramid Six, that of Queen Amanishakheto. That encouraged him to go further with the mayhem. But it yielded no gold; just smashed pyramids and an ugly mark in the book of history.

Another very important site is that of Jabal Barkkal, where Egyptian Pharaoh Tuthmoses III built the first Temple of Amun in Sudan around the 15th century BC. It was later expanded by the prominent Ramses II, turning the site into a major centre for the cult of Amun. Right next to it is another monument, the Temple of Mut. Built to the order of Taharqa, and dedicated to Mut, the Egyptian Sky goddess and bride of Amun, the temple is engraved into Jabal Barkkal itself. Very interesting scenery is that of the two temples from the top of the mountain. Make sure to do the easy climb in the morning so you have the light at the right angle for your souvenir photograph. Also on the western side of Jabal Barkkal lies a small royal cemetery of 20 pyramids at the mountain's foot. For a period of time, Kushites would bury their royals at Napata before shifting to Meroe.

Not far from Jabbal Barkkal there are two more sites worth visiting. The Pyramids of Nuri where Taharqa is buried in the largest of its pyramids. When it was excavated in 1917 archaeologist George Reisner uncovered a cache of over 1,000 small statues of the late king. Finally a visit to the Tombs of Al-Kurru is a must-do before wrapping up your visit to the land of the Black Pharaohs. Only two tombs are opened to visitors, that of King Tanwetamani, Taharqa's successor and nephew, and that of Tanwetamani's mother Qalhata. Both include fabulous paintings that enjoy a great level of preservation.

Around AD 350 the area was invaded by the Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum and the kingdom collapsed. Eventually three smaller kingdoms replaced it: northernmost was Nobatia between the first and second cataract of the Nile River, with its capital at Pachoras (modern day Faras); in the middle was Makuria, with its capital at Old Dongola; and southernmost was Alodia, with its capital at Soba (near Khartoum). King Silky of Nobatia crushed the Blemmyes, and recorded his victory in a Greek inscription carved in the wall of the temple of Talmis (modern Kalabsha) around AD 500.

While bishop Athanasius of Alexandria consecrated one Marcus as bishop of Philae before his death in 373, showing that Christianity had penetrated the region by the 4th century, John of Ephesus records that a Monophysite priest named Julian converted the king and his nobles of Nobatia around 545. John of Ephesus also writes that the kingdom of Alodia was converted around 569. However, John of Biclarum records that the kingdom of Makuria was converted to Catholicism the same year, suggesting that John of Ephesus might be mistaken. Further doubt is cast on John's testimony by an entry in the chronicle of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria Eutychius, which states that in 719 the church of Nubia transferred its allegiance from the Greek to the Coptic Church.

By the 7th century Makuria expanded becoming the dominant power in the region. It was strong enough to halt the southern expansion of Islam after the Arabs had taken Egypt. After several failed invasions the new rulers agreed to a treaty with Dongola allowing for peaceful coexistence and trade. This treaty held for six hundred years. Over time the influx of Arab traders introduced Islam to Nubia and it gradually supplanted Christianity. While there are records of a bishop at Qasr Ibrim in 1372, his see had come to include that located at Faras. It is also clear that the cathedral of Dongola had been converted to a mosque in 1317.

The influx of Arabs and Nubians to Egypt and Sudan had contributed to the suppression of the Nubian identity following the collapse of the last Nubian kingdom around 1504. A major part of the modern Nubian population became totally Arabized and some claimed to be Arabs (Jaa'leen – the majority of Northern Sudanese – and some Donglawes in Sudan). A vast majority of the Nubian population is currently Muslim, and the Arabic language is their main medium of communication in addition to their indigenous old Nubian language. The unique characteristic of Nubian is shown in their culture (dress, dances, traditions, and music).

In the history of Sudan, the coming of Islam eventually changed the nature of Sudanese society and facilitated the division of the country into north and south. Islam also fostered political unity, economic growth, and educational development among its adherents; however, these benefits were restricted largely to urban and commercial centers.

The spread of Islam began shortly after the Prophet Muhammad's death in 632. By that time, he and his followers had converted most of Arabia's tribes and towns to Islam, which Muslims maintained united the individual believer, the state, and society under God's will. Islamic rulers, therefore, exercised temporal and religious authority. Islamic law (sharia), which was derived primarily from the Qur'an, encompassed all aspects of the lives of believers, who were called Muslims ("those who submit" to God's will).

Within a generation of Muhammad's death, Arab armies had carried Islam north and west from Arabia into North Africa. Muslims imposed political control over conquered territories in the name of the caliph (the Prophet's successor as supreme earthly leader of Islam). The Islamic armies won their first North African victory in 643 in Tripoli (in modern Libya). However, the Muslim subjugation of all of North Africa took about seventy-five years. The Arabs invaded Nubia in 642 and again in 652, when they laid siege to the city of Dunqulah and destroyed its cathedral. The Nubians put up a stout defense, however, causing the Arabs to accept an armistice and withdraw their forces.

Contacts between Nubians and Arabs long predated the coming of Islam, but the arabization of the Nile Valley was a gradual process that occurred over a period of nearly 1,000 years. Arab nomads continually wandered into the region in search of fresh pasturage, and Arab seafarers and merchants traded in Red Sea ports for spices and slaves. Intermarriage and assimilation also facilitated arabization. After the initial attempts at military conquest failed, the Arab commander in Egypt, Abd Allah ibn Saad, concluded the first in a series of regularly renewed treaties with the Nubians that, with only brief interruptions, governed relations between the two peoples for more than 600 years. This treaty was known as the baqt. So long as Arabs ruled Egypt, there was peace on the Nubian frontier; however, when non-Arabs (for example, the Mamluks) acquired control of the Nile Delta, tension arose in Upper Egypt.

The Arabs realized the commercial advantages of peaceful relations with Nubia and used the baqt to ensure that travel and trade proceeded unhindered across the frontier. The baqt also contained security arrangements whereby both parties agreed that neither would come to the defense of the other in the event of an attack by a third party. The baqt obliged both to exchange annual tribute as a goodwill symbol, the Nubians in slaves and the Arabs in grain. This formality was only a token of the trade that developed between the two, not only in these commodities but also in horses and manufactured goods brought to Nubia by the Arabs and in ivory, gold, gems, gum arabic, and cattle carried back by them to Egypt or shipped to Arabia.

Acceptance of the baqt did not indicate Nubian submission to the Arabs, but the treaty did impose conditions for Arab friendship that eventually permitted Arabs to achieve a privileged position in Nubia. Arab merchants established markets in Nubian towns to facilitate the exchange of grain and slaves. Arab engineers supervised the operation of mines east of the Nile in which they used slave labor to extract gold and emeralds. Muslim pilgrims en route to Mecca traveled across the Red Sea on ferries from Aydhab and Suakin, ports that also received cargoes bound from India to Egypt.

Traditional genealogies trace the ancestry of most of the Nile Valley's mixed population to Arab tribes that migrated into the region during this period. Even many non-Arabic-speaking groups claim descent from Arab forebears. The two most important Arabic-speaking groups to emerge in Nubia were the Ja'Alin and the Juhayna. Both showed physical continuity with the indigenous pre-Islamic population. The former claimed descent from the Quraysh, the Prophet Muhammad's tribe. Historically, the Jaali have been sedentary farmers and herders or townspeople settled along the Nile and in Al Jazirah.

The nomadic Juhayna comprised a family of tribes that included the Kababish, Baqqara, and Shukriya. They were descended from Arabs who migrated after the 13th century into an area that extended from the savanna and semidesert west of the Nile to the Abyssinian foothills east of the Blue Nile. Both groups formed a series of tribal shaykhdoms that succeeded the crumbling Christian Nubian kingdoms and that were in frequent conflict with one another and with neighboring non-Arabs. In some instances, as among the Beja, the indigenous people absorbed Arab migrants who settled among them. Beja ruling families later derived their legitimacy from their claims of Arab ancestry.

Although not all Muslims in the region were Arabic-speaking, acceptance of Islam facilitated the Arabizing process. There was no policy of proselytism, however. Islam penetrated the area over a long period of time through intermarriage and contacts with Arab merchants and settlers.

At the same time that the Ottomans brought northern Nubia into their orbit, a new power, the Funj, had risen in southern Nubia and had supplanted the remnants of the old Christian kingdom of Alwa. In 1504 a Funj leader, Amara Dunqas, founded the Kingdom of Sennar. This Sultanate eventually became the keystone of the Funj Empire. By the mid-sixteenth century, Sennar controlled Al Jazirah and commanded the allegiance of vassal states and tribal districts north to the third cataract and south to the rainforests.

The Funj state included a loose confederation of sultanates and dependent tribal chieftaincies drawn together under the suzerainty of Sennar's mek (sultan). As overlord, the mek received tribute, levied taxes, and called on his vassals to supply troops in time of war. Vassal states in turn relied on the mek to settle local disorders and to resolve internal disputes. The Funj stabilized the region and interposed a military bloc between the Arabs in the north, the Abyssinians in the east, and the non-Muslim blacks in the south.

The sultanate's economy depended on the role played by the Funj in the slave trade. Farming and herding also thrived in Al Jazirah and in the southern rainforests. Sennar apportioned tributary areas into tribal homelands (each one termed a dar; pl., dur), where the mek granted the local population the right to use arable land. The diverse groups that inhabited each dar eventually regarded themselves as units of tribes. Movement from one dar to another entailed a change in tribal identification. (Tribal distinctions in these areas in modern Sudan can be traced to this period.) The mek appointed a chieftain (nazir; pl., nawazir) to govern each dar. Nawazir administered dur according to customary law, paid tribute to the mek, and collected taxes. The mek also derived income from crown lands set aside for his use in each dar.

At the peak of its power in the mid-17th century, Sennar repulsed the northward advance of the Nilotic Shilluk people up the White Nile and compelled many of them to submit to Funj authority. After this victory, the mek Badi II Abu Duqn (1642-81) sought to centralize the government of the confederacy of Sennar. To implement this policy, Badi introduced a standing army of slave soldiers that would free Sennar from dependence on vassal sultans for military assistance and would provide the mek with the means to enforce his will. The move alienated the dynasty from the Funj warrior aristocracy, which in 1718 deposed the reigning mek and placed one of their own ranks on the throne of Sennar. The mid-18th century witnessed another brief period of expansion when the Funj turned back an Abyssinian invasion, defeated the Fur, and took control of much of Kurdufan. But civil war and the demands of defending the sultanate had overextended the warrior society's resources and sapped its strength.

Another reason for Sennar's decline may have been the growing influence of its hereditary viziers (chancellors), chiefs of a non-Funj tributary tribe who managed court affairs. In 1761 the vizier Muhammad Abu al Kaylak, who had led the Funj army in wars, carried out a palace coup, relegating the sultan to a figurehead role. Sennar's hold over its vassals diminished, and by the early 19th century more remote areas ceased to recognize even the nominal authority of the mek.

Darfur was the Fur homeland. Renowned as cavalrymen, Fur clans frequently allied with or opposed their kin, the Kanuri of Borno, in modern Nigeria. After a period of disorder in the sixteenth century, during which the region was briefly subject to the Bornu Empire, the leader of the Keira clan, Sulayman Solong (1596-1637), supplanted a rival clan and became Darfur's first sultan.

Sulayman Solong decreed Islam to be the sultanate's official religion. However, large-scale religious conversions did not occur until the reign of Ahmad Bakr (1682-1722), who imported teachers, built mosques, and compelled his subjects to become Muslims. In the eighteenth century, several sultans consolidated the dynasty's hold on Darfur, established a capital at Al Fashir, and contested the Funj for control of Kurdufan.

The sultans operated the slave trade as a monopoly. They levied taxes on traders and export duties on slaves sent to Egypt, and took a share of the slaves brought into Darfur. Some household slaves advanced to prominent positions in the courts of sultans, and the power exercised by these slaves provoked a violent reaction among the traditional class of Fur officeholders in the late eighteenth century. The rivalry between the slave and traditional elites caused recurrent unrest throughout the next century.

The Funj were originally non-Muslims, but the aristocracy soon adopted Islam and, although they retained many traditional African customs, remained nominal Muslims. The conversion was largely the work of a handful of Islamic missionaries who came to the Sudan from the larger Muslim world. The great success of these missionaries, however, was not among the Funj themselves but among the Arabized Nubian population settled along the Nile.

Among these villagers the missionaries instilled a deep devotion to Islam that appears to have been conspicuously absent among the nomadic Arabs who first reached the Sudan after the collapse of the kingdom of Maqurrah. One early missionary was Ghulam Allah ibn 'A'id from the Yemen, who settled at Dunqulah in the 14th century.

He was followed in the 15th century by Hamad Abu Danana, who appears to have emphasized the way to God through mystical exercises rather than through the more orthodox interpretations of the Qur'an taught by Ghulam Allah.

The spread of Islam was advanced in the 16th century, when the hegemony of the Funj enhanced security. In the 16th and 17th centuries, numerous schools of religious learning were founded along the White Nile, and the Shayqiyah confederacy was converted. Many of the more famous Sudanese missionaries who followed them were Sufi holy men, members of influential religious brotherhoods who sought the way to God through mystical contemplation.

The Sufi brotherhoods themselves played a vital role in linking the Sudan to the larger world of Islam beyond the Nile valley. Although the fervor of Sudanese Islam waned after 1700, the great reform movements that shook the Muslim world in the late 18th and early 19th centuries produced a revivalist spirit among the Sufi brotherhoods, giving rise to a new order, the Mirghaniyah or Khatmiyah, later one of the strongest in the modern Sudan.

These men, called faqihs, attracted a following by their teachings and piety and laid the foundations for a long line of indigenous Sudanese holy men. The latter passed on the way to God taught them by their masters, or founded their own religious schools, or, if extraordinarily successful, gathered their own following into a religious order. The faqihs played a vital role in educating their followers and helped place them in the highest positions of government, by which they were able to spread Islam and the influence of their respective brotherhoods.

The faqihs held a religious monopoly until the introduction, under Egyptian-Ottoman rule (see below), of an official hierarchy of jurists and scholars, the 'ulama', whose orthodox legalistic conception of Islam was as alien to the Sudanese as were their origins.

This disparity between the mystical, traditional faqihs, close to the Sudanese, if not of them, and the orthodox, Islamic jurists, aloof, if not actually part of the government bureaucracy, created a rivalry that in the past produced open hostility in times of trouble and sullen suspicion in times of peace. Recently, this schism has diminished; the faqih continues his customary practices unmolested, while the Sudanese have acknowledged the position of the 'ulama' in society.

Muhammad Ali and his successors

In July 1820, Muhammad 'Ali, viceroy of Egypt under the Ottoman Turks, sent an army under his son Isma'il to conquer the Sudan. Muhammad 'Ali was interested in the gold and slaves that the Sudan could provide and wished to control the vast hinterland south of Egypt. By 1821 the Funj and the sultan of Darfur had surrendered to his forces, and the Nilotic Sudan from Nubia to the Ethiopian foothills and from the 'Atbarah River to Darfur became part of his expanding empire.

The collection of taxes under Muhammad 'Ali's regime amounted to virtual confiscation of gold, livestock, and slaves, and opposition to his rule became intense, eventually erupting into rebellion and the murder of Isma'il and his bodyguard. But the rebels lacked leadership and coordination, and their revolt was brutally suppressed. A sullen hostility in the Sudanese was met by continued repression until the appointment of 'Ali Khurshid Agha as governor-general in 1826.

His administration marked a new era in Egyptian-Sudanese relations. He reduced taxes and consulted the Sudanese through the respected Sudanese leader 'Abd al-Qadir wad az-Zayn. Letters of amnesty were granted to fugitives. A more equitable system of taxation was implemented, and the support of the powerful class of holy men and sheikhs (tribal chiefs) for the administration was obtained by exempting them from taxation.

But 'Ali Khurshid was not content merely to restore the Sudan to its previous condition. Under his initiative trade routes were protected and expanded, Khartoum was developed as the administrative capital, and a host of agricultural and technical improvements were undertaken. When he retired to Cairo in 1838, Khurshid left a prosperous and contented country behind him.

His successor, Ahmad Pasha Abu Widan, with but few exceptions, continued his policies and made it his primary concern to root out official corruption. Abu Widan dealt ruthlessly with offenders or those who sought to thwart his schemes to reorganize taxation. He was particularly fond of the army, which reaped the benefits of regular pay and tolerable conditions in return for the brunt of the expansion and consolidation of Egyptian administration in Kassala and among the Baqqarah Arabs of southern Kordofan. Muhammad 'Ali, suspecting Abu Widan of disloyalty, recalled him to Cairo in the autumn of 1843, but he died mysteriously, many believed of poison, before he left the Sudan.

During the next two decades the country stagnated because of ineffective government at Khartoum and vacillation by the viceroys at Cairo. If the successors of Abu Widan possessed administrative talent, they were seldom able to demonstrate it. No governor-general held office long enough to introduce his own plans, let alone carry on those of his predecessor.

New schemes were never begun, and old projects were allowed to languish. Without direction the army and the bureaucracy became demoralized and indifferent, while the Sudanese became disgruntled with the government. In 1856 the viceroy Sa'id Pasha visited the Sudan and, shocked by what he saw, contemplated abandoning it altogether. Instead, he abolished the office of governor-general and had each Sudanese province report directly to the viceregal authority in Cairo. This state of affairs persisted until the more dynamic viceroy Isma'il took over the guidance of Egyptian and Sudanese affairs in 1862.

During these quiescent decades, however, two ominous developments began that presaged future problems. Reacting to pressure from the Western powers, particularly Great Britain, the governor-general of the Sudan was ordered to halt the slave trade. But not even the viceroy himself could overcome established custom with the stroke of a pen and the erection of a few police posts.

If the restriction of the slave trade precipitated resistance among the Sudanese, the appointment of Christian officials to the administration and the expansion of the European Christian community in the Sudan caused open resentment. European merchants, mostly of Mediterranean origin, were either ignored or tolerated by the Sudanese and confined their contacts to compatriots within their own community and to the Turko-Egyptian officials whose manners and dress they frequently adopted. They became a powerful and influential group, whose lasting contribution to the Sudan was to take the lead in opening the White Nile and the southern Sudan to navigation and commerce after Muhammad 'Ali had abolished state trading monopolies in the Sudan in 1838 under pressure from the European powers.

In 1863, Isma'il Pasha became viceroy of Egypt. Educated in Egypt, Vienna, and Paris, Isma'il had absorbed the European interest in overseas adventures as well as Muhammad 'Ali's desire for imperial expansion and had imaginative schemes for transforming Egypt and the Sudan into a modern state by employing Western technology.

First he hoped to acquire the rest of the Nile basin, including the southern Sudan and the Bantu states by the great lakes of central Africa. To finance this vast undertaking, and his projects for the modernization of Egypt itself, Isma'il turned to the capital-rich nations of western Europe, where investors were willing to risk their savings at high rates of interest in the cause of Egyptian and African development.

But such funds would be attracted only as long as Isma'il demonstrated his interest in reform by intensifying the campaign against the slave trade in the Sudan. Isma'il needed no encouragement, for he required the diplomatic and financial support of the European powers in his efforts to modernize Egypt and expand his empire. Thus, these two major themes of Isma'il's rule of the Nilotic Sudan--imperial expansion and the suppression of the slave trade--became intertwined, culminating in a third major development, the introduction of an ever-increasing number of European Christians to carry out the task of modernization.

In 1869 Isma'il commissioned the Englishman Samuel Baker to lead an expedition up the White Nile to establish Egyptian hegemony over the equatorial regions of central Africa and to curtail the slave trade on the upper Nile. Baker remained in equatorial Africa until 1873, where he established the Equatoria province as part of the Egyptian Sudan. He had extended Egyptian power and curbed the slave traders on the Nile, but he had also alienated certain African tribes and, being a rather tactless Christian, Isma'il's Muslim administrators as well. Moreover, Baker had struck only at the Nilotic slave trade.

To the west, on the vast plains of the Bahr Al-Ghazal (now a state of the Republic of The Sudan), slave merchants had established enormous empires with stations garrisoned by slave soldiers.

From these stations the long lines of human chattels were sent overland through Darfur and Kordofan to the slave markets of the northern Sudan, Egypt, and Arabia. Not only did the firearms of the Khartoumers (as the traders were called) establish their supremacy over the peoples of the interior but also those merchants with the strongest resources gradually swallowed up lesser traders until virtually the whole of the Bahr Al-Ghazal was controlled by the greatest slaver of them all, az-Zubayr Rahma Mansur, more commonly known as Zubayr (or Zobeir) Pasha.

So powerful had he become that in 1873, the year Baker retired from the Sudan, the Egyptian viceroy (now called the khedive) appointed Zubayr governor of the Bahr Al-Ghazal. Isma'il's officials had failed to destroy Zubayr as Baker had crushed the slavers east of the Nile, and to elevate Zubayr to the governorship appeared the only way to establish at least the nominal sovereignty of Cairo over that enormous province. Thus, the agents of Zubayr continued to pillage the Bahr Al-Ghazal under the Egyptian flag, while officially Egypt extended its dominion to the tropical rainforests of the Congo region. Zubayr remained in detention in Cairo.

Isma'il next offered the governorship of the Equatoria province to another Englishman, Charles George Gordon, who in China had won fame and the sobriquet Chinese Gordon. Gordon arrived in Equatoria in 1874. His object was the same as Baker's--to consolidate Egyptian authority in Equatoria and to establish Egyptian sovereignty over the kingdoms of the great East African lakes. He achieved some success in the former and none in the latter. When Gordon retired from Equatoria, the lake kingdoms remained stubbornly independent.

In 1877 Isma'il appointed Gordon governor-general of the Sudan. Gordon was a European and a Christian. He returned to the Sudan to lead a crusade against the slave trade, and, to assist him in this humanitarian enterprise, he surrounded himself with a cadre of European and American Christian officials. In 1877 Isma'il had signed the Anglo-Egyptian Slave Trade Convention, which provided for the termination of the sale and purchase of slaves in the Sudan by 1880. Gordon set out to fulfill the terms of this treaty, and in whirlwind tours through the country he broke up the markets and imprisoned the traders. His European subordinates did the same in the provinces.

Gordon's crusading zeal blinded him to his invidious position as a Christian in a Muslim land and obscured from him the social and economic effects of arbitrary repression. Not only did his campaign create a crisis in the Sudan's economy but the Sudanese soon came to believe that the crusade, led by European Christians, violated the principles and traditions of Islam.

By 1879 a strong current of reaction against Gordon's reforms was running through the country. The powerful slave-trading interests had, of course, turned against the administration, while the ordinary villagers and nomads, who habitually blamed the government for any difficulties, were quick to associate economic depression with Gordon's Christianity. And then suddenly, in the middle of rising discontent in the Sudan, Isma'il's financial position collapsed. In difficulties for years, he could now no longer pay the interest on the Egyptian debt, and an international commission was appointed by the European powers to oversee Egyptian finances. After 16 years of glorious spending, Isma'il sailed away into exile. Gordon resigned.

Gordon left a perilous situation in the Sudan. The Sudanese were confused and dissatisfied. Many of the ablest senior officials, both European and Egyptian, had been dismissed by Gordon, departed with him, or died in his service. Castigated and ignored by Gordon, the bureaucracy had lapsed into apathy. Moreover, the office of governor-general, on which the administration was so dependent, devolved upon Muhammad Ra'uf Pasha, a mild man, ill-suited to stem the current of discontent or to shore up the structure of Egyptian rule, particularly when he could no longer count on Egyptian resources. Such then was the Sudan in June of 1881 when Muhammad Ahmad declared himself to be the Mahdi ("the divinely guided one").

Muhammad Ahmad ibn 'Abd Allah was the son of a Dunqulahwi boatbuilder who claimed descent from the Prophet Muhammad. Deeply religious from his youth, he was educated in one of the Sufi orders, the Sammaniyah, but he later secluded himself on Aba Island in the White Nile to practice religious asceticism.

In 1880 he toured Kordofan, where he learned of the discontent of the people and observed those actions of the government that he could not reconcile with his own religious beliefs. Upon his return to Aba Island he clearly viewed himself as a mujaddid, a renewer of the Muslim faith, his mission to reform Islam and return it to the pristine form practiced by the Prophet.

To Muhammad Ahmad the orthodox 'ulama' who supported the administration were no less infidels than Christians, and, when he later lashed out against misgovernment, he was referring as much to the theological heresy as to secular maladministration.

Once he had proclaimed himself Mahdi (a title traditionally used by Islamic religious reformers), Muhammad Ahmad was regarded by the Sudanese as an eschatological figure, one who foreshadows the end of an age of darkness (which happened to coincide with the end of the 13th Muslim century) and heralds the beginnings of a new era of light and righteousness. Thus, as a divinely guided reformer and symbol, Muhammad Ahmad fulfilled the requirements of Mahdi in the eyes of his supporters.

Surrounding the Mahdi were his followers, the ansar, and foremost among them was 'Abd Allah ibn Muhammad, the caliph (khalifah; "deputy"), who came from the Ta'a'ishah tribe of the Baqqarah Arabs and who assumed the leadership of the Mahdist state upon the death of Muhammad Ahmad.

The holy men, the faqihs, who for long had lamented the sorry state of religion in the Sudan brought on by the legalistic and unappealing orthodoxy of the Egyptians, looked to the Mahdi to purge the Sudan of the faithless ones. Also in his following, more numerous and powerful than the holy men, were the merchants formerly connected with the slave trade. All had suffered from Gordon's campaign against the trade, and all now hoped to reassert their economic position under the banner of religious war. Neither of these groups, however, could have carried out a revolution by themselves.

The third and vital participants were the Baqqarah Arabs, the cattle nomads of Kordofan and Darfur who hated taxes and despised government. They formed the shock troops of the Mahdist revolutionary army, whose enthusiasm and numbers made up for its primitive technology. Moreover, the government itself only managed to enhance the prestige of the Mahdi by its fumbling attempts to arrest him and proscribe his movement.

By September 1882, the Mahdists controlled all of Kordofan and at Shaykan on Nov. 5, 1883, destroyed an Egyptian army of 10,000 men under the command of a British colonel. After Shaykan, the Sudan was lost, and not even the heroic leadership of Gordon, who was hastily sent to Khartoum, could save the Sudan for Egypt. On Jan. 26, 1885, the Mahdists captured Khartoum and massacred Gordon and the defenders.

Five months after the fall of Khartoum, the Mahdi suddenly died on June 22, 1885. He was succeeded by the Khalifah 'Abd Allah. The Khalifah's first task was to secure his own precarious position among the competing factions in the Mahdist state. He frustrated a conspiracy by the Mahdi's relatives and disarmed the personal retinues of his leading rivals in Omdurman, the Mahdist capital of the Sudan. Having curtailed the threats to his rule, the Khalifah sought to accomplish the Mahdi's dream of a universal jihad (holy war) to reform Islam throughout the Muslim world.

With a zeal compounded from a genuine wish to carry out religious reform, a desire for military victory and personal power, and an appalling ignorance of the world beyond the Sudan, the forces of the Khalifah marched to the four points of the compass to spread Mahdism and extend the domains of the Mahdist state. By 1889 this expansionist drive was spent. In the west the Mahdist armies had achieved only an unstable occupation of Darfur.

In the east they had defeated the Ethiopians, but the victory produced no permanent gain. In the southern Sudan the Mahdists had scored some initial successes but were driven from the upper Nile in 1897 by the forces of the Congo Free State of Leopold II of Belgium.

On the Egyptian frontier in the north the jihad met its worst defeat at Tushki in August 1889, when an Anglo-Egyptian army under General F.W. (later Baron) Grenfell destroyed a Mahdist army led by 'Abd ar-Rahman an-Nujumi.

The Mahdist state had squandered its resources on the jihad, and a period of consolidation and contraction followed, necessitated by a sequence of bad harvests resulting in famine, epidemic, and death.

Between 1889 and 1892 the Sudan suffered its most devastating and terrible years, as the Sudanese sought to survive on their shriveled crops and emaciated herds. After 1892 the harvests improved, and food was no longer in short supply.

Moreover, the autocracy of the Khalifah had become increasingly acceptable to most Sudanese, and, having tempered his own despotism and eliminated the gross defects of his administration he too received the widespread acceptance, if not devotion, that the Sudanese had accorded the Mahdi.

In spite of its many defects, the Khalifah's administration served the Sudan better than its many detractors would admit. Certainly the Khalifah's government was autocratic, but, while autocracy may be repugnant to European democrats, it was not only understandable to the Sudanese but appealed to their deepest feelings and attitudes formed by tribe, religion, and past experience with the centralized authoritarianism of the Turks. For them, the Khalifah was equal to the task of governing bequeathed him by the Mahdi.

Only when confronted by new forces from the outside world, of which he was ignorant, did 'Abd Allah's abilities fail him. His belief in Mahdism, his reliance on the superb courage and military skill of the ansar, and his own ability to rally them against an alien invader were simply insufficient to preserve his independent Islamic state against the overwhelming technological superiority of Britain. And, as the 19th century drew to a close, the rival imperialisms of the European powers brought the full force of this technological supremacy against the Mahdist state.

British forces invaded and occupied Egypt in 1882 to put down a nationalist revolution hostile to foreign interests and remained there to prevent any further threat to the khedive's government or the possible intervention of another European power. The consequences of this were far-reaching. A permanent British occupation of Egypt required the inviolability of the Nile waters without which Egypt could not survive, not from any African state, who did not possess the technical resources to interfere with them, but from rival European powers, who could. Consequently, the British government, by diplomacy and military maneuvers, negotiated agreements with the Italians and the Germans to keep them out of the Nile valley.

They were less successful with the French, who wanted them to withdraw from Egypt. Once it became apparent that the British were determined to remain, the French cast about for means to force the British from the Nile valley; in 1893 an elaborate plan was concocted by which a French expedition would march across Africa from the west coast to Fashoda (Kodok) on the upper Nile, where it was believed a dam could be constructed to obstruct the flow of the Nile waters. After inordinate delays, the French Nile expedition set out for Africa in June 1896, under the command of Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand.

As reports reached London during 1896 and 1897 of Marchand's march to Fashoda, Britain's inability to insulate the Nile valley became embarrassingly exposed. British officials desperately tried one scheme after another to beat the French to Fashoda.

They all failed, and by the autumn of 1897 British authorities had come to the reluctant conclusion that the conquest of the Sudan was necessary to protect the Nile waters from French encroachment. In October an Anglo-Egyptian army under the command of General Sir Horatio Herbert Kitchener was ordered to invade the Sudan.

Kitchener pushed steadily but cautiously up the Nile. His Anglo-Egyptian forces defeated a large Mahdist army at the 'Atbarah River on April 8, 1898. Then, after spending four months preparing for the final advance to Omdurman, Kitchener's army of about 25,000 troops met the massed 60,000-man army of the Khalifah outside the city on Sept. 2, 1898. By midday the Battle of Omdurman was over.

The Mahdists were decisively defeated with heavy losses, and the Khalifah fled, to be killed nearly a year later. Kitchener did not long remain at Omdurman but pressed up the Nile to Fashoda with a small flotilla. There on Sept. 18, 1898, he met Captain Marchand, who declined to withdraw--the long-expected Fashoda crisis had begun. Both the French and British governments prepared for war. Neither the French army nor the navy was in any condition to fight, however, and the French were forced to give way. An Anglo-French agreement of March 1899 stipulated that French expansion eastward in Africa would stop at the Nile watershed.

The early years of British rule

Having conquered the Sudan, the British now had to govern it. But the administration of this vast land was complicated by the legal and diplomatic problems that had accompanied the conquest. The Sudan campaigns had been undertaken by the British to protect their imperial position as well as the Nile waters, yet the Egyptian treasury had borne the greater part of the expense, and Egyptian troops had far outnumbered those of Britain in the Anglo-Egyptian army.

The British, however, did not simply want to hand the Sudan over to Egyptian rule; most Englishmen were convinced that the Mahdiyah was the result of 60 years of Egyptian oppression.

To resolve this dilemma the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was declared in 1899, whereby the Sudan was given separate political status in which sovereignty was jointly shared by the khedive and the British crown, and the Egyptian and the British flags were flown side by side. The military and civil government of the Sudan was invested in a governor-general appointed by the khedive of Egypt but nominated by the British government. In reality, there was no equal partnership between Britain and Egypt in the Sudan.

From the first the British dominated the condominium and set about pacifying the countryside and suppressing local religious uprisings, which created insecurity among British officials but never posed a major threat to their rule. The north was quickly pacified and modern improvements were introduced under the aegis of civilian administrators, who began to replace the military as early as 1900. In the south, resistance to British rule was more prolonged; administration there was confined to keeping the peace rather than making any serious attempts at modernization.

The first governor-general was Lord Kitchener himself, but in 1899 his former aide, Sir Reginald Wingate, was appointed to succeed him. Wingate knew the Sudan well and during his long tenure as governor-general (1899-1916) became devoted to its people and their prosperity. His tolerance and trust in the Sudanese resulted in policies that did much to establish confidence in Christian British rule by a devoutly Muslim, Arab-oriented people.

Modernization was slow at first. Taxes were purposely kept light, and the government consequently had few funds available for development. In fact, the Sudan remained dependent on Egyptian subsidies for many years. Nevertheless, railways, telegraph, and steamer services were expanded, particularly in Al-Jazirah, in order to launch the great cotton-growing scheme that remains today the backbone of The Sudan's economy.

In addition, technical and primary schools were established, including the Gordon Memorial College, which opened in 1902 and soon began to graduate a Western-educated elite that was gradually drawn away from the traditional political and social framework. Scorned by the British officials, who preferred the illiterate but contented fathers to the ill-educated, rebellious sons, and adrift from their own customary tribal and religious affiliations, these Sudanese turned for encouragement to Egyptian nationalists; from that association Sudanese nationalism in this century was born.

Its first manifestations occurred in 1921, when 'Ali 'Abd al-Latif founded the United Tribes Society and was arrested for nationalist agitation. In 1924 he formed the White Flag League, dedicated to driving the British from the Sudan. Demonstrations followed in Khartoum in June and August and were suppressed. When the governor-general, Sir Lee Stack, was assassinated in Cairo on Nov. 19, 1924, the British forced the Egyptians to withdraw from the Sudan and annihilated a Sudanese battalion that mutinied in support of the Egyptians. The Sudanese revolt was ended, and British rule remained unchallenged until after World War II.

In 1936 Britain and Egypt had reached a partial accord in the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty that enabled Egyptian officials to return to the Sudan. Although the traditional Sudanese sheikhs and chiefs remained indifferent to the fact that they had not been consulted in the negotiations over this treaty, the educated Sudanese elite were resentful that neither Britain nor Egypt had bothered to solicit their opinions. Thus, they began to express their grievances through the Graduates' General Congress, which had been established as an alumni association of Gordon Memorial College and soon embraced all educated Sudanese.

At first, the Graduates' General Congress confined its interests to social and educational activities, but with Egyptian support the organization demanded recognition by the British to act as the spokesman for Sudanese nationalism. The Sudan government refused, and the Congress split into two groups: a moderate majority prepared to accept the good faith of the government, and a radical minority, led by Isma'il al-Azhari, which turned to Egypt. By 1943 Azhari and his supporters had won control of the Congress and organized the Ashiqqa' (Brothers), the first genuine political party in the Sudan. Seeing the initiative pass to the militants, the moderates formed the Ummah (Nation) Party under the patronage of Sayyid 'Abd ar-Rahman al-Mahdi, the posthumous son of the Mahdi, with the intention of cooperating with the British toward independence.

Sayyid 'Abd ar-Rahman had inherited the allegiance of the thousands of Sudanese who had followed his father. He now sought to combine to his own advantage this power and influence with the ideology of the Ummah. His principal rival was Sayyid 'Ali al-Mirghani, the leader of the Khatmiyah brotherhood. Although he personally remained aloof from politics, Sayyid 'Ali threw his support to Azhari. The competition between the Azhari-Khatmiyah faction--remodeled in 1951 as the National Unionist Party (NUP)--and the Ummah-Mahdist group quickly rekindled old suspicions and deep-seated hatreds that soured Sudanese politics for years and eventually strangled parliamentary government. These sectarian religious elites virtually controlled The Sudan's political parties until the last decade of the 20th century, stultifying any attempt to democratize the country or to include the millions of Sudanese remote from Khartoum in the political process.

Although the Sudanese government had crushed the initial hopes of the congress, the British officials were well aware of the pervasive power of nationalism among the elite and sought to introduce new institutions to associate the Sudanese more closely with the task of governing. An Advisory Council was established for the northern Sudan consisting of the governor-general and 28 Sudanese, but Sudanese nationalists soon began to agitate to transform the Advisory Council into a legislative one that would include the southern Sudan. The British had facilitated their control of the Sudan by segregating the animist or Christian Africans who predominated in the south from the Muslim Arabs who were predominant in the north. The decision to establish a legislative council forced the British to abandon this policy; in 1947 they instituted southern participation in the legislative council.

The creation of this council produced a strong reaction on the part of the Egyptian government, which in October 1951 unilaterally abrogated the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 and proclaimed Egyptian rule over the Sudan. These hasty and ill-considered actions only managed to alienate the Sudanese from Egypt until the Nasser-Naguib revolution in July 1952 placed men with more understanding of Sudanese aspirations in power in Cairo.