The Maori people are the indigenous people of New Zealand. Their name 'Maori' derives from Ma-Uri, meaning 'Children of Heaven'. Their nickname is 'Vikings of the Sunrise', because they were fierce warriors. Originally, they were hunters, but soon became peasants, living off agriculture. Today, approximately 300,000 Maori live mainly in cities, but remain closely connected to their tribes and ancient traditions.

Maori are Polynesian and comprise about 8% of the country's population. Maoritanga is the native language which is related to Tahitian and Hawaiian. It is believed that the Maori migrated from Polynesia in canoes in the 9th century to the 13th century.

The word Polynesia, which means many islands, comes from the Greek words 'poly' which means 'many' and 'nesos' which means 'island'. Polynesia stretches in a huge triangle from New Zealand in the southwest to Easter Island, 8,000 kilometres away in the southeast and up to Hawaii at its northern point. The Polynesian people are lighter skinned and are generally taller than the Melanesian and Micronesian people.

Over several centuries in isolation, the Maori developed a unique culture with their own language, a rich mythology, distinctive crafts and performing arts. They formed a tribal society based on Polynesian social customs and organization. Horticulture flourished using plants they introduced, and after about 1450 a prominent warrior culture emerged.

The arrival of Europeans to New Zealand starting from the 17th century brought enormous change to the Maori way of life. Maori people gradually adopted many aspects of Western society and culture.

Initial relations between Maori and Europeans were largely amicable, and with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 the two cultures coexisted as part of a new British colony. However, rising tensions over disputed land sales led to conflict in the 1860s. Social upheaval, decades of conflict and epidemics of disease took a devastating toll on the Maori population.

But by the start of the 20th century the Maori population had begun to recover, and efforts were made to increase their standing in wider New Zealand society. A marked Maori cultural revival gathered pace in the 1960s and is continuing.

In 2010, there were an estimated 660,000 Maori in New Zealand, making up roughly 15% of the national population. They are the second-largest ethnic group in New Zealand, after European New Zealanders ("Pakeha"). In addition there are over 100,000 Maori living in Australia.

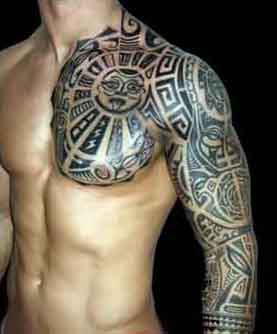

Much of New Zealand's culture is derived from Maori and early British settlers. Early European art was dominated by landscapes and to a lesser extent portraits of Maori. A recent resurgence of Maori culture has seen their traditional arts of carving, weaving and tattooing become more mainstream. Many artists now combine Maori and Western techniques to create unique art forms.

The Maori language is spoken to some extent by about a quarter of all Maori, and 4% of the total population, although many New Zealanders regularly use Maori words and expressions in normal speech. Maori are active in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, with distinct representation in areas such as media, politics and sport.

The Maori face significant economic and social obstacles, with lower life expectancies and incomes compared with other New Zealand ethnic groups, in addition to higher levels of crime, health problems and educational under-achievement. Socioeconomic initiatives have been implemented aimed at closing the gap between Maori and other New Zealanders. Political redress for historical grievances is also ongoing.

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses (the North Island and the South Island) and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some 1,500 kilometres (900 mi) east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly 1,000 kilometres (600 mi) south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga. Due to its remoteness, it was one of the last lands to be settled by humans.

During its long isolation New Zealand developed a distinctive fauna dominated by birds, many of which became extinct after the arrival of humans and introduced mammals. With a mild maritime climate, the land was mostly covered in forest. The country's varied topography and its sharp mountain peaks owe much to the uplift of land and volcanic eruptions caused by the Pacific and Indo-Australian Plates clashing underfoot.

Polynesians settled New Zealand in 1250-1300 AD and developed a distinctive Maori culture, and Europeans first made contact in 1642 AD. The introduction of potatoes and muskets triggered upheaval among Maori early during the 19th century, which led to the inter-tribal Musket Wars.

In 1840 the British and Maori signed a treaty making New Zealand a colony of the British Empire. Immigrant numbers increased sharply and conflicts escalated into the Land Wars, which resulted in much Maori land being confiscated in the mid North Island. Economic depressions were followed by periods of political reform, with women gaining the vote during the 1890s, and a welfare state being established from the 1930s.

After World War II, New Zealand joined Australia and the United States in the ANZUS security treaty, although the United States later suspended the treaty after New Zealand banned nuclear weapons. New Zealanders enjoyed one of the highest standards of living in the world in the 1950s, but the 1970s saw a deep recession, worsened by oil shocks and the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community.

The country underwent major economic changes during the 1980s, which transformed it from a protectionist to a liberalized free-trade economy. Markets for New Zealand's agricultural exports have diversified greatly since the 1970s, with once-dominant exports of wool being overtaken by dairy products, meat, and recently wine.

The majority of New Zealand's population is of European descent; the indigenous Maori are the largest minority, followed by Asians and non-Maori Polynesians. English, Maori and New Zealand Sign Language are the official languages, with English predominant.

Much of New Zealand's culture is derived from Maori and early British settlers. Early European art was dominated by landscapes and to a lesser extent portraits of Maori. A recent resurgence of Maori culture has seen their traditional arts of carving, weaving and tattooing become more mainstream. Many artists now combine Maori and Western techniques to create unique art forms. The country's culture has also been broadened by globalization and increased immigration from the Pacific Islands and Asia. New Zealand's diverse landscape provides many opportunities for outdoor pursuits and has provided the backdrop for a number of big budget movies.

New Zealand is organized into 11 regional councils and 67 territorial authorities for local government purposes; these have less autonomy than the country's long defunct provinces did. Nationally, executive political power is exercised by the Cabinet, led by the Prime Minister. Queen Elizabeth II is the country's head of state and is represented by a Governor-General.

The Queen's Realm of New Zealand also includes Tokelau (a dependent territory); the Cook Islands and Niue (self-governing but in free association); and the Ross Dependency, New Zealand's territorial claim in Antarctica. New Zealand is a member of the Pacific Islands Forum, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, United Nations, Commonwealth of Nations, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Today with natural disasters accelerating in the Pacific Ring of Fire, we pay attention to earthquake and volcanic activity in that area, which includes New Zealand.

Earthquakes occur in New Zealand as the country forms part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, which is geologically active. About 20,000 earthquakes, most of them minor, are recorded each year. About 200 of these are strong enough to be felt. As a result, New Zealand has very stringent building regulations.

Earthquake activity since 2009 have moved New Zealand closer to Australia, as reported in Associated Press.

The 2011 Christchurch earthquake was a magnitude 6.3 (ML) earthquake that struck the Canterbury region in New Zealand's South Island at 12:51 pm on Tuesday, 22 February 2011 local time (23:51 21 February UTC). The earthquake was centered 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) west of the town of Lyttelton, and 10 kilometres (6 mi) south-east of the centre of Christchurch, New Zealand's second-most populous city. It followed nearly six months after the magnitude 7.1 2010 Canterbury earthquake of 4 September 2010, which caused significant damage to Christchurch and the central Canterbury region, but no direct fatalities.

The volcanism of New Zealand has been responsible for many of the country's geographical features, especially in the North Island and the country's outlying islands. It has also claimed many lives. While the land's volcanic history dates back to before the Zealandia microcontinent rifted away from Gondwana 60-130 million years ago, activity continues today with minor eruptions occurring every few years. This recent activity is primarily due to the country's position on the boundary between the Indo-Australian and Pacific Plates, a part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, and particularly the subduction of the Pacific Plate under the Indo-Australian Plate. New Zealand's rocks record examples of almost every kind of volcanism observed on Earth, including some of the world's largest eruptions in geologically recent times.

As well as the direct effects of explosions, lava, and pyroclastic flows, volcanoes pose various hazards to the New Zealand populace. These include tsunamis, breakout floods and lahars from volcanically dammed lakes, ashfall, and other far field effects.

List of volcanoes in New Zealand

The Maori had many myths and legends regarding the land's volcanic mountains. Perhaps the most well known regards the location of Taranaki, Tongariro and Pihanga as they stand today. It is said that the other two volcanoes competed for the love of the beautiful Pihanga, and Taranaki lost. Defeated, Taranaki moved to its present location near New Plymouth.

Another legend recounts the exploits of Ngatoro-i-rangi, a tohunga (priest) who arrived from the ancestral Maori homeland, Hawaiki, on the Arawa waka (canoe). Traveling inland and looking southward from Lake Taupo, he decided to climb the mountains he saw there. He reached and began to climb the first mountain along with his slave Ngauruhoe, who had been traveling with him, and named the mountain Tongariro (the name literally means 'looking south'), whereupon the two were overcome by a blizzard carried by the cold south wind. Near death, Ngatoro-i-rangi called back to his two sisters, Kuiwai and Haungaroa, who had also come from Hawaiki but remained upon Whakaari/White Island, to send him sacred fire which they had brought from Hawaiki. This they did, sending the fire in the form of two taniwha (powerful spirits) named Te Pupu and Te Haeata by a subterranean passage to the top of Tongariro. The tracks of these two taniwha formed the line of geothermal fire which extends from the Pacific Ocean and beneath the Taupo Volcanic Zone, and is seen in the many volcanoes and hot springs extending from Whakaari to Tokaanu and up to the Tongariro massif. The fire arrived just in time to save Ngatoro-i-rangi from freezing to death, but Ngauruhoe was already dead by the time Ngatoro-i-rangi turned to give him the fire. For this reason the hole through which the fire ascended, the active cone of Tongariro, is now called Ngauruhoe.

The Moeraki Boulders are unusually large and spherical boulders lying along a stretch of Koekohe Beach on the wave cut Otago coast of New Zealand between Moeraki and Hampden. They occur scattered either as isolated or clusters of boulders within a stretch of beach where they have been protected in a scientific reserve. The erosion by wave action of mudstone, comprising local bedrock and landslides, frequently exposes embedded isolated boulders. These boulders are grey-colored septarian concretions, which have been exhumed from the mudstone enclosing them and concentrated on the beach by coastal erosion.

Local Maori legends explained the boulders as the remains of eel baskets, calabashes, and kumara washed ashore from the wreck of an Arai-te-uru, a large sailing canoe. This legend tells of the rocky shoals that extend seaward from Shag Point as being the petrified hull of this wreck and a nearby rocky promontory as being the body of the canoe's captain.

In 1848 W.B.D. Mantell sketched the beach and its boulders, more numerous than now. The picture is now in the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington. The boulders were described in 1850 colonial reports and numerous popular articles since that time. In more recent times they have become a popular tourist attraction, often described and pictured in numerous web pages and tourist guides.

Strange round nodules of solid stone are found on a beach in New Zealand. Are they concretion precipitated over eons? There are many anomalous objects buried in mountains, drowned in oceans or scattered across the landscape that are not adequately explained through conventional theories. In previous Picture of the Day articles, we have identified several unique sites where stone spheres have been discovered washing out of hillsides or embedded within a sandstone matrix.

40 kilometers south of Oamaru, New Zealand, is a beach where hundreds of calcium carbonate spheres have fallen out of a cliff face and rolled down into the water. They range in size from small nodules to giant balls over 4 meters in diameter. Said to be the result of slow growth around a nucleus, the spheres are referred to as concretions and are thought to be the result of tiny amounts of mineral precipitation taking place over 65 million years.

The most current reliable evidence strongly indicates that initial settlement of New Zealand occurred around 1280 CE. Previous dating of some Kiore (Polynesian rat) bones at 50-150 CE has now been shown to have been unreliable; new samples of bone (and now also of unequivocally rat-gnawed woody seed cases) match the 1280 CE date of the earliest archaeological sites and the beginning of sustained, anthropogenic deforestation.

Maori oral history describes the arrival of ancestors from Hawaiki, (the mythical homeland in tropical Polynesia), in large ocean-going waka. Migration accounts vary among tribes (iwi), whose members may identify with several waka in their genealogies or whakapapa.

No credible evidence exists of human settlement in New Zealand prior to the Polynesian voyagers. Compelling evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the first settlers came from east Polynesia and became the Maori. Language evolution studies and mitochondrial DNA evidence suggest that most Pacific populations originated from Taiwanese aborigines around 5,200 years ago (before Chinese colonization), moving down through Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

New Zealand colonized 1000 years later than previously thought PhysOrg - June 3, 2008

Polynesian settlers in New Zealand developed a distinct society over several hundred years. Social groups were tribal, with no unified society or single Maori identity until after the arrival of Europeans. Nevertheless, common elements could be found in all Maori groups in pre-European New Zealand, including a shared Polynesian heritage, a common basic language, familial associations, traditions of warfare, and similar mythologies and religious beliefs.

Most Maori lived in villages, which were inhabited by several whanau (extended families) who collectively formed a hapu (clan or subtribe). Members of a hapu cooperated with food production, gathering resources, raising families and defense. Maori society across New Zealand was broadly stratified into three classes of people: rangatira, chiefs and ruling families; tutu, commoners; and mokai, slaves. Tohunga also held special standing in their communities as specialists of revered arts, skills and esoteric knowledge.

Shared ancestry, intermarriage and trade strengthened relationships between different groups. Many hap with mutually-recognized shared ancestry formed iwi, or tribes, which were the largest social unit in Maori society. Hapu and iwi often united for expeditions to gather food and resources, or in times of conflict. In contrast, warfare developed as an integral part of traditional life, as different groups competed for food and resources, settled personal disputes, and sought to increase their prestige and authority.

The arrival of Europeans to New Zealand dates back to the 17th century, although it was not until the expeditions of James Cook over a hundred years later that any meaningful interactions occurred between Europeans and Maori. For Maori, the new arrivals brought opportunities for trade, which many groups embraced eagerly. Early European settlers introduced tools, weapons, clothing and foods to Maori across New Zealand, in exchange for resources, land and labour. Maori began selectively adopting elements of Western society during the 19th century, including European clothing and food, and later Western education, religion and architecture.

But as the 19th century wore on, relations between European colonial settlers and different Maori groups became increasingly strained. Tensions led to conflict in the 1860s, and the confiscation of millions of acres of Maori land by the New Zealand colonial government. Significant amounts of land were also purchased by the colonial government and later through the Native Land Court. Confiscations and land sales facilitated European expansion across New Zealand, but also drastically reduced the economic sustainability and social organization of many iwi. The 19th century also saw a dramatic decline in the Maori population across New Zealand, widely attributed to outbreaks of disease and a deterioration in living conditions.

By the start of the 20th century, a greater awareness had emerged of a unified Maori identity, particularly in comparison to Pakeha, who now overwhelmingly outnumbered the Maori as a whole. Maori and Pakeha societies remained largely separate - socially, culturally, economically and geographically - for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Nevertheless, Maori groups continued to engage with the government and in legal processes to increase their standing in - and ultimately further their incorporation into - wider New Zealand society.

Many Maori migrated to larger rural towns and cities during the Depression and post-WWII periods in search of employment, leaving rural communities depleted and disconnecting many urban Maori from their traditional social controls and tribal homelands. Yet while standards of living improved among Maori, they continued to lag behind Pakeha in areas such as health, income, skilled employment and access to higher levels of education. Maori leaders and government policymakers alike struggled to deal with social issues stemming from increased urban migration, including a shortage of housing and jobs, and a rise in urban crime, poverty and health problems.

While the arrival of Europeans had a profound impact on the Maori way of life, many aspects of traditional society have survived into the 21st century. Maori participate fully in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, leading largely Western lifestyles while also maintaining their own cultural and social customs. The traditional social strata of rangatira, tutu and mokai have all but disappeared from Maori society, while the roles of tohunga and kaumatua are still present. Traditional kinship ties are also actively maintained, and the whanau in particular remains an integral part of Maori life.

The earliest period, conventionally dated 1100-1300 CE, is known as the Archaic period. Archaeology has shown that Otago was the node of Maori cultural development during this time, and the majority of archaic settlements were on or within 10 km (6 mi) of the coast, though it was common to establish small temporary camps (whakaruruhau) far inland.

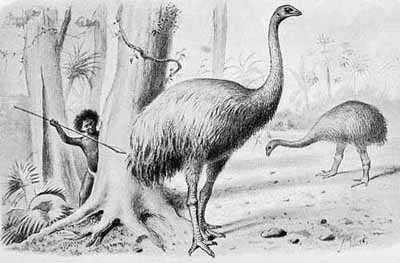

The settlements ranged in size from 40 people , the more common size, to 300-400, with 40 buildings at Shag River (Waihemo) mouth. The main food was moa hence the people are sometimes called the Moahunters. Up to 9.2 moa per week were killed, each producing an average 45 kg of meat, and the various species were probably wiped out within 200 years.

Moahunters extensively modified the natural vegetation by burning. Old soils show the thin horizons of carbon associated with this activity. The middens of the people reveal that they enjoyed a rich, varied diet of birds, fish, seals and shellfish. This period is remarkable for the lack of weapons and fortifications so typical of the later "classic" Maori, and for its distinctive "reel necklaces".

From this period onward around 32 species of birds became extinct either through over predation by the people and the kiore and kuri they introduced, repeated burning of the grassland or climate cooling, which appears to have occurred from about 1400-1450.

The best known archaic or Moahunter site is at Wairau Bar which has been extensively studied. The oldest skeleton was 30-32 years old with the mean age of skeletons 12-14 years. The people still practiced Polynesian-style burials. The teeth of all the older skeletons were worn to the gums. This is believed to be one reason for the low life expectancy.

Artifacts found were bone necklaces, Polynesian worked stone tool adze heads and the remains of small shelters. All of the older skeletons showed signs of a hard life with many having broken bones that had healed suggesting a balanced diet and a supportive community that had the resources to support severely injured family members. Due to tectonic forces some of this site is now under water.

-

New fossil evidence claims first discovery of taro in Maori gardens PhysOrg - April 10, 2019

The first discovery of Polynesian taro grown in Maori gardens in the 1400s can be claimed by an archaeological research project on Ahuahu-Great Mercury Island. During extensive field work on the private island off the eastern coast of Coromandel, palynologist Matthew Prebble of the Australian National University, alongside a team of archaeologists from the University of Auckland and Auckland War Memorial Museum, analyzed buried sediments from swamps which contained the pollen of taro and other leafy greens.

The cooling of the climate, a series of massive earthquakes in the South Island, tsunamis that destroyed many coastal settlements and the extinction of the moa and other food species were probably some the factors that led to sweeping changes to the culture, forming the "Te Tipunga" cultural period from 1300-1500 CE, which developed into the most well-known "Classic period" that was in place when European contact was made.

This period is characterized by finely made pounamu weapons and ornaments, elaborately carved canoes - a tradition that was later extended to and continued in elaborately carved meeting houses, and a fierce warrior culture, with fortified hillforts known as pa, frequent cannibalism and some of the largest war canoes ever built.

About 1780-90 the largest battle ever fought in New Zealand, the Battle of Hingakaka occurred, south of Ohaupo on a ridge near Lake Ngaroto. The battle was fought between about 7,000 warriors from a Taranaki-led force and a much smaller Waikato force under the leadership of Te Rauangaanga.

A force of 7,000 to 10,000 warriors, led by a Ngati Toa chief Pikauterangi, from the lower North Island invaded the Waipa District in revenge to restore honour. The Taranaki and coastal Tainui force landed to wipe out the Ngati Maniapoto and the Waikato tribes who had allied with Hauraki hapu.

Choosing to ambush the attacking force, the 1600 Waikato defenders, chose a ridge line just south of Lake Ngaroto to launch their attack. Many thousands died in the attack.

Ballara, quoting Pei Te Hurinui-Jones of Tainui, says 16,000 warriors are said to have taken part.Combatants included Waikato-Maniapoto and on the other hand Ngati Toa, Ngati Raukawa,and as far south as Taranaki and as far North as Kaipara in Northland and as far east as Bay of Plenty and the Hawke's Bay.

So many chiefs died in the battle it is known as "Fall of Parrots",as echo of the traditional mass parrot killing. The sacred carving Te Uenuku was lost in the carnage. Sources differ on the date of the battle, ranging from 1790, to "about 1803" and "about 1807".

European settlement of New Zealand occurred in relatively recent historical times. New Zealand historian Michael King in The Penguin History Of New Zealand describes the Maori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world."

Early European explorers, including Abel Tasman (who arrived in 1642) and Captain James Cook (who first visited in 1769), recorded their impressions of Maori.

From the 1780s, Maori encountered European and American sealers and whalers; some Maori crewed on the foreign ships.

A trickle of escaped convicts from Australia and deserters from visiting ships, as well as early Christian missionaries, also exposed the indigenous population to outside influences.

In the Boyd Massacre in 1809, Maori took hostage and killed 66 members of the crew and passengers in apparent revenge for the whipping of the son of a Maori chief by the captain. Several of the accounts of the survivors recounted the practice of cannibalism. This episode caused shipping companies and missionaries to be wary and significantly reduced contact between Europeans and Maori for several years.

By 1830, estimates placed the number of Europeans living among the Maori as high as 2,000. The newcomers had varying status-levels within Maori society, ranging from slaves to high-ranking advisors. Some remained little more than prisoners, while others abandoned European culture and identified as Maori.

These Europeans "gone native" became known as Pakeha Maori. Many Maori valued them as a means to the acquisition of European knowledge and technology, particularly firearms. When Pomare led a war-party against Titore in 1838, he had 131 Europeans among his warriors.

Frederick Edward Maning, an early settler, wrote two lively accounts of life in these times, which have become classics of New Zealand literature: Old New Zealand and History of the War in the North of New Zealand against the Chief Heke.

During the period from 1805 to 1840 the acquisition of muskets by tribes in close contact with European visitors upset the balance of power among Maori tribes, leading to a period of bloody inter-tribal warfare, known as the Musket Wars, which resulted in the decimation of several tribes and the driving of others from their traditional territory.

European diseases such as influenza and measles killed an unknown number of Maori: estimates vary between ten and fifty percent. Te Rangi Hiroa documents an epidemic caused by a respiratory disease that Maori called rewharewha. It "decimated" populations in the early 19th Century and "spread with extraordinary virulence throughout the North Island and even to the South..." He also says, p83: "Measles, typhoid, scarlet fever, whooping cough and almost everything, except plague and sleeping sickness, have taken their toll of Maori dead." Economic changes also took a toll; migration into unhealthy swamplands to produce and export flax led to further mortality.

With increasing Christian missionary activity, growing European settlement in the 1830s and the perceived lawlessness of Europeans in New Zealand, the British Crown, as a world power, came under pressure to intervene. Ultimately, Whitehall sent William Hobson with instructions to take possession of New Zealand. Before he arrived, Queen Victoria annexed New Zealand by royal proclamation in January 1840.

On arrival in February 1840, Hobson negotiated the Treaty of Waitangi with northern rangatira (chiefs). Other rangatira subsequently signed this treaty. In the end, 500 rangatira out of the 1500 sub-tribes of New Zealand signed the Treaty, while some influential rangatira - such as Te Wherowhero in Waikato, and Te Kani-a-Takirau from the east coast of the North Island - refused to sign. The Treaty gave Maori the rights of British subjects and guaranteed Maori property rights and tribal autonomy, in return for accepting British government or sovereignty.

Dispute continues over whether the Treaty of Waitangi ceded Maori sovereignty. Rangatira signed a Maori-language version of the Treaty that did not accurately reflect the English-language version. It appears unlikely that the Maori version of the treaty ceded sovereignty; and the Crown and the missionaries probably did not fully explain the meaning of the English version.

Despite the different understandings of the treaty, relations between Maori and Europeans during the early colonial period were largely peaceful. Many Maori groups set up substantial businesses, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas markets. Among the early European settlers who learnt the Maori language and recorded Maori mythology, George Grey, Governor of New Zealand from 1845-1855 and 1861-1868, stands out.

However, rising tensions over disputed land purchases and attempts by Maori in the Waikato to establish what some saw as a rival to the British system of royalty led to the New Zealand wars in the 1860s. These series of conflicts were fought between Crown troops and numerous Maori groups opposed to the disputed land sales. Other tribes supported or fought in support of the Crown (known as kupapa), while some were not involved at all.

Although these resulted in relatively few Maori or European deaths, the colonial government confiscated tracts of tribal land as punishment for what they called rebellion, in some cases taking land from tribes that had taken no part in the war. Some of the confiscated land was returned to both kupapa and "rebel" Maori. Several minor conflicts also arose after the wars, including the incident at Parihaka in 1881 and the Dog Tax War from 1897-98.

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 established the Native Land Court, which had the purpose of transferring Maori land from communal ownership into individual title. Maori land under individual title became available to be sold to the colonial government or to settlers in private sales.

As a result, between 1840 and 1890 Maori lost 95 percent of their land (63,000,000 of 66,000,000 acres in 1890). In total 4% of this was confiscated land, although about a quarter of this was returned. Individual Maori titleholders received considerable capital from these land sales, although disputes later arose over whether or not promised compensation in some sales was fully delivered. However, the subsequent loss of land hampered Maori participation in the growing New Zealand economy, eventually diminishing the capacity of many iwi to sustain themselves.

By the late 19th century a widespread belief existed amongst both Pakeha and Maori that the Maori population would cease to exist as a separate race or culture and become assimilated into the European population.

In 1840, New Zealand had a Maori population of about 100,000 and only about 2,000 Europeans.

By 1860 it was estimated at 50,000. The Maori population had declined to 37,520 in the 1871 census, although Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Buck) believed this figure was too low. The figure was 42,113 in the 1896 census, by which time Europeans numbered more than 700,000.

By 1936 the Maori figure was 82,326, although the sudden rise in the 1930s was probably due to the introduction of the family benefit - only payable when a birth was registered, according to Professor Poole.

The decline of the Maori population did not continue, and levels recovered. Despite a substantial level of intermarriage between the Maori and European populations, many Maori retained their cultural identity. A number of discourses developed as to the meaning of "Maori" and to who counted as Maori or not. (Maori do not form a monolithic bloc, and no one political or tribal authority can speak on behalf of all Maori.) There is no racial test to determine who is Maori or not, merely an affinity with one's Maori ancestry (regardless of how remote).

From the late 19th century, successful Maori politicians such as James Carroll, Apirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hiroa and Maui Pomare emerged. They showed skill in the arts of Pakeha politics; at one point Carroll became Acting Prime Minister. The group, known as the Young Maori Party, cut across voting-blocs in Parliament and aimed to revitalize the Maori people after the devastation of the previous century.

For them this involved assimilation - Maori adopting European ways of life such as Western medicine and education. However Ngata in particular also wished to preserve traditional Maori culture, especially the arts. Ngata acted as a major force behind the revival of arts such as kapa haka and carving. He also enacted a program of land development which helped many iwi retain and develop their land.

The government decided to exempt Maori from the conscription that applied to other citizens in World War II, but Maori volunteered in large numbers, forming the 28th or Maori Battalion, which performed creditably, notably in Crete, North Africa and Italy. Altogether 17,000 Maori took part in the war.

The urbanization of Maori proceeded apace in the second half of the 20th century. A majority of Maori people now live in cities and towns, and many have become estranged from tribal roots and customs.

Since the 1960s, Maoridom has undergone a cultural revival strongly connected with a protest movement. Government recognition of the growing political power of Maori and political activism have led to limited redress for unjust confiscation of land and for the violation of other property rights.

The Crown set up the Waitangi Tribunal, a body with the powers of a Commission of Enquiry, to investigate and make recommendations on such issues, but it cannot make binding rulings. As a result of the redress paid to many iwi (tribes), Maori now have significant interests in the fishing and forestry industries.

Tensions remain, with complaints from Maori that the settlements occur at a level of between 1 and 2.5 cents on the dollar of the value of the confiscated lands. The Government need not accept the findings of the Waitangi Tribunal, and has rejected some of them, with a most recent and widely-debated example in the New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy.

Once Were Warriors, a 1994 film adapted from a 1990 novel of the same name by Alan Duff, brought the plight of some urban Maori to a wide audience. It was the highest-grossing film in New Zealand until 2006, and received international acclaim, winning several international film prizes. While some Maori feared that viewers would consider the violent male characters an accurate portrayal of Maori men, most critics praised it as exposing the raw side of domestic violence. Some Maori opinion, particularly feminist, welcomed the debate on domestic violence that the film enabled.

In many areas of New Zealand, Maori lost its role as a living community language used by significant numbers of people in the post-war years. In tandem with calls for sovereignty and for the righting of social injustices from the 1970s onwards, many New Zealand schools now teach Maori culture and language, and pre-school kohanga reo ("language-nests") have started, which teach tamariki (young children) exclusively in Maori. These now extend right through secondary schools (kura tuarua).

In 2004 Maori Television, a government-funded channel committed to broadcasting primarily in te reo, began. Maori is an official language de jure, but English is de facto the national language.

At the 2006 Census, Maori was the second most widely-spoken language after English, with four percent of New Zealanders able to speak Maori to at least a conversational level. No official data has been gathered on fluency levels.

There are seven designated Maori seats in the Parliament of New Zealand (and Maori can and do stand in and win general roll seats), and consideration of and consultation with Maori have become routine requirements for councils and government organizations.

Debate occurs frequently as to the relevance and legitimacy of the Maori electoral roll, and the National Party announced in 2008 it would abolish the seats when all historic Treaty settlements have been resolved, which it aims to complete by 2014.

Maori on average have fewer assets than the rest of the population, and run greater risks of many negative economic and social outcomes. Over 50% of Maori live in areas in the three highest deprivation deciles, compared with 24% of the rest of the population.

Although Maori make up only 14% of the population, they make up almost 50% of the prison population. Maori have higher unemployment-rates than other cultures resident in New Zealand Maori have higher numbers of suicides than non-Maori.

"Only 47% of Maori school-leavers finish school with qualifications higher than NCEA Level One; compared to a massive 74% European; 87% Asian." Maori suffer more health problems, including higher levels of alcohol and drug abuse, smoking and obesity. Less frequent use of healthcare services mean that late diagnosis and treatment intervention lead to higher levels of morbidity and mortality in many manageable conditions, such as cervical cancer, diabetes per head of population than non-Maori.

Maori also have considerably lower life-expectancies compared to New Zealanders of European ancestry: Maori males 69.0 years vs. non-Maori males 77.2 years; Maori females 73.2 years vs. non-Maori females 81.9 years. Also, a recent study by the New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse showed that Maori women and children are more likely to experience domestic violence than any other ethnic group.

During the 1990s and 2000s, the government negotiated with Maori to provide redress for breaches by the Crown of the guarantees set out in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.

By 2006 the government had provided over NZ$900 million in settlements, much of it in the form of land deals. The largest settlement, signed on 25 June 2008 with seven Maori iwi, transferred nine large tracts of forested land to Maori control.

There is a growing Maori middle class of high achievers who see the treaty settlements as a platform for economic development.

The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Maori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct Moa species weighing from 20 to 250 kg.

Extinct Moa Rewrites New Zealand's History Science Daily - November 19, 2009

Extinct moa rewrites New Zealand's history PhysOrg - November 18, 2009

Other species, also now extinct, included a swan, a goose and the giant Haast's Eagle, which preyed upon the moa. Marine mammals, in particular seals, thronged the coasts, with coastal colonies much further north than today.

Rare white kiwi chick hatches at NZ wildlife park PhysOrg - May 26, 2011

A rare white kiwi chick hatched at a New Zealand wildlife reserve will have a protected early life - unlike wild kiwis that face nonnative predators that are slowly wiping them out, an official said.

DNA of kiwi cloaks reveals history of Maori feather trade PhysOrg - May 25, 2011

In the abstract to the paper, Lambert points out that the highly valued feathered cloaks worn by Maori tribesmen, despite being well known throughout the country, have been a bit of mystery up until now, regarding their origin. The DNA analysis lifts the veil, so to speak, and shows that the cloaks, made up of thousands of kiwi feathers, come from many parts of the multi-island country; indicating a previously unknown trade route must have been in existence.

The DNA analysis showed that most of the feathers (nearly 99%) used to construct the cloaks came from the North Island brown kiwi; a small brown flightless bird about the size of a domestic chicken. It also showed that up to 15% of the feathers used in the cloaks contained feathers from different geographic regions, which suggests previously unknown trading relationships between the various tribes in those areas. It also showed that one region in particular; the east end of the north island, had the most prolific cloak producers, as they accounted for nearly half of those studied.

One of the first known modern reports of the feathered cloaks came from Captain James Cook, who visited the islands that make up New Zealand, in 1759-60; he described them in his log as flax woven cloaks, some of which were decorated using the skin off of dogs.

Lambert suggests the DNA findings show that more movement of the various isolated tribes might have occurred after the so-called 'Musket Wars,' during the early part of the nineteenth century, gradually resulting in established trade patterns which in turn could have resulted in exchanges of the feathers used to make the cloaks by various tribes throughout the region.

Maori language commonly te reo ("the language"), is the language of the indigenous population of New Zealand, the Maori, where it has the status of an official language. Linguists classify it within the Eastern Polynesian languages as being closely related to Cook Islands Maori, Tuamotuan and Tahitian; somewhat less closely to Hawaiian and Marquesan; and more distantly to the languages of Western Polynesia, including Samoan, Tokelauan, Niuean and Tongan. According to the Maori Language Commission the number of fluent adult speakers fell to about 10,000 in 1995.

New Zealand has three official languages - Maori, English and New Zealand Sign Language. Maori gained this status with the passing of the Maori Language Act in 1987. Most government departments and agencies have bilingual names, for example, the Department of Internal Affairs Te Tari Taiwhenua, and places such as local government offices and public libraries display bilingual signs and use bilingual stationery.

New Zealand Post recognizes Maori place-names in postal addresses. Dealings with government agencies may be conducted in Maori, but in practice this almost always requires interpreters, restricting its everyday use to the limited geographical areas of high Maori fluency, and to more formal occasions, such as during public consultation.

An interpreter is on hand at sessions of Parliament, in case a Member wishes to speak in Maori. In 2009, Opposition parties held a filibuster against a local government Bill, and those who could recorded their voice votes in Maori, all faithfully interpreted.

A 1994 ruling by the Privy Council in the United Kingdom held the New Zealand Government responsible under the Treaty of Waitangi (1840) for the preservation of the language. Accordingly since March 2004, the state has funded Maori Television, broadcast partly in Maori.

On 28 March 2008 Maori Television launched its second channel, Te Reo, broadcast entirely in the Maori language, with no advertising or subtitles. In 2008 Land Information New Zealand published the first list of official place names with macrons, which indicate long vowels. Previous place name lists were derived from systems (usually mapping and GIS systems) that could not handle macrons.

According to legend, Maori came to New Zealand from the mythical Hawaiki. Current anthropological thinking places their origin in tropical Eastern Polynesia, mostly likely from the Southern Cook or Society Islands region, and that they arrived by deliberate voyages in seagoing canoes - possibly double-hulled and probably sail-rigged. These settlers probably arrived by about AD 1280. Their language and its dialects developed in isolation until the 19th century.

Since about 1800 the Maori language has had a tumultuous history. It started this period as the predominant language of New Zealand. In the 1860s it became a minority language in the shadow of the English spoken by settlers, missionaries, gold seekers, and traders from a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds. In the late 19th century the colonial governments of New Zealand and its provinces introduced an English-style school system for all New Zealanders, and from the 1880s the authorities forbade the use of Maori in schools (possibly at the request of Maori leaders, who appreciated the value to their young people of fluent English. Increasing numbers of Maori people learned English.

Until World War II (1939-1945) most Maori people spoke Maori as their first language. Worship took place in Maori; it functioned as the language of Maori homes; Maori politicians conducted political meetings in Maori; and some literature and many newspapers appeared in Maori.

As late as the 1930s, some Maori parliamentarians suffered disadvantage because Parliament's proceedings took place in English. From this period the number of speakers of Maori began to decline rapidly.

By the 1980s fewer than 20% of Maori spoke the language well enough to be classed as native speakers. Even many of those people no longer spoke Maori in the home. As a result, many Maori children failed to learn their ancestral language, and generations of non-Maori-speaking Maori emerged.

By the 1980s Maori leaders began to recognize the dangers of the loss of their language and initiated Maori-language recovery-programs such as the Kohanga Reo movement, which from 1982 immersed infants in Maori from infancy to school age. There followed in the later 1980s the founding of the Kura Kaupapa Maori, a primary-school program in Maori.

Model shows Welsh language in no danger of extinction but 'te reo Maori' is on its way out PhysOrg - January 9, 2020

A team of researchers affiliated with multiple institutions in New Zealand has developed a mathematical model that can be used to predict whether a language is at risk of disappearing. Despite the seeming worldwide popularity of languages such as English and Spanish, there are still thousands of others in use. But experts suggest between a half and one-third of them could be at risk of disappearing as more popular languages take over. In this new effort, the researchers created a mathematical model that can predict whether a given language is at risk of extinction.

Much of New Zealand's culture is derived from Maori and early British settlers. Early European art was dominated by landscapes and to a lesser extent portraits of Maori. A recent resurgence of Maori culture has seen their traditional arts of tattooing, carving, and weaving become more mainstream. Many artists now combine Maori and Western techniques to create unique art forms.

Bone Carving

Toi Moko - Mummified Maori Heads

Weaving

The country's culture has also been broadened by globalization and increased immigration from the Pacific Islands and Asia. New Zealand's diverse landscape provides many opportunities for outdoor pursuits and has provided the backdrop for a number of big budget movies.

Early Maori adapted the tropically-based east Polynesian culture in line with the challenges associated with a larger and more diverse environment, eventually developing their own distinctive culture. Social organization was largely communal with families (whanau), sub-tribes (hapu) and tribes (iwi) ruled by a chief (rangatira) whose position was subject to the community's approval. The British and Irish immigrants brought aspects of their own culture to New Zealand and also influenced Maori culture, particularly with the introduction of Christianity.

However, Maori still regard their allegiance to tribal groups as a vital part of their identity, and Maori kinship roles resemble those of other Polynesian peoples. More recently American, Australian, Asian and other European cultures have exerted influence on New Zealand. Non-Maori Polynesian cultures are also apparent, with Pasifika, the world's largest Polynesian festival, now an annual event in Auckland.

The largely rural life in early New Zealand led to the image of New Zealanders being rugged, industrious problem solvers. Modesty was expected and enforced through the "tall poppy syndrome", where high achievers received harsh criticism. At the time New Zealand was not known as an intellectual country. From the early 20th century until the late 1960s Maori culture was suppressed by the attempted assimilation of Maori into British New Zealanders In the 1960s, as higher education became more available and cities expanded urban culture began to dominate. Even though the majority of the population now lives in cities, much of New Zealand's art, literature, film and humor has rural themes.

In the mid-19th century, people discovered large numbers of moa-bones alongside human tools, with some of the bones showing evidence of butchery and cooking. Early researchers, such as Julius von Haast, a geologist, incorrectly interpreted these remains as belonging to a prehistoric Paleolithic people; later researchers, notably Percy Smith, magnified such theories into an elaborate scenario with a series of sharply-defined cultural stages which had Maori arriving in a Great Fleet in 1350 AD and replacing the so-called "moa-hunter" culture with a "classical Maori" culture based on horticulture. Current anthropological theories recognize no evidence for a pre-Maori people; the archaeological record indicates a gradual evolution in culture that varied in pace and extent according to local resources and conditions.

In the course of a few centuries, growing population led to competition for resources and an increase in warfare. The archaeological record reveals an increased frequency of fortified pa, although debate continues about the amount of conflict. Various systems arose which aimed to conserve resources; most of these, such as tapu and rahui, used religious or supernatural threats to discourage people from taking species at particular seasons or from specified areas.

Maori belief systems are encompassed and filtered through a social structuring of Tapu. Similar to the Polynesians kapu system. Tapu, Mana, Mauri, Mauri-ora, Aroha, Utu and Makutu are all entwined into the social fabric.

Warfare between tribes was common, generally over land conflicts or to restore mana. Fighting was carried out between units called hapu. Although not practiced during times of peace, Maori would sometimes eat their conquered enemies.

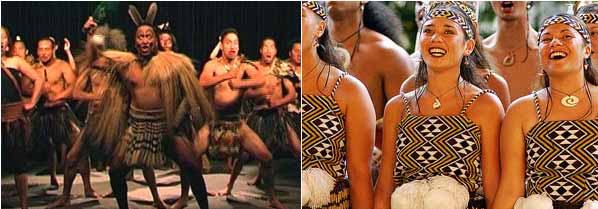

As Maori continued in geographic isolation, performing arts such as the haka developed from their Polynesian roots, as did carving and weaving. Regional dialects arose, with minor differences in vocabulary and in the pronunciation of some words. The language retains close similarities to other Eastern Polynesian languages, to the point where a Tahitian chief on Cook's first voyage in the region acted as an interpreter between Maori and the crew of the Endeavour.

Around 1500 AD a group of Maori migrated east to Rekohu (the Chatham Islands), where, by adapting to the local climate and the availability of resources, they developed a culture known as Moriori - related to but distinct from Maori culture in mainland Aotearoa. A notable feature of the Moriori culture, an emphasis on pacifism, proved disastrous when a party of invading Taranaki Maori arrived in 1835. Few of the estimated Moriori population of 2000 survived.

From the early 20th century kapa haka concert parties began touring overseas, including those led by guide Makareti (Maggie) Papakura. Since 1972 there has been a regular competition, the Te Matatini National Festival, organized by the Aotearoa Traditional Maori Performing Arts Society.

Kapa haka is taught by experts such as Ngapo (Bub) Wehi, Pita Sharples, and Tihi Puanaki, and notable kapa haka groups include Waihirere of the Gisborne area, and Te Waka Huia from Auckland. There are also kapa haka groups in schools, tertiary institutions and workplaces. Kapa haka is performed at tourist venues such as Te Puia in Whakarewarewa, Wairakei Terraces near Taupo, and Ko Tane in Willowbank Wildlife Reserve, Christchurch.

Maori "tend to be followers of Presbyterianism, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), or Maori Christian groups such as Ratana and Ringatu" but with Catholic, Anglican and Methodist groupings also prominent. There is also a growing community of Maori Muslims.

New Zealand is a country of rare seismic beauty: glacial mountains,

fast-flowing rivers, deep, clear lakes, hissing geysers and boiling mud.

There are also abundant forest reserves, long, deserted beaches and a variety of fauna, such as the kiwi, endemic to its shores. Any number of vigorous outdoor activities - hiking, skiing, rafting and, of course, that perennial favorite, bungy jumping - await the adventurous.

You can swim with dolphins, gambol with newborn lambs, whalewatch or fish for fattened trout in the many streams. The people, bound in a culture that melds European with Maori ancestry, are resourceful, helpful and overwhelmingly friendly.

Kapa haka (literally, haka team), a traditional Maori performance art form, is still popular today. It includes haka (posture dance), poi (dance accompanied by song and rhythmic movements of the poi, a light ball on a string) waiata-a-ringa (action songs) and waiata koroua (traditional chants).

From the early 20th century kapa haka concert parties began touring overseas, including those led by guide Makareti (Maggie) Papakura. Since 1972 there has been a regular competition, the Te Matatini National Festival, organised by the Aotearoa Traditional Maori Performing Arts Society.

Kapa haka is taught by experts such as Ngapo (Bub) Wehi, Pita Sharples, and Tihi Puanaki, and notable kapa haka groups include Waihirere of the Gisborne area, and Te Waka Huia from Auckland. There are also kapa haka groups in schools, tertiary institutions and workplaces. Kapa haka is performed at tourist venues such as Te Puia in Whakarewarewa, Wairakei Terraces near Taupo, and Ko Tane in Willowbank Wildlife Reserve, and Christchurch.

New Zealand music has been influenced by blues, jazz, country, rock and roll and hip hop, with many of these genres given a unique New Zealand interpretation. Maori developed traditional chants and songs from their ancient South-East Asian origins, and after centuries of isolation created a unique "monotonous" and "doleful" sound. Flutes and trumpets were used as musical instruments or as signaling devices during war or special occasions.

Early settlers brought over their ethnic music, with brass bands and choral music being popular, and musicians began touring New Zealand in the 1860s. Pipe bands became widespread during the early 20th century.[286] The New Zealand recording industry began to develop from 1940 onwards and many New Zealand musicians have obtained success in Britain and the USA. Some artists release Maori language songs and the Maori tradition-based art of kapa haka (song and dance) has made a resurgence.

Radio first arrived in New Zealand in 1922 and television in 1960, while the number of New Zealand films significantly increased during the 1970s.

In 1978 the New Zealand Film Commission started assisting local film-makers and many films attained a world audience, some receiving international acknowledgement. Deregulation in the 1980s saw a sudden increase in the numbers of radio and television stations.

New Zealand television primarily broadcasts American and British programming, along with a large number of Australian and local shows. The country's diverse scenery and compact size, plus government incentives,[289] have encouraged some producers to film big budget movies in New Zealand.

The New Zealand media industry is dominated by a small number of companies, most of which are foreign-owned, although the state retains ownership of some television and radio stations. Between 2003 and 2008, Reporters Without Borders consistently ranked New Zealand's press freedom in the top twenty.

Nowadays the music is mainly vocal. The use of instruments became neglected under influence of christianity, but today there is a strong revival movement. Originally Maori people only used aerophones and idiophones. Of course recently in contemporary commercial music the guitar and ukelele made their appearance too.

The vocal music can be divided in two categories: the recitatives and the songs. The recitatives have no fixed pitch organization and the tempo is much higher than the song's tempo.

Maori music, like all ethnic music, has changed rapidly in time under the influence of western culture. Western ethno-musicologists have a mainly negative attitude towards these changes. And many times we can agree, because the traditional culture disappears under commercialization along western standards. But in the case of the Maori we would prefer to be more nuanced, because we see next to the commercialization a strong revival of the traditional Maori music too.

Another form of traditional music are Songs and the Sung Poetry, also called Nga Moteatea, which often consist mainly of laments, but sometimes also consist of love songs and lullabies. Traditionally, sung poetry of this form was accompanied by a koauau flute.

Traditional songs comprise the following forms: Poi, which are songs accompanied by a form of dance in which women hit their body rhythmically with one or two mainly cotton balls attached to the end of a string. Oriori, which are songs composed to teach children of high rank about their special descent and history. Pao are songs originating out of a kind of instant-composing: the composer sings the first couplet and is then repeated by the chorus, and so on. These are songs of local interest. They can be funny or serious.Waiata is the most common category of Maori songs and comprise laments about different topics. Traditionally, waiata are sung in groups and in unisono.

Waiata tangi are laments for the dead. The word 'tangi' means 'weeping'. This form is mainly composed by women. During burial ceremonies, women were expected to show signs of deep grief, for example, by wounding their faces with sharp stones. Sometimes, these waiata were very personal, telling about the composer's emotions and feelings towards the dead. When composed by men, the waiata tangi can also instruct us about the warrior qualities of the dead person. They can also, for example, allude to most of the calamities that can befall mankind.

Finally, waiata ahore are love songs, and waiata whaiaaipo are songs for the beloved one. They are often still laments and tell us about all the misery that a love affair can provoke.

The traditional vocal music can be divided in two categories: the recitatives and the songs. The recitatives have no fixed pitch organization and the tempo is much higher than the song's tempo. Among the recitatives is a welcome ceremony known as Powhiri. This welcome ceremony is a mixed form. Men shout fiercely, whilst women sing in a melodic way. The Powhiri often starts with the men standing in front of the women. The men make clear they are ready for a battle by shouting, menacing with their weapons and grimacing. After a while, the women gently come to the front, singing and carrying green leaves. The men kneeled down on one knee and put their weapons on the floor. Most of the time a Powhiri ends with a haka (men song) without weapons.

Powhiri -- This welcome ceremony is a mixed form. Men shout fiercly, whilst women sing in a melodic way. The Powhiri which was specially executed for us in Christchurch during our New Zealand concert tour started with the men standing in front of the women. They made clear they were ready for a battle by shouting, menacing with their weapons and grimacing. After a while the women came to the front, singing and carrying green leaves they moved gently. The men kneeled down on one knee and put their weapons on the floor. Most of the times a powhiri ends with a haka (men song) without weapons.

Haka are shouted speeches by men, combined with a fierce dance. Haka Taparahi are performed without weapons and they can give expression to different emotions depending on the situation for which they are performed. Haka Peruperu are performed with weapons and associated with war dances.

Ngeri -- used to annihilate any form of tapu.

Karakia are quick incantations and spells.They are used during daily life by both adults and children, but also during rituals. The ritual karakia is difficult and dangerous to execute, because a mistake during the performance will attract bad luck, illness and even the death of the reciter. For very important karakia two priest reciters are needed in order to alternate the breathing pauze, because even the slightest moment of silence could result into disaster.

Paatere are mainly performed in group and composed by women in answer to gossip. The texts of paatere consist merely out of summing up of the kinship connections of the author.

Kaioraora are like paatere answers to gossip but with a rude, offensive text.

There are songs and sung poetry called 'Nga Moteatea'.

Nguru

This small instrument (8 to 10 cm) is curved at one end, because originally this flute was made out of a whale tooth. It can also be made out of wood, stone, clay. It has one open end like the koauau and one small opening at the curved end. It has 2 to 4 fingerholes.

New Zealand literature is essentially literature in English that is either written by New Zealanders, or migrants, dealing with New Zealand themes or places and is primarily a 20th Century creation. New Zealand literature is almost exclusively literature in the English language and as such a sub-type of English literature.

The Maori were a pre-literate stone-aged culture until contact with Europeans in the early 19th Century. New Zealand acknowledges the presence of its indigenous Maori and the special place they have in New Zealand culture. Oratory and recitation of quasi historical / hagiographical ancestral blood lines has a special place in Maori culture, eurocentric notions of 'literature' may fail to describe the Maori cultural forms in the oral tradition.

In the early nineteenth century Christian missionaries developed written forms of Polynesian languages to assist with their evangelical work. The oral tradition of story telling and folklore has survived and the early missionaries collected folk tales. In the pre-colonial period there was no literature, after European contact and the introduction of literacy there were Maori language publications.

No literary works in Maori have been translated and become widely read. The Maori language has survived to the present day and although not widely spoken is used in as medium of instruction in education in a small number of schools. As far as Maori literature can be said to exist, it is principally literature in English dealing with Maori themes.

New Zealand poetry, like all poetry, is influenced by time and place and has been through a number of changes. Poetry has been part of New Zealand culture since before European settlement in the form of Maori sung poems or waiata. The first colonial Pakeha poetry was also predominantly sung poetry. Initially colonial poetry had a preoccupation with British themes. New Zealand poetry developed a strong local voice from the 1950s, and has now become a "polyphony" of traditionally marginalized voices.

Sport in New Zealand -- Most of the major sporting codes played in New Zealand have English origins. Golf, netball, tennis and cricket are the four top participatory sports, soccer is the most popular among young people and rugby union attracts the most spectators.

Victorious rugby tours to Australia and the United Kingdom in the late 1880s and the early 1900s played an early role in instilling a national identity, although the sport's influence has since declined. Horse racing was also a popular spectator sport and became part of the "Rugby, Racing and Beer" culture during the 1960s. Maori participation in European sports was particularly evident in rugby and the country's team performs a haka (traditional Maori challenge) before international matches.

New Zealand has competitive international teams in rugby union, netball, cricket, rugby league, and softball and has traditionally done well in triathlons, rowing, yachting and cycling. The country has performed well on a medals-to-population ratio at Olympic Games and Commonwealth Games.

New Zealand is known for its extreme sports, adventure tourism and strong mountaineering tradition.[300] Other outdoor pursuits such as cycling, fishing, swimming, running, tramping, canoeing, hunting, snowsports and surfing are also popular. The Polynesian sport of waka ama racing has increased in popularity and is now an international sport involving teams from all over the Pacific.

Maori religion is the religious beliefs and practice of the Maori, the Polynesian indigenous people of New Zealand. Traditional Maori religion, that is, the pre-European belief system of the Maori, was little modified from that of their tropical Eastern Polynesian homeland (Hawaiki Nui), conceiving of everything, including natural elements and all living things as connected by common descent through whakapapa or genealogy.

Accordingly, all things were thought of as possessing a life force or mauri. As an illustration of this concept of connectedness through genealogy, consider a few of the major personifications of pre-contact times: Tangaroa was the personification of the ocean and the ancestor or origin of all fish; Tane was the personification of the forest and the origin of all birds; and Rongo was the personification of peaceful activities and agriculture and the ancestor of cultivated plants. (According to some, the supreme personification of the Maori was Io; however this idea is controversial.)

Maori "tend to be followers of Presbyterianism, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), or Maori Christian groups such as Ratana and Ringatu", but with Catholic, Anglican and Methodist groupings also prominent. There is also a growing community of Maori Muslims.

Maori Mythology and Maori Traditions are the two major categories into which the legends of the Maori of New Zealand may usefully be divided. The rituals, beliefs, and the world view of Maori society were ultimately based on an elaborate mythology that had been inherited from a Polynesian homeland and adapted and developed in the new setting.

Little of the extensive body of Maori mythology and tradition was recorded in the early years of European contact. The missionaries had the best opportunity to get the information, but failed to do so at first, in part because their knowledge of the language was imperfect. Most of the missionaries who did master the language were unsympathetic to Maori beliefs, regarding them as 'puerile beliefs', or even 'works of the devil'.

Exceptions to this general rule were J. F. Wohlers of the South Island, Richard Taylor, who worked in the Taranaki and Wanganui River areas, and William Colenso who lived at the Bay of Islands and also in Hawke's Bay. "The writings of these men are among our best sources for the legends of the areas in which they worked".

Tiki are anthropomorphic ornaments representing spiritual beings. Many times they have some kind of deformation, like only 3 fingers and they can be both positive and negative towards mankind. Much of the Maori religion remains intact and many rituals associated with traditional visual arts and traditional music are still carried out with strong ties between songs and magic still remaining.

The Maori view of creation in which all nature was seen as a great kinship tracing its origins back to a single pair, the Sky Father and the Earth Mother, was a conception which they brought with them when they came from Central Polynesia about 1,000 A.D. Furthermore, this belief in a primal pair, as well as the metaphysical idea of an original Void or Darkness, seems to be part of the stock of ideas which the ancestors of the Polynesians brought with them from the west, from the Asian mainland, and which they carried with them as they dispersed into marginal Polynesia. The resultant shift in names and attributes, and the elaboration of themes which occurred throughout the area certainly cannot obscure this underlying unity of ideas.

In the Chatam Islands 200 miles east of the NZ mainland at Whangaroa (Port Hutt). E.J. Prenderville tells of a haunted cottage. It was used by fishermen working for the trawler South Seas. Legend has it that many years ago, the then occupier of the cottage, after drinking a considerable amount of squareface gin, bent forward to get an ember for his pipe and his breath caught fire. From that time, the tormented spirit has caused many a short stay at that cottage.

Many stories have been told of the Grey Lady of the old Dunedin Hospital. It's thought she was a young mother, whose baby was taken into care. After she had given birth the young woman sank into a deep depression and subsequently died. Her pitiful ghost wandered between Ward one and Victoria ward going by the stairs to Jubilee ward. She was thought to be looking for her baby. Many nurses reported seeing the shadowy ghostly apparition late in the evenings.

Wellington Opera House was built early this century and so the story goes that it too has it's own ghost. One with a few troubled memories. Albert Liddy the theatres architect was so unhappy that he committed suicide in his design office at the back of the theatre. It is said that accidents befall anyone who dares to criticize his theatre. A former manager claims there were three such accidents during his time as manager. All in the same place. The troubled apparition has been still for some time now, perhaps he has found peace, or perhaps no one dares to criticize his theatre.

Macki Ruka was an international speaker and healer, chosen at age three to be initiated into the highest teachings of the celestial and earthly realms. He was chosen by the United Nations as one of seven elders to take ancient prophecies to the world. Macki has traveled around the world five times in his journey, meeting with the Pope, the Dali Lama, Mother Theresa, and other world spiritual leaders.