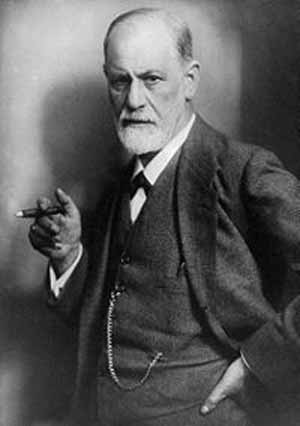

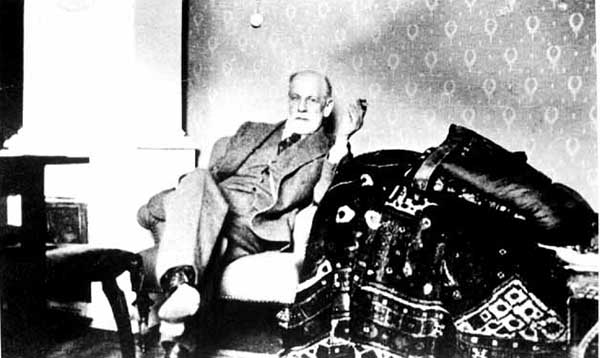

Sigmund Freud (May 6, 1856 - September 23, 1939) was an Austrian neurologist who founded the psychoanalytic school of psychiatry. Freud is best known for his theories of the unconscious mind and the defense mechanism of repression, and for creating the clinical practice of psychoanalysis for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient, technically referred to as an "analysand", and a psychoanalyst. Freud redefined sexual desire as the primary motivational energy of human life, developed therapeutic techniques such as the use of free association, created the theory of transference in the therapeutic relationship, and interpreted dreams as sources of insight into unconscious desires. He was an early neurological researcher into cerebral palsy, and a prolific essayist, drawing on psychoanalysis to contribute to the history, interpretation and critique of culture.

While many of Freud's ideas have fallen out of favor or been modified by other analysts, and modern advances in the field of psychology have shown flaws in some of his theories, his work remains influential in clinical approaches, and in the humanities and social sciences. He is considered one of the most prominent thinkers of the first half of the 20th century, in terms of originality and intellectual influence.

Freud has been influential in two related but distinct ways: he simultaneously developed a theory of the human mind's organization and internal operations and a theory that human behavior both conditions and results from how the mind is organized. This led him to favor certain clinical techniques for trying to help cure mental illness. He theorized that personality is developed by a person's childhood experiences. In his philosophical writings he advocated an atheistic world view; he was eulogized as "'the atheist's touchstone' for the 20th century.

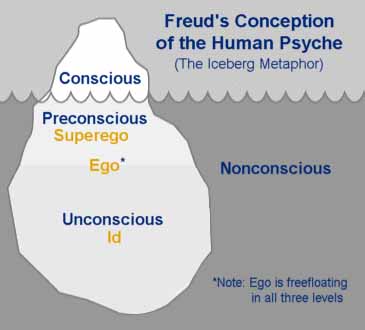

He articulated and refined the concepts of the unconscious, of infantile sexuality, of repression, and proposed a tri-partite account of the mind's structure, all as part of a radically new conceptual and therapeutic frame of reference for the understanding of human psychological development and the treatment of abnormal mental conditions.

Notwithstanding the multiple manifestations of psychoanalysis as it exists today, it can in almost all fundamental respects be traced directly back to Freud's original work. Further, Freud's innovative treatment of human actions, dreams, and indeed of cultural artifacts as invariably possessing implicit symbolic significance has proven to be extraordinarily fecund, and has had massive implications for a wide variety of fields, including anthropology, semiotics, and artistic creativity and appreciation in addition to psychology. However, Freud's most important and frequently re-iterated claim, that with psychoanalysis he had invented a new science of the mind, remains the subject of much critical debate and controversy.

Freud was born in Frieberg, Moravia in 1856, but when he was four years old his family moved to Vienna, where Freud was to live and work until the last year of his life. In 1937 the Nazis annexed Austria, and Freud, who was Jewish, was allowed to leave for England. For these reasons, it was above all with the city of Vienna that Freud's name was destined to be deeply associated for posterity, founding as he did what was to become known as the 'first Viennese school' of psychoanalysis, from which, it is fair to say, psychoanalysis as a movement and all subsequent developments in this field flowed.

The scope of Freud's interests, and of his professional training, was very broad - he always considered himself first and foremost a scientist, endeavoring to extend the compass of human knowledge, and to this end (rather than to the practice of medicine) he enrolled at the medical school at the University of Vienna in 1873.

He concentrated initially on biology, doing research in physiology for six years under the great German scientist Ernst BrŮcke, who was director of the Physiology Laboratory at the University, thereafter specialising in neurology. He received his medical degree in 1881, and having become engaged to be married in 1882, he rather reluctantly took up more secure and financially rewarding work as a doctor at Vienna General Hospital. Shortly after his marriage in 1886 - which was extremely happy, and gave Freud six children, the youngest of whom, Anna, was herself to become a distinguished psychoanalyst - Freud set up a private practice in the treatment of psychological disorders, which gave him much of the clinical material on which he based his theories and his pioneering techniques.

In 1885-86 Freud spent the greater part of a year in Paris, where he was deeply impressed by the work of the French neurologist Jean Charcot, who was at that time using hypnotism to treat hysteria and other abnormal mental conditions. When he returned to Vienna, Freud experimented with hypnosis, but found that its beneficial effects did not last. At this point he decided to adopt instead a method suggested by the work of an older Viennese colleague and friend, Josef Breuer, who had discovered that when he encouraged a hysterical patient to talk uninhibitedly about the earliest occurrences of the symptoms, the latter sometimes gradually abated.

Working with Breuer, Freud formulated and developed the idea that many neuroses (phobias, hysterical paralyses and pains, some forms of paranoia, etc.) had their origins in deeply traumatic experiences which had occurred in the past life of the patient but which were now forgotten, hidden from consciousness; the treatment was to enable the patient to recall the experience to consciousness, to confront it in a deep way both intellectually and emotionally, and in thus discharging it, to remove the underlying psychological causes of the neurotic symptoms. This technique, and the theory from which it is derived, was given its classical expression in Studies in Hysteria, jointly published by Freud and Breuer in 1895.

Shortly thereafter, however, Breuer, found that he could not agree with what he regarded as the excessive emphasis which Freud placed upon the sexual origins and content of neuroses, and the two parted company, with Freud continuing to work alone to develop and refine the theory and practice of psychoanalysis.

In 1900, after a protracted period of self-analysis, he published The Interpretation of Dreams, which is generally regarded as his greatest work, and this was followed in 1901 by The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, and in 1905 by Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.

Freud's psychoanalytic theory was initially not well received - when its existence was acknowledged at all it was usually by people who were, as Breuer had foreseen, scandalized by the emphasis placed on sexuality by Freud - and it was not until 1908, when the first International Psychoanalytical Congress was held at Salzburg, that Freud's importance began to be generally recognized.

This was greatly facilitated in 1909, when he was invited to give a course of lectures in the United States, which were to form the basis of his 1916 book Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. From this point on Freud's reputation and fame grew enormously, and he continued to write prolifically until his death, producing in all more than twenty volumes of theoretical works and clinical studies. He was also not adverse to critically revising his views, or to making fundamental alterations to his most basic principles when he considered that the scientific evidence demanded it - this was most clearly evidenced by his advancement of a completely new tripartite (id, ego, and super-ego) model of the mind in his 1923 work The Ego and the Id.

He was initially greatly heartened by attracting followers of the intellectual calibre of Adler and Jung, and was correspondingly disappointed personally when they both went on to found rival schools of psychoanalysis - thus giving rise to the first two of many schisms in the movement - but he knew that such disagreement over basic principles had been part of the early development of every new science. After a life of remarkable vigor and creative productivity, he died of cancer while exiled in England in 1939.

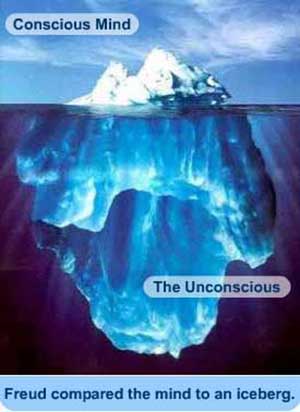

Perhaps the most significant contribution Freud made to Western thought were his arguments concerning the importance of the unconscious mind in understanding conscious thought and behavior. However, as psychologist Jacques Van Rillaer pointed out, "contrary to what most people believe, the unconscious was not discovered by Freud. In 1890, when psychoanalysis was still unheard of, William James, in Principles of Psychology his monumental treatise on psychology, examined the way Schopenhauer, von Hartmann, Janet, Binet and others had used the term 'unconscious' and 'subconscious'".

Boris Sidis, a Russian Jew who emigrated to the United States of America in 1887, and studied under William James, wrote The Psychology of Suggestion: A Research into the Subconscious Nature of Man and Society in 1898, followed by ten or more works over the next twenty five years on similar topics to the works of Freud. Historian of psychology Mark Altschule concluded, "It is difficult - or perhaps impossible - to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognize unconscious cerebration as not only real but of the highest importance." Freud's advance was not to uncover the unconscious but to devise a method for systematically studying it.

Freud called dreams the "royal road to the unconscious". This meant that dreams illustrate the "logic" of the unconscious mind. Freud developed his first topology of the psyche in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) in which he proposed that the unconscious exists and described a method for gaining access to it. The preconscious was described as a layer between conscious and unconscious thought; its contents could be accessed with a little effort.

One key factor in the operation of the unconscious is "repression". Freud believed that many people "repress" painful memories deep into their unconscious mind. Although Freud later attempted to find patterns of repression among his patients in order to derive a general model of the mind, he also observed that repression varies among individual patients. Freud also argued that the act of repression did not take place within a person's consciousness. Thus, people are unaware of the fact that they have buried memories or traumatic experiences.

Later, Freud distinguished between three concepts of the unconscious: the descriptive unconscious, the dynamic unconscious, and the system unconscious. The descriptive unconscious referred to all those features of mental life of which people are not subjectively aware. The dynamic unconscious, a more specific construct, referred to mental processes and contents that are defensively removed from consciousness as a result of conflicting attitudes. The system unconscious denoted the idea that when mental processes are repressed, they become organized by principles different from those of the conscious mind, such as condensation and displacement.

Eventually, Freud abandoned the idea of the system unconscious, replacing it with the concept of the ego, super-ego, and id. Throughout his career, however, he retained the descriptive and dynamic conceptions of the unconscious.

This takes us to my concept of Consciousness Frozen in Time

Id, ego and super-ego are the three parts of the psychic apparatus defined in Sigmund Freud's structural model of the psyche; they are the three theoretical constructs in terms of whose activity and interaction mental life is described. According to this model of the psyche, the id is the set of uncoordinated instinctual trends; the super-ego plays the critical and moralizing role; and the ego is the organized, realistic part that mediates between the desires of the id and the super-ego. The super-ego can stop you from doing certain things that your id may want you to do.

Even though the model is structural and makes reference to an apparatus, the id, ego and super-ego are functions of the mind rather than parts of the brain and do not correspond one-to-one with actual somatic structures of the kind dealt with by neuroscience.

The concepts themselves arose at a late stage in the development of Freud's thought: the "structural model" (which succeeded his "economic model" and "topographical model") was first discussed in his 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle and was formalized and elaborated upon three years later in his The Ego and the Id. Freud's proposal was influenced by the ambiguity of the term "unconscious" and its many conflicting uses.

The Id is the unorganized part of the personality structure that contains a human's basic, instinctual drives. Id is the only component of personality that is present from birth. It is the source of our bodily needs, wants, desires, and impulses, particularly our sexual and aggressive drives. The id contains the libido, which is the primary source of instinctual force that is unresponsive to the demands of reality. The id acts according to the "pleasure principle"--the psychic force that motivates the tendency to seek immediate gratification of any impulse-- defined as, seeking to avoid pain or unpleasure (not 'displeasure') aroused by increases in instinctual tension. If the mind was solely guided by the id, individuals would find it difficult to wait patiently at a restaurant, while feeling hungry, and would most likely grab food from neighbouring tables.

According to Freud the id is unconscious by definition:

The Ego acts according to the reality principle; i.e. it seeks to please the idŐs drive in realistic ways that will benefit in the long term rather than bring grief. At the same time, Freud concedes that as the ego "attempts to mediate between id and reality, it is often obliged to cloak the Ucs.

Unconscious commands of the id with its own Pcs. Preconscious rationalizations, to conceal the id's conflicts with reality, to profess ... to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding."The reality principle that operates the ego is a regulating mechanism that enables the individual to delay gratifying immediate needs and function effectively in the real world. An example would be to resist the urge to grab other people's belongings and buy them instead.

The ego is the organized part of the personality structure that includes defensive, perceptual, intellectual-cognitive, and executive functions. Conscious awareness resides in the ego, although not all of the operations of the ego are conscious. Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean a sense of self, but later revised it to mean a set of psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory.

The ego separates out what is real. It helps us to organize our thoughts and make sense of them and the world around us. "The ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions in its relation to the id it is like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse; with this difference, that the rider tries to do so with his own strength, while the ego uses borrowed forces."

Still worse, "it serves three severe masters the external world, the super-ego and the id." Its task is to find a balance between primitive drives and reality while satisfying the id and super-ego. Its main concern is with the individual's safety and allows some of the id's desires to be expressed, but only when consequences of these actions are marginal. "Thus the ego, driven by the id, confined by the super-ego, repulsed by reality, struggles in bringing about harmony among the forces and influences working in and upon it," and readily "breaks out in anxiety - realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the super-ego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id."

It has to do its best to suit all three, thus is constantly feeling hemmed by the danger of causing discontent on two other sides. It is said, however, that the ego seems to be more loyal to the id, preferring to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the super-ego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority.

To overcome this the ego employs defense mechanisms. The defense mechanisms are not done so directly or consciously. They lessen the tension by covering up our impulses that are threatening.[24] Ego defense mechanisms are often used by the ego when id behavior conflicts with reality and either society's morals, norms, and taboos or the individual's expectations as a result of the internalization of these morals, norms, and their taboos.

Denial, displacement, intellectualization, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalization, reaction formation, regression, repression, and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. However, his daughter Anna Freud clarified and identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealization, identification, introjection, inversion, somatisation, splitting, and substitution.

The superego reflects the internalization of cultural rules, mainly taught by parents applying their guidance and influence. Freud developed his concept of the super-ego from an earlier combination of the ego ideal and the special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured what we call our conscience. For him the installation of the super-ego can be described as a successful instance of identification with the parental agency, while as development proceeds the super-ego also takes on the influence of those who have stepped into the place of parents - educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models.

The super-ego aims for perfection. It forms the organized part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency (commonly called "conscience") that criticizes and prohibits his or her drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions.

The Super-ego can be thought of as a type of conscience that punishes misbehavior with feelings of guilt. For example, for having extra-marital affairs." Taken in this sense, the super-ego is the precedent for the conceptualization of the inner critic as it appears in contemporary therapies such as IFS and Voice Dialogue.

The super-ego works in contradiction to the id. The super-ego strives to act in a socially appropriate manner, whereas the id just wants instant self-gratification. The super-ego controls our sense of right and wrong and guilt. It helps us fit into society by getting us to act in socially acceptable ways.

The super-ego's demands often oppose the IdŐs, so the ego sometimes has a hard time in reconciling the two. The super-ego's demands often oppose the idŐs, so the ego sometimes has a hard time in reconciling the two.

Freud's theory implies that the super-ego is a symbolic internalization of the father figure and cultural regulations. The super-ego tends to stand in opposition to the desires of the id because of their conflicting objectives, and its aggressiveness towards the ego. The super-ego acts as the conscience, maintaining our sense of morality and proscription from taboos. The super-ego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the Oedipus complex. Its formation takes place during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex and is formed by an identification with and internalization of the father figure after the little boy cannot successfully hold the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration.

Freud hoped to prove that his model was universally valid and thus turned to ancient mythology and contemporary ethnography for comparative material. Freud named his new theory the Oedipus complex after the famous Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. "I found in myself a constant love for my mother, and jealousy of my father. I now consider this to be a universal event in childhood," Freud said.

Freud sought to anchor this pattern of development in the dynamics of the mind. Each stage is a progression into adult sexual maturity, characterized by a strong ego and the ability to delay gratification (cf. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality). He used the Oedipus conflict to point out how much he believed that people desire incest and must repress that desire. The Oedipus conflict was described as a state of psychosexual development and awareness. He also turned to anthropological studies of totemism and argued that totemism reflected a ritualized enactment of a tribal Oedipal conflict.

Freud originally posited childhood sexual abuse as a general explanation for the origin of neuroses, but he abandoned this so-called "seduction theory" as insufficiently explanatory. He noted finding many cases in which apparent memories of childhood sexual abuse were based more on imagination than on real events. During the late 1890s Freud, who never abandoned his belief in the sexual etiology of neuroses, began to emphasize fantasies built around the Oedipus complex as the primary cause of hysteria and other neurotic symptoms. Despite this change in his explanatory model, Freud always recognized that some neurotics had in fact been sexually abused by their fathers. He explicitly discussed several patients whom he knew to have been abused.

Freud also believed that the libido developed in individuals by changing its object, a process codified by the concept of sublimation. He argued that humans are born "polymorphously perverse", meaning that any number of objects could be a source of pleasure. He further argued that, as humans develop, they become fixated on different and specific objects through their stages of development - first in the oral stage (exemplified by an infant's pleasure in nursing), then in the anal stage (exemplified by a toddler's pleasure in evacuating his or her bowels), then in the phallic stage.

Freud argued that children then passed through a stage in which they fixated on the mother as a sexual object (known as the Oedipus Complex) but that the child eventually overcame and repressed this desire because of its taboo nature. (The term 'Electra complex' is sometimes used to refer to such a fixation on the father, although Freud did not advocate its use.) The repressive or dormant latency stage of psychosexual development preceded the sexually mature genital stage of psychosexual development.

Freud's views have sometimes been called phallocentric. This is because, for Freud, the unconscious desires the phallus (penis). Males are afraid of losing their masculinity, symbolized by the phallus, to another male. Females always desire to have a phallus - an unfulfillable desire. Thus boys resent their fathers (fear of castration) and girls desire theirs.

Freud believed that humans were driven by two conflicting central desires: the life drive (libido/Eros) (survival, propagation, hunger, thirst, and sex) and the death drive (Thanatos). Freud's description of Cathexis, whose energy is known as libido, included all creative, life-producing drives. The death drive (or death instinct), whose energy is known as anticathexis, represented an urge inherent in all living things to return to a state of calm: in other words, an inorganic or dead state.

Freud recognized the death drive only in his later years and developed his theory of it in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Freud approached the paradox between the life drives and the death drives by defining pleasure and unpleasure. According to Freud, unpleasure refers to stimulus that the body receives. (For example, excessive friction on the skin's surface produces a burning sensation; or, the bombardment of visual stimuli amidst rush hour traffic produces anxiety.)

Conversely, pleasure is a result of a decrease in stimuli (for example, a calm environment the body enters after having been subjected to a hectic environment). If pleasure increases as stimuli decreases, then the ultimate experience of pleasure for Freud would be zero stimulus, or death.

Given this proposition, Freud acknowledged the tendency for the unconscious to repeat unpleasurable experiences in order to desensitize, or deaden, the body. This compulsion to repeat unpleasurable experiences explains why traumatic nightmares occur in dreams, as nightmares seem to contradict Freud's earlier conception of dreams purely as a site of pleasure, fantasy, and desire. On the one hand, the life drives promote survival by avoiding extreme unpleasure and any threat to life. On the other hand, the death drive functions simultaneously toward extreme pleasure, which leads to death. Freud addressed the conceptual dualities of pleasure and unpleasure, as well as sex/life and death, in his discussions on masochism and sadomasochism. The tension between life drive and death drive represented a revolution in his manner of thinking.

These ideas resemble aspects of the philosophies of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. Schopenhauer's pessimistic philosophy, expounded in The World as Will and Representation, describes a renunciation of the will to live that corresponds on many levels with Freud's Death Drive. Similarly, the life drive clearly parallels much of Nietzsche's concept of the Dionysian in The Birth of Tragedy. However, Freud denied having been acquainted with their writings before he formulated the groundwork of his own ideas.

Freud's account of the unconscious, and the psychoanalytic therapy associated with it, is best illustrated by his famous tripartite model of the structure of the mind or personality (although, as we have seen, he did not formulate this until 1923), which has many points of similarity with the account of the mind offered by Plato over 2,000 years earlier.

The theory is termed 'tripartite' simply because, again like Plato, Freud distinguished three structural elements within the mind, which he called id, ego, and super-ego. The id is that part of the mind in which are situated the instinctual sexual drives which require satisfaction; the super-ego is that part which contains the 'conscience', viz. socially-acquired control mechanisms (usually imparted in the first instance by the parents) which have been internalized; while the ego is the conscious self created by the dynamic tensions and interactions between the id and the super-ego, which has the task of reconciling their conflicting demands with the requirements of external reality.

It is in this sense that the mind is to be understood as a dynamic energy-system. All objects of consciousness reside in the ego, the contents of the id belong permanently to the unconscious mind, while the super-ego is an unconscious screening-mechanism which seeks to limit the blind pleasure-seeking drives of the id by the imposition of restrictive rules.

There is some debate as to how literally Freud intended this model to be taken (he appears to have taken it extremely literally himself), but it is important to note that what is being offered here is indeed a theoretical model, rather than a description of an observable object, which functions as a frame of reference to explain the link between early childhood experience and the mature adult (normal or dysfunctional) personality.

Freud also followed Plato in his account of the nature of mental health or psychological well-being, which he saw as the establishment of a harmonious relationship between the three elements which constitute the mind. If the external world offers no scope for the satisfaction of the id's pleasure drives, or, more commonly, if the satisfaction of some or all of these drives would indeed transgress the moral sanctions laid down by the super-ego, then an inner conflict occurs in the mind between its constituent parts or elements - failure to resolve this can lead to later neurosis.

A key concept introduced here by Freud is that the mind possesses a number of 'defense mechanisms' to attempt to prevent conflicts from becoming too acute, such as repression (pushing conflicts back into the unconscious), sublimation (channelling the sexual drives into the achievement socially acceptable goals, in art, science, poetry, etc.), fixation (the failure to progress beyond one of the developmental stages), and regression (a return to the behavior characteristic of one of the stages).

Of these, repression is the most important, and Freud's account of this is as follows: when a person experiences an instinctual impulse to behave in a manner which the super-ego deems to be reprehensible (e.g. a strong erotic impulse on the part of the child towards the parent of the opposite sex), then it is possible for the mind push it away, to repress it into the unconscious.

Repression is thus one of the central defense mechanisms by which the ego seeks to avoid internal conflict and pain, and to reconcile reality with the demands of both id and super-ego. As such it is completely normal and an integral part of the developmental process through which every child must pass on the way to adulthood.

However, the repressed instinctual drive, as an energy-form, is not and cannot be destroyed when it is repressed - it continues to exist intact in the unconscious, from where it exerts a determining force upon the conscious mind, and can give rise to the dysfunctional behavior characteristic of neuroses.

This is one reason why dreams and slips of the tongue possess such a strong symbolic significance for Freud, and why their analysis became such a key part of his treatment - they represent instances in which the vigilance of the super-ego is relaxed, and when the repressed drives are accordingly able to present themselves to the conscious mind in a transmuted form.

The difference between 'normal' repression and the kind of repression which results in neurotic illness is one of degree, not of kind - the compulsive behavior of the neurotic is itself a behavioral manifestation of an instinctual drive repressed in childhood. Such behavioral symptoms are highly irrational (and may even be perceived as such by the neurotic), but are completely beyond the control of the subject, because they are driven by the now unconscious repressed impulse.

Freud positioned the key repressions, for both the normal individual and the neurotic, in the first five years of childhood, and, of course, held them to be essentially sexual in nature - as we have seen, repressions which disrupt the process of infantile sexual development in particular, he held, lead to a strong tendency to later neurosis in adult life.

The task of psychoanalysis as a therapy is to find the repressions which are causing the neurotic symptoms by delving into the unconscious mind of the subject, and by bringing them to the forefront of consciousness, to allow the ego to confront them directly and thus to discharge them.

Freud's account of the sexual genesis and nature of neuroses led him naturally to develop a clinical treatment for treating such disorders. This has become so influential today that when people speak of 'psychoanalysis' they frequently refer exclusively to the clinical treatment; however, the term properly designates both the clinical treatment and the theory which underlies it.

The aim of the method may be stated simply in general terms - to re-establish a harmonious relationship between the three elements which constitute the mind by excavating and resolving unconscious repressed conflicts.

The actual method of treatment pioneered by Freud grew out of Breuer's earlier discovery, mentioned above, that when a hysterical patient was encouraged to talk freely about the earliest occurrences of her symptoms and fantasies, the symptoms began to abate, and were eliminated entirely she was induced to remember the initial trauma which occasioned them.

Turning away from his early attempts to explore the unconscious through hypnosis, Freud further developed this 'talking cure', acting on the assumption that the repressed conflicts were buried in the deepest recesses of the unconscious mind.

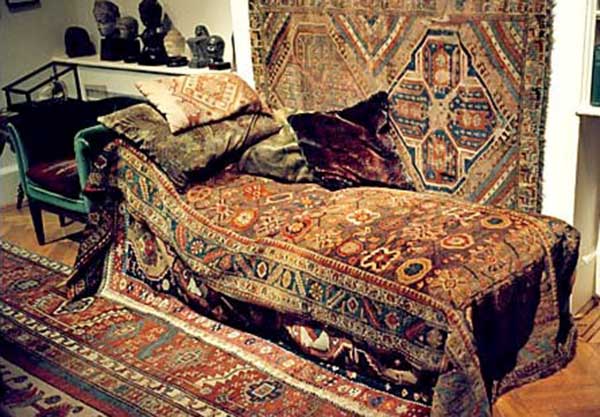

Accordingly, he got his patients to relax in a position in which they were deprived of strong sensory stimulation, even of keen awareness of the presence of the analyst - hence the famous use of the couch - with the analyst virtually silent and out of sight and then encouraged them to speak freely and uninhibitedly, preferably without forethought, in the belief that he could thereby discern the unconscious forces lying behind what was said.

This is the method of 'free-association', the rationale for which is similar to that involved in the analysis of dreams - in both cases the super-ego is to some degree disarmed, its efficiency as a screening mechanism is moderated, and material is allowed to filter through to the conscious ego which would otherwise be completely repressed. The process is necessarily a difficult and protracted one, and it is therefore one of the primary tasks of the analyst to help the patient to recognize, and to overcome, his own natural resistances, which may exhibit themselves as hostility towards the analyst.

However, Freud always took the occurrence of resistance as a sign that he was on the right track in his assessment of the underlying unconscious causes of the patient's condition. The patient's dreams are of particular interest, for reasons which we have already partly seen. Taking it that the super-ego functioned less effectively in sleep, as in free association, Freud made a distinction between the manifest content of a dream (what the dream appeared to be about on the surface) and its latent content (the unconscious, repressed desires or wishes which are its real object).

The correct interpretation of the patient's dreams, slips of tongue, free-associations, and responses to carefully selected questions leads the analyst to a point where he can locate the unconscious repressions producing the neurotic symptoms, invariably in terms of the patient's passage through the sexual developmental process, the manner in which the conflicts implicit in this process were handled, and the libidinal content of his family relationships.

To effect a cure, he must facilitate the patient himself to become conscious of unresolved conflicts buried in the deep recesses of the unconscious mind, and to confront and engage with them directly.

In this sense, then, the object of psychoanalytic treatment may be said to be a form of self-understanding - once this is acquired, it is largely up to the patient, in consultation with the analyst, to determine how he shall handle this newly-acquired understanding of the unconscious forces which motivate him. One possibility, mentioned above, is the channelling of the sexual energy into the achievement of social, artistic or scientific goals - this is sublimation, which Freud saw as the motivating force behind most great cultural achievements.

Another would be the conscious, rational control of the formerly repressed drives - this is suppression. Yet another would be the decision that it is the super-ego, and the social constraints which inform it, which are at fault, in which case the patient may decide in the end to satisfy the instinctual drives. But in all cases the cure is effected essentially by a kind of catharsis or purgation - a release of the pent-up psychic energy, the constriction of which was the basic cause of the neurotic illness.

It should be evident from the foregoing why psychoanalysis in general, and Freud in particular, have exerted such a strong influence upon the popular imagination in the Western World over the past 90 years or so, and why both the theory and practice of psychoanalysis should remain the object of a great deal of controversy. In fact, the controversy which exists in relation to Freud is more heated and multi-faceted than that relating to virtually any other recent thinker (a possible exception being Darwin), with criticisms ranging from the contention that Freud's theory was generated by logical confusions arising out of his alleged long-standing addiction to cocaine (Cf. Thornton, E.M. Freud and Cocaine: The Freudian Fallacy) to the view that he made an important, but grim, empirical discovery, which he knowingly suppressed in favor of the theory of the unconscious, knowing that the latter would be more acceptable socially (Cf. Masson, J. The Assault on Truth).

It should be emphasized here that Freud's genius is not (generally) in doubt, but the precise nature of his achievement is still the source of much debate. The supporters and followers of Freud (and Jung and Adler) are noted for the zeal and enthusiasm with which they espouse the doctrines of the master, to the point where many of the detractors of the movement see it as a kind of secular religion, requiring as it does an initiation process in which the aspiring psychoanalyst must himself first be analyzed. In this way, it is often alleged, the unquestioning acceptance of a set of ideological principles becomes a necessary precondition for acceptance into the movement - as with most religious groupings. In reply, the exponents and supporters of psychoanalysis frequently analyze the motivations of their critics in terms of the very theory which those critics reject. And so the debate goes on.

Here we will confine ourselves to: (a) the evaluation of Freud's claim that his theory is a scientific one, (b) the question of the theory's coherence, (c) the dispute concerning what, if anything, Freud really discovered, and (d) the question of the efficacy of psychoanalysis as a treatment for neurotic illnesses.

This is a crucially important issue, since Freud not alone saw himself first and foremost as a pioneering scientist, but repeatedly asserted that the significance of psychoanalysis is that it is a new science, incorporating a new scientific method of dealing with the mind and with mental illness. And there can be no doubt but that this has been the chief attraction of the theory for most of its advocates since then - on the face of it, it has the appearance of being, not just a scientific theory, but an enormously strong scientific theory, with the capacity to accommodate, and explain, every possible form of human behavior.

However, it is precisely this latter which, for many commentators, undermines its claim to scientific status. On the question of what makes a theory a genuinely scientific one, Karl Popper's criterion of demarcation, as it is called, has now gained very general acceptance: viz. that every genuine scientific theory must be testable, and therefore falsifiable, at least in principle - in other words, if a theory is incompatible with possible observations it is scientific; conversely, a theory which is compatible with all possible observations is unscientific (Cf. Popper, K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery).

Thus the principle of the conservation of energy, which influenced Freud so greatly, is a scientific one, because it is falsifiable - the discovery of a physical system in which the total amount of energy was not constant would conclusively show it to be false. And it is argued that nothing of the kind is possible with respect to Freud's theory - if, in relation to it, the question is asked: 'What does this theory imply which, if false, would show the whole theory to be false?', the answer is 'nothing', the theory is compatible with every possible state of affairs - it cannot be falsified by anything, since it purports to explain everything. Hence it is concluded that the theory is not scientific, and while this does not, as some critics claim, rob it of all value, it certainly diminishes its intellectual status, as that was and is projected by its strongest advocates, including Freud himself.

A related (but perhaps more serious) point is that the coherence of the theory is, at the very least, questionable. What is attractive about the theory, even to the layman, is that it seems to offer us long sought-after, and much needed, causal explanations for conditions which have been a source of a great deal of human misery. The thesis that neuroses are caused by unconscious conflicts buried deep in the unconscious mind in the form of repressed libidinal energy would appear to offer us, at last, an insight in the causal mechanism underlying these abnormal psychological conditions as they are expressed in human behavior, and further show us how they are related to the psychology of the 'normal' person. However, even this is questionable, and is a matter of much dispute.

In general, when it is said that an event X causes another event Y to happen, both X and Y are, and must be, independently identifiable. It is true that this is not always a simple process, as in science causes are sometimes unobservable (sub-atomic particles, radio and electromagnetic waves, molecular structures, etc.), but in these latter cases there are clear 'correspondence rules' connecting the unobservable causes with observable phenomena.

The difficulty with Freud's theory is that it offers us entities (repressed unconscious conflicts, for example) which are said to be the unobservable causes of certain forms of behavior, but there are no correspondence rules for these alleged causes - they cannot be identified except by reference to the behavior which they are said to cause (i.e. the analyst does not demonstratively assert: 'This is the unconscious cause, and that is its behavioral effect'; he asserts: 'This is the behavior, therefore its unconscious cause must exist'). And this does raise serious doubts as to whether Freud's theory offers us genuine causal explanations at all.

At a less theoretical, but no less critical level, it has been alleged that Freud did make a genuine discovery, which he was initially prepared to reveal to the world, but the response which he encountered was so ferociously hostile that he masked his findings, and offered his theory of the unconscious in its place (Cf. Masson, J. The Assault on Truth). What he discovered, it has been suggested, was the extreme prevalence of child sexual abuse, particularly of young girls (the vast majority of hysterics are women), even in respectable nineteenth century Vienna. He did in fact offer an early 'seduction theory' of neuroses, which met with fierce animosity, and which he quickly withdrew, and replaced with theory of the unconscious. As one contemporary Freudian commentator explains it, Freud's change of mind on this issue came about as follows:

In this way, it is suggested, the theory of the Oedipus complex was generated.

This statement begs a number of questions, not least, what does the expression 'extraordinarily often' mean in this context? By what standard is this being judged? The answer can only be: by the standard of what we generally believe - or would like to believe - to be the case. But the contention of some of Freud's critics here is that his patients were not recalling childhood fantasies, but traumatic events in their childhood which were all too real, and that he had stumbled upon, and knowingly suppressed, the fact that the level of child sexual abuse in society is much higher than is generally believed or acknowledged. If this contention is true - and it must at least be contemplated seriously - then this is undoubtedly the most serious criticism that Freud and his followers have to face.

Further, this particular point has taken on an added, and even more controversial significance in recent years with the willingness of some contemporary Freudians to combine the theory of repression with an acceptance of the wide-spread social prevalence of child sexual abuse. The result has been that, in the United States and Britain in particular, many thousands of people have emerged from analysis with 'recovered memories' of alleged childhood sexual abuse by their parents, memories which, it is suggested, were hitherto repressed.

On this basis, parents have been accused and repudiated, and whole families divided or destroyed. Unsurprisingly, this in turn has given rise to a systematic backlash, in which organizations of accused parents, seeing themselves as the true victims of what they term 'False Memory Syndrome', have denounced all such memory-claims as 'falsidical', the direct product of a belief in what they see as the myth of repression. (Cf. Pendergast, M. Victims of Memory). In this way, the concept of repression, which Freud himself termed 'the foundation stone upon which the structure of psychoanalysis rests', has come in for more widespread critical scrutiny than ever before.

Here, the fact that, unlike some of his contemporary followers, Freud did not himself ever countenance the extension of the concept of repression to cover actual child sexual abuse, and the fact that we are not necessarily forced to choose between the views that all 'recovered memories' are either veridical or 'falsidical', are, perhaps understandably, frequently lost sight of in the extreme heat generated by this debate.

On this question, the situation is equally complex. For one thing, it does not follow that if Freud's theory is unscientific, or even false, that it cannot provide us with a basis for the beneficial treatment of neurotic illness, for the relationship between a theory's truth or falsity and its utility-value is far from being an isomorphic one. (The theory upon which the use of leeches to bleed patients in eighteenth century medicine was based was quite spurious, but patients did sometimes actually benefit from the treatment!). And of course even a true theory might be badly applied, leading to negative consequences.

One of the problems here is that is difficulty to specify what counts as a cure for a neurotic illness, as distinct, say, from a mere alleviation of the symptoms. In general, however, the efficiency of a given method of treatment is usually clinically measured by means of a 'control group' - the proportion of patients suffering from a given disorder who are cured by treatment X is measured by comparison with those cured by other treatments, or by no treatment at all.

Such clinical tests as have been conducted indicate that the proportion of patients who have benefited from psychoanalytic treatment does not diverge significantly from the proportion who recover spontaneously or as a result of other forms of intervention in the control groups used. So the question of the therapeutic effectiveness of psychoanalysis remains an open and controversial one.

Freud's theories and research methods have always been controversial. He and psychoanalysis have been criticized in very extreme terms. For an often-quoted example, Peter Medawar, a Nobel Prize winning immunologist, said in 1975 that psychoanalysis is the "most stupendous intellectual confidence trick of the twentieth century".[47] However, Freud has had a tremendous impact on psychotherapy. Many psychotherapists follow Freud's approach to an extent, even if they reject his theories.

One influential post-Freudian psychotherapy has been the primal therapy of the American psychologist Arthur Janov.

Freud's contributions to psychotherapy have been extensively criticized and defended by many scholars and historians.

Critics include H. J. Eysenck, who wrote that Freud 'set psychiatry back one hundred years', consistently mis-diagnosed his patients, fraudulently misrepresented case histories and that "what is true in Freud is not new and what is new in Freud is not true".

Betty Friedan also criticized Freud and his Victorian slant on women in her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. Freud's concept of penis envy - and his definition of female as a negative - was attacked by Kate Millett, whose 1970 book Sexual Politics explained confusion and oversights in his work. Naomi Weisstein wrote that Freud and his followers erroneously thought that his "years of intensive clinical experience" added up to scientific rigor.

Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen wrote in a review of Han Isra‘ls's book Der Fall Freud published in The London Review of Books that, "The truth is that Freud knew from the very start that Fleischl, Anna O. and his 18 patients were not cured, and yet he did not hesitate to build grand theories on these non-existent foundations...he disguised fragments of his self-analysis as ÔobjectiveŐ cases, that he concealed his sources, that he conveniently antedated some of his analyses, that he sometimes attributed to his patients Ôfree associationsŐ that he himself made up, that he inflated his therapeutic successes, that he slandered his opponents."

Jacques Lacan saw attempts to locate pathology in, and then to cure, the individual as more characteristic of American ego psychology than of proper psychoanalysis. For Lacan, psychoanalysis involved "self-discovery" and even social criticism, and it succeeded insofar as it provided emancipatory self-awareness.

David Stafford-Clark summed up criticism of Freud: "Psychoanalysis was and will always be Freud's original creation. Its discovery, exploration, investigation, and constant revision formed his life's work. It is manifest injustice, as well as wantonly insulting, to commend psychoanalysis, still less to invoke it 'without too much of Freud'." It's like supporting the theory of evolution 'without too much of Darwin'. If psychoanalysis is to be treated seriously at all, one must take into account, both seriously and with equal objectivity, the original theories of Sigmund Freud.

Ethan Watters and Richard Ofshe wrote, "The story of Freud and the creation of psychodynamic therapy, as told by its adherents, is a self-serving myth".

Freud did not consider himself a philosopher, although he greatly admired Franz Brentano, known for his theory of perception, as well as Theodor Lipps, who was one of the main supporters of the ideas of the unconscious and empathy.

In his 1932 lecture on psychoanalysis as "a philosophy of life" Freud commented on the distinction between science and philosophy:

Freud's model of the mind is often considered a challenge to the enlightenment model of rational agency, which was a key element of much modern philosophy. Freud's theories have had a tremendous effect on the Frankfurt school and critical theory. Following the "return to Freud" of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, Freud had an incisive influence on some French philosophers.

Freud once openly admitted to avoiding the work of Nietzsche, "whose guesses and intuitions often agree in the most astonishing way with the laborious findings of psychoanalysis". Nietzsche, however, vociferously rejected the conjecture of 'scientific' men, and despite also 'diagnosing' the death of a God, chose instead to embrace the animal desires (or 'Dionysian energies') the humanist Freud sought to reject through positivism.

Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper argued that Freud's psychoanalytic theories were presented in untestable form. Psychology departments in American universities today are scientifically oriented, and Freudian theory has been marginalized, being regarded instead as a "desiccated and dead" historical artifact, according to a recent APA study.

Recently, however, researchers in the emerging field of neuro-psychoanalysis have argued for Freud's theories, pointing out brain structures relating to Freudian concepts such as libido, drives, the unconscious, and repression. Founded by South African neuroscientist Mark Solms, neuro-psychoanalysis has received contributions from researchers including Oliver Sacks, Jaak Panksepp, Douglas Watt, Ant—nio Damasio, Eric Kandel, and Joseph E. LeDoux. Still other clinical researchers have recently found empirical support for more specific hypotheses of Freud such as that of the "repetition compulsion" in relation to psychological trauma.

The idea of Akhenaten as the pioneer of a monotheistic religion that later became Judaism was promoted by Sigmund Freud in his book Moses and Monotheism and thereby entered popular consciousness. Freud argued that Moses had been an Atenist priest forced to leave Egypt with his followers after Akhenaten's death. Freud argued that Akhenaten was striving to promote monotheism, something that the biblical Moses was able to achieve. Following his book, the concept entered popular consciousness and serious research.

With a belief in monotheism, several researchers believe Sigmund Freud was also Moses, Akhenaten and Zoroaster. That cannot be proven.